Abstract

Aims: The reaction of nitric oxide and nitrite-derived species with polyunsaturated fatty acids yields electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives (NO2-FA), which display anti-inflammatory properties. Given that the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO, ALOX5) possesses critical nucleophilic amino acids, which are potentially sensitive to electrophilic modifications, we determined the consequences of NO2-FA on 5-LO activity in vitro and on 5-LO-mediated inflammation in vivo. Results: Stimulation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) with nitro-oleic (NO2-OA) or nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA) (but not the parent lipids) resulted in the concentration-dependent and irreversible inhibition of 5-LO activity. Similar effects were observed in cell lysates and using the recombinant human protein, indicating a direct reaction with 5-LO. NO2-FAs did not affect the activity of the platelet-type 12-LO (ALOX12) or 15-LO-1 (ALOX15) in intact cells or the recombinant protein. The NO2-FA-induced inhibition of 5-LO was attributed to the alkylation of Cys418, and the exchange of Cys418 to serine rendered 5-LO insensitive to NO2-FA. In vivo, the systemic administration of NO2-OA to mice decreased neutrophil and monocyte mobilization in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), attenuated the formation of the 5-LO product 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE), and inhibited lung injury. The administration of NO2-OA to 5-LO knockout mice had no effect on LPS-induced neutrophil or monocyte mobilization as well as on lung injury. Innovation: Prophylactic administration of NO2-OA to septic mice inhibits inflammation and promotes its resolution by interfering in 5-LO-mediated inflammatory processes. Conclusion: NO2-FAs directly and irreversibly inhibit 5-LO and attenuate downstream acute inflammatory responses. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 2667–2680.

Introduction

The endogenous redox reactions of nitric oxide (NO) and nitrite (NO2−) yield the nitrating species nitrogen dioxide (NO2). A key biological reaction of .NO2 is the nitration of polyunsaturated fatty acids to generate electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives (NO2-FA) such as nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA) and nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA, Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). NO2-FAs have been detected in healthy human plasma and urine in nano- to micromolar concentrations (1, 21, 35) and display anti-inflammatory properties in vitro and in vivo. Indeed, NO2-OA limits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced multi-organ dysfunction, an effect that is paralleled by a decrease in the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, the inducible NO synthase, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (38). NO2-FAs also inhibit ischemic tissue injury and neointima formation after wire-induced injury of the femoral artery (6).

Innovation.

Nitro-fatty acids (NO2-FAs); such as nitro-oleic and nitro-linoleic acid, are generated by inflammation-associated free radical reactions and have been implicated in the resolution of inflammation. In this study, we show that the anti-inflammatory actions of nitro-oleic acid can be attributed to the inhibition of the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) and are lacking in 5-LO knockout mice. The NO2-FA-induced alkylation of Cys418 in 5-LO rather than a more general effect on nuclear factor κB signaling was found to be responsible for these effects. These findings point to an important role of NO2-FAs in limiting inflammation via the post-translational modification of the 5-LO.

The nitration of fatty acids renders the β-carbon electrophilic and reactive with nucleophilic amino acids, including the cysteine thiol, and, to a lesser extent, the histidine imidazole and ɛ-amino of lysine, forming reversible adducts (4, 35). In target tissues, NO2-FAs react with susceptible nucleophilic amino acids and post-translationally modify protein structure, function, and/or subcellular distribution. To date, NO2-FAs have been reported to inhibit xanthine oxidase (20) and nuclear factor κB (NFκB)-regulated gene expression, with the latter being the consequence of adduction of a critical cysteine in the p65 subunit (8). Simultaneously, NO2-FAs are partial agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ (23, 34), and Nrf2-dependent phase 2 gene expression can be activated by the NO2-FA-mediated adduction of select cysteine residues in the Nrf2 regulatory protein, Keap1 (19).

Inflammatory responses are induced, in part, by pro-inflammatory COX-2-derived prostaglandins (PG) and lipoxygenase (LO)-dependent leukotriene (LT) synthesis (24). Eicosanoids such as PGE2 and LTB4 are potent modulators of inflammation, regulating leukocyte recruitment and activation and thus increasing vascular permeability and edema formation (10, 25). Leukotriene synthesis involves the phospholipase A2-dependent hydrolysis of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, which is then oxidized by 5-LO to the lipid mediators 5-hydroperoxy eicosatetraenoic acid (5-H(P)ETE) and LTA4, yielding 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), LTB4, and LTC4. Since 5-LO possesses catalytically important nucleophilic amino acids that may be reactive with lipid electrophiles (9), we hypothesized that the reaction of 5-LO with NO2-FAs might lead to enzyme inhibition and account for some of the anti-inflammatory actions of NO2-FAs.

Results

Effect of OA, NO2-OA, LA, and NO2-LA on 5-LO activity

To determine the impact of NO2-FA on 5-LO activity, enzyme activity was assessed both in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) as well as using the recombinant enzyme. After stimulation by inflammatory mediators, the 5-LO is activated by increased intracellular Ca2+ and MAP kinase-dependent phosphorylation, which results in the translocation of the enzyme to the nuclear membrane (30). In intact human PMNL, the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 stimulated 5-LO product formation (183±12 ng/106 cells). NO2-LA and NO2-OA inhibited 5-LO product formation in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 values of 1.9±0.5 and 0.9±0.2 μM, respectively, whereas oleic acid (OA) and linoleic acid (LA) had no significant effect (Fig. 1A and Table 1). To exclude the possibility that NO2-OA or NO2-LA inhibit phospholipase A2 rather than the 5-LO directly, experiments in intact PMNL were performed in which low (2 μM) or high concentrations (20 μM) of arachidonic acid were exogenously added. NO2-OA as well as NO2-LA inhibited 5-LO product formation under both conditions (Fig. 1B, C and Table 1). The 5-LO can also be activated by other mechanisms; therefore, the consequences of NO2-FAs on 5-LO activation by hyperosmotic shock (0.3 M NaCl), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine (GM-CSF/fMLP), and exposure to sodium arsenite (39) were assessed. Both of the NO2-FAs tested, but not the corresponding parent lipids, significantly attenuated 5-LO product synthesis by intact human PMNL treated with each of these stimuli (Fig. 1D, E and Supplementary Fig. S2A and Table 1). Moreover, the stimulation of PMNL homogenates and purified cytosolic fractions with NO2-FAs inhibited 5-LO activity, while the native fatty acids did not exhibit any effect (Supplementary Fig. S2B, C and Table 1). The incubation of recombinant human 5-LO with NO2-LA or NO2-OA concentration-dependently inhibited activity (Fig. 2A and Table 1) and was unaffected by excess arachidonic acid (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the effects of OA, LA, NO2-OA, and NO2-LA on the activity of 5-LO in intact human PMNL. (A–C) Concentration-response curves of human PMNL stimulated with A23187 (2.5 μM) in the absence of arachidonic acid (AA, A) and in the presence of 2 μM (B) as well as 20 μM AA (C). (D and E) Concentration-response curve of human PMNL stimulated with NaCl (300 mM, D) or fMLP (100 nM) after GM-CSF (1 nM) priming (E). The graphs summarize data from three to six independent experiments each using a different batch of human PMNL/eosinophil preparations; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus OA. fMLP, N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; LA, linoleic acid; LO, lipoxygenase; OA, oleic acid; PMNL, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Table 1.

