Abstract

Background. The aim of this report was to evaluate the clinical profile and previous management of patients with uncontrolled neuropathic pain who were referred to pain clinics. Methods. We included adult patients with uncontrolled pain who had a score of ≥4 in the DN4 questionnaire. In addition to sociodemographic and clinical data, we evaluated pain levels using a visual analog scale as well as anxiety, depression, sleep, disability, and treatment satisfaction employing validated tools. Results. A total of 755 patients were included in the study. The patients were predominantly referred to pain clinics by traumatologists (34.3%) and primary care physicians (16.7%). The most common diagnoses were radiculopathy (43%) and pain of oncological origin (14.3%). The major cause for uncontrolled pain was suboptimal treatment (88%). Fifty-three percent of the patients were depressed, 43% had clinical anxiety, 50% rated their overall health as bad or very bad, and 45% noted that their disease was severely or extremely interfering with their daily activities. Conclusions. Our results showed that uncontrolled neuropathic pain is a common phenomenon among the specialties that address these clinical entities and, regardless of its etiology, uncontrolled pain is associated with a dramatic impact on patient well-being.

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is defined as pain that originates from a lesion or disease that affects the somatosensory pathways within the peripheral or central nervous system [1]. Neuropathic pain is common among the general population, with prevalence rates of 7-8% [2, 3]. Neuropathic pain, which is also a common occurrence (12%) among patients who are managed by primary care physicians [4], accounts for a high proportion (20%) of the patients who are referred to specialized pain units [5]. The causes of neuropathic pain comprise a wide and heterogeneous number of clinical conditions, such as diabetic neuropathy, complex regional pain syndrome, spinal cord injury pain, postherpetic neuralgia, postoperative pain, trigeminal neuralgia, drug-induced polyneuropathies, HIV-associated neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, and central pain syndromes secondary to vascular lesions [6, 7]. Although it may be acute in nature, in the vast majority of patients, neuropathic pain is a chronic condition. Regardless of its etiology, neuropathic pain is disabling and substantially impairs patients' health-related quality of life [8–12]. This condition is associated with high societal costs because of the patients' loss of productivity and increased utilization of health resources [8, 10, 13–15].

Managing neuropathic pain requires an interdisciplinary approach in which pharmacological treatment is fundamental [5, 16]. Despite the availability of several effective drugs, neuropathic pain treatment is challenging: response to treatment is unpredictable; despite the fact that the patients may receive several drugs for pain treatment, moderate-to-severe levels of pain are common; suboptimal treatment is also common with patients who receive ineffective treatments, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or lower-than-recommended doses of the prescribed treatment; and delayed referral to pain clinics is also common [4, 8, 16–18].

Although there is consensus that many patients with neuropathic pain do not respond adequately or are unable to tolerate existing treatments [19, 20], epidemiologic information about this population is limited [21]. The aim of this report was to evaluate the clinical profile and previous management of patients with uncontrolled neuropathic pain who were referred to pain clinics.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Patients

This report was an observational, multicenter, and prospective study performed by 161 investigators from pain clinics throughout Spain between February 2009 and February 2010. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (Spain). Written informed consent was obtained from every subject. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In this report, we presented the baseline (cross-sectional) data of the study.

For inclusion in the study, the patients had to fulfill the following criteria: age 18 years or older; referral to a pain clinic because of uncontrolled pain; and a score of equal to or greater than 4 in the DN4 questionnaire. The patients were excluded from the study if they were unable to understand the study objectives or complete the self-administered questionnaires.

2.2. Study Assessments

At baseline, the following information was recorded: sociodemographic data, type of specialist referring the patient, diagnostic confirmation of neuropathic pain, confirmation of the presence of uncontrolled pain as assessed by the investigator, etiology and duration of pain, causes for uncontrolled pain, pain intensity as measured using a 0 to 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS), and signs and symptoms of neuropathic pain. We also recorded pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment for neuropathic pain. Additionally, the Spanish validated versions of the following questionnaires and scales were completed: DN4 questionnaire, Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep (MOS Sleep) Scale, the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS II), and the Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire (SATMED-Q).

The neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire DN4 consists of 10 items that describe different pain characteristics. A score of at least 4 of 10 possible points is considered acceptable to identify neuropathic pain with 83% sensitivity and 90% specificity [22–24].

The HADS, which is a self-administered instrument, consists of 14 items: 7 items that refer to depression symptoms and 7 items that refer to anxiety symptoms [25, 26]. Each item score ranges from 0 to 3, where 0 represents the absence of that symptom and 3 represents the highest severity or frequency of the symptom. By adding the 7 items of each subscale, two scores ranging from 0 to 21 are obtained that represent depression and anxiety (HADS-D and HADS-A), respectively.

The MOS Sleep Scale, a self-administered questionnaire, evaluates the key aspects of sleep [27, 28] and consists of 12 items that comprise six subscales or domains: sleep disturbances, snoring, shortness of breath or headache upon awakening, adequacy of sleep, day somnolence, and amount of sleep. Additionally, the MOS Sleep Scale provides a summary index of sleep disturbances that can be obtained from 9 of its items; the higher the score is, the worse the sleep is, with the exception of amount of sleep and adequacy of sleep dimensions, which are scored in the opposite direction. In patients with neuropathic pain, this scale has shown to have appropriate psychometric properties [28].

The WHO-DAS II comprises 12 items that evaluate an individual's level of functioning and disability in six areas: understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with people, life activities, and participation in society [29–31]. The patients are required to answer questions regarding how many difficulties they experienced in the last 30 days as a result of their health condition, using a five-point scale from 1 (none) to 5 (extreme difficulty or cannot do it). The raw scores are transformed into a standard scale that ranges from 0 to 100; the higher scores reflect more severe disability. A global score is obtained that ranges from 0 to 700 (if work activities outside the home are assessed) or from 0 to 600.

The SATMED-Q, a self-administered questionnaire, consists of 17 items that evaluate six dimensions: treatment effectiveness, convenience of use, impact on daily activities, medical care, global satisfaction, and undesirable side-effects [32, 33]. The questionnaire also provides a global score for satisfaction with drug treatment by summing the scores of all of the domains. The raw scores are transformed into a scale that ranges from 0 to 100; the higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. Questions on medication side-effects include whether the patient experienced side-effects and whether the side-effects interfered with their physical exercises, leisure time, and daily activities.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis was essentially descriptive using the means and standard deviations for quantitative variables and using the absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables. The patients were categorized as having clinical anxiety or depression if they had a score equal or greater than 11 in the anxiety or depression subscales of the HAD.

3. Results

We included 755 patients in the study. We excluded 27 (3.6%) patients who did not meet the selection criteria, thereby leaving 728 evaluable patients.

