Abstract

The antiparasitic activity of azole and new 4-aminopyridine derivatives has been investigated. The imidazoles 1 and 3–5 showed a potent in vitro antichagasic activity with IC50 values in the low nanomolar concentration range. The (S)-1, (S)-3, and (S)-5 enantiomers showed (up to) a thousand-fold higher activity than the reference drug benznidazole and furthermore low cytotoxicity on rat myogenic L6 cells.

Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, CYP51, antiparasitic activity, Chagas disease, azole, aminopyridine

Chagas disease (CD) is one of the most important neglected tropical disorders, caused by the Kinetoplastid parasite Trypanosoma cruzi,1 and approximately 10 million people worldwide are estimated to be infected.2 CD is a complex anthropozoonosis transmitted to humans by blood-sucking insects of the Triatominae subfamily (mainly Triatoma infestans, Rhodnius prolixus, and Triatoma dimidiatae).3 Currently, the treatment of CD is restricted to nifurtimox and benznidazole used only in the acute phase. The clinical efficacy in chronic patients is limited and controversial, and the undesirable side effects of both drugs are a major drawback in their use.4,5 To date, posaconazole and E1224, a pro-drug of ravuconazole, are in phase 2 of clinical trials for chronic Chagas disease treatment.6 However, the development of new effective and safe drugs is urgent because of the lack of vaccines, the inadequate chemotherapy, the large number of infected people, and their migration toward nonendemic countries.

Similar to fungi and yeasts, Kinetoplastides are strictly dependent on endogenously produced sterols, essential cellular components, that modulate membrane fluidity/permeability and also play multiple regulatory functions related to cell division, growth, and developmental processes. Sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) is an essential enzyme in sterol biosynthesis and its inhibition causes the block of sterol production and the accumulation of toxic methylated sterol precursors followed by pathogen growth arrest and death.7,8

For these reasons, CYP51 of T. cruzi (CYP51Tc) is a highly drug-targetable enzyme for the rational design of new antitrypanosomal drugs. Currently, antifungal azoles (i.e., ketoconazole, fluconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole) are known as CYP51Tc inhibitors due to the presence of an imidazole or triazole ring able to coordinate the heme-iron.9,10 Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that N-heterocyclic rings can be effectively replaced by 3-pyridyl or 4-pyridyl moieties.11−13

