Abstract

Mouse superficial superior colliculus (SuSC) contains dense GABAergic innervation and diverse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Pharmacological and genetic approaches were used to investigate the subunit compositions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) expressed on mouse SuSC GABAergic terminals. [125I]-Epibatidine competition binding studies revealed that the α3β2* and α6β2* nicotinic subtype-selective peptide α-conotoxinMII blocked binding to 40 +/- 5% of SuSC nAChRs. Acetylcholine-evoked [3H]-GABA release from SuSC crude synaptosomal preparations is calcium dependent, blocked by the voltage-sensitive calcium channel blocker, cadmium, and the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine, but is unaffected by muscarinic, glutamatergic, P2X and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Approximately 50% of nAChR-mediated SuSC [3H]-GABA release is inhibited by α-conotoxinMII. However, the highly-α6β2*-subtype-selective α-conotoxinPIA did not affect [3H]-GABA release. Nicotinic subunit-null mutant mouse experiments revealed that ACh-stimulated SuSC [3H]-GABA release is entirely β2 subunit-dependent. α4 subunit deletion decreased total function by >90%, and eliminated α-conotoxinMII-resistant release. ACh-stimulated SuSC [3H]-GABA release was unaffected by β3, α5 or α6 nicotinic subunit deletions. Together, these data suggest that a significant proportion of mouse SuSC nicotinic agonist-evoked GABA-release is mediated by a novel, α-conotoxinMII-sensitive α3α4β2 nAChR. The remaining α-conotoxinMII-resistant, nAChR agonist-evoked SuSC GABA release appears to be mediated via α4β2* subtype nAChRs.

Keywords: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, GABA, synaptosome, subunit-null mutant, α-conotoxinMII, superior colliculus

Introduction

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are a heterogeneous population of transmembrane proteins belonging to the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. nAChRs are pentameric, containing either a combination of homologous α and β subunits, to form a heteromeric receptor or five copies of a single subunit, to form a homomeric receptor (Gotti et al. 2009). The subunits form a channel that is permeable to cations when activated by agonist binding at distal sites, thus contributing to neuronal excitability. Eight mammalian neuronal nAChR α (α2-7, α9-10) and three β (β2-4) subunits have been identified (Gotti et al. 2009). Many CNS nAChRs are located presynaptically, where they exert a neuromodulatory influence, promoting the release of neurotransmitters including dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, aspartate, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Dani & Bertrand 2007, Gotti et al. 2009).

The α4β2* nAChR subtype (* designates the possible presence of additional subunits (Lukas et al. 1999)) is the most abundant nAChR in mammalian brain, and binds nicotine and other agonists with high affinity (Whiting & Lindstrom 1987, Flores et al. 1992). The homomeric α7 nAChR, which binds α-bungarotoxin, is also widespread but with a distinctly different distribution from the α4β2* nAChR subtype (Clarke et al. 1985, Pauly et al. 1989, Schoepfer et al. 1990). A number of other receptor subtypes have also been identified, all with more restricted CNS distributions (Gotti et al. 2009). Of particular relevance to this study are the α6β2* and α3β2* nAChR subtypes that have a high affinity for the peptide antagonist α-conotoxin MII (α-CtxMII), and are found predominantly in dopaminergic and visual-tract regions, including the superior colliculus (Cartier et al. 1996, Whiteaker et al. 2000b, Gotti et al. 2005a). The subunit composition of midbrain dopaminergic-tract α-CtxMII-binding nAChRs has been extensively studied using nAChR subunit null mutant mice (Cui et al. 2003, Champtiaux et al. 2003, Marubio et al. 2003, Salminen et al. 2007, Salminen et al. 2004), as well as immunoprecipitation techniques (Gotti et al. 2005a, Zoli et al. 2002). These receptors include α6β2, α6β2β3 and α6α4β2β3 subtypes.

A dense population of α-CtxMII-binding nAChRs is also found along optic tract projections originating in the retina (Gotti et al. 2005b, Whiteaker et al. 2000b, Cox et al. 2008). In addition, α3 and α6 subunit mRNAs are expressed in the superficial layers of the superior colliculus (SuSC) (Whiteaker et al. 2000b). Using immunoprecipitation and enucleation techniques, the retina has been shown to produce large amounts of α6* nAChRs, yet only approximately 40% of SC high affinity α-CtxMII-binding nAChRs are expressed on retinal projections (Gotti et al. 2005b). This suggests that a substantial proportion of the α-CtxMII-sensitive (i.e. α3- or α6-containing) nAChRs in the SuSC are locally-expressed, rather than being found on projections from the retina. In addition, the SuSC contains some of the highest levels of GABA in the mammalian brain (Tsunekawa et al. 2005). In most brain regions, nAChR modulation of GABA release is mediated by α4β2* nAChRs (Lu et al. 1998). However, the colocalization of α6 and α3 nAChR subunit mRNAs, a local α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR population, and extremely rich GABAergic innervation in the SuSC suggested that this region could provide an unusual example of GABAergic neurotransmission that is modulated by α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs. This possibility is supported by several studies. In rats, visual responses originating in the SuSC are reduced by application of the nAChR agonist lobeline. This finding suggested that nAChR activation in the SuSC can increase inhibitory neurotransmitter release (Binns et al. 1999). Administration of nicotinic agonists to the SuSC also reduces colliculo-thalamic activity via activation of nAChRs on local GABAergic interneurons (Lee et al. 2001). Most pertinently for this study, α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs of unknown subtype regulate mouse SuSC GABA release (Endo et al. 2005).

In the present study, pharmacological and null mutant mouse approaches were used to confirm the existence, define the pharmacology, and determine the subunit composition of α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs residing on SuSC GABAergic terminals. The resulting data establish that stimulation of presynaptic nAChRs in the SuSC elicits calcium-dependent exocytosis of GABA, and that a substantial fraction of this release is mediated by a novel α-CtxMII-sensitive α3α4β2 nAChR subtype. This receptor has distinctly different properties from previously-characterized α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs expressed on dopaminergic terminals.

