Abstract

Background/Aims

Patients with cholangiocarcinoma usually present at an advanced stage, and more than 50% of cases are not resectable at the time of diagnosis. Recently, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been proposed as a palliative and neoadjuvant modality. We evaluated whether combination of PDT and chemotherapy is more effective than PDT alone.

Methods

In total, 161 patients with cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed between February 1999 and September 2009 were evaluated. Sixteen patients were treated with PDT and chemotherapy (group A), and 58 were treated with PDT (group B).

Results

The median survival was 538 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 475.3 to 600.7) in group A and 334 days (95% CI, 252.5 to 415.5) in group B (p=0.05). Lymph node metastasis status, serum bilirubin of pretreatment, tumor node metastasis stage, treatment method (PDT with chemotherapy vs PDT alone), time to PDT and the number of PDT sessions were prognostic factors with statistical significance in the univariate analysis. A multivariate analysis showed that PDT with chemotherapy and more than two sessions of PDT were significant independent predictors of longer survival in advanced cholangiocarcinoma (hazard ratio [HR], 2.23; 95% CI, 1.18 to 4.20; p=0.013 vs HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.044 to 3.083; p=0.034).

Conclusions

PDT with chemotherapy results in longer survival than PDT alone.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Photochemotherapy, Drug therapy

INTRODUCTION

Bile duct cancer is uncommon accounting for less than 2% of all human malignancies. Approximately 60% of bile duct cancers involve the biliary confluence.1 Complete resection with negative margins is the only treatment with a potential cure, and 5-year survival rates are 20% to 40%.2,3 Even among the 5-year survivors, a significant number will eventually succumb to the disease.3,4,5 Patients usually present at an advanced stage, with more than 50% of cases being unresectable at the time of diagnosis.6 As a result, a large proportion of patients is beyond the scope of curative treatment upon diagnosis, getting only palliative managements.7,8,9

Recently, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been evaluated as a palliative and neoadjuvant modality. Two randomized controlled trials have shown a significant survival benefit from PDT in patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma.10,11 Although PDT therapy has been shown to increase survival, there was a limitation of local therapy. Some studies of chemotherapy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma were reported. However, they did not show a definite effect on survival until recently. Recently, a study with gemcitabine based chemotherapy has promising effect of survival gain in advanced cholangiocarcinoma.12

It is not known whether a combination of PDT, local therapy, and systemic chemotherapy is effective treatment. The primary aim of our study was to examine the survival gain with the therapy of PDT and systemic chemotherapy compared to PDT therapy alone in patients with advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The secondary aim was to evaluate the prognostic factors related with survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

A total of 161 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed between February 1999 and September 2009 were evaluated. Exclusion criteria were that surgery had been performed, Karnofsky performance status of <60, loss of follow-up, and sudden death during diagnostic workup. Thus, data of 74 patients were available for analysis. Patients were divided into group A and B according to the treatment modality. Sixteen were treated with PDT and gemcitabine with or without cisplatin (group A) and 58 were treated with PDT only (group B). All patients included in this study were believed to be unresectable by accepted criteria.13,14 The Institutional Review Board of our hospital approved this study.

2. Photodynamic therapy and gemcitabine or/and cisplatin

PDT is a two step procedure. A photosensitizing drug known to preferentially accumulate in tumor cells is administered, and the tumor is exposed to nonthermal laser light of the appropriate photoactivating wavelength after a time interval required for the drug to accumulate in tumor tissue. Porphyrin-based photosensitizers, such a hematoporphyrin derivatives and its partly purified commercial preparation, porfimer sodium, are the most commonly used sensitizers. Photofrin accumulates in cholangiocarcinoma cells with a tumor to a normal tissue fluorescence ratio of 2 to 1, 24 and 48 hours after administration.15 Patients received porfimer sodium intravenous at a dose of 2 mg/kg 4 hours before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopy (PTCS) photoradiation. To perform the percutaneous PDT procedure, a guidewire was first inserted throughout the stricture into the common bile duct. A 6-Fr guiding catheter was then inserted along the guidewire, permitting the guidewire to be removed. A diffuser fiber was then inserted through the guiding catheter and the stricture site was irradiated from the distal to the proximal region under cholangioscopy and fluoroscopy. To perform PDT with ERCP, the preloaded catheter was advanced across the bile duct tumor using a 0.035 inch guidewire. The tip of the catheter contained a metal marker and was cut just below this marker to allow the fiber to pass. Tumor segments were treated sequentially in a proximal to distal fashion. After PDT was performed, 10-Fr plastic biliary stents were inserted to ensure adequate decompression and bile drainage.

