Abstract

Dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain project to the caudate/putamen and nucleus accumbens, respectively, establishing the mesostriatal and the mesolimbic pathways. However, the mechanisms underlying the development of these pathways are not well understood. In the current study, the EphA5 receptor and its corresponding ligand, ephrin-A5, were shown to regulate dopaminergic axon out-growth and influence the formation of the midbrain dopaminergic pathways. Using a strain of mutant mice in which the EphA5 cytoplasmic domain was replaced with β-galactosidase, EphA5 protein expression was detected in both the ventral tegmental area and the substantia nigra of the midbrain. Ephrin-A5 was found in both the dorsolateral and the ventromedial regions of the striatum, suggesting a role in mediating dopaminergic axon-target interactions. In the presence of ephrin-A5, dopaminergic neurons extended longer neurites in in vitro coculture assays. Furthermore, in mice lacking ephrin-A5, retrograde tracing studies revealed that fewer neurons sent axons to the striatum. These observations indicate that the interactions between ephrin-A ligands and EphA receptors promote growth and targeting of the midbrain dopaminergic axons to the striatum.

Keywords: axon pathfinding, receptor tyrosine kinase, substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, nigrostriatal, striatum

INTRODUCTION

During development, axon guidance cues direct growing axons to their appropriate targets and aid in the establishment of proper connections. Axon termination within the target is often accomplished with contact mediated guidance molecules such as the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligands. Members of the Eph family regulate diverse cellular functions such as angiogenesis, cell migration, and synaptic plasticity, in addition to axon guidance (van der Geer et al., 1994; Flanagan and Vanderhaeghen, 1998; Zhou, 1998; Wilkinson, 2001; Kullander and Klein, 2002; O’Leary and McLaughlin, 2005; Pasquale, 2008). The Eph family comprised 14 receptors divided into two subgroups, A and B. The ligands of the Eph receptors, the ephrins, are also divided into two subgroups, A and B, which bind preferentially to receptors within their own subgroup (Gale et al., 1996). Although both ephrin subgroups are membrane bound, ephrin-B ligands have a transmembrane domain, whereas the ephrin-A ligands are bound to the membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage. Curiously, both types of ligands are capable of reverse signaling, making bidirectional communication between interacting neurons possible (Davy and Soriano, 2005; Holmberg et al., 2005; Konstantinova et al., 2007; Lim et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008).

The initial finding that the Eph receptors played a role in axon guidance rested on evidence that gradients of the Eph receptor ligands, ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A5, were found in the tectum, the target site of axons originating from the retina (Cheng et al., 1995; Drescher et al., 1995). In addition, these molecules selectively repelled temporal retinal ganglion axons but not nasal axons. Since then, the Eph family of receptors has been implicated in the proper formation of several axon pathways, including hippocamposeptal, thalamocortical, and geniculocortical projections, as well as retinal axon crossing in the optic chiasm (Gao et al., 1996, 1998, 1999; Marcus et al., 2000; Mann et al., 2002; Yue et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2003; Cang et al., 2005, 2008).

Multiple axon guidance molecules, including the ephrins, are likely to participate in the wiring of the dopaminergic pathways. In the mouse, midbrain dopaminergic neurons are born around embryonic day (E)9 at the midbrain–hindbrain boundary (Bayer et al., 1995) and begin to migrate to the ventral midbrain where they develop into three main nuclear groups referred to as the retrorubral field (A8), the substantia nigra (SN) (A9), and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (A10) (Dahlstom and Fuxe, 1964). At E11, short neurites begin to extend dorsally, away from the midline and turn sharply to extend rostrally toward the ganglionic eminence between E12 and E13 (Nakamura et al., 2000; Gates et al., 2004). Manipulation of ventral midbrain neurite extension using grafts from the dorsal midbrain, the medial ganglionic eminence, and the striatum suggest that the directed growth of dopaminergic axons is due to chemotactic guidance (Gates et al., 2004; Hernandez-Montiel et al., 2008). Within the striatal target, the initial axon contacts from the midbrain are widespread with no distinct regionalization (Hu et al., 2004). Mislocated collaterals are believed to be pruned in the later stages of development. By E17 in the mouse, fibers extending from the midbrain have partially segregated into two bundles to become the mesostriatal and mesolimbic tract separating the connections to the limbic system from the motor functions of the dorsolateral striatum. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of the ascending dopaminergic pathways are still being identified.

EphA5 plays a key role in development, and its expression is robust in many limbic structures, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus (Gao et al., 1999; Yue et al., 2002), whose functions are modulated in part by dopaminergic projections (Spanagel and Weiss, 1999; Salamone and Correa, 2002). Furthermore, loss of EphA5 function has been shown to decrease striatal dopamine levels and modulate susceptibility to drug addiction (Halladay et al., 2004; Seiber et al., 2004). However, the mechanism by which EphA5 and its ligands regulate the dopaminergic pathways remains unclear. In this report, we demonstrate that EphA5 and ephrin-A5 interact to promote axon termination of the midbrain dopaminergic neurons in the striatum. These observations suggest that the Eph ligand-receptor system modulate axon-target interactions in the developing dopaminergic system.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animals

Mouse lines and rats were housed and cared for in strict accordance to the guidelines set by the Laboratory for Animal Services at Rutgers University. All rodents were maintained under standard conditions. Timed-pregnant rats were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). The rats were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and embryonic day (E)14 embryos were collected via caesarean section.

Timed-pregnant mice bred to generate embryos for tissue culture and expression studies were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and embryos were removed via caesarean section. The day of the vaginal plug was considered as E0. Adult mice used for histology were anesthetized with 2 µL/g of ketamine HCl (80 mg/mL)/xylazine HCl (12 mg/mL) solution (Sigma K113, St. Louis, MO) and then perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS (pH 7.4). Ephrin-A5−/− mice used in tracing studies were a gift from J. Frisen. PCR genotyping of these mice is as previously described (Frisen et al., 1998). TH-GFP transgenic mice used in the striatal slice overlay assay were generated previously (Matsushita et al., 2002). In these mice, green fluorescent protein (GFP) was expressed under the control of a tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene promoter, thus enabling dopaminergic neurons to be marked. Kinase-inactive EphA5LacZ/LacZ mice were generated by replacement of the intracellular domain of the EphA5 receptor with β-galactosidase (Feldheim et al., 2004). Polymerase chain reaction was used to genotype the mutant and transgenic mice.