Materials and Methods

Materials

[3H]-GABA (50Ci/mmol) and [125I]-epibatidine (2200Ci/mmol) as well as Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail were purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). Acetylcholine, aminooxyacetic acid, atropine, cytisine, diisopropyl fluorophosphate, γ-aminobutyric acid, HEPES, sodium chloride, potassium chloride, magnesium sulfate, monobasic potassium phosphate, calcium chloride, EDTA, EGTA, aprotonin, pepstatin, leupeptin, sucrose, d-(+)-glucose, MK-801, CNQX, MDL-72222, TNP-ATP, NNC-711, mecamylamine, α-bungarotoxin, bovine serum albumin were obtained from SigmaAldrich (St. Louis, MO). α-Conotoxin MII (Cartier et al. 1996) and α-conotoxin PIA (Azam et al. 2005) were synthesized as previously described.

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6 and α4, α5, α6, β2 and β3 null mutant (wild type and homozygous null mutant) mice were utilized for biochemical assessment. All animals were bred and maintained in the animal facilities at the University of Colorado Institute for Behavioral Genetics, Boulder, CO, and were between 60 and 120 days old when used. The original sources of the null mutant animals were: Dr. Marina Piccioto (Yale University, New Haven, CT) (β2), Dr. John Drago (University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) (α4), Dr. Authur Beaudet (Baylor University College of Medicine, Houston, TX) (α5), Dr. Stephen Heinemann (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) (β3), and Dr. Uwe Maskos (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France) (α6). All of these mice have been backcrossed to C57BL/6J for at least 10 generations. Genotypes were determined prior to use as previously described (Salminen et al. 2004). Mice were housed in like-sexed sibling groups of no more than five individuals per cage, given ad lib access to food and water, and maintained on a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle. All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Colorado IACUC, and conform to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals set by the NIH.

Brain Region Dissection

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, the brain removed and placed on an ice-cold watch-glass. The superior colliculus (SC) was identified (visible from the dorsal side of the brain and directly anterior to the inferior colliculus). The SC was dissected away from the rest of the brain and placed on a chilled glass slide. The slide was placed under an American Optics 0.7-3× variable magnification dissection scope (Burlington, ON). The superficial layers appear as a distinct pinkish layer atop a whitish-colored core. The most caudal portion of the superficial layer was removed and saved (caudal portion SuSC). The outer superficial layers of the remaining structure were removed with a scalpel and microforceps, pooled with the initially removed caudal SuSC tissue and prepared for assessment. The SC core tissue was also retained for use in some experiments.

Membrane Preparations

To prepare membrane fractions for use in ligand binding studies, SuSC and SC core tissues were homogenized separately. Homogenization was performed in hypotonic buffer (homogenization buffer; 5 mM HEPES, 13.8 mM NaCl 0.24 mM KCl, 0.12 mM KH2PO4, 0.12 mM MgSO4,pH=7.5) to enhance lysis of cellular structures, while maintaining physiological pH. The initial homogenate was centrifuged at 10000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant discarded, the pellet resuspended in 2 ml fresh buffer, then re-centrifuged at 10000 × g for 10 min. This process was repeated two further times, before the pellet was resuspended in a 20× homogenization buffer with the addition of 1 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) to inactivate endogenous serine proteases. The homogenate was then centrifuged a final time at 10000 × g for 10 min, and the PMSF-containing supernatant discarded. This final pellet was then resuspended in 2ml deionized distilled water for immediate use in the binding assays. Protein content was determined using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard (Lowry et al. 1951).

[125I]-Epibatidine Binding

High affinity [125I]epibatidine binding experiments were performed as previously described (Whiteaker et al. 2000a), with minor modifications. Incubations were performed in 96-well polystyrene plates, with each reaction containing 10 μl each of radioligand, membrane preparation, and competing drug, for a total volume of 30 μl per well (final Binding Buffer concentration: 144 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 20 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA (w/v), 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 μg / ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin A to protect peptide ligands from destruction by endogenous proteases; pH = 7.5). The final concentration of [125I]-epibatidine (200 pM) was near saturation (Whiteaker et al. 2000a). Non-specific binding was defined by including 100 μM (-)-nicotine in the incubation. The experiments described here utilized 0.01 – 3000 nM α-CtxMII to discriminate between specific subtypes (α6β2*/α3β2* vs α4β2*) of high-affinity epibatidine binding sites (McIntosh et al. 2004, Whiteaker et al. 2000b, Cartier et al. 1996). Samples were incubated for 2 h at 23 °C, then for an additional 20 min at 4 °C. Binding was terminated by filtration onto polyethylenimine-soaked glass fiber filter plates using an Inotech Cell Harvester (Inotech Biosystems Intl, Inc., Rockville MD). The filter plate was rinsed 7 times with ice-cold wash buffer containing 144 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, and 20 mM HEPES, pH=7.5 and counted at 60% efficiency in a Wallac Trilux 1450 Microbeta liquid scintillation counter (Boston, MA) following addition of 100 μl of Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail.

Preparation and [3H]-GABA Loading of Crude Synaptosomes

Initial binding experiments indicated that α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs were only expressed in the superficial layers of the SC (see Figure 1). Accordingly, studies to measure α-CtxMII sensitive function were only performed in SuSC samples. The crude preparation containing synaptosomes (designated: crude synaptosomes) was formed by hand homogenization of SuSC tissue, in 0.32M sucrose buffered to pH = 7.5 by 10 mM HEPES, using a glass/Teflon homogenizer. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged once at 10000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet resuspended in 800 μl of uptake buffer (128 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 3.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM glucose). Crude synaptosomal preparations were incubated in uptake buffer supplemented with 1.25 mM aminooxyacetic acid (which inhibits GABA transaminase, preventing degradation of loaded [3H]-GABA) for 10 min at 37 °C. [3H]-GABA and unlabeled GABA were added to final concentrations of 0.1 and 0.25 μM, respectively, along with 50 μM diisopropyl fluorophosphate (an irreversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase). Incubation at 37 °C continued for another 10 min and, upon completion, 80 μl aliquots of sample were loaded onto 50mm diameter glass fiber filters for superfusion and measurement of [3H]-GABA release.