IC50 Values (μM) of 5-LO Inhibition

| NO2-OA | NO2-LA | |

|---|---|---|

| Intact PMNL | ||

| A23187−AA | 0.9±0.2a | 1.9±0.5a |

| A23187+AA (2 μM) | 3.1±0.6a | 7.8±1.8a |

| A23187+AA (20 μM) | 6.4±1.3a | 7.6±0.5a |

| GM-CSF/fMLP | 15.2±9.2a | 8.8±0.6a |

| NaCl | 8.0±3.0b | 15.1±3.8a |

| Na arsenite | 9.0±3.0a | 26.7±0.6a |

| PMNL homogenate | 2.6±0.5b | 0.3±0.2b |

| PMNL cytosol | 1.7±0.1a | 1.2±0.3a |

| Recombinant 5-LO | 0.3±0.06b | 0.004±0.002b |

Intact PMNL, PMNL homogenates, the corresponding cytosolic fraction (PMNL cytosol), or recombinant 5-LO were stimulated with LA, OA, NO2-LA, or NO2-OA and 5-LO activity was assayed after stimulation with a Ca2+-ionophore (A23187) in either the presence or absence of arachidonic acid (AA), GM-CSF/fMLP, NaCl, or Na arsenite. Product formation in homogenates, cytosolic preparations, and the recombinant 5-LO was stimulated with CaCl2 (2 mM). IC50 values for LA and OA stimulations are not shown, as those substances only exhibit weak inhibitory activities. Values represent mean±SEM from three to six independent experiments; ap<0.05, bp<0.01, versus the corresponding nonnitrated fatty acid.

fMLP, N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; LA, linoleic acid; LO, lipoxygenase; NO2-OA, nitro-oleic acid.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the effects of NO2-FAs and parent fatty acids on the 5-, 12-, and 15-LO-activity after stimulation in the recombinant system or intact human cells. (A) Concentration-response curve of recombinant human 5-LO in the presence of all fatty acids. (B) Comparison of the effects of increasing amounts of arachidonic acid (AA) on the NO2-FA-mediated 5-LO inhibition. Recombinant 5-LO was incubated with the indicated concentrations of AA in the presence of 5 μM OA, LA, NO2-OA, or NO2-LA and 5-LO metabolites were measured. (C, D) Effect of fatty acids on 12-HETE formation in human platelets (C) and 15-HETE formation in human eosinophils (D). (E) Reversibility of the effect of fatty acids (10 μM) on PMNL 5-LO activity. BW (BW4AC, 1 μM) and U73122 (10 μM) were used as positive controls for a reversible and irreversible inhibition, respectively. (F) Comparison of the effects of NO2-FAs (3 μM) on the wild-type (WT) enzyme and different 5-LO cysteine mutants. The enzyme activities were WT: 0.8±0.1 μmol·min−1·mg−1, C4: 0.8±0.1 μmol·min−1·mg−1, C159S: 0.7±0.1 μmol·min−1·mg−1, C300S: 0.8±0.2 μmol·min−1·mg−1, C416S: 0.5±0.1 μmol·min−1·mg−1, and C418S: 0.9±0.1 μmol·min−1·mg−1. (G) Consequence of NO2-FA stimulation on the iron content of WT and C418S 5-LO. Values were normalized to the iron content of the corresponding solvent-incubated enzyme. The graphs summarize data from three to six independent experiments each using a different batch of PMNL eosinophils, platelets or recombinant human 5-LO; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 versus corresponding non-nitrated fatty acid (A, B, G), wash out (E), or WT (F). NO2-FA, nitro-fatty acids; NO2-LA: nitro-linoleic acid; NO2-OA: nitro-oleic acid.

Given the structural homology of 5-, 12-, and 15-LO (13), the effects of both NO2-FAs on the activity of the platelet-type 12-LO (ALOX12) and 15-LO-1 (ALOX15) isoforms were also assessed. The 12-LO-dependent generation of 12-HETE by human platelets (Fig. 2C) and the 15-LO-1-dependent generation of 15-HETE in human eosinophils (Fig. 2D) were not inhibited by NO2-OA and NO2-LA at concentrations of approximately 30 μM. The arachidonic acid-induced formation of 12- and 15-HETE by purified recombinant murine platelet-type 12-LO or human 15-LO-1 was also not affected by NO2-OA or NO2-LA (Supplementary Fig. S2D, E).

Finally, to determine whether the NO2-FA-mediated inhibition of 5-LO was irreversible, PMNL were treated with NO2-OA, NO2-LA, the competitive 5-LO inhibitor BWA4C, or the irreversible inhibitor U73122 (17). While 5-LO product formation was restored by washing cells treated with BWA4C, there was no recovery of 5-LO activity in NO2-OA-, NO2-LA-, or U73122-treated cells (Fig. 2E). These data suggested that NO2-FAs directly and specifically inhibit 5-LO rather than interfering with an upstream activation pathway. For all further experiments, NO2-OA rather than NO2-LA was chosen solely because of more favorable pharmacokinetics, a simpler metabolite profile, and due to the fact that both NO2-FAs displayed similar inhibitory properties with regard to 5-LO (32, 37).

Mechanism of 5-LO inhibition by NO2-OA

The post-translational modification of susceptible nucleophilic amino-acid residues in 5-LO by NO2-OA was assessed using a combination of mutagenesis and proteomic studies. Incubation of human recombinant 5-LO with NO2-OA for 15 min resulted in the adduction of histidine residues His125, His360, His362, His367, His372, and His432 (Table 2). Importantly, not all of the catalytic site histidine residues were adducted under these conditions. No adduction of these residues was detected in samples treated with OA (Table 2). Moreover, the majority of the peptides covering His360, His362, His367, His372, and His432 were found in the alkylated state, as indicated by the decrease in the peak area of the nonalkylated peptide in samples treated with NO2-OA (Table 3).

Table 2.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of the 5-LO

| PSYTVTVATGSQWFAGTDDYIYLSLVGSAGCSEKHLLDKPFYNDFERAVDSYDVTVDEELGEIQLVRIEKRKYWLNDDWYLKYITLKTPHGDYIEFPCYRWITGDVEVVLRDGRAKLARDDQIH125ILKQHRRKELETRQKQYRWMEWNPGFPLSIDAKCHKDLPRDIQFDSEKGVDFVLNYSKAMENLFINRFMHMFQSSWNDFADFEKIFVKISNTISERVMNHWQEDLMFGYQFLNGCNPVLIRRCTELPEKLPVTTEMVECSLERQLSLEQEVQQGNIFIVDFELLDGIDANKTDPCTLQFLAAPICLLYKLANKIVPIAIQLNQIPGDENPIFLPSDAKYDWLLAKIWVRSSDFH360VH362QTITH367LLRTH372LVSEVFGIAMYRQLPAVHPIFKLLVAHVRFTIAINTKAREQLIC416EC418GLFDKANATGGGGH432VQMVQRAMKDLTYASLCFPEAIKARGMESKEDIPYYFYRDDGLLVWEAIRTFTAEVVDIYYEGDQVVEEDPELQDFVNDVYVYGMRGRKSSGFPKSVKSREQLSEYLTVVIFTASAQHAAVNFGQYDWCSWIPNAPPTMRAPPPTAKGVVTIEQIVDTLPDRGRSCWHLGAVWALSQFQENELFLGMYPEEHFIEKPVKEAMARFRKNLEAIVSVIAERNKKKQLPYYYLSPDRIPNSVAI | ||

|---|---|---|

| Precursor mass ion [M+H]+(Da) | ||

| Peptide sequence | Native (Carbamidomethylated) | NO2-OA alkylated |

| DDQIH125ILK | 981.54 | 1308.78 |

| SSDFH360VH362QTITH367LLR | 1790.92 | 2118.16 |

| TH372LVSEVFGIAMYR | 1622.83 | 1950.07 |

| ANATGGGGH432VQMVQR | 1482.72 | 1809.96 |

| EQLIC416EC418GLFDK | 1511.69 | 1781.92 |

Recombinant human 5-LO was incubated with OA and NO2-OA (both 5 μM), and alkylation of protein was analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The underlined peptides of the 5-LO sequence represent the identified alkylated peptides identified. Modified residues identified by collision-induced dissociation spectra analysis are numbered and marked in bold. The table shows the precursor mass ion [M+H]+(Da) of the native and NO2-OA-alkylated 5-LO peptides and the modified amino acid. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. Peptides detected with a 327.24 Da mass shift compared with the native precursor mass ion indicated an alkylation of NO2-OA. The peptide SSDFHVHQTITHLLR covering three histidines (His360, His362, and His367) was only recovered with a single alkylation.

Table 3.

Label-Free Quantification Results of Tryptic Peptides Containing Histidines 125, 360, 362, 367, and 432 and Cysteines 416 and 418

| Peptide sequence | CTL | NO2-OA | Peak area decrease (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDQIH125ILK | 2.01E+09±1.04E+08 | 1.37E+09±1.09E+08 | 32 |

| SSDFH360VH362QTITH367LLR | 1.43E+09±8.43E+08 | 1.52E+08±6.79E+07 | 89 |

| TH372LVSEVFGIAMYR | 1.64E+09±8.21E+07 | 5.75E+08±7.20E+07 | 65 |

| ANATGGGGH432VQMVQR | 6.78E+07±8.73E+06 | 2.71E+07±1.73E+06 | 60 |

| EQLIC416EC418GLFDK | 1.32E+09±2.25E+08 | 6.56E+08±1.12E+08 | 50 |

Recombinant human 5-LO was incubated with OA and NO2-OA (both 5 μM), and alkylation of protein was analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Peak areas of the corresponding nonalkylated peptide at the same retention time and charge state from controls and NO2-OA-treated samples were integrated and compared. For the same peptide motif, mean area values in the treated samples were decreased between 32% and 89%, suggesting that significant fractions of corresponding histidines or cysteines undergo alkylation. The table shows the mean area of the native peptides, and values represent mean±SEM from three to four independent experiments.

