Abstract

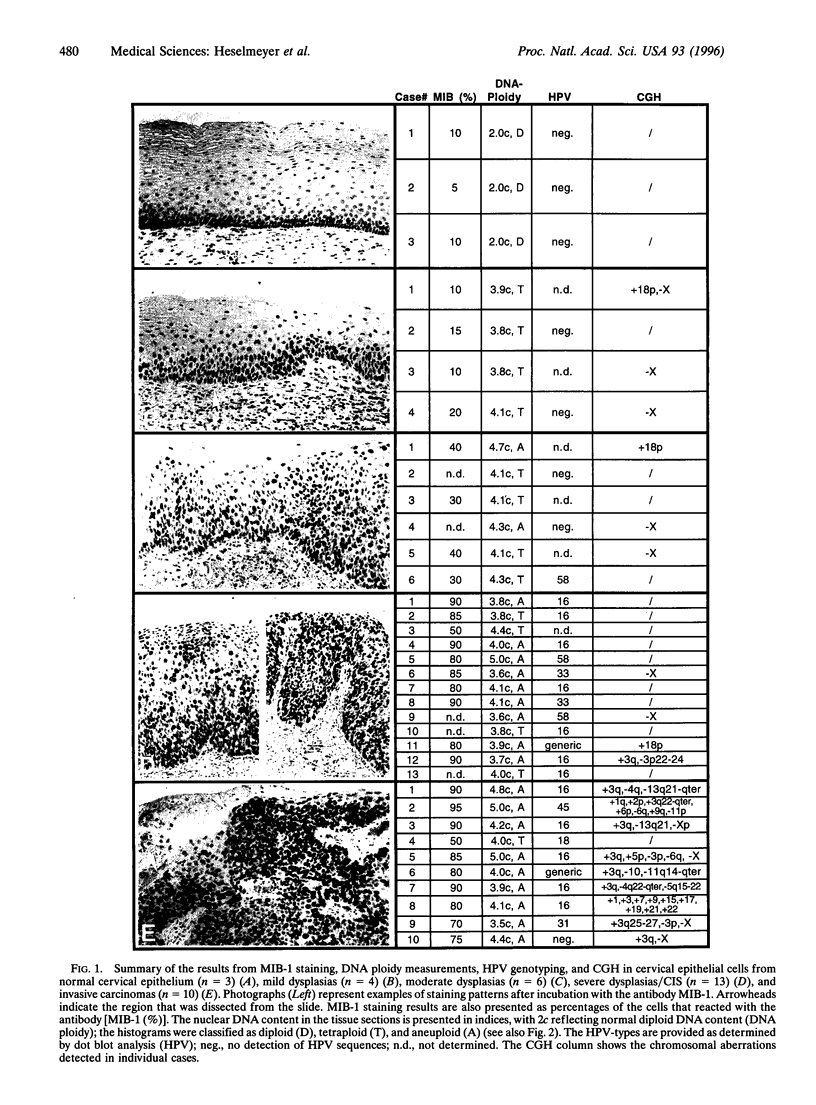

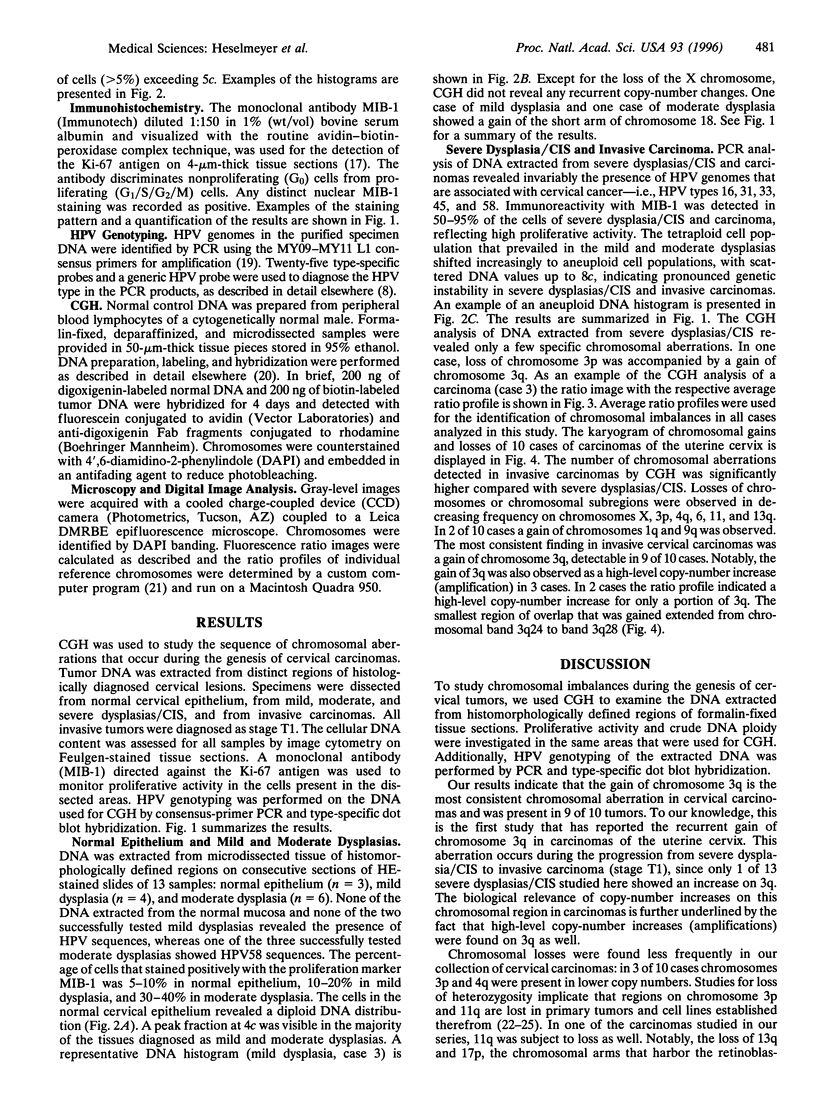

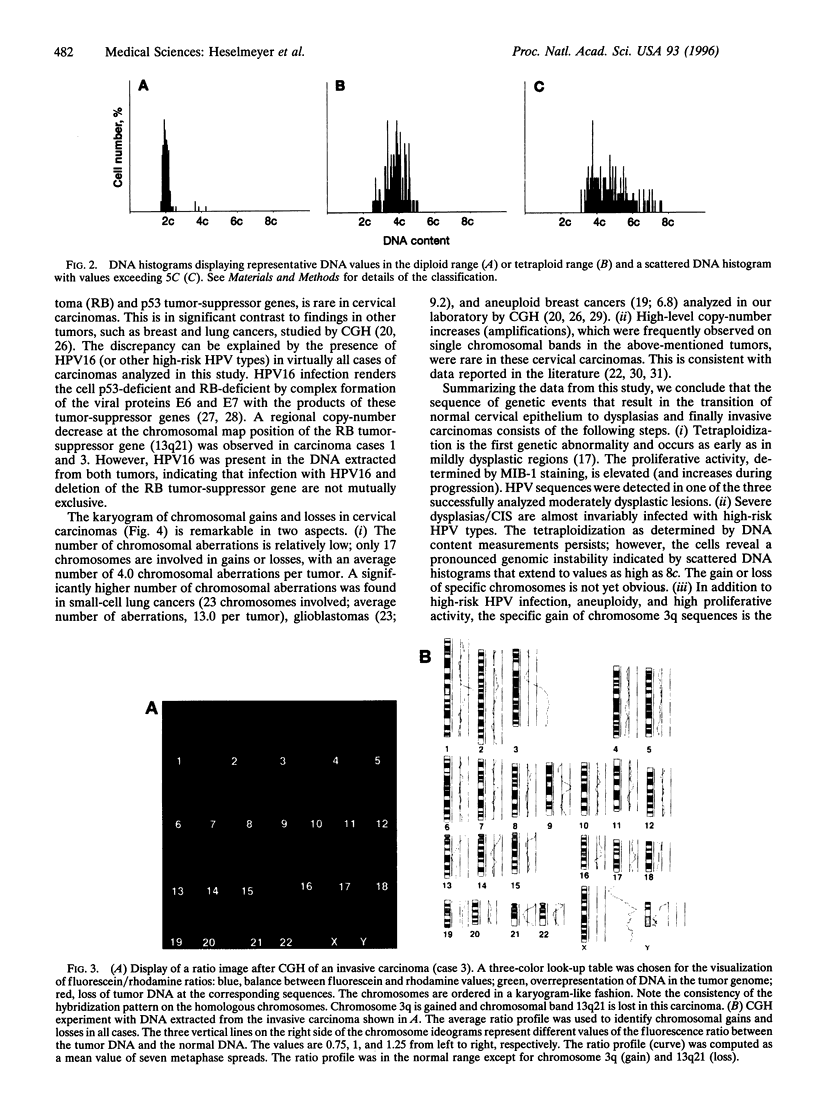

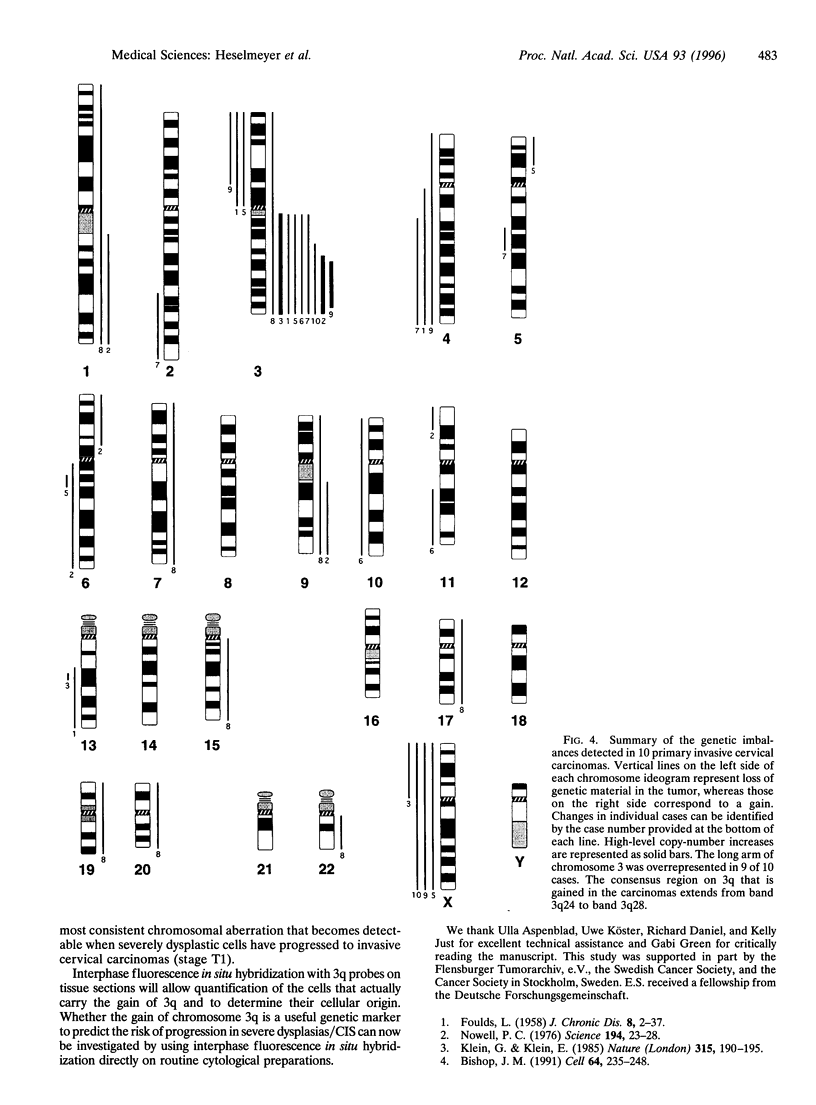

We have chosen tumors of the uterine cervix as a model system to identify chromosomal aberrations that occur during carcinogenesis. A phenotype/genotype correlation was established in defined regions of archived, formalin-fixed, and hematoxylin/eosin-stained tissue sections that were dissected from normal cervical epithelium (n = 3), from mild (n = 4), moderate (n = 6), and severe dysplasias/carcinomas in situ (CIS) (n = 13), and from invasive carcinomas (n = 10) and investigated by comparative genomic hybridization. The same tissues were analyzed for DNA ploidy, proliferative activity, and the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) sequences. The results show that an increase in proliferative activity and tetraploidization had occurred already in mildly dysplastic lesions. No recurrent chromosomal aberrations were observed in DNA extracted from normal epithelium or from mild and moderate dysplasias, indicating that the tetraploidization precedes the loss or gain of specific chromosomes. A gain of chromosome 3q became visible in one of the severe dysplasias/CIS. Notably, chromosome 3q was overrepresented in 90% of the carcinomas and was also found to have undergone a high-level copy-number increase (amplification). We therefore conclude that the gain of chromosome 3q that occurs in HPV16-infected, aneuploid cells represents a pivotal genetic aberration at the transition from severe dysplasia/CIS to invasive cervical carcinoma.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Atkin N. B., Baker M. C., Fox M. F. Chromosome changes in 43 carcinomas of the cervix uteri. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1990 Feb;44(2):229–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(90)90052-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer G., Askensten U., Ahrens O. Cytophotometry. Hum Pathol. 1989 Jun;20(6):518–527. