Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess long-term safety and tolerability of desvenlafaxine (administered as desvenlafaxine succinate) in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods: An 8 week, multicenter, open-label, fixed-dose study of children (ages 7–11 years) and adolescents (ages 12–17 years) with MDD was followed by a 6 month, flexible-dose extension study. Patients were administered desvenlafaxine 10–100 mg/day (children) or 25–200 mg/day (adolescents) for a total of 8 months. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), withdrawals because of AEs, laboratory tests, vital signs, and the Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) were collected. Eight month safety results from the lead-in plus extension studies are reported for extension study participants, using lead-in study day −1 as baseline.

Results: Forty patients were enrolled in both studies (20 children; 20 adolescents). Of those, four children and three adolescents withdrew because of AEs. Treatment-emergent AEs reported by three or more patients were upper abdominal pain (15%) and headache (15%) in children, and somnolence (30%), nausea (20%), upper abdominal pain (15%), and headache (15%) in adolescents. Negativism (oppositional behavior) in a child was the single serious AE reported. No deaths occurred during the lead-in or extension studies. Mean pulse rates demonstrated statistically significant increases from lead-in study baseline to final evaluation (children, +5.2 bpm; adolescents, +5.9 bpm; p≤0.05). No statistically significant change in blood pressure was observed at final evaluation. Two adolescents (0 children) reported suicidal ideation on the C-SSRS at screening assessment and during the lead-in and/or extension trials; one adolescent reported suicidal ideation after screening only.

Conclusions: Long-term (8 month) treatment with desvenlafaxine was generally safe and well tolerated in depressed children and adolescents.

Introduction

An estimated 1–6% of children and adolescents have major depressive disorder (MDD), with lifetime prevalence estimates ranging from 4–25% (Kessler et al. 2001). Reported prevalence rates range from 0.4–2.5% in children and from 0.4–8.3% in adolescents, with an increasing risk of depression after puberty, particularly in girls (Birmaher et al. 1996, 2007). For children and adolescents with moderate to severe depression, antidepressant therapy is recommended (Birmaher et al. 2007; Cheung et al. 2007; American Academy of Pediatrics 2009; Chua et al. 2012). Treatment guidelines recommend acute- and continuation-phase treatment (6–12 months) for children and adolescents with MDD, and maintenance treatment lasting ≥1 year may be recommended for patients with severe, recurrent, and chronic symptoms (Birmaher et al. 2007; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2009). Rates of antidepressant prescribing, however, have declined in the United States (Nemeroff et al. 2007; Libby et al. 2009) and the United Kingdom (Murray et al. 2005), since a warning for suicidal ideation and behavior was added to antidepressant labeling based on a signal of increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in pediatric patients (Laughren 2006). In a retrospective insurance claims database analysis designed to assess cost of delaying pharmacotherapy in 7344 adolescents diagnosed with depression, a 1–12 month delay in the first prescription of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) was associated with significantly higher medical costs and an increased risk of depression-related emergency department visits compared with patients who started pharmacotherapy within 1 month of diagnosis (Yu et al. 2011).

The SNRI desvenlafaxine (administered as desvenlafaxine succinate) is approved in the United States and >30 other countries for the treatment of MDD in adults (Pristiq® package insert 2011). Efficacy of desvenlafaxine has been demonstrated in adult patients at the recommended therapeutic dose of 50 mg/day (Boyer et al. 2008; Liebowitz et al. 2008; Rosenthal et al. 2013). The efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine at doses ranging from 10 mg/day to 400 mg/day have been assessed in adults with MDD. In integrated analyses of pooled data from adult, fixed-dose studies of desvenlafaxine for MDD, rates of adverse events (AEs) and discontinuations caused by AEs increased with increasing desvenlafaxine dose, and no additional efficacy benefit was observed at doses above the lowest effective dose of 50 mg/day (Clayton et al. 2009; Thase et al. 2009).

Desvenlafaxine has not been approved for pediatric use. A pediatric program evaluating desvenlafaxine in the treatment of MDD in children (ages 7–11 years) and adolescents (ages 12–17 years) has been undertaken. Prior to initiation of definitive efficacy studies of antidepressants in children and adolescents with MDD, pharmacokinetic and dose-ranging safety studies are needed in order to avoid the failure of efficacy studies caused by improper dosing regimens (Findling et al. 2006). Accordingly, an 8 week, open-label, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic study of single ascending doses of desvenlafaxine in children and adolescent outpatients with MDD was conducted. A 6 month safety and tolerability extension study enrolled pediatric patients who had completed the preceding 8 week trial. The primary objective of the two studies was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of desvenlafaxine in children and adolescents with MDD. The study protocols included a secondary objective to assess the efficacy of desvenlafaxine in children and adolescents with MDD in an exploratory manner. This article reports the full 8 month safety and efficacy data from the lead-in plus extension studies for all patients who were enrolled in the extension study.

Methods

The 8 week, open-label, fixed-dose, lead-in study and 6 month, open-label, flexible-dose extension study of desvenlafaxine safety and tolerability were conducted at a total of seven sites in the United States between February 2008 and May 2010. The studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (European Medicines Agency 2002) and the ethical principles that have their origins in the Declaration of Helsinki (National Institutes of Health 2004). The protocol and amendments received institutional review board or independent ethics committee approval. Parents provided written informed consent, and patients provided witnessed written assent before any procedures outlined in the protocol were performed.

