Abstract

Background

Blastocystis sp. is one of the most prevalent parasites found in human stool and has been recently considered an opportunistic emerging pathogen in immunocompromised individuals. However, cases of invasive intestinal infections and skin rashes have been attributed to infection by Blastocystis sp in immunocompetent individuals, suggesting that it is an emerging parasite with pathogenic potential.

Findings

We present a case of a 22 year old female patient who complained of pain in the left hypochondrium. Ultrasonography and abdominal computed tomography scans showed two splenic cysts. The cyst fluid analysis demonstrated numerous Blastocystis sp.; PCR and DNA sequencing analyses confirmed the presence of Blastocystis subtype 3.

Conclusions

This is, to our knowledge, the first case report of the presence of Blastocystis subtype 3 in extra-intestinal organs and is strong evidence that Blastocystis sp. is potentially pathogenic and invasive. However, further studies are required to determine the pathogenicity of the parasite.

Keywords: Blastocystis spp, Immunocompetent individual, Pathogenicity, Splenic cyst

Findings

Blastocystis spp. are parasites of the intestinal tract found in many hosts including humans [1]. This pathogen is commonly found in apparently healthy and asymptomatic individuals and in patients with gastrointestinal disease. Its pathogenicity has been reported in the literature in immunocompromised pediatric, cancer, and HIV-infected patients [2-5], however, the clinical relevance of Blastocystis sp. in immunocompetent individuals remains unclear. The association between Blastocystis sp. and arthritis, dermatological disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome [6-8] have also been reported. In addition, its invasive potential has been suggested in animal models [9,10] and in humans [11-13]. Recently, cases of enteroinvasion by Blastocystis sp were shown in vivo through endoscopy and biopsy analyses [13]. In this case report, Blastocystis sp. was detected in ulcers in the cecum, transverse colon, and rectum of an immunocompetent patient.

Blastocystis has been traditionally named Blastocystis hominis when isolated from human fecal materials. However, recent phylogenetic analyses suggest limiting its name to “Blastocystis species” because of their genetic diversity. This parasite has been considered as a species complex comprising 13 subtypes, of which at least nine have been found in humans [14]. Furthermore, they exhibit wide genetic diversity that is sufficient to assign them to different species [15]. The confirmation of their species status and determination of virulence and pathogenic profiles might explain why some patients are asymptomatic while others present clinical symptoms [16].

Blastocystis spp. was discovered over a century ago, however, many issues regarding its infection still remain unanswered. Accumulating evidence reinforces the pathogenic potential of Blastocystis sp. in immunocompetent individuals [6-8]; however, systematic studies characterizing different clinical isolates of Blastocystis subtypes and new diagnostic approaches are needed to improve our understanding about these cases. This is the first case report describing the presence of Blastocystis sp. in the fluid of splenic cysts. According to our observation, the following question is raised: ‘Can Blastocystis be the culprit for the formation of splenic cysts or is this association based on other reasons?’

