ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Although many specialists serve as primary care physicians (PCPs), the type of patients they serve, the range of services they provide, and the quality of care they deliver is uncertain.

OBJECTIVE

To describe trends in patient, physician, and visit characteristics, and compare visit-based quality for visits to generalists and specialists self-identified as PCPs.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study and time trend analysis.

DATA

Nationally representative sample of visits to office-based physicians from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1997–2010.

MAIN MEASURES

Proportions of primary care visits to generalist and specialists, patient characteristics, principal diagnoses, and quality.

KEY RESULTS

Among 84,041 visits to self-identified PCPs representing an estimated 4.0 billion visits, 91.5 % were to generalists, 5.9 % were to medical specialists and 2.6 % were to obstetrician/gynecologists. The proportion of PCP visits to generalists increased from 88.4 % in 1997 to 92.4 % in 2010, but decreased for medical specialists from 8.0 % to 4.8 %, p = 0.04). The proportion of medical specialist visits in which the physician self-identified as the patient’s PCP decreased from 30.6 % in 1997 to 9.8 % in 2010 (p < 0.01). Medical specialist PCPs take care of older patients (mean age 61 years), and dedicate most of their visits to chronic disease management (51.0 %), while generalist PCPs see younger patients (mean age 55.4 years) most commonly for new problems (40.5 %). Obstetrician/gynecologists self-identified as PCPs see younger patients (mean age 38.3 p < 0.01), primarily for preventive care (54.0 %, p < 0.01). Quality of care for cardiovascular disease was better in visits to cardiologists than in visits to generalists, but was similar or better in visits to generalists compared to visits to other medical specialists.

CONCLUSIONS

Medical specialists are less frequently serving as PCPs for their patients over time. Generalist, medical specialist, and obstetrician/gynecologist PCPs serve different primary care roles for different populations. Delivery redesign efforts must account for the evolving role of generalist and specialist PCPs in the delivery of primary care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2808-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: primary health care, primary care physicians, specialization, health manpower, patient-centered care

Primary care is defined as providing first contact care that is comprehensive, long-term, person-focused and coordinated.1 In the United States, physicians trained in general internal medicine or family practice typically serve as adult primary care physicians (PCPs), whereas specialists are consulted for advice regarding diagnosis or treatment, to perform specific procedures, or to share management of chronic medical conditions.1,2 Efforts to revitalize the US primary care system through innovative models such as the patient-centered medical home3 focus on clarifying the relationship between PCPs and specialists and improving coordination between primary and specialty care.4,5

Besides serving as consultants or co-managers, some specialists also can serve as PCPs.6,7 Although specialists report providing primary care to a minority of their patients,8–11 it also has been proposed that specialists could serve as medical homes for patient populations with selected chronic medical conditions.12,13 Little is known regarding the types of patients who receive primary care from specialists, whether specialist PCPs provide the range of services and care coordination activities typically associated with primary care, or the quality of care delivered. Prior research shows that specialists are more likely to perform recommended care processes for a given medical condition within their area of expertise,14,15 but at a population level, a higher ratio of primary care physicians to specialists is associated with higher overall quality of care.16 Given anticipated shortages in generalist physicians,17,18 and diffusion of new models of primary care, a stronger understanding of the contribution of specialists to primary health care is needed.

In this study, we compare trends in patient and practice characteristics, and quality of care of visits to generalists and medical specialists self-identified as the patient’s primary care physician using data from an ongoing nationally representative sample of physician visits.

METHODS

Data Sources

We analyzed physician visits from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) from the years 1997–2010. Conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), NAMCS comprises a probability sample of office-based non-federally employed physicians who are principally involved in patient care activities, and is representative of physician office visits nationally.19

Data Collection Procedures

The NAMCS uses a three-stage probability sample design to obtain nationally representative samples of ambulatory visits. In the first stage, 112 primary sampling units (PSUs) are chosen, consisting of geographic segments within the United States. For the second stage, a sample of practicing physicians within each PSU is selected from the master files maintained by the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association. Finally, a random sample of patients seen during a pre-specified week is selected for each sampled physician.19 This design enables calculation of national-level estimates and associated standard errors using survey weights.

