Abstract

Wild Alaskan Vaccinium berries, V. vitis-idaea (lowbush cranberry) and V. uliginosum (bog blueberry), were investigated in parallel to their commercial berry counterparts; V. macrocarpon (cranberry) and V. angustifolium (lowbush blueberry). Lowbush cranberry accumulated about twice the total phenolics (624.4 mg/100 g FW) and proanthocyanidins (278.8 mg/100 g) content as commercial cranberries, but A-type proanthocyanidins were more prevalent in the latter. Bog blueberry anthocyanin and total phenolic contents of 220 and 504.5 mg/100 g, respectively, significantly exceeded those of the lowbush blueberry. Chlorogenic acid, however, was quite high in lowbush blueberry (83.1 mg/100 g), but undetected in bog blueberry, and the proanthocyanidins of lowbush blueberry had significantly higher levels of polymerization. Antioxidant capacity (DPPH, APTS and FRAP) correlated with phenolic content for each berry. A polyphenol-rich fraction from lowbush cranberry exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of LPS-elicited induction of IL-1β in RAW 264.7 cells, indicative of strong anti-inflammatory activity. These results corroborate the historic use of wild Alaskan berries as medicinally-important foods in Alaska Native communities.

Keywords: Vaccinium vitis-idaea, V. uliginosum, V. macrocarpon, V. angustifolium, phenolics, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies have shown that increased consumption of fruits and vegetables correlates with improved cardiovascular health as well as reduced cancer, stroke, degenerative diseases, loss of functionality associated with aging, and more.1–3 While fruits and vegetables are rich sources of vitamins and minerals, recent attention in biomedical research has focused heavily on phenolic components, flavonoids in particular, for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other health-relevant bioactivities.4–6 Although not fully understood, these health-promoting effects have been mainly related to interactions between the phenolic compounds and several key enzymes, signaling cascades involving cytokines and regulatory transcription factors, and antioxidant systems.7

Many types of wild berries are indigenous to in Alaska, and seasonal harvests are major community events especially in rural Alaska Native villages. Wild Alaskan berries are delicious fresh, frozen, dried, or turned into any number of tasty creations: jams, muffins, fruit leathers, sauces, and agutuk (otherwise known as Alaskan/Eskimo ice cream, made from seal oil and berries).8 People commonly harvest berries of the Vaccinium genus, blueberries, lowbush cranberries, and other wild berries, when the berries are ripe in July, August, and September, and use them both for food and medicine. The summer season is short, and the day-length of summer is dramatically longer than that found at lower latitudes, which can have a profound impact on the phytochemical composition and content of the fruits.9

The genus Vaccinium includes several popular commercial berry species, including lowbush, highbush and rabbiteye blueberries, domesticated cranberries and lingonberries. In general, Vaccinium berry fruits are widely renowned for their health benefits, reportedly due to their high concentrations of phenolic compounds, and/or due to the presence of specific, particularly potent polyphenolic compounds which may interact (additively or synergistically) to ameliorate human health conditions.10

The influence of the growing environment on both phenolic concentrations and profiles has been previously described,11,12 which could condition the health-relevant potency of berries from wild and cultivated regimes. However, the composition and merits of most wild Vaccinium selections have not been well documented. In this study, we comparatively examined two wild Alaskan berry species; lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea, also known as lingonberry or cowberry in many other parts of the world) and bog blueberry (V. uliginosum, also known as alpine blueberry or bilberry), and their corresponding commercial counterparts; American cranberry (V. macrocarpon) and lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium), because considerable baseline data has already been generated for the latter two, commercially-cultivated species. V. vitis-idaea and V. uliginosum are among the most significant wild berries in Nordic countries, Russia, and other circumpolar regions, and their phenolic profiles have been investigated previously.13,14 However, only scant analysis has been conducted to determine phytochemical profiles or anti-inflammatory bioactivity of these species in Alaska. Streamlined and sophisticated analytical protocols were applied to rigorously establish and cross-compare the phytochemical profiles and antioxidant capacity of these berries, in order to provide information on their potential suitability for different applications. Also, the effect of berry extracts on the expression of four well-known genetic biomarkers of inflammation was investigated in vitro in a lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine RAW 264.7 macrophage model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Materials

Reference compounds procyanidin A2 (PAC-A2), procyanidin B2 (PAC-B2), catechin and epicatechin were purchased from Chromadex (Irvine, CA, USA). 4-Dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde (DMAC), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), 2,2'-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), 2,2'-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH), phosphate buffer, 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate, and fluorescein sodium salt (FL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All organic solvents were HPLC grade and obtained from VWR International (Suwanee, GA, USA).

Berry sources

Wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) and bog blueberry (V. uliginosum L.) were handpicked when fully ripe from the vicinity of Fairbanks, AK, USA. Lowbush cranberry was collected at latitude 64.8 N, longitude 147.7 W in September 2012. Bog blueberry was collected at latitude 65.5 N, longitude 145.4 W in July 2012. A total of three kg fruit were collected from each species in the growing region over a one week period. Berries were immediately stored at −80 °C before freeze-drying. Freeze-dried berries were ground before sampling and analysis. A composite sample of commercially-grown lowbush blueberries (V. angustifolium Aiton) was obtained from the Wild Blueberry Association of North America (Old Town, ME, USA). The blueberries were a composite of fruits from all major growing sites in Canada (Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec) and USA (Maine). The composite was made in the fall 2012, frozen by Cherryfield Foods, Inc. at −15 °C (Cherryfield, ME, USA), and subsequently stored at −80 °C. American cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait) were obtained from The Cranberry Network, LLC (Wisconsin Rapids, WI, USA) in fall 2012 and stored at −80 °C. Commercial berries (5 kg each) were freeze-dried and then ground prior to sampling and extraction. Dry matter (DM) percentage was calculated based on the difference between berry fresh weight (FW) and the weight after freeze-drying (FD). All extractions were performed on the freeze-dried material, and results were calculated on a fresh weight basis by considering the water content in each berry.