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J. M. Molecular themes in oncogenesis. Cell. 1991 Jan 25;64(2):235–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90636-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch F. X., Manos M. M., Muñoz N., Sherman M., Jansen A. M., Peto J., Schiffman M. H., Moreno V., Kurman R., Shah K. V. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Jun 7;87(11):796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson N., Howley P. M., Münger K., Harlow E. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989 Feb 17;243(4893):934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOULDS L. The natural history of cancer. J Chronic Dis. 1958 Jul;8(1):2–37. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(58)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon E. R., Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990 Jun 1;61(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg I. Chromosomes in preinvasive, microinvasive and invasive cervical carcinoma. Hereditas. 1971;68(2):165–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1971.tb02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton G. M., Penny L. A., Baergen R. N., Larson A., Brewer C., Liao S., Busby-Earle R. M., Williams A. W., Steel C. M., Bird C. C. Loss of heterozygosity in cervical carcinoma: subchromosomal localization of a putative tumor-suppressor gene to chromosome 11q22-q24. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Jul 19;91(15):6953–6957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildesheim A., Schiffman M. H., Gravitt P. E., Glass A. G., Greer C. E., Zhang T., Scott D. R., Rush B. B., Lawler P., Sherman M. E. Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection among cytologically normal women. J Infect Dis. 1994 Feb;169(2):235–240. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesudasan R. A., Rahman R. A., Chandrashekharappa S., Evans G. A., Srivatsan E. S. Deletion and translocation of chromosome 11q13 sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. Am J Hum Genet. 1995 Mar;56(3):705–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi A., Kallioniemi O. P., Sudar D., Rutovitz D., Gray J. W., Waldman F., Pinkel D. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science. 1992 Oct 30;258(5083):818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G., Klein E. Evolution of tumours and the impact of molecular oncology. Nature. 