Case presentation

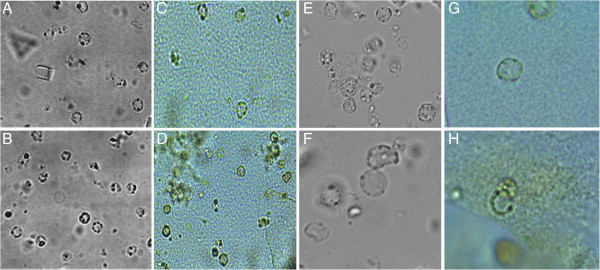

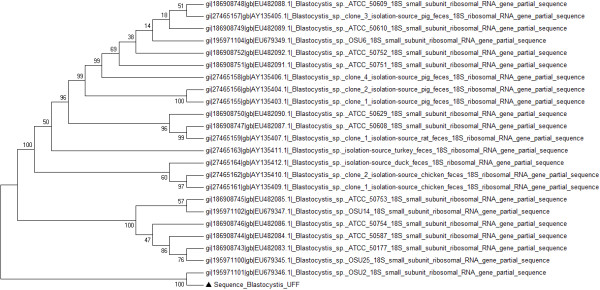

A 22 year-old white female, residing in Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, sought treatment in 2009 reporting localized pain in the left hypochondrium. The ultrasonography showed a 15.1 × 11.1 cm cyst in the spleen. In 2012, this patient returned for medical attention due to an intensification of the pain that affected her walking. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of two spleen cysts (11 × 11 cm) with peripheral calcifications (one intra- and one extra-splenic). The hematological and biochemical tests showed results within normal limits and the chest x-ray was normal, however, the urine culture was positive for Streptococcus agalactiae. Surgical treatment was recommended and, one month prior to operation, the patient received the pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae and meningococcal vaccines. A laparoscopic excision of the splenic cyst was performed and the postoperative recovery was uneventful; the patient was discharged on the second post-operative day. The cytological examination of cyst fluid showed the presence of histiocytes, lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and lysed erythrocytes. No evidence of cancerous cells was observed and the biochemistry results were as follows: 3.6 g/dl albumin, 3 mg/dl glucose, 137 mEq/L sodium chloride, 3.9 Eq/L potassium chloride, 1132 U/L lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 76 U/L amylase, and 65 U/L lypase. Furthermore, the presence of crystals and Blastocystis sp. were observed in the microscopic examinations of the fluid contained in the cyst (Figure 1). The presence of Blastocystis sp. was further confirmed by PCR using primers and conditions previously described [17] and subsequent sequencing. The obtained small subunit ribosomal DNA nucleotide partial sequence was compared to other sequences available in this database using the BLASTN program from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). This analysis showed 99% similarity between our sequence and the Blastocystis sp. OSU2 sequence (GenBank: EU679346) characterized as Blastocystis subtype 3. The phylogenetic analysis showed that sequence of this study clustered with Blastocystis sp OSU2 sequence (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Light microscope images of Blastocystis sp. in splenic fluid specimens. A and B (unstained wet slides), C and D (iodine stained wet slides), 40× magnification. E and F (unstained wet slides), G and H (iodine stained wet slides), 100× magnification.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of partial SSU rRNA sequences of Blastocystis isolates. Neighbor-Joining tree displaying the relationships of Blastocystis isolates, inferred by analysis of partial SSU rDNA sequence data using Kimura’s 2 parameter distance estimates. The number at each branch point represents the percentage of bootstrap support calculated from 1,000 trees. The sequences used for comparison were from Genbank. The triangle indicates isolates from this study.

Discussion

Splenic cysts constitute very rare clinical entities. They may occur secondary to trauma or parasitic infestations, particularly by Echinococcus granulosus[18,19]. Cases of isolated splenic involvement in hydatid disease are not very frequent even in endemic regions [18]. Interestingly, this report describes the presence of Blastocystis subtype 3 in splenic cysts, a parasite mostly found in human stool. A previous case study described Blastocystis present in the liver abscess aspirate of a patient with history of fever, watery diarrhea and high Anti-Entamoeba histolytica antibody titer [11]. Although the pathogenic mechanisms are unclear; we speculate that two hypotheses could be considered to explain how the Blastocystis sp got into the spleen. First, Blastocystis sp might penetrate and invade the intestinal mucosa and submucosa causing ulcers, and progress through the blood and/or lymphatic system and migrate to the spleen. Second, the parasite might gain access to extra-intestinal sites with the help of coinfections or other pathological circumstances. To complement these hypotheses, Blastocystis sp have to survive during infection, essentially by responding rapidly to changes in the microenvironment in intestine, blood and escaping host defense mechanisms. There are few studies addressing the mechanism of pathogenesis, regarding cellular microbiology, immune evasion, and life cycle of Blastocystis sp. This parasite one of the most difficult organisms to identify in stool samples because of their morphological biodiversity; some of the commonly reported forms in culture or in fecal specimens are vacuolar, granular or amoeboid. However, other forms that might occur with relative frequency might be missed by untrained examiners [1]. Conversely, the lack of standardized diagnosis may also lead to misinterpretation of results [1]. Recently, a study revealed poor agreement in reporting Blastocystis sp. positive specimens when comparing the diagnostic performance of various European reference laboratories [20]. Several molecular epidemiological studies suggest a possible correlation between subtypes and clinical presentations of Blastocystis infections. Other studies observed no association between presence of this organism and disease [21,22]. These discrepant results might be explained by subtypes with differences in virulence, or by low sensitivity in the diagnosis techniques used. This scenario is strikingly similar to that of an erroneous diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica. For many years, the virulence and pathogenicity of E. histolytica was questioned until molecular techniques irrefutably showed that there are two genetically distinct, but morphologically identical, species in what was formerly known as E. histolytica. Differences in the pathogenesis of E. histolytica and E. dispar also helped explain the epidemiology, presentation of symptoms, and pathology of amoebiasis [23].