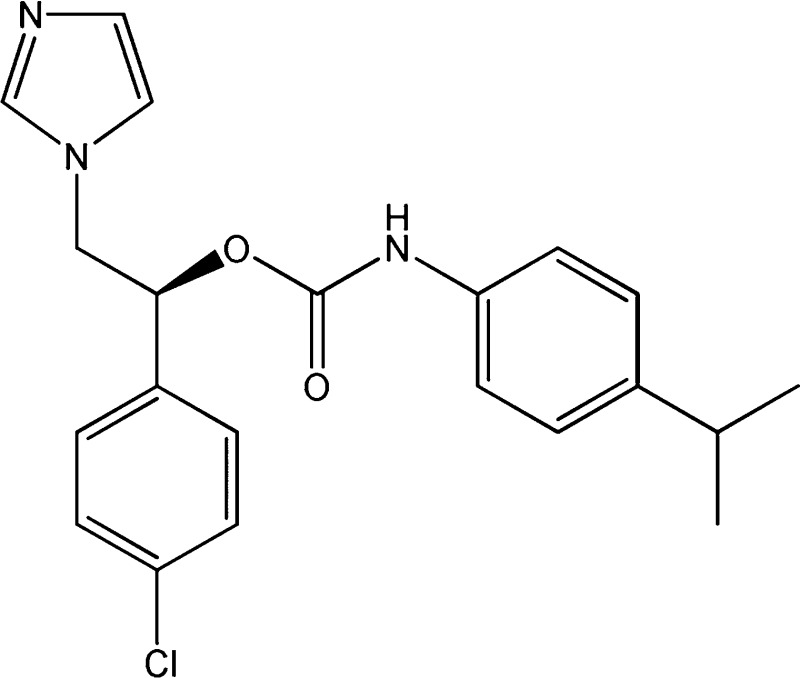

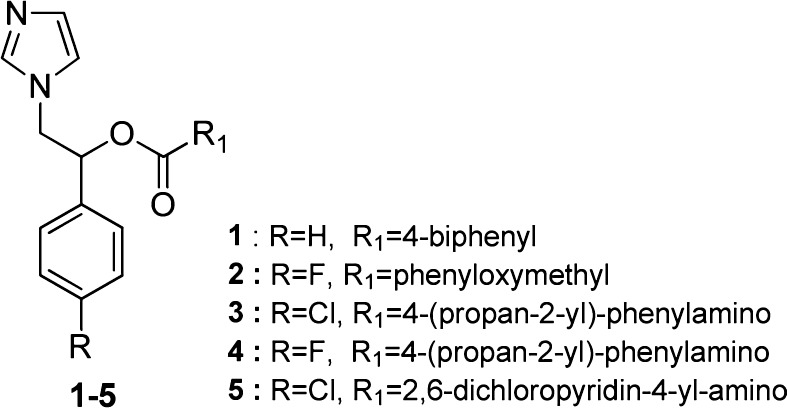

We have selected eight compounds available from our laboratory library: racemic 1-imidazolyl-2-phenylethanol derivatives14 (1–5) (Figure 1) and new 4-aminopyridines (6–8) (Scheme 1). Compounds 1–5 belonging to azole class have been chosen for their structural similarity with CYP51Tc inhibitors; the new 4-aminopyridines (6–8), second generation compounds, have been selected for the presence of the N-4-pyridyl moiety able to interact with the CYP51Tc active site, as previously reported.12 Compounds 1–8 have a nitrogen atom for the heme-iron coordination and hydrophobic moieties able to interact with lipophilic tunnel in the CYP51Tc active site. Here, we report the evaluation of their antiparasitic activity.

Figure 1.

Compounds 1–5 described in this study.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 6–8.

(a) TEA, triphosgene, anhydrous benzene, reflux, 5 h; (b) metronidazole for compound 6, 12 h, r.t. (yield 68%); 2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethanol for compounds 7 (yield 70%) and 8 (yield 60%), 12 h at r.t.

Compounds 1–5 have been prepared as previously reported.14 Compound 6 was obtained by reaction of metronidazole with 3-bromo-4-aminopyridine previously activated with triphosgene, in anhydrous benzene; 7 and 8 were similarly obtained by 2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethanol with 2,6-dichloro-4-aminopyridine and 2-chloro-4-aminopyridine, respectively (Scheme 1).

The biological activity of the selected compounds has been evaluated as reported elsewhere15 against different parasites: T. brucei rhodesiense STIB 900 trypomastigote stage; T. cruzi Tulahuen C2C4 amastigote stage; L. donovani MHOM-ET-67/L82 amastigote stage; P. falciparum K1 erythrocytic stages. Furthermore, the cytotoxic activity against cultured rat L6 myogenic cells was determined (Table 1). The reported data showed that 1 and 3–5 possess high activity toward T. cruzi with IC50 values from 5.0 to 36.0 nM; 3 and 4 turned out to be the most active compounds with an IC50 of 5.0 nM. Furthermore, 1 and 3–5 proved to be highly selective against T. cruzi, as evidenced by low IC50 values compared to the other studied parasites, characterized by low cytotoxicity with IC50 values ranging from 13.0 to 27.2 μM. The new 4-aminopyridine derivatives 6–8 showed lower antiparasitic activity than the imidazoles 1–5.

Table 1. In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity and Cytotoxicity of 1–8 and Reference Drugs; Data Represent IC50 Values Given in μM.

| compd | Tba | Tcb | Ldc | Pfd | L6e | SIf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42.1 | 0.014 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 23.6 | 1686 |

| 2 | 293.8 | 24.4 | 17.3 | 36.7 | 182.5 | 7.5 |

| 3 | 18.2 | 0.005 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 13.0 | 2600 |

| 4 | 19.1 | 0.005 | 15.0 | 4.6 | 16.8 | 3360 |

| 5 | 34.0 | 0.036 | 11.4 | 1.5 | 27.2 | 756 |

| 6 | 138.9 | 48.4 | 85.1 | 60.2 | 222.1 | 4.6 |

| 7 | 117.4 | 133.1 | 122.7 | 23.1 | 79.3 | 0.6 |

| 8 | 230.3 | 175.3 | 190.4 | 79.8 | 237.6 | 1.3 |

| ref drugg | MEL 0.0075 | BNZ 1.671 | MIL 0.366 | CHL 0.328 | PDT 0.001 |

T. brucei rhodesiense STIB 900 trypomastigote stage.

T. cruzi Tulahuen C2C4 amastigote stage.

L. donovani MHOM-ET-67/L82 amastigote stage.

P. falciparum K1 erythrocytic stages.

Rat myogenic L6 cells.