Patients

Patients enrolled in the lead-in study were male and female outpatients, ages 7–11 years (children) or 12–17 years (adolescents) at baseline. Entry criteria for the lead-in study included a diagnosis of depression of at least moderate severity meeting criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision for MDD (with symptoms for at least 1 month before screening)(American Psychiatric Association 2000), screening and baseline Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (Poznanski et al. 1979) (CDRS-R) score>40, and Clinical Global Impressions–Severity of Illness Scale (CGI-S) (Guy 1976) score of at least 4. Lead-in study exclusion criteria established a study population of medically healthy patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis of MDD. Patients were also excluded if they had a history of suicide attempt or evidence of current suicidal ideation or behavior based on CDRS-R and 17 item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) (Hamilton 1960) suicide items or Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al. 2011) responses. Children and adolescents with MDD who had completed 8 weeks of treatment in the lead-in study and who, in the opinion of the investigator, would benefit from long-term treatment, were enrolled in the 6 month extension. Patients who completed the lead-in study were excluded from the extension trial if they had clinically important abnormalities on physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), laboratory, or vital signs results at, or prior to, the extension study baseline visit. Patients were required to agree and commit to the use of a reliable method of birth control throughout the studies. Per protocol, pregnancy was considered a reportable AE; any patient reporting pregnancy was immediately discontinued from the study drug.

Study design

Lead-in study

The short-term lead-in study included an initial 4 day inpatient period designed to characterize the 72 hour desvenlafaxine pharmacokinetic profile, followed by a 7.5 week outpatient period evaluating safety, tolerability, and exploratory efficacy. Patients in each age stratum were assigned to 1 of 4 desvenlafaxine doses selected for characterizing the pharmacokinetic profile. (Pharmacokinetic data are not included in this report, and will be reported elsewhere.) Children were assigned to desvenlafaxine 10, 25, 50, or 100 mg/day, and adolescents to desvenlafaxine 25, 50, 100, or 200 mg/day. On day 1 of the inpatient period, patients received a single desvenlafaxine dose according to their dose assignment. No desvenlafaxine was administered on study days 2 and 3. During the outpatient period, patients were administered the same fixed dose of desvenlafaxine that they had received on study day 1, except during a 0–12 day titration period (depending upon dose), which started on study day 4. The 10, 25, and 50 mg dose groups were administered 10 mg/day starting day 4, and the 25 and 50 mg groups had their dose increased to 25 mg/day starting day 8; the 50 mg group received the assigned dose on day 15. The titration schedule for the 100 mg group was 25 mg/day on days 4 to 7, 50 mg/day on days 8–14, and 100 mg/day starting on day 15; the schedule for the 200 mg group was 50 mg/day on days 4–7, 100 mg/day on days 8–14, and 200 mg/day starting on day 15.

Extension study

The extension study was a flexible-dose trial; children received desvenlafaxine 10–100 mg/day, and adolescents received desvenlafaxine 25–200 mg/d for up to 6 months. Beginning at day 56 of the lead-in study (extension study baseline visit), patients were either given the same daily dose to which they were assigned in the lead-in study, or an adjusted dose as clinically indicated, in order to maximize clinical benefit while minimizing AEs. Dosage was adjusted by the investigator at each study visit, as clinically indicated. The open-label treatment period was followed by a 0–2 week taper period, depending upon dose at discontinuation (10 mg/day, no taper; 25 mg/day, 7-day taper; ≥50 mg/day, 14-day taper). A follow-up evaluation was scheduled 7 days after the last tapered dose or last dose of the study drug, if the taper had been omitted.

Safety and efficacy data from the lead-in study are reported together with extension trial data for all patients who completed the lead-in and enrolled in the extension study. Baseline values from the lead-in study (lead-in study day −1) were used as the baseline for all efficacy and safety end-points reported.

Safety and tolerability

Safety assessments included vital sign measurements (supine and standing blood pressure [BP], pulse rate, body weight, and height), 12-lead ECGs, clinical laboratory determinations, physical examination, and C-SSRS. Vital signs were measured at lead-in study baseline and days 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, and 56, and the C-SSRS was administered at lead-in study baseline and days 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, and 56 of the open-label lead-in study; both were collected during extension study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, and 26. Laboratory determinations were performed at lead-in study baseline, lead-in study days 28 and 56 (final visit), and extension study weeks 14, 18, and 26; ECG recordings were made at lead-in study baseline and day 56 (final visit), and extension study weeks 4, 10, 14, 18, and 26. A comprehensive physical examination (including Tanner assessment) was scheduled at lead-in study baseline and day 56 (final visit) and extension study week 26. In the event of early withdrawal from the extension study, week 26 assessments were completed at withdrawal. Adverse events (categorized based on Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities [MedDRA] terminology) and withdrawals caused by AEs were monitored throughout both studies.

Efficacy assessments

All efficacy assessments were exploratory, because of the lack of a placebo control. The primary efficacy outcome was CDRS-R total score. Secondary efficacy outcomes were HAM-D17 total score, CGI-S score, Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement Scale (CGI-I) score and responder rate (based on a CGI-I score of 1 or 2), and CDRS-R remission rate (CDRS-R total score ≤28). The CDRS-R, CGI-S, and CGI-I were administered at lead-in study baseline (except CGI-I) and days 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, and 56; HAM-D17 was administered at lead-in study baseline and days 4, 14, 28 and 56. All efficacy assessments were administered at extension study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, and 26 or at early withdrawal.