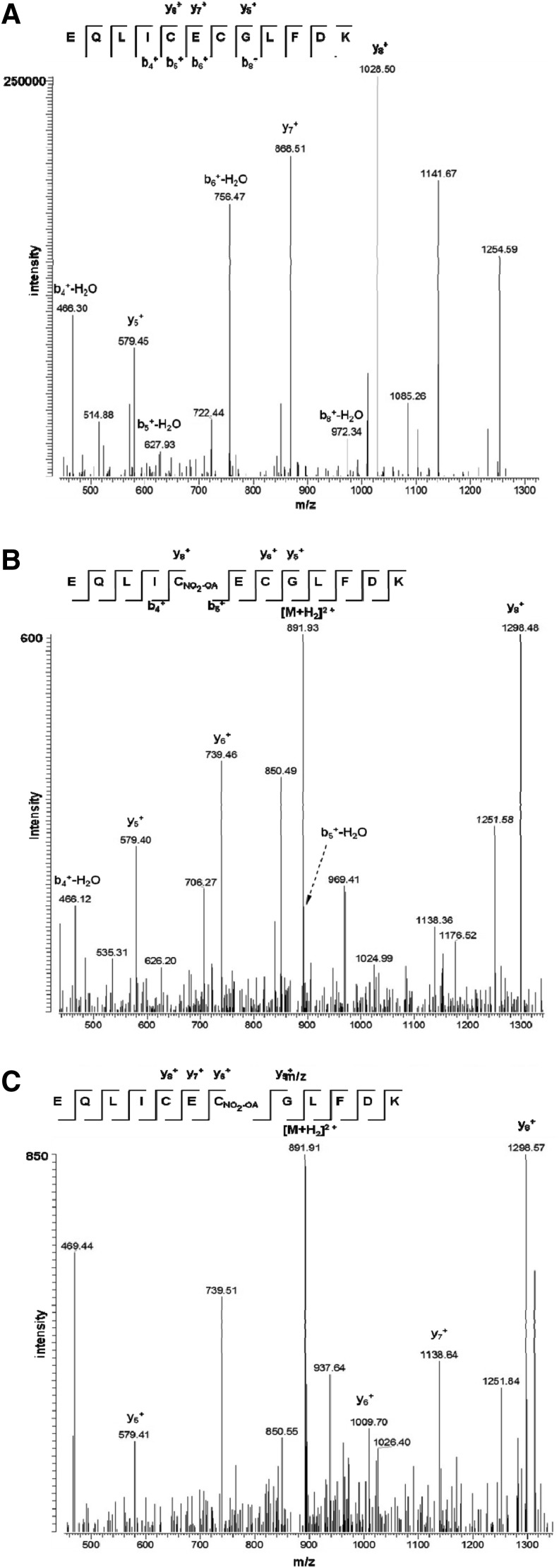

The histidine residues modified in the 5-LO are conserved in the human platelet-type 12-LO and 15-LO-1 enzymes that are resistant to NO2-FA inhibition, inferring that the adduction of histidine residues alone could not account for preferential inhibition of 5-LO by NO2-FA. Cysteines at positions 159, 300, 416, and 418 are, on the other hand, unique to 5-LO; they are also located at the solvent interface of the enzyme and critical for enzymatic activity (14). The 5-LO tryptic peptide containing Cys416 and Cys418 was alkylated after incubation with NO2-OA (Table 2), and mass spectrometric analysis revealed that both cysteine residues were modified (Fig. 3) with each hit detected on a different peptide. In addition, ∼50% of the recovered peptides that contained these residues were alkylated by NO2-OA (Table 3) The peptides containing residues Cys159 and Cys300 were not detectable by mass spectrometry (MS).

FIG. 3.

Collision-induced dissociation spectra identifying NO2-OA adducts on Cys416 and Cys418 in human 5-LO. Precursor ions of peptide EQLIC416EC418GLFDK alkylated by iodoacetamide with a mass of 1511.69 Da [M+H]+ or alkylated with NO2-OA at Cys416 or Cys418 with masses of 1781.92 Da [M+H]+ were isolated and fragmented by collision-induced dissociation in the linear ion trap. Generated product ions were evaluated for carbamidomethylation or NO2-OA adducts. (A) Collision-induced dissociation spectra of the native peptide mapping relevant b- and y-type fragment ions. Both cysteines are carbamido methylated and exhibit a 57.02 Da mass shift to the corresponding fragment ions b5, b6, and y7. (B) The fragment ions b5 and y8 showed a mass shift of 327.24 Da that indicated the adduction of NO2-OA at Cys416. (C) The fragment ions y6 and y7 exhibited a mass shift of 327.24 Da that indicated the adduction of NO2-OA at Cys418. Due to higher hydrophobicity, NO2-OA alkylated peptides elute 30 min later than native peptide. They also exhibit spectra of reduced intensity.

To better address the impact of Cys adduction on the inhibition of 5-LO catalysis by NO2-FAs, a 5-LO mutant was generated in which cysteine residues 159, 300, 416, and 418 were substituted with serine. This 4C mutant was resistant to inhibition by NO2-OA as well as by NO2-LA (Fig. 2F). Single mutation studies then identified Cys418 as the amino acid that defined NO2-FA sensitivity (Fig. 2F). 5-LO inhibition by BWA4C, which targets the catalytic iron, was unaffected by these specific Cys mutations.

The mutations of His367 and His372 were previously shown to release the nonheme iron from the catalytic domain of 5-LO (42). Hence, alklyation of these residues would be expected to reduce the iron content of the wild-type enzyme. To determine whether or not Cys418 is essential for the NO2-FA mediated alkylation of iron coordinating histidines, the iron content of the wild-type enzyme and the C418S 5-LO mutant was determined after incubation with NO2-OA or NO2-LA by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS). Incubation of the wild-type 5-LO, but not C418S 5-LO, with either NO2-OA or NO2-LA resulted in a 30% decrease in the iron content compared with the enzyme stimulated with the parent lipid (Fig. 2G). The iron content of the C418S 5-LO mutant was reduced by ∼30% compared with the wild-type enzyme under basal conditions (0.71±0.09 mol Fe·mol enzyme−1 for the wild-type vs. 0.49±0.13 mol Fe·mol enzyme−1 for the C418S 5-LO mutant) but was not further affected by NO2-FA.

Anti-inflammatory actions of NO2-OA

LO-derived LTB4 stimulates neutrophils and contributes to the inflammatory response (10). To determine whether the NO2-OA-mediated inhibition of 5-LO is pathophysiologically relevant, the effects of NO2-OA on LPS-induced 5-LO activation and neutrophil infiltration were studied in the mouse lung. LPS administration induced the mobilization of neutrophils and monocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B), inflammatory cell accumulation in the lung (Fig. 4A, B), and the development of moderate to severe lung injury (Fig. 4C). This was accompanied by increased plasma (Supplementary Fig. S3C, D) and pulmonary levels of the 5-LO products, LTB4 and 5-HETE (Fig. 4D, E). Treating mice with NO2-OA significantly attenuated neutrophil and monocyte numbers in the blood (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B) and lung tissue (Fig. 4A, B), as well as 5-LO product formation in the plasma (Supplementary Fig. S3C, D) and lung tissue (Fig. 4D, E). Similar effects were observed in animals treated with the 5-LO inhibitor zileuton. A histopathological analysis of the lungs showed that NO2-OA also attenuated LPS-induced lung injury compared with vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 4C). LPS-induced increases in 12-HETE were, however, not affected by NO2-OA (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Fig. S3E), but by zileuton—a phenomenon that may be explained by the known effect of zileuton on arachidonic acid release (31). Both NO2-FA and zileuton decreased PGE2 levels in the plasma (Supplementary Fig. S3F) and lungs (Fig. 4G) from LPS-treated mice without affecting the levels of any other PGs measured (Supplementary Fig. S4). These findings most likely reflect the attenuated mobilization of PGE2-producing leukocytes by NO2-FA.

FIG. 4.