3.1. General Characteristics of Patients

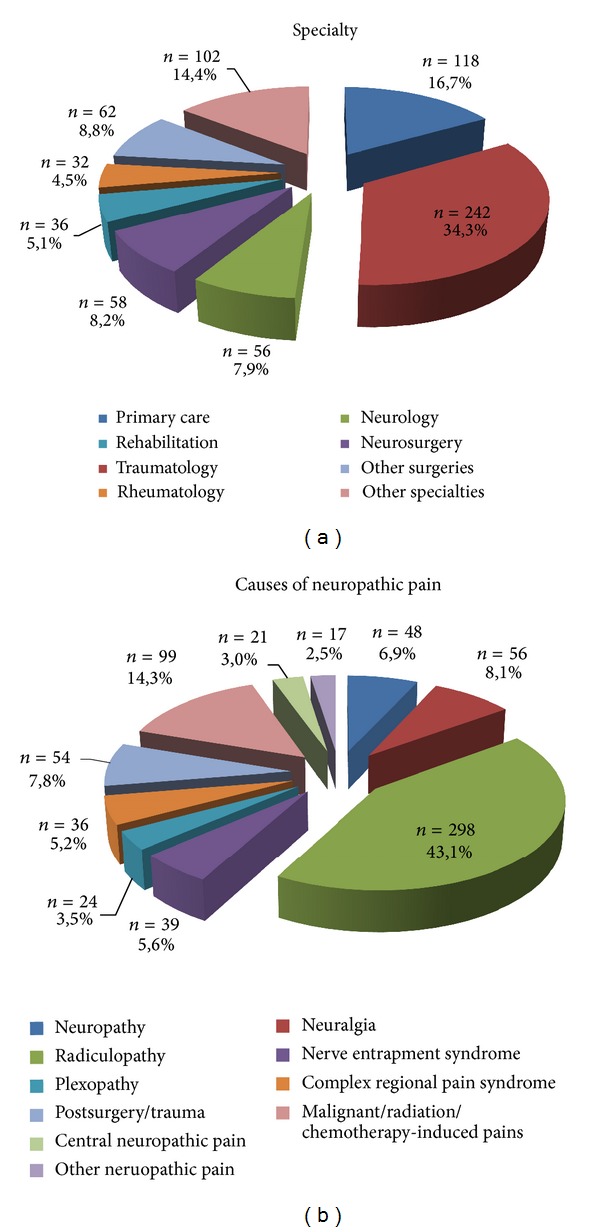

The patients had a mean age of 57 years, were predominantly women (61%), and exhibited obesity in a high proportion (20%) (Table 1). More than one-third of the patients were referred to pain clinics by traumatologists, followed by those who were referred by primary care physicians (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics for the overall simple and referring specialty.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 | Primary care N = 118 | Traumatology N = 242 | Neurology N = 56 | Neurosurgery N = 58 | Rehabilitation N = 36 | Rheumatology N = 32 | Other surgeries N = 62 | Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 57.2 ± 15.2 | 63.3 ± 13.6 | 56.2 ± 14.2 | 54.9 ± 14.9 | 54.3 ± 12.0 | 53.0 ± 14.8 | 55.5 ±13.1 | 57.3 ± 13.7 | 61.5 ± 13.5 |

| Sex (female), % | 60.6 | 56.3 | 65.8 | 60.7 | 63.0 | 51.4 | 78.1 | 59.7 | 51.0 |

| BMI, % | |||||||||

| Underweight | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 34.4 | 31.8 | 31.2 | 36.2 | 36.4 | 39.4 | 27.6 | 43.1 | 40.2 |

| Overweight Obesity I | 43.9 | 51.4 | 43.7 | 38.3 | 47.7 | 36.4 | 41.4 | 37.3 | 45.1 |

| Obesity II | 16.7 | 15.0 | 19.6 | 12.8 | 11.4 | 18.2 | 17.2 | 17.6 | 11.0 |

| Obesity III | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Obesity IV | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Specialists referring patients and clinical entities referred to pain clinics.

3.2. Pain Characteristics and Treatment

The patients had severe pain with a mean score of 75 using the VAS; the duration of pain was generally 2,6 years and was longer for those patients who were referred to pain clinics from the departments of rheumatology, neurosurgery, and neurology (Table 2). The majority (43%) of the patients were diagnosed with radiculopathy (Figure 1), which was the predominant diagnosis among those patients referred by traumatology, neurosurgery, rheumatology, and rehabilitation departments (Table 2). The patients who were referred by neurologists had trigeminal neuralgia and central neuropathic pain as their primary diagnoses, whereas primary care physicians referred patients with oncological pain or radiculopathy. The type, spontaneous or evoked, and subtypes of pain by clinical entity are presented in Table 3. All subtypes of spontaneous pain were present in more than 80% of the patients, regardless of the clinical entity. The subtypes of evoked pain were less represented, especially thermal allodynia; however, nearly every subtype was present in more than two-thirds of the patients in every clinical entity.

Table 2.

Pain characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 | Primary care N = 118 | Traumatology N = 242 | Neurology N = 56 | Neurosurgery N = 58 | Rehabilitation N = 36 | Rheumatology N = 32 | Other surgeries N = 62 | Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DN4 (0–10), mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 1.6 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 7.1 ± 1.8 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.6 |

| VAS, mean ± SD | 74.5 ± 15.3 | 73.7 ± 15.5 | 76.6 ± 13.5 | 75.8 ± 15.8 | 73.9 ± 15.1 | 76.0 ± 12.2 | 70.9 ± 12.6 | 72.3 ± 18.6 | 73.0 ± 17.3 |

| Duration of pain (yrs), mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 3.6 | 2.2 ± 3.1 | 2.5 ± 3.5 | 3.7 ± 4.4 | 4.3 ± 5.3 | 3.3 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 5.6 | 1.2 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 2.3 |

| Causes for uncontrolled pain, % | |||||||||

| Misdiagnosis | 11.1 | 11.9 | 12.8 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 12.7 | 9.4 | 16.1 | 8.3 |

| Nonoptimized treatment | 87.6 | 82.2 | 93.4 | 82.1 | 87.9 | 83.3 | 90.6 | 88.7 | 83.3 |

| Use of ineffective drugs | 45.8 | 45.9 | 50.4 | 28.3 | 37.3 | 46.7 | 41.4 | 52.7 | 44.3 |

| Subtherapeutic dose | 45.7 | 48.5 | 46.0 | 47.8 | 43.1 | 56.5 | 41.4 | 30.9 | 50.0 |

| Other | 25.3 | 18.6 | 23.5 | 37.0 | 39.2 | 20.0 | 24.7 | 21.8 | 31.0 |

| Lack of compliance | 7.2 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 12.5 | 5.2 | 11.1 | 15.6 | 4.8 | 6.2 |

