Abstract

Mutations in hemojuvelin (HJV) are the most common cause of the juvenile-onset form of the iron overload disorder hereditary hemochromatosis. The discovery that HJV functions as a co-receptor for the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family of signaling molecules helped to identify this signaling pathway as a central regulator of the key iron hormone hepcidin in the control of systemic iron homeostasis. This review highlights recent work uncovering the mechanism of action of HJV and the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway in regulating hepcidin expression in the liver, as well as additional studies investigating possible extra-hepatic functions of HJV. This review also explores the interaction between HJV, the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway and other regulators of hepcidin expression in systemic iron balance.

Keywords: hemojuvelin, bone morphogenetic protein, hepcidin, iron, hemochromatosis, repulsive guidance molecule

Juvenile hemochromatosis is caused by mutations in the genes encoding hepcidin or hemojuvelin

Juvenile Hemochromatosis (JH) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a failure to prevent excess iron entry into the bloodstream, and characterized by progressive tissue iron overload (Pietrangelo, 2010). Although iron's redox properties are critical for its role in many fundamental biological processes from cellular respiration to oxygen transport, iron excess can lead to toxic free radical generation. If left untreated, JH patients develop multiorgan dysfunction as a consequence of iron overload, including cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, diabetes mellitus, and hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, before the age of 30 (Pietrangelo, 2010).

The identification of hepcidin as a master regulator of systemic iron balance was a major advance in understanding the pathophysiology of JH (Ganz, 2013). A defensin-like peptide produced predominantly by hepatocytes, hepcidin controls iron entry into the bloodstream from dietary sources, recycled red blood cells, and body storage sites by inducing degradation of the iron exporter ferroportin (Ganz, 2013). Hepcidin expression is stimulated by iron and inflammation to limit iron availability, while hepcidin is inhibited by iron deficiency, anemia, and hypoxia to increase iron availability for erythropoiesis (Babitt and Lin, 2010; Ganz, 2013). Hepcidin deficiency is the common pathogenic mechanism underlying both adult and juvenile-onset hemochromatosis and contributes to the pathogenesis of iron loading anemias such as thalassemia, while its overproduction causes anemia of inflammation and iron refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) (Ganz, 2013). JH is caused by mutations in the gene encoding hepcidin itself (HAMP) or, more commonly, hemojuvelin (HJV, also known as HFE2 or RGMC) (Roetto et al., 2003; Papanikolaou et al., 2004).

HJV encodes a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked membrane protein that is a member of the repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) family (Monnier et al., 2002; Samad et al., 2004). Currently, there are 43 identified HJV mutations that cause JH, with G320V being the most frequent (Table 1). HJV is expressed in the liver, and JH patients with HJV mutations and Hjv knockout mice exhibit significantly reduced hepatic hepcidin expression, thereby implicating HJV in the regulation of hepcidin synthesis (Papanikolaou et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2005; Niederkofler et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Mutations of the HJV gene linked to JH.

| Residue mutation | Exon | Type of mutation | Nucleotide change | Family origin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q6H | 2 | Missense | 18G > C | Asian | Huang et al., 2004 |

| L27fsX51 | 2 | Frame shift | 81delG | English/Irish | Wallace et al., 2007 |

| R54X | 3 | Nonsense | 160A > T | African American | Murugan et al., 2008 |

| G66X | 3 | Nonsense | 196G > T | Romanian | Jánosi et al., 2005 |

| V74fsX113 | 3 | Frame shift | 220delG | English | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| C80R | 3 | Missense | 238T > C | Caucasian | Lee et al., 2004 |

| S85P | 3 | Missense | 253T > C | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| G99R | 3 | Missense | 295G > A | Albanian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| G99V | 3 | Missense | 296G > T | Multiple | Papanikolaou et al., 2004; Silvestri et al., 2007 |

| L101P | 3 | Missense | 302T > C | Albanian | Lanzara et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2004 |

| G116X | 3 | Nonsense | Santos et al., 2012 | ||

| C119F | 3 | Missense | G356 > T | German | Gehrke et al., 2005; Silvestri et al., 2007 |

| R131fsX245 | 3 | Frame shift | 391-403del | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| D149fsX245 | 3 | Frame shift | 445delG | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| L165X | 3 | Nonsense | 494T > A | van Dijk et al., 2007 | |

| A168D | 3 | Missense | 503C > A | Australian /English | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| F170S | 3 | Missense | 509T > C | Italian | De Gobbi et al., 2002; Lanzara et al., 2004; Silvestri et al., 2007 |

| D172E | 3 | Missense | 516C > G | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| R176C | 3 | Missense | 526C > T | European | Aguilar-Martinez et al., 2007; Ka et al., 2007 |

| W191C | 3 | Missense | 573G > T | Italian | De Gobbi et al., 2002; Lanzara et al., 2004; Silvestri et al., 2007 |

| N196K | 3 | Missense | 588T > G | Santos et al., 2012 | |

| S205R | 3 | Missense | 615C > G | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| I222N | 4 | Missense | 665T > A | Canadian | Papanikolaou et al., 2004 |

| K234X | 4 | Nonsense | 700-703AAG del | European | Santos et al., 2012 |

| D249H | 4 | Missense | 745G > C | Asian | Santos et al., 2012 |

| G250V | 4 | Missense | 749G > T | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| N269fsX311 | 4 | Frame shift | 806 > 807insA | English | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| I281T | 4 | Missense | 842T > C | Multiple | Huang et al., 2004; Papanikolaou et al., 2004 |

| C282Y | 4 | Missense | Caucasian | Le Gac et al., 2004 | |

| R288W | 4 | Missense | 863C > T | French | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| R288Y | 4 | Missense | 862C > T | Wallace et al., 2007 | |

| E302K | 4 | Missense | 904G > A | Brazilian | Santos et al., 2011 |

| A310G | 4 | Missense | 929C > G | Brazilian | de Lima Santos et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2011 |

| Q312X | 4 | Nonsense | 934C > T | Asian | Nagayoshi et al., 2008 |

| G319fsX341 | 4 | Frame shift | 954-955insG | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004 |

| G320V | 4 | Missense | 959G > T | Multiple | Lanzara et al., 2004; Papanikolaou et al., 2004; Gehrke et al., 2005; Silvestri et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2011 |

| C321W | 4 | Missense | 963C > G | European | Wallace et al., 2007 |

| C321X | 4 | Nonsense | 962G > A, 963C > A | Asian | Huang et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2012 |

| R326X | 4 | Nonsense | 976C > T | Asian | Huang et al., 2004; Papanikolaou et al., 2004 |

| S328fsX337 | 4 | Frame shift | 980-983 delTCTC | Slovakian | Gehrke et al., 2005 |

| R335Q | 4 | Missense | 1004G > A | Wallace et al., 2007 | |

| C361fsX366 | 4 | Frame shift | 1080delC | European | Papanikolaou et al., 2004 |

| N372D | 4 | Missense | 1114A > G | Wallace et al., 2007 | |

| R385X | 4 | Nonsense | 1153C > T | Italian | Lanzara et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2012 |

