Kinases have become one of the most important families of drug targets for many diseases and for cancer in particular (Zhang et al., 2009). The current popularity is driven by several reasons: (1) kinases are often involved in signal transduction cascades so that inhibiting a given kinase is an effective way of inhibiting an entire pathway, (2) despite a high degree of conservation within the ATP cofactor binding site of kinases, of which there are over 500, subtle differences proximal to the kinase active site as well as the use of kinase specific allosteric sites can be exploited to develop potent and reasonably selective inhibitors, (3) inhibition of kinase function in normal cells can often be tolerated offering a therapeutic window for the killing of cancer cells, and (4) the success of Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) in inhibiting the kinase activity of the ABL tyrosine kinase in the BCR-ABL fusion protein (although the inhibitor also potently inhibits other kinases such as KIT and PDGFR) with a 5-year progression-free survival of over 95% in patients with chronic myeloid leukemias (CML) demonstrates that kinase inhibitors can be successfully used to treat cancer. Despite these motivating factors, the development of the next therapeutically useful kinase inhibitor faces several obstacles including kinase selectivity, efficacy in cells and drug resistance. Indeed, some CML cases show primary resistance to Gleevec or they relapse after an initial response (Volpe et al., 2009). Because of this, preclinical and clinical studies are underway to develop drugs to treat CML cases that show resistance to Gleevec and to develop dug regimens that might prevent such resistance.

Several other kinase pathways are being targeted for inhibition for various cancer indications and one of the most investigated such pathways is the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway that has elevated activity in several cancers and in malignant melanoma in particular. In this signaling pathway, RAS proteins stimulate the activity of the kinase cascade of RAF, MEK and ERK to signal to the nucleus to transmit cell proliferation and survival signals (McCubrey et al., 2007). When rendered constitutively active in cancer, the MAP kinase pathway sustains tumor viability, a state called “oncogenic dependency.” In melanoma, deregulation of the MAP kinase pathway occurs predominantly through a V600E gain of function mutation in the B-RAF kinase (called BRAFV600E). Because of this, B-RAF and to a lesser extent MEK have surfaced as important clinical targets for melanoma, and several B-RAF (for example RAF265, PLX4032 and XL281) and MEK (for example AZD6244 and XL518) inhibitors are in phase I or II clinical trials (McCubrey et al., 2007). Given the interest in the MAP kinase pathway in melanoma treatment, designing regimens with therapeutic efficacy while also addressing the potential emergence of drug resistant mutations will be an important consideration.

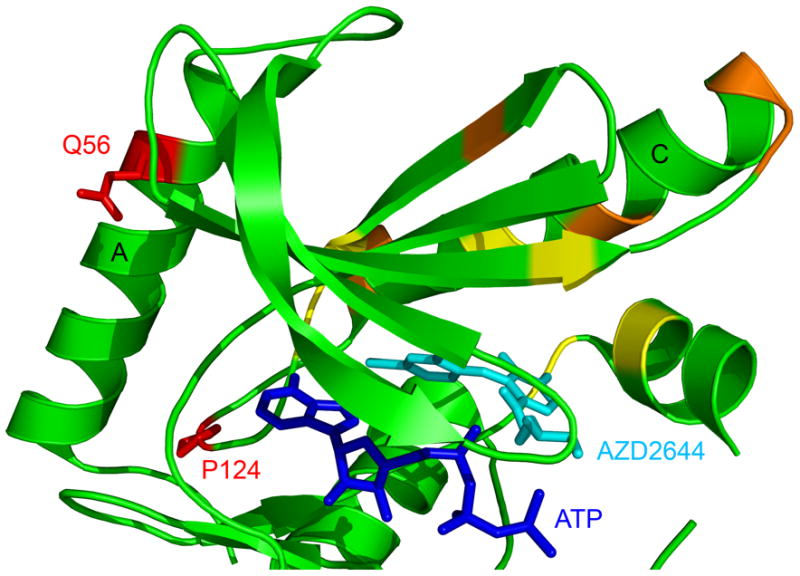

The manuscript by Emery et al. (Emery et al., 2009) presents the results of experiments designed to survey the landscape of drug resistant mutations that develop upon drug inhibition of MEK (MEK1 and MEK2). To do this, the authors subjected BRAFV600E derived melanoma cells that had acquired resistance to the allosteric MEK inhibitor, AZD6244, to a random MEK1 mutagenesis screen followed by massively parallel sequencing to derive the spectrum of MEK1 resistant mutations. Together with additional sequencing using the Sanger method, this resulted in over 1,000 resistant clones, vastly exceeding the scope of prior mutagenesis. Not surprisingly, the authors identified several MEK1 resistant alleles that formed the primary or secondary shell of the AZD6244 drug binding site (Figure 1) suggesting that these mutants destabilize drug binding. This was confirmed for each of these mutants, as the authors showed significantly elevated GI50 values (between 50- and 1000-fold) upon treatment with AZD6244 in cells. Unexpectedly, a second class of drug resistant mutations were identified distal to the AZD6244 binding pocket. Three were located in the C-terminal kinase domain (P326L, G328R and E368K) and two others were located in the N-terminal kinase domain; one on an N-terminal regulatory helix A (Q56P) and another in a loop located between helix A and helix C (P124 to S or Q) (Figure 1). Due to their distance from the AZD6244 binding site, the authors reasoned that this second class of mutations were unlikely to perturb AZD6244 drug binding but instead upregulate intrinsic MEK1 activity. The authors further analyzed the second class of mutations within the N-terminal domain and showed that the Q56P mutant indeed harbored higher intrinsic MEK1 activity in vitro. The P124S and P124L mutants, however, had wild-type kinase activity in vitro suggesting that these mutations require AZD6244 drug binding for elevated kinase activity. Taken together, it was surprising that the authors identified drug resistant mutations that functioned independently of a reduction in drug binding affinity, suggesting that, more generally, drug resistant mutants need not arise from the direct reduction of drug binding. Correlating with the mutational sensitivity of Q56 and P124, T55P and P124L are germline variants observed in patients with cardio-facio-cutaneous (CFC) syndrome that confer aberrant MEK activation.