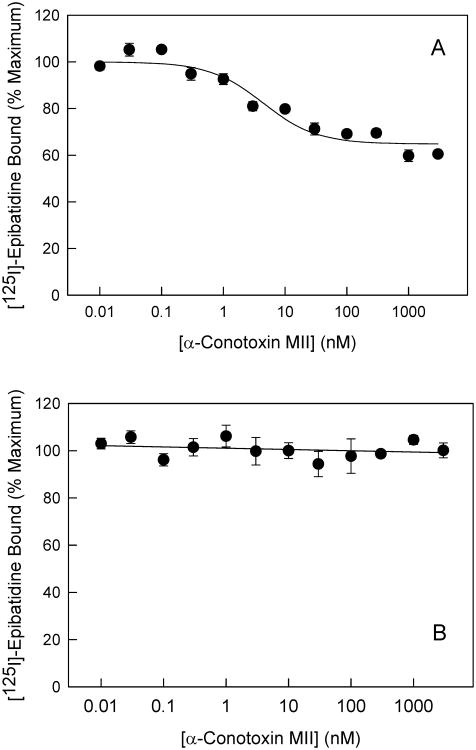

Figure 1. Heterogeniety of nAChR populations in the core and superficial tissues of the superior colliculus.

a, b, Inhibition of 200pM [125I]-epibatidine binding by α-CtxMII in the superficial and core layers of the SC, respectively. n = 3 for each point on the graph; points represent mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). The curve for the SuSC was calculated as described in the Methods.

Crude Synaptosomal Superfusion and [3H]-GABA Release

Crude synaptosomal superfusion and [3H]-GABA release was monitored using a 96-well plate collection format as previously described (McClure-Begley et al. 2009). Superfusion buffer consisted of uptake buffer supplemented with 1g/l BSA, 1 μM atropine (to prevent activation of muscarinic ACh receptors) and 100nM NNC-711 (to prevent GAT-1 transporter mediated GABA release). Filters containing [3H]-GABA-loaded crude synaptosomes were superfused at 0.7 ml/min for a 10 min wash period, then stimulated by a 16 s exposure to agonist. Any treatments prior to stimulated release were performed during the washout period. Fractions were collected from eight filters simultaneously, every 10 s, for 4 min (a total of 23 fractions per filter) into 96-well plates, using a Gilson FC 204 fraction collector (Middleton, WI). Scintillation cocktail (OptiPhase Supermix, 150μl/well) was added to each well, the plate sealed with clear adhesive tape and radiation content measured in a Wallac Trilux 1450 Microbeta liquid scintillation counter at 45% efficiency (Perkin Elmer; Boston, MA).

Data Analysis

Radioligand Binding

Specific CPM were converted to fmol/mg protein for use in the data analysis. Results of inhibition of [125I]-epibatidine binding were calculated using the general formula B = B0/(1+I/IC50), where B is the amount of ligand bound at a competitor concentration (I), B0 is the binding the the absence of inhibitor and IC50 is the amount of competitive ligand needed to eliminate 50% of binding, When multiple binding sites were detected, the following two-site equation was used to fit binding data: B = [B1/(1+S/K1)] +BR where B is ligand bound in the presence of inhibitor I, BI represents binding to receptors sensitive to inhibition with a sensitivity of IC50, and BR is any remaining ligand binding that is insensitive to inhibition.

Neurotransmitter Release

For each 23-fraction release set collected per filter, basal [3H]-GABA release was calculated from fractions collected before and after agonist exposure by single exponential decay. This basal release was then subtracted from the values taken during agonist exposure to calculate nAChR-evoked [3H]-GABA release. Evoked release was expressed as a multiple of baseline release. By normalizing the release values in this manner, it is possible to correct for any variation in [3H]-GABA content during the loading process, or number of viable crude synaptosomes in the sample. Biphasic concentration-response curves for stimulation of [3H]-GABA release by ACh were analyzed with SigmaPlot by fitting data to a 4 parameter hyperbolic equation: V′ = (V*S)/(K+S)+(v*S)/(k+S), where V′ is the release measured at each ACh concentration (S), maximum release due to activation of high- and low-ACh sensitive receptors is represented by V and v, respectively, and half-maximally-effective drug concentrations are represented by K and k, respectively. Monophasic dose-response relationships were analyzed with SigmaPlot by fitting data to a 2 parameter, hyperbolic equation: V′ = (V*S)/(K+S). For experiments measuring functional recovery of ACh-evoked [3H]-GABA release following exposure to α-CtxMII, data were fit to a first-order rise to maximum equation of the form: Vt = V*(1-e-bx) + VR, where the variables are Vt the function measured at time (t), with function at t = 0 (the non-inhibited activity, VR), recoverable function (V), and the recovery constant (k). Half maximal recovery was then calculated from t1/2=ln(2)/k.

Data analysis

Results from multiple determinations are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by either Student's unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc analysis, with p < 0.05 considered as significant.

Results

High affinity [125I]-epibatidine binding in SuSC

Specific [125I]epibatidine binding was particularly prevalent in the SuSC, with maximal binding (Bmax) shown to be 100 ± 2 fmol/mg. In addition, 40.2 ± 5.2% of specific [125I]epibatidine binding in the SuSC was sensitive to inhibition by α-CtxMII (Fig 1A). α-CtxMII inhibition of [125I]epibatidine binding to SuSC membranes had an IC50 of 0.22 ± 0.09nM. The α-CtxMII IC50 for the resistant sites could not be determined within the concentration range used, but is estimated to be >1 μM). In contrast to SuSC, [125I]-epibatidine binding in SC core tissue membranes exhibited a Bmax = 56 ± 2 fmol/mg and was not inhibited by α-CtxMII at concentrations below 1 μM (Fig 1B).

