Abstract

We have isolated three novel strains of Trichoderma (two T. harzianum and one T. atroviride) from wild mushroom and tree bark, and evaluated their biocontrol potential against Sclerotium delphinii infecting cultivated cotton seedlings. T. harzianum strain CICR-G, isolated as a natural mycoparasite on a tree-pathogenic Ganoderma sp. exhibited the highest disease suppression ability. This isolate was formulated into a talcum-based product and evaluated against the pathogen in non-sterile soil. This isolate conidiated profusely under conditions that are non-conducive for conidiation by three other Trichoderma species tested, thus having an added advantage from commercial perspective.

Keywords: Trichoderma, Biological control, Formulation, Sclerotium delphinii, Cotton

Introduction

Trichoderma spp. are widely used as commercial biofungicides all over the world (Harman 2006; Harman et al. 2004; Howell 2006; Lorito et al. 2010; Schuster and Schmoll 2010; Shoresh et al. 2010; Verma et al. 2007). In India alone, more than 250 commercial formulations are available (Singh et al. 2012), but almost all of them are based on a single strain of T. viride (recently reclassified as T. asperelloides; Mukherjee et al. 2013b), isolated from rhizosphere (Sankar and Jeyarajan 1996). Soil/rhizosphere has been classically viewed as the main habitat of Trichoderma, even though the maximum diversity of this species occurs aboveground e.g., on tree bark and wild mushrooms, and mycotrophy is viewed as the ancestral trait of this genus (Druzhinina et al. 2011). Consequently, only a few strains have been isolated from soil/rhizosphere and used as commercial biopesticides, and the above ground source remained largely unexploited in agriculture, except, perhaps, for a few endophytic strains, such as T. gamsii (http://www.clemson.edu/extension/horticulture/fruit_vegetable/peach/diseases/arr_biological.html). In the present study, we have isolated three novel Trichoderma strains from wild mushroom and tree bark and evaluated their potential as biocontrol agents. We have also developed a formulation product based on the most effective strain and evaluated this formulation as seed treatment for suppression of seed and root rot of cotton caused by Sclerotium delphinii, an emerging pathogen of cultivated cotton (Mukherjee et al. 2013a).

Results and discussion

Continued commercial success of Trichoderma would depend on identification of novel strains adapted to local conditions. Since the diversity of Trichoderma is profound on the above-ground, the success of novel strains to be developed as biocontrol products would be greater if the newer isolates are obtained that are naturally mycoparasites, as against collecting a large number of typical saprophytes (from soil) and mass screening. The current study has focused on isolation of Trichoderma from wild mushroom and tree bark and evaluation for biocontrol against a newly reported pathogen (S. delphinii, MTCC 11568) of cotton.