Extraction and Polyphenol Enrichment

Freeze-dried ground berry fruits (2.5 g × 3 replicates) were blended (Waring, Inc., Torrington, CT, USA) with 30 mL acidified 70% aqueous methanol (0.5% acetic acid) for 2 min. The mixture was centrifuged (Sorvall RC-6 plus, Asheville, NC, USA) for 20 min at 4000 rpm, and the supernatant was transferred to 100 mL volumetric flasks. The extraction of the pellet was repeated 2 more times and the combined extracts were brought to a final volume of 100 mL. Samples of crude extracts (CE) were filtered, using a 0.20 μm PTFE syringe filter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA), before analysis using HPLC, LC-MS and MS/MS, and antioxidant capacity bioassays. An aliquot of the crude extract (2 mL) was dried down completely before testing for anti-inflammatory activity, as described below. The crude extract (50 mL) was evaporated to about 2 mL before loading onto two SPE cartridges (Supelclean™ LC-18, 12 mL) preconditioned with methanol, and then acidified water (0.01% HCl). Each cartridge was washed with 50 mL acidified water before eluting with 100% methanol until all color eluted off. The methanol extract was evaporated and freeze-dried to get the polyphenol-rich fraction (PRE) which was subjected to HPLC, LC-MS analyses and anti-inflammatory bioassays.

Determination of Total Phenolics, Anthocyanins and Proanthocyanidins

The CE from each berry was diluted to appropriate concentrations for analysis. Total phenolics (TP) were determined with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent by the method of Singleton.15 Concentrations were expressed as mg/L gallic acid equivalents based on a created gallic acid standard curve. Total monomeric anthocyanin (ANC) content was measured by the pH differential spectrophotometric method,16 using a Shimadzu UV-2450 (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) spectrophotometer. ANC concentration was calculated as mg/L cyanidin 3-O-glucoside equivalents. Total proanthocyanidins (PAC) concentration was determined colorimetrically using the DMAC method in a 96-well plate as previously described.17 A series of dilutions of standard procyanidin A2 dimer were prepared in 80% ethanol ranging from 1–100 μg/mL. Blank, standard and diluted samples were analyzed in triplicates. The plate reader protocol was set to read the absorbance (640 nm) of each well in the plate every minute for 30 min (SpectraMax® M3, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Concentration of PAC in the solution was expressed as mg/L procyanidin A2 equivalent.

Reversed Phase HPLC and LC-ESI-MS Analysis

HPLC analyses for anthocyanins were conducted using an Agilent 1200 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), according to our previously published protocol.18 Quantification of anthocyanins was performed using the peak areas recorded at 520 nm to construct the calibration curve for cyanidin-3-O-glucoside.

HPLC for chlorogenic acid was performed using a Phenomenex Synergi 4 μm Hydro-RP 80A column (250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 2% acetic acid in distilled H2O (solvent A) and 0.5% acetic acid in 50% acetonitrile in water (solvent B). The flow rate was set at 1 mL/min with a step gradient of 10%, 15%, 25%, 55%, 100% and 10% of solvent B at 0, 13, 20, 50, 54 and 60 min, respectively. Quantification was performed from the peak areas recorded at 280 nm to the calibration curve obtained with reference standard. LC-MS analysis was performed using a Shimadzu LC-MS-IT-TOF instrument, (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Prominence HPLC system. The LC separation was performed using a Shim-pack XR-ODS column (50 mm × 3.0 mm × 2.2 μm) at 40 °C with a binary solvent system comprised of 0.1% formic acid in water (A), and methanol (B). Compounds were eluted into the ion source at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min with a step gradient of B of 5–8% (0–5 min), 8–14% (10 min), 14% (15 min), 20% (25 min), 25% (85 min), 5% (35 min) and 5% (40 min). Ionization was performed using an ESI source in the negative ion mode. Compounds were characterized and identified by their MS, MS/MS spectra and LC retention times and by comparison with available reference samples and our previous analyses18,19.

Normal Phase HPLC-fluorescence Analysis of Proanthocyanidins

HPLC analyses were conducted using an Agilent 1200 HPLC with fluorescence detector (FLD) and photodiode array detector (DAD). Proanthocyanidin separation was performed according to Wallace and Giusti,20 using a Develosil Diol column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). PAC were identified by comparison with available standards, our previous analyses,18 reported literature,20 and LC-ESI-MS. Quantification of proanthocyanidin was calculated using peak areas and a calibration curve for procyanidin-A2, and amounts were expressed as procyanidin-A2 equivalents.

Free Radical Scavenging (DPPH Assay)

The radical scavenging activity was measured using the stable DPPH and Trolox as reference substances.21 Samples were diluted 10x with 80% methanol before mixing with the reagent. An aliquot (100 μL) of each sample was pipetted into 3.9 mL of DPPH solution (0.08 M in 95% ethanol) to initiate the reaction. After a reaction time of 3 hours at ambient temperature the reaction had reached completion. The decrease in absorbance of DPPH free radicals was read at 515 nm against ethanol as a blank using a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer. Trolox (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 μM) was used as a standard antioxidant compound. Analysis was performed in triplicate for each sample and each concentration of standard. The antioxidant activity was reported in μmol of Trolox equivalents per gram fresh weight (μmol TE/g FW).

Free Radical Scavenging (ABTS Assay)

The ABTS assay was performed as described by Re22 which is based on the reduction of ABTS+• radicals by antioxidants in the berry extracts. ABTS radical cation (ABTS+•) was produced by reacting ABTS solution (7 mM) with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (final concentration) and allowing the mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 12–16 h before use. For the assay, the ABTS+• solution was diluted in deionized water or ethanol to an absorbance of 0.7 (± 0.02) at 734 nm. After the addition of 100 μL of berry extract solutions to 3 mL of ABTS+• solution, the absorbance reading was taken at 30 °C 10 min after initial mixing (AE). All determinations were carried out in triplicate. The antioxidant activity was reported in μmol of Trolox equivalents per gram fresh weight (μmol TE/g FW).

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

This method is based on the reduction, at low pH, of a colorless ferric complex (Fe3+-tripyridyltriazine) to a blue-colored ferrous complex (Fe2+-tripyridyltriazine) by the action of electron-donating antioxidants. The ferric reducing power of berry extracts was performed in a 96-well microplate using the FRAP assay23 with minor modifications. The working FRAP reagent was prepared daily by mixing 10 volumes of 30 mM acetate buffer, pH 3.6, with 1 volume of 10 mM TPTZ in 40 mM hydrochloric acid and with 1 volume of 20 mM FeCl3. A standard curve was prepared using various concentrations of FeSO4. 7H2O. All solutions were used on the day of preparation. FRAP solution (175 μL) freshly prepared and warmed at 37 °C was added to three replicates of each sample (25 μL), while the same volume of acetate buffer was added to the fourth one (blank). The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, then the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. The absorbance of the blank was subtracted from the absorbance of the samples. In this assay, the reducing capacity of the extracts tested was calculated with reference to the reaction signal given by a Fe2+ solution. FRAP values were expressed as μmol Fe2+/g of fresh berry.