BMP-SMAD signaling via HJV is a central regulator of hepcidin

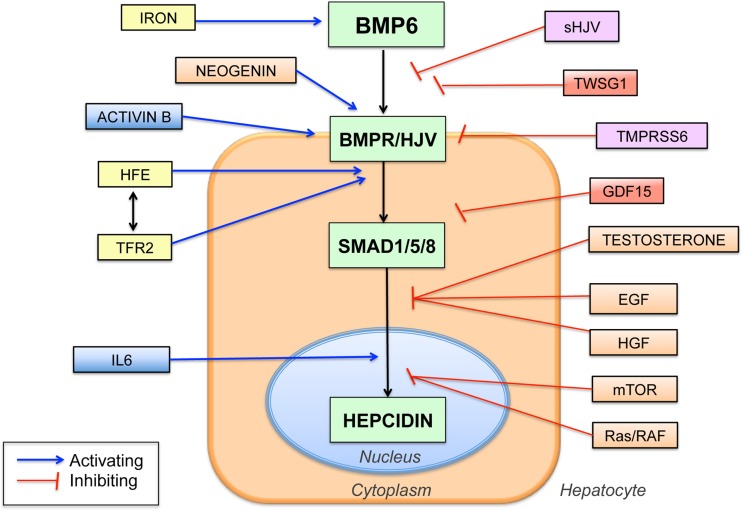

A breakthrough in understanding the mechanism of action of HJV in hepcidin regulation came when HJV was discovered to function as a co-receptor for the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway (Babitt et al., 2006), analogous to its RGM family homologs (Babitt et al., 2005; Samad et al., 2005). Importantly, this BMP signaling function of HJV was demonstrated to be crucial for its role in regulating hepcidin expression (Babitt et al., 2006) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing the central role of the BMP6-HJV-SMAD signaling pathway in hepcidin regulation and the proposed interaction with other hepcidin regulators. BMP6 binds to the BMP type I and type II receptors (BMPR) and the co-receptor HJV to increase phosphorylation of SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8 proteins (SMAD1/5/8), which translocate to the nucleus to increase hepcidin transcription. Numerous other hepcidin regulators have been identified, many of which are proposed to intersect with the central BMP6/HJV/SMAD pathway at various levels as shown. Proposed iron-mediated hepcidin regulators are shown in yellow, inflammatory mediators in blue, iron deficiency mediators in purple, and anemia mediators in red. Abbreviations: TFR2, transferrin receptor 2; IL6, interleukin 6, sHJV, soluble hemojuvelin, TWSG1, twisted gastrulation 1, GDF15, growth and differentiation factor 15, TMPRSS6, transmembrane serine proteinase 6, EGF, epidermal growth factor, HGF, hepatocyte growth factor, mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

BMPs belong to the Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily of ligands (Shi and Massagué, 2003). In the canonical signaling pathway, BMP ligands bind to type I and type II serine threonine kinase receptors to induce phosphorylation of cytoplasmic SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8 proteins. These SMAD proteins form a complex with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene transcription. This signaling pathway is further regulated at multiple levels in order to generate a precise signal in a specific cellular context (Shi and Massagué, 2003).

HJV and other RGM family members function as BMP co-receptors that bind selectively to BMP ligands and receptors to enhance SMAD phosphorylation in response to BMP signals (Babitt et al., 2005, 2006; Samad et al., 2005). All RGMs share the ability to bind to the BMP2/BMP4 subfamily and enhance BMP2/BMP4 signaling (Babitt et al., 2005, 2006; Samad et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2012). Moreover, all RGMs utilize BMP type I receptors ALK2, ALK3, and ALK6, and allow preferential signaling through the BMP type II receptor ACTRIIA (Xia et al., 2007, 2008, 2010). However, HJV is unique from other RGMs in that it exhibits preferential ability to bind to the BMP5/BMP6/BMP7 subfamily compared with RGMA and RGMB (Wu et al., 2012).

The BMP-HJV-SMAD signaling pathway activates hepcidin transcription directly through specific BMP-responsive elements (BMP-REs) on the hepcidin promoter (Casanovas et al., 2009; Truksa et al., 2009a). A mutation in the proximal BMP-RE was associated with a more severe iron overload phenotype in a patient with classical HFE hemochromatosis, demonstrating its importance in hepcidin regulation in humans (Island et al., 2009). In mice, liver-specific disruption of Smad4, the BMP receptors type I Alk2 or Alk3, or the ligand Bmp6 result in hepcidin deficiency and iron overload, supporting the important role of these specific BMP-SMAD pathway components, in conjunction with HJV, in hepcidin regulation in vivo (Wang et al., 2005; Andriopoulos et al., 2009; Meynard et al., 2009; Steinbicker et al., 2011a).

Soluble HJV

In addition to the GPI-anchored membrane form of HJV, endogenous soluble HJV (sHJV) protein is detectable in human and rodent serum. (Lin et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2013). Multiple mechanisms have been proposed for endogenous sHJV generation, including cleavage by the pro-protein convertase furin and the type II transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS6 (Kuninger et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2008; Silvestri et al., 2008a,b). Whereas membrane HJV is a co-receptor for the BMP signaling complex (Babitt et al., 2006), sHJV can antagonize BMP signaling, presumably by binding and sequestering BMP ligands from interacting with cell-surface BMP type I and type II receptors (Babitt et al., 2007) (Figure 1). Indeed, the relative binding affinity of HJV for various BMP ligands roughly correlated with the ability of sHJV to inhibit their biological activity (Babitt et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2012).

Although exogenous sHJV inhibits BMP-SMAD signaling, the source, amount, and physiologic role(s) of endogenously produced sHJV in vivo are not well-understood. There is some evidence suggesting that endogenous sHJV is increased by iron deficiency and reduced by iron loading (Lin et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2007; Silvestri et al., 2008a; Brasse-Lagnel et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013). Interestingly, the furin cleaved form of sHJV appears to be more potent to inhibit BMP signaling and hepcidin compared with the TMPRSS6-cleaved form (Maxson et al., 2010). Whether HJV cleavage mainly represents a mechanism to remove the activating effects of liver membrane HJV, or whether endogenous sHJV has a direct BMP-SMAD inhibiting effect remains uncertain.

Extra-hepatic functions of HJV

In addition to the liver, HJV mRNA is also highly expressed in skeletal muscle and heart (Niederkofler et al., 2004; Papanikolaou et al., 2004), and has been detected in other tissues (Rodriguez Martinez et al., 2004, Rodriguez et al., 2007; Gnana-Prakasam et al., 2009; Luciani et al., 2011). Tissue specific differences in HJV mRNA regulation and HJV protein glycosylation patterns have also been described (Niederkofler et al., 2005; Fujikura et al., 2011). It was previously hypothesized that skeletal muscle and/or heart could serve as a source of sHJV to suppress hepcidin synthesis in response to iron deficiency or hypoxia (Lin et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). However, mice with a specific knockout of Hjv in skeletal ± cardiac muscle do not have altered hepcidin expression or systemic iron balance, at least under basal conditions or with dietary iron changes (Chen et al., 2011; Gkouvatsos et al., 2011). Whether strenuous exercise or hypoxia may uncover a role for muscle hemojuvelin remains uncertain. In contrast, hepatocyte specific Hjv knockout mice exhibit an iron overload phenotype similar to global Hjv knockout mice (Chen et al., 2011; Gkouvatsos et al., 2011). Thus, hepatic expression of HJV appears to have the most important physiologic role in systemic iron homeostasis regulation in vivo.