PDT was repeated in cases of tumor progression, when subsequent biopsies from the hilar stenosis were positive, or when increased tumor thickness was evident on follow-up percutaneous cholangioscopy or intraductal ultrasonography scans.

Biliary drainage was applied to prevent cholestasis before chemotherapy. Chemotherapy used mainly gemcitabine single or gemcitabine with cisplatin. We excluded five patients with FP regimen (5-FU and cisplatin) in this study.

3. Statistical analysis

Numerical data are presented as the median with range. Data for patients with PDT alone and systemic chemotherapy with PDT were compared with respect to demographic, clinical, and treatment variables using Pearson chi-square test and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Estimates of probabilities of survival for the follow-up study were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Data were summarized by the median and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For survival rates, deaths unrelated to cholangiocarcinoma, such as cardiovascular events, were treated as censored patients. Survival was calculated from the day of diagnosis until death or the last follow-up.

Cox regression was used to determine independent predictors of outcome, using survival as the dependent variable and significant factors (p<0.15) by univariate analysis as the independent variables. The p-values of ≤0.05 were deemed to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

1. Patients

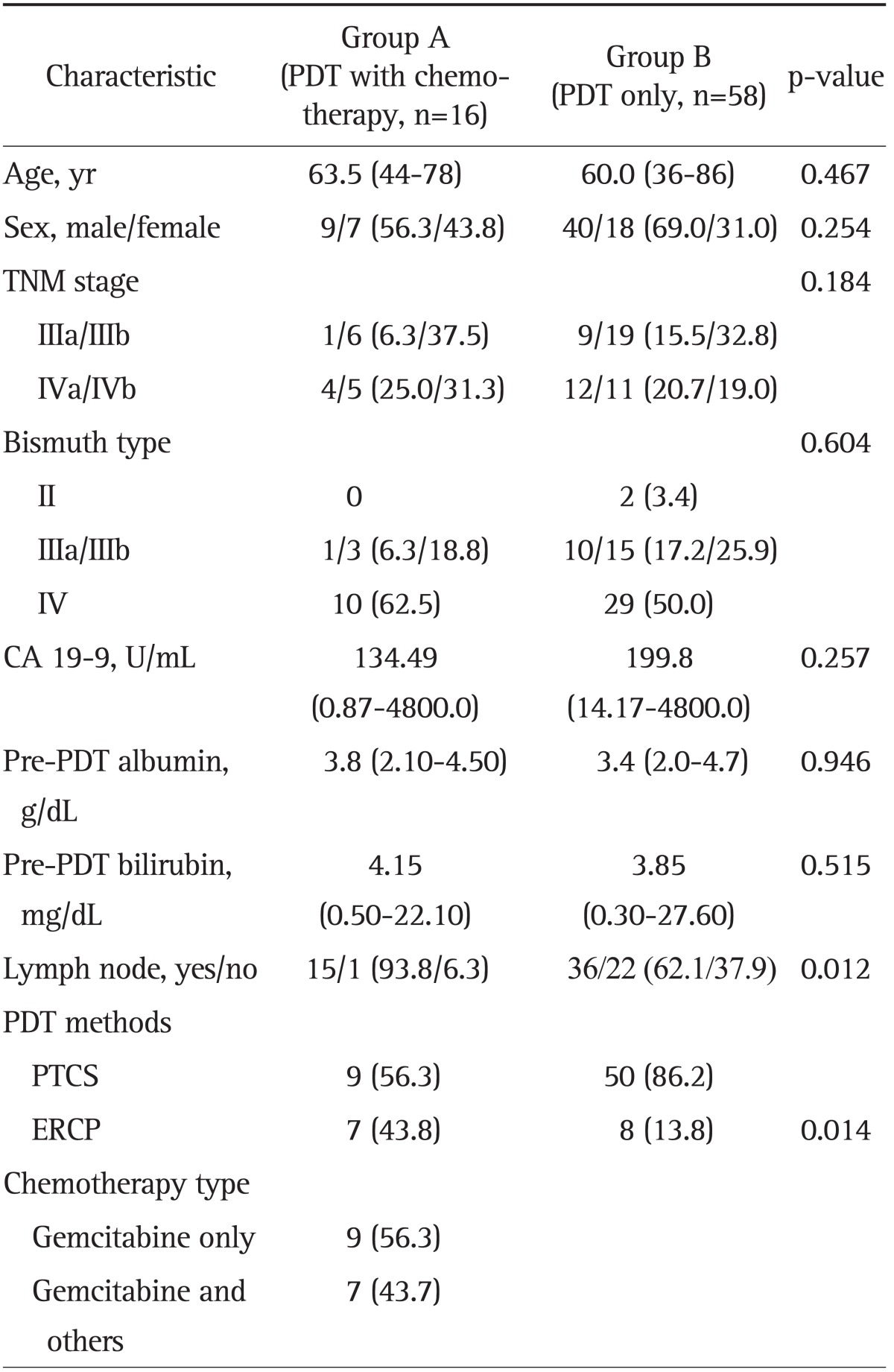

Baseline characteristics were shown in the Table 1. Two groups were similar except in lymph node metastasis and frequency of ERCP in PDT method. Lymph node metastasis was more frequent in group A (15/16, 93.8%) than in group B (36/58, 62.1%) (p=0.012). Among PDT methods, the frequency of ERCP was higher in group A than B (43.8% vs 13.8%, p=0.014). There was no difference in age, sex, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, bismuth type, CA 19-9 level, and pre-PDT albumin level between two groups. In the group A, nine patients were treated with gemcitabine single (56.3%) with median 3 cycles (range, 2 to 5 cycles), and six patients were received gemcitabine with cisplatin (43.7%) with median 6 cycles (range, 4 to 7 cycles). Among patients with PDT, 52 patients (70.3%) received only one PDT and the rest (29.7%) did PDT of more than two.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the 74 Patients with Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma

Data are presented as median (range) or number (%).

PDT, photodynamic therapy; TNM, tumor node metastasis; PTCS, percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