1985 May 16;315(6016):190–195. doi: 10.1038/315190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A. B., Murty V. V., Pratap M., Sodhani P., Chaganti R. S. ERBB2 (HER2/neu) oncogene is frequently amplified in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1994 Feb 1;54(3):637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell P. C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976 Oct 1;194(4260):23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka K., Nakano T., Arai T. c-erbB-2 Oncoprotein expression is associated with poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer. 1994 Feb 1;73(3):664–671. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<668::aid-cncr2820730327>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu N. C., DiPaolo J. A. Cytogenetics of cervical neoplasia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1992 Jun;60(2):214–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(92)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried T., Just K. E., Holtgreve-Grez H., du Manoir S., Speicher M. R., Schröck E., Latham C., Blegen H., Zetterberg A., Cremer T. Comparative genomic hybridization of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded breast tumors reveals different patterns of chromosomal gains and losses in fibroadenomas and diploid and aneuploid carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1995 Nov 15;55(22):5415–5423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried T., Petersen I., Holtgreve-Grez H., Speicher M. R., Schröck E., du Manoir S., Cremer T. Mapping of multiple DNA gains and losses in primary small cell lung carcinomas by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1994 Apr 1;54(7):1801–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M., Werness B. A., Huibregtse J. M., Levine A. J., Howley P. M. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell. 1990 Dec 21;63(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröck E., Thiel G., Lozanova T., du Manoir S., Meffert M. C., Jauch A., Speicher M. R., Nürnberg P., Vogel S., Jänisch W. Comparative genomic hybridization of human malignant gliomas reveals multiple amplification sites and nonrandom chromosomal gains and losses. Am J Pathol. 