Consequences of OA- and NO2-OA treatment on LPS-induced lung injury and cellular infiltration in wild-type mice. C57Bl6/J mice treated with vehicle (DMSO), OA, NO2-OA, or zileuton were challenged with solvent (sol, PBS) or LPS (20 mg/kg). After 16 h, lung and blood samples were taken for subsequent analysis. Quantification of infiltrating (A) neutrophils and (B) monocytes in the lung. (C) Representative hematoxylin- and eosin-stained lung sections of solvent and LPS-challenged mice treated with vehicle, OA, NO2-OA, or zileuton. The bar represents 100 μm. (D–G) Consequences of OA-, NO2-OA-, and zileuton treatment on LPS-induced (D) LTB4-, (E) 5-HETE (F) 12-HETE, and (G) PGE2 levels in lung tissue. The graphs summarize data from 3 to 8 mice/group; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 versus LPS+vehicle.

5-LO is required for the anti-inflammatory effects of NO2-OA

Given that NO2-OA and zileuton elicited comparable anti-inflammatory effects and attenuated neutrophil and monocyte mobilization as well as lung damage, responses were compared in wild-type and 5-LO−/− mice. Neutrophil and monocyte mobilization, as well as inflammatory cell infiltration into the lung were comparable in LPS-treated wild-type and 5-LO−/− mice (Fig. 5). However, although NO2-OA and zileuton attenuated all the measured aspects of inflammation in wild-type mice (see Fig. 4), they were ineffective in LPS-treated 5-LO−/− mice (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Consequences of OA- and NO2-OA treatment on LPS-induced lung injury and cellular infiltration in 5-LO-deficient mice (5-LO−/−). Wild-type (WT) and 5-LO−/− (−/−) treated with vehicle (veh, 50% DMSO), OA, or NO2-OA were challenged with solvent (sol) or LPS. After 16 h, lung and blood samples were taken for subsequent analysis. Quantification of infiltrating (A) neutrophils and (B) monocytes in the lung. (C) Representative hematoxylin- and eosin-stained lung sections of solvent- or LPS-challenged WT and 5-LO−/− mice. (D) Representative hematoxylin- and eosin-stained lung sections of solvent- or LPS-challenged 5-LO−/− mice treated with vehicle, OA, NO2-OA, or zileuton. The bar represents 100 μm. (E, F) Consequences of OA- and NO2-OA treatment on LPS-induced neutrophils (E) and monocyte mobilization (F) into blood of WT and 5-LO−/− mice. The graphs summarize data from 4 to 7 mice/group. *p<0.05, and ***p<0.001 versus WT+Sol, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, and ###p<0.001 versus 5-LO−/−+Sol.

The anti-inflammatory effects of NO2-FA have been linked to the adduction of these fatty acid species to NFκB (8, 34), PPAR-γ (33), and Keap1 (18). We, therefore, assessed whether or not NO2-FA administration altered the expression of typical NFκB-regulated genes.

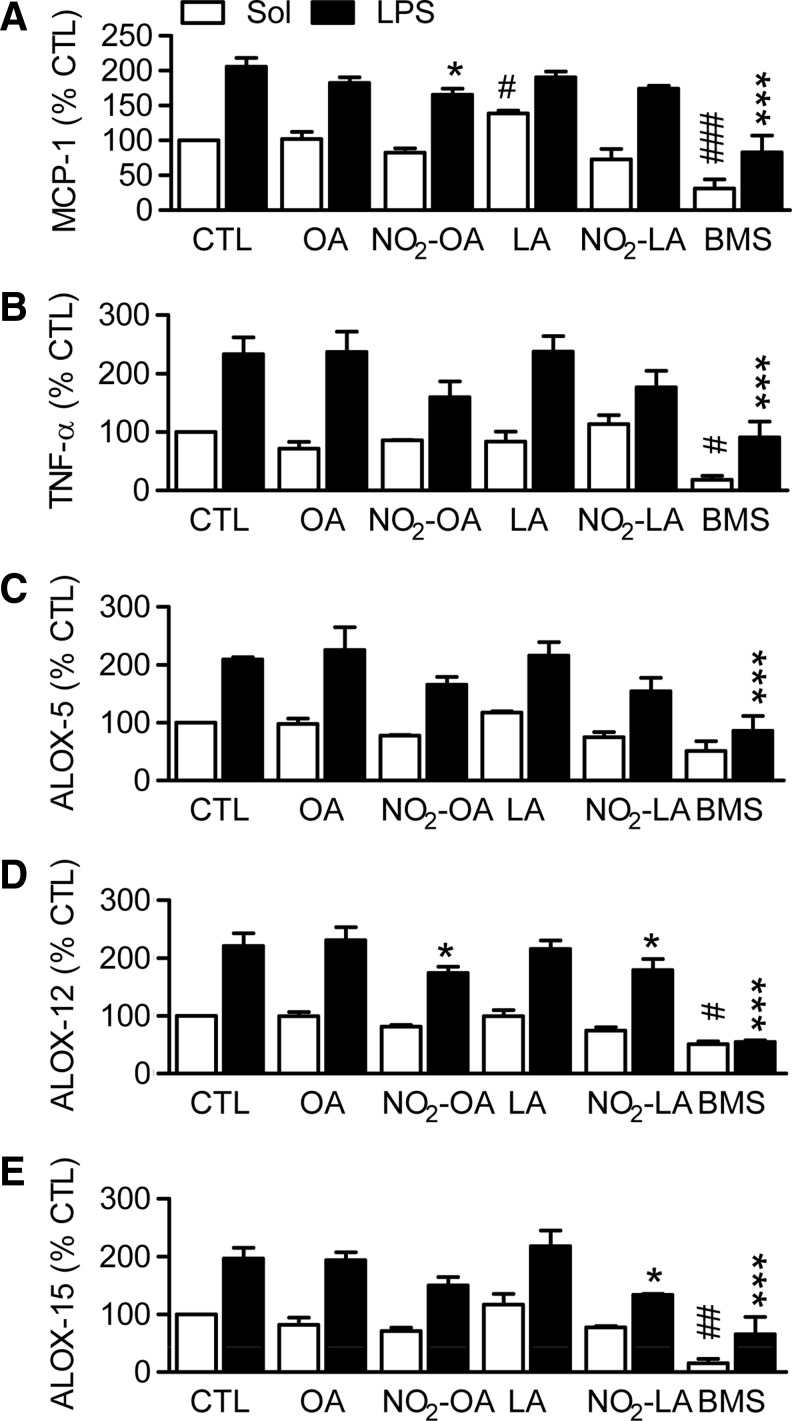

In human white blood cells (WBCs), LPS stimulated an increase in MCP-1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, ALOX5, ALOX12, and ALOX15 mRNA levels by approximately two-fold. These responses were unaffected by OA or LA, while NO2-OA and NO2-LA decreased expression by less than 25% (Fig. 6). The relatively small impact of NO2-OA and NO2-LA on the expression of these NFκB-related genes contrasted with the marked inhibition of gene expression observed in cells treated with an inhibitor of the IκB kinase (Fig. 6). Similarly, the administration of LPS to mice in vivo induced the expression of a series of NFκB-regulated genes and the Nrf2 target, heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) (Supplementary Fig. S5). NO2-OA failed to affect the expression of the majority of the genes studied but attenuated the expression of interleukin-6 and induced the expression of matrix metalloprotease 9 (MMP9), an effect also observed in zileuton-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S5).

FIG. 6.

Consequences of LA-, OA-, NO2-LA-, and NO2-OA treatment on the LPS-induced expression of TNF-α, MCP1, 5-, 12-, and 15-ALOX in human WBC. Freshly isolated human WBC were incubated with solvent (CTL), the indicated fatty acids (5 μM), or an inhibitor of the I(B kinase (BMS, 8 μM) for 8 h in the presence and absence of LPS (100 ng/ml) and qRT-PCR was performed. (A) TNF-α, (B) MCP-1, (C) ALOX-5, (D) ALOX-12, and (E) ALOX-15 mRNA expression. The graphs summarize data from three independent experiments each using a different cell donor; *p<0.05, and ***p<0.001 versus CTL+LPS; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, and ###p<0.001 versus CTL+Sol. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-α; WBC, white blood cell.