2. Survival between PDT alone and systemic chemotherapy with PDT

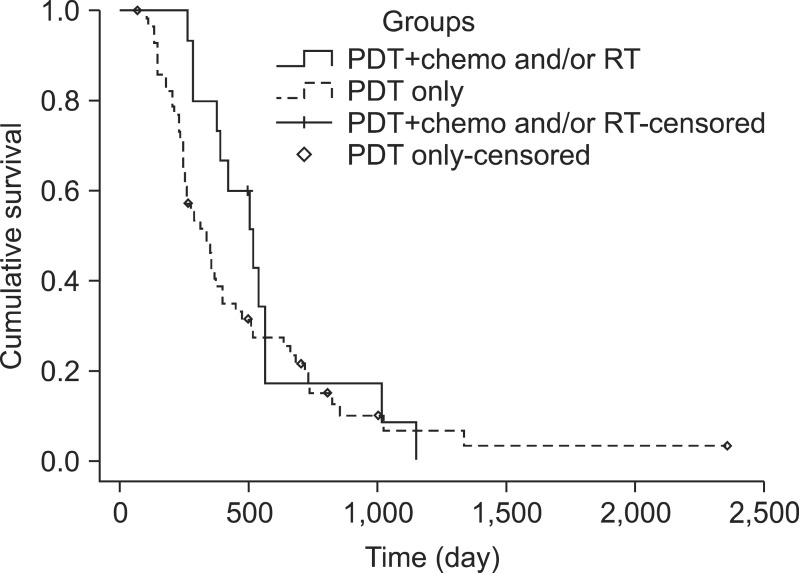

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that group A (PDT with chemotherapy) has a higher survival rate than group B (PDT only) (Fig. 1). The overall median survival time was 17.9 months (95% CI, 12.0 to 22.4) of group A and 11.1 months (95% CI, 8.4 to 13.8) of group B (p=0.05). The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates were 93%, 16%, and 0% in group A and 40%, 17%, and 3% in group B, respectively. Patients in group A survived longer than in group B on the 1-year survival rate, but there was no difference in 2- and 3-year survival rates.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier graph demonstrating the cumulative survival of group A treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT) with chemotherapy (unbroken line) and group B with PDT only (dotted line). In the PDT with chemotherapy group (n=16), the median survival time was 17.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.8 to 20.0 months). In the PDT alone group (n=58), the median survival period was 11.1 months (95% CI, 8.4 to 13.9 months; p=0.05).

RT, radiotherapy.