Tissue Culture

Cocultures of the Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons with NIH3T3 Cells With and Without Ephrin-A5 Expression

NIH 3T3 cell lines expressing ephrin-A5 were developed previously (Gao et al., 1999). For coculture experiments either ephrin-A5 expressing or control NIH 3T3 cells were plated on six-well dishes and allowed to grow to 90% confluency. To examine the effect of ephrin-A5 on dopaminergic neurons, dissociated cultures of the ventral midbrain from E14 rat embryos or from E12.5 EphA5LacZ/LacZ or wild-type mouse embryos were plated over ephrin-A5-expressing cell lines at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well (35 mm). The cultures were maintained for 72 h, or 48 h for mouse cultures, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% serum and antibiotics and then fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Dopaminergic neurons were identified from the mixed culture by immunocytochemistry with rabbit anti-TH antibody (1:100, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and Cy3 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

Culturing the Midbrain Neurons on a Substrate of Purified Ephrin-A5

To grow neurons over a substrate of ephrin-A5, six-well culture dishes were first coated with 0.1 mg/mL poly-d-lysine and incubated overnight at 37°C. After the plates were rinsed with 1× PBS and air dried, 100 µL of crosslinked ephrin-A5-Fc (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at concentrations of 10 µg/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 0.1 µg/mL or Human-Fc IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, Jackson, NY) at a concentration of 1 µg/mL were plated over the dish surface and air dried. Ephrin-A5-Fc was crosslinked with Human-Fc IgG in a 5 to 1 ratio in 1× PBS at 37°C for 2 h. Dissociated E14 rat midbrain neurons were plated in each well at a density of 1 × 106 cells and cultured for 48 h in DMEM. The cultures were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS and stained with anti-TH antibody as described in the previous section.

PI-PLC Treatment of Cocultures

To remove ephrin-A5 from the cell surface, 90% confluent plates containing either control or ephrin-A5 expressing NIH 3T3 cells were treated with 0.8 units (U)/mL of phosphatidylinositol-specific, phospholipase C (PI-PLC), (Sigma P5542, St. Louis, MO), 1 h prior to the addition of dissociated rat midbrain neurons. The cocultures were maintained for 48 h in the presence of PI-PLC, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and then stained for TH expression as described earlier.

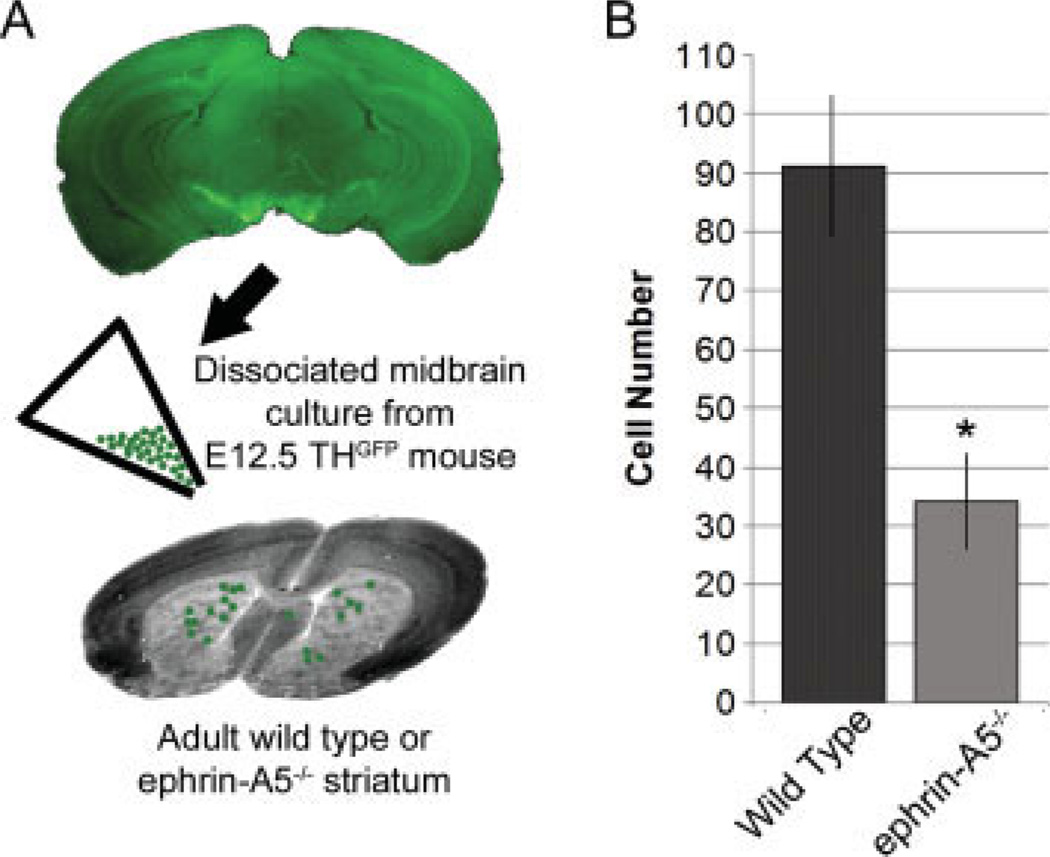

Striatal Slice Overlay Assay with Dopaminergic Neurons

Two-month-old wild type and ephrin-A5−/− mice were first euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. The brains were quickly removed from the skull and set in low melting point agarose in 1× complete HBSS (Polleux and Ghosh, 2002). Coronal striatal slices were made with a vibratome set to produce 100 µm slices. Slices were placed onto Millicell-CM organotypic cell culture inserts (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and incubated in slice culture medium (Polleux and Ghosh, 2002). E12.5 embryos were then removed from TH-GFP mice. After harvesting, embryos were screened under a fluorescent dissecting scope for GFP expression. Positive embryos were used to create a dissociated culture from the ventral midbrain and then plated over the slices (Polleux and Ghosh, 2002). Cultures were maintained at 37°C for 18 h. After incubation, wells were rinsed with 1× PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Membranes of the culture inserts with the striatal slices were then cut from the well and placed onto glass slides for imaging.

Histology

In Situ Hybridization

To analyze the ephrin-A5 expression in the rodent brain, in situ hybridization was performed on 14 µm coronal brain slices from E18 mice. P33-radiolabeled ephrin-A5 antisense and sense probes were generated and used according to methods previously described and published (Zhang et al., 1996).