Iron stimulates BMP-SMAD signaling to regulate hepcidin

Iron regulates the activity of the BMP6-SMAD pathway to modulate hepcidin expression. Both circulating and liver iron appear to stimulate this pathway through different mechanisms (Ramos et al., 2011; Corradini et al., 2011a). In mice, liver iron content is positively correlated with liver Bmp6 mRNA levels and overall activity of the Smad signaling pathway (Kautz et al., 2008; Corradini et al., 2011a). Moreover, hepcidin induction by iron is inhibited by a neutralizing BMP6 antibody (Corradini et al., 2011a). These data suggest that liver iron modulates BMP6-SMAD signaling and hepcidin expression at least in part by regulating expression of BMP6 mRNA (Figure 1). It appears that liver iron regulates BMP6 expression mainly in nonparenchymal cells (Enns et al., 2013), and that iron loading in specific liver cell types may important for this regulation (Daba et al., 2013). However, the mechanism by which hepatic iron levels regulate BMP6 remains unknown. Notably, hepcidin is still increased to a lesser extent by chronic iron loading in Bmp6 and Hjv knockout mice, suggesting that these pathways do not completely account for hepcidin regulation by chronic iron loading (Ramos et al., 2011; Gkouvatsos et al., 2014).

Increases in circulating iron stimulate SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation and hepcidin expression without affecting Bmp6 mRNA levels (Corradini et al., 2011a). How circulating iron activates SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation is unknown, but may involve an interaction with other proteins that are mutated in adult-onset hereditary hemochromatosis (see section HFE and TFR2). HJV liver membrane protein expression itself does not appear to be regulated by iron (Krijt et al., 2012).

Iron administration and BMP6-SMAD signaling also up-regulate inhibitory SMAD7 and SMAD6, and TMPRSS6 (see section TMPRSS6), that can act as feedback inhibitors of BMP-SMAD signaling and hepcidin expression (Kautz et al., 2008; Mleczko-Sanecka et al., 2010; Meynard et al., 2011; Corradini et al., 2011a; Vujić Spasić et al., 2013). It has been hypothesized that these pathways may help prevent excessive hepcidin increases by iron to provide tight homeostatic control (Meynard et al., 2011; Corradini et al., 2011a).

Interaction of HJV and the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway with other hepcidin regulators

HFE and TFR2

Adult-onset hereditary hemochromatosis is a less severe iron-overload disorder that manifests later in life compared with JH, and is associated with mutations in HFE or TFR2 (encoding transferrin receptor 2) (Pietrangelo, 2010). Liver expression of HFE and TFR2 are clearly important for iron homeostasis regulation because mice with a hepatocyte-specific knockout of either gene have a similar iron-overload phenotype compared with global Hfe or Tfr2 knockout mice (Wallace et al., 2007; Vujić Spasić et al., 2008). Moreover, liver transplantation corrects much of the HFE hemochromatosis phenotype (Garuti et al., 2010; Bardou-Jacquet et al., 2014). Liver hepcidin expression is inappropriately low in mice and humans with HFE or TFR2 mutations, suggesting that both HFE and TFR2 positively regulate liver hepcidin expression (Ahmad et al., 2002; Fleming et al., 2002; Bridle et al., 2003; Muckenthaler et al., 2003; Kawabata et al., 2005; Nemeth et al., 2005; Piperno et al., 2007). HFE and TFR2 are also postulated to function in iron sensing by the liver. The current working model is that when iron-bound transferrin increases in circulation, it binds to transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) and displaces HFE, which then signals by some mechanism to stimulate hepcidin expression, possibly through an interaction with TFR2 (Schmidt et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2009).

It has been proposed that HFE and TFR2 may form a “supercomplex” with HJV to stimulate hepcidin expression via the BMP-SMAD pathway. Studies supporting this model have demonstrated that liver BMP-SMAD signaling is impaired in mice and humans with HFE and/or TFR2 mutations, suggesting an interaction at some level between HFE, TFR2 and the BMP-SMAD pathway (Corradini et al., 2009, 2011b; Kautz et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2009; Bolondi et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2010). Recently, it was published in an overexpression tissue culture system using tagged proteins that HFE and TFR2 can form a complex with HJV (D'Alessio et al., 2012). However, it is not been shown whether these proteins endogenously interact in vivo. Moreover, the more severe iron overload phenotype of HJV mutations and combined HFE/TFR2 mutations compared with either HFE or TFR2 mutations alone suggest that the function of these proteins is not entirely overlapping (Pietrangelo et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 2009). Thus, while it appears that HFE and TFR2 interact at some level with the BMP-HJV-SMAD pathway to regulate liver hepcidin expression (Figure 1), the precise molecular mechanisms of how HFE and TFR2 contribute to hepcidin regulation remain an active area of investigation.

The inflammatory pathway

In addition to iron, inflammatory stimuli also induce hepcidin expression (Ganz, 2013). The most well-characterized pathway is through IL6 activating the Janus kinase JAK2 to phosphorylate STAT3, which then activates the hepcidin promoter directly via a STAT3-binding motif (Wrighting and Andrews, 2006; Pietrangelo et al., 2007; Verga Falzacappa et al., 2007).

Although inflammation downregulates liver Hjv mRNA expression (Krijt et al., 2004; Niederkofler et al., 2005; Constante et al., 2007), liver SMAD1/5/8 signaling is often activated in the context of inflammation (Theurl et al., 2011) and is essential for hepcidin regulation by inflammation. Indeed, blocking BMP signaling with a small molecule BMP type I receptor inhibitor or a sHJV recombinant protein inhibits IL6-induced hepcidin expression in cell culture (Babitt et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008). Moreover, mice with a hepatocyte-specific knockout of Smad4 exhibit blunted hepcidin response to IL6 treatment (Wang et al., 2005). Importantly, BMP pathway inhibitors lower hepcidin, increase iron availability for erythropoiesis, and ameliorate anemia in animal models of anemia of inflammation (Theurl et al., 2011; Steinbicker et al., 2011b; Sun et al., 2013).

At least two mechanisms are proposed to account for the crosstalk between the BMP-SMAD and IL6-STAT3 pathways in hepcidin regulation. First, there may be an interaction at the level of the hepcidin promoter, where the proximal BMP-RE and the STAT3 binding site are in close proximity (Figure 1). In support of this hypothesis, mutation of the proximal BMP-RE impairs hepcidin promoter activation not only by BMPs, but also by IL6 (Casanovas et al., 2009). Second, inflammation induces hepatic expression of another TGF-β superfamily member, Activin B, which can stimulate hepcidin expression by activating SMAD1/5/8 signaling in hepatoma-derived cell cultures (Besson-Fournier et al., 2012) (Figure 1). Whether Activin B contributes to hepcidin regulation by inflammation in vivo remains to be determined.