Sensitivity of [3H]-GABA Release from SuSC to α-CtxMII

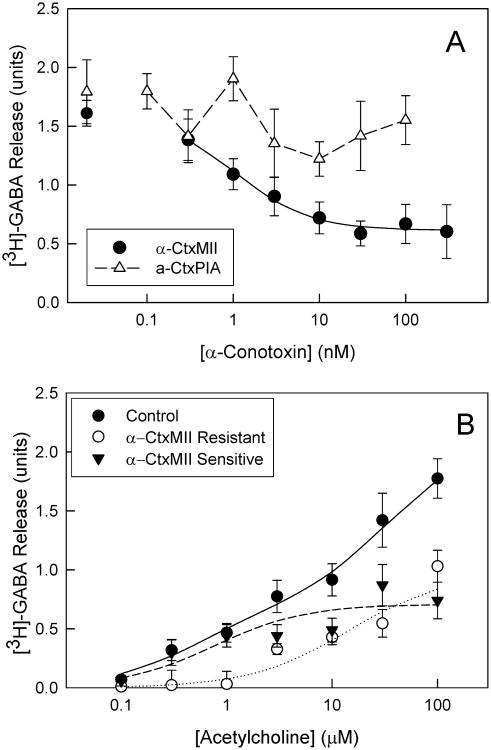

The [125I]-epibatidine binding results indicated that only SuSC contained α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs. Accordingly, only SuSC tissue was examined for α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR-mediated [3H]-GABA release. [3H]-GABA release was stimulated by 100 μM ACh, and the effects of α-CtxMII (0.3 – 300 nM) on this nAChR-mediated release were examined (Fig. 2A). α-CtxMII was superfused onto synaptosomes for 5 min prior to stimulation by ACh and was also present during stimulation. An α-CtxMII concentration-dependent inhibition of maximal [3H]-GABA release was observed. The α-CtxMII sensitive fraction represented 58 ± 7% of total release and maximal inhibition was achieved at 30nM α-CtxMII with an IC50 value of 1.05 nM ± 0.30.

Figure 2. Inhibition by α-conotoxins of [3H]-GABA release evoked by ACh from SuSC.

Crude synaptosomal preparations from the SuSC were loaded with [3H]-GABA, superfused for five minutes in the presence of varying concentrations of α-CtxMII (0.3-300nM) or α-CtxPIA (0.1-100nM) just prior to stimulating release of [3H]-GABA with 100μM ACh is shown in Panel 2A (n = 3-10 for each point on the graph; points represent mean ± S.E.M). The curve for inhibition by α-CtxMII represents the best fit of the data as one saturable component with a residual non-inhibitable component as described in the Methods. Since the inhibition by α-CtxPIA could not be reliably fit to an inhibition model, the lines merely connect the points. Panel 2B shows ACh concentration-response characterization of α-CtxMII-sensitive and -resistant ACh-evoked [3H]-GABA release from SuSC crude synaptosomes. Varying concentrations of ACh (0.1-100μM) were used to evoke [3H]-GABA release with (filled circles) and without (open circles) the presence of 100nM α-CtxMII to establish a release profile for the total and α-CtxMII-resistant components of the nAChR population in the SuSC. α-CtxMII-sensitive release (filled triangles) of [3H]-GABA was calculated by subtracting the resistant fraction from the total (n = 5 for each point; points represent mean values ± S.E.M). The curve describing the total release represents the best fit for a two-component process and the curves for the α-CtxMII-sensitive and –resistant components are the best fits for a one-component process as described in the Methods.

α-CtxMII inhibits both α3β2*- and α6β2*-nAChR (Azam & McIntosh 2005). In order to examine further the relative contribution of these two subtypes to ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release from SuSC, the effect of α-CtxPIA, which is a selective inhibitor of α6β2*-nAChR(Azam & McIntosh 2005), was tested (Fig 2A). These results were subsequently analyzed with a one-way ANOVA to test whether α-CtxPIA inhibited the release at any toxin concentration. This analysis indicated no significant inhibition by α-CtxPIA with in the concentration range used (One-way ANOVA, F(7,66)=0.68;p>0.05). As a control experiment, the relative inhibition of ACh-stimulated [3H]-dopamine release for crude striatal synaptosomes by α-CtxMII and α-CtxPIA was evaluated by the methods of (Salminen et al. 2007). ACh-stimulated [3H]-dopamine release was partially inhibited by treatment with 100 nM of either toxin (41.2 ± 2.8 % by α-CtxMII and 24.2 ± 3.3 % by α-CtxPIA; data not shown), confirming the activity of both toxins in a system known to include α6β2*-nAChR subtypes (Champtiaux et al. 2003).

The ACh sensitivity of the α-CtxMII-sensitive and resistant nAChR subtypes mediating [3H]GABA release

Inasmuch as ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release exhibited both an α-CtxMII-sensitive and an α-CtxMII-resistant component, concentration-response curves for ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release from SuSC crude synaptosomes were established with and without 100 nM α-CtxMII pretreatment to generate values for the activity of total ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release and α-CtxMII-resistant [3H]-GABA release (Figure 2B). Subtracting the release in the presence of α-CtxMII from the release in its absence at each ACh concentration, reveals the α-CtxMII-sensitive release fraction. The concentration-effect curve for total ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release from crude SuSC synaptosomes was biphasic with estimated EC50 values of 0.48 ± 0.33 μM and 33 ± 22 μM and maximal release of 0.68 ± 0.19 and 1.47 ± 0.21 for the high sensitivity and low sensitivity components, respectively. Subsequently the α-CtxMII-sensitive and –resistant components were calculated separately. The α-CtxMII-sensitive component has a lower EC50 (0.76 ± 0.47 μM, n = 5) for agonist than the α-CtxMII-resistant fraction (10.7 ± 7.3 μM, n = 5). The maximal ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release values were estimated to be 0.71 ± 0.08 and 1.00 ± 0.20 × baseline for the α-CtxMII-sensitive and α-CtxMII-resistant components, respectively.

Calcium Dependence of, Crude SuSC Synaptosomal [3H]-GABA Release

The release process was highly calcium dependent. For release evoked by 100μM ACh, 94 ± 3 % is lost in the absence of external calcium (data not shown). This suggests that ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release is largely or entirely mediated by a Ca2+-dependent synaptic vesicle fusion mechanism. ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release was also blocked by 200 μM cadmium (94 ± 1 %), confirming the requirement for activation of calcium channels to elicit release (data not shown).