Statistical analyses

The sample size for the lead-in study was not based on statistical power considerations; the statistical analyses were descriptive in nature. The target enrollment was at least 24 patients per age stratum (6 per dose group), as administration of desvenlafaxine to at least 6 subjects in each dose group provided a 47%, 62%, 74%, or 82% probability of observing at least one occurrence of any AE with a true AE incidence rate given for a dose group of 10%, 15%, 20%, or 25%, respectively. Sample size for the extension study was based on all available patients who completed the lead-in study and subsequently entered the extension study.

The safety population included all patients who took at least 1 dose of the study drug during the 6 month extension. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and taper/poststudy-emergent AEs were tabulated by age stratum. Vital sign measurements, Tanner assessment scores, laboratory evaluations, ECGs, and C-SSRS data were summarized by age stratum using descriptive statistics; no formal statistical comparisons were performed. The numbers of patients with safety results of potential clinical importance—categorical changes in laboratory findings, vital signs, ECG results defined according to age- and sex-specific criteria prespecified by the sponsor, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or the European Medicines Agency (EMA)—were tabulated. Clinically important results were identified by the medical monitor based on a review of patient data, relevant clinical information pertaining to a patient, and clinical judgment. Systolic blood pressure changes were considered clinically important based on elevations in systolic blood pressure readings above the prespecified potentially clinically important criteria for three consecutive visits during the course of the study.

The primary population for efficacy analyses was the intent-to-treat population, defined as all patients who took at least 1 dose of the study drug, and had baseline and at least one postbaseline efficacy evaluation during the extension study. For continuous efficacy variables, mean change from lead-in study baseline (study day −1) was summarized at each time point by age stratum and overall, using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach for handling missing data. For categorical efficacy variables, the proportions of patients in each category were summarized by age stratum and overall, at lead-in week 8 and at extension week 26 (LOCF).

Results

Patients

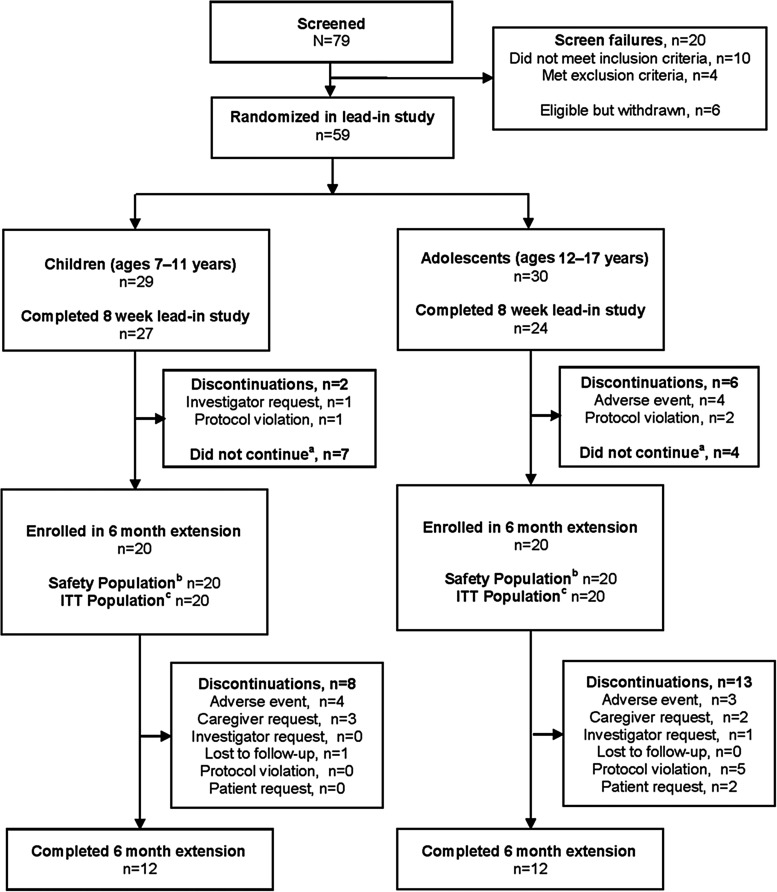

A total of 59 patients (29 children, 30 adolescents) were assigned to treatment in the 8 week lead-in study; 8/59 patients withdrew early and 51 patients completed the lead-in study (Fig. 1). Of the 51 patients completing the lead-in study, a total of 40 (20 children, 20 adolescents) were enrolled in the 6 month extension. Data presented herein are based on those 40 patients who were enrolled in both studies. All 40 patients took at least 1 dose of the study medication in the extension study and were included in the safety population. Demographic and baseline characteristics for the safety population are listed in Table 1. Baseline values are from the lead-in study baseline (lead-in study day −1).

FIG. 1.

Study flow. ITT=intent to treat. aReasons for not continuing into the extension trial were not collected. bRandomly assigned to treatment and took ≥1 dose of study medication. cRandomly assigned to treatment, took ≥1 dose of study medication, and had baseline and ≥1 postbaseline primary efficacy evaluation.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristicsa: Safety Population

| Child (n=20) | Adolescent (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 9.7 (1.3) | 13.6 (1.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 11 (55) | 9 (45) |

| Male | 9 (45) | 11 (55) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | ||

| Black or African American | 10 (50) | 11 (55) |

| White | 10 (50) | 7 (35) |

| Other | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 142.3 (8.0) | 164.1 (9.0) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 40.0 (10.7) | 68.3 (22.0) |

| Duration of current episode, mean (SD), months | 8 (7) | 11 (11) |

| Baseline CGI-S score, mean (SD) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.3) |

| Moderately ill, n (%) | 19 (95) | 18 (90) |

| Markedly ill, n (%) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Baseline CDRS-R total score, mean (SD) | 52.0 (6.2) | 57.4 (9.3) |

At lead-in study day –1.