TMPRSS6

The serine protease TMPRSS6 has been implicated in hepcidin inhibition by iron deficiency. Mutations in TMPRSS6 are linked to IRIDA associated with inappropriately high hepcidin levels (Du et al., 2008; Finberg et al., 2008; Folgueras et al., 2008). Moreover, genome-wide association studies have linked common single nucleotide polymorphisms in TMRPSS6 to iron status and hemoglobin level, supporting an important role for TMPRSS6 in regulating systemic iron homeostasis and normal erythropoiesis (Benyamin et al., 2009; Chambers et al., 2009; Tanaka et al., 2010). TMPRSS6 is proposed to regulate hepcidin expression through an interaction with HJV and the BMP-SMAD pathway in the liver. Specifically, when both proteins are overexpressed in cell culture, TMPRSS6 binds and cleaves HJV to generate sHJV, thereby inhibiting BMP-SMAD signaling (Silvestri et al., 2008b) (Figure 1). In mouse models, the combined deficiency of Hjv or Bmp6 and Tmprss6 causes iron overload, suggesting that there is a genetic interaction between TMPRSS6 and the BMP6-HJV-SMAD pathway (Truksa et al., 2009b; Finberg et al., 2010; Lenoir et al., 2011). Interestingly, liver membrane expression of Hjv is decreased (Krijt et al., 2011), and serum sHjv levels are unchanged (Chen et al., 2013), in Tmprss6 knockout mice compared with wildtype mice, which seem contrary to the proposed hypothesis that TMPRSS6 acts to cleave HJV from the liver membrane surface. Future work is needed to fully understand the mechanism of action of TMPRSS6 in hepcidin regulation and iron homeostasis in vivo.

Neogenin

In addition to TMPRSS6, the deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) family member neogenin is also proposed to function as an HJV interacting protein that modifies BMP-SMAD signaling and iron homeostasis (Figure 1). In particular, neogenin binds to HJV, like other RGM family members (Matsunaga et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005; Conrad et al., 2010). Moreover, neogenin mutant mice exhibit reduced hepcidin levels and iron overload consistent with a role for neogenin in regulating hepcidin and systemic iron balance in vivo (Lee et al., 2010). However, the mechanism of action of neogenin in hepcidin and iron homeostasis regulation is still not fully understood. In some studies, neogenin increased HJV cleavage (Enns et al., 2012), while in other studies, neogenin reduced HJV secretion (Lee et al., 2010). Moreover, neogenin was variably shown to inhibit (Hagihara et al., 2011), have no effect (Xia et al., 2008), or stimulate BMP signaling (Lee et al., 2010). Whether neogenin and HJV interact in a cell autonomous or cell non-autonomous manner in vivo remains unclear, and how this interaction occurs may be important for downstream functional effects.

Other pathways

Hepcidin suppression by erythropoietic drive appears to be mediated by secreted factor(s) released by proliferating red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow (Pak et al., 2006; Vokurka et al., 2006). Two proposed erythroid hepcidin regulators are the TGF-β /BMP superfamily modulators growth and differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) and twisted gastrulation 1 (TWSG1), at least in the context of ineffective erythropoiesis in iron loading anemias (Tanno et al., 2007, 2009) (Figure 1). The role of GDF15 and TWSG1 in hepcidin suppression by erythropoietic drive in other contexts has been questioned (Ashby et al., 2010; Casanovas et al., 2013). Recently, erythroferrone has been proposed as a novel erythroid regulator (Kautz et al., 2013), but its mechanism of action is not yet reported.

A number of other hormones, growth factors and signaling pathways have recently been implicated in hepcidin regulation including testosterone, estrogen, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), endoplasmic reticulum stress, gluconeogenic signals and the Ras/RAF and mTOR signaling pathways (Oliveira et al., 2009; Vecchi et al., 2009, 2014; Goodnough et al., 2012; Hou et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2013; Latour et al., 2014; Mleczko-Sanecka et al., 2014). Notably, the majority of these pathways appear to regulate hepcidin through an intersection with the BMP-SMAD pathway at some level (Goodnough et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2013; Latour et al., 2014; Mleczko-Sanecka et al., 2014) (Figure 1).

Conclusion

Understanding the genetic basis for JH has yielded important insights into the molecular mechanisms of systemic iron homeostasis. Hepcidin and its receptor ferroportin are key regulators of body iron balance, and the BMP-SMAD pathway via the co-receptor HJV is a central regulator of hepcidin production (Figure 1). Knowledge of these pathways has already lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies that target the molecular mechanisms underlying iron homeostasis disorders, with several new treatments currently being evaluated in human clinical trials (Fung and Nemeth, 2013). Future work will be needed to fully understand the mechanisms by which iron levels are sensed by the liver and integrated with other pathways to regulate BMP-SMAD signaling, hepcidin expression, and systemic iron homeostasis.

Conflict of interest statement

Jodie L. Babitt has ownership interest in a start-up company FerruMax Pharmaceuticals, which has licensed technology from the Massachusetts General Hospital based on the work cited here and in prior publications. All other authors declare the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Amanda B. Core was supported by NIH grant 5T32DK007540-28. Jodie L. Babitt was supported in part by NIH grant RO1-DK087727 and a Howard Goodman Fellowship Awards from the Massachusetts General Hospital.