From 1997 to 2010, the physician response rate for NAMCS ranged from 58 to 71 %, with a range of 1,087 to 1,477 physician respondents per year. The number of visits sampled annually ranged from 20,760 to 32,778, for a total of 379,592 visits from 18,483 physicians over the time period 1997–2010. Data for each visit is collected using a standardized form and includes the patient’s primary reason for visit (i.e. chief complaint), up to three diagnoses derived from the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, Ninth Revision, patient demographic characteristics, and up to eight medications during the visit. From 2005 on, the prevalence of 12 chronic diseases was collected for all visits.20

Study Sample

We selected visits to generalists (family medicine, general internal medicine and general practice), internal medicine subspecialists (hereafter referred to as “medical specialists”), and obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs), but excluded visits to psychiatrists, neurologists and surgical specialists. Visits were excluded if the patient was under the age of 18 years, or if the reason for visit was pregnancy or prenatal care. We defined PCP visits as those in which the physician responded “yes” to the question “Are you the patient’s primary care physician?”

Outcomes

We first examined the proportion of visits in which the physician self-identified as the patient’s PCP for the years 1997–2010, to examine trends over time. For self-identified PCP visits, we examined patient characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, sex, and insurance status, practice characteristics including region, setting (urban vs. non-urban), and practice ownership, and visit characteristics including visit length. To assess the comprehensiveness of primary care, we examined the range of primary diagnoses,6 referral frequency, and reason for visit (new problem vs. chronic disease management, vs. preventive care). For these visit characteristics, we pooled visits across the study years for analyses.

Quality Measures

We examined a set of previously defined quality measures constructed using data from NAMCS21–23 for the years 1997–2010. The 24 measures include antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation, statin use for hyperlipidemia, inhaled corticosteroid for asthma, and mental health counseling or antidepressant use for depression, and use of inappropriate medications in the elderly.24 For each quality indicator, we identified the eligible population by examining the reason for visit and visit diagnoses (e.g. atrial fibrillation), and then identified those visits in which the appropriate quality metric was met (e.g. prescription of antithrombotic). Measures of overuse were defined in a similar manner.23 Indicators that had more than 30 % relative standard error (the standard error divided by the estimate, expressed as a percentage of the estimate) or a sample size of less than 30 cases per cell, were excluded per NCHS guidelines 19

Statistical Analysis

We constructed linear regression models for age and visit length, and logistic regression models for visit characteristics and quality indicators to examine differences by physician specialty. We also created multivariate models to adjust for calendar year, patient factors such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance, presence of co-existing conditions (atrial fibrillation, hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and depression), as well as visit type (new problem vs. chronic disease management, vs. preventive care), region, and location in a metropolitan area.

To assess trends in physician self-identification as PCP over time, we reported proportions of PCP visits for 2-year intervals. We then estimated a logistic regression model predicting physician self-identification as PCP in a given visit. We included physician specialty (generalist vs. medical specialist vs. OB/GYN), year as a linear term, and the interaction of specialty with year. We reported p values for the interaction of specialty and year.

All analyses were performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 11.0 (RTI International) to account for NAMCS’ complex multi-stage sampling design. The VA Boston Healthcare System institutional review board determined that this study was exempt from review.

RESULTS

Physician Specialty

From a total of 379,592 total visits included in NAMCS from 1997--2010, we identified a total of 141,010 visits to generalists, medical specialists and OB/GYNs. In 84,041 of these visits, representing an estimated 4.0 billion visits, the physician identified themselves as the patient’s PCP.

The proportion of medical specialist visits in which the physician indicated that they were the patient’s PCP decreased from 30.6 % in 1997 to 9.8 % in 2010 (Fig. 1, trend p < 0.01), but was stable for PCPs (88.7 %) and OB/GYNs (17.1 %). Cardiologists and pulmonologists less commonly self-identified as a PCP over time (Cardiology 34.9 % PCP visits in 1997 to 9.9 % PCP visits in 2010, p < 0.01, Pulmonary 35.0 % PCP visits in 1997 to 3.9 % PCP visits in 2010, p = 0.05). Infectious disease physicians (65.9 % PCP visits), nephrologists (44.8 % PCP visits), and endocrinologists (32.4 % PCP visits) commonly served as PCPs for their patients, and this was stable over time.