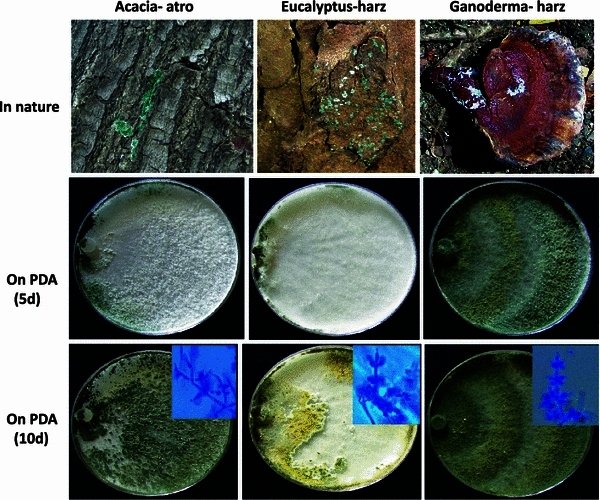

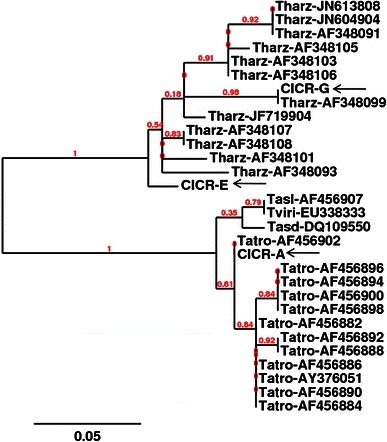

Of the three new isolates, T. harzianum CICR-G (MTCC 11511) was isolated from a parasitized basidiocarp of a Ganoderma sp. that was growing as a parasite on roots of an Acacia tree, T. harzianum CICR-E (MTCC 11500) was isolated from the bark of an Eucalyptus tree and T. atroviride CICR-A (MTCC 11512) was isolated from the bark of an Acacia tree (Fig. 1). There was large cultural variability among the two T. harzianum isolates which were also phylogenetically distantly related (Fig. 2). The Tef1 large (fourth) intron sequence data from all the three isolates have been deposited with GenBank viz. accession nos. KC679853 (T. harzianum CICR-G), KC679855 (T. harzianum CICR-E) and KC679854 (T.atroviride CICR-A).

Fig. 1.

Natural occurrence and cultural characteristics of three isolates of Trichoderma. Top left: occurrence of T. atroviride CICR-A on Acacia sp. bark; Top middle: occurrence of T. harzianum CICR-E on Eucalyptus sp. bark; Top right: occurrence of T. harzianum CICR-G on a basidiocarp of Ganoderma sp. Middle panel: cultural characteristics on PDA, photographed after 5 days of inoculation. Lower panel: cultural characteristics on PDA, photographed after 10 days of inoculation. Inset: conidiophore structures observed under microscope

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Trichoderma isolates based on the sequence of the fourth intron of translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene. The positions of new isolates are indicated with arrows

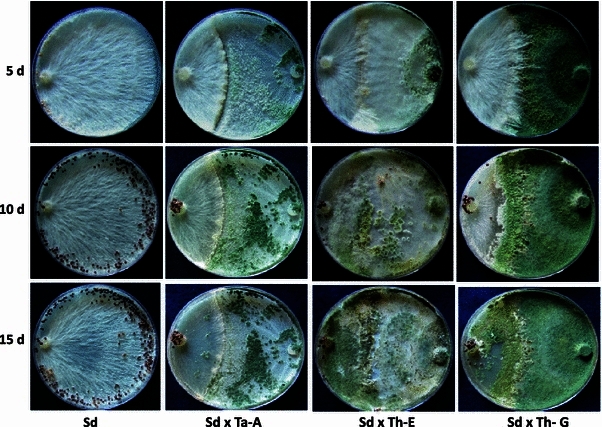

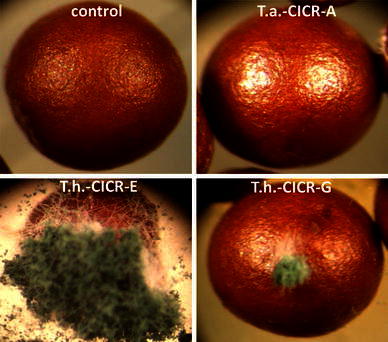

In confrontation assay, both T. harzianum CICR-G and T. harzianum CICR-E were able to overgrow the test pathogen, but T. atroviride CICR-A failed to overgrow S. delphinii colony even after prolonged incubation (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the ability to colonize the sclerotia (resting structures of S. delphinii) also differed- T. harzianum CICR-E being the most effective while T. atroviride CICR-A being unable to colonize the sclerotia (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Confrontation assay for antagonism of Trichoderma isolates on Sclerotium delphinii

Fig. 4.