| Intolerance | 6.6 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 16.1 | 6.9 | 2.8 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 7.8 |

| Other | 7.3 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 6.9 | 11.1 | 3.1 | 8.1 | 4.1 |

| Causes of neuropathic pain, % | |||||||||

| Neuropathy | |||||||||

| Diabetic | 3.8 | 10.4 | 0.9 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 6.1 |

| Other | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 0.0 |

| Neuralgia | |||||||||

| Trigeminal | 4.6 | 7.0 | 0.4 | 25.0 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Other | 3.5 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 8.8 |

| Radiculopathy | 43.1 | 32.5 | 67.0 | 11.5 | 63.6 | 52.8 | 63.3 | 8.3 | 3.5 |

| Nerve entrapment syndrome | 5.6 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 16.7 | 1.8 | 9.4 |

| Plexopathy | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 5.2 | 0.9 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 16.7 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| Postsurgery/trauma | 7.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 11.5 | 45.6 |

| Malignant/radiation/chemotherapy-induced pain | 14.3 | 36.0 | 1.3 | 11.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 41.7 | 8.8 |

| Central neuropathic pain | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 17.3 | 5.5 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Other neuropathic pains | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 10.5 | 2.8 |

DN4: neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire; SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analog scale; Yrs: years.

Table 3.

Type of pain by clinical entity.

| Characteristic | Diabetic neuropathy N = 26 | Other neuropathies N = 22 | Trigeminal neuralgia N = 32 | Other neuralgia N = 24 | Radiculopathy N = 298 | Nerve entrapment syndrome N = 39 | Plexopathy N = 24 | Complex regional pain syndrome N = 36 | Postsurgery/trauma N = 54 | Oncological pain N = 99 | Central neuropathic pain N = 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous pain, % | |||||||||||

| Lancinating | 98.0 | 89.5 | 96.6 | 100.0 | 60.1 | 91.2 | 81.0 | 87.5 | 90.9 | 90.4 | 90.0 |

| Burning | 100.0 | 90.0 | 95.7 | 92.6 | 87.0 | 97.1 | 82.7 | 96.9 | 89.9 | 92.5 | 90.0 |

| Paraesthesias | 100.0 | 95.0 | 86.2 | 82.6 | 96.8 | 97.1 | 90.9 | 93.7 | 93.3 | 90.2 | 90.5 |

| Dysaesthesias | 100.0 | 95.0 | 89.3 | 91.3 | 92.8 | 94.1 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 94.4 | 85.0 |

| Evoked pain, % | |||||||||||

| Static allodynia | 95.8 | 90.0 | 91.5 | 88.3 | 68.7 | 73.5 | 54.5 | 93.6 | 84.8 | 82.0 | 80.0 |

| Dynamic allodynia | 91.7 | 95.0 | 86.2 | 78.3 | 69.6 | 70.6 | 54.5 | 100.0 | 93.5 | 83.7 | 85.0 |

| Thermal allodynia | 70.8 | 60.0 | 85.2 | 68.2 | 52.0 | 61.8 | 45.5 | 78.1 | 65.9 | 71.5 | 75.0 |

| Mechanical hyperalgesia | 84.0 | 85.0 | 89.3 | 78.3 | 81.2 | 73.5 | 77.3 | 90.6 | 86.7 | 86.8 | 71.4 |

| Hyperpathia | 83.3 | 70.0 | 77.8 | 69.6 | 70.3 | 63.6 | 72.7 | 84.4 | 76.7 | 77.5 | 73.7 |

The major cause for uncontrolled pain, as assessed by the pain clinic investigators, was attributed to suboptimal treatment (88%) because of the use of ineffective drugs or subtherapeutic doses (Table 2). The use of ineffective drugs was less common among the patients who were referred by the neurology and neurosurgery departments.

The patients were receiving a mean of 3 drugs; one-third of the patients, regardless of the referral specialty, were receiving 4 or more drugs (Table 4). The most common prescribed drugs were antiepileptics (54%), opiods (40%), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (40%); the latter drugs were more commonly prescribed by specialists in rehabilitation facilities (55%), rheumatologists (50%), and traumatologists (46%) and were less commonly prescribed by neurologists (28%) and primary care physicians (34%). Table 5 shows the doses and treatment duration of the most common drugs that patients were receiving at the time of referral.

Table 4.

Treatment of neuropathic pain by specialty.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 | Primary care N = 118 | Traumatology N = 242 | Neurology N = 56 | Neurosurgery N = 58 | Rehabilitation N = 36 | Rheumatology N = 32 | Other surgeries N = 62 | Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of previous treatments | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.13 ± 1.51 | 2.99 ± 1.44 | 3.21 ± 1.57 | 3.39 ± 1.56 | 3.10 ± 1.18 | 3.09 ± 1.28 | 3.10 ± 1.37 | 2.76 ± 1.49 | 3.13 ± 1.72 |

| 1, % | 11.9 | 15.5 | 12.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 3.3 | 17.6 | 10.9 |

| 2, % | 27.4 | 23.6 | 24.9 | 27.8 | 28.8 | 27.3 | 43.3 | 35.3 | 31.5 |

| 3, % | 25.6 | 29.1 | 24.9 | 27.8 | 30.8 | 27.3 | 20.0 | 21.6 | 27.2 |

| >4, % | 35.1 | 31.8 | 37.6 | 38.9 | 34.6 | 36.4 | 33.3 | 25.5 | 30.4 |

| Treatment at the time of inclusion, % | |||||||||

| Paracetamol | 25.0 | 19.1 | 33.9 | 13.0 | 15.4 | 18.2 | 26.7 | 25.5 | 22.8 |

| NSAIDs | 40.1 | 33.6 | 47.5 | 27.8 | 36.5 | 54.5 | 50.0 | 43.1 | 25.0 |

| Opiods | 39.6 | 41.8 | 40.3 | 38.9 | 55.8 | 33.3 | 53.3 | 17.6 | 35.9 |

| Tramadol | 29.5 | 28.2 | 29.4 | 29.6 | 48.1 | 24.2 | 43.3 | 13.7 | 28.3 |

| Others | 14.8 | 16.4 | 14.9 | 18.5 | 15.4 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 7.8 | 15.2 |

| AED | 54.1 | 56.4 | 48.4 | 81.5 | 69.2 | 48.5 | 43.3 | 41.2 | 56.5 |

| Pragabalin | 26.7 | 21.8 | 29.4 | 33.3 | 28.8 | 24.2 | 23.3 | 23.5 | 25.0 |

| Gabapentin | 23.5 | 28.2 | 19.0 | 31.5 | 34.6 | 15.2 | 10.0 | 17.6 | 30.4 |

| Carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine | 6.3 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 31.5 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 5.4 |

| Other | 4.4 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 5.4 |

| Antidepressants | 19.7 | 24.5 | 15.8 | 31.5 | 17.3 | 9.1 | 20.0 | 17.6 | 25.0 |

| Duloxetine | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 3.9 | 6.5 |

| Tricyclics | 11.3 | 13.6 | 6.3 | 25.9 | 11.5 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 11.8 | 17.4 |

| Other | 4.2 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 3.3 |

| Other drugs | 47.6 | 47.3 | 46.6 | 51.9 | 34.6 | 39.4 | 46.7 | 51.0 | 54.3 |

| Nonpharmacological | 52.0 | 46.4 | 58.8 | 44.4 | 51.9 | 81.8 | 53.3 | 47.1 | 39.1 |

AED: antiepileptic drugs: NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD: standard deviation.