References

- Aguilar-Martinez P., Lok C. Y., Cunat S., Cadet E., Robson K., Rochette J. (2007). Juvenile hemochromatosis caused by a novel combination of hemojuvelin G320V/R176C mutations in a 5-year old girl. Haematologica 92, 421–422 10.3324/haematol.10701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad K. A., Ahmann J. R., Migas M. C., Waheed A., Britton R. S., Bacon B. R., et al. (2002). Decreased liver hepcidin expression in the Hfe knockout mouse. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 29, 361–366 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriopoulos B., Jr., Corradini E., Xia Y., Faasse S. A., Chen S., Grgurevic L., et al. (2009). BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat. Genet. 41, 482–487 10.1038/ng.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby D. R., Gale D. P., Busbridge M., Murphy K. G., Duncan N. D., Cairns T. D., et al. (2010). Erythropoietin administration in humans causes a marked and prolonged reduction in circulating hepcidin. Haematologica 95, 505–508 10.3324/haematol.2009.013136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt J. L., Huang F. W., Wrighting D. M., Xia Y., Sidis Y., Samad T. A., et al. (2006). Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat. Genet. 38, 531–539 10.1038/ng1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt J. L., Huang F. W., Xia Y., Sidis Y., Andrews N. C., Lin H. Y. (2007). Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vivo regulates systemic iron balance. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1933–1939 10.1172/JCI31342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt J. L., Lin H. Y. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of hepcidin regulation: implications for the anemia of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 55, 726–741 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt J. L., Zhang Y., Samad T. A., Xia Y., Tang J., Campagna J. A., et al. (2005). Repulsive guidance molecule (RGMa), a DRAGON homologue, is a bone morphogenetic protein co-receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29820–29827 10.1074/jbc.M503511200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardou-Jacquet E., Philip J., Lorho R., Ropert M., Latournerie M., Houssel-Debry P., et al. (2014). Liver transplantation normalizes serum hepcidin level and cures iron metabolism alterations in HFE hemochromatosis. Hepatology 59, 839–847 10.1002/hep.26570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyamin B., Ferreira M. A., Willemsen G., Gordon S., Middelberg R. P., McEvoy B. P., et al. (2009). Common variants in TMPRSS6 are associated with iron status and erythrocyte volume. Nat. Genet. 41, 1173–1175 10.1038/ng.456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson-Fournier C., Latour C., Kautz L., Bertrand J., Ganz T., Roth M. P., et al. (2012). Induction of activin B by inflammatory stimuli up-regulates expression of the iron-regulatory peptide hepcidin through Smad1/5/8 signaling. Blood 120, 431–439 10.1182/blood-2012-02-411470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolondi G., Garuti C., Corradini E., Zoller H., Vogel W., Finkenstedt A., et al. (2010). Altered hepatic BMP signaling pathway in human HFE hemochromatosis. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 45, 308–312 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasse-Lagnel C., Poli M., Lesueur C., Grandchamp B., Lavoinne A., Beaumont C., et al. (2010). Immunoassay for human serum hemojuvelin. Haematologica 95, 2031–2037 10.3324/haematol.2010.022129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridle K. R., Frazer D. M., Wilkins S. J., Dixon J. L., Purdie D. M., Crawford D. H., et al. (2003). Disrupted hepcidin regulation in HFE-associated haemochromatosis and the liver as a regulator of body iron homoeostasis. Lancet 361, 669–673 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12602-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas G., Mleczko-Sanecka K., Altamura S., Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U. (2009). Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-responsive elements located in the proximal and distal hepcidin promoter are critical for its response to HJV/BMP/SMAD. J. Mol. Med. 87, 471–480 10.1007/s00109-009-0447-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas G., Spasic M. V., Casu C., Rivella S., Strelau J., Unsicker K., et al. (2013). The murine growth differentiation factor 15 is not essential for systemic iron homeostasis in phlebotomized mice. Haematologica 98, 444–447 10.3324/haematol.2012.069807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J. C., Zhang W., Li Y., Sehmi J., Wass M. N., Zabaneh D., et al. (2009). Genome-wide association study identifies variants in TMPRSS6 associated with hemoglobin levels. Nat. Genet. 41, 1170–1172 10.1038/ng.462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Huang F. W., de Renshaw T. B., Andrews N. C. (2011). Skeletal muscle hemojuvelin is dispensable for systemic iron homeostasis. Blood 117, 6319–6325 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Sun C. C., Chen S., Meynard D., Babitt J. L., Lin H. Y. (2013). A novel validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to quantify soluble hemojuvelin in mouse serum. Haematologica 98, 296–304 10.3324/haematol.2012.070136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad S., Stimpfle F., Montazeri S., Oldekamp J., Seid K., Alvarez-Bolado G., et al. (2010). RGMb controls aggregation and migration of Neogenin-positive cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 43, 222–231 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constante M., Wang D., Raymond V. A., Bilodeau M., Santos M. M. (2007). Repression of repulsive guidance molecule C during inflammation is independent of Hfe and involves tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 497–504 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradini E., Garuti C., Montosi G., Ventura P., Andriopoulos B., Jr., Lin H. Y., et al. (2009). Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is impaired in an HFE knockout mouse model of hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 137, 1489–1497 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradini E., Meynard D., Wu Q., Chen S., Ventura P., Pietrangelo A., et al. (2011a). Serum and liver iron differently regulate the bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6)-SMAD signaling pathway in mice. Hepatology 54, 273–284 10.1002/hep.24359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradini E., Rozier M., Meynard D., Odhiambo A., Lin H. Y., Feng Q., et al. (2011b). Iron regulation of hepcidin despite attenuated Smad1,5,8 signaling in mice without transferrin receptor 2 or Hfe. Gastroenterology 141, 1907–1914 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daba A., Gkouvatsos K., Sebastiani G., Pantopoulos K. (2013). Differences in activation of mouse hepcidin by dietary iron and parenterally administered iron dextran: compartmentalization is critical for iron sensing. J. Mol. Med. 91, 95–102 10.1007/s00109-012-0937-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessio F., Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U. (2012). The hemochromatosis proteins, HFE, TfR2, and HJV form a membrane-associated protein complex for hepcidin regulation. J. Hepatol. 