Colonization of sclerotia of Sclerotium delphinii by Trichoderma isolates, observed under a stereo binocular microscope. Control: a sclerotium from a pure culture

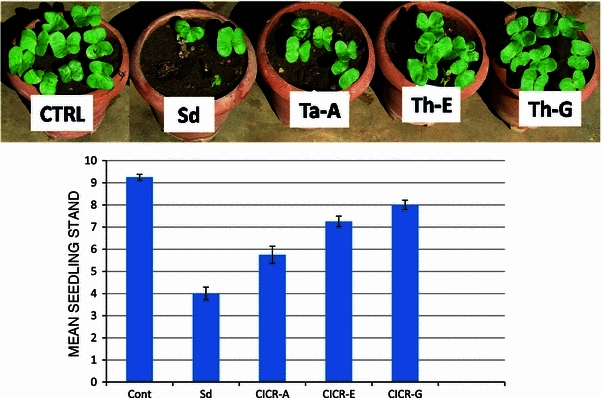

The isolates also differed in their ability to suppress S. delphinii in sterile soil. T. harzianum CICR-G being the most effective, while T. atroviride CICR-A being the least effective (Fig. 5). Based on this experiment, T. harzianum CICR-G was selected for further studies. It may be noted that even though T. harzianum CICE-E was more effective in confrontation assay, T. harzianum CICR-G was better as a biocontrol agent in pot soil. This is quite common, as the behaviour of an antagonist in pure culture is many a times different from that in soil where the performance of the bioagent is an outcome of interactions of the antagonist with the pathogen under the influence of several biotic and abiotic factors.

Fig. 5.

Biological suppression of Sclerotium delphinii by Trichoderma isolates in cotton. Data are mean of 4 replicates ± SE

For developing a formulation product, we assessed the ability of T. harzianum CICR-G to conidiate in PDB of varying strengths. Interestingly, this isolate conidiated profusely within 3 days on PDB of one-fourth strength (Fig. 6). After 7 days, the number of conidia produced was 4.5 × 1010, 7 × 1010 and 4.7 × 1010, on 0.25×, 0.5× and 1× PDB, respectively (in a flask with 100 ml medium). We mixed the mat from two flasks (0.5× PDB) per kg talcum powder and after drying and packaging, obtained an initial approximate CFU (colony forming units) count of 108/g formulation product, designated as TrichoCASH 1 % WP.

Fig. 6.

Conidiation of Trichoderma harzianum CICR-G on different strengths of PDB after 3 days of incubation. 1×: full strength, 0.5×: half strength, 0.25×: a quarter strength

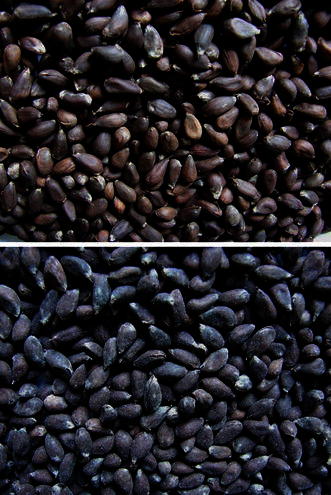

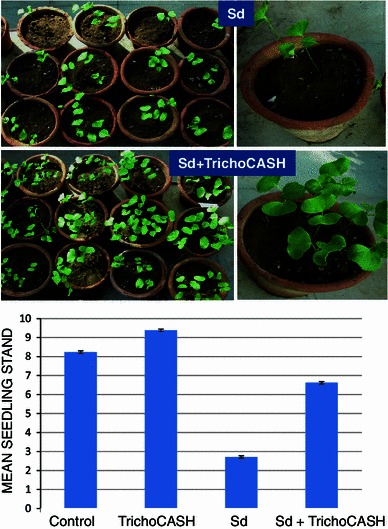

Wet seed treatment (5 g/kg seeds) provided a uniform coating on acid de-linted cotton seeds (Fig. 7) that were used for sowing in non-sterile soil pre-infested with S. delphinii. Treating the seeds with TrichoCASH significantly protected seeds and seedlings from S. delphinii infection in non-sterile soil (Fig. 8). The seedling stand in non-sterile soil not pre-infested with S. delphinii was also significantly higher when seeds were treated with this formulation, as compared to non-treated seeds.