Figure 1.

Percentage of visits in which the physician self identifies as the patient’s PCP, by year.

Among the 84,041 visits to self-identified PCPs, most were to generalist physicians (91.5 %), with the remainder to medical specialists (5.8 %) and OB/GYNs (2.6 %). The proportion of PCP visits to generalists increased from 88.4 % in 1997 to 92.4 % in 2010, while the proportion of PCP visits to medical specialists decreased from 8.0 % to 4.8 % (p = 0.04) and the proportion of PCP visits to OB/GYNs was stable at 2.6 % (p = 0.53). Family practice was the most common speciality among visits to generalist PCPs, and cardiology was the most common specialty was among visits to medical specialist PCPs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Physician Specialty Among Visits to Generalist and Medical Specialist Self-Identified PCPs, 1997–2010

| Generalist (N = 74,611) | Medical Specialist (N = 6,620) |

|---|---|

| Family Practice (50.7 %) | Cardiology (26.2 %) |

| Internal Medicine (43.0 %) | Pulmonary (14.9 %) |

| General Practice (4.9 %) | Nephrology (11.7 %) |

| Internal Medicine/Geriatrics (0.6 %) | Hematology/Oncology (9.6 %) |

| Internal Medicine/Pediatrics (0.5 %) | Endocrinology (7.9 %) |

Patient Characteristics

Patients visiting medical specialist PCPs were older than those visiting generalist PCPs (61.0 vs. 55.4 years, p < 0.01) or OB/GYNs (38.3, p < 0.01, Table 1) and more frequently had Medicare insurance (Specialists 44.6 %, vs. 30.2 % generalists, vs. 5.5 % OB/GYNs, p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in patient race or ethnicity.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of Visits to Self-Identified PCPs 1997–2010, by Physician Specialty

| Generalist (n = 74,611) | Medical Specialist (n = 6,620) | OB/GYN (n = 2,810) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean) | 55.4 | 61.0 | 38.3 | <0.01 |

| Female | 59.2 % | 55.6 % | 100.0 % | <0.01 |

| Hispanic | 9.9 % | 11.9 % | 13.4 % | 0.12 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 84.8 % | 81.3 % | 81.4 % | |

| Black | 10.6 % | 11.5 % | 14.4 % | |

| Other | 4.7 % | 7.2 % | 4.2 % | 0.09 |

| Payer | ||||

| Private | 55.6 % | 44.2 % | 73.9 % | |

| Medicare | 30.2 % | 44.6 % | 5.5 % | |

| Medicaid | 6.5 % | 5.7 % | 12.8 % | |

| Other/self-pay | 7.8 % | 5.4 % | 7.8 % | <0.01 |

| Diagnoses† (2005–2010) | Generalist (n = 39,032) | Medical Specialist (n = 2,450) | OB/GYN (n = 1,336) | p* |

| Arthritis | 18.0 % | 18.0 % | 3.3 % | <0.01 |

| Asthma | 6.5 % | 8.2 % | 4.8 % | 0.13 |

| Cancer | 4.2 % | 12.7 % | 2.1 % | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 2.5 % | 4.4 % | 0.1 % | <0.01 |

| CHF | 2.8 % | 5.4 % | 0.0 % | <0.01 |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 1.7 % | 9.5 % | 0.0 % | <0.01 |

| COPD | 7.4 % | 7.4 % | 0.1 % | <0.01 |

| Depression | 13.3 % | 7.8 % | 6.2 % | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 17.7 % | 18.2 % | 4.2 % | <0.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 30.1 % | 26.5 % | 4.2 % | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 42.2 % | 43.8 % | 8.6 % | <0.01 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 5.2 % | 11.4 % | 0.5 % | <0.01 |

| Obesity | 11.6 % | 10.1 % | 7.8 % | 0.08 |

| Osteoporosis | 4.9 % | 6.3 % | 1.3 % | <0.01 |

| Total Chronic Diseases (mean) | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.5 | <0.01 |