Finally, we addressed the possibility that NO2-FAs targeted the glutathione peroxidases that are known to suppress cellular 5-LO activity in neutrophils (16), B cells (37), and monocytes (33). However, treating Mono Mac 6 cells with NO2-OA had no significant effect on total cellular glutathione peroxidise (GPx) activity (data not shown). Thus, the anti-inflammatory effects of NO2-FAs can be attributed to the direct inhibition of 5-LO rather than to the direct inhibition of NFκB, the activation of Nrf2, or the activation of PPAR-γ, leading to the transrepression of NFκB.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the fatty acid nitroalkenes, NO2-OA, and NO2-LA inhibit the 5-LO without affecting the activity of the platelet-type 12-LO or 15-LO-1 isoforms. The NO2-FA-mediated inhibition of 5-LO was noncompetitive and could be attributed to the post-translational modification of the enzyme on Cys418. 5-LO inhibition was reproduced in a murine model of LPS-induced inflammation, where NO2-OA attenuated 5-LO but not 12-LO product formation. Simultaneously, NO2-OA largely prevented lung injury and systemic immune responses in wild-type animals but was ineffective in animals lacking 5-LO.

Reactive oxygen- and NO-derived species are produced during inflammation and promote the oxidation and nitration of biomolecules, including unsaturated fatty acids. Among the products of these reactions are an array of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl and nitroalkene derivatives of fatty acids. These substituents confer electrophilic properties that promote their reaction with susceptible nucleophilic amino-acid residues of proteins, resulting in altered function (22). This study focused on the possible interaction between NO2-FAs and LOs, as these enzymes mediate inflammation by generating H(P)ETEs, HETEs, and LTs. Of the three relevant LO enzymes studied (5-, 12-, and 15-LO), only the 5-LO possesses functionally relevant nucleophilic amino acids within the catalytic center and the solvent interface of the enzyme that are potentially sensitive to electrophilic attack (9). Indeed, NO2-OA and NO2-LA inhibited 5-LO activity in human PMNL, but not the human platelet-type 12-LO in platelets or the 15-LO-1 in human eosinophils. To determine the mechanisms underlying 5-LO inhibition, 5-LO product formation was assessed in intact human PMNL, cell lysates, and using a recombinant of human 5-LO. NO2-FAs inhibited 5-LO activity independently of the mode of enzyme activation and were equally effective toward intact cell preparations and recombinant 5-LO. The fact that increasing arachidonic acid concentrations did not restore 5-LO activity indicated that the NO2-FA-mediated inhibition of 5-LO was noncompetitive.

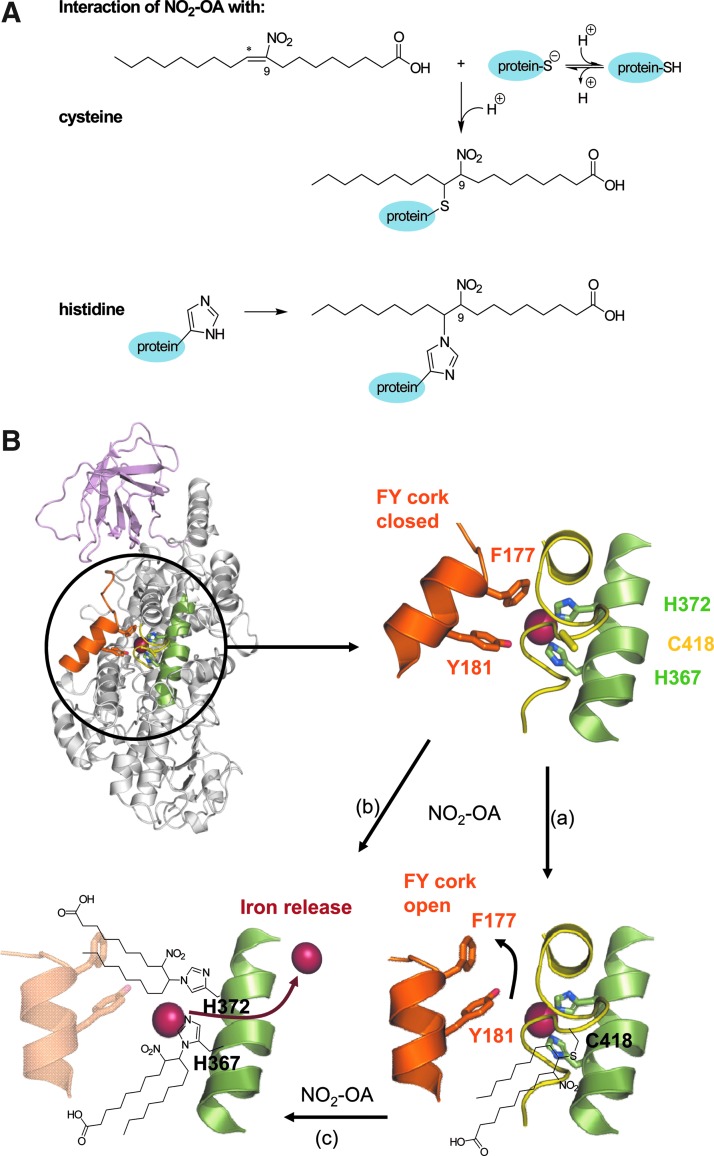

To determine the mechanism of inhibition, human recombinant 5-LO was incubated with NO2-OA or OA, and covalent modification was analyzed by MS. Using this approach, the adduction of five histidine residues (His360, His362, His367, His372, and His432) in the catalytic domain of the 5-LO was detected, two of which (His367 and His372) are critical for maintaining iron coordination (13). Importantly, not all of the iron-coordinating histidine residues in the active site were targeted. While the adduction of critical histidine residues could explain the inhibition of 5-LO activity, it is unlikely that this accounted for the selective inhibition of 5-LO by NO2-FAs, as the catalytic domains of all three LO enzymes are largely conserved (13). Therefore, we focused on four cysteine residues (Cys159, Cys300, Cys416, and Cys418) within 5-LO that are critical for enzymatic activity. Both Cys416 and Cys418 are unique to 5-LO, and they are not conserved in the human, rat, or murine platelet-type 12-LO or 15-LO-1 isoforms (17). We found that the peptide containing Cys416 and Cys418 was alkylated by NO2-OA, and mutation studies indicated that Cys418 was critical for the NO2-FA-mediated inhibition of the 5-LO. Unfortunately, numerous approaches to immunoprecipitate 5-LO from lung lysates and to confirm these data in an in vivo setting failed, because the amount as well as purity of immunoprecipitated 5-LO was inadequate for MS analyses. However, from the resolved structure of 5-LO, it appears that under normal conditions, the catalytic domain of the enzyme is protected against electrophilic fatty acids species (13), as substrate entry depends on a conformational change of amino acids, which, in turn, results in removal of the “FY cork” formed by Tyr181 and Phe177 (13). It was previously speculated that the covalent modification of Cys416 would interfere with the FY cork, preventing the entry of arachidonic acid and, thus, irreversibly inhibiting the 5-LO (17). The present data suggest that the alkylation of Cys418; which is located close to the substrate entry channel, similarly blocks arachidonic acid entry into the catalytic site. The absence of Cys418 along with a shifted substrate entry channel in the case of platelet-type 12-LO and 15-LO-1 would be expected to render the enzymes insensitive to inhibition by alkylation as well as to electrophilic attack and ensure maintained substrate access to the catalytic site. This speculation is supported by the facts that (i) NO2-OA and NO2-LA elicited the release of iron from the wild-type 5-LO but not the C418S mutant enzyme and (ii) the resistance of the C418S mutant 5-LO as well as the platelet-type 12-LO and 15-LO-1 toward NO2-FA.

To determine whether the NO2-FA-induced inhibition of 5-LO was physiologically relevant, lung injury, systemic inflammation, and lipid profiles were assessed in LPS-treated mice. This model was chosen, as several studies have highlighted the role of 5-LO and LTs in the development and maintenance of sepsis (7, 12). In addition, the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to inflamed tissue can be mediated by 5-LO products (29, 41). The in vivo administration of NO2-OA to mice significantly reduced the systemic and pulmonary responses to LPS to an extent comparable to the 5-LO inhibitor zileuton. Moreover, NO2-OA treatment limited the formation of 5-LO products, without affecting 12-HETE formation, in plasma and lung tissue. Indeed, NO2-FA-mediated attenuation of murine sepsis was 5-LO dependent, as the administration of NO2-OA failed to exert any anti-inflammatory effect in LPS-stimulated 5-LO−/− mice.