β-Galactosidase Staining

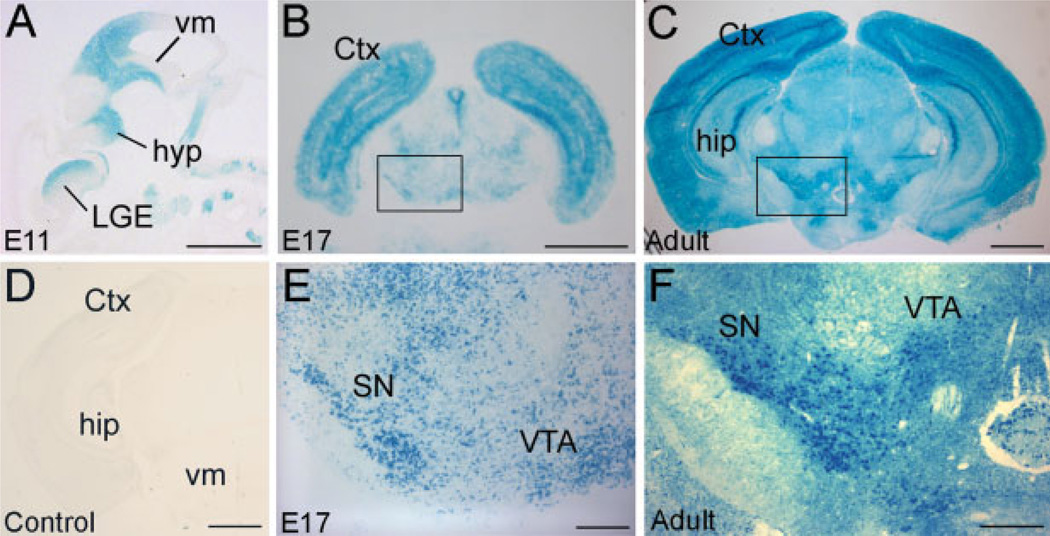

Adult and E17 EphA5LacZ/+ brains were dissected and quickly frozen in Tissue-tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Brains were then cryosectioned into 10 µm coronal sections and collected onto plus-charged glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Sections were quickly postfixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/0.5% glutaraldehyde solution in 1× PBS for 1 min prior to incubation in reaction buffer containing 1 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2 mM magnesium chloride, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.02% NP-40. E11 wholemount embryos were fixed for 15 min prior to being permeabilized in 0.02% NP-40 for 30 min before X-gal treatment. Tissue was allowed to develop for 18 h at 37°C. Wholemount embryos were paraffin embedded and sectioned into 10 µm sagittal sections. Wild-type tissue exhibited no response to X-gal treatment [Fig. 2(D)].

Figure 2.

EphA5 expression in the mouse midbrain. Heterozygous EphA5LacZ/+ mouse tissue was treated with substrates for β-galactosidase to yield an indigo precipitate. (A) An E11 sagittal section. EphA5 expression is apparent in the ventral midbrain and in the ganglionic eminence. (B,E) An E17 coronal section. EphA5 is evident in the substantia nigra. (C,F) An adult coronal section. Both the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental areas have receptor expression continuing into adulthood. (D) Wild-type adult control. No β-galactosidase enzymatic activity was observed. Higher magnifications of the boxed areas from (B,C) are shown in (E,F), respectively. Ctx, cortex; hyp, hypothalamus; hip, hippocampus; LGE, Lateral Ganglionic Eminence; SN, substantia nigra; vm, ventralmidbrain; VTA, ventral tegmental area. Scale bar = 1mm(A–D); 250 µm (E); 300 µm (F).

For cell cultures, E12.5 embryos were removed from heterozygous EphA5LacZ/+ animals and a dissociated culture was made from the ventral midbrain. Cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine coated six-well dishes, fixed, and treated with the X-gal reaction buffer followed by immunocytochemical staining with rabbit anti-TH antibody and Cy3 anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody as described earlier.

Retrograde Tracing

For intercranial injections of axon tracer, mice were first anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine solution. Using a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Il), an injection was placed with the following coordinates: 0.9–1.0 mm anterior, 1.8–1.9 mm lateral, and 2.75–3.00 mm ventral from the bregma. Seventy nanoliters of fluorogold (Fluorochrome, Denver, CO) was injected into the striatum of adult ephrin-A5−/−, EphA5LacZ/LacZ and wild-type mice. Injections were made with a 26-gauge Hamilton pressure injection syringe at a speed of 10 nL per minute for 7 min. After survival for 5 days, mice were perfused, and their brains were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Brains were later cryosectioned into 50 µm sections. All sections were collected, imaged, and analyzed for the number of total labeled cells.

Images were captured on an inverted Zeiss microscope using Axiovision software and on an inverted Nikon microscope using ImagePro Plus software. Image analyses, including cell counting and neurite length measurements were made with ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD).

RESULTS

Expression of EphA5 and Ephrin-A5 in the Developing Midbrain and Striatum

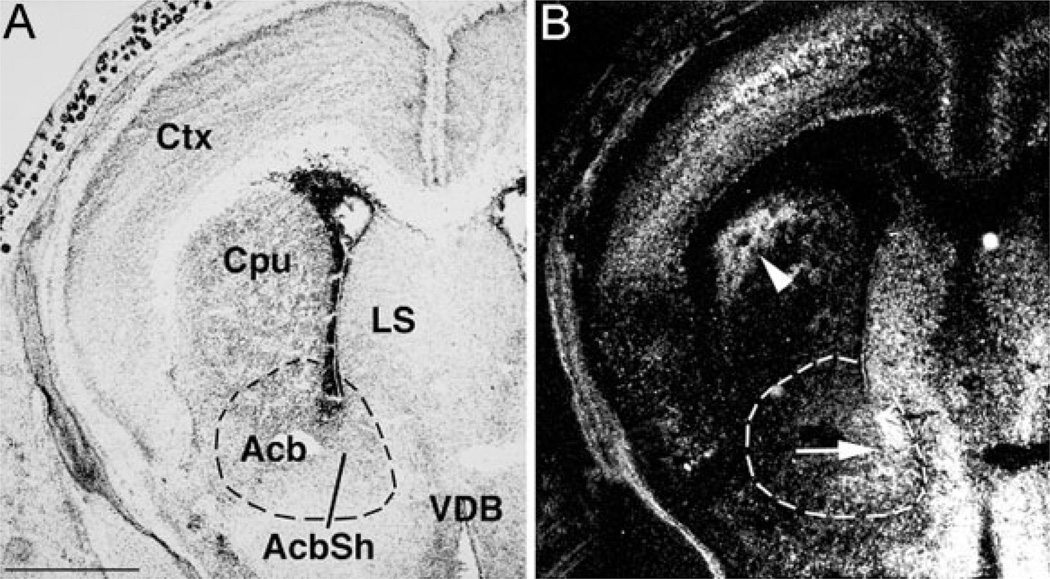

Expression studies of EphA5 and its ligand, ephrin-A5, revealed a potential role for these molecules in the development of the midbrain dopaminergic system. To observe the expression pattern of ephrin-A5, an in situ hybridization survey in mice with probes against ephrin-A5 mRNA was performed. Strong expression was found at E18 in both the dorsolateral and ventromedial striatum, in correspondence to the timing of striatal targeting by the ascending midbrain dopaminergic fiber tracts [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

In situ hybridization with ephrin-A5 antisense probe on E18 mouse brain coronal slices. (A) Anatomical features as revealed by Thionin staining. (B) Ephrin-A5 signals are evident in the dorsolateral caudate putamen (arrowhead) and nucleus accumbens shell (arrow). Acb(Sh), nucleus accumbens (shell); Cpu, caudate putamen; Ctx, neocortex; LS, lateral septum; VDB, vertical diagonal band. Scale bar = 1 mm.