1994 Jun;144(6):1203–1218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher M. R., du Manoir S., Schröck E., Holtgreve-Grez H., Schoell B., Lengauer C., Cremer T., Ried T. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded solid tumors by comparative genomic hybridization after universal DNA-amplification. Hum Mol Genet. 1993 Nov;2(11):1907–1914. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.11.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivatsan E. S., Misra B. C., Venugopalan M., Wilczynski S. P. Loss of heterozygosity for alleles on chromosome II in cervical carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 1991 Oct;49(4):868–877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbeck R. G., Heselmeyer K. M., Moberger H. B., Auer G. U. The relationship between proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), nuclear DNA content and mutant p53 during genesis of cervical carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 1995;34(2):171–176. doi: 10.3109/02841869509093952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota J., Tsukada Y., Nakajima T., Gotoh M., Shimosato Y., Mori N., Tsunokawa Y., Sugimura T., Terada M. Loss of heterozygosity on the short arm of chromosome 3 in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1989 Jul 1;49(13):3598–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Manoir S., Schröck E., Bentz M., Speicher M. R., Joos S., Ried T., Lichter P., Cremer T. Quantitative analysis of comparative genomic hybridization. Cytometry. 1995 Jan 1;19(1):27–41. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Manoir S., Speicher M. R., Joos S., Schröck E., Popp S., Döhner H., Kovacs G., Robert-Nicoud M., Lichter P., Cremer T. Detection of complete and partial chromosome gains and losses by comparative genomic in situ hybridization. Hum Genet. 1993 Feb;90(6):590–610. doi: 10.1007/BF00202476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H. Disrupted dichotomous intracellular control of human papillomavirus infection in cancer of the cervix. Lancet. 1994 Apr 16;343(8903):955–957. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]