SI = selectivity index, IC50L6/IC50Tc.

MEL = melarsoprol; BNZ = benznidazole; MIL = miltefosine; CHL = chloroquine; PDT = podophyllotoxin.

The high activity of the racemic azole derivatives prompted us to define the differences in the antitrypanosomal activity of the single enantiomers.

Compounds 1, 3, and 5 have been selected and pure (R)-1, (S)-1, (R)-3, (S)-3, (R)-5, and (S)-5 have been prepared as previously described for racemic compounds14 from the corresponding enantiomeric 1-(phenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethanols obtained by modification of a reported procedure.16 The following enantiomeric purity was observed: (R)-1 98.0% ee; (S)-1 98.0% ee; (R)-3 98.5% ee; (S)-3 98.5% ee; (R)-5 98.8% ee; (S)-5 98.8% ee (see Supporting Information).

The antiparasitic activity of pure enantiomers is reported in Table 2 and clearly indicate that both the (R) and (S) enantiomers are highly active and that the biological activity is mainly due to the (S) enantiomers, indeed (S)-1 and (S)-3 show IC50 values 50–60 times lower than the corresponding (R) enantiomers. The carbamate (S)-3 was found to be the most active compound with an IC50 of 1.8 nM vs T. cruzi, resulting in a molar basis approximately a thousand-fold more active than benznidazole. It is noteworthy that all compounds showed a low toxicity toward L6 cells, including the most active azole derivatives, 1 and 3–5, and the corresponding pure enantiomers.

Table 2. In Vitro Activity of Compounds 1, 3 and 5 and Their Pure Enantiomers against T. cruzi; the Cytotoxic Activity on L6 Cells Is Also Given; Data Represent IC50 Values in μM with Standard Deviation (SD).

| compd | Tca | SD | L6b | SD | SIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0149 | 0.0109 | 23.59 | 5.92 | 1583 |

| (R)-1 | 0.1927 | 0.1167 | 27.50 | 4.89 | 143 |

| (S)-1 | 0.0038 | 0.0030 | 18.24 | 1.82 | 4800 |

| 3 | 0.0052 | 0.0031 | 12.97 | 0.73 | 2494 |

| (R)-3 | 0.1120 | 0.0469 | 13.96 | 1.77 | 125 |

| (S)-3 | 0.0018 | 0.0008 | 13.44 | 2.63 | 7467 |

| 5 | 0.0364 | 0.0170 | 27.25 | 3.33 | 749 |

| (R)-5 | 0.0972 | 0.0340 | 15.38 | 4.83 | 158 |

| (S)-5 | 0.0236 | 0.0143 | 31.65 | 5.00 | 1341 |

T. cruzi Tulahuen C2C4 amastigote stage.

Rat myogenic L6 cells.

SI = selectivity index, IC50L6/IC50Tc.