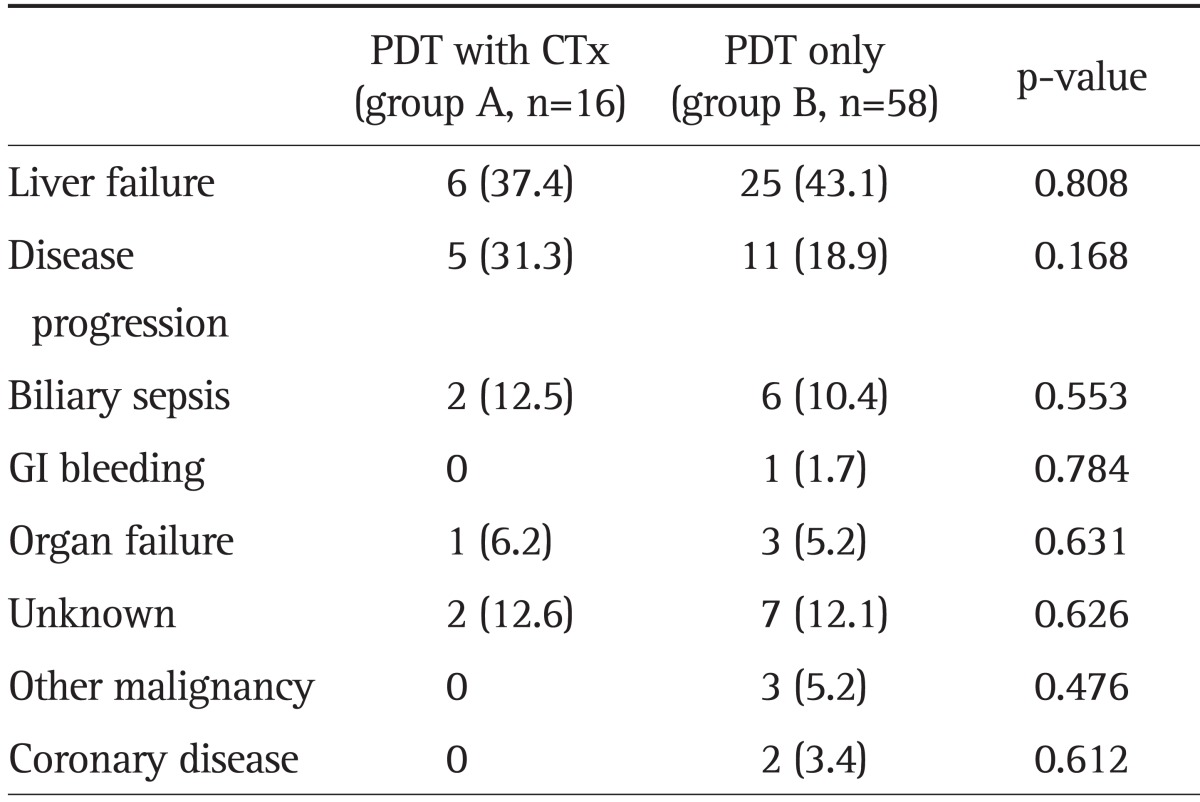

At the end of follow-up period, all patients of group A and B had died. The most common cause of death in both groups was liver failure (37.4%, n=6 in group A; 43.1%, n=25 in group B; p=0.808), followed by disease progression (31.3%, n=5 in group A; 18.9%, n=11 in group B; p=0.168) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Causes of Death in the 74 Treated Patients

Data are presented as number (%).

PDT, photodynamic therapy; CTx, chemotherapy; GI, gastrointestinal.

3. Prognostic factors for survival

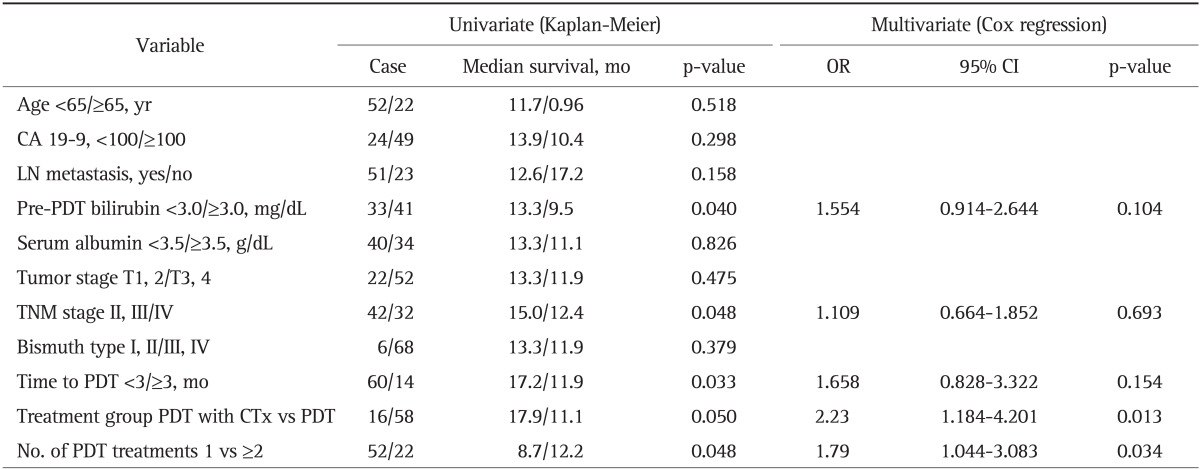

Table 3 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analysis of all variables related with survival in all patients. Less than 3.0 mg/dL of pre-PDT serum bilirubin level (p=0.040), less than III stage of TNM (p=0.048), the case of PDT within 3 months from diagnosis (p=0.033), repeated PDT of more than two, and PDT with chemotherapy (p=0.05) were significant prognostic factors in the univariate analysis. However, age, level of CA 19-9, lymph node metastasis, serum albumin level of pretreatment, and bismuth type did not show statistical significance as a prognostic factor in the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis using Cox regression showed that PDT with chemotherapy and reduplicative PDT were significant independent predictors of longer survival in advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma (hazard ratio [HR], 2.23; 95% CI, 1.18 to 4.20; p=0.013 vs HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.044 to 3.083; p=0.034) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Potential Prognostic Factors for the Survival Rate in Patients with Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LN, lymph node; PDT, photodynamic therapy; TNM, tumor node metastasis; CTx, chemotherapy.