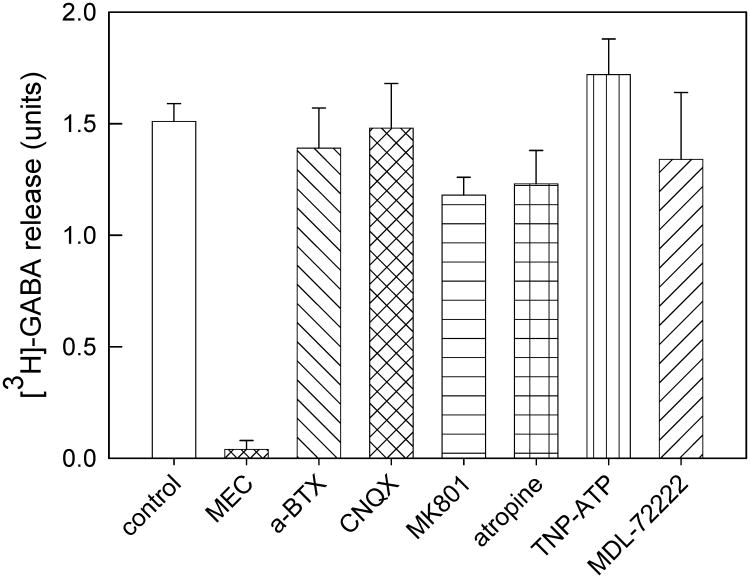

Effects of Additional Nicotinic Receptor Antagonists and Effects of non-nicotinic antagonists on ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA Release

[3H]-GABA-loaded crude synaptosomes were exposed to various antagonists prior to stimulation by 100 μM ACh; antagonists were present in the stimulation buffer as well as in pretreatment (Fig. 3). Mecamylamine exposure (10 μM, 1 min) completely eliminated ACh-stimulated release of [3H]-GABA, indicating that this release is entirely nAChR-dependent under the experimental conditions used in this study. α-bungarotoxin (α-Bgt, 1 μM, 10 min) had no effect on ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release (p=0.70, Student's t-test) demonstrating that α7 nAChR are not involved. The antagonists MK-801, CNQX, MDL-72222, TNP-ATP and atropine that inhibit NMDA, AMPA, 5-HT3, P2X, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors, respectively, were present for 4-5 min prior to stimulation by 100 μM ACh. The antagonists were present in the agonist solution as well as during pretreatment. There was no effect of any of these non-nAChR antagonists on ACh-stimulated release of [3H]-GABA (Fig. 4). These results support the assertion that the observed nAChR-mediated [3H]-GABA release was mediated by direct activation of nAChRs on SuSC GABAergic terminals.

Figure 3. Effects of antagonists on [3H]-GABA release evoked by ACh from SuSC.

Crude synaptosomes prepared from the SuSC were loaded with [3H]-GABA, and, prior to stimulation with 100μM ACh, superfused with mecamylamine (10 μM for 1 min, n=3), α-Bgt (1 μM, 10 min, n=4), CNQX (100 μM, 5 min (n=4), MK801 (200 μM, 5 min, n=4), atropine (1 μM, 5 min, n=8), TNP-ATP (10 μM, 4 min, n=3), or MDL-72222 (1 μM, 5 min, n=5). Histogram bars represent mean values ± S.E.M.

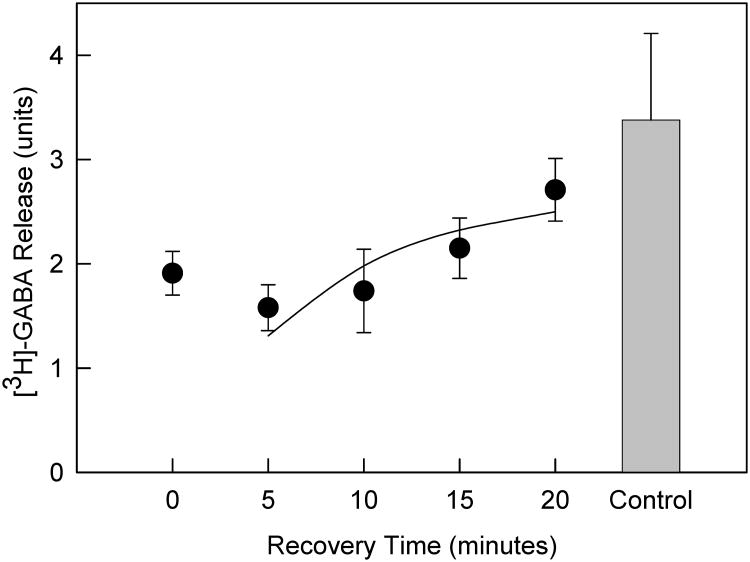

Figure 4. Recovery of α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR-mediated [3H]-GABA release from SuSC.

Crude synaptosomes were prepared from SuSC, loaded with [3H]-GABA and superfused with 100nM α-CtxMII for five minutes, then subjected to varying times of α-CtxMII-free buffer washout prior to stimulation by 100μM ACh to measure the total release of [3H]-GABA elicited by ACh (n = 3-4) for each point. Points represent mean values ± S.E.M. The curve represents a single exponential recovery of activity beginning 5 min after removal of α-CtxMII.

Recovery of ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release from α-CtxMII Inhibition

The recovery rate of SuSC synaptosomes from α-CtxMII inhibition was examined. [3H]-GABA-loaded SuSC crude synaptosomes were prepared for release experiments as previously described, and pretreated with α-CtxMII (100 μM, 5 min). Following a variable wash period in toxin-free buffer (5, 10, 15, 20 min), release was evoked with 100μM ACh (Fig. 4). Following a lag period of approximately 5 min during which no recovery was observed, functional recovery to 91 ± 18% of control occurred after 20 min of washout, with a t1/2 for recovery of 5.2 min observed. To control for non-nAChR-specific effects of α-CtxMII, the effects of α-CtxMII (100 nM) pretreatment on K+ (20 mM)-evoked [3H]-GABA release from SuSC synaptosomes were also tested. Release induced by 20 mM K+ was indistinguishable in the presence (14.1 ± 2.7) and absence of α-CtxMII (14.0 ± 1.7) (n = 5, data not shown).