Table 5.

Most common (≥5%) drugs for the treatment of neuropathic pain at the time of referral.

| Drug | % patients | Mean dose (SD) mg/day | Duration (months) mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 21.2 | 2,398.6 (960.1) | 5.5 (6.3) |

| NSAIDs | |||

| Ibuprofen | 17.9 | 1,428.4 (457.2) | 8.5 (13.3) |

| Metamizol | 14.8 | 2,158.8 (1,598.7) | 8.5 (13.3) |

| Diclofenac | 6.3 | 124.9 (34.8) | 8.5 (13.3) |

| Opiods | |||

| Tramadol | 27.1 | 182.9 (110.1) | 12.1 (21.5) |

| Fentanil | 8.6 | 18.5 (25.1) | 7.5 (12.9) |

| AED | |||

| Pragabalin | 27.2 | 244.6 (242.5) | 13.8 (17.4) |

| Gabapentin | 19.0 | 1,297.7 (646.9) | 9.3 (12.0) |

| Carbamazepine | 5.1 | 577.1 (313.5) | 22.2 (27.5) |

| Antidepressants | |||

| Amitriptyline | 10.8 | 36.2 (27.3) | 12.9 (15.4) |

| Duloxetine | 6.1 | 58.3 (22.0) | 8.1 (8.0) |

| Other drugs | |||

| Clonazepam | 5.7 | 2.1 (2.7) | 2.2 (1.0) |

SD: standard deviation.

Patients with uncontrolled pain showed low satisfaction with their treatment with a global satisfaction score of 44 of 100. Treatment effectiveness and the impact of medicine on their everyday life were the areas exhibiting lower satisfaction, with mean scores of 32 and 30, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Treatment satisfaction by specialty.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 | Primary care N = 118 | Traumatology N = 242 | Neurology N = 56 | Neurosurgery N = 58 | Rehabilitation N = 36 | Rheumatology N = 32 | Other surgeries N = 62 | Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiencing side effects, % | 51.7 | 57.8 | 49.3 | 67.9 | 51.9 | 47.1 | 60.0 | 37.3 | 46.3 |

| SATMED-Q dimensions, mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Undesirable side effects | 74.8 ± 29.2 | 72.34 ± 29.08 | 75.14 ± 28.24 | 70.12 ± 28.29 | 70.83 ± 33.14 | 73.51 ± 31.59 | 70.83 ± 31.99 | 84.76 ± 25.44 | 77.95 ± 30.55 |

| Treatment effectiveness | 32.4 ± 25.8 | 34.20 ± 25.72 | 31.93 ± 24.76 | 38.56 ± 28.58 | 32.27 ± 25.52 | 28.23 ± 25.52 | 39.03 ± 24.67 | 39.44 ± 30.54 | 24.24 ± 24.06 |

| Convenience of use | 58.2 ± 25.2 | 60.48 ± 25.32 | 59.91 ± 23.83 | 59.80 ± 24.82 | 53.01 ± 28.79 | 58.47 ± 26.23 | 62.22 ± 22.61 | 60.05 ± 24.73 | 52.06 ± 27.09 |

| Impact on daily living/activities | 30.9 ± 26.6 | 33.41 ± 26.05 | 29.46 ± 26.45 | 35.26 ± 27.45 | 33.83 ± 28.29 | 26.82 ± 24.39 | 34.72 ± 21.00 | 37.77 ± 30.19 | 24.64 ± 25.65 |

| Medical care | 63.9 ± 28.0 | 63.29 ± 29.55 | 62.50 ± 28.26 | 64.66 ± 26.86 | 65.25 ± 27.12 | 59.38 ± 26.94 | 55.83 ± 29.68 | 68.62 ± 29.66 | 68.41 ± 25.97 |

| Global satisfaction | 44.3 ± 30.3 | 50.23 ± 29.60 | 42.69 ± 30.49 | 50.16 ± 29.68 | 44.17 ± 29.08 | 33.59 ± 30.64 | 45.11 ± 28.04 | 52.13 ± 33.31 | 38.68 ± 28.75 |

| Total composite score | 50.7 ± 17.5 | 51.88 ± 17.18 | 50.92 ± 17.11 | 53.36 ± 18.09 | 48.88 ± 18.97 | 47.35 ± 18.98 | 52.32 ± 16.62 | 57.57 ± 20.96 | 46.37 ± 14.96 |

SATMED-Q: Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire; SD: standard deviation.

The number of drugs that the patients were receiving was higher among the patients with central neuropathic pain (3.7), plexopathy (3.5), radiculopathy (3.3), and complex regional pain syndrome (3.2) and was lower among those with diabetic neuropathy (2.3) (Table 7). The use of antiepileptics, especially carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, was higher in patients with trigeminal neuralgia (90.6%); the use of opioids was higher in patients with plexopathy (50%), nerve entrapment syndrome (46%), and radiculopathy (45%). Approximately 50% of the patients with radiculopathy, nerve entrapment syndrome, or complex regional syndrome were receiving NSAIDs. Suboptimal treatment was the major cause for uncontrolled pain, regardless of the clinical entity, but was overrepresented in patients with plexopathy (96%) and in patients with radiculopathy (91%) (Table 7). Overall, the treatment satisfaction was low, and the satisfaction with treatment efficacy was equally low (Table 7).

Table 7.