57, 1052–1060 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gobbi M., Roetto A., Piperno A., Mariani R., Alberti F., Papanikolaou G., et al. (2002). Natural history of juvenile haemochromatosis. Br. J. Haematol. 117, 973–979 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Santos P. C., Pereira A. C., Cançado R. D., Schettert I. T., Hirata R. D., Hirata M. H., et al. (2010). Hemojuvelin and hepcidin genes sequencing in Brazilian patients with primary iron overload. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 14, 803–806 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., She E., Gelbart T., Truksa J., Lee P., Xia Y., et al. (2008). The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science 320, 1088–1092 10.1126/science.1157121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns C. A., Ahmed R., Wang J., Ueno A., Worthen C., Tsukamoto H., et al. (2013). Increased iron loading induces Bmp6 expression in the non-parenchymal cells of the liver independent of the BMP-signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 8:e60534 10.1371/journal.pone.0060534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns C. A., Ahmed R., Zhang A. S. (2012). Neogenin interacts with matriptase-2 to facilitate hemojuvelin cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 35104–35117 10.1074/jbc.M112.363937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg K. E., Heeney M. M., Campagna D. R., Aydinok Y., Pearson H. A., Hartman K. R., et al. (2008). Mutations in TMPRSS6 cause iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA). Nat. Genet. 40, 569–571 10.1038/ng.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg K. E., Whittlesey R. L., Fleming M. D., Andrews N. C. (2010). Down-regulation of Bmp/Smad signaling by Tmprss6 is required for maintenance of systemic iron homeostasis. Blood 115, 3817–3826 10.1182/blood-2009-05-224808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R. E., Ahmann J. R., Migas M. C., Waheed A., Koeffler H. P., Kawabata H., et al. (2002). Targeted mutagenesis of the murine transferrin receptor-2 gene produces hemochromatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 10653–10658 10.1073/pnas.162360699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgueras A. R., de Lara F. M., Pendás A. M., Garabaya C., Rodríguez F., Astudillo A., et al. (2008). Membrane-bound serine protease matriptase-2 (Tmprss6) is an essential regulator of iron homeostasis. Blood 112, 2539–2545 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura Y., Krijt J., Nečas E. (2011). Liver and muscle hemojuvelin are differently glycosylated. BMC Biochem. 12:52 10.1186/1471-2091-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung E., Nemeth E. (2013). Manipulation of the hepcidin pathway for therapeutic purposes. Haematologica 98, 1667–1676 10.3324/haematol.2013.084624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T. (2013). Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1721–1741 10.1152/physrev.00008.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Chen J., Kramer M., Tsukamoto H., Zhang A. S., Enns C. A. (2009). Interaction of the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE with transferrin receptor 2 is required for transferrin-induced hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 9, 217–227 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garuti C., Tian Y., Montosi G., Sabelli M., Corradini E., Graf R., et al. (2010). Hepcidin expression does not rescue the iron-poor phenotype of Kupffer cells in Hfe-null mice after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 139, 315–322 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke S. G., Pietrangelo A., Kascák M., Braner A., Eisold M., Kulaksiz H., et al. (2005). HJV gene mutations in European patients with juvenile hemochromatosis. Clin. Genet. 67, 425–428 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkouvatsos K., Fillebeen C., Daba A., Wagner J., Sebastiani G., Pantopoulos K. (2014). Iron-dependent regulation of hepcidin in Hjv-/- mice: evidence that hemojuvelin is dispensable for sensing body iron levels. PLoS ONE 9:e85530 10.1371/journal.pone.0085530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkouvatsos K., Wagner J., Papanikolaou G., Sebastiani G., Pantopoulos K. (2011). Conditional disruption of mouse HFE2 gene: maintenance of systemic iron homeostasis requires hepatic but not skeletal muscle hemojuvelin. Hepatology 54, 1800–1807 10.1002/hep.24547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnana-Prakasam J. P., Zhang M., Martin P. M., Atherton S. S., Smith S. B., Ganapathy V. (2009). Expression of the iron-regulatory protein haemojuvelin in retina and its regulation during cytomegalovirus infection. Biochem. J. 419, 533–543 10.1042/BJ20082240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnough J. B., Ramos E., Nemeth E., Ganz T. (2012). Inhibition of hepcidin transcription by growth factors. Hepatology 56, 291–299 10.1002/hep.25615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Bachman E., Li M., Roy C. N., Blusztajn J., Wong S., et al. (2013). Testosterone administration inhibits hepcidin transcription and is associated with increased iron incorporation into red blood cells. Aging Cell 12, 280–291 10.1111/acel.12052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara M., Endo M., Hata K., Higuchi C., Takaoka K., Yoshikawa H., et al. (2011). Neogenin, a receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 5157–5165 10.1074/jbc.M110.180919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Zhang S., Wang L., Li J., Qu G., He J., et al. (2012). Estrogen regulates iron homeostasis through governing hepatic hepcidin expression via an estrogen response element. Gene 511, 398–403 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F. W., Pinkus J. L., Pinkus G. S., Fleming M. D., Andrews N. C. (2005). A mouse model of juvenile hemochromatosis. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2187–2191 10.1172/JCI25049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F. W., Rubio-Aliaga I., Kushner J. P., Andrews N. C., Fleming M. D. (2004). Identification of a novel mutation (C321X) in HJV. Blood 104, 2176–2177 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Island M. L., Jouanolle A. M., Mosser A., Deugnier Y., David V., Brissot P., et al. (2009). A new mutation in the hepcidin promoter impairs its BMP response and contributes to a severe phenotype in HFE related hemochromatosis. Haematologica 94, 720–724 10.3324/haematol.2008.001784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jánosi A., Andrikovics H., Vas K., Bors A., Hubay M., Sápi Z., et al. (2005). Homozygosity for a novel nonsense mutation (G66X) of the HJV gene causes severe juvenile hemochromatosis with fatal cardiomyopathy. Blood 105, 432 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka C., Le Gac G., Letocart E., Gourlaouen I., Martin B., Férec C. (2007). Phenotypic and functional data confirm causality of the recently identified hemojuvelin pr176c missense mutation. Haematologica 9, 1262–1263 10.3324/haematol.11247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz L., Jung G., Nemeth E., Ganz T. (2013). The erythroid factor erythroferrone and its role in iron homeostasis [Abstract]. Blood 122:4 Available online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/content/122/21/4.abstract23828884 [Google Scholar]