4. Treatment-related complications

Early complications (cholangitis) were experienced by one patient (6.3%) in the group A and three patients (5.2%) in the group B. Of PDT-specific adverse events, two patients in group B experienced dermal phototoxicity. Liver abscess occurred in two patients (3.4%) in the group B. These patients had an external biliary drainage tube. With respect to complications related to the PTCS tube, one patient had tube breakage, two patients had bile leakage from the tube insertion site, and two patients had premature exchange of the PTCS tube due to early tube occlusion.

DISCUSSION

Complete surgical resection remains the foundation of curative intent therapy for patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, but due to its anatomic location and natural history, the disease locally advanced in most patients at the time of diagnosis. Patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma have limited therapeutic options other than palliative biliary stenting. Although metal stent insertion improves occlusion rates and reduces the number of therapeutic interventions, median survival time is not ameliorated.16 Radiotherapy (RT) or chemotherapy attempt to affect tumor growth. To date, however, no randomized prospective study concerning the effect of these long-used additional therapies is available. The only retrospective comparative study of palliative radiation therapy showed no significant improvement in median survival time between endoscopic biliary stenting alone or additional external-beam RT and internal brachytherapy with 192-iridium (300 days vs 210 days).17 Recently, a prospective study of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer provided evidence that cisplatin plus gemcitabine was an effective treatment option for locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer.12 In this study, the median overall survival was 11.7 months in the cisplatin-gemcitabine group and 8.1 months in the gemcitabine group (p<0.001). However, the overall median survival in the cisplatin-gemcitabine group was not longer than previous results of palliative biliary drainage only.12,18 One limitation of this randomized study was a heterogeneous group that included gall bladder and ampullary cancer in addition to bile duct cancer.

A treatment modality for local ablation of the primary tumor could improve the outcome of curative and palliative therapies. Palliative brachytherapy with 192-iridium alone (35 Gy at 1-cm distance) did not prolong median survival time (4.3 to 5 months)19 but, when combined with external beam RT (30 Gy), did result in median survival times of 10 to 10.5 months.17 Another modality for local tumor ablation of cholangiocarcinoma is PDT. Even in patients with advanced disease, PDT has been shown to improve survival, quality of life, and performance status compared with biliary stenting in uncontrolled20,21 and randomized controlled trials.11,12 The median survival after PDT in our study was 11.5 months, which was similar to the results of randomized controlled trials with chemotherapy.22 PDT is based on the relatively specific accumulation of photosensitizers, such as porphyrins, in dysplastic or malignant cells. After intravenous, oral, or topical applications, the photosensitizer drug predominantly concentrates in tumor tissue and remains inactive until exposed to a specific wavelength of light. When light is delivered to the target cancer site, the photodynamic reaction induces photochemical destruction of tumor tissue mediated by singlet molecular oxygen and other active species generated by the reaction of the activated photosensitizer and mucosal oxygen. Damage to tissue occurs by several pathways including cell necrosis, apoptosis and ischemia with vascular shutdown.6

The survival of the PDT with chemotherapy group tended to be greater than the PDT-alone group in our study. The median survival length was 17.9 months (95% CI, 12.0 to 22.4) of PDT with chemotherapy and 11.1 months (95% CI, 8.4 to 13.8) of PDT alone (p=0.05). Additional PDT (i.e., local ablative therapy) and systemic chemotherapy may create a synergistic effect that improves the survival and quality of life in advanced bile duct cancer. The local tumor control is important prognostic factor in advanced hilar bile duct cancer. In the majority of patients with tumor stenosis in the distal and middle part of the bile duct cholestasis can be relieved quickly. Palliative intervention is limited in proximal bile duct cancers. A successful drainage (bilirubin decrease >30% to 50%) is only achieved, however, in 69% to 91% of Bismuth type I and II stenosis and 15% to 73% in Bismuth type III and IV tumors. This is reflected in the survival time of these patients: 149 to 160 days for Bismuth type I, 84 to 131 days for Bismuth type II, and 62 to 70 days for Bismuth type III strictures.23,24 Attempts to control tumor growth are made with PDT and additional systemic chemotherapy has certain benefit to improve the survival in advanced hilar bile duct cancer.