Pharmacological treatment, reasons for uncontrolled pain, and treatment satisfaction by clinical entity.

| Characteristic | Diabetic neuropathy N = 26 | Other neuropathies N = 22 | Trigeminal neuralgia N = 32 | Other neuralgia N = 24 | Radiculopathy N = 298 | Nerve entrapment syndrome N = 39 | Plexopathy N = 24 | Complex regional pain syndrome N = 36 | Postsurgery/trauma N = 54 | Oncological pain N = 99 | Central neuropathic pain N = 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS, mean ± SD | 77.5 ± 13.4 | 68.6 ± 15.6 | 79.8 ± 18.9 | 73.3 ± 20.0 | 74.3 ± 13.5 | 75.4 ± 13.2 | 77.7 ± 19.4 | 78.3 ± 9.7 | 70.7 ± 17.8 | 74.2 ± 17.7 | 72.7 ± 13.3 |

| WHO-DAS II Interference with life (severe/extreme), % | 52.0 | 52.7 | 42.9 | 39.1 | 46.7 | 38.3 | 52.4 | 67.7 | 33.4 | 30.4 | 66.7 |

| Number of previous treatments, mean ± SD | 2.30 ± 1.26 | 3.00 ± 1.50 | 2.87 ± 1.58 | 2.90 ± 1.48 | 3.32 ± 1.48 | 2.63 ± 1.48 | 3.45 ± 1.47 | 3.23 ± 1.57 | 2.85 ± 1.68 | 2.76 ± 1.23 | 3.65 ± 1.81 |

| Treatment at the time of inclusion, % | |||||||||||

| Paracetamol | 17.4 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 23.8 | 32.0 | 28.6 | 22.7 | 20.0 | 25.5 | 20.9 | 10.0 |

| NSAIDs | 17.4 | 33.3 | 21.9 | 47.6 | 49.6 | 48.6 | 40.9 | 48.6 | 44.7 | 22.0 | 10.0 |

| Opiods | 34.8 | 27.8 | 28.1 | 23.8 | 44.9 | 45.7 | 50.0 | 37.1 | 27.7 | 31.9 | 50.0 |

| Tramadol | 21.7 | 22.2 | 28.1 | 14.3 | 33.5 | 34.3 | 45.5 | 25.7 | 14.9 | 24.2 | 35.0 |

| Others | 13.0 | 11.1 | 3.1 | 9.5 | 15.1 | 14.3 | 18.2 | 20.0 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 30.0 |

| AED | 52.2 | 72.2 | 90.6 | 47.6 | 45.6 | 42.9 | 45.5 | 54.3 | 36.2 | 70.3 | 85.0 |

| Pragabalin | 26.1 | 38.9 | 25.0 | 14.3 | 28.3 | 14.3 | 27.3 | 31.4 | 19.1 | 24.2 | 35.0 |

| Gabapentin | 30.4 | 33.3 | 31.3 | 19.0 | 16.9 | 25.7 | 18.2 | 11.4 | 17.0 | 38.5 | 60.0 |

| Carbamazepine/ oxcarbazepine | 0.0 | 0.0 | 56.3 | 14.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 12.1 | 10.0 |

| Other | 4.3 | 5.6 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 20.0 |

| Antidepressants | 17.4 | 22.2 | 18.8 | 19.0 | 16.2 | 14.3 | 45.5 | 28.6 | 14.9 | 23.1 | 20.0 |

| Duloxetine | 8.7 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 5.0 |

| Tricyclics | 8.7 | 22.2 | 15.6 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 8.6 | 31.8 | 20.0 | 8.5 | 16.5 | 5.0 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 13.6 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 10.0 |

| Other drugs | 34.8 | 44.4 | 43.8 | 52.4 | 50.0 | 37.1 | 40.9 | 37.1 | 44.7 | 48.4 | 55.0 |

| Causes for uncontrolled pain, % | |||||||||||

| Misdiagnosis | 15.4 | 18.2 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 8.4 | 10.3 | 20.8 | 11.1 | 27.8 | 9.1 | 4.8 |

| Nonoptimized treatment | 80.8 | 77.3 | 78.1 | 83.3 | 91.2 | 89.7 | 95.8 | 86.1 | 77.8 | 87.9 | 85.7 |

| Use of ineffective drugs | 61.9 | 29.4 | 20.0 | 45.0 | 48.7 | 57.1 | 39.1 | 48.4 | 69.0 | 36.8 | 11.1 |

| Subtherapeutic dose | 47.6 | 41.2 | 52.0 | 25.0 | 46.1 | 40.0 | 43.5 | 38.7 | 28.6 | 57.5 | 55.6 |

| Other | 9.5 | 41.2 | 44.0 | 40.0 | 24.4 | 17.1 | 30.4 | 25.8 | 19.0 | 21.8 | 50.0 |

| Lack of compliance | 15.4 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 4.2 | 11.1 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 9.5 |

| Intolerance | 0.0 | 9.1 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 19.0 |

| Other | 11.5 | 9.1 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 10.1 | 9.5 |

| SATMED-Q | |||||||||||

| Total score, mean ± SD | 51.0 ± 16.1 | 52.2 ± 18.3 | 50.7 ± 15.6 | 56.5 ± 22.1 | 51.2 ± 17.2 | 53.8 ± 16.3 | 49.7 ± 18.1 | 42.1 ± 14.2 | 49.0 ± 21.3 | 48.2 ± 15.6 | 49.7 ± 19.1 |

| Efficacy, mean ± SD | 26.0 ± 23.9 | 28.2 ± 31.6 | 35.7 ± 25.7 | 33.7 ± 30.5 | 32.7 ± 24.7 | 37.6 ± 24.2 | 34.5 ± 30.3 | 23.9 ± 26.7 | 29.6 ± 27.3 | 30.5 ± 24.0 | 31.6 ± 26.1 |

AED: antiepileptic drugs; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SATMED-Q: Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire; SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analog scale; WHO-DAS II: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II; Yrs: years.

3.3. Impact of Uncontrolled Pain on Psychological Well-Being and Disability

More than half of the patients were diagnosed with depression, and 43% of the patients were diagnosed with anxiety (Table 8). Sleep was also deeply affected among these patients. The patients who were referred to pain clinics by rheumatologists exhibited symptoms that had the greatest impact on their psychological well-being and sleep (Table 8).

Table 8.