Fig. 7.

Seed treatment with TrichoCASH 1 % WP. Top: untreated cotton seeds; bottom: treated seeds

Fig. 8.

Biological suppression of Sclerotium delphinii in cotton in non-sterile soil. Data are mean of 21 replicates ± SE

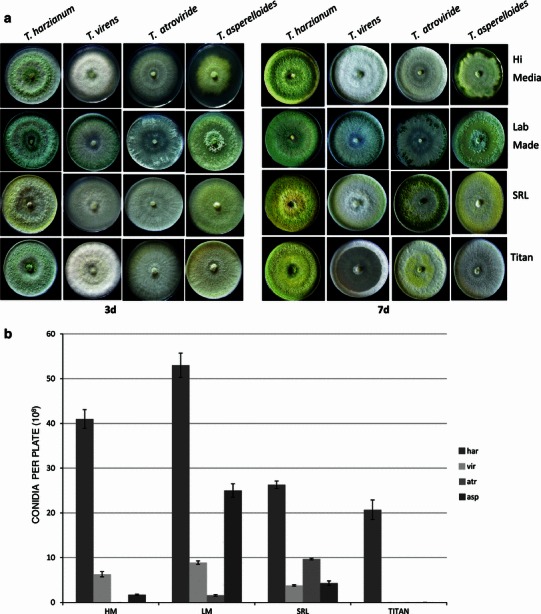

Ability to sporulate under adverse conditions is a desirable trait for biocontrol fungi as this is related to ease of formulation. Of the four different species/strains of Trichoderma tested on four different sources of PDA (lab. made, HiMedia, SRL and Titan media), T. harzianum CICR-G was least affected by the source of the culture medium (Fig. 9a, b). The laboratory made PDA supported conidiation of all the four species tested, but even on this medium there was wide variation in ability to conidiate; T.harzianum CICR-G being the most abundantly sporulating. It is very interesting to note that PDA from different sources have significant effect on conidiation ability of Trichoderma spp., and PDA from some commercial sources did not support conidiation of Trichoderma (except of T. harzianum CICR-G). It needs to be ascertained if the “loss-of-conidiation” of some Trichoderma species often observed in laboratories is related to switch to a different source/batch of PDA procured from commercial sources.

Fig. 9.

a Growth and b conidiation of four Trichoderma species on PDA from various sources. Data are mean of 3 replicates ± SE

S. delphinii, like its close relative S. rolfsii, is a soil-borne pathogen that over winters through the production of highly melanised sclerotial bodies (Punja 1985; Xu et al. 2008). These attributes make it difficult to control using conventional practices. This pathogen, mostly associated with ornamental crops and certain field crops like groundnut, was hitherto not known to occur in cotton (Edmunds et al. 2003; Farr et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2010). We have recently reported this pathogen to be infecting both seedlings and mature cotton plants in field (Mukherjee et al. 2013a). The soil-borne nature of this pathogen would mean that the pathogen might multiply in soil on crop residues and thus, the incidence would increase with time. In the present study, we have isolated a novel T. harzianum strain (naturally occurring as a mycoparasite) that is effective against this emerging pathogen, and also developed a formulation for field applications. The formulation is being tested in multiple locations across India for biocontrol efficacy against seed rot and seedling diseases in cotton.