CDRS-R, Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions Scale–Severity of Illness.

Lead-in study desvenlafaxine dose assignments for the 40 patients who enrolled in the extension study were as follows: 10 mg/day, 4 children; 25 mg/day, 5 children and 1 adolescent; 50 mg/day, 8 children and 9 adolescents; 100 mg/day, 3 children and 6 adolescents; and 200 mg/day, 4 adolescents. Dosing during the 6 month extension was flexible. Two children had desvenlafaxine dose increases, 1 from 10 –25 mg/day and the other from 25–50 mg/day, both at extension study week 5. Four adolescents (all from the same study site) had their desvenlafaxine dose increased from 25–50 mg/day at extension study week 2 or 3; of those, one had a second increase to 100 mg/day at extension study week 8. No patients had their dose decreased, except at taper. The mean daily desvenlafaxine dose at the end of the open-label treatment period (excluding taper) was 47.9 mg/day for children and 93.8 mg/day for adolescents. A total of 14 (70%) children and 10 (50%) adolescents had an exposure duration >28 weeks over the course of the acute plus extension studies.

Safety and tolerability

Of the 40 patients enrolled in the two studies, 8 of 20 (40%) children and 13 of 20 (65%) adolescents discontinued early during the 6 month extension. Reasons for discontinuation are reported in Figure 1. The most common reason for discontinuation from the extension study among children was AE, and among adolescents was protocol violation. Four (20%) children and three (15%) adolescents discontinued the extension study because of AEs. AEs cited as a reason for discontinuation by children were aggression (two children), disturbance in attention and psychomotor activity (one), and negativism (one). Four AEs were cited as reasons for discontinuation by the three adolescents: nausea (two), headache (one), and pregnancy (one). The discontinuation because of pregnancy occurred at extension study week 14; however, because confirmation of the pregnancy by a positive serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin test was received the day after the patient's last dose, it was recorded as a poststudy AE. The patient reported having used birth control; therefore, no protocol violation was recorded.

Thirteen (65%) children and 15 (75%) adolescents reported TEAEs over the course of the 8 week lead-in plus 6 month extension. The most commonly reported TEAEs (reported by three or more patients in either age group) during the 8 month treatment period were upper abdominal pain (three children, three adolescents), nausea (two children, four adolescents), headache (three children, three adolescents), and somnolence (one child, six adolescents). For the 40 patients enrolled in both studies, rates of TEAEs were 25% and 40% for children and adolescents, respectively, during the lead-in study inpatient period (days 1–4); 30% and 50%, respectively, during the lead-in study outpatient period (day 5 through week 8); and 45% and 40%, respectively, during the 6 month extension. TEAEs reported by three or more patients in either group during each period included the following: lead-in inpatient period, nausea (one child, three adolescents); lead-in study outpatient period, headache (three children, three adolescents), and somnolence (one child, four adolescents); and 6 month extension, none. Nausea was reported by one child and two adolescents during the lead-in study outpatient period and by one adolescent (0 children) during the extension study. Taper/poststudy-emergent AEs were reported by one child (headache) and two adolescents (pregnancy [described previously], depressive symptoms).

A single serious AE was reported for patients enrolled in the two studies. The AE was negativism (oppositional behavior), reported in a 9-year-old male child with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional behavior, who took desvenlafaxine 50 mg/day from day 14 of the preceding short-term study and continued into the extension study. It was reported that during extension study week 2, the child exhibited oppositional, disruptive, and aggressive behavior. The AE led to the patient's permanent withdrawal from the study. The patient was not hospitalized, but the AE was deemed medically important by the medical monitor. The AE persisted at the taper and follow-up visits. It was considered by the investigator to be mild in severity and not related to the study drug. No other serious AEs were reported during the lead-in or extension studies for patients enrolled in either study.

There were no deaths during the lead-in or extension studies.

No suicidal thoughts or behaviors were reported on the C-SSRS by children enrolled in the extension study either at the lead-in study screening assessment (baseline C-SSRS assessment) or at any other assessment. Suicidal ideation was reported by 2 of the 20 adolescents on the baseline C-SSRS evaluation at the lead-in study screening visit. One of those adolescents indicated suicidal ideation at subsequent visits during the lead-in study. Three adolescents reported suicidal ideation in the extension study, two of whom had also reported ideation during the lead-in study as noted. The one adolescent who reported new-onset suicidal ideation gave a “yes” response to one of the five items in the suicidal ideation section on a single assessment. The patient was assigned to desvenlafaxine 100 mg/day, and no dose change was made after report of suicidal ideation. The response was not reported as an AE, and the patient completed the 26 week extension study. No suicide attempts, preparatory acts toward imminent suicidal behavior, or self-injurious behavior were reported at the lead-in study baseline assessment, during the lead-in study, or during participation in the extension study.