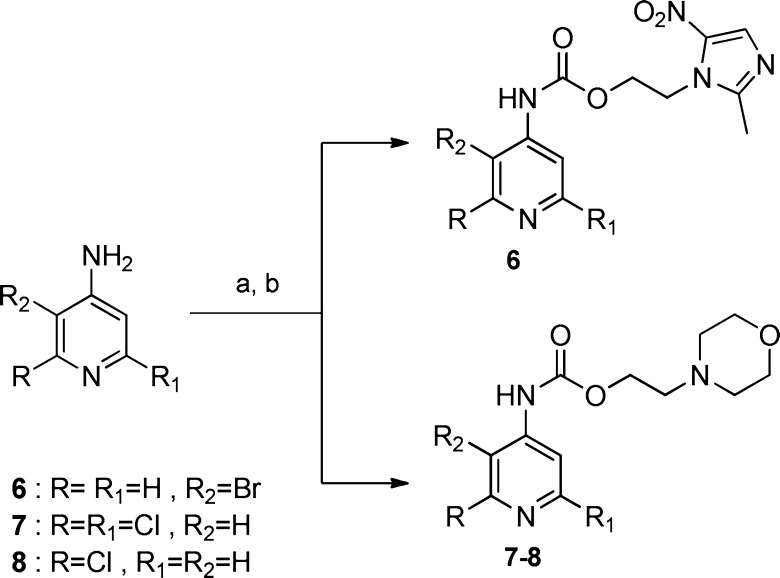

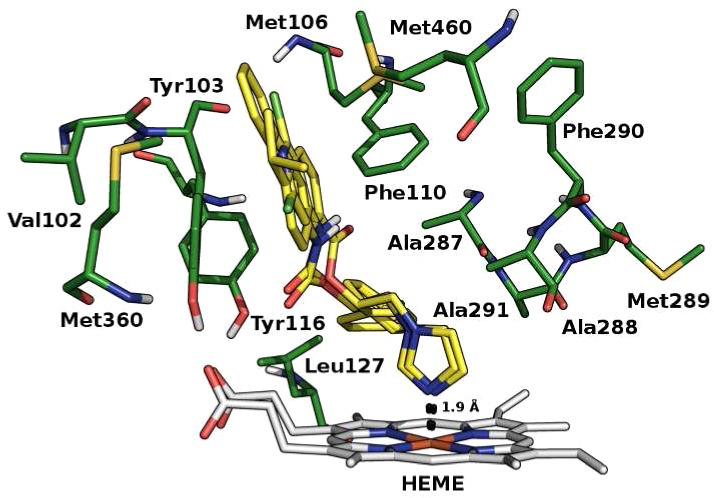

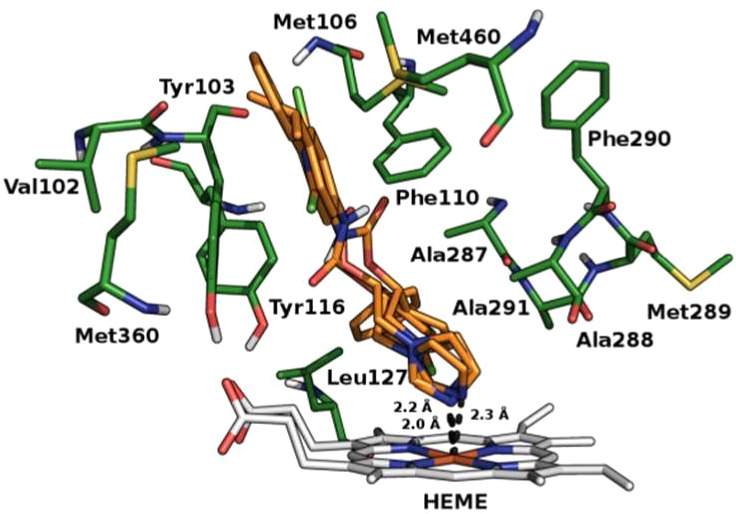

Furthermore, on the basis of the structural similarity between the studied compounds and the current CYP51Tc inhibitors, a docking study of compounds 1–8 against the energy minimized structure of CYP51Tc (PDB ID: 2WX2), CYP51Tb (PDB ID: 3GW9), and CYP51Li (PDB ID: 3L4D; L. infantum belonging to L. donovani complex) was performed. Proteins pretreatment was performed by means of the Protein Preparation Wizard tool of Maestro 9.2 suite17 and the energy minimization using Macromodel18 with the OPLS2005 force field. Docking calculations were performed by means of GOLD5.119 using the ASP scoring function because it was the one that best reproduced the crystallographic pose of cocrystallized ligands. In the CYP51Tc active site, 1, 3, and 5 are mostly stabilized by the coordination of the nitrogen in position 3 of the imidazolic ring to heme-iron and by hydrophobic interactions in the pocket formed by Val102, Tyr103, Met106, Phe110, Tyr116, Leu127, Ala287, Ala288, Met289, Phe290, Ala291, Met360, and Met460. Compound 2 belongs to the same class of compounds 1, 3, and 5, coordinating the heme-iron with the N3 of the imidazolic ring. The lack of its activity could be ascribed to the loss of most of the hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the other active molecules in the pocket described just above. The difference in the activity between (R) and (S) enantiomers of the most active compounds could be ascribed to the better coordination of the imidazolic ring to the heme-iron of (S) enantiomers than that of (R) ones. From our docking calculations, the N3 of the imidazolic ring in all (S) enantiomers coordinate the heme-iron in about 1.9 Å distance, while in (R) enantiomers, the light difference in the conformation and the consequent rotation of the N3 cause a less favored coordination (e.g., 2.0 Å for compound (R)-5, 2.2 Å for compound (R)-1, and 2.3 Å compound (R)-3 approximately) (Figures 2–4). The high selectivity of compounds 1, 3, and 5 toward T. cruzi over T. brucei and L. donovani is probably due to the active site volume and surface area smaller in T. brucei and L. donovani than in T. cruzi that could favor their access in the active site.20 The aminopyridines 6–8 do not show an interesting CYP51Tc inhibitory activity, probably because of the lack of the heme-iron coordination (see Figure S4 in Supporting Information).