The anti-inflammatory effects of NO2-FAs have been attributed to the alkylation of target proteins, including NFκB-p65 (8), which, when activated, results in increased LOX expression (5, 28). Indeed, there can be a feed-forward response, as LTs further propagate inflammation (11) and LTB4 enhances NFκB activation (36). NO2-FAs may also target PPAR-γ (33) and Nrf2 (18), which also affect the expression of inflammatory proteins. Given this information, it was necessary to determine whether the anti-inflammatory actions of the NO2-FAs observed in vivo could be attributed to the alkylation of 5-LO or to effects on transcription factors. NO2-OA only modestly decreased the expression of the NFκB-regulated genes TNF-α, MCP-1 and the three LOX genes (especially when compared with the effects of the inhibitor of the IκB kinase). It was also possible to rule out an effect that was mediated via Nrf2, as the pulmonary expression of HO-1 was unaffected by NO2-OA in either solvent or LPS-treated mice. NO2-FAs can also target glutathione peroxidases, which are known to suppress cellular 5-LO activity in neutrophils (16), B cells (37), and monocytes (33) but there was no detectable effect of NO2-OA on cellular GPx activity. Thus, the alkylation of the 5-LO by the NO2-FAs rather than a more general effect on NFκB, Nrf2, or glutathione peroxidases seems to underlie the effects observed.

Electrophilic fatty acids, such as NO2-OA or NO2-LA, readily react with nucleophilic residues such as thiolates or imidizols within proteins (Fig. 7A). Our data indicate that the alkylation of the surface cysteine Cys418 and the iron coordinating histidines (His367, and His372) by NO2-FA adduction results in the inhibition of 5-LO (Fig. 7B). NO2-FA entry to the catalytic core may rely on the alkylation of Cys418, which seems to be important for its stabilization. Therefore, the accumulation of NO2-FAs during the inflammatory response may act as a natural feedback mechanism to attenuate inflammatory cell mobilization and recruitment and, thus, limit cytokine production and promote resolution at sites of injury. It is tempting to speculate that synthetic homologues of the NO2-FAs may represent an innovative strategy to treat inflammatory disease and may represent a novel potential pharmacological strategy for 5-LO inhibition, which might have therapeutic implications for asthma (26, 27).

FIG. 7.

NO2-FA-mediated 5-LO inhibition. (A) Reaction of 9-NO2-OA with a cysteine or histdine residue within target proteins. Electrophilic adduction of NO2-OA to a thiolate of a cysteine (upper scheme) or imidazol residue of histidine (lower scheme) leads to alkylation of the corresponding residue. (B) Ribbon diagram of human 5-LO (PDB code 3o8y (2)) showing the FY-cork (orange), the domain containing the iron coordinating H367 and 372 (green), as well as the domain harboring C418 (yellow); the C2-like domain (light pink) and the catalytic domain (gray). The detailed view of the 5-LO catalytic domain shows the F177 and Y181 residues that form the FY-cork as well as the iron coordinating residues H367 and 372 and C418. The alkylation of C418 (a) along with the alkylation of H367 and H372 leads to the release of iron (red sphere; b) and inhibition of the 5-LO. The adduction of NO2-OA to C418 may enable the entry of NO2-FA to the catalytic domain before the modification of H367 and 372 (c). The ribbon diagrams were prepared using PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Materials and Methods

Materials

Fatty acids and derivatives; arachidonic acid, linoleic acid (ocatadeca-9,12-dienoic acid, LA), oleic acid (ocatadeca-9-enoic acid, OA), nitro-linoleic acid (mixture of 4 regioisomeres: 9-/10-/12-/13-nitro-ocatadeca-9,12-dienoic acid, NO2-LA), and nitro-oleic acid (mixture of 2 regioisomeres: 9-/10-nitro-ocatadeca-9-enoic acid, NO2-OA) as well as recombinant murine platelet-type 12-LO were obtained from Cayman Chemicals. Collagenase type 2 was obtained from Worthington Biochemical Corp. Recombinant human 15-LO-1 was from Biomol. LPS from Salmonella enterica and all other compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Cysteine residues in the 5-LO (Cys159, Cys300, Cys416, Cys418, or all four) were replaced with serine using the QuickChange kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Recombinant 5-LO activity assay

Plasmids (pT3–5-LO) encoding either the wild-type or mutated human 5-LO were transformed into Escherichia coli Bl21 (DE3) cells, the plasmid expressed and the enzyme purified. Briefly, cells were lysed in triethanolamine/HCl (50 mM), pH 8.0, EDTA (5 mM), soybean trypsin inhibitor (60 μg/ml), phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (1 mM), dithiothreitol (1 mM), and lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and sonicated (3×10 s). After a preclearing centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min, the lysate was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 70 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then applied to an ATP-agarose column (Sigma A2767), and affinity chromatography was performed as described (15). Partially purified 5-LO was immediately used for in vitro activity assays. Purified 5-LO (activity 0.6 μmol·min−1·mg−1) was added to 1 ml of reaction buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM ATP) and incubated for 15 min at 4°C with test compounds or DMSO (1‰). After warming the samples to 37°C, product formation was induced by adding CaCl2 (2 mM) and arachidonic acid (20 μM) and stopped after 10 min by adding methanol (1 ml, 4°C).

Recombinant 12- and 15-LO activity assay

Either recombinant murine 12- or human 15-LO (in each case 560 ng) were added to 100 μl of PBS and incubated for 10 min at 37°C with solvent (DMSO) or test compounds. The reaction was started with arachidonic acid (10 μM) and stopped after 20 min by adding acetonitril (600 μl, 4°C). Total amounts of 12- and 15-HETE, respectively, were quantified by LC-MS/MS.

Isolation of human PMNL, WBCs, and platelets

Human PMNL were freshly isolated from leukocyte concentrates as described (39). In brief, leukocyte concentrates were sedimented on a dextran gradient and centrifuged on a Ficoll gradient (LSM 1077; PAA Laboratories) at 800 g for 10 min. Erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis. Human PMNL (7–9 106 cells/ml; purity>95%) were resuspended in a reaction buffer consisting of PBS (pH 7.4) that was supplemented with glucose (1 mg/ml) and CaCl2 (1 mM). The upper phase of the Ficoll gradient (platelet-rich plasma) was further centrifuged (800 g for 7 min) to obtain platelets that were then also suspended in reaction buffer. WBCs were freshly isolated from human leukocyte concentrates. First, PMNL were isolated as described earlier and resuspended in RPMI 1640 (PAA Laboratories) that was supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). In parallel, the mononuclear ring from the Ficoll gradient was further centrifuged (800 g for 10 min) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 that was supplemented with 0.1% BSA to obtain monocytes. PMNL and monocytes were counted and combined in equal parts to obtain 6×106 WBC/ml and were used immediately.

To obtain cell homogenates, human PMNL were sonicated (3×10 s) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells, nuclei, and mitochondria. The supernatant (cell homogenate) was further centrifuged at 100,000 g for 70 min to gain the cytosolic fraction (supernatant). Cell homogenates or the corresponding cytosolic fractions (100,000 g supernatants) were used for the inhibitor studies.

Determination of 5-LO activity in intact human PMNL and cell preparations

Freshly isolated human PMNL were pre-incubated in 1 ml reaction buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, 1 mg/ml glucose, and 1 mM CaCl2) with the test compounds or vehicle (1‰ DMSO) at 37°C for 15 min. Reactions were started by the addition of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (2.5 μM), sodium arsenite (10 μM), or NaCl (300 mM) with or without arachidonic acid as indicated. The 5-LO inhibitor, BWA4C (N-hydroxy-N-[(E)-3-[3-(phenoxy)phenyl]prop-2-enyl]acetamide, BW, 1 μM), was included as a control. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of ice-cold methanol (1 ml). In the case of GM-CSF/fMLP stimulation, cells were primed with GM-CSF (1 nM) for 30 min before the addition of fMLP (100 nM, 5 min). Test compounds or vehicle (1‰ DMSO) were added 10 min before treatment with fMLP. In addition, cell preparations of human PMNL, that is, cell homogenates and cytosolic fractions, were used for the testing of 5-LO inhibitors. Therefore, equal amounts of cellular preparations (producing 1000 ng of 5-LO metabolites within 10 min) were incubated with solvent (1‰ DMSO) or test compounds for 15 min at 4°C. Thereafter, the reaction was started by pre-warming (37°C) as well as by the addition of CaCl2 (2 mM) and arachidonic acid (20 μM) and stopped by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold methanol after 10 min.