Macrophage Cell Culture

The mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 (ATCC TIB-71, obtained from American Type Culture Collection; Livingstone, MT, USA) was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, NY, USA), supplemented with 100 IU/mL penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin (Fisher) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) at a density not exceeding 5×105 cells/mL and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Anti-inflammatory in vitro Assay

Cells were subcultured by TrypLE™ (Life Technologies) when dishes reached up to 90% confluence with a 1:5 ratio in fresh medium. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) 24 h prior to treatment. The cells were then treated in triplicates with berry extracts at predetermined doses for 1 h before elicitation with LPS at 1 μg/mL for an additional 4 h. For every experiment, one positive control (cells treated with dexamethasone, [Dex], at 10 μM) and one negative control (cells treatment with vehicle) were included. Three replicates were made for both the treatments and the controls. At the end of the treatment period, cells were harvested in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) for subsequent cellular RNA extraction.

Cell Viability Assay and Dose Range Determination

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in a 96 well plate for the viability assay. Cell viability was measured by the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide] assay24 in triplicate and quantified spectrophotometrically at 550 nm using a microplater reader SynergyH1 (BioTek). The concentrations of test reagents that showed no changes in cell viability compared with that vehicle (ethanol) were selected for further studies.

Total RNA Extraction, Purification, and cDNA Synthesis

The total RNA was isolated from RAW macrophages using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically using the SynergyH1/Take 3 (BioTek, Winooski, VT). The cDNAs were synthesized using 2 μg of RNA for each sample using commercially available high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies), following the manufacturer's protocol on an ABI GeneAMP 9700 (Life Technologies).

Quantitative PCR Analysis

The resulting cDNA was amplified by real-time quantitative PCR using SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies). To avoid interference due to genomic DNA contamination, only intron-overlapping primers were selected using the Primer Express version 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as follows: ß-actin, forward primer: 5′-AAC CGT GAA AAG ATG ACC CAG AT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CAC AGC CTG GAT GGC TAC GT-3′; COX2, forward primer: 5′-TGG TGC CTG GTC TGA TGA TG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GTG GTA ACC GCT CAG GTG TTG-3′; iNOS, forward primer: 5′-CCC TCC TGA TCT TGT GTT GGA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TCA ACC CGA GCT CCT GGA A-3′; IL6, forward primer: 5′-TAG TCC TTC CTA CCC CAA TTT CC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TTG GTC CTT AGC CAC TCC TTC-3′; and IL1ß, forward primer: 5′-CAA CCA ACA AGT GAT ATT CTC CAT G-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GAT CCA CAC TCT CCA GCT GCA-3′. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplifications were performed on an ABI 7500 Fast real time PCR (Life Technologies) using 1 cycle at 50 °C for 2 min and 1 cycle of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. The dissociation curve was completed with 1 cycle of 1 min at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 95 °C. mRNA expression was analyzed using the ΔΔCT method and normalized with respect to the expression of the β-actin housekeeping genes using 7500 Fast System SDS Software v1.3.0 (Life Technologies). A value of less than 1.0 indicates transcriptional down-regulation (inhibition of gene expression) compared with LPS, which shows maximum genetic induction (1.0). Therefore, lower values indicate greater anti-inflammatory activity. Values higher than 1.0 imply overexpression of the particular gene in excess of LPS stimulation. Amplification of specific transcripts was further confirmed by obtaining melting curve profiles. A two-fold change in gene expression was determined to be sufficient to eliminate background noise, therefore 2-fold or higher values were used as a reliable estimation of relative expression ratio.25

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with treatment as a factor. Post hoc analyses of differences between individual experimental groups were made using the Dunnett's multiple comparison tests.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Total Monomeric Anthocyanins, Proanthocyanidins, Total Phenolics and Chlorogenic acid

Dry matter (DM) content of the berries used in this study ranged from 16% for commercial lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) to 24.6% for commercial American cranberry (V. macrocarpon). Wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry (V. vitis-idaea) and bog blueberry (V. uliginosum) contained 21.3% and 18.4% DM, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Polyphenol Content mg/100 g FW, Radical Scavenging Capacity (DPPH, ABTS μM Trolox Equivalent (TE)/g FW) and Ferric Reducing Capacity (FRAP as μM FeSO4/g FW) of Wild Alaskan and Commercial Vaccinium Species

| Berry Fruit | Dry matter % | ANCa mg/100 g | PACb mg/100 g | ChAc mg/100 g | TPd mg/100 g | DPPH μM TE/g | ABTS μM TE/g | FRAP μM Fe+2/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranberry (V. macrocarpon) | 24.6 ± 0.5A | 76.6 ± 3.2C | 132.7 ± 5.7B | 12.2 ± 0.2C | 350.5 ± 16.1C | 37.8 ± 0.1B | 35.8 ± 2.5C | 57.9 ± 4.1D |

| Lowbush Cranberrye (V. vitis-idaea) | 21.3 ± 0.5B | 194.6 ± 6.4B | 278.8 ± 19.6A | 18.3 ± 0.9B | 624.4 ± 34.2A | 51.3 ± 2.2 A | 69.3 ± 2.2A | 122.2 ± 4.6A |

| Lowbush Blueberry (V. angustifolium) | 16.0 ± 0.1D | 189.8 ± 8.0B | 71.2 ± 3.3C | 83.1 ± 1.0A | 371.3 ± 2 2C | 39.8 ± 1 2B | 40.1 ± 2.1C | 68.5 ± 4.3C |

| Bog Blueberrye (V. uliginosum) | 18.4 ± 0.3C | 220.0 ± 11.9A | 85.5 ± 5.9C | ND | 504.5 ± 32.2B | 46.5 ± 4.5A | 51.4 ± 0.1B | 100.3 ± 2.1B |

ANC: anthocyanins, quantified by pH differential assay as cyanidin-3-glucoside;

PAC: proanthocyanidins, quantified by DMAC assay as procyanidin A2.

ChA: chlorogenic acid, quantified by HPLC using reference standard.

TP: total phenolics, quantified by Folin Ciocalteu assay as gallic acid equivalent; ND: not detected. Means with different letters within the same column are significantly different at p < 0.05.

Wild species collected from Alaska.