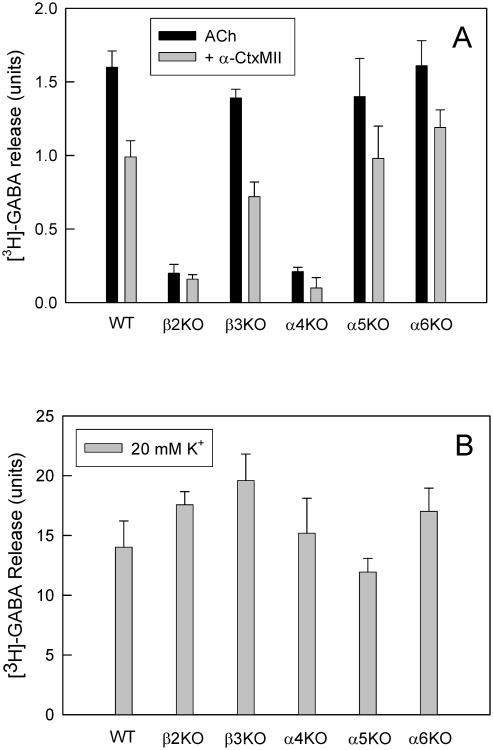

Studies using nAChR subunit null mutant mice

In order to augment the pharmacological characterization of the nAChRs mediating SuSC synaptosomal [3H]-GABA release, nAChR subunit null-mutant mice were examined as an additional method to determine subunit composition. Crude synaptosomes were prepared from the SuSC of homozygous β2-, α4-, β3-, α5- and α6-null mutant mice, and were loaded with [3H]-GABA. These samples were pretreated with either standard perfusion buffer without or with α-Ctx-MII (100 nM) for 5 min, prior to stimulation with 100 μM ACh.

As shown in Fig. 5A, ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release is completely absent from β2-/- SuSC mouse crude synaptosomes as is, by definition, any effect of α-CtxMII. ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release in the SuSC is greatly reduced, but not abolished in α4-/- mice (9.7 ± 1.1% of WT activity remaining; Fig. 5A). Importantly, the remaining function in α4-null samples is almost abolished by α-CtxMII (100 nM; Student's t-test; p<0.05; n = 6). In contrast to the dramatic effects of α4 and β2 nAChR subunit deletion, deletion of β3 subunit expression had no effect on either α-CtxMII-sensitive or –resistant ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release from SuSC synaptosomes (Fig.5A; Student's t-test p<0.05; n = 4). This lack of β3-null effect is very different to the significant effects of β3 subunit deletion on dopaminergic pathway α6* nAChR expression (Salminen et al. 2007). Finally, SuSC synaptosomal [3H]-GABA release in α6-null mutant mice, in both the presence and absence of α-CtxMII, was indistinguishable from the same measures in wild-type mice (Fig.5A; Student's t-test, p<0.05; n = 4). However, deletion of the α6 gene eliminated most of the α-CtxMII-sensitive [125I]-epibatidine binding sites (data not shown), confirming the presence of α6β2*-nAChR in SuSC (Gotti et al. 2005b) that, however, do not play a significant role in SuSC nAChR-mediated [3H]-GABA release. α3-null mutant mice would be a useful addition to this panel of nAChR subunit-null mutants, however, they were not available, as loss of the α3 subunit is neonatally lethal (Xu et al. 1999).

Figure 5. The subunit composition nAChRs mediating ACh-evoked [3H]-GABA release from SuSC.

Crude synaptosomes were prepared from the SuSC of mice lacking one nAChR subunit (n=6-8 mice per genotype), as indicated, loaded with [3H]-GABA, and then superfused with or without 100nM α-CtxMII for five minutes prior to stimulation with 100μM ACh (Panel 5A). Bars represent mean values ± S.E.M. Panel 5B shows similar data for stimulation with 20 mM K+ (n=3-7 mice per genotype)

In order to evaluate whether nAChR gene deletion affected the general responsiveness of the crude synaptosomal preparations, 20 mM K+-stimulated [3H]-GABA release was measured as a further control. No significant effects of nAChR gene deletion on this measure were observed (Fig 5B).

Discussion

In this study, the existence and properties of a SuSC α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR population were investigated using neurochemical and nAChR null-mutant approaches. The major finding of this study is that a novel, α-CtxMII-sensitive, α3α4β2 nAChR population modulates release from GABAergic nerve terminals in the SuSC. This conclusion supports and expands on previous work that identified α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR responses in local GABAergic interneurons of the SuSC, and demonstrated that activation of presynaptic α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs on these interneurons elicited bursts of mini-IPSCs on neighboring, non-GABAergic SuSC neurons (Endo et al. 2005). However, the subunit composition of this nAChR population was not definitively established. Collectively, our findings reveal a new level of modulation of neurotransmitter release by SuSC GABAergic interneurons, mediated by presynaptic, α3α4β2-subtype, α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs. This newly characterized nAChR subtype is distinctly different from the extensively-studied α6*-containing α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR subtypes expressed on VTA/SN dopamine neuron terminals.

High-affinity [125I]-epibatidine binding in membranes prepared from isolated SuSC and SC core tissue of C57BL/6 mice demonstrated the presence of α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs in the SuSC only. This finding is consistent with the initial report of [125I]-α-CtxMII binding in the superior colliculus (Whiteaker et al. 2000b), and suggested that functional SuSC nAChRs might also be divided into two subpopulations (α-CtxMII-sensitive and –resistant). Previous findings (see Introduction) indicated that one or both of these nAChR populations would be capable of eliciting [3H]-GABA release from crude SuSC synaptosomal preparations.