Reversibility of 5-LO inhibition in human PMNL

To determine the reversibility of the test compounds, a “wash out” assay was performed. Briefly, freshly isolated human PMNL were incubated with LA, OA, NO2-LA, NO2-OA (all 10 μM), or control substances for 15 min and then washed thrice with reaction buffer. Next, A23187 (2.5 μM) and arachidonic acid (2 μM) were added; the reversible 5-LO inhibitor BWA4C (1 μM) and the irreversible 5-LO inhibitor U73122 (10 μM) were used as controls.

Determination of 12-LO activity in intact human platelets

After pre-incubation of 108 human platelets in reaction buffer with test compound or vehicle (1‰ DMSO) for 15 min at room temperature, product formation was stimulated by the addition of arachidonic acid (5 μM). After 10 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped with 1 ml methanol.

Determination of 15-LO activities in intact human eosinophils

PMNL preparations from human buffy coats exhibit a purity of 95%, and mainly eosinophils expressing Ca2+-dependent 15-LO-1 account for the remaining 5% of cells. Thus, formation of the 15-LO-1 product 15-HETE was quantified from human PMNLs that were stimulated with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (2.5 μM) in 1 ml reaction buffer on preincubation with the test compounds or vehicle (1‰ DMSO) at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped after 10 min by the addition of 1 ml methanol.

High-performance liquid chromatography-based fatty acid quantification

After the addition of 1 ml methanol, fatty acids were extracted by solid-phase extraction and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described (40). LTB4, its all-trans isomers, and 5-HETE were combined to give a global indication of 5-LO product formation. Both 15-HETE from PMNL preparations and 12-HETE levels in platelets were detected by HPLC. Values were normalized to solvent control (% sol).

Mass spectrometry

Human recombinant 5-LO was incubated with solvent (1‰ DMSO), OA, and NO2-OA (each 5 μM) in reaction buffer for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA; final concentration 10%). Samples were incubated for 30 min on ice, centrifuged (16,000 g, 4°C, 30 min), washed with ice-cold 80% acetone, and dried. The TCA-precipitated proteins were dissolved in ammonium hydrogen carbonate (50 mM) buffer, reduced with dithiothreitol (5 mM), and alkylated with iodoacetamide (15 mM). After digestion overnight with MS grade trypsin (Promega), samples were dried and resuspended in 5% acetonitrile that was acidified with 0.5% formic acid. An MS analysis of tryptic peptides was performed as previously described (16). Mass spectra were analyzed in a Proteome Discoverer 1.3 environment (Thermo Scientific) using Mascot 2.2 as the search engine with the following search parameters: maximum of one missed cleavage, cysteine carbamidomethylation, methionine oxidation, and alkylation of histidine and cysteine by NO2-OA (mass shift+327.240959 Da) as optional modifications. The mass tolerance was set to 12 ppm and 0.8 Da for MS and MS/MS scans, respectively. Spectra were matched against the reviewed human protein database downloaded from www.uniprot.org. The calculated false discovery rate of the peptide hits was lower than 5%. Label-free quantification was done by integration of precursor peak areas using the Precursor Ion Area Detector node of Proteome Discoverer software.

Sepsis model

All animal investigations were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidlelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals, and all animal experiments were approved by the Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt (license # F28/24). Eight-week-old male C57BL/6/J (wild-type, WT) or 5-LO-deficient (5-LO−/−) mice (Charles River Laboratories) received a total of three doses of vehicle (50% DMSO), NO2-OA, or OA (20 μmol/kg, i.p.), 1 and 4 h before, as well as 4 h after, LPS (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or solvent (PBS, 100 μl, i. p.) administration. One group of wild-type animals received the 5-LO inhibitor zileuton (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h before LPS injection. Sixteen hours after LPS administration, the animals were sacrificed, and lung and blood samples were taken for subsequent analysis. Whole blood cell profiles were measured using an automated cell counter (VetScan HM5; Abaxis) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Flow cytometry

One lobe of murine lung was digested to quantify infiltrated monocytes and neutrophils. Briefly, samples were cut into small pieces and digested in a mixture of collagenase 2 and dispase 2 (37°C, 60 min), filtered through a 70 μm filter, recovered by centrifugation (800 g, 10 min, 10°C), and washed with PBS. Erythrocytes were removed using an erythrocyte lysis buffer. Cells (3×106) were labeled with antibodies that were directed against CD11b (eBioscience), CD45, CD11c, and Gr-1 (all from Becton and Dickinson) and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton and Dickinson) and CellQuest software. Neutrophils were defined as being CD45+, CD11b+, and Gr-1+, and monocytes were defined as being CD45+, CD11b+, and Gr-1−.

Eicosanoid profile

The leukotriene and PG profiles of murine plasma and lung samples were performed after liquid–liquid extraction of 100 μl plasma and 20 mg fresh lung tissue with acetonitril. Lung tissues were homogenized before extraction using a tissue lyser (Quiagen).

The metabolites were analyzed using a C18 reversed-phase chromatographic column (Gemini NX C18; Phenomenex) that was coupled to a tandem MS system (QTrap 5500; AB Sciex). Quantification was performed using internal standards (with deuterated standards) and one precursor to product ion transition per analyte: m/z 351→315 for PGD2, m/z 351→271 for PGE2, m/z 353→309 for PGF2α, and m/z 369→169 for 6-keto-PGF1α and thromboxane B2 (TXB2). For 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE and LTB4, the measured mass transitions were as follows: m/z 319→115, m/z 319→179, m/z 319→219, and m/z 335→195, respectively. In all cases, a calibration curve from 0.5 to 2500 ng/ml was constructed.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Human WBCs were treated with OA, NO2-OA, LA, NO2-LA (each 5 μM), or 4-(2′-aminoethyl)amino-1,8-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]quinoxaline (BMS-345541, BMS; 8 μM; Calbiochem); an inhibitor of the IκB kinase, for 8 h, in the presence and absence of LPS (100 ng/ml). The cells were centrifuged and directly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using TriReagent, and equal amounts were used for reverse transcription with Superscript III (Invitrogen) using random hexamer primers. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a CYBER green master mix (Abgene) with appropriate primers for human or murine 5-LO (ALOX5), ALOX12, ALOX15, MCP-1 and TNF-α, IL1β), IL6, iNOS, MMP9, HO-1, VCAM1, ICAM1, GPx1, and GPx4. Data were normalized to 18S mRNA expression using the ΔΔCT method.

Iron determination

Wild-type and C418S mutant (replacement of Cys418 to serine) 5-LO were purified by anion exchange chromatography as previously described (3, 14) and used for the quantification of the iron content. Equal amounts (30 ng/reaction) of enzymes were incubated with solvent (1‰ DMSO), 5 μM of OA, LA, NO2-OA, or NO2-LA for 15 min, dialyzed overnight (Slide-A-Lyzer G2 dialysis cassette; Thermo Scientific) before HNO3 (0.015 M final concentration) was added to each sample. Iron release was determined by graphite furnace AAS using a Perklin Elmer Zeeman AAS 4110 ZL spectrometer as described (42). 20 μl of each sample were injected into the AAS, dried in two steps (100°C and 200°C), charred at 1300°C, and atomized at 2300°C. The iron content was calculated from the absorption at 248.3 nm using an external standard curve (ranging from 5 to 100 ng/ml) that was freshly diluted from a stock standard solution in 0.015 M HNO3.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) values were obtained from measurements of five different concentrations of the compounds in three to six independent experiments and were determined by graphical analysis (linear interpolation between the points at 50% activity) using GraphPadPrism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data were subjected to one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferonni's post tests for multiple comparisons. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- AAS

atomic absorption spectrophotometry

- ALOX

arachidonate-lipoxygenase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- fMLP

N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GPx

glutathione peroxidise

- H(P)ETE

hydro(peroxy-)eicosatetraenoic acid

- HETE

hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IκB

inhibitor of NFκB

- LA

linoleic acid

- LO

lipoxygenase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LT

leukotrienes

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MMP

matrix metalloprotease

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NFκB

nuclear factor κB

- NO

nitric oxide

- NO2-FA

nitro-fatty acids

- NO2-LA

nitro-linoleic acid

- NO2-OA

nitro-oleic acid

- OA

oleic acid

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PG

prostaglandins

- PMNL

polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- WBC

white blood cell

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Marie von Reutern, Isabella Schlöffel, and Sven George for their excellent technical support. This study was supported by the LOEWE Lipid Signaling Forschungszentrum Frankfurt (LiFF) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Exzellenzcluster 147 “Cardio-Pulmonary Systems” and SFB 815/Z1). T.J.M. is the recipient of a Heisenberg fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Author Disclosure Statement

Bruce A. Freeman acknowledges financial interest in Complexa, Inc. No competing financial interests exist for the other authors.