* from logistic or linear regression adjusted for sample weights, with specialty as sole predictor

† prevalence of chronic disease is reported for years 2005–2010, where these data are present in NAMCS

CHF congestive heart failure; COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The prevalence of several chronic conditions was higher in visits to medical specialists than in visits to generalists, including congestive heart failure (CHF) (5.4 % of visits to medical specialists versus 2.8 % of visits to generalists, p < 0.01), cancer (12.5 % medical specialists, 4.2 %, generalists, p < 0.01) and ischemic heart disease (11.4 % specialists, 5.2 % generalists, p < 0.01). OB/GYN PCPs had few to no visits for patients with many chronic medical conditions including congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cerebrovascular disease. Depression was more common among visits to generalists than visits to medical specialists or OB/GYNs (13.3 % of generalist visits compared to 7.8 % of specialist visits, and 6.2 % OB/GYN visits p < 0.01). Patients visiting specialist PCPs had a higher mean number of chronic diseases when compared to those seeing generalist PCPs (2.0 chronic diseases for specialists vs. 1.7 for generalists, p < 0.01), but those visiting OB/GYN PCPs had fewer total chronic diseases (0.5 chronic diseases, p < 0.01 for both comparisons). Over time, visits to specialist PCPs were increasingly with older patients (p = 0.01, Online appendix Table 1).

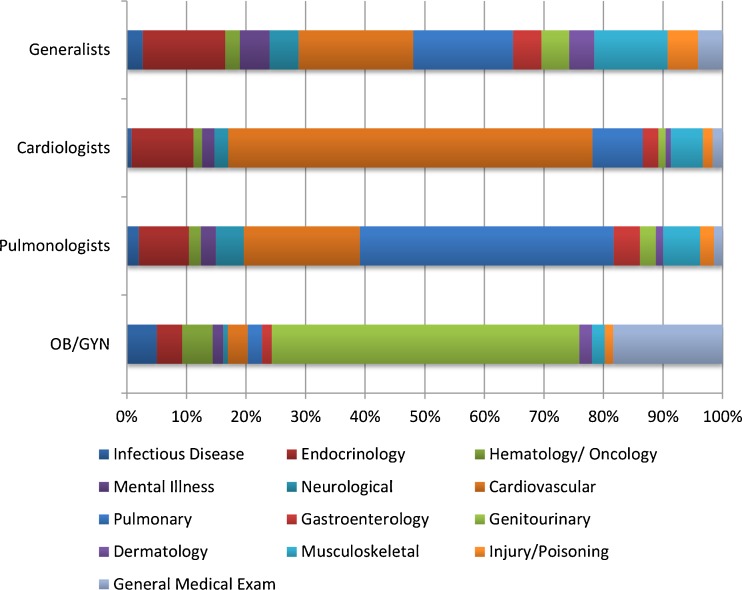

Diagnoses

Generalist PCPs saw a wide range of primary diagnosis clusters (Fig. 2), and visits were relatively distributed across these clusters. In contrast, the majority of visits to specialists PCPs (including OB/GYNs) were for diagnoses related to their specialty (e.g., 61.1 % of cardiologist PCP visits were for cardiovascular diagnoses).

Figure 2.

Diagnosis clusters for primary diagnosis in visits to self-identified PCPs from 1997 to 2010, by specialty.

Practice and Visit Characteristics

Visits to medical specialist PCPs were more common in the Northeast than in other regions of the United States (9.1 % of all PCP visits were to medical specialists in Northeast, vs. 3.8 % Midwest, 6.0 % South, and 5.0 % West, p < 0.01). Medical specialist and OB/GYN PCP visits were more common in urban settings (87.5 and 86.8 %, respectively, vs. 80.6 % of generalist visits, p < 0.01; Table 3). Medical specialist PCPs were more likely to be in solo practice and were more likely to be in physician owned practices than generalist PCPs or OB/GYN PCPs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Practice and Visit Characteristics of Visits to Self-Identified PCPs, 1997–2010, by Physician Specialty

| Generalist (n = 7,4611) | Medical Specialist (n = 6,620) | OB/GYN (n = 2,810) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | ||||