Total anthocyanins (ANC) measured by pH differential assay indicated that the wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry contained comparable levels of ANC (194.6 ± 6.4 mg/100 g FW) to the commercial lowbush blueberry (189.8 ± 8.0 mg /100 g) but less than the wild Alaskan bog blueberry (220.0 ± 11.9 mg/100 g), while commercial cranberry contained significantly less ANC concentration (76.6 ± 3.2 mg/100 g) (Table 1). ANC content of wild lowbush cranberry was > 2.5 fold higher than that of commercial cranberry. In another study, V. vitis-idaea from Canada exhibited 1.4 fold greater ANC content than that of commercial cranberry, measured using the same assay.26 Conversely, other researchers estimated that V. vitis-idaea grown in Finland contained less ANC than European cranberry (257.0 and 299.3 mg/100 g, respectively, estimated by HPLC and based on dry weight).27 In our comparison, bog blueberry from Alaska accumulated the highest ANC concentration which is within the same range for this species grown in Northern Europe (155–256 mg/100 g FW).14,28

Proanthocyanidins (PAC), measured spectrophotometrically by DMAC assay, exhibited highest levels in wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry (278.8 ± 19.6 mg/100 g FW) which was comparable to the PAC content of the same species in Finland (260 mg/100 g FW).27 Commercial cranberry contained 132.7 ± 5.7 mg/100 g FW PAC; about half the PAC concentration of wild lowbush cranberry from Alaska. Wild Alaskan bog blueberry and commercial lowbush blueberry showed much lower levels of PAC (85.5 ± 5.9 and 71.2 ± 3.3 mg/100 g, respectively) with no significant difference at P < 0.05. Chlorogenic acid was highly accumulated in commercial lowbush blueberry (83.1 ± 1.0 mg/100g) but not detected in Alaskan bog blueberry. Wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry and commercial cranberry contained 18.3 ± 0.9 and 12.2 ± 0.2 mg/100 g chlorogenic acid, respectively. Total phenolics (TP) measured using Folin Ciocalteu assay and expressed as gallic acid equivalents were much higher for Alaskan lowbush cranberry (624.4 ± 34.2 mg/100 g) than for the other three species, and were comparable to same species grown in Canada.26 Second to lowbush cranberry, the Alaskan bog blueberry exhibited TP of 504.5 ± 32.2 mg/100 g, while both the commercial berries; cranberry and lowbush blueberry, contained 350.5 ± 16.1 and 371.3 ± 2.2 mg/100 g, respectively, with no significant differences (Table 1).

Anthocyanin Profiles of Berries

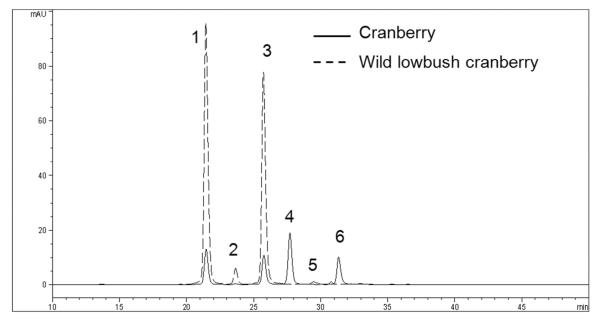

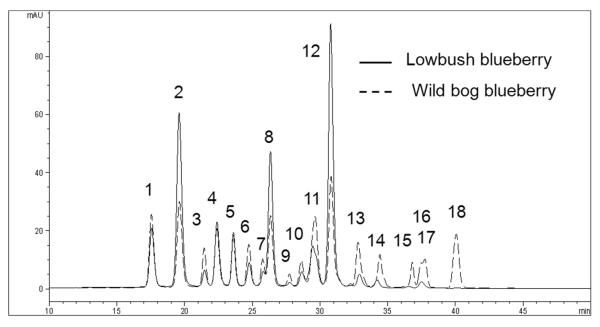

The HPLC-DAD chromatograms of anthocyanins for all four berries are illustrated in Figures 1 & 2. Commercial cranberry is known to contain 6 anthocyanins, which are the galactosides, glucosides and arabinosides of both cyanidin (peaks 1–3, 44%) and peonidin (peaks 4–6, 56%) (Table 2).29 Wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry displayed only cyanidin glycosides as the dominant anthocyanin, with non-detectable levels of peonidins. This agrees with the results reported on the same species grown in Finland.30 Environmental, geographical or other factors in the northernmost latitudes of Finland were linked to higher relative content of cyanidin glycosides. Cyanidin glycosides were also present in slightly higher concentration in blueberries from the northern latitudes (Norway and Sweden), while delphinidin glycosides were better represented in the berries from southern latitudes (Italy, Poland, and Romania).31 The HPLC chromatograms of Alaskan bog berry and commercial lowbush blueberry (Figure 2), and percentage of each anthocyanin (Table 2), indicated that the glucosides of delphinidin, petunidin and malvidin (peaks 2, 8 and 12) were highly represented in wild bog blueberry (21.6, 14.8, and 29.2%, respectively) as compared to commercial lowbush blueberry (11.0, 4.3, and 13.1%, respectively). On the other hand, while lowbush blueberry contained a total of 17.4% acylated anthocyanins, none of these derivatives were detected in wild bog blueberry, which concurs with a previous report on V. uliginosum recently collected from different regions of Alaska.9

Figure 1.

Reversed phase HPLC chromatograms for anthocyanins (A520) in crude extracts of commercial cranberry (V. macrocarpon) and wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry (V. vitis-idaea).

Figure 2.

Reversed phase HPLC chromatograms for anthocyanins (A520) in crude extracts of commercial lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium) and wild Alaskan bog blueberry (V. uliginosum).

Table 2.

Anthocyanin Composition in Wild Alaskan and Commercial Vaccinium Species Measured using RP-HPLC and UV Detection at 520 nm.

| Anthocyanin | % of Total ANCa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Number (Figure 1) | Cranberry (V. macrocarpon) | Lowbush Cranberryb (V. vitis-idaea) | |

| 1 | Cn-3-gal | 23.4 | 54.5 |

| 2 | Cn-3-glu | 0.7 | 3.2 |

| 3 | Cn-3-ara | 20.0 | 42.2 |

| 4 | Pn-3-gal | 34.6 | ND |

| 5 | Pn-3-glu | 2.6 | ND |

| 6 | Pn-3-ara | 18.7 | ND |

| Peak Number (Figure 2) | Lowbush Blueberry (V. angustifolium) | Bog Blueberryb (V. uliginosum) | |

| 1 | Dp-3-gal | 8.8 | 6.4 |

| 2 | Dp-3-glu | 11.0 | 21.6 |

| 3 | Cn-3-gal | 3.8 | 1.4 |

| 4 | Dp-3-ara | 6.3 | 7.1 |

| 5 | Cn-3-glu | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| 6 | Pt-3-gal | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| 7 | Cn-3-ara | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| 8 | Pt-3-glu | 4.3 | 14.8 |

| 9 | Pn-3-gal | 5.7 | 0.5 |

| 10 | Pt-3-ara | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| 11 | Mv-3-gal | 8.0 | 7.2 |

| 12 | Mv-3-glu | 13.1 | 29.2 |

| 13 | Mv-3-ara | 7.9 | 1.7 |

| 14 | Dp-3-(6″-acetoyl)-glu | 4.2 | ND |

| 15 | Cn-3-(6″-acetoyl)-glu | 2.6 | ND |

| 16 | Mv-3-(6″-acetoyl)-gal | 1.8 | ND |

| 17 | Pt-3-(6″-acetoyl)-glu | 2.5 | ND |

| 18 | Mv-3-(6″-acetoyl)-glu | 6.3 | ND |

Compounds were quantified based on peak area measurements. Cn : cyanidin; Pn: peonidin; Dp: delphinidin; Pt: petunidin; Mv: malvidin; gal: galactoside; glu: glucoside; ara: arabinoside.