The potential involvement of the EphA5 receptor in the development of the midbrain dopaminergic system was suggested from the results of an analysis to determine the expression of the receptors present in the midbrain (Yue et al., 1999). To further examine the potential role of EphA5, heterozygous EphA5LacZ/+ knock-in mice, in which the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor was replaced with β-galactosidase, were analyzed to identify expression of the receptor in the developing midbrain dopaminergic neurons. This analysis revealed that EphA5 protein was expressed in the ventral midbrain in both the substantia nigra and in the ventral tegmental area [Fig. 2 (B,C,E,F)]. Ventral midbrain expression was observed as early as E11 [Fig. 2(A)] and EphA5 continued to be expressed throughout development at moderate levels into adult stages [Fig. 2(C,F)]. Notably, islands of EphA5 expression in the striatum, called striatal patches (not shown), can also be seen in the caudate/putamen around postnatal day (P)0, corresponding to the timing of synaptic strengthening by the midbrain fibers having reached their target (Antonopoulos et al., 2002).

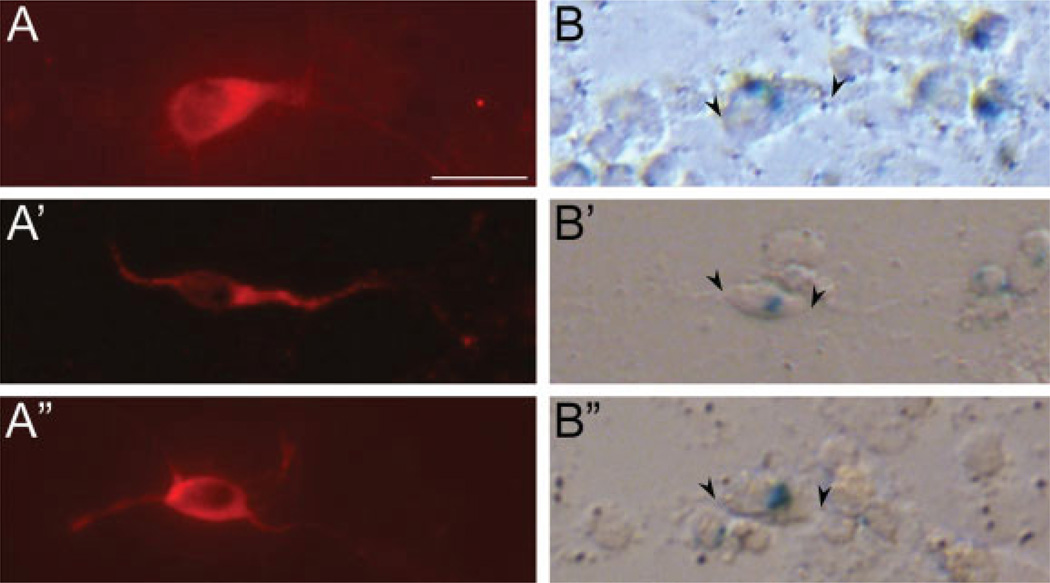

To determine whether the EphA5 receptor was expressed specifically in the dopaminergic neurons, dissociated midbrain cultures from E12.5 EphA5LacZ/+ embryos were immunostained with anti-TH antibody [Fig. 3(A)] and treated with X-gal [Fig. 3(B)]. Quantification of the cell cultures showed that at least 85% of TH-positive neurons colocalized with EphA5 expression, indicating that EphA5 is expressed in the majority of midbrain dopaminergic neurons.

Figure 3.

EphA5 expression in dopaminergic neurons. (A,B), (A’,B’), and (A”,B”) Three dopaminergic neurons which also express EphA5 receptor. E12.5 EphA5LacZ/+ midbrains were dissociated, plated, and reacted with rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (A,A’,A”) to identify dopaminergic neurons in the mixed culture and X-Gal (B,B’,B”) to reveal the presence of the EphA5 receptor in dopaminergic neurons. The X-gal positive neurons are flanked by arrowheads. Approximately 85% of dopaminergic neurons expressed EphA5. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Effects of Ephrin-A5 on Midbrain Dopaminergic Axon Growth