- Kautz L., Meynard D., Besson-Fournier C., Darnaud V., Al Saati T., Coppin H., et al. (2009). BMP/Smad signaling is not enhanced in Hfe-deficient mice despite increased Bmp6 expression. Blood 114, 2515–2520 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz L., Meynard D., Monnier A., Darnaud V., Bouvet R., Wang R. H., et al. (2008). Iron regulates phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and gene expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 in the mouse liver. Blood 112, 1503–1509 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata H., Fleming R. E., Gui D., Moon S. Y., Saitoh T., O'Kelly J., et al. (2005). Expression of hepcidin is down-regulated in TfR2 mutant mice manifesting a phenotype of hereditary hemochromatosis. Blood 105, 376–381 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijt J., Frýdlová J., Kukačková L., Fujikura Y., Přikryl P., Vokurka M., et al. (2012). Effect of iron overload and iron deficiency on liver hemojuvelin protein. PLoS ONE 7:e37391 10.1371/journal.pone.0037391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijt J., Fujikura Y., Ramsay A. J., Velasco G., Nečas E. (2011). Liver hemojuvelin protein levels in mice deficient in matriptase-2 (Tmprss6). Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 47, 133–137 10.1016/j.bcmd.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijt J., Vokurka M., Chang K. T., Necas E. (2004). Expression of Rgmc, the murine ortholog of hemojuvelin gene, is modulated by development and inflammation, but not by iron status or erythropoietin. Blood 104, 4308–4310 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuninger D., Kuns-Hashimoto R., Nili M., Rotwein P. (2008). Pro-protein convertases control the maturation and processing of the iron-regulatory protein, RGMc/hemojuvelin. BMC Biochem. 9:9 10.1186/1471-break2091-9-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzara C., Roetto A., Daraio F., Rivard S., Ficarella R., Simard H., et al. (2004). Spectrum of hemojuvelin gene mutations in 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Blood 103, 4317–4321 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour C., Kautz L., Besson-Fournier C., Island M. L., Canonne-Hergaux F., Loréal O., et al. (2014). Testosterone perturbs systemic iron balance through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in the liver and repression of hepcidin. Hepatology 59, 683–694 10.1002/hep.26648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. H., Zhou L. J., Zhou Z., Xie J. X., Jung J. U., Liu Y., et al. (2010). Neogenin inhibits HJV secretion and regulates BMP-induced hepcidin expression and iron homeostasis. Blood 115, 3136–3145 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. L., Beutler E., Rao S. V., Barton J. C. (2004). Genetic abnormalities and juvenile hemochromatosis: mutations of the HJV gene encoding hemojuvelin. Blood 103, 4669–4671 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gac G., Scotet V., Ka C., Gourlaouen I., Bryckaert L., Jacolot S., et al. (2004). The recently identified type 2A juvenile haemochromatosis gene (HJV), a second candidate modifier of the C282Y homozygous phenotype. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 1913–1918 10.1093/hmg/ddh206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir A., Deschemin J. C., Kautz L., Ramsay A. J., Roth M. P., Lopez-Otin C., et al. (2011). Iron-deficiency anemia from matriptase-2 inactivation is dependent on the presence of functional Bmp6. Blood 117, 647–650 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Goldberg Y. P., Ganz T. (2005). Competitive regulation of hepcidin mRNA by soluble and cell-associated hemojuvelin. Blood 106, 2884–2889 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Nemeth E., Goodnough J. B., Thapa D. R., Gabayan V., Ganz T. (2008). Soluble hemojuvelin is released by proprotein convertase-mediated cleavage at a conserved polybasic RNRR site. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 40, 122–131 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciani N., Brasse-Lagnel C., Poli M., Anty R., Lesueur C., Cormont M., et al. (2011). Hemojuvelin: a new link between obesity and iron homeostasis. Obesity (Silver. Spring). 19, 1545–1551 10.1038/oby.2011.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga E., Tauszig-Delamasure S., Monnier P. P., Mueller B. K., Strittmatter S. M., Mehlen P., et al. (2004). RGM and its receptor neogenin regulate neuronal survival. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 749–755 10.1038/ncb1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxson J. E., Chen J., Enns C. A., Zhang A. S. (2010). Matriptase-2- and proprotein convertase-cleaved forms of hemojuvelin have different roles in the down-regulation of hepcidin expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39021–39028 10.1074/jbc.M110.183160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meynard D., Kautz L., Darnaud V., Canonne-Hergaux F., Coppin H., Roth M. P. (2009). Lack of the bone morphogenetic protein BMP6 induces massive iron overload. Nat. Genet. 41, 478–481 10.1038/ng.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meynard D., Vaja V., Sun C. C., Corradini E., Chen S., López-Otín C., et al. (2011). Regulation of TMPRSS6 by BMP6 and iron in human cells and mice. Blood 118, 747–756 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mleczko-Sanecka K., Casanovas G., Ragab A., Breitkopf K., Müller A., Boutros M., et al. (2010). SMAD7 controls iron metabolism as a potent inhibitor of hepcidin expression. Blood 115, 2657–2665 10.1182/blood-2009-09-238105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mleczko-Sanecka K., Roche F., da Silva A. R., Call D., D'Alessio F., Ragab A., et al. (2014). Unbiased RNAi screen for hepcidin regulators links hepcidin suppression to the proliferative Ras/RAF and the nutrient-dependent mTOR signaling pathways. Blood 123, 1574–1585 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier P. P., Sierra A., Macchi P., Deitinghoff L., Andersen J. S., Mann M., et al. (2002). RGM is a repulsive guidance molecule for retinal axons. Nature 419, 392–395 10.1038/nature01041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckenthaler M., Roy C. N., Custodio A. O., Miñana B., deGraaf J., Montross L. K., et al. (2003). Regulatory defects in liver and intestine implicate abnormal hepcidin and Cybrd1 expression in mouse hemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 34, 102–107 10.1038/ng1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan R. C., Lee P. L., Kalavar M. R., Barton J. C. (2008). Early age-of-onset iron overload and homozygosity for the novel hemojuvelin mutation HJV R54X (exon 3; c160A–>T) in an African American male of West Indies descent. Clin. Genet. 74, 88–92 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayoshi Y., Nakayama M., Suzuki S., Hokamaki J., Shimomura H., Tsujita K., et al. (2008). A Q312X mutation in the hemojuvelin gene is associated with cardiomyopathy due to juvenile haemochromatosis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10, 1001–1006 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth E., Roetto A., Garozzo G., Ganz T., Camaschella C. (2005). Hepcidin is decreased in TFR2 hemochromatosis. Blood 105, 1803–1806 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkofler V., Salie R., Arber S. (2005). Hemojuvelin is essential for dietary iron sensing, and its mutation leads to severe iron overload. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2180–2186 10.1172/JCI25683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkofler V., Salie R., Sigrist M., Arber S. (2004). Repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) gene function is required for neural tube closure but not retinal topography in the mouse visual system. J. Neurosci. 24, 808–818 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4610-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira S. J., Pinto J. P., Picarote G., Costa V. M., Carvalho F., Rangel M., et al. (2009). ER stress-inducible factor CHOP affects the expression of hepcidin by modulating C/EBPalpha activity. PLoS ONE 4:e6618 10.1371/journal.pone.0006618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak M., Lopez M. A., Gabayan V., Ganz T., Rivera S. (2006). Suppression of hepcidin during anemia requires erythropoietic activity. Blood 108, 3730–3735 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou G., Samuels M. E., Ludwig E. H., MacDonald M. L., Franchini P. L., Dubé MP., et al. (2004). Mutations in HFE2 cause iron overload in chromosome 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 36, 77–82 10.1038/ng1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrangelo A. (2010). Hereditary hemochromatosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 139, 393–408 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrangelo A., Caleffi A., Henrion J., Ferrara F., Corradini E., Kulaksiz H., et al. (2005). Juvenile hemochromatosis associated with pathogenic mutations of adult hemochromatosis genes. Gastroenterology 128, 470–479 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrangelo A., Dierssen U., Valli L., Garuti C., Rump A., Corradini E., et al. (2007). STAT3 is required for IL-6-gp130-dependent activation of hepcidin in vivo. Gastroenterology 132, 294–300 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno A., Girelli D., Nemeth E., Trombini P., Bozzini C., Poggiali E., et al. (2007). Blunted hepcidin response to oral iron challenge in HFE-related hemochromatosis. Blood 110, 4096–4100 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos E., Kautz L., Rodriguez R., Hansen M., Gabayan V., Ginzburg Y., et al. (2011). Evidence for distinct pathways of hepcidin regulation by acute and chronic iron loading in mice. Hepatology 53, 1333–1341 10.1002/hep.24178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A., Pan P., Parkkila S. (2007). Expression studies of neogenin and its ligand hemojuvelin in mouse tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55, 85–96 10.1369/jhc.6A7031.