Currently, there is not enough evidence showing that Blastocystis sp. is a nonpathogenic organism and its association with gastrointestinal diseases raises questions about its pathogenicity [5-8]. Moreover, there are accumulating data suggesting its pathogenic potential in immunocompetent individuals [1,12-14].

The genome of Blastocystis subtype 7 encodes proteases, hexose digestion enzymes, lectins, protease inhibitors, and glycosyltransferases besides several proteins that are predicted to be secreted [24]. The roles of some of these proteins are known in other parasites [25] with direct connections to their pathogenicity in processes such as host cell invasion, excystation, metabolism, cytoadherence, and other virulence functions [24]. Thus, proteomics and transcriptomic analyses will be useful in order to show whether these predicted proteins have any role in the pathogenesis of Blastocystis.

Protease activity has been described in Blastocystis spp. isolated from symptomatic patients [26-28]. In addition, other studies have demonstrated that cysteine proteases from Blastocystis can increase epithelial permeability by modulating the tight junction complex [29], induce pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) [30], and degrade human immunoglobulin A (IgA) [31]. Cysteine proteases are important enzymes for host invasion and infection and are well recognized as virulence factors in pathogenic protozoa [25].

In this study, Blastocystis subtype 3 was detected in splenic cysts. The literature on the molecular analysis of human Blastocystis isolates suggests that they are mostly of genotype subtype 3. Genotype variability has been reported to play an influential role in the pathogenicity of Blastocystis[32,33]. However, previous studies have associated subtypes 1, 4, and 7 with human pathology, whereas subtypes 2 and 3 predominate among healthy carriers [12]. Infections with mixed subtypes, and the high degree of genetic diversity among subtypes, obscure possible correlations between pathogenicity and Blastocystis subtypes [5,34,35].

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report describing Blastocystis subtype 3 in an extra-intestinal organ. We have no knowledge as to how the parasite gained access to the spleen. The answer to this question will deepen our understanding about the pathogenicity of Blastocystis sp. Its pathogenic potential is a relevant threat to immunocompetent individuals and this report emphasizes the importance of an increased awareness and recognition of this pathogen.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HLCS, FCS and HWM conceived and designed the study. FCS carried out the microscopy examination. HLCS carried out the molecular approaches, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. HWM supervised the study, carried out the laboratory work, intellectual interpretation and critical. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Helena Lúcia Carneiro Santos, Email: helenalucias@ioc.fiocruz.br.

Fernando Campos Sodré, Email: fcsodre1952@gmail.com.