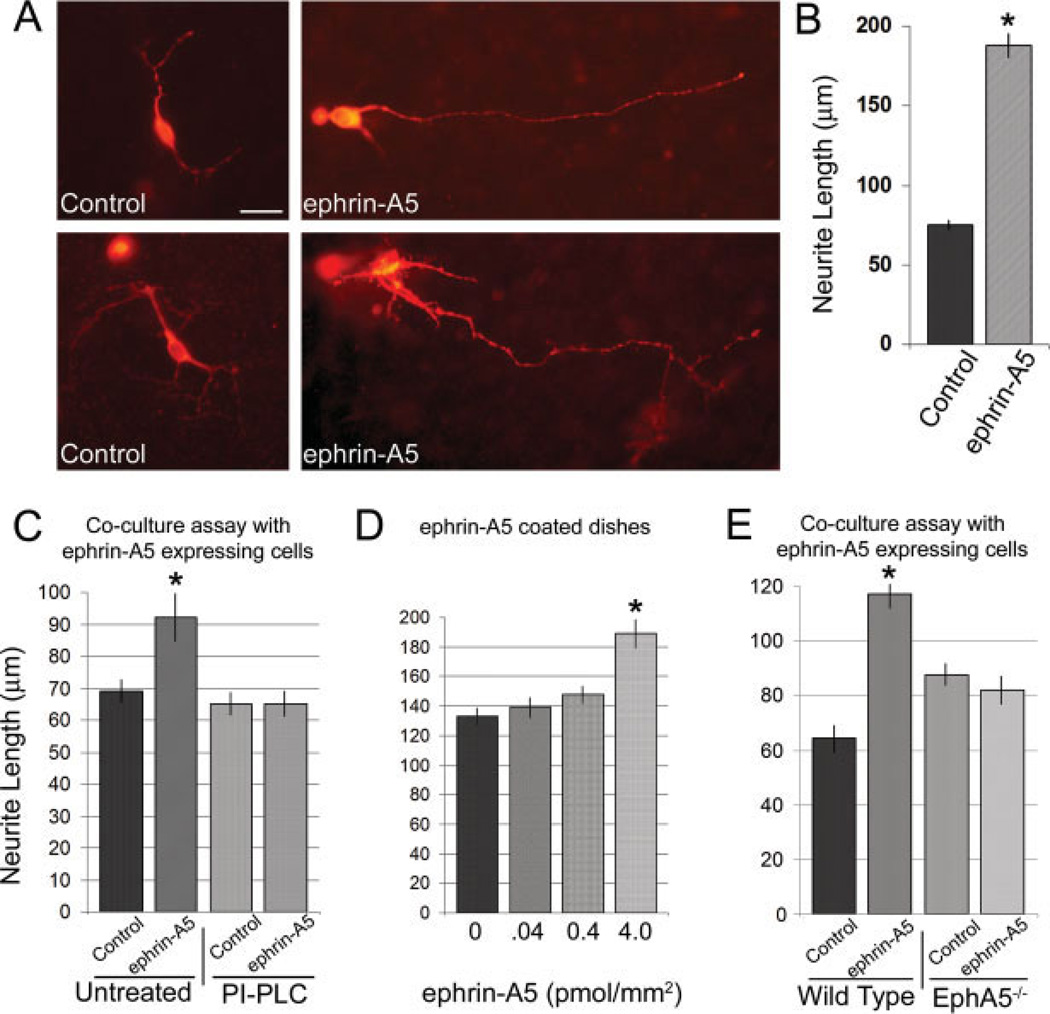

To critically examine the possibility that ephrin-A5 regulates the development of the midbrain dopaminergic pathways, we tested the effects of the ligand on dopaminergic neurons. Ventral midbrain neurons from the E14 rat were dissociated and plated for 48 or 72 h over a carpet of NIH3T3 cells with or without ephrin-A5 expression. Dopaminergic neurons were identified in culture through fluorescent labeling with anti-TH antibody. Neurite length over the ephrin-A5 expressing cells was 34% longer at 48 h and 147% longer at 72 h than over control cells [Fig. 4(A–C)], suggesting that ephrin-A5 promotes neurite growth. Three independent ephrin-A5 expressing cell lines were tested, and similar results were obtained (not shown).

Figure 4.

Ephrin-A5 promotes neurite outgrowth from the midbrain dopaminergic neurons. (A) Dopaminergic neuron coculture with ephrin-A5 expressing cell lines. Dissociated E12 rat midbrain cells were grown over a monolayer of either control NIH3T3 cells or ephrin-A5 expressing cells for 72 h. TH positive neurons exhibited significantly longer and more complex neurites when exposed to the ligand. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Quantification of neurite length. A 2.5-fold increase in the length of TH-positive neurites was found in neurons cocultured with ephrin-A5 over the control. NControl = 221 neurons and Nephrin-A5 = 160 neurons. *Indicates significance, t-test, p < 0.0001. Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) Enhanced neurite outgrowth requires functional ephrin-A5. Cocultures were pretreated with 0.8 U/mL of PI-PLC, an enzyme which cleaves the GPI linked ephrin-A5 from the cell line. Without ligand, the length of rat neurites grown over ephrin-A5 expressing cells for 48 h was similar to controls. (D) Ephrin-A5-Fc substrate promotes dopaminergic neurite outgrowth. Plates were coated with either crosslinked ephrin-A5 Fc-IgG or IgG alone prior to the seeding of the dissociated midbrain neurons. Neurons were allowed to culture for 48 h. Higher concentrations of ephrin-A5 correlate with longer neurite outgrowth. (E) EphA5 kinase activity is required for the enhanced dopaminergic outgrowth. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons from E12.5 EphA5LacZ/LacZ mouse embryos were no longer responsive to the presence of ephrin-A5. Wild-type dopaminergic neurons containing functional EphA5 receptor grew long neurites over ephrin-A5. Mouse neurons were cultured for 48 h. Panels (C–E): N = 90–200 neurons per category. *Indicates significance, t-test, p < 0.01. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

To be certain that the effects on dopaminergic neurite outgrowth were due to ephrin-A5 expression and not due to other undefined events, cell lines were treated with PI-PLC to remove ephrin-A5, which is anchored to the cell membrane by a GPI linkage. The cell cultures were treated with 0.8 U/mL of PI-PLC prior to plating the dissociated midbrain neurons from rat and then examined for the effects of this treatment after 48 h. The stimulatory effect observed on dopaminergic neurons was reduced to control levels in the treated cultures [Fig. 4(C)]. In another control, we further tested ephrin-A5 effects on dopaminergic neurite outgrowth using purified ephrin-A5 to ensure that the stimulatory effects were not due to nonspecific cell line artifacts. Enhanced neurite outgrowth was still observed when dopaminergic neurons were grown over a substrate of purified ephrin-A5 for a 48 h period [Fig. 4(D)]. In addition, neurite length was increasingly longer with increasing concentrations of the ligand and was greatest at the highest ephrin-A5 concentration of 4 pmol/mm2.

To determine whether the activity observed by midbrain dopaminergic neurons was mediated through the EphA5 receptor, the effects of ephrin-A5 on the midbrain dopaminergic neurons from EphA5LacZ/LacZ mice, in which the kinase domain was replaced with β-galactosidase, were examined. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons from either E12.5 wild type or EphA5LacZ/LacZ animals were each plated over the control and ephrin-A5 expressing cells for a 48-h period. Only wild-type midbrain neurons were able to exhibit the enhanced extension [Fig. 4(E)] in the presence of ephrin-A5, indicating that EphA5 receptor kinase activity is required for the effect.

Preferential Binding of the Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons to Striatal Slices with Ephrin-A5 Expression

The expression of ephrin-A5 in the striatum and EphA5 in the midbrain dopaminergic neurons and the stimulatory effects of the ligand on dopaminergic axon growth suggest possible adhesive interactions which promote dopaminergic targeting in the striatum. If this were true, one would anticipate that the midbrain dopaminergic neurons bind to the striatum more readily where ephrin-A5 is expressed, and that the loss of ephrin-A5 would lead to a reduction of cell attachment. To test this idea, wild-type E12.5 mouse midbrain dopaminergic neurons were plated on striatal slices from either wild type or ephrin-A5−/− animals. To facilitate detection of the attached cells, the midbrain neurons were obtained from embryos of mice that carry a GFP transgene under the control of a TH promoter (Matsushita et al., 2002). Previous studies have shown that the TH promoter drives GFP expression primarily in dopaminergic neurons and GFP serves as a convenient marker for these cells. Dissociated E12.5 midbrain neurons from TH-GFP mice were plated over striatal slices from either wild-type or ephrin-A5−/− animals [Fig. 5(A)]. Fewer than half of the TH positive cells were attached to striatal slices lacking ephrin-A5 compared with wild-type slices [Fig. 5(B)], which demonstrates that endogenous ephrin-A5 had an adhesive effect on midbrain dopaminergic neurons. This suggests that without the ligand, EphA5 expressing dopaminergic neurons may not recognize their striatal targets as effectively.

Figure 5.

Loss of adhesion of dopaminergic neurons on striatal slices lacking ephrin-A5. (A) A schematic showing the experimental design. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons from E12.5 THGFP mice were dissociated and plated onto 100 µm striatal slices from either wild type (N = 38) or ephrin-A5−/− (N = 26) adult mouse brains. (B) Quantification of the number of TH positive neurons bound to the striatum. Fewer GFP positive cells adhered to ephrin-A5−/− striatal slices. *Indicates significance, t-test, p = 0.0007.

