Abstract

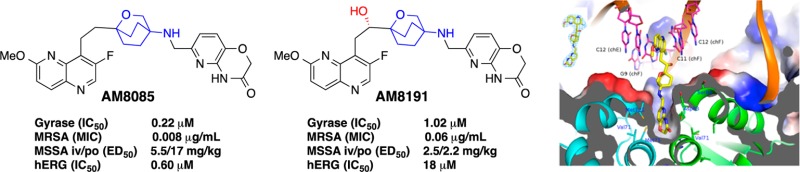

Bacterial resistance is eroding the clinical utility of existing antibiotics necessitating the discovery of new agents. Bacterial type II topoisomerase is a clinically validated, highly effective, and proven drug target. This target is amenable to inhibition by diverse classes of inhibitors with alternative and distinct binding sites to quinolone antibiotics, thus enabling the development of agents that lack cross-resistance to quinolones. Described here are novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors (NBTIs), which are a new class of gyrase and topo IV inhibitors and consist of three distinct structural moieties. The substitution of the linker moiety led to discovery of potent broad-spectrum NBTIs with reduced off-target activity (hERG IC50 > 18 μM) and improved physical properties. AM8191 is bactericidal and selectively inhibits DNA synthesis and Staphylococcus aureus gyrase (IC50 = 1.02 μM) and topo IV (IC50 = 10.4 μM). AM8191 showed parenteral and oral efficacy (ED50) at less than 2.5 mg/kg doses in a S. aureus murine infection model. A cocrystal structure of AM8191 bound to S. aureus DNA-gyrase showed binding interactions similar to that reported for GSK299423, displaying a key contact of Asp83 with the basic amine at position-7 of the linker.

Keywords: Antibacterial, broad spectrum, novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors, NBTI, gyrase inhibitors, topoisomerase IV inhibitors, oxabicyclooctane

Bacterial resistance to current antibiotics continues to increase leaving many antibiotics ineffective.1,2 This creates a profound global threat and necessitates the discovery of new antibiotics with novel modes of action as critical. Bacterial type II topoisomerases (DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV) are clinically validated targets represented by a series of clinical agents with different binding sites.3 Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, 1, Chart 1) are highly successful antibiotics that bind to gyrase A and topoisomerase IV (ParC) subunits, whereas the coumarin (e.g., novobiocin; the other most prominent topo II inhibitor, 2) class of antibiotics binds to gyrase B and topoisomerase IV (ParE), the catalytic subunits.3 Of all the validated bacterial targets, bacterial type II topoisomerases have been amenable to inhibition by diverse structural classes of inhibitors without showing significant cross-resistance to each other due to their action at alternative and distinct binding sites.3 Several novel (nonfluoroquinolone) bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitors (NBTIs) have been recently described.4 These inhibitors bind to different sites of gyrase A and ParC and generally do not show cross-resistance to fluoroquinolones.5−15 The alternative-binding site of these inhibitors was demonstrated by the X-ray crystal structure of one of the inhibitors (GSK299423, 3) bound to DNA-bound gyrase complex of S. aureus.5 Several of the NBTIs (e.g., NXL101) entered clinical development but were discontinued due to hERG binding and associated qTC prolongation.8

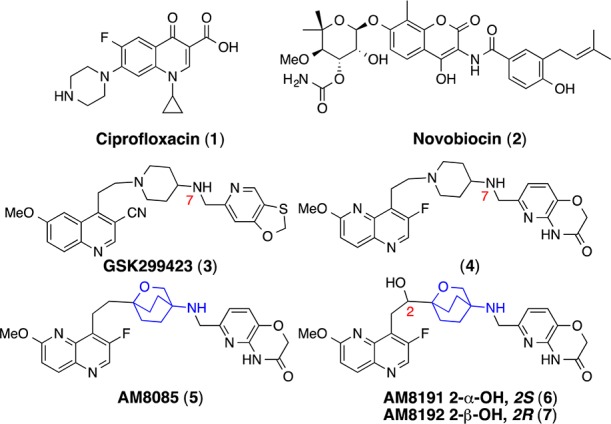

Chart 1. Chemical Structures of NBTIs.

NBTIs consist of three structural moieties: A left-hand site (LHS) aromatic heterocycle, a right-hand side (RHS) aromatic heterocycle, and both connected by a 8-atom central linker. The hallmark of this linker is the strategic placement of a basic nitrogen atom at position-7 that shows a salt-bridge interaction with the Asp83 in the X-ray crystal structure.5 4-Amino-piperidine (4) and 4-amino-cyclohexyl linkers dominate NBTIs.5−15 Recently, 3-amino-6-alkyl-pyran linked NBTIs were reported.16 We embarked on finding alternative linkers and report herein the discovery of an oxabicyclooctane linker (e.g., 5–7) with reduced basicity and attenuated hERG activity. The addition of a hydroxyl group at C-2 (e.g., AM8191) of the linker reduced hERG activity by more than 30-fold and improved solubility by over 100-fold with minimum loss of antibacterial potency and spectrum.

NBTI AM8085 (5) and enantiomers AM8191 (6) and AM8192 (7) were synthesized via a convergent approach involving three advanced intermediates representing oxabicyclooctane linker, pyridoxazinecarbaldehyde RHS, and 1,5-naphthyridine LHS moieties. They were then assembled in two steps to give final products. The synthesis is presented in Schemes 1–5.