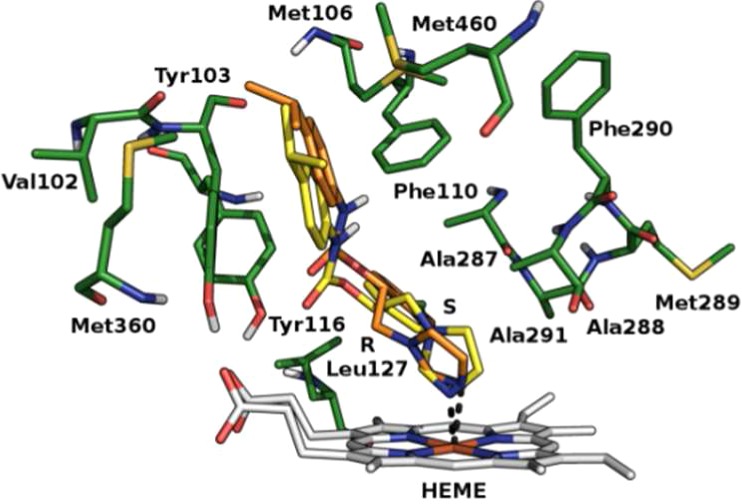

Figure 2.

Binding mode of (S) enantiomers. The protein and the heme prosthetic group (CYP51Tc) are represented in green and gray, respectively; compounds 1, 3, and 5 in yellow. The distance between the N3 of the imidazolic ring and the heme-iron is represented in black dots.

Figure 4.

Different conformations in the CYP51Tc active site of the compound 3; (R)-3 shown in orange and (S)-3 in yellow.

Figure 3.

Binding mode of (R)enantiomers. The protein and the heme prosthetic group (CYP51Tc) are represented in green and gray, respectively; compounds 1, 3, and 5 in orange. The distance between the N3 of the imidazolic ring and the heme-iron is represented in black dots.

A preliminary study on hepatic metabolism has been carried out on the most active (S)-1 and (S)-3. The results have demonstred that (S)-3 is oxidized but not hydrolyzed by the CYP-dependent metabolism. On the contrary, the ester moiety of (S)-1 is hydrolyzed by the CYP enzyme family, and the product is eliminated through the phase 1 metabolism. It has been previously demonstrated that easy metabolized molecules are not CYP inhibitors nor suicide substrate.21−23 Hence, those compounds could be considered not to be toxic for the human liver.

The reported results have evidenced that the azole compounds 1 and 3–5 exert a potent in vitro antichagasic activity showing IC50 values in the low nanomolar concentration range.

The (S) enantiomers are more active than the corresponding (R); in addition, (S)-3 showed an activity a thousand times higher than the reference drug benznidazole. Furthermore, all compounds showed low toxic effects on rat myogenic L6 cells.

Moreover, the docking studies are consistent with the hypothesis of CYP51Tc inhibition, and they agree with the higher activity of (S) enantiomers over (R) enantiomers and the high selectivity vs T. cruzi. These molecules represent an excellent starting point in the development of cheap, easy workup and highly active antitrypanosomal drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roberto Cirilli (Dipartimento del Farmaco, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) for the chiral HPLC analysis. We thank Prof. S. Fornarini and Miss V. Lilla (Dipartimento of “Chimica e Tecnologie del Farmaco” Sapienza University of Rome, Italy) for obtaining the mass spectra.

Supporting Information Available

All synthetic procedures, molecular docking, and biological assay details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This research was financially supported by grants from Sapienza, Università di Roma Progetti di Ricerca di Ateneo, and by Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hotez P. J.; Molyneux D. H.; Fenwick A.; Kumaresan J.; Ehrlich Sachs S.; Sachs J. D.; Savioli L. Control of neglected tropical diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1018–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564090_eng.pdf (accessed Nov 15, 2012).