Figure 1.

Drug resistant MEK1 mutations mapped onto the MEK1 structure in complex with ATP and the AZD6244 allosteric inhibitor. The structure was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (accession number 3EQC). Only the N-terminal kinase domain of MEK1 is shown as a cartoon with the ATP and AZD6244 molecules shown as stick figures. MEK1 drug resistant mutations identified in the mutagenesis screen are color coded for primary mutations that are in the first (yellow) or second (orange) shell of AZD6244 drug binding or that are distal to the drug binding site (red). Helices A and C are also indicated. The three drug resistant mutations identified in the C-terminal kinase domain are not shown for clarity.

To determine if the “simulated resistance” mechanism might be relevant to the clinical response to MEK inhibition, the authors also carried out deep sequencing of MEK1 DNA from tumors of 7 advanced melanoma patients enrolled in phase II clinical trials with AZD6244. The authors targeted exons 3 and 6 for sequencing, covering several of the validated resistance alleles (but not Q56) that were identified in the mutagenesis screen of MEK1. One patient was identified to have a mutant allele in exon 3 encoding a P124L substitution. Interestingly, this mutation was identified in the post-relapse tumor of this patient treated with AZD6244 but not in the pre-relapse tumor, consistent with this mutation arising from drug treatment. These studies confirm the clinical resistance mechanism identified in the random mutagenesis screen.

Given the interest in targeting BRAF in melanoma, the authors investigate the effect of targeting AZD6244-resisitant primary melanoma cells with the B-RAF selective inhibitor PLX4720. The authors found a profound cross-resistance of these cells to drug treatment. The authors then investigated the effect of PLX4720 treatment on MEK resistant primary alleles (AZD6244 binding mutants) and secondary alleles (P124L, P124S and Q56P) and found that while the expression of primary alleles had only a modest effect on the GI50 of PLX4720, expression of the secondary alleles had differing degrees of resistance to PLX4720 treatment. Taken together, these studies show that clinically relevant MEK1 drug resistant secondary allele mutants confer cross-resistance to B-RAF inhibition.

Finally, the authors investigated whether the stringency of MAP kinase pathway inhibition might influence the emergence of on-target resistance mutants. Strikingly, the authors found that the combined exposure of melanoma cells to AZD6244 and PLX4720 potently suppressed the emergence of MEK1 resistant variants, raising the possibility that combined B-RAF and MEK inhibition might circumvent acquired resistance to MAP kinase pathway targeted therapies.

The study by Emery et al. raises several important issues underlying drug resistance in cancer treatment. Most surprising is the identification of drug resistant mutations at sites distal to the drug-binding site creating intrinsic kinase activation. Although it would be of significant mechanistic interest to understand how such mutations increase intrinsic kinase activity, the study makes clear that such mutations must be anticipated ahead of time for developing an optimal therapeutic treatment. Indeed, the authors demonstrate that one effective way to do this is to use combination therapy to inhibit two kinases within a single signaling pathway. In this way, it is more difficult for drug resistant mutations to arise. The effectiveness of Gleevec may indeed be due to the fact that, in addition to being a potent inhibitor for ABL kinase, it also cross-reacts with other kinases. Several studies have also shown that mutation of a kinase in one pathway, such as the MAP kinase pathway, may result in elevated kinase activity in another pathway such as the PI3K-AKT pathway. Therefore, combination therapy that targets multiple kinase pathways might also be considered and combination therapy that targets both the MAP and PI3K-AKT pathways has been previously proposed (for example (Smalley and Flaherty, 2009)). An interesting follow-up of the current study would be to sequence other kinases within the MAP kinase pathway such as BRAF and ERK, as well as kinases in the PI3K-AKT pathway to establish a more complete spectrum of drug resistant mutations that might arise as a response to targeted inhibition of the MAP kinase pathway. What is clear is that kinases have evolved a clever mechanism of drug evasion and the more we understand about this the more likely we are to develop effective therapeutic cancer treatments in the future.

References

- Emery CM, Vijayendran KG, Zipser MC, Sawyer AM, Niu L, Kim JJ, et al. MEK1 mutations confer resistance to MEK and B-RAF inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905833106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EW, Chang F, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KS, Flaherty KT. Integrating BRAF/MEK inhibitors into combination therapy for melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:431–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe G, Panuzzo C, Ulisciani S, Cilloni D. Imatinib resistance in CML. Cancer Lett. 2009;274:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]