Heloisa Werneck de Macedo, Email: hwmacedo@terra.com.br.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by PAPES-VI/FIOCRUZ. The funders had no participation in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Scanlan PD. Blastocystis: past pitfalls and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noureldin MS, Shaltout AA, El Hamshary EM, Ali ME. Opportunistic intestinal protozoa linfections in immunocompromised children. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1999;29:951–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasova Y, Sahin B, Koltas S, Paydas S. Clinical significance and frequency of Blastocystis hominisin Turkish patients with hematological malignancy. Acta Med Okayama. 2000;54:133–136. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan A, Karyadi T, Dwintasari SW, Sari IP, Yunihastuti E, Djauzi S, Smith HV. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients presenting with diarrhoea in Jakarta, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza H, Tan KSW. Clinical aspects of Blastocystis infections: advancements amidst controversies. Parasitology Res Monog. 2012;4:65–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32738-4_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Greco V. Cutaneous lesions in Blastocystis hominis infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:322–332. doi: 10.1080/00015550410025949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Delfanian K. Blastocystis hominis associated acute urticaria. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346:80–81. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182801478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier P, Wawrzyniak I, Vivarès CP, Delbac F, El Alaoui H. New insights into Blastocystis spp.: a potential link with irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein EM, Hussein AM, Eida MM, Atwa MM. Pathophysiological variability of different genotypes of human Blastocystis hominis Egyptian isolates in experimentally infected rats. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0833-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwakil HS, Hewedi IH. Pathogenic potential of Blastocystishominis in laboratory mice. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:685–689. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1922-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu KC, Lin CC, Wang TE, Liu CY, Chen MJ, Chang WH. Amoebic liver abscess or is it? Gut. 2008;57:683. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.119149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patino WD, Cavuoti D, Banerjee SK, Swartz K, Ashfaq R, Gokaslan T. Cytologic diagnosis of Blastocystis hominis in peritoneal fluid: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:718–720. doi: 10.1159/000325628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janarthanan S, Khoury N, Antak F. An unusual case of invasive Blastocystishominis infection. Endoscopy. 2011;43:E185–E186. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KS, Mirza H, Teo JD, Wu B, Macary PA. Current views on the clinical relevance of Blastocystis spp. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:28–35. doi: 10.1007/s11908-009-0073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkar U, Traub RJ, Vitali S, Elliot A, Levecke B, Robertson I, Geurden T, Steele J, Drake J, Thompson RC. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis isolates from zooanimals and their animal-keepers. Vet Parasitol. 2010;19:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parija SC, Jeremiah SS. Blastocystis: taxonomy, biology and virulence. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:7–25. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold CR, Arendrup MC, Jespersgaard C, Molbak K, Nielsen HV. Detecting Blastocystis using parasitologic and DNA-based methods: a comparative study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adas G, Oguzhan KO, Altiok M, Battal M, Bender O, Ozcan D, Karahan S. Diagnostic problems with parasitic and non-parasitic splenic cysts. BMC Surg. 2009;9:9–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukar MM, Pukar SM. Giant solitary hydatid cyst of spleen–a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:435–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzinger J, Botero-Kleiven S, Castelli F, Chiodini PL, Edwards H, Köhler N, Gulletta M, Lebbad M, Manser M, Matthys B, N’Goran EK, Tannich E, Vounatsou P, Marti H. Microscopic diagnosis of sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin-fixed stool samples for helminths and intestinal protozoa: a comparison among European reference laboratories. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leder K, Hellard ME, Sinclair MI, Fairley CK, Wolfe R. No correlation between clinical symptoms and Blastocystis hominis in immunocompetent individuals. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1390–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HY, Chiang DH, Wang CC, Chen TL, Fung CP, Lin CP, Cho WL, Liu CY. Clinical significance of Blastocystis hominis: experience from a medical center in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008;41:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoeud F, Roussel M, Noel B, Wawrzyniak I, Da Silva C, Diogon M, Viscogliosi E, Brochier-Armanet C, Couloux A, Poulain J, Segurens B, Anthouard V, Texier C, Blot N, Poirier P, Ng GC, Tan KS, Artiguenave F, Jaillon O, Aury JM, Delbac F, Wincker P, Vivarès CP, El Alaoui H. Genome sequence of the stramenopile Blastocystis, a human anaerobic parasite. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalan PD, Stensvols CR. Blastocystis: getting to grips with our guileful guest. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza H, Tan KS. Blastocystis exhibits inter- and intra-subtype variation in cysteine protease activity. Parasitol Res. 2009;104:355–361. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramathi S, Suresh K, Anita ZB, Kuppusamy UR. Infections of Blastocystis hominis and microsporidia in cancer patients: are they opportunistic? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:267–269. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamanikam A, Govind SK. Amoebic forms of Blastocystis spp.–evidence for a pathogenic role. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:295–304. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza H, Wu Z, Teo JD, Tan KS. Statin-pleiotropy prevents rho kinase-mediated intestinal epithelial barrier compromise induced by Blastocystis cysteine proteases. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1474–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthia MK, Lu J, Tan KS. Blastocystis ratti contains cysteine proteases that mediate interleukin-8 response from human intestinal epithelial cells in an NF-kB-dependent manner. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:435–443. doi: 10.1128/EC.00371-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthia MK, Vaithilingam A, Lu J, Tan KS. Degradation of human secretory immunoglobulin A by Blastocystis. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:386–389. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souppart L, Sanciu G, Cian A, Wawrzyniak I, Delbac F, Capron M, Dei-Cas E, Boorom K, Delhaes L, Viscogliosi E. Molecular epidemiology of human Blastocystis isolates in France. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:413–421. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasamy V, Roslani AC, Rani KU, Govind SK. Advantage of using colonic washouts for Blastocystis detection in colorectal cancer patients. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:162–166. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogruman-Al F, Dagci H, Yoshikawa H, Kurt O, Demirel M. A possible link between subtype 2 and asymptomatic infections of Blastocystis hominis. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:685–689. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TD, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Subtype distribution of Blastocystis isolates identified in a Sydney population and pathogenic potential of Blastocystis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1746-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]