| Urban | 80.6 % | 87.5 % | 86.8 % | 0.01 |

| Solo practice | 37.9 % | 47.0 % | 30.7 % | 0.01 |

| Practice Ownership | <0.01 | |||

| Hospital | 7.8 % | 1.5 % | 7.4 % | |

| Physician Group | 79.5 % | 90.2 % | 83.9 % | |

| Other health care corporation | 7.4 % | 2.7 % | 4.2 % | |

| HMO | 2.2 % | 2.3 % | 1.3 % | |

| Other | 3.1 % | 3.3 % | 3.4 % | |

| Employment Status | <0.01 | |||

| Owner | 68.2 % | 82.8 % | 71.8 % | |

| Other (employee, contractor, other) | 31.8 % | 17.2 % | 28.2 % | |

| Visit length (mean, minutes) | 19.3 | 25.6 | 18.3 | 0.06 |

| Frequency of Referral (%) | 10.8 % | 7.4 % | 4.1 % | <0.01 |

| Established Patient (%) | 95.8 % | 96.9 % | 95.1 % | 0.02 |

| Type of Visit | <0.01 | |||

| New problem | 40.5 % | 26.9 % | 21.4 % | |

| Chronic Problem, Routine | 34.1 % | 51.0 % | 9.2 % | |

| Chronic Problem, Flare up | 9.2 % | 11.3 % | 4.5 % | |

| Pre/Post Surgery | 1.7 % | 2.1 % | 10.9 % | |

| Preventive Care | 14.5 % | 8.7 % | 54.0 % |

* from logistic or linear regression adjusted for sample weights, with specialty as sole predictor

HMO Health Maintenance Organization

Mean visit length was 19.3 minutes for visits to generalists, 25.6 minutes for visits to medical specialists, and 18.3 minutes for visits to OB/GYN PCPs. (p = 0.06, Table 3, adjusted p < 0.01 online appendix Table 3), and mean visit length increased over time for generalists and medical specialists (p < 0.01, online appendix Table 1). About 10.8 % of generalist visits resulted in referrals, as compared to 7.4 % of medical specialist visits, and 4.1 % of OB/GYN PCP visits (p < 0.01). The most common type of visit to generalists was for new problems (40.5 %), followed by routine management of chronic issues (34.1 %) and preventive care (14.5 %). The majority of visits to medical specialists were for management of chronic problems (51.0 %), followed by new problems (26.9 %). OB/GYN PCP visits were predominantly for preventive care (53.8 %), followed by new problems (21.6 %, p < 0.01). Differences in patient and visit characteristics among specialties were significant after adjusting for calendar year (online appendix Table 3) and trends over time are shown in online appendix Table 1.

Quality of Care

Table 4 summarizes comparisons of the quality of care among the different PCP specialties. The quality of cardiovascular care was higher in visits to cardiologist PCPs than in visits to generalist PCPs or other medical specialist PCPs (e.g. aspirin for coronary artery disease, 49.4 % for cardiologist visits, vs. 34.2 % for generalist visits, vs. 30.5 % other medical specialists p < 0.01; Table 4). For cardiovascular disease, visits to generalists had higher quality than visits to other medical specialist PCPs for use of beta-blockers in coronary artery disease (34.7 % generalists vs. 21.2 % other medical specialists, p = 0.05). OB/GYN PCPs did not have enough visits with relevant diagnoses (e.g. atrial fibrillation, CHF, coronary artery disease [CAD]) to allow comparison of cardiovascular or pulmonary quality. Visits to pulmonologists had higher rates of inhaled corticosteroid prescribing for asthma than generalist visits (37.5 % vs. 29.0 %, p = 0.03).

Table 4.