Wild species collected from Alaska.

Proanthocyanin Profiles of Berries

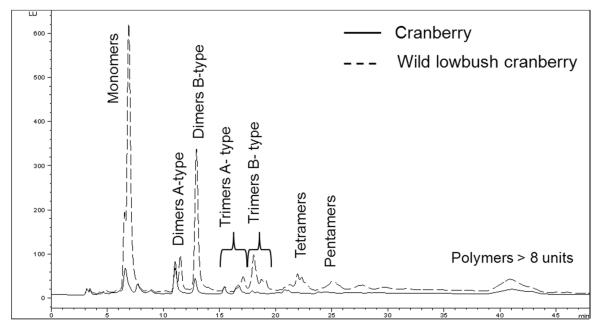

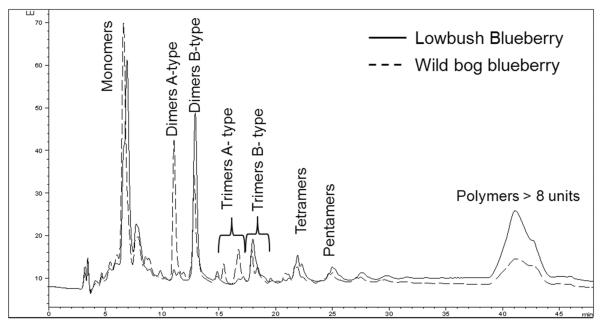

Normal phase HPLC with fluorescence detection was able to separate proanthocyanin components in the berry extracts according to their degree of polymerization (Figures 3 and 4). Commercial cranberry had higher percentages of A-type dimers and trimers (23.2 and 12.1%, respectively) than B-type analogues (9.2 and 3.6%, respectively). Wild lowbush cranberry exhibited a higher percentage of B-type dimers (16.5%) and trimers (12.8%) than A-type analogues (7.8 and 2.6%, respectively). Comparing wild bog blueberry to commercial lowbush blueberry, the former accumulated higher percentages of A-type dimers (13.7%) and trimers (11.7%) than the latter (2.0% and under the limit of detection, respectively). Among all the berries, commercial lowbush blueberry contained the highest percentage of polymeric proanthocyanidins (25.1%) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Normal phase HPLC-FLD chromatograms for proanthocyanidins (excitation 230 nm, emission 320 nm) in crude extracts of commercial cranberry (V. macrocarpon) and wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry (V. vitis-idaea).

Figure 4.

Normal phase HPLC-FLD chromatograms for proanthocyanidins (excitation 230 nm, emission 320 nm) in crude extracts of commercial lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium) and wild Alaskan bog blueberry (V. uliginosum).

Table 3.

Proanthocyanidin Composition in Wild Alaskan and Commercial Vaccinium Species Measured using Normal Phase HPLC and Fluorescence Detection, Excitation and Emission at 230 and 320 nm, respectively.

| % of total Proanthocyanidins |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proanthocyanidin | Cranberry (V. macrocarpon) | Lowbush Cranberrya (V. vitis-idaea) | Lowbush Blueberry (V. angustifolium) | Bog Blueberrya (V. uliginosum) |

| Monomers | 21.8 | 32.4 | 32.4 | 28.6 |

| Dimers A-type | 23.2 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 13.7 |

| Dimers B-type | 9.2 | 16.5 | 18.4 | 13.4 |

| Trimers A-type | 12.1 | 2.6 | ND | 11.7 |

| Trimers B-type | 3.6 | 12.8 | 8.2 | 7.1 |

| Tetramers | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 5.9 |

| Pentamers-heptamers | 4.6 | 10.8 | 6.8 | 3.4 |

| Polymers > 8 units | 18.8 | 9.8 | 25.1 | 15.2 |

Wild species collected from Alaska.

Phenolic Profile of Berries by LC-ESI-TOF-MSn

Based on extracted ion chromatogram (EIC), catechin predominated in wild lowbush cranberry, while epicatechin predominated in commercial cranberry and Alaskan bog blueberry. Procyanidin-A2 was prominent in commercial cranberry (Tables 3 & 4). Procyanidin-B1 was prominent in wild lowbush cranberry and commercial lowbush blueberry, while procyanidin B2 was present in commercial cranberry, lowbush and bog blueberries but weak in wild lowbush cranberry (Table 4). Procyanidin A-type trimers were highly detected in all berries except commercial lowbush blueberry which showed very weak signal. Chlorogenic acid was very prominent in commercial lowbush blueberry compared to the three other berries. Commercial cranberry contained quercetin, myricetin, syringetin and laricitrin glycosides, while wild lowbush cranberry was deficient in the last two flavonol glycosides. Commercial lowbush blueberry displayed quercetin, myricetin and syringetin glycosides with no laricitrin, compared to wild bog blueberry which contained the four flavonol glycosides. Additional results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proanthocyanidin Oligomers, Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids in Wild Alaskan and Commercial Vaccinium Species Identified by LC-ESI-MSn in the Negative Ion Mode.