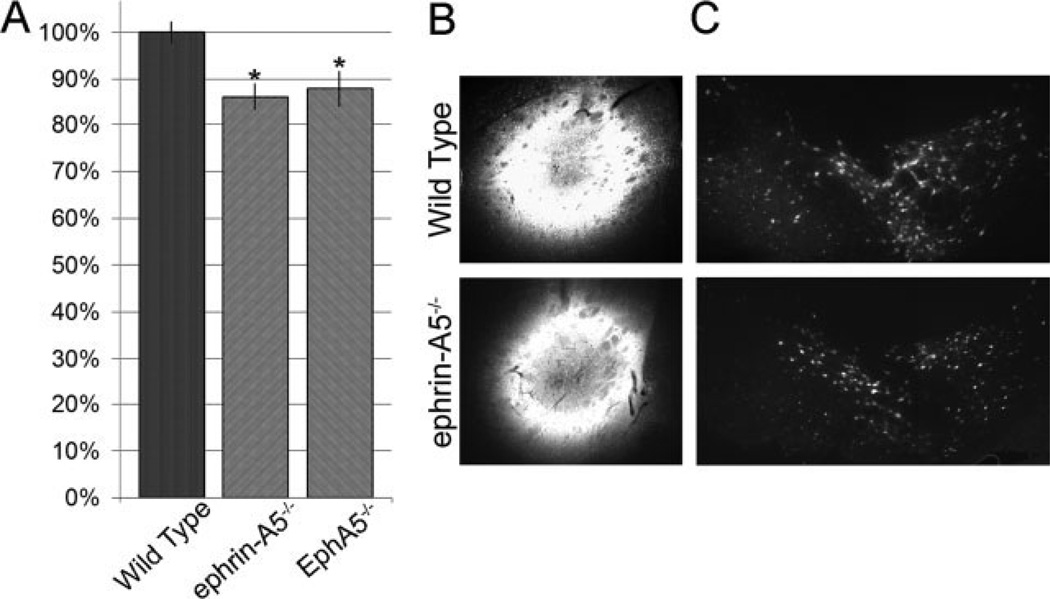

Reduction of Striatal Targeting by the Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons in Mice Lacking Ephrin-A5 or EphA5

To critically examine the roles of ephrin-A5 and EphA5 in vivo, wild type, ephrin-A5−/−, and EphA5LacZ/LacZ mice were analyzed for striatal targeting by the midbrain neurons using retrograde axon tracing. A retrograde axon tracer, fluorogold, was injected into the mid-striatum of adult mice which is taken up by the axons and carried back to the cell bodies located in the midbrain. Ephrin-A5−/− mutant mice exhibited a 14% decrease in the number of fluorogold labeled midbrain neurons [Fig. 6]. The total number of midbrain dopaminergic neurons was not changed in the mutant animals (not shown) suggesting that the decrease in retrogradely labeled cells is likely due to a targeting defect. Analysis of EphA5LacZ/LacZ mice showed that they were similarly affected, indicating that it may mediate the function of ephrin-A5.

Figure 6.

Decreased axon targeting to the striatum by the midbrain dopaminergic neurons in mice lacking EphA5 or ephrin-A5. (A) Reduction of retrogradely labeled midbrain neurons by Fluorogold injected in the striatum of the knockout mice. NWild type = 6, Nephrin-A5−/− = 11, NEphA5LacZ/LacZ = 9, * indicates significance, t-test, p < 0.03. (B) Fluorogold injection sites. Only brains with comparable injection size and position as confirmed by histological examinations were used in the quantification. (C) Typical retrogradely labeled midbrain dopaminergic neurons. All sections through the midbrain were analyzed.

DISCUSSION

During development, axons face the daunting task of forming proper connections with targets that are monumentally distant from their cell bodies. Ephrin-A5 and EphA5 expression patterns suggested a potential role in the development of the midbrain dopaminergic neurons. EphA5, a receptor for ephrin-A5, was found to be expressed in the ventral midbrain and in the dopaminergic cells. Meanwhile, ephrin-A5 was found in both the caudate/putamen as well as the nucleus accumbens. The expression of ephrin-A5 in the striatum pointed to a possibly novel function in regulating the proper targeting of dopaminergic axons. Our model suggests that the ligand expression in the striatum may help maintain proper midbrain dopaminergic connections through adhesive forces as opposed to inhibitory ones. This led us to investigate how these two molecules could interact and affect the development of the pathway. In vitro, the midbrain dopaminergic neurons grow longer neurites in the presence of ephrin-A5. Additionally, the stimulatory effect was regulated through the EphA5 receptor and required its kinase activity. On striatal sections, the target tissue of the midbrain dopaminergic fibers, fewer neurons were bound in the absence of ephrin-A5, indicating that ephrin-A5 serves to adhere the midbrain dopaminergic neurons. In vivo, a 14% decrease in retrogradely labeled neurons was found in ephrin-A5−/− mice suggesting a targeting deficit. As there is no apparent change in the number of total midbrain dopaminergic neurons (data not shown), the reduction is likely due to fewer midbrain neurons innervating the striatum. Many axon guidance molecules, with overlapping functions, act upon this pathway during development (Yue et al., 1999; Lin and Isacson, 2006), which may explain the relatively mild defects in the mutant animals.

Although ephrins have been shown to exert mostly inhibitory effects on axons and dendrites, a few studies have reported neurotrophic effects (Gao et al., 2000; Holmberg et al., 2000; Hansen et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2006). This study provides additional evidence of the positive effects the Eph family of molecules can elicit. In fact, recent evidence indicates that most inhibitory axon guidance molecules can have dual effects (Dickson, 2002). For example, the repulsive axon guidance cue, Slit, has been shown to promote branching and elongation of DRG axons (Zinn and Sun, 1999); likewise, Semaphorins, which are generally repulsive, can have attractive effects (Hansen et al., 2004; Kantor et al., 2004; Hernandez-Montiel et al., 2008). Ephrin-A5 has been shown to dictate both positive and inhibitory effects on separate populations of motor neurons in the limb bud (Eberhart et al., 2004). Although the mechanisms are unclear, retinal axons in vitro exhibited either inhibitory or attractive behavior in response to varying concentrations of ephrin-A5 exposure (Hansen et al., 2004). Cis interactions between EphA3 and ephrin-A5 have also been reported as a means of silencing the inhibitory effects of the Eph receptor (Carvalho et al., 2006).

Ascending Midbrain Dopaminergic Axon Pathfinding

Axon pathfinding requires a coordinated effort by multiple guidance cues. Neurite outgrowth, navigation, and target selection of the ascending midbrain dopaminergic axons is in all probability mediated by multiple ligand-receptor systems including slits, semaphorins, and netrins in addition to the Eph family of receptors (Nakamura et al., 2000; Gates et al., 2004).