Adjusted Quality Indicator Performance Among Visits to Self-Identified PCPs, 1997–2010, by Physician Specialty*

| Cardiovascular care | Generalist | Cardiologist | Other medical specialist | p* |

| Antithrombotic therapy for AF | 59.1 % | 67.2 % | NS† | 0.17 |

| ACE/ARB use for CHF | 36.9 % | 46.9 % | 28.9 % | 0.08 |

| BB for CHF | 26.0 % | 37.6 % | 26.2 % | 0.06 |

| ASA for CAD | 34.2 % | 49.4 % | 30.5 % | <0.01 |

| BB for CAD | 34.7 % | 41.3 % | 21.2 % | 0.05 |

| Statin for CAD | 38.5 % | 47.3 % | 35.4 % | 0.05 |

| Statin for hyperlipidemia | 48.8 % | 59.9 % | 51.7 % | 0.05 |

| Statin for DM | 28.9 % | 36.0 % | 22.9 % | 0.08 |

| Pulmonary care | Generalist | Pulmonary | Other medical specialist | p |

| IH corticosteroid for asthma | 28.8 % | 37.5 % | NS | 0.03 |

| General medicine | Generalist | Medical Specialist | OB/GYN | p |

| BP check during GME | 86.8 % | 84.7 % | 83.2 % | 0.53 |

| Diet counseling during GME | 28.2 % | 31.1 % | 27.9 % | 0.75 |

| Exercise counseling during GME | 20.8 % | 21.2 % | NS | 0.50 |

| Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly | 9.7 % | 12.7 % | NS | <0.01 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 32.9 % | 29.5 % | 19.6 % | 0.20 |

| No benzodiazepines for depression | 82.2 % | 78.8 % | NS | 0.49 |

| Treatment of depression | 78.7 % | 70.6 % | NS | 0.09 |

| Treatment of osteoporosis | 47.5 % | 50.5 % | NS | 0.74 |

| Overuse | Generalist | Medical Specialist | OB/GYN | p |

| No routine CBC | 71.9 % | 73.4 % | 89.0 % | <0.01 |

| No routine urinalysis | 81.7 % | 86.2 % | 74.7 % | 0.01 |

| No routine EKG | 90.3 % | 87.4 % | NS | 0.28 |

| No antibiotics for URI | 55.1 % | 65.6 % | NS | 0.06 |

| No prostate cancer screening in men > 74 | 92.5 % | 94.4 % | NS | 0.14 |

| No routine X-ray | 94.9 % | 94.4 % | NS | 0.72 |

| No mammogram in women > 74 | 97.2 % | 97.1 % | NS | 0.85 |

| No pap in women > 65 | 96.8 % | NS | 52.9 % | <0.01 |

* from logistic regression adjusted for sample weights, with specialty as sole predictor

† NS signifies that there were insufficient visits to make valid comparisons

AF atrial fibrillation; ACE/ARB angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers; CHF Congestive heart failure; BB Beta blocker; ASA Aspirin; CAD coronary artery disease; DM diabetes mellitus ; IH Inhaled; BP blood pressure; GME general medical examination; CBC complete blood count; EKG electrocardiogram; URI upper respiratory infection

Visits to generalist had lower rates of inappropriate prescribing in the elderly than visits to specialists (9.7 % for generalists vs. 12.7 % for medical specialists, p < 0.01), and specialists performed more smoking cessation counseling than OB/GYNs (29.5 % vs. 19.6 %, p = 0.02). Other individual indicators of quality for general medical conditions were similar across the three groups (Table 4). Finally, indicators of overuse were similar between generalists and medical specialists, but OB/GYN PCP visits demonstrated higher rates of cervical cancer screening in elderly patients (no screening 52.9 % OB/GYN vs. 96.8 % generalists, p < 0.01). Over time, most cardiovascular quality measures improved for all specialties, blood pressure measurement during general medical exams increased for all specialties, and inappropriate prescribing for the elderly decreased for generalists and medical specialists (online appendix Table 2).23

DISCUSSION

In this study of national trends in the delivery of primary care by generalist and specialist physicians from 1997 through 2010, we demonstrate that generalist, medical specialist and OB/GYN PCPs perform different primary care roles for different populations. Generalist PCPs see the widest range of primary diagnoses, and most often see patients for new problems, suggesting they provide the most comprehensive primary care. OB/GYN PCPs see predominantly young women for preventive care and genitourinary complaints, while medical specialists predominantly see older patients for chronic disease management within their specialty. We also show that the proportion of visits in which medical specialists self-identify as the patient’s PCP has decreased markedly over time, suggesting medical specialists are less frequently serving as PCPs. Finally, we found that quality of care for conditions within the specialist’s domain was often higher than for visits to generalists, but that generalists provided similar or higher quality of care than specialists from other specialties.