Mean changes from lead-in study baseline are shown for selected laboratory test results in Table 2. Small but statistically significant changes from baseline were occasionally observed, but no patterns considered by the medical monitor to be clinically important were apparent. In all, 16 of 20 (80%) children and 17 of 20 (85%) adolescents had a laboratory value that met prespecified criteria for potential clinical salience at some time during the treatment period. Laboratory values reported for six children and seven adolescents were determined to be of clinical importance by the medical monitor. All clinically important changes were positive urine protein albumin tests, one of which occurred during the poststudy period. Twelve of the 13 clinically important urine protein albumin results were 1+ positive and the other was 2+ positive. Only three patients with clinically important results had a 1+ positive result at the extension study final evaluation (including the patient who had had a 2+ positive result); two had a 1+ positive result at the poststudy evaluation.

Table 2.

Baseline Mean and Mean Changes from Baseline at Final Evaluation for Selected Laboratory Tests: Safety Population

| Children | Adolescents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline mean | Mean change from baseline | n | Baseline mean | Mean change from baseline | |

| AST/SGOT (U/L) | 20 | 26.3 | −2.6 | 20 | 21.8 | 0.9 |

| ALT/SGPT (U/L) | 20 | 17.8 | 0.2 | 20 | 15.9 | −0.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 20 | 298.5 | −11.6 | 20 | 215.1 | −8.5 |

| Total cholesterol /lipid (mg/dL) | 14 | 157.1 | −2.7 | 13 | 157.9 | −8.1 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 14 | 58.3 | −2.3 | 13 | 51.7 | −0.8 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 14 | 78.4 | −1.5 | 13 | 89.2 | −6.2 |

| Triglycerides /lipid (mg/dL) | 14 | 102.1 | 5.8 | 13 | 85.0 | −3.1 |

ALT/SGPT, alanine aminotransferase/serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; AST/SGOT, aspartate aminotransferase/serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Mean changes from lead-in study baseline for vital sign results are shown in Table 3. There were statistically significant increases in pulse rate from lead-in study baseline to final evaluation for both groups; no statistically significant change in blood pressure was observed at final evaluation. Both children and adolescents had a statistically significant adjusted mean increase in height from lead-in study baseline to final evaluation; children had a statistically significant adjusted mean increase in weight at final evaluation. All (100%) of the children enrolled in the 6 month extension and 19 of 20 (95%) adolescents had at least one vital sign or body weight result that met prespecified criteria for potential clinical importance at some time during the combined lead-in and extension study treatment period. Five children (0 adolescents) had elevations in blood pressure that were considered to be clinically important by the medical monitor. In each case, the elevations trended toward prestudy baseline prior to the end of the active treatment study phase, and two cases resolved completely by the end of the extension trial. None of these occurrences were considered by the investigators to require withdrawal or dose changes based on these findings. No increases or decreases in weight reported for individual patients during the lead-in study or extension were determined to be clinically important by the medical monitor.

Table 3.

Baseline Mean and Mean Changes from Baseline at Final Evaluation for Vital Signs: Safety Population

| Children | Adolescents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline mean (SD) | Change from baseline mean (SE) | n | Baseline mean | Change from baseline mean (SE) | |

| Weight (kg) | 20 | 40.0 (10.7) | 3.8 (0.7)* | 20 | 68.3 (22.1) | 1.3 (0.9) |

| Height (cm) | 20 | 142.3 (8.0) | 2.8 (0.5)* | 20 | 164.1 (9.0) | 1.9 (0.6)** |

| Systolic BP, supine (mm Hg) | 20 | 111.2 (7.2) | −1.8 (2.1) | 20 | 116.4 (9.6) | 3.6 (2.0) |

| Diastolic BP, supine (mm Hg) | 20 | 66.2 (8.3) | −1.8 (2.4) | 20 | 67.6 (6.2) | 0.9 (1.8) |

| Pulse, supine (beats/min) | 20 | 77.3 (8.3) | 5.2 (2.4)*** | 20 | 73.7 (7.1) | 5.9 (2.0)** |

p<0.001 vs baseline.

p<0.01 vs baseline.

p<0.05 vs baseline.

BP, blood pressure.

The only statistically significant ECG results observed at final evaluation were a statistically significant decrease in QTCB interval (–10.21 msec, SE 4.26; p<0.05) and a statistically significant increase in QRS interval (+3.40 msec, SE 1.39; p<0.05) in adolescents. ECG results meeting prespecified criteria for potential clinical importance were observed in 14 of 20 (70%) children and 11 of 20 (55%) adolescents during the combined lead-in and extension study treatment period. No ECG results were considered clinically relevant by the medical monitor.