| Compound | MS [M-1]−m/z | MS/MS m/z | UV λ (nm) | Rt min | Cranberry | Lowbush Cranberry a | Lowbush Blueberry | Bog Blueberrya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin | 289 | 245, 203 | 278 | 10.58 | Dweak | D | D | Dweak |

| Epicatechin | 289 | 245, 203 | 278 | 17.68 | D | Dweak | D | D |

| Procyanidin B1 | 577 | 407, 289 | 233, 278 | 9.50 | Dweak | D | D | Dweak |

| Procyanidin B2 | 577 | 407, 289 | 243, 278 | 13.60 | D | Dweak | D | D |

| Procyanidin A2 | 575 | 289 | 232, 278 | 23.00 | D | D | Dweak | D |

| Dimer A-type | 575 | 289 | 233, 278 | 19.90 | Dweak | D | Dweak | Dweak |

| Trimer B-type | 865 | 407 | 240, 277 | multiple peaks | D | D | D | D |

| Trimer A-type | 863 | 575, 423, | 241, 241 | multiple peaks | D | D | Dweak | D |

| Chlorogenic acid | 353 | - | 241, 325 | 12.84 | Dweak | Dweak | D | ND |

| Feruloylquinic acid | 267 | - | 322 | 23.26 | ND | ND | D | ND |

| Malonylcaffeoylquinic acid | 439 | 395.411 | 281 | 17.47 | D | ND | ND | ND |

| Quercetin | 301 | 229.041 | 268, 355 | 25.36 | D | D | D | D |

| Quercetin-3-rut | 609 | 463, 301 | 255, 355 | 25.30 | D | D | D | D |

| Quercetin-3-gal/glc | 463 | 301.03 | 254, 353 | 24.30 | D | D | D | D |

| Quercetin-3-arab | 433 | 301 | 256, 356 | 24.45 | D | D | D | D |

| Quercetin-3-acetoylrha | 489 | 447, 301 | 253, 353 | 25.34 | ND | ND | D | ND |

| Myricetin-3-gal/glu | 479 | 316, 271 | 260, 359 | 20.30, 23.60 | D | D | D | D |

| Myricetin-3-ara | 449 | 316 | 358 | 24.04 | D | ND | ND | D |

| Syringetin-3-O-glu | 507 | 344, 301 | 252, 353 | 24.90 | D | ND | D | D |

| Syringetin-ara | 477 | 344 | 245, 354 | 25.26 | D | ND | D | D |

| Laricitrin glu | 493 | 331 | 260, 360 | 24.04 | D | ND | ND | D |

| laricitrin ara | 463 | 331 | 254, 353 | 24.27 | Dweak | ND | ND | D |

Wild species collected from Alaska. D: detected, ND: not detected

Antioxidant Capacity

The relative antioxidant capacity as measured by DPPH, ABTS and FRAP assays mirrors the polyphenolic content of the investigated berries. Table 1 shows that wild lowbush cranberry had the highest radical scavenging activity in the three antioxidant capacity assays performed here (51.3 ± 2.2 and 69.3 ± 2.2 μM TE/g FW for DPPH and ABTS assays, respectively, and 122.2 ± 4.6 μM Fe+/g for FRAP assay). DPPH, APTS and FRAP assay results correlated well with the total phenolic content of the four investigated berries (R2 = 0.98, 0.99 and 0.997, respectively). A previous study on the antioxidant capacity of Alaskan wild berries utilizing H-ORACFL assay indicated that lowbush cranberry collected from interior and south-central Alaska had about 2.5 fold the activity as wild bog blueberry from same regions.32

A clean-up procedure was conducted on the crude extract, using C18 RP-SPE cartridge (Supelco), to remove sugars, pectins and lipophilic material, and to concentrate polyphenolic compounds. Anthocyanins were more concentrated in the commercial lowbush blueberry polyphenol-rich (PPR) fraction (193.1 mg/g), while PAC were highest in wild lowbush cranberry PPR-fraction (215.6 mg/g). The PPR contained an average of 30 fold the concentrations of TP in the crude extracts (See Table 5 for concentrations of ANC, PAC and TP in crude and PPR extracts). The PPR was tested alongside with the dried crude extract for anti-inflammatory activity.

Table 5.

Polyphenol Content of Crude and Polyphenol-Rich Fractions (mg/g) used in the Anti-inflammatory Activity Assay.

| Berry Extract | Crude Extract mg/g |

Polyphenol-Rich Fraction mg/g |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCa | PACb | TPc | ANCa | PACb | TPc | |

| Cranberry (V. macrocarpon) | 4.7C | 8.6B | 22.7C | 52.1C | 96.3BC | 905 |

| Lowbush Cranberryd (V. vitis-idaea) | 12.6B | 17.6A | 39.3A | 68.2C | 215.6A | 1030A |

| Lowbush Blueberry (V.angustifolium) | 14.6A | 5.5C | 28.5B | 193.1A | 103.3B | 883 |

| Bog Blueberryd (V. uliginosum) | 13.8AB | 5.5C | 32.7B | 156.9B | 69.3C | 723B |

ANC: anthocyanins, quantified by pH differential assay as cyanidin-3-O-glucoside;

PAC: proanthocyanidins, quantified by DMAC assay as procyanidin A2.

TP: total phenolics, quantified by Folin Ciocalteu assay as gallic acid equivalent; Means with different letters within the same column are significantly different at p < 0.05.

Wild species collected from Alaska.