In this analysis, we find that generalist PCPs tend to see more patients for new problems, suggesting that they more effectively serve as “first contact” for their patients with new concerns. They also see a wider range of symptoms and diagnoses in their visits, suggesting that they perform comprehensive care for a wider range of medical problems. Consistent with this finding, generalist PCPs also refer to other physicians more, which could suggest that they are more likely to serve a “triage” role, coordinating entry into the health care system for their patients. In contrast, specialist PCPs tend to see older patients who have a chronic condition within their specialty domain. They see fewer new complaints, see a more limited range of diagnoses, and perform less preventive care, suggesting they provide less comprehensive care than generalist PCPs. OB/GYN PCPs serve a unique role, in that they see young women, almost exclusively for preventive care and for genitourinary complaints, and only rarely serve as PCPs for older women with multiple chronic diseases.

We also demonstrate a dramatic decline over time in the proportion visits in which medical specialists serve as PCPs. The U.S. currently faces a shortage of generalist physicians due to the aging generalist workforce,25 earlier retirement among PCPs,26 and fewer students 27 and residents 17 pursuing careers in family medicine and general internal medicine. This shortage will be exacerbated as the U.S. population ages and as more people obtain insurance with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act.28 If there is further reduction in the primary care delivered by specialists, more patients will need to seek primary care from generalist physicians and as patients who see specialist PCPs are older, and have more serious medical conditions, this will increase the burden on generalist PCPs. These findings have important implications for primary care workforce projections.29

Prior studies have shown that specialists serve as PCPs for a small proportion of their patients.8 In contrast, we show that for some medical subspecialties, the proportion of visits in which the physician identifies as the patient’s PCP is high. Notably, in 65 % of infectious disease visits and in 44 % of nephrology visits, the physician considers himself or herself the patient’s PCP, and this has been stable over time. This suggests that for diseases such as HIV or chronic kidney disease, specialists are more likely to serve as PCPs, and these may be diseases for which specialist PCPs could serve as medical homes.9

There are several limitations to our work. First, we rely upon the physician self-report to identify PCP visits. Other methods such as direct reports from patients might have provided different estimates.30 Despite this, the question regarding PCP status has remained unchanged in NAMCS since 1997, suggesting that relative differences over time are likely to be representative of real changes. Second, measuring the quality of primary care is inherently challenging.31 Some have argued that the very essence of primary care; whole-person orientation, longitudinal care, and care coordination, is not adequately captured in disease specific quality metrics, leading to the “reductionist fallacy” that primary care is lower quality than specialty care.32 Additionally, in this visit-based assessment of primary care, we cannot assess longitudinal features of primary care such as continuity. Third, as the unit of analysis is an individual physician visit, we have no data on the potential co-management of disease among multiple physicians. Fourth, as the quality metrics available for use in NAMCS are based on a single visit, they rely heavily on accurate coding of all diagnoses, medications, and tests ordered in that visit. However, our observed proportions of visits achieving quality metrics are similar to those seen in other work.21–23 Finally, we tested for linear trends over time in the proportion of visits in which the PCP self-identifies as a PCP, which may not capture non-linear changes over time.

In conclusion, generalist, medical specialist and OB/GYN PCPs serve different roles. Generalist PCPs see the widest range of diagnoses and serve more often as the first contact for new problems, suggesting they provide the most comprehensive primary care. Medical specialists and OB/GYN PCPs see more limited patient populations for more focused functions. Efforts to design new models of primary care should account for the unique roles of specialist PCPs and for the decreasing role of medical specialists in providing primary care.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 52 kb)

(DOCX 54 kb)

(DOCX 51 kb)

(DOCX 49 kb)

Acknowledgements

Steven R. Simon, MD provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

This study was presented in abstract form at the Society for General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Denver CO, 24–27 April 2013, and at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, Baltimore, MD, 23–35 June 2013.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Funding