Depression, anxiety, and sleep.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 |

Primary care N = 118 |

Traumatology N = 242 |

Neurology N = 56 |

Neurosurgery N = 58 |

Rehabilitation N = 36 |

Rheumatology N = 32 |

Other surgeries N = 62 |

Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-depression (0–21) | |||||||||

| mean ± SD | 10.7 ± 4.6 | 10.2 ± 4.5 | 10.8 ± 4.2 | 10.5 ± 4.7 | 10.8 ± 4.8 | 10.5 ± 4.6 | 12.5 ± 4.3 | 9.2 ± 5.6 | 11.3 ± 5.1 |

| Clinical depression, % | 53.0 | 48.1 | 55.0 | 53.8 | 53.8 | 52.9 | 71.4 | 41.5 | 54.8 |

| HADS-anxiety (0–21) | |||||||||

| mean ± SD | 9.7 ± 4.2 | 9.0 ± 4.0 | 9.8 ± 3.8 | 9.9 ± 4.3 | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 9.8 ± 4.5 | 11.0 ± 3.8 | 9.9 ± 5.0 | 9.4 ± 4.6 |

| Clinical anxiety, % | 43.1% | 32.4 | 45.4 | 44.2 | 34.6 | 51.4 | 63.3 | 43.4 | 43.5 |

| MOS-Sleep, mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Summary index (0–100) | 47.8 ± 19.1 | 43.5 ± 19.2 | 48.8 ± 18.5 | 50.0 ± 20.9 | 49.0 ± 21.1 | 45.4 ± 17.7 | 56.0 ± 12.1 | 45.4 ± 18.9 | 46.1 ± 20.0 |

| Sleep disturbance (0–100) | 51.8 ± 23.1 | 47.7 ± 23.1 | 53.8 ± 22.3 | 51.6 ± 24.7 | 52.1 ± 26.1 | 48.2 ± 24.7 | 63.1 ± 15.8 | 49.1 ± 22.5 | 49.7 ± 23.4 |

| Snoring (0–100) | 38.1 ± 30.4 | 33.3 ± 28.0 | 37.0 ± 30.5 | 37.1 ± 28.9 | 32.9 ± 28.8 | 44.1 ± 28.2 | 39.3 ± 33.2 | 40.4 ± 29.9 | 43.3 ± 34.7 |

| Shortness of breath (0–100) | 24.4 ± 25.8 | 22.7 ± 26.1 | 24.9 ± 24.8 | 28.9 ± 29.8 | 22.7 ± 27.2 | 25.1 ± 23.4 | 27.6 ± 27.0 | 20.0 ± 23.1 | 23.6 ± 27.5 |

| Adequacy of sleep (100–0) | 37.1 ± 27.5 | 43.7 ± 28.7 | 36.2 ± 26.5 | 35.8 ± 28.5 | 34.4 ± 29.0 | 39.1 ± 24.4 | 28.6 ± 21.8 | 36.0 ± 28.3 | 38.6 ± 29.1 |

| Amount of sleep, hours | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 2.5 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.68 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 1.70 | 5.6 ± 1.7 |

| Daytime somnolence (0–100) | 39.5 ± 19.8 | 38.6 ± 18.0 | 38.7 ± 19.9 | 47.2 ± 21.7 | 38.7 ± 20.5 | 37.6 ± 20.7 | 43.1 ± 17.9 | 34.1 ± 18.2 | 40.7 ± 21.1 |

HADS: Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale; MOS-Sleep: the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale; SD: standard deviation.

The proportion of disability among patients with uncontrolled pain was high, with approximately 50% of the patients rating their overall health as bad or very bad and 45% noting that their disease was severely or extremely interfering with their life (Table 9). The difficulties were present most of the time (22 of 30 days) and prevented them from executing their daily activities 15 days a month. The most affected dimensions were life activities either at home or at work (Table 9).

Table 9.

Disability (WHO-DAS II) by specialty.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 728 | Primary care N = 118 | Traumatology N = 242 | Neurology N = 56 | Neurosurgery N = 58 | Rehabilitation N = 36 | Rheumatology N = 32 | Other surgeries N = 62 | Other specialties N = 102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO-DAS II H1-H5 | |||||||||

| Overall health (Bad/very bad), % | 48.9 | 44.9 | 49.6 | 52.7 | 56.6 | 45.7 | 53.5 | 36.4 | 51.0 |

| Interference with life (Severe/extreme), % | 45.3 | 36.3 | 49.3 | 51.0 | 47.0 | 44.1 | 50.0 | 31.5 | 46.8 |

| Duration of difficulties (days), mean ± SD | 22.4 ± 9.9 | 20.29 ± 11.07 | 23.00 ± 9.21 | 21.11 ± 9.97 | 22.10 ± 10.02 | 25.21 ± 8.06 | 22.07 ± 7.62 | 19.89 ± 11.95 | 23.55 ± 9.95 |

| Days totally unable to carry out usual activities/work, mean ± SD | 14.7 ± 11.7 | 11.71 ± 11.54 | 16.23 ± 11.18 | 13.83 ± 11.51 | 15.04 ± 11.29 | 16.35 ± 12.54 | 14.90 ± 11.54 | 13.47 ± 12.54 | 14.44 ± 12.50 |

| Days cutting back or reducing usual activities/work | 19.2 ± 11.1 | 15.76 ± 12.04 | 20.65 ± 10.29 | 17.00 ± 11.46 | 20.02 ± 10.51 | 20.47 ± 11.34 | 19.37 ± 10.33 | 17.72 ± 11.75 | 20.13 ± 11.33 |

| WHO-DAS II dimensions, mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Understanding and communicating | 40.0 ± 24.4 | 37.16 ± 23.79 | 40.12 ± 23.69 | 44.10 ± 26.24 | 40.80 ± 25.38 | 39.64 ± 22.17 | 50.83 ± 19.40 | 35.45 ± 26.11 | 38.82 ± 25.94 |

| Getting around | 57.5 ± 30.4 | 47.18 ± 31.97 | 64.96 ± 26.75 | 51.89 ± 32.74 | 62.74 ± 29.26 | 67.50 ± 31.24 | 66.25 ± 22.06 | 48.41 ± 29.07 | 48.05 ± 32.41 |

| Self-care | 38.6 ± 26.9 | 30.33 ± 24.23 | 42.49 ± 25.34 | 38.99 ± 31.17 | 38.99 ± 22.63 | 45.71 ± 23.69 | 39.44 ± 28.19 | 35.45 ± 29.58 | 35.79 ± 30.46 |

| Getting along with people | 33.5 ± 28.4 | 30.68 ± 28.87 | 34.64 ± 27.10 | 35.85 ± 30.43 | 34.91 ± 28.73 | 28.57 ± 25.10 | 43.33 ± 25.37 | 28.18 ± 27.24 | 33.97 ± 31.79 |

| Life activities, household | 67.2 ± 30.5 | 58.11 ± 34.73 | 72.54 ± 26.25 | 66.04 ± 33.65 | 70.75 ± 26.74 | 67.14 ± 26.96 | 75.00 ± 25.43 | 57.27 ± 31.06 | 63.68 ± 33.77 |

| Life activities, work | 66.2 ± 33.1 | 55.86 ± 36.14 | 72.87 ± 31.00 | 63.21 ± 32.74 | 74.53 ± 27.07 | 61.43 ± 34.48 | 63.79 ± 26.38 | 60.19 ± 35.53 | 63.16 ± 35.14 |

| Participation in society | 60.9 ± 23.1 | 56.31 ± 24.21 | 62.39 ± 22.15 | 63.52 ± 22.89 | 62.58 ± 23.55 | 57.62 ± 19.11 | 68.89 ± 17.36 | 52.42 ± 28.04 | 62.33 ± 22.72 |

SD: standard deviation; WHO-DAS II: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that uncontrolled neuropathic pain is a problem that extends into multiple specialties that address the issue of chronic pain. Uncontrolled neuropathic pain appears to affect patients with clinical entities that are a subsidiary of traumatological care, in which radiculopathy is the most common cause. Other common causes of uncontrolled pain are pain of oncological origin and trigeminal neuralgia. Regardless of the cause and the specialist managing the patient with uncontrolled pain, we observed the following. The impact of the disease is high in terms of disrupting the patients' psychological well-being and disability; the major cause of uncontrolled pain is receiving suboptimal treatment; and the patients are generally dissatisfied with the treatment received.