References

- 1.Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, and Freeman BA. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem 280: 42464–42475, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, and Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 235–242, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brungs M, Radmark O, Samuelsson B, and Steinhilber D. Sequential induction of 5-lipoxygenase gene expression and activity in Mono Mac 6 cells by transforming growth factor beta and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 107–111, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceaser EK, Moellering DR, Shiva S, Ramachandran A, Landar A, Venkartraman A, Crawford J, Patel R, Dickinson DA, Ulasova E, Ji S, and Darley-Usmar VM. Mechanisms of signal transduction mediated by oxidized lipids: the role of the electrophile-responsive proteome. Biochem Soc Trans 32: 151–155, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra A, Ferreira-Alves DL, Sirois P, and Thirion JP. Cloning of the guinea pig 5-lipoxygenase gene and nucleotide sequence of its promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 185: 489–495, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole MP, Rudolph TK, Khoo NK, Motanya UN, Golin-Bisello F, Wertz JW, Schopfer FJ, Rudolph V, Woodcock SR, Bolisetty S, Ali MS, Zhang J, Chen YE, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, and Bauer PM. Nitro-fatty acid inhibition of neointima formation after endoluminal vessel injury. Circ Res 105: 965–972, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collin M, Rossi A, Cuzzocrea S, Patel NS, Di PR, Hadley J, Collino M, Sautebin L, and Thiemermann C. Reduction of the multiple organ injury and dysfunction caused by endotoxemia in 5-lipoxygenase knockout mice and by the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton. J Leukoc Biol 76: 961–970, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR, Batthyany C, Chacko BK, Feng X, Patel RP, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, and Chen YE. Nitrated fatty acids: endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem 281: 35686–35698, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan RW. and Gale PH. Inhibition of mammalian 5-lipoxygenase by aromatic disulfides. J Biol Chem 260: 11554–11559, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 294: 1871–1875, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk CD. Leukotriene modifiers as potential therapeutics for cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4: 664–672, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funk CD. Leukotriene inflammatory mediators meet their match. Sci Transl Med 3: 66ps3, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert NC, Bartlett SG, Waight MT, Neau DB, Boeglin WE, Brash AR, and Newcomer ME. The structure of human 5-lipoxygenase. Science 331: 217–219, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafner AK, Cernescu M, Hofmann B, Ermisch M, Hornig M, Metzner J, Schneider G, Brutschy B, and Steinhilber D. Dimerization of human 5-lipoxygenase. Biol Chem 392: 1097–1111, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammarberg T, Provost P, Persson B, and Radmark O. The N-terminal domain of 5-lipoxygenase binds calcium and mediates calcium stimulation of enzyme activity. J Biol Chem 275: 38787–38793, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heide H, Bleier L, Steger M, Ackermann J, Drose S, Schwamb B, Zornig M, Reichert AS, Koch I, Wittig I, and Brandt U. Complexome profiling identifies TMEM126B as a component of the mitochondrial complex I assembly complex. Cell Metab 16: 538–549, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornig M, Markoutsa S, Hafner AK, George S, Wisniewska JM, Rodl CB, Hofmann B, Maier T, Karas M, Werz O, and Steinhilber D. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase by U73122 is due to covalent binding to cysteine 416. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821: 279–286, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kansanen E, Bonacci G, Schopfer FJ, Kuosmanen SM, Tong KI, Leinonen H, Woodcock SR, Yamamoto M, Carlberg C, Yla-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, and Levonen AL. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids activate NRF2 by a KEAP1 cysteine 151-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem 286: 14019–14027, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Volger OL, Leinonen H, Kivela AM, Hakkinen SK, Woodcock SR, Schopfer FJ, Horrevoets AJ, Yla-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, and Levonen AL. Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J Biol Chem 284: 33233–33241, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley EE, Batthyany CI, Hundley NJ, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Del Rio JM, Schopfer FJ, Lancaster JR, Jr., Freeman BA, and Tarpey MM. Nitro-oleic acid, a novel and irreversible inhibitor of xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem 283: 36176–36184, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khoo NK. and Freeman BA. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids: anti-inflammatory mediators in the vascular compartment. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10: 179–184, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koenitzer JR. and Freeman BA. Redox signaling in inflammation: interactions of endogenous electrophiles and mitochondria in cardiovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1203: 45–52, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Zhang J, Schopfer FJ, Martynowski D, Garcia-Barrio MT, Kovach A, Suino-Powell K, Baker PR, Freeman BA, Chen YE, and Xu HE. Molecular recognition of nitrated fatty acids by PPARγ. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 865–867, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montuschi P. Leukotrienes, antileukotrienes and asthma. Mini Rev Med Chem 8: 647–656, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montuschi P. and Peters-Golden ML. Leukotriene modifiers for asthma treatment. Clin Exp Allergy 40: 1732–1741, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montuschi P. LC/MS/MS analysis of leukotriene B4 and other eicosanoids in exhaled breath condensate for assessing lung inflammation. J Chromatogr B 877: 1272–1280, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montuschi P. and Barnes PJ. New perspectives in pharmacological treatment of mild persistent asthma. Drug Discov Today 16: 1084–1091, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene 18: 6853–6866, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavanelli WR, Gutierrez FR, Mariano FS, Prado CM, Ferreira BR, Teixeira MM, Canetti C, Rossi MA, Cunha FQ, and Silva JS. 5-Lipoxygenase is a key determinant of acute myocardial inflammation and mortality during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Microbes Infect 12: 587–597, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, and Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: regulation of expression and enzyme activity. Trends Biochem Sci 32: 332–341, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi A, Pergola C, Koeberle A, Hoffmann M, Dehm F, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S, Werz O, and Sautebin L. The 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, zileuton, suppresses prostaglandin biosynthesis by inhibition of arachidonic acid release in macrophages. Br J Pharmacol 161: 555–570, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudolph V, Schopfer FJ, Khoo NK, Rudolph TK, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Groeger AL, Golin-Bisello F, Chen CS, Baker PR, and Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, β-oxidation, and protein adduction. J Biol Chem 284: 1461–1473, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schopfer FJ, Cole MP, Groeger AL, Chen CS, Khoo NK, Woodcock SR, Golin-Bisello F, Motanya UN, Li Y, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Bonacci G, Baker PR, Xu HE, Batthyany CI, Chen YE, Hallis TM, and Freeman BA. Covalent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ adduction by nitro-fatty acids: selective ligand activity and anti-diabetic signaling actions. J Biol Chem 285: 12321–12333, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PR, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, Chen K, Chen YE, and Freeman BA. Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 2340–2345, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, and Freeman BA. Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev 111: 5997–6021, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serezani CH, Lewis C, Jancar S, and Peters-Golden M. Leukotriene B4 amplifies NF-κB activation in mouse macrophages by reducing SOCS1 inhibition of MyD88 expression. J Clin Invest 121: 671–682, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitturi DA, Chen CS, Woodcock SR, Salvatore SR, Bonacci G, Koenitzer JR, Stewart NA, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ. Modulation of nitro-fatty acid signaling: prostaglandin reductase-1 is a nitroalkelene reductase. J Biol Chem 288: 25626–25637, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Liu H, Jia Z, Olsen C, Litwin S, Guan G, and Yang T. Nitro-oleic acid protects against endotoxin-induced endotoxemia and multiorgan injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F754–F762, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werz O, Burkert E, Samuelsson B, Radmark O, and Steinhilber D. Activation of 5-lipoxygenase by cell stress is calcium independent in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood 99: 1044–1052, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werz O. and Steinhilber D. Selenium-dependent peroxidases suppress 5-lipoxygenase activity in B-lymphocytes and immature myeloid cells. The presence of peroxidase-insensitive 5-lipoxygenase activity in differentiated myeloid cells. Eur J Biochem 242: 90–97, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werz O. and Steinhilber D. Therapeutic options for 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther 112: 701–718, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang YY, Lind B, Radmark O, and Samuelsson B. Iron content of human 5-lipoxygenase, effects of mutations regarding conserved histidine residues. J Biol Chem 268: 2535–2541, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.