Brain regions located in and around the ascending dopaminergic pathways have been shown to regulate the trajectories of the midbrain axons (Gates et al., 2004). Following the induction and migration of dopaminergic neurons, short axons begin to extend dorsally and then make a turn rostrally away from the ventral midbrain (Nakamura et al., 2000). The repulsive activity in the brain stem has been hypothesized to orient the axons rostrally. However, rostral turning also appears to be under the influence of polarized substrates just dorsal of the ventral midbrain (Nakamura et al., 2000). Explant assays in which the dorsal mesencephalon was flipped relative to the ventral mesencephalon led to neurites turning in the opposite direction suggesting that a gradient of an as yet unidentified guidance cue is present. The chemorepulsive guidance molecules, the Slits, may also be a driving force in the initial exit of the midbrain neurites toward the ganglionic eminence and in the prevention of midline crossing (Hu, 1999; Lin et al., 2005; Lin and Isacson, 2006). Slit1 is expressed early along the ventral midline of the brain including the mesencephalon. In addition, the Slit receptor, Robo, is expressed in the midbrain dopaminergic neurons themselves. Dopaminergic axons are misrouted, in some instances crossing over the midline and traversing the hypothalamus instead of straight to the forebrain targets in Slit1/2 double knockout mice (Bagri et al., 2002). Other unknown attractive cues also play a role in the pathfinding of midbrain dopaminergic axons. At the time that axons extend rostrally, between E12 and E13, explants from the ganglionic eminence/striatum and the medial forebrain bundle are highly attractive to these neurons (Gates et al., 2004; Jaumotte and Zigmond, 2005).

By E18 in the mouse, projection pathways from the midbrain dopaminergic neurons to the forebrain targets are basically established (Hu et al., 2004). Similar to the brain stem tissue, cerebral cortical explants repelled the midbrain dopaminergic axons, suggesting a function to restrict the axon terminals in the striatum. In addition, strong attractive activity was detected in embryonic striatal tissue, the target of the midbrain dopaminergic axons (Gates et al., 2004). The attractive activities appear to be temporally regulated to correlate with the arrival of the midbrain dopaminergic axons. The outgrowth into the ganglionic eminence is initially widespread with no distinct specificity (Hu et al., 2004). These results indicate that the early axons from the midbrain cover an extensive region with many collaterals in the striatum. Gradually, these connections become specialized and by E17 in the mouse, fibers extending from the midbrain have partially segregated into separate bundles to become the mesostriatal and mesolimbic tracts (Hu et al., 2004). Pruning of mislocated collaterals is likely to confer specificity in the later stages of development. Ephrin-B2 is expressed in the striatum in a dorsolateral to ventromedial gradient and may play a role in the specification of DA axon terminal positions (Yue et al., 1999).

A Role for the Eph Family of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

In this study, the EphA5/ephrins-A5 ligand-receptor pair has been implicated in the development of midbrain dopaminergic axon targeting. EphA5 was expressed across the entire ventral midbrain and in most midbrain dopaminergic neurons. In situ hybridization analysis in the striatum revealed high transcription of ephrin-A5 in the dorsolateral and ventromedial striatum. In vivo studies suggest that ephrin-A5 elicits a positive effect upon midbrain dopaminergic axon termination. Consistent with the studies reported here, a transgenic mouse expressing a soluble EphA receptor in mice was shown to reduce striatal targeting by 40% in dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons (Seiber et al., 2004). In addition to ephrin-A5, dopaminergic axons can also be attracted by other traditionally inhibitory cues such as Sema 3A (Hernandez-Montiel et al., 2008).

Beyond development, Eph/ephrin signaling may also have a role in neurotransmission and plasticity. As shown, EphA5 expression remains robust throughout adulthood and ephrin-A5 expression is also retained into adulthood (not shown). Drug addiction studies suggest that the Eph/ephrin system may play a significant role in mediating behavioral responses through expression. For example, ephrin-B2 expression, which is higher in the nucleus accumbens, responds to cocaine or amphetamine administration by upregulating expression about 3-fold (Yue et al., 1999). Consistent with this report, disruption of the EphA function led to a 50% reduction in striatal dopamine levels, poor performance in behavioral learning paradigms (Halladay et al., 2004) and an arrested response to amphetamine administration (Seiber et al., 2004).

The midbrain dopaminergic pathways are critically important for the integration of psychomotor and sensorimotor behavior. Understanding the mechanisms required for the proper development and maintenance of the ascending midbrain dopaminergic striatal targets may provide insight for future regenerative therapies to combat Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Science Foundation; contract grant number: 0548561.

Contract grant sponsor: Michael J Fox Foundation.

We thank Dr. George Wagner for stimulating discussions and assistance with animal care and Dr. Michael Matise for his scientific expertise and assistance in β-galactosidase staining.