Experimental procedure

Fungal strains and growth conditions

All the three Trichoderma strains studied here were isolated from Nagpur, Maharashtra, India, either from infected tree-pathogenic Ganoderma sp. or from bark of Eucalyptus sp. and Acacia sp. The fungi were collected with a sterile cotton swab and the conidia suspended in sterile distilled water. The suspension was plated on potato dextrose agar plates after serial dilution and the isolated colonies were further purified by serial dilution and plating (three times). The pathogen Sclerotium delphinii (MTCC 11568) was obtained from our previous studies (Mukherjee et al. 2013a). Routinely, the fungi were grown at ambient temperatures (25–30 °C) on potato dextrose medium prepared in laboratory (200 g potatoes, 20 g dextrose, and 20 g agar–agar, when required, per litre), unless otherwise stated.

Identification of fungi

The fungal strains were identified based on the sequences of the large sub-unit of translation elongation factor 1-alpha (Tef1) as per standard methods (http://www.isth.info/tools/blast/markers.php). In brief, the large (4th) intron of tef1 gene was amplified using the primer pair EF1-728F and EF1-986R as recommended, and the product sequenced using an automated DNA sequencer. The species were identified by BLASTN on the NCBI site and the identity confirmed by comparing the sequences with authentic sequences from the GenBank, and a phylogenetic tree constructed on http://www.phylogeny.fr.

Confrontation assays

Ability of the Trichoderma isolates to antagonize the test pathogen S. delphinii was assessed using confrontation assay on PDA plates by simultaneous inoculation of both Trichoderma and the pathogen near the edge of the plate, placed opposite each other. Ability of Trichoderma to overgrow the pathogen colony and also to colonize the sclerotia was recorded.

Comparative evaluation for biocontrol in green house

S. delphinii was grown on autoclaved sorghum grains for 7 days and was inoculated to sterile soil at 2 g per pot containing 2 kg autoclaved black cotton soil. The pots were covered with poly bags for 2 days to facilitate the establishment of the pathogen and after 2 days, 10 seeds of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, variety PKV 081) treated with Trichoderma spore suspension (107/ml in 0.5 % aqueous carboxy-methyl cellulose) were sown in each pot. Non-treated seeds sown in pathogen-infested soil served as control. Observation on healthy plant stand was recorded after 10 days.

Development of a talc-based formulation product

Based on the performance in green house, the best isolate (T. harzianum CICR-G) was selected for formulation development and subsequent evaluation. A mycelia disc (6 mm diameter) was inoculated in 100 ml PDB at three concentrations of the medium (1×, 0.5× and 0.25×). Conidiation was counted after 7 days and the mycelial mat along with conidia from 0.5× PDB were mixed thoroughly with autoclaved talcum powder pre-treated with 0.5 % CMC (5 g CMC dissolved in 100 ml water mixed with 1 kg talcum powder). The mix was air-dried in a laminar flow hood and the colony forming units were counted on PDA amended with 100 mg/L rose Bengal, after serial dilution. The formulation was named as TrichoCASH 1 % WP.

Evaluation of TrichoCASH in green house

Five g of TrichoCASH was taken in a poly bag, and 25 ml water was added to make a slurry. Cotton seeds were treated with this slurry (@5 g/kg seeds) and seeds dried in shade before sowing (10 seeds per pot) in non-autoclaved pot soil (5 kg capacity pots) pre-infested with S. delphinii as described above. Observations on healthy seedlings were taken after 15 days.

Effect of source of medium on conidiation

We have earlier observed that certain strains of Trichoderma did not conidiate in PDA from various commercial sources, thus posing a limitation in commercial formulations (Mukherjee PK, unpublished). Hence, we evaluated ability of this strain to conidiate on PDA from different commercial sources, vis-à-vis some other commonly used Trichoderma species (T. atroviride- this study, T. asperelloides, T. virens- both kindly gifted by Dr. Ashis Das, NRCC, Nagpur). Mycelial discs were inoculated in the centre of culture plates containing PDA from different commercial sources (Table 1) and observations on conidia production was recorded after 7 days incubation at ambient temperatures. Spores were counted using a hemocytometer, after appropriate dilution.

Table 1.