Efficacy

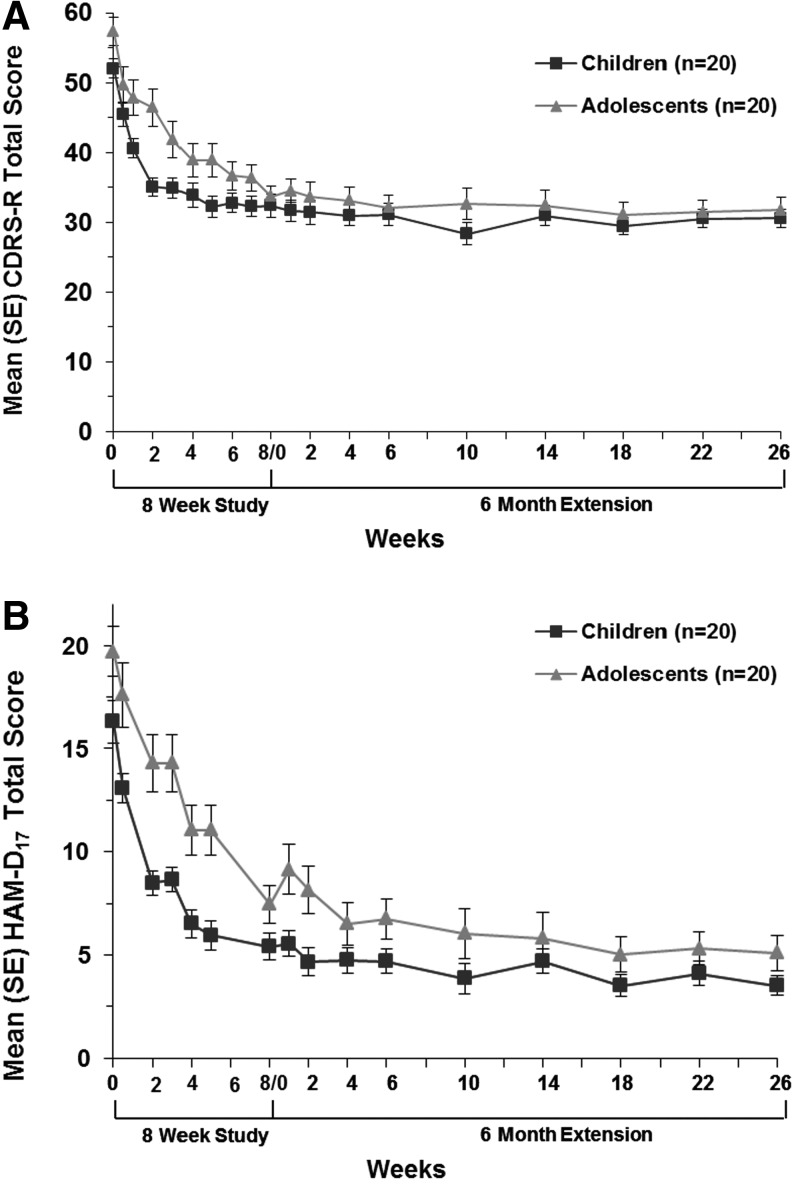

Children had a mean (SD) decrease from baseline in CDRS-R total score of 19.65 (9.94) during the lead-in study, and adolescents' score decreased by 23.65 (9.55). Reductions in CDRS-R scores observed at the end of the lead-in study were maintained through 6 months of flexible-dose desvenlafaxine treatment in both children and adolescents (Fig. 2A). The mean (SD) change from lead-in study baseline to week 26 of the extension study was –21.45 (8.00) for children and –25.60 (11.40) for adolescents. Similarly, mean HAM-D17 total scores for children and adolescents were reduced substantially from baseline during the lead-in study (–10.90 [5.11] and –12.25 [5.27], respectively), and a sustained reduction in mean HAM-D17 total score was observed for both groups during the 6 month extension (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Mean (SE) Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) total score by age strata, intent-to-treat population (last observation carried forward). (B) Mean (SE) 17 item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) total score by age strata, intent-to-treat population (last observation carried forward).

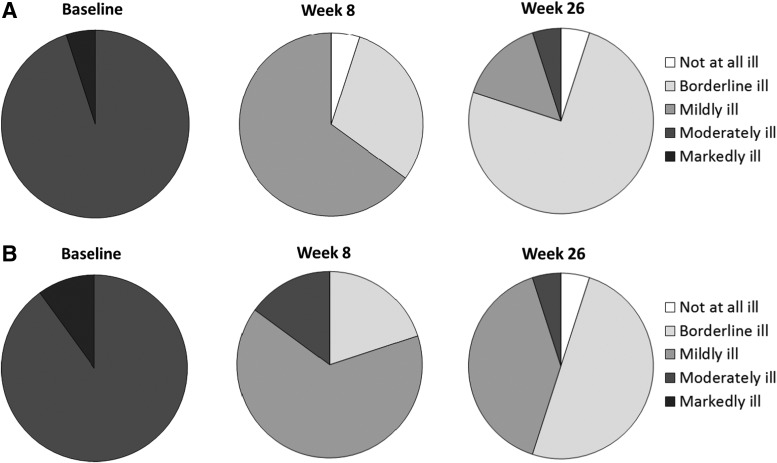

At lead-in study baseline, 19 of 20 children and 18 of 20 adolescents had a CGI-S score of 4 (moderately ill); the remainder had a CGI-S score of 5 (markedly ill). After 8 weeks of desvenlafaxine treatment, the distribution of CGI-S scores had generally shifted toward a score of 3 (mildly ill) or 2 (borderline ill) for both age groups (Fig. 3). By the end of the 6 month extension (LOCF), the majority of children were “borderline ill” (15/20 [75%]), and 90% of adolescents were either “mildly ill” (8/20 [40%]) or “borderline ill” (10/20 [50%]).

FIG. 3.

Clinical Global Impressions–Severity of Illness Scale (CGI-S) scores using lead-in study day −1 as baseline, intent-to-treat population (last observation carried forward). (A) Children. (B) Adolescents.

The proportion of patients who had responded to treatment (CGI-I score of 1 or 2) at lead-in study week 8 was 75% for children and 70% for adolescents. At the time of their final evaluation (extension week 26, LOCF), 85% of children and 85% of adolescents met the criterion for response. Remission rates (CDRS-R total score ≤28) at lead-in study week 8 were 25% for children and 15% for adolescents; 30% of children and 30% of adolescents met the criterion for remission at extension study final evaluation.