Measurement of [3H]-GABA release from crude SuSC synaptosomes revealed that ACh was capable of directly eliciting the release of GABA via activation of presynaptic nAChRs. Exposure to 100nM α-CtxMII reduced the response seen by stimulation with ACh, but did not eliminate it. Examining the α-CtxMII-sensitive and resistant components shows that the α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR subtype has a higher affinity for ACh than does the resistant nAChR subtype. This result is consistent with previously characterized α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs found on DAergic terminals in the striatum of mice and rats (Kulak et al. 1997, Kaiser et al. 1998, Grady et al. 2002). Interestingly, the relatively-high EC50 for ACh release at the α-CtxMII-resistant (α4β2*) nAChR population indicates a significant portion of low-sensitivity (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs is present on crude SuSC synaptosomes (Marks et al. 1999).

Further investigation showed that the α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR population located on SuSC GABA-terminals differs extensively from its DA-terminal counterpart. The measured recovery from inhibition by α-CtxMII in the SuSC is much more rapid (t1/2 ∼5 min) than that observed with [3H]-DA release in the striatum (t1/2 ∼26 min) (Salminen et al. 2004). This suggested a possible α3β2* composition of the crude SuSC synaptosomal α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR population, since function of rat α6/3β2 chimeric nAChRs expressed in oocytes exhibited very slow recovery from α-CtxMII inhibition (t1/2 > 20 minutes whereas the t1/2 for rat α3β2 receptors occurred was approximately 4 minutes and full recovery was observed by 26 min (McIntosh et al. 2004) (Cartier et al., 1996).

The α6*-selective conotoxin α-CtxPIA (Azam & McIntosh 2005) was used in order to more-definitively identify the nAChR subtype that modulates α-CtxMII-sensitive [3H]-GABA release in the SuSC. In crude rat striatal synaptosomal preparations expressing α6* nAChRs, α-CtxPIA acts as a potent (IC50 = 1.48nM), slowly reversible inhibitor of DA release stimulated by nicotine or ACh (Azam & McIntosh 2005). In crude preparations of SuSC synaptosomes, even 100nM α-CtxPIA was completely unable to inhibit ACh-stimulated [3H]-GABA release. This finding further suggests that functional expression of the α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR responsible for eliciting GABA release in the region is dependent on the expression of α3, rather than α6, subunits.

In common with previously-characterized native α6β2* nAChRs, nAChR-mediated SuSC crude synaptosomal [3H]-GABA release is completely β2 subunit dependent. However, the novel composition of the SuSC α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR population is further established by evidence from subunit-null mutant mouse experiments. For example, appropriate functional assembly appears to be largely (>90 %) α4 dependent. This dependence is much higher than that (∼50 %) measured for the α-CtxMII-sensitive nigrostriatal α6* nAChRs that mediate [3H]-DA release (Gotti et al. 2005a, Salminen et al. 2005, Salminen et al. 2004). In addition, α-CtxMII sensitive SuSC crude synaptosomal [3H]-GABA release is unaffected by β3 subunit gene deletion in agreement with a previous report indicating that α3* nAChR expression is not affected by nAChR β3 subunit deletion in the SuSC (Gotti et al, 2005). This contrasts with evidence that β3 subunit deletion reduces α6* nAChR functional expression by ≈75 % (Salminen et al. 2004). Finally, deletion of the α6 subunit by gene null mutation also has no appreciable impact on α-CtxMII-sensitive [3H]-GABA release from crude SuSC synaptosomal preparations. This is arguably the most convincing evidence that the α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR populations mediating SuSC [3H]-GABA release and striatal [3H]-DA release differ in their subunit compositions. This lack of effect of nAChR α6 subunit gene deletion is consistent with the failure of the α6 selective toxin α-CtxPIA to inhibit collicular nAChR mediated [3H]-GABA release. The preceding experimental outcomes combine to demonstrate that an α3α4β2 nAChR mediates α-CtxMII sensitive ACh-evoked [3H]-GABA release in the superficial superior colliculus. This stands in strong contract to the situation in most other brain regions, where nAChR modulation of GABA release is mediated by α4β2* nAChRs (Lu et al. 1998). In the one other exception observed to date, α6β2* nAChRs have been shown to modulate presynaptic GABA release onto VTA dopamine neurons (Yang et al. 2011). These recent findings, along with those of the current study, indicate that specific subtypes of α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs may have previously unappreciated functional roles in select brain regions. The existence of α3β2* nAChRs with potentially important physiological roles may offer opportunities for novel drug design. Conversely, it may prove important to avoid interactions with α3β2* nAChRs while developing therapies targeting the closely-related α6β2* subtypes that are also α-CtxMII sensitive (Breining et al. 2009, Grady et al. 2010).

In summary, we provide evidence that in the mouse SuSC, a novel presynaptic α3α4β2 subtype nAChR that is sensitive to α-CtxMII is capable of eliciting the release of [3H]-GABA. Approximately 35% of this exocytotic release process is due to the activation of this novel receptor, while the more ubiquitously expressed α4β2*-type receptor is responsible for the remaining 65% of [3H]-GABA release elicited by exposure to ACh.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from NIH grants DA012242 (to PW), MH53631 and GM48677 (to JMM), and DA015663 and DA003194 (to MJM).

Abbreviations

- α-Bgt

α-bungarotoxin

- α-Ctx

α-conotoxin

- CNQX

6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- DA

dopamine

- GAT-1

GABA transporter 1

- MDL-72222

Tropanyl 3,5-dichlorobenzoate

- MK-801

(5S,10R)-(+)-5-Methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NNC-711

1,2,5,6-Tetrahydro-1-[2[(diphenylmethylene)amino]oxy]ethyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid

- SN

substantia nigra

- SuSC

superficial layers of the superior colliculus

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

References

- Azam L, Dowell C, Watkins M, Stitzel JA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. α-Conotoxin BuIA, a Novel Peptide from Conus bullatus, Distinguishes among Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:80–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, McIntosh JM. Effect of novel alpha-conotoxins on nicotine-stimulated [H-3]dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2005;312:231–237. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns KE, Turner JP, Salt TE. Visual experience alters the molecular profile of NMDA-receptor-mediated sensory transmission. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:1101–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breining SR, Bencherif M, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Wageman CR, Lester HA, Yohannes D. Evaluation of structurally diverse neuronal nicotinic receptor ligands for selectivity at the α6∗ subtype. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2009;19:4359–4363. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier GE, Yoshikami DJ, Gray WR, Luo SQ, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. A new alpha-conotoxin which targets alpha 3 beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:7522–7528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, et al. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:7820–7829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PBS, Schwartz RD, Paul SM, Pert CB, Pert A. Nicotinic Binding in Rat-Brain - Autoradiographic Comparison of [H-3] Acetylcholine, [H-3] Nicotine, and [I-125] Alpha-Bungarotoxin. Journal of Neuroscience. 1985;5:1307–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01307.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BC, Marritt AM, Perry DC, Kellar KJ. Transport of multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat optic nerve: high densities of receptors containing α6 and β3 subunits. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1924–1938. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui CH, Booker TK, Allen RS, et al. The beta 3 nicotinic receptor subunit: A component of alpha-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate dopamine release and related behaviors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:11045–11053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Isa T. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes involved in facilitation of GABAergic inhibition in mouse superficial superior colliculus. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005;94:3893–3902. doi: 10.1152/jn.00211.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, Rogers SW, Pabreza LA, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. A Subtype of Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptor in Rat-Brain Is Composed of Alpha-4-Subunit and Beta-2-Subunit and Is up-Regulated by Chronic Nicotine Treatment. Molecular pharmacology. 1992;41:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, et al. Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochemical pharmacology. 2009;78:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Clementi F, Riganti L, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Whiteaker P. Expression of nigrostriatal alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is selectively reduced, but not eliminated, by beta 3 subunit gene deletion. Molecular pharmacology. 2005a;67:2007–2015. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Zanardi A, et al. Heterogeneity and Selective Targeting of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (nAChR) Subtypes Expressed on Retinal Afferents of the Superior Colliculus and Lateral Geniculate Nucleus: Identification of a New Native nAChR Subtype α3β2(α5 or β3) Enriched in Retinocollicular Afferents. Molecular pharmacology. 2005b;68:1162–1171. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Drenan RM, Breining SR, et al. Structural differences determine the relative selectivity of nicotinic compounds for native α4β2*-, α6β2*-, α3β4*- and α7-nicotine acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Murphy KL, Cao J, Marks MJ, McIntosh JM, Collins AC. Characterization of nicotinic agonist-induced [H-3] dopamine release from synaptosomes prepared from four mouse brain regions. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;301:651–660. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser SA, Soliakov L, Harvey SC, Luetje CW, Wonnacott S. Differential inhibition by alpha-conotoxin-MII of the nicotinic stimulation of [H-3]dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes and slices. Journal of neurochemistry. 1998;70:1069–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70031069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulak JM, Nguyen TA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. alpha-Conotoxin MII blocks nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in rat striatal synaptosomes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:5263–5270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05263.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, Schmidt M, Hall WC. Excitatory and inhibitory circuitry in the superficial gray layer of the superior colliculus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:8145–8153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08145.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein Measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Grady S, Marks MJ, Picciotto M, Changeux JP, Collins AC. Pharmacological characterization of nicotinic receptor-stimulated GABA release from mouse brain synaptosomes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;287:648–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ, Changeux JP, Le Novere N, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XX. Current status of the nomenclature for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their subunits. Pharmacological Reviews. 1999;51:397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Whiteaker P, Calcaterra J, Stitzel JA, Bullock AE, Grady SR, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP, Collins AC. Two pharmacologically distinct components of nicotinic receptor-mediated rubidium efflux in mouse brain require the beta 2 subunit. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;289:1090–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Gardier AM, Durier S, et al. Effects of nicotine in the dopaminergic system of mice lacking the alpha4 subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;17:1329–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure-Begley TD, King NM, Collins AC, Stitzel JA, Wehner JM, Butt CM. Acetylcholine-Stimulated [3H]GABA Release from Mouse Brain Synaptosomes is Modulated by α4β2 and α4α5β2 Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes. Molecular pharmacology. 2009;75:918–926. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JM, Azam L, Staheli S, Dowell C, Lindstrom JM, Kuryatov A, Garrett JE, Marks MJ, Whiteaker P. Analogs of alpha-conotoxin MII are selective for alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Molecular pharmacology. 2004;65:944–952. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly JR, Stitzel JA, Marks MJ, Collins AC. An Autoradiographic Analysis of Cholinergic Receptors in Mouse-Brain. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:453–459. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Drapeau JA, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. Molecular pharmacology. 2007;71:1563–1571. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Grady SR. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Molecular pharmacology. 2004;65:1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Whiteaker P, Grady SR, Collins AC, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ. The subunit composition and pharmacology of alpha-Conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors studied by a novel membrane-binding assay. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer R, Conroy WG, Whiting P, Gore M, Lindstrom J. Brain Alpha-Bungarotoxin Binding-Protein Cdnas and Mabs Reveal Subtypes of This Branch of the Ligand-Gated Ion Channel Gene Superfamily. Neuron. 1990;5:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90031-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunekawa N, Yanagawa Y, Obata K. Development of GABAergic neurons from the ventricular zone in the superior colliculus of the mouse. Neurosci Res. 2005;51:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteaker P, Jimenez M, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ. Identification of a novel nicotinic binding site in mouse brain using [I-125]-epibatidine. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000a;131:729–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Luo SQ, Collins AC, Marks MJ. I-125-alpha-conotoxin MII identifies a novel nicotinic acetylcholine receptor population in mouse brain. Molecular pharmacology. 2000b;57:913–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P, Lindstrom J. Purification and Characterization of a Nicotinic Acetylcholine-Receptor from Rat-Brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:595–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Gelber S, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. Megacystis, mydriasis, and ion channel defect in mice lacking the alpha 3 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:5746–5751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Buhlman L, Khan GM, Nichols RA, Jin G, McIntosh JM, Whiteaker P, Lukas RJ, Wu J. Functional Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Containing {alpha}6 Subunits Are on GABAergic Neuronal Boutons Adherent to Ventral Tegmental Area Dopamine Neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2537–2548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3003-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Moretti M, Zanardi A, McIntosh JM, Clementi F, Gotti C. Identification of the nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:8785–8789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]