Media/components used in this study

| Media/component | Manufacturer | Cat. no. | Batch no. | Date of Mfg | Expiry date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDA (infusion from 200 g boiled potatoes), 20 g dextrose (Hi Media), 20 g agar–agar (Hi Media) in 1 litre RO water pH 6.5 | In-house | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PDA 39 g/L RO water pH 6.5 | Hi Media Laboratories, Mumbai | MU096 | 0000138972 | March 2012 | March 2015 |

| PDA 39 g/L RO water pH 6.5 | SRL Laboratories, Mumbai | PM015 | 10062523 | June 2012 | March 2015 |

| PDA 39 g/L RO water pH 6.5 | Titan Biotech, Bhiwandi, Rajasthan | TMV344 | V3411112 | Not mentioned | November 2014 |

| Dextrose | Hi Media Laboratories, Mumbai | RM077 | 0000044659 | March 2009 | Not mentioned |

| Agar–Agar type I | Hi Media Laboratories, Mumbai | RM666 | 0000053188 | February 2009 | February 2014 |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. K. R. Kranthi, Director, Central Institute for Cotton Research, Nagpur, for his encouragement and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Druzhinina IS, Seidl-Seiboth V, Herrera-Estrella A, Horwitz BA, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Mukherjee PK, Zeilinger S, Grigoriev IV, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds BA, Gleason ML, Wegulo SN. Resistance of hosta cultivars to petiole rot caused by Sclerotium rolfsii var. delphinii. Hort Technol. 2003;13:302–305. [Google Scholar]

- Farr DF, Rossman AY, Palm ME, McCray, EB (2006) Fungal Databases. Systematic Botany & Mycology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/

- Harman GE. Overview of mechanisms and uses of Trichoderma spp. Phytopathology. 2006;96:190–194. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species: opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell CR. Understanding the mechanisms employed by Trichodermavirens to effect biological control of cotton diseases. Phytopathology. 2006;96:178–180. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorito M, Woo SL, Harman GE, Monte E. Translational research on Trichoderma: from omics to the field. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:395–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee AK, Mukherjee PK, Kranthi S (2013a) Sclerotium delphinii infecting cultivated cotton in India- a first record. New Disease Reports (Submitted)

- Mukherjee PK, Mukherjee AK, Kranthi S (2013b) Reclassification of Trichoderma viride (TNAU), the most widely used commercial biofungicide in India, as Trichoderma asperelloides. Open Biotechnol J 7:7–9. doi:10.2174/1874070701307010007

- Punja ZK. The biology, ecology, and control of Sclerotium rolfsii. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1985;23:97–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.23.090185.000525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar P, Jeyarajan R. Seed treatment formulation of Trichoderma and Gliocladium for biological control of Macrophomina phaseolina in sesamum. Indian Phytopath. 1996;49:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster A, Schmoll M. Biology and biotechnology of Trichoderma. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;87:787–799. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2632-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M, Harman GE, Mastouri F. Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:21–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh HB, Singh BN, Singh SP and Sarma BK (2012) Exploring different avenues of Trichoderma as a potent bio-fungicidal and plant growth promoting candidate- an overview. Rev Plant Pathol 5:315–426, Scientific Publishers (India), Jodhpur

- Verma M, Brar S, Tyagi R, Surampalli R, Valero J. Antagonistic fungi, Trichoderma spp.: panoply of biological control. Biochem Eng J. 2007;37:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2007.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Gleason ML, Mueller DS, Esker PD, Bradley CA, Buck JW, Benson DM, Dixon PM, Monteiro JEBA. Overwintering of Sclerotium rolfsii and S. rolfsii var. delphinii in different latitudes of the United States. Plant Dis. 2008;92:719–724. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-5-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Harrington TC, Gleason ML, Batzer JC. Phylogenetic placement of plant pathogenic Sclerotium species among teleomorph genera. Mycologia. 2010;102:337–346. doi: 10.3852/08-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]