- Zeledón R.; Rabinovich J. E. Chagas’ disease: an ecological appraisal with special emphasis on its insect vectors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1981, 26, 101–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C.; Montgomery S. P.; Herwaldt B. L.; Rassi A. Jr.; Marin-Neto J. A.; Dantas R. O.; Maguire J. H.; Acquatella H.; Morillo C.; Kirchhoff L. V.; Gilman R. H.; Reyes P. A.; Salvatella R.; Moore A. C. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 2171–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina J. A. Specific chemotherapy of Chagas disease: relevance, current limitations and new approaches. Acta Trop. 2010, 115, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrial.gov. Proof-of-concept study of E1224 to treat adult patients with Chagas disease. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01489228?term=ravuconazole&rank=2 (accessed Apr 16, 2013).

- De Souza W.; Rodrigues J. C. F. Sterol biosynthesis pathway as target for antitrypanosomatid drugs. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009, 642–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva G. I.; Villalta F.; Waterman M. R. Targeting Trypanosoma cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51). Adv. Parasit. 2011, 75, 65–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva G. I.; Hargrove T. Y.; Anderson S.; Kleshchenko Y.; Furtak V.; Wawrzak Z.; Villalta F.; Waterman M. R. Structural insights into inhibition of sterol 14α-demethylase in the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 2853325582–25590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. K.; Leung S. S. F.; Guilbert C.; Jacobson M. P.; McKerrow J. H.; Podust L. M. Structural characterization of CYP51 from Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma brucei bound to the antifungal drugs posaconazole and fluconazole. PLoS Neglect. Trop. D 2010, 44e651. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilleke S. S.; Calvet C. M.; Johnston J. B.; Chen C. K.; Erenburg G.; Gut J.; Engel J. C.; Ang K. K. H.; Mulvaney J.; Chen S.; Arkin M. R.; McKerrow J. H.; Podust L. M. Diverse inhibitor chemotypes targeting Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51. PLoS Neglect. Trop. D 2012, 67e1736. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. K.; Doyle P. S.; Yermalitskaya L. V.; Mackey Z. B.; Ang K. K. H.; McKerrow J. H.; Podust L. M. Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 inhibitor derived from a Mycobacterium tuberculosis screen hit. PLoS Neglect. Trop. D 2009, 32e372. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva G. I.; Hargrove T. Y.; Kleshchenko Y.; Nes W. D.; Villalta F.; Waterman M. R. CYP51: A major drug target in the cytochrome P450 superfamily. Lipids 2008, 43, 1117–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vita D.; Scipione L.; Tortorella S.; Mellini P.; Di Rienzo B.; Simonetti G.; D’Auria F. D.; Panella S.; Cirilli R.; Di Santo R.; Palamara A. Synthesis and antifungal activity of a new series of 2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylethanol derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 49, 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan I.; Şener B.; Kaiser M.; Brun R.; Tasdemir D. Inhibitory activity of marine sponge-derived natural products against parasitic protozoa. Mar. Drugs. 2010, 8, 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon I. C.; Ramsden J. A. An efficient catalytic asymmetric route to 1-aryl-2-imidazol-1-yl-ethanols. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2005, 9, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, version 9.2; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, 2011.

- Macromodel, version 9.2; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, 2011.

- Jones G.; Willet P.; Glen R. C. Molecular recognition of receptor size using a genetic algorithm with a description of desolvation. J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 245, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove T. Y.; Wawrzak Z.; Liu J.; Nes W. D.; Waterman M. R.; Lepesheva G. I. Substrate preferences and catalytic parameters determined by structural characteristics of sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) from Leishmania infantum. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 26838–26848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurima-Romet M.; Crawford K.; Cyr T.; Inaba T. Terfenadine metabolism in human liver: in vitro inhibition by macrolide antibiotics and azole antifungals. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1994, 22, 849–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandel C.; Lang C. C.; Cowart D. C.; Girard A. F.; Bramer S.; Flockhart D. A.; Wood A. J. Effect of CYP3A inhibition on vesnarinone metabolism in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 63, 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando R. R. Mechanism-based enzyme inactivators. Pharmacol. Rev. 1984, 36, 111–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.