Our previous exam suggested that PDT in advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma should be repeated every 3 months because mean thickness of the mass had increased at 4 months after PDT.21 This study showed that patients with several times of PDT survived longer than those with single PDT in the univariate analysis (median survival length, 12.2 months vs 8.7 months; p=0.048). We expected that PDT of several sessions, at least twice, could improve the survival of advanced cholangiocarcinoma patients.

Pre-PDT serum bilirubin level, less than III stage of TNM, shorter time to PDT from diagnosis, repeated PDT, and PDT with chemotherapy were good prognostic factors with statistical significance in the univariate analysis in all patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma. On the multivariate analysis, PDT with chemotherapy and PDT of several times were significant predictors of survival.

Because it was retrospective and small sample size of PDT and chemotherapy group compared with PDT alone, this study is limited. However, this study population was derived from a larger cohort of patients with cholangiocarcinoma and follow-up exceeded 1 year. Median survival of this cohort was comparable to that of other cohorts reported in the literature. However, further prospective randomized controlled studies between chemotherapy and/or RT with PDT and chemotherapy alone will be needed to confirm the role of PDT in advanced bile duct cancer.

In summary, repeated PDT with systemic chemotherapy resulted in longer survival than PDT only or a single PDT. Additional PDT to systemic chemotherapy seems to be a promising new approach to hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Carriaga MT, Henson DE. Liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and pancreas. Cancer. 1995;75(1 Suppl):171–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<171::aid-cncr2820751306>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rea DJ, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell MB, et al. Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:514–523. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang JY, Kim SW, Park DJ, et al. Actual long-term outcome of extrahepatic bile duct cancer after surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2005;241:77–84. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150166.94732.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Werner M, Weimann A, Pichlmayr R. What constitutes long-term survival after surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma? Cancer. 1997;79:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheon YK. The role of photodynamic therapy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:345–352. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumgart LH, Stain SC. Surgical treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Treat Res. 1994;69:75–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2604-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeek PC, Van der Heyde MN, Ramsoekh T, Bosma A. Clinical significance of implantation metastases after surgical treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1990;10:142–144. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pichlmayr R, Lamesch P, Weimann A, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment of cholangiocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 1995;19:83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00316984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold JC, Apel D, Riemann JF. Palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer: improved survival after photodynamic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2426–2430. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortner ME, Caca K, Berr F, et al. Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385–394. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vauthey JN, Blumgart LH. Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:109–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pahernik SA, Dellian M, Berr F, Tannapfel A, Wittekind C, Goetz AE. Distribution and pharmacokinetics of Photofrin in human bile duct cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;47:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(98)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340:1488–1492. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowling TE, Galbraith SM, Hatfield AR, Solano J, Spittle MF. A retrospective comparison of endoscopic stenting alone with stenting and radiotherapy in non-resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Gut. 1996;39:852–855. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ducreux M, Liguory C, Lefebvre JF, et al. Management of malignant hilar biliary obstruction by endoscopy: results and prognostic factors. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:778–783. doi: 10.1007/BF01296439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molt P, Hopfan S, Watson RC, Botet JF, Brennan MF. Intraluminal radiation therapy in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. Cancer. 1986;57:536–544. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<536::aid-cncr2820570322>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berr F, Wiedmann M, Tannapfel A, et al. Photodynamic therapy for advanced bile duct cancer: evidence for improved palliation and extended survival. Hepatology. 2000;31:291–298. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shim CS, Cheon YK, Cha SW, et al. Prospective study of the effectiveness of percutaneous transhepatic photodynamic therapy for advanced bile duct cancer and the role of intraductal ultrasonography in response assessment. Endoscopy. 2005;37:425–433. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM. "Natural history" of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:425–429. doi: 10.4065/70.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polydorou AA, Cairns SR, Dowsett JF, et al. Palliation of proximal malignant biliary obstruction by endoscopic endoprosthesis insertion. Gut. 1991;32:685–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.6.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354–362. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]