Traumatologists were by far the primary referral specialists of uncontrolled pain (34%), and radiculopathy was the most common cause (43%) of uncontrolled pain. These findings are consistent with the most common causes of chronic pain in the general population. Thus, according to the survey of pain in Europe, the most frequent location of chronic pain was back pain (42%) and the more frequent cause of pain was herniated or deteriorated discs (15%) and traumatic injuries (12%) [34]. These results overlap with those reported in a previous study on the etiology of neuropathic pain in patients who attended pain clinics in Spain [13]. Although radiculopathy is the most common cause of uncontrolled pain because of its high prevalence as a cause of chronic pain, the presence of trigeminal neuralgia and pain of oncological origin as other common causes of uncontrolled pain is likely due to their refractoriness to current treatments. It is important to note that patients with uncontrolled oncological pain (i.e., pain of malignant origin, radiotherapy- or chemotherapy-induced) were primarily referred by surgical specialties and, surprisingly, by primary care physicians. The management of cancer pain requires the involvement of specialists of multiple disciplines, and anesthesiologists play a key role [35]. Therefore, we would have expected a higher rate of referrals of patients with oncological pain from specialties other than primary care.

The fact that neuropathic pain may be associated with the presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances is well known [36–40]. However, it should be emphasized that high proportions of depression (53%) and anxiety (43%) were found in our sample of patients with uncontrolled pain. Anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances are interrelated in patients with neuropathic pain and may increase the severity of pain [41–43] and contribute to the persistence of neuropathic pain [44]. Therefore, the management of uncontrolled pain should focus not only on the treatment of the underlying disease and its associated pain but also on the appropriate management of the accompanying anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances. Our results emphasize the enormous impact of uncontrolled pain on the patients' daily life. Half of the patients rated their overall health as bad or very bad, and 45% noted that their condition severely or extremely interfered with their life. The interference was high, regardless of the specialty or the pain etiology. However, regarding the etiology, the interference was higher for the complex regional pain syndrome and central neuropathic pain. We believe that this higher interference in these clinical entities more closely correlated with the underlying disease than to the pain itself because, with the exception of complex regional pain syndrome, the etiologies associated with the highest pain intensity are not those associated with the highest interference. The difficulties associated with uncontrolled pain were present most days, and the most severe impact was on daily activities at home or at work, that is, being totally unable to conduct their usual activities half of the days in the previous month. Although it was not specifically evaluated in our study, as it had been described for neuropathic pain in general [13, 14, 45], this degree of disability is likely to contribute to the high costs associated with neuropathic pain.

The investigators from the pain clinics determined that the main reason for uncontrolled pain was because the patients were receiving suboptimal treatment; that is, the patients received either ineffective drugs or subtherapeutic doses of the drugs. For instance, NSAIDs were used to treat more than 40% of the patients, and carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, the first-line treatments for trigeminal neuralgia [16], were only used by 56% of the patients with that condition. However, regarding the latter drug, it is possible that those patients were receiving a second- or third-line treatment including surgery. Despite NSAIDs are considered ineffective and are not recommended for treating neuropathic pain [16, 19, 20, 46, 47], their use is common in patients with these conditions as it has been reported in several studies from different countries [18, 48, 49]. Noteworthy, in our study NSAIDs were used at high doses (e.g., over 1,400 mg/day of ibuprofen). The use of NSAIDs contributes to the suboptimal treatment of neuropathic and increases the risk of experiencing important adverse reactions. Suboptimal treatment has been previously described in patients with neuropathic pain who attended primary care clinics [4, 18, 50, 51]. According to our results, suboptimal treatment seems to affect all of the specialties involved in the care of patients with neuropathic pain. Treatment satisfaction was poor across several specialties and clinical entities. The areas that were rated with lower satisfaction were treatment effectiveness and impact on daily activities, and these areas are closely related. Although satisfaction with medical care received a higher rating than impact on daily activities, the former issue seemed to be an area for improvement. Despite the fact that most patients experienced treatment side-effects according to the SATMED-Q, medical treatment was rated with greater satisfaction; however, it should be noticed that acute side effects were not reflected in that evaluation.

The major limitation in our study was the definition of uncontrolled pain that was entirely based on the subjective evaluation of the investigators from the pain clinics. We accepted this subjective evaluation because there is no standard definition of refractory neuropathic pain [21]. Recently, a group of experts tried to achieve consensus on this matter [52]; according to that consensus, to classify a neuropathic pain as refractory, “it should have had a trial of treatment with at least four drugs of known effectiveness, each drug should have been tried at least three months or until side effects prevent adequate dosage, and despite the above treatment, the intensity of pain should have reduced by less than 30%, should remain at a level of at least 5 on a 0–10 scale, and/or should continue to contribute significantly to poor quality of life” [52]. Because the patients in our study were considered to have received suboptimal treatment, it is difficult to meet those criteria. However, the patients' pain was clearly persistent, severe, disabling, and, therefore, uncontrolled.

Overall, our results showed that uncontrolled neuropathic pain is a common phenomenon among the specialties that address these clinical entities, and regardless of its etiology, uncontrolled neuropathic pain is associated with a dramatic impact on patient well-being. A definite need exists for improving the management of neuropathic pain in all of these specialties, which should not be limited to the improvement of pain but also should be extended to the management of psychological symptoms and possibly to the improvement of the doctor-patient relationship.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by Pfizer España. The authors thank Fernando Rico-Villademoros from Cociente S.L. for his assistance in the preparation of the draft of this paper; this assistance was funded by Pfizer, S.L.U.

Conflict of Interests

Dr. De Andrés has not conflict of interests relevant to this paper; Dr. De la Calle has received consulting/lecture fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Grunenthal, Prostrakan, Mundipharma, Eisai, Janssen-Cilag, Cardiva, and Pfizer; Dr. Pérez and López are employees of Pfizer.