Discussion

Open-label, flexible-dose desvenlafaxine was generally safe and well tolerated in 20 children (doses 10–100 mg/day) and 20 adolescents (doses 25–200 mg/day) in this 8 week lead-in and 6 month extension trial, although results must be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size. The most common TEAEs reported by children and adolescents in this study were similar to those listed in short-term and long-term desvenlafaxine trials in adult patients with MDD (Clayton et al. 2009; Tourian et al. 2011; Rosenthal et al. 2013). Statistically significant mean weight loss has been reported during short-term desvenlafaxine treatment in adult patients (Clayton et al. 2009), but was not observed at any time point in children or adolescents in these studies. Weight gain was expected over the duration of the study in growing children. Both children and adolescents had a statistically significant mean increase in height over the course of the studies (2.8 cm and 1.9 cm, respectively), and children had statistically significant weight gain (3.8 kg) commensurate with their increase in height; adolescents' mean weight gain (1.3 kg) was not statistically significant. No patients had clinically important weight loss (or weight gain) during the trial. Individual elevations in blood pressure deemed clinically important by the medical monitor were observed at some time points for some children; elevations in blood pressure generally subsequently trended toward prestudy baseline without dose adjustments.

The assessment of efficacy in these studies was exploratory; a placebo control group was not used in either study, and hypothesis testing was not conducted. For both children and adolescents, CDRS-R and HAM-D17 total scores numerically decreased over the 8 weeks of the lead-in study, and maintained the reduction over 6 months of continuation therapy. In these studies, scores were similar for child and adolescent patients, except that children's scores may have decreased more rapidly than adolescents during the first several weeks of treatment. Placebo-controlled studies would be necessary, however, to demonstrate whether desvenlafaxine has efficacy in either age group.

The risk of treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and behavior is a concern with antidepressant treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs, particularly in patients <25 years of age (Laughren 2006). An increased relative risk of suicidal ideation and behavior with antidepressant treatment with SSRIs has been reported in an analysis of 24 pediatric clinical trials (Hammad et al. 2006). No completed suicides were reported in any of the pediatric trials, but there was an increase in risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in pooled data from all antidepressants in the analysis for all indications (risk ratio [RR]: 1.95; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.28–2.98) and for SSRIs in depression trials (RR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.02–2.68) (Hammad et al. 2006). Although no clear evidence of treatment-emergent suicidal thought or behaviors was observed with desvenlafaxine treatment in the current study—1 of 20 adolescents in the safety population (0 children) experienced suicidal ideation at a single postbaseline assessment that was not present at baseline—no conclusions can be drawn; because of the small sample size. Because event rates are low, the association between SSRIs/SNRIs and suicidal ideation and behavior may need to be evaluated in pooled data from multiple trials. No increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors was observed in a retrospective analysis of pooled data from nine desvenlafaxine trials in adults; however, no data for children or adolescents treated with desvenlafaxine were available for that analysis (Tourian et al. 2010). With any SSRI or SNRI, clinicians should monitor for treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents treated for MDD (Cheung et al. 2007).

Antidepressant therapy, together with supportive treatment or psychotherapy, is the recommended first or second line treatment for children and adolescents with moderate or severe MDD (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2005; Birmaher et al. 2007; Cheung et al. 2007; Garland et al. 2009; Lexapro® package insert, 2011), but effective antidepressant options for children and adolescents are limited. Fluoxetine (compared with cognitive behavior therapy or the combination) (March et al. 2007), venlafaxine (Emslie et al. 2007), and sertraline (Ambrosini et al. 1999; Nixon et al. 2001; Rynn et al. 2006) have been assessed in maintenance or extension studies of children or adolescents with MDD. Venlafaxine and sertraline were reported to be generally well tolerated, with adverse event profiles similar to those previously reported in other populations (Ambrosini et al. 1999; Nixon et al. 2001; Rynn et al. 2006; Emslie et al. 2007); only suicide-related long-term safety outcomes were reported for fluoxetine (March et al. 2007). Discontinuation rates were 22% for fluoxetine, 38–54% for sertraline, and 58% for venlafaxine in 6 month trials (Nixon et al. 2001; Rynn et al. 2006; Emslie et al. 2007; March et al. 2007). Conclusions about efficacy were limited in those studies because of the lack of a placebo control.

Limitations

The current studies, similarly, had several limitations. Most importantly, small sample size and the lack of a placebo control limit the interpretation of any efficacy data. All efficacy analyses were, therefore, considered exploratory, and the results are interpreted only as indicating that placebo-controlled desvenlafaxine trials in children and adolescents would be indicated. Interpretation of the safety data is also limited by the lack of placebo control and the small study population, and conclusions are based on desvenlafaxine exposure of up to 8 months. Because of the use of inclusion and exclusion criteria to select a medically uncomplicated sample, results may not generalize to the general pediatric patient population with MDD. In addition, reasons for not continuing were not captured for patients who completed the lead-in study but did not enter the extension study. This is another limitation.

Conclusions

Long-term treatment (up to 8 months) with desvenlafaxine appears to be generally safe and well tolerated in children and adolescents at the doses studied. Placebo-controlled efficacy and safety studies of desvenlafaxine in children and adolescents are warranted.

Clinical Significance

Clinical guidelines recommend the use of antidepressant drugs together with psychotherapy (such as cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy) in children or adolescents with moderate to severe MDD. However, few FDA-approved pharmacological treatments are available. Long-term treatment (up to 8 months) with desvenlafaxine appears to be generally safe and well tolerated in children and adolescents with MDD at the doses studied. Efficacy assessments were exploratory.