Anti-inflammatory Assay

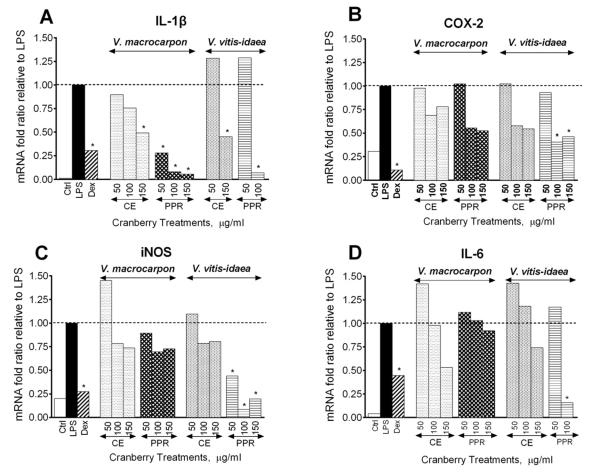

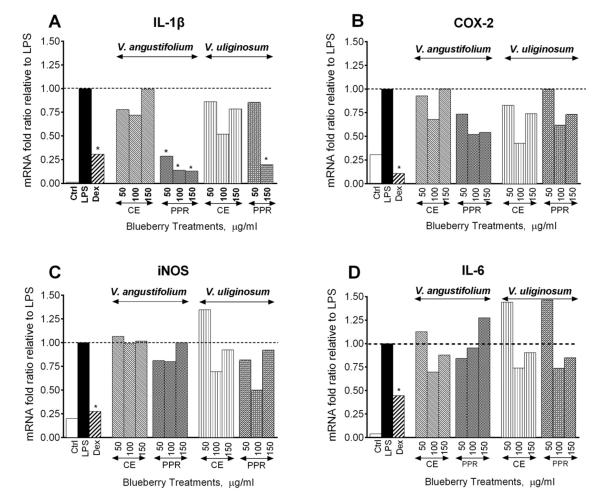

Many studies have suggested that exposure of mammalian cells to the main component of the outer membrane of the gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), can lead to release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and in turn activate inflammatory cascades including cytokines, lipid mediators and adhesion molecules such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These four well-known genetic biomarkers involved in the acute-phase response, inflammatory response, and humoral immune responses were investigated in vitro in the LPS-stimulated murine RAW 264.7 macrophage model. The in vitro experiments were designed to quantify the relative amount of transcripts for target genes within the total RNA in individual cell batches undergoing dose-dependent treatments (50, 100 and 150 μg/mL) with four CE and four PPR fractions. For each assay, three control sets were monitored. The negative control (no LPS treatment) maintained a constant amount of transcripts for all constitutively expressed genes and served as a reference baseline; the induction control (treated with LPS) showed the maximum up-regulation of the marker genes; and the positive control (treated with LPS and Dex) served as a reference for the effectiveness of the assay31. Since non-cytotoxic doses were predetermined by the MTT assay (data not shown), the observed changes in gene expression (genetic down-regulation) were not due to cell death.

Based on gene expression results, wild lowbush cranberry exhibited a potent anti-inflammatory activity in the macrophage cell culture based on a 2-fold or higher change in biomarker gene expression relative to the LPS-stimulated controls (Figures 5 and 6). In some instances, 10-fold reduction was observed in pro-inflammatory gene expression similar to or exceeding that of the positive control (Fig. 5A and 6A). PPR fractions of cranberry and lowbush blueberry effectively inhibited LPS-elicited induction of pro-inflammatory inducible cytokine IL-1β and two enzyme coding genes cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox2) and nitric oxide synthase (Figure 5B and 5C).

Figure 5.

Anti-inflammatory bioactivity of wild Alaskan and commercial Vaccinium crude extracts (CE) and polyphenol-rich fractions (PPR). Effects on the expression of the inflammatory biomarker genes in the LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages at 50, 100 and 150 μg/mL. Genes involved in the acute-phase response, inflammatory response, and humoral immune responses are represented: IL-1β assay (A), COX-2 assay (B), iNOS assay (C), IL-6 assay (D). Changes in gene expression were measured by comparing mRNA quantity relative to LPS. A value of less than 1.0 indicates transcriptional down-regulation (inhibition of gene expression) compared with LPS, which shows maximum genetic induction (1.0). Therefore, lower values indicate greater anti-inflammatory activity. Ctrl: cells treatment with vehicle only; Dex:dexamethasone at 10 μM used as positive control; C: commercial cranberry (V. macrocarpon) and W: wild lowbush cranberry (V. vitis-idaea).

Figure 6.

Anti-inflammatory bioactivity of wild Alaskan and commercial Vaccinium crude extracts (CE) and polyphenol-rich fractions (PPR). Effects on the expression of the inflammatory biomarker genes in the LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages at 50, 100 and 150 μg/mL. Genes involved in the acute-phase response, inflammatory response, and humoral immune responses are represented: IL-1β assay (A), COX-2 assay (B), iNOS assay (C), IL-6 assay (D). Changes in gene expression were measured by comparing mRNA quantity relative to LPS. A value of less than 1.0 indicates transcriptional down-regulation (inhibition of gene expression) compared with LPS, which shows maximum genetic induction (1.0). Ctrl: cells treatment with vehicle only; Dex: dexamethasone at 10 μM used as positive control; C: commercial blueberry (V. angustifolium) and W: wild bog blueberry (V. uliginosum).

Determination of pharmacologically-relevant and attainable doses for polyphenol-rich cranberry extracts in vivo will be an important next step towards developing novel preventive or clinical applications based on cranberry supplementation. Cranberry polyphenols are a complex mixture comprised of monomeric catechins, epicatechins, polymeric proanthocyanidins (with and without additional substitutions), and multiple anthocyanins (Tables 1 and 2). While anthocyanins are known for their low bioavailability, monomeric proanthocyanidins from fruits have been known to reach systemic circulation at the level of 50–80 μg/ml of plasma,33 which is comparable to the low-and mid-level doses used in this study. It is therefore likely that the in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of wild lowbush33 cranberry will be observed in vivo in circulating macrophages, and especially in resident intestinal macrophages that receive higher exposure to dietary polyphenols.34 All PPR fractions were highly enriched with ANC, PAC and TP, with the Alaskan lowbush cranberry showing the highest concentration of PAC (215.6 mg/g, Table 5). Lowbush blueberry PPR extract contained the highest ANC content among all berries, and higher levels of PAC compared to bog blueberry. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the berries is likely to be conditioned by the combination of flavonoid phytochemicals contained in the extracts, as has been noted in previous research35.

In summary, wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry and commercial American cranberry are both rich in PAC comprising about 45 and 38% of TP, respectively. The PAC content in wild lowbush cranberry was more than two fold higher than that in commercial cranberry. Compositional analyses indicated that commercial cranberry accumulates a richer concentration of procyanidin A-type dimers and trimers, while wild lowbush cranberry accumulates predominantly B-type dimers and trimers (>2x that of A-type). Wild Alaskan lowbush cranberry is characterized by high levels of the flavan-ol catechin (32.4% of proanthocyanidin content), compared to commercial cranberry where epicatechins comprise most of the monomer content (21.8%). Cranberry procyanidin A-type are known to inhibit the attachment of uropathogenic Escherichia coli to uroepithelial and vaginal cells,36 whereas wild lowbush cranberry has not been well evaluated for anti-adhesion capacity. Alaskan bog blueberry demonstrated higher levels of all phenolic groups investigated and higher antioxidant capacity than commercial lowbush blueberry. Bog blueberry lacks acylated anthocyanins, but contains higher levels of procyanidin A-type than lowbush blueberry. Investigations on acylated anthocyanins indicated that they may be less easily absorbed/less bioavailable than the non-acylated forms, a phenomenon which has been linked to their greater hydrophobicity.37,38 Thus, compositional differences between berry sources may impact on their biological activities. Alaskan wild berries are rich sources of antioxidants, based on their polyphenolic content and antioxidant capacity. Although wild berries in Alaska have limited accessibility, distribution and availability, and could not compete in commercial markets with cultivated berries, the enhanced accumulation of heath-beneficial wild berry constituents may represent a novel opportunity for development of Alaskan berries as a potential new niche market commodity; an American-grown specialty functional food to compete in the same market as several other exotic berry species currently in vogue.39