References

- 1.Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1630–1635. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. Journal of Pain. 2006;7(4):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136(3):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez C, Saldaña MT, Navarro A, Vilardaga I, Rejas J. Prevalence and characterization of neuropathic pain in a primary-care setting in spain: a cross-sectional, multicentre, observational study. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2009;29(7):441–450. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200929070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter GT, Galer BS. Advances in the management of neuropathic pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2001;12(2):447–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(8):807–819. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jay GW, Barkin RL. Neuropathic pain: etiology, pathophysiology, mechanisms, and evaluations. Disease-a-Month. 2014;60:6–47. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gore M, Brandenburg NA, Hoffman DL, Tai K-S, Stacey B. Burden of illness in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: the patients' perspectives. Journal of Pain. 2006;7(12):892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gálvez R, Marsal C, Vidal J, Ruiz M, Rejas J. Cross-sectional evaluation of patient functioning and health-related quality of life in patients with neuropathic pain under standard care conditions. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11(3):244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott AM, Toelle TR, Rowbotham DJ, Schaefer CP, Dukes EM. The burden of neuropathic pain: results from a cross-sectional survey. European Journal of Pain. 2006;10(2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attal N, Lanteri-Minet M, Laurent B, Fermanian J, Bouhassira D. The specific disease burden of neuropathic pain: results of a French nationwide survey. Pain. 2011;152(12):2836–2843. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith BH, Torrance N. Epidemiology of neuropathic pain and its impact on quality of life. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2012;16:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodríguez MJ, García AJ. A registry of the aetiology and costs of neuropathic pain in pain clinics: results of the registry of aetiologies and costs (REC) in neuropathic pain disorders study. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2007;27(11):771–782. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200727110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger A, Dukes EM, Oster G. Clinical characteristics and economic costs of patients with painful neuropathic disorders. Journal of Pain. 2004;5(3):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langley PC, Van Litsenburg C, Cappelleri JC, Carroll D. The burden associated with neuropathic pain in Western Europe. Journal of Medical Economics. 2013;16:85–95. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.729548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. European Journal of Neurology. 2010;17(9):1113–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harden N, Cohen M. Unmet needs in the management of neuropathic pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25:S12–S17. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gore M, Dukes E, Rowbotham DJ, Tai KS, Leslie D. Clinical characteristics and pain management among patients with painful peripheral neuropathic disorders in general practice settings. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11(6):652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline. 96th edition. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010. Neuropathic pain: the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2010;85:S3–S14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor RS. Epidemiology of refractory neuropathic pain. Pain Practice. 2006;6(1):22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4) Pain. 2005;114(1-2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, et al. Development and validation of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory. Pain. 2004;108(3):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez C, Galvez R, Huelbes S, et al. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the DN4 (Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions) questionnaire for differential diagnosis of pain syndromes associated to a neuropathic or somatic component. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5, article 66 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero MJ, Blanch J, Peri JM, de Pablo J, Pintor L, Bulbena A. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in a Spanish population. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;25(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hays RD, Stewart AL. Sleep measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press; 1992. pp. 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rejas J, Ribera MV, Ruiz M, Masrramón X. Psychometric properties of the MOS (Medical Outcomes Study) Sleep Scale in patients with neuropathic pain. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11(3):329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II. 12-Item Self-Administered Version. Geneve, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luciano JV, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Fernández A, Serrano-Blanco A, Roca M, Haro JM. Psychometric properties of the twelve item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II) in Spanish primary care patients with a first major depressive episode. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;121(1-2):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vázquez-Barquero JL, Vázquez Bourgón E, Herrera Castanedo S, et al. Spanish version of the new World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II, (WHO-DAS-II): initial phase of development and pilot study. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria. 2000;28(2):77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rejas J, Ruiz MA, Pardo A, Soto J. Minimally important difference of the Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire (SATMED-Q) BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11, article 142 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz MA, Pardo A, Rejas J, Soto J, Villasante F, Aranguren JL. Development and validation of the “treatment satisfaction with medicines questionnaire” (SATMED-Q) Value in Health. 2008;11(5):913–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fricker J. Pain in Europe. A Report. 2012

- 35.Practice guidelines for cancer pain management. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Pain Management, Cancer Pain Section. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(5):1243–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Argoff CE. The coexistence of neuropathic pain, sleep, and psychiatric disorders: a novel treatment approach. The Clinical journal of pain. 2007;23(1):15–22. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210945.27052.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gore M, Brandenburg NA, Dukes E, Hoffman DL, Tai K-S, Stacey B. Pain severity in diabetic peripheral neuropathy is associated with patient functioning, symptom levels of anxiety and depression, and sleep. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;30(4):374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain R, Jain S, Raison CL, Maletic V. Painful diabetic neuropathy is more than pain alone: examining the role of anxiety and depression as mediators and complicators. Current Diabetes Reports. 2011;11(4):275–284. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emery PC, Wilson KG, Kowal J. Major depressive disorder and sleep disturbance in patients with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19:35–41. doi: 10.1155/2014/480859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gormsen L, Rosenberg R, Bach FW, Jensen TS. Depression, anxiety, health-related quality of life and pain in patients with chronic fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. European Journal of Pain. 2010;14(127):127.e1–127.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D’Eon JL, Mikail SF, Emery PC. Major depression and insomnia in chronic pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18(2):77–83. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2004;8(2):119–132. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cornwall A, Donderi DC. The effect of experimentally induced anxiety on the experience of pressure pain. Pain. 1988;35(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boogaard S, Heymans MW, Patijn J, et al. Predictors for persistent neuropathic pain—a delphi survey. Pain Physician. 2011;14(6):559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarberg B, Billington R. Consequences of neuropathic pain: quality-of-life issues and associated costs. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12:S263–S268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758–1765. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain—consensus statement and guidelines from the canadian pain society. Pain Research and Management. 2007;12(1):13–21. doi: 10.1155/2007/730785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dieleman JP, Kerklaan J, Huygen FJ, Bouma PA, Sturkenboom MCJM. Incidence rates and treatment of neuropathic pain conditions in the general population. Pain. 2008;137(3):681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berger A, Sadosky A, Dukes E, Edelsberg J, Oster G. Clinical characteristics and patterns of healthcare utilization in patients with painful neuropathic disorders in UK general practice: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurology. 2012;12, article 8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tölle T, Dukes E, Sadosky A. Patient burden of trigeminal neuralgia: results from a cross-sectional survey of health state impairment and treatment patterns in six European countries. Pain Practice. 2006;6(3):153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tölle T, Xu X, Sadosky AB. Painful diabetic neuropathy: a cross-sectional survey of health state impairment and treatment patterns. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2006;20(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith BH, Torrance N, Ferguson JA, et al. Towards a definition of refractory neuropathic pain for epidemiological research. An international Delphi survey of experts. BMC Neurology. 2012;12, article 29 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]