Disclosures

Dr. Findling receives or has received research support from, acted as a consultant for, received royalties from, and/or served on a speaker's bureau for Abbott, Addrenex, Alexza, American Psychiatric Press, AstraZeneca, Biovail, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Guilford Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Physicians' Postgraduate Press, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Seaside Therapeutics, Sepracor, Shionogi, Shire, Solvay, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Validus, WebMD and Wyeth. Deborah Chiles, Sara Ramaker, and Lingfeng Yang are employees of Pfizer. James Groark and Karen A. Tourian were employees of Pfizer at the time this work was conducted. Medical writing support was provided by Dr. Kathleen M. Dorries of Peloton Advantage, and was funded by Pfizer.

References

- Ambrosini PJ, Wagner KD, Biederman J, Glick I, Tan C, Elia J, Hebeler JR, Rabinovich H, Lock J, Geller D: Multicenter open-label sertraline study in adolescent outpatients with major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:566–572, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameter on the use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:961–973, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 123:1223–1228, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent D, Bernet W, Bukstein O, Walter H, Benson RS, Chrisman A, Farchione T, Greenhill L, Hamilton J, Keable H, Kinlan J, Schoettle U, Stock S, Ptakowski KK, Medicus J: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:1503–1526, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Perel J, Nelson B: Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:1427–1439, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P, Montgomery S, Lepola U, Germain JM, Brisard C, Ganguly R, Padmanabhan SK, Tourian KA: Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fixed-dose desvenlafaxine 50 and 100 mg/day for major depressive disorder in a placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 23:243–253, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE: Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics 120:e1313–e1326, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua HC, Chan LL, Chee KS, Chen YH, Chin SA, Chua PL, Fones SL, Fung D, Khoo CL, Kwek SK, Lim EC, Ling J, Poh P, Sim K, Tan BL, Tan CH, Tan LL, Tan YH, Tay WK, Yeo C, Su HC: Ministry of Health clinical practice guidelines: Depression. Singapore Med J 53:137–143, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AH, Kornstein SG, Rosas G, Guico–Pabia C, Tourian KA: An integrated analysis of the safety and tolerability of desvenlafaxine compared with placebo in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr 14:183–195, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Yeung PP, Kunz NR: Long-term, open-label venlafaxine extended-release treatment in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr 12:223–233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency: International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use (ICH). E6 R1. Guideline for good clinical practice. Updated: July, 2002. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002874.pdf Accessed March20, 2012

- Findling RL, McNamara NK, Stansbrey RJ, Feeny NC, Young CM, Peric FV, Youngstrom EA: The relevance of pharmacokinetic studies in designing efficacy trials in juvenile major depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:131–145, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EJ, Kutcher S, Virani A: 2008 position paper on using SSRIs in children and adolescents. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18:160–165, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W: Clinical Global Impressions. In: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp. 217–222 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62, 1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J: Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:332–339, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries MK: Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biol Psychiatry 49:1002–1014, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughren TP: Overview for December 13 meeting of psychopharmacologic drugs advisory committee (PDAC) [memorandum]. Updated: November16, 2006. Available at http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-FDA.pdf Accessed April19, 2012

- Lexapro [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ: Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:633–639, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Manley AL, Padmanabhan SK, Ganguly R, Tummala R, Tourian KA: Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/day and 100 mg/day in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 24:1877–1890, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, Burns B, Domino M, McNulty S, Vitiello B, Severe J: The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1132–1143, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ML, Thompson M, Santosh PJ, Wong IC: Effects of the Committee on Safety of Medicines advice on antidepressant prescribing to children and adolescents in the UK. Drug Saf 28:1151–1157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: Depression in children and young people: Identification and management in primary, community and secondary care. Clinical Guideline 28. Updated: September, 2005. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG028 Accessed April19, 2012

- National Institutes of Health: World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Updated: 2004. Available at http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/helsinki.html Accessed March20, 2012

- Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, Charney DS, Lenderts SE, Cascade EF, Stephenson H, Schatzberg AF: Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:466–472, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon MK, Milin R, Simeon JG, Cloutier P, Spenst W: Sertraline effects in adolescent major depression and dysthymia: A six-month open trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 11:131–142, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ: The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168:1266–1277, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ: A depression rating scale for children. Pediatrics 64:442–450, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pristiq [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal JZ, Boyer P, Vialet C, Hwang E, Tourian KA: Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/d for prevention of relapse in major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 74:158–166, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynn M, Wagner KD, Donnelly C, Ambrosini P, Wohlberg CJ, Landau P, Yang R: Long-term sertraline treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:103–116, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Kornstein SG, Germain JM, Jiang Q, Guico–Pabia C, Ninan PT: An integrated analysis of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine compared with placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr 14:144–154, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourian KA, Padmanabhan K, Groark J, Ninan PT: Retrospective analysis of suicidality in patients treated with the antidepressant desvenlafaxine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 30:411–416, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourian KA, Pitrosky B, Padmanabhan SK, Rosas GR: A 10-month, open-label evaluation of desvenlafaxine in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 13:ii, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AP, Ben-Hamadi R, Wu EQ, Kaltenboeck A, Bergman R, Xie J, Blum S, Erder MH: Impact of initiation timing of SSRI or SNRI on depressed adolescent healthcare utilization and costs. J Med Econ 14:508–515, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]