Dr. Edwards was supported by the Massachusetts Veteran’s Epidemiology Research and Information Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA. Dr. Mafi was supported by a National Research Service Award training grant T32HP12706 from the US Health Services and Research Administration and by the Ryoichi Sasakawa Fellowship Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest CB. A typology of specialists’ clinical roles. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1062–1068. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitton A. Who is on the home team? Redefining the relationship between primary and specialty care in the patient-centered medical home. Med Care. 2011;49(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820313e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pham HH. Good neighbors: how will the patient-centered medical home relate to the rest of the health-care delivery system? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):630–634. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1208-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279(17):1364–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken LH, Lewis CE, Craig J, Mendenhall RC, Blendon RJ, Rogers DE. The contribution of specialists to the delivery of primary care. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(24):1363–1370. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casalino LP, Rittenhouse DR, Gillies RR, Shortell SM. Specialist physician practices as patient-centered medical homes. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1555–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1001232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholle SH, Chang J, Harman J, McNeil M. Characteristics of patients seen and services provided in primary care visits in obstetrics/gynecology: data from NAMCS and NHAMCS. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4):1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kale MS, Federman AD, Ross JS. Visits for primary care services to primary care and specialty care physicians, 1999 and 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2012;1–2. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Forrest CB, Sibbald B, Roland M. Ambulatory care provided by office-based specialists in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):104–111. doi: 10.1370/afm.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirschner N, Barr MS. Specialists/subspecialists and the patient-centered medical home. Chest. 2010;137(1):200–204. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berenson RA. Is there room for specialists in the patient-centered medical home? Chest. 2010;137(1):10–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrold LR, Field TS, Gurwitz JH. Knowledge, patterns of care, and outcomes of care for generalists and specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(8):499–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.08168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smetana GW, Landon BE, Bindman AB, et al. A comparison of outcomes resulting from generalist vs specialist care for a single discrete medical condition: a systematic review and methodologic critique. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):10–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4–184–97. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs. subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241–2247. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.47535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American College of Physicians. The Impending Collapse of Primary Care Medicine and Its Implications for the State of the Nation’s Health Care. January 30, 2006 Philadelphia. Accessed at http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/advocacy_in_action/state_of_the_nations_healthcare/assets/statehc06_1.pdf on 3 Feb 2014

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. National Ambulatory Medical Survey, 1997-2010. Public-use data file and documentation. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm Accessed 29 Sept 2013.

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics, ed. NAMCS Patient Record Form 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/NAMCS_30A_2010.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2013.

- 21.Ma J, Stafford RS. Quality of US outpatient care: temporal changes and racial/ethnic disparities. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(12):1354–1361. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linder JA, Ma J, Bates DW, Middleton B, Stafford RS. Electronic health record use and the quality of ambulatory care in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1400–1405. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kale MS, Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Trends in the overuse of ambulatory health care services in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):142–148. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1531–1536. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440350031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011. 2011 State Physician Workforce DataBook. Center for Workforce Studies,. Accessed at www.aamc.org/download/263512/data/statedata2011.pdf on 3 Feb 2014.

- 26.Lipner RS, Bylsma WH, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Tooker J, Cassel CK. Who is maintaining certification in internal medicine–and why? A national survey 10 years after initial certification. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(1):29–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips J, Weismantel D, Gold K, Schwenk T. How do medical students view the work life of primary care and specialty physicians? Fam Med. 2012;44(1):7–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colwill JM, Cultice JM, Kruse RL. Will generalist physician supply meet demands of an increasing and aging population? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):w232–w241. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010–2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503–509. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiegel JS, Rubenstein LV, Scott B, Brook RH. Who is the primary physician? N Engl J Med. 1983;308(20):1208–1212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198305193082007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyweide DJ, Weeks WB, Gottlieb DJ, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. Relationship of primary care physicians’ patient caseload with measurement of quality and cost performance. JAMA. 2009;302(22):2444–2450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293–299. doi: 10.1370/afm.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 52 kb)

(DOCX 54 kb)

(DOCX 51 kb)

(DOCX 49 kb)