REFERENCES

- Antonopoulos J, Dori I, Dinopoulos A, Chiotelli M, Parnavelas JG. Postnatal development of the dopaminergic system of the striatum in the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;110:245–256. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A, Marin O, Plump AS, Mak J, Pleasure SJ, Rubenstein JL, Tessier-Lavigne M. Slit proteins prevent midline crossing and determine the dorsoventral position of major axonal pathways in the mammalian forebrain. Neuron. 2002;33:233–248. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00561-5. [see comment]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Wills KV, Triarhou LC, Ghetti B. Time of neuron origin and gradients of neurogenesis in midbrain dopaminergic neurons in the mouse. Exp Brain Res. 1995;105:191–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00240955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang J, Kaneko M, Yamada J, Woods G, Stryker MP, Feldheim DA. Ephrin-A5 guide the formation of functional maps in the visual cortex. Neuron. 2005;48:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang J, Niell CM, Liu X, Pfeiffenberger C, Feldheim DA, Stryker MP. Selective disruption of one Cartesian axis of cortical maps and receptive fields by deficiency in ephrin-A5 and structured activity. Neuron. 2008;57:511–523. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho RF, Beutler M, Marler KJ, Knoll B, Becker-Barroso E, Heintzmann R, Ng T, et al. Silencing of EphA3 through a cis interaction with ephrinA5. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:322–330. doi: 10.1038/nn1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HJ, Nakamoto M, Bergemann AD, Flanagan JG. Complementary gradients in expression and binding of ELF-1 and Mek4 in development of the topographic retinotectal projection map. Cell. 1995;82:371–381. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstom A, Fuxe K. Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurones in the central nervous system. I. Demonstration of monoamines in the cell bodies of brain stem neurones. Acta Phys Scand. 1964;62:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy A, Soriano P. Ephrin signaling in vivo: Look both ways. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:1–10. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science. 2002;298:1959–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher U, Kremoser C, Handwerker C, Loschinger J, Noda M, Bonhoeffer F. In vitro guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons by RAGS, a 25 kDa tectal protein related to ligands for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1995;82:359–370. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart J, Barr J, O’Connell S, Flagg A, Swartz ME, Cramer KS, Tosney KW, et al. Ephrin-A5 exerts positive or inhibitory effects on distinct subsets of EphA4-positive motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1070–1078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4719-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, Nakamoto M, Osterfield M, Gale NW, DeChiara TM, Rohatgi R, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Loss-of-function analysis of EphA receptors in retinotectal mapping. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2542–2550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0239-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JG, Vanderhaeghen P. The ephrins and Eph receptors in neural development. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisen J, Yates PA, McLaughlin T, Friedman GC, O’Leary DD, Barbacid M. Ephrin-A5 (AL-1/RAGS) is essential for proper retinal axon guidance and topographic mapping in the mammalian visual system. Neuron. 1998;20:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Holland SJ, Valenzuela DM, Flenniken A, Pan L, Ryan TE, Henkemeyer M, et al. Eph receptors and ligands comprise two major specificity subclasses and are reciprocally compartmentalized during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1996;17:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao PP, Sun CH, Zhou XF, DiCicco-Bloom E, Zhou R. Ephrins stimulate or inhibit neurite outgrowth and survival as a function of neuronal cell type. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60:427–436. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000515)60:4<427::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao PP, Yue Y, Cerretti DP, Dreyfus C, Zhou R. Ephrin-dependent growth and pruning of hippocampal axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4073–4077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao PP, Yue Y, Zhang JH, Cerretti DP, Levitt P, Zhou R. Regulation of thalamic neurite outgrowth by the Eph ligand ephrin-A5: Implications in the development of thalamocortical projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5329–5334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao PP, Zhang JH, Yokoyama M, Racey B, Dreyfus CF, Black IB, Zhou R. Regulation of topographic projection in the brain: Elf-1 in the hippocamposeptal system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11161–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates MA, Coupe VM, Torres EM, Fricker-Gates RA, Dunnett SB. Spatially and temporally restricted chemo-attractive and chemorepulsive cues direct the formation of the nigro-striatal circuit. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:831–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halladay AK, Tessarollo L, Zhou R, Wagner GC. Neurochemical and behavioural deficits consequent to expression of a dominant negative EphA5 receptor. Mol Brain Res. 2004;123:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MJ, Dallal GE, Flanagan JG. Retinal axon response to ephrin-A5 shows a graded, concentration-dependent transition from growth promotion to inhibition. Neuron. 2004;42:717–730. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Montiel HL, Tamariz E, Sandoval-Minero MT, Varela-Echavarria A. Semaphorins 3A, 3C, and 3F in mesencephalic dopaminergic axon pathfinding. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:387–397. doi: 10.1002/cne.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Armulik A, Senti KA, Edoff K, Spalding K, Momma S, Cassidy R, et al. Ephrin-A2 reverse signaling negatively regulates neural progenitor proliferation and neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:462–471. doi: 10.1101/gad.326905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Clarke DL, Frisen J. Regulation of repulsion versus adhesion by different splice forms of an Eph receptor. Nature. 2000;408:203–206. doi: 10.1038/35041577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. Chemorepulsion of neuronal migration by Slit2 in the developing mammalian forebrain. Neuron. 1999;23:703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Cooper MA, Crockett DP, Zhou R. Differentiation of the midbrain dopaminergic pathways during mouse development. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:301–311. doi: 10.1002/cne.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaumotte JD, Zigmond MJ. Dopaminergic innervation of forebrain by ventral mesencephalon in organotypic slice co-cultures: Effects of GDNF. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;134:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor DB, Chivatakarn O, Peer KL, Oster SF, Inatani M, Hansen MJ, Flanagan JG, et al. Semaphorin 5A is a bifunctional axon guidance cue regulated by heparan and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. Neuron. 2004;44:961–975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinova I, Nikolova G, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Meda P, Kucera T, Zarbalis K, Wurst W, et al. EphA-Ephrin-A-mediated beta cell communication regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic islets. Cell. 2007;129:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Nishanian TG, Mood K, Bong YS, Daar IO. EphrinB1 controls cell-cell junctions through the Par polarity complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:979–986. doi: 10.1038/ncb1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim BK, Matsuda N, Poo MM. Ephrin-B reverse signaling promotes structural and functional synaptic maturation in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:160–169. doi: 10.1038/nn2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Isacson O. Axonal growth regulation of fetal and embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons by Netrin-1 and Slits. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2504–2513. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Rao Y, Isacson O. Netrin-1 and slit-2 regulate and direct neurite growth of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann F, Peuckert C, Dehner F, Zhou R, Bolz J. Ephrins regulate the formation of terminal axonal arbors during the development of thalamocortical projections. Development. 2002;129:3945–3955. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RC, Matthews GA, Gale NW, Yancopoulos GD, Mason CA. Axon guidance in the mouse optic chiasm: Retinal neurite inhibition by ephrin “A”-expressing hypothalamic cells in vitro. Dev Biol. 2000;221:132–147. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita N, Okada H, Yasoshima Y, Takahashi K, Kiuchi K, Kobayashi K. Dynamics of tyrosine hydroxylase promoter activity during midbrain dopaminergic neuron development. J Neurochem. 2002;82:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura SI, Ito Y, Shirasaki R, Murakami F. Local directional cues control growth polarity of dopaminergic axons along the rostrocaudal axis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4112–4119. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04112.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DD, McLaughlin T. Mechanisms of retino-topic map development: Ephs, ephrins, and spontaneous correlated retinal activity. Prog Brain Res. 2005;147:43–65. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polleux F, Ghosh A. The slice overlay assay: A versatile tool to study the influence of extracellular signals on neuronal development. Sci STKE. 2002;136:P19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.136.pl9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M. Motivational views of reinforcement: Implications for understanding the behavioral functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiber B-A, Kuzmin A, Canals JM, Danielsson A, Paratcha G, Arenas E, Alberch J, et al. Disruption of EphA/ephrin-A signaling in the nigrostriatal system reduces dopaminergic innervation and dissociates behavioural responses to amphetamine and cocaine. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Weiss F. The dopamine hypothesis of reward: Past and current status. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Geer P, Hunter T, Lindberg RA. Receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and their signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:251–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG. Multiple roles of EPH receptors and ephrins in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:155–164. doi: 10.1038/35058515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SE, Mann F, Erskine L, Sakurai T, Wei S, Rossi DJ, Gale NW, et al. Ephrin-B2 and EphB1 mediate retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm. Neuron. 2003;39:919–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Chen ZY, Gale NW, Blair-Flynn J, Hu TJ, Yue X, Cooper M, et al. Mistargeting hippocampal axons by expression of a truncated Eph receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10777–10782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162354599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Widmer DA, Halladay AK, Cerretti DP, Wagner GC, Dreyer JL, Zhou R. Specification of distinct dopaminergic neural pathways: Roles of the Eph family receptor EphB1 and ligand ephrin-B2. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2090–2101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02090.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JH, Cerretti DP, Yu T, Flanagan JG, Zhou R. Detection of ligands in regions anatomically connected to neurons expressing the Eph receptor Bsk: Potential roles in neuron-target interaction. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7182–7192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07182.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. The Eph family receptors and ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:151–181. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn K, Sun Q. Slit branches out: A secreted protein mediates both attractive and repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;97:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]