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Martinez A., Niemelä O., Parkkila S. (2004). Hepatic and extrahepatic expression of the new iron regulatory protein hemojuvelin. Haematologica 89, 1441–1445 Available online at: http://www.haematologica.org/content/89/12/1441.long [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roetto A., Papanikolaou G., Politou M., Alberti F., Girelli D., Christakis J., et al. (2003). Mutant antimicrobial peptide hepcidin is associated with severe juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 33, 21–22 10.1038/ng1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J. D., Ryan E., Fabre A., Lawless M. W., Crowe J. (2010). Defective bone morphogenic protein signaling underlies hepcidin deficiency in HFE hereditary hemochromatosis. Hepatology 52, 1266–1273 10.1002/hep.23814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad T. A., Rebbapragada A., Bell E., Zhang Y., Sidis Y., Jeong S. J., et al. (2005). DRAGON, a bone morphogenetic protein co-receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14122–14129 10.1074/jbc.M410034200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad T. A., Srinivasan A., Karchewski L. A., Jeong S. J., Campagna J. A., Ji R. R., et al. (2004). DRAGON: a member of the repulsive guidance molecule-related family of neuronal- and muscle-expressed membrane proteins is regulated by DRG11 and has neuronal adhesive properties. J. Neurosci. 24, 2027–2036 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4115-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P. C., Cançado R. D., Pereira A. C., Schettert I. T., Soares R. A., Pagliusi R. A., et al. (2011). Hereditary hemochromatosis: mutations in genes involved in iron homeostasis in Brazilian patients. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 46, 302–307 10.1016/j.bcmd.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P. C., Krieger J. E., Pereira A. C. (2012). Molecular diagnostic and pathogenesis of hereditary hemochromatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 1497–1511 10.3390/ijms13021497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt P. J., Toran P. T., Giannetti A. M., Bjorkman P. J., Andrews N. C. (2008). The transferrin receptor modulates Hfe-dependent regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 7, 205–214 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Massagué J. (2003). Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113, 685–700 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00432-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri L., Pagani A., Camaschella C. (2008a). Furin-mediated release of soluble hemojuvelin: a new link between hypoxia and iron homeostasis. Blood 111, 924–931 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri L., Pagani A., Fazi C., Gerardi G., Levi S., Arosio P., et al. (2007). Defective targeting of hemojuvelin to plasma membrane is a common pathogenetic mechanism in juvenile hemochromatosis. Blood 109, 4503–4510 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri L., Pagani A., Nai A., De Domenico I., Kaplan J., Camaschella C. (2008b). The serine protease matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) inhibits hepcidin activation by cleaving membrane hemojuvelin. Cell Metab. 8, 502–511 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbicker A. U., Bartnikas T. B., Lohmeyer L. K., Leyton P., Mayeur C., Kao S. M., et al. (2011a). Perturbation of hepcidin expression by BMP type I receptor deletion induces iron overload in mice. Blood 118, 4224–4230 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbicker A. U., Sachidanandan C., Vonner A. J., Yusuf R. Z., Deng D. Y., Lai C. S., et al. (2011b). Inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein signaling attenuates anemia associated with inflammation. Blood 117, 4915–4923 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C. C., Vaja V., Chen S., Theurl I., Stepanek A., Brown D. E., et al. (2013). A hepcidin lowering agent mobilizes iron for incorporation into red blood cells in an adenine-induced kidney disease model of anemia in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 28, 1733–1743 10.1093/ndt/gfs584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Roy C. N., Yao W., Matteini A., Semba R. D., Arking D., et al. (2010). A genome-wide association analysis of serum iron concentrations. Blood 115, 94–96 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno T., Bhanu N. V., Oneal P. A., Goh S. H., Staker P., Lee Y. T., et al. (2007). High levels of GDF15 in thalassemia suppress expression of the iron regulatory protein hepcidin. Nat. Med. 13, 1096–1101 10.1038/nm1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno T., Porayette P., Sripichai O., Noh S. J., Byrnes C., Bhupatiraju A., et al. (2009). Identification of TWSG1 as a second novel erythroid regulator of hepcidin expression in murine and human cells. Blood 114, 181–186 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurl I., Schroll A., Sonnweber T., Nairz M., Theurl M., Willenbacher W., et al. (2011). Pharmacologic inhibition of hepcidin expression reverses anemia of chronic inflammation in rats. Blood 118, 4977–4984 10.1182/blood-2011-03-345066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truksa J., Gelbart T., Peng H., Beutler E., Beutler B., Lee P. (2009b). Suppression of the hepcidin-encoding gene Hamp permits iron overload in mice lacking both hemojuvelin and matriptase-2/TMPRSS6. Br. J. Haematol. 147, 571–581 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07873.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truksa J., Lee P., Beutler E. (2009a). Two BMP responsive elements, STAT, and bZIP/HNF4/COUP motifs of the hepcidin promoter are critical for BMP, SMAD1, and HJV responsiveness. Blood 113, 688–695 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk B. A., Kemna E. H., Tjalsma H., Klaver S. M., Wiegerinck E. T., Goossens J. P., et al. (2007). Effect of the new HJV-L165X mutation on penetrance of HFE. Blood 109, 5525–5526 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi C., Montosi G., Garuti C., Corradini E., Sabelli M., Canali S., et al. (2014). Gluconeogenic signals regulate iron homeostasis via hepcidin in mice. Gastroenterology 146, 1060–1069 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi C., Montosi G., Zhang K., Lamberti I., Duncan S. A., Kaufman R. J., et al. (2009). ER stress controls iron metabolism through induction of hepcidin. Science 325, 877–880 10.1126/science.1176639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verga Falzacappa M. V., Vujic Spasic M., Kessler R., Stolte J., Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U. (2007). STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood 109, 353–358 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokurka M., Krijt J., Sulc K., Necas E. (2006). Hepcidin mRNA levels in mouse liver respond to inhibition of erythropoiesis. Physiol. Res. 55, 667–674 Available onlne at: http://www.biomed.cas.cz/physiolres/pdf/55/55_667.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujić Spasić M., Kiss J., Herrmann T., Galy B., Martinache S., Stolte J., et al. (2008). Hfe acts in hepatocytes to prevent hemochromatosis. Cell Metab. 7, 173–178 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujić Spasić M., Sparla R., Mleczko-Sanecka K., Migas M. C., Breitkopf-Heinlein K., Dooley S., et al. (2013). Smad6 and Smad7 are co-regulated with hepcidin in mouse models of iron overload. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1832, 76–84 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. F., Summerville L., Crampton E. M., Frazer D. M., Anderson G. J., Subramaniam V. N. (2009). Combined deletion of Hfe and transferrin receptor 2 in mice leads to marked dysregulation of hepcidin and iron overload. Hepatology 50, 1992–2000 10.1002/hep.23198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. F., Summerville L., Subramaniam V. N. (2007). Targeted disruption of the hepatic transferrin receptor 2 gene in mice leads to iron overload. Gastroenterology 132, 301–310 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. H., Li C., Xu X., Zheng Y., Xiao C., Zerfas P., et al. (2005). A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2, 399–409 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrighting D. M., Andrews N. C. (2006). Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood 108, 3204–3209 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Sun C. C., Lin H. Y., Babitt J. L. (2012). Repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) family proteins exhibit differential binding kinetics for bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). PLoS ONE 7:e46307 10.1371/journal.pone.0046307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Babitt J. L., Bouley R., Zhang Y., Da Silva N., Chen S., et al. (2010). Dragon enhances BMP signaling and increases transepithelial resistance in kidney epithelial cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 666–677 10.1681/ASN.2009050511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Babitt J. L., Sidis Y., Chung R. T., Lin H. Y. (2008). Hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression via a selective subset of BMP ligands and receptors independently of neogenin. Blood 111, 5195–5204 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Yu P. B., Sidis Y., Beppu H., Bloch K. D., Schneyer A. L., et al. (2007). Repulsive guidance molecule RGMa alters utilization of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptors by BMP2 and BMP4. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18129–18140 10.1074/jbc.M701679200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Jian J., Katz S., Abramson S. B., Huang X. (2012). 17β-Estradiol inhibits iron hormone hepcidin through an estrogen responsive element half-site. Endocrinology 153, 3170–3178 10.1210/en.2011-2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P. B., Hong C. C., Sachidanandan C., Babitt J. L., Deng D. Y., Hoyng S. A., et al. (2008). Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 33–41 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A. S., Anderson S. A., Meyers K. R., Hernandez C., Eisenstein R. S., Enns C. A. (2007). Evidence that inhibition of hemojuvelin shedding in response to iron is mediated through neogenin. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12547–12556 10.1074/jbc.M608788200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A. S., West A. P., Jr., Wyman A. E., Bjorkman P. J., Enns C. A. (2005). Interaction of hemojuvelin with neogenin results in iron accumulation in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33885–33894 10.1074/jbc.M506207200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]