Acknowledgments

Funding This work is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM103395 at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and UNC General Administration funding. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai Q, Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Jackson JC, Larson EB. Fruit and vegetable juices and Alzheimer's disease: the Kame Project. Am. J. Med. 2006;119:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshipura KJ, Ascherio A, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA. 1999;282:1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.13.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He X, Liu RH. Cranberry phytochemicals: isolation, structure elucidation, and their antiproliferative and antioxidant activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:7069–7074. doi: 10.1021/jf061058l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirico TL, Omaye S. Additive or synergetic effects of phenolic compounds on human low density lipoprotein oxidation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006;44:510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duthie GG, Gardner PT, Kyle JA. Plant polyphenols: are they the new magic bullet? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003;62:599–603. doi: 10.1079/PNS2003275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan M, Lai C, Ho C. Anti-inflammatory activity of natural dietary flavonoids. Food Funct. 2010;1:15–31. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanek S, Butcher B. Alaska Cooperative Extension Publ. FNH-00120. 1998. Collecting and using Alaska's wild berries and other wild products. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellogg J, Wang J, Flint C, Ribnicky D, Kuhn P, De Mejia EG, Raskin I, Lila MA. Alaskan wild berry resources and human health under the cloud of climate change. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:3884–3900. doi: 10.1021/jf902693r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeram N, Adams LS, Hardy ML, Heber D. Total cranberry extract versus its phytochemical constituents: Antiproliferative and synergistic effects against human tumor cell lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:2512–2517. doi: 10.1021/jf0352778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard LR, Clark JR, Brownmiller C. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content in blueberries as affected by genotype and growing season. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003;83:1238–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lila MA. The nature-versus-nurture debate on bioactive phytochemicals: the genome versus terroir. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;86:2510–2515. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ek S, Kartimo H, Mattila S, Tolonen A. Characterization of phenolic compounds from lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:9834–9842. doi: 10.1021/jf0623687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lätti AK, Jaakola L, Riihinen KR, Kainulainen PS. Anthocyanin and flavonol variation in bog bilberries (Vaccinium uliginosum L.) in Finland. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:427–433. doi: 10.1021/jf903033m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Durst RW, Wrolstad RE. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. AOAC International. 2005;88:1269–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prior RL, Fan E, Ji H, Howell A, Nio C, Payne MJ, Reed J. Multi-laboratory validation of a standard method for quantifying proanthocyanidins in cranberry powders. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010;90:1473–1478. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grace MH, Guzman I, Roopchand DE, Moskal K, Cheng DM, Pogrebnyak N, Raskin I, Howell A, Lila MA. Stable binding of alternative protein-enriched food matrices with concentrated cranberry bioflavonoids for functional food applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:6856–6864. doi: 10.1021/jf401627m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grace MH, Ribnicky DM, Kuhun P, Poulev A, Logendra S, Yousef GG, Raskin I, Lila MA. Hypoglygemic activity of a novel anthocyanin-rich formulation from lowbush blueberry, Vaccinium angustifolium Aiton. Phytomed. 2009;16:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace TC, Giusti MM. Extraction and normal-phase HPLC-fluorescence-electrospray MS characterization and quantification of procyanidins in cranberry extracts. J. Food Sci. 2010;75:C690–C696. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truong VD, McFeeters RF, Thompson RT, Dean LL, Shofran B. Phenolic acid content and composition in leaves and roots of common commercial sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) cultivars in the United States. J. Food Sci. 2007;72:C343–C349. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS. radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szeto YT, Tomlinson B, Benzie IFF. Total antioxidant and ascorbic acid content of fresh fruits and vegetables: implications for dietary planning and food preservation. British J. Nut. 2002;87:55–59. doi: 10.1079/BJN2001483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlen Y, McNair A, Perseguers S, Mazza C, Mermod N. Statistical significance of quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng W, Wang SY. Oxygen radical absorbing capacity of phenolics in blueberries, cranberries, chokeberries, and lingonberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:502–509. doi: 10.1021/jf020728u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kylli P, Nohynek L, Puupponen-Pimiä R, Westerlund-Wikström B, Leppänen T, Welling J, Moilanen E, Heinonen M. Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and European cranberry (Vaccinium microcarpon) proanthocyanidins: isolation, identification, and bioactivities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:3373–3384. doi: 10.1021/jf104621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson ØM. Anthocyanins in fruits of Vaccinium uliginosum L. (bog whortleberry) J. Food Sci. 1987;52:665–666. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grace MH, Massey AR, Mbeunkui F, Yousef GG, Lila MA. Comparison of health-relevant flavonoids in commonly consumed cranberry products. J. Food Sci. 2012;77:H176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Määttä-Riihinen KR, Kamal-Eldin A, Mattila PH, González-Paramás AM, Riitta, T. AR. Distribution and contents of phenolic compounds in eighteen Scandinavian berry species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:4477–4486. doi: 10.1021/jf049595y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinelli EM, Baj A, Bombardelli E. Computer-aided evaluation of liquid-chromatographic profiles for anthocyanins in Vaccinium myrtillus fruits. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1986;191:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leiner, R. H, Holloway PS, Neal DB. Antioxidant capacity and quercetin levels in Alaska wild berries. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2006;6:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal C, Singh RP, Agarwal R. Grape seed extract induces apoptotic death of human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells via caspases activation accompanied by dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential and cytochrome c release. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1869–1876. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magrone T, Jirillo E. The interplay between the gut immune system and microbiota in health and disease: nutraceutical intervention for restoring intestinal homeostasis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013;19:1329–1342. doi: 10.2174/138161213804805793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuevas-Rodriguez EO, Dia VP, Yousef GG, Garcia-Saucedo PA, Lopez-Medina J, Paredes-Lopez O, Gonzalez de Mejia E, Lila MA. Inhibition of pro-inflammatory responses and antioxidant capacity of Mexican blackberry (Rubus spp.) extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:9542–9548. doi: 10.1021/jf102590p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howell AB, Reed JD, Krueger CG, Winterbottom R, Cunningham DG, Leahy M. A-type cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenic bacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2281–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charron CS, Clevidence BA, Britz SJ, Novotny JA. effect of dose size on bioavailability of acylated and nonacylated anthocyanins from red cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. Var. capitata) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:5354–5362. doi: 10.1021/jf0710736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charron CS, Kurilich AC, Clevidence BA, Simon PW, Harrison DJ, Britz SJ, Baer DJ, Novotny JA. Bioavailability of anthocyanins from purple carrot juice: effects of acylation and plant matrix. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:1226–1230. doi: 10.1021/jf802988s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kellog J, Higgs C, Lila MA. Prospects for commercialization of an Alaskan native wild resource as a commodity crop. J. Entrepreneurship. 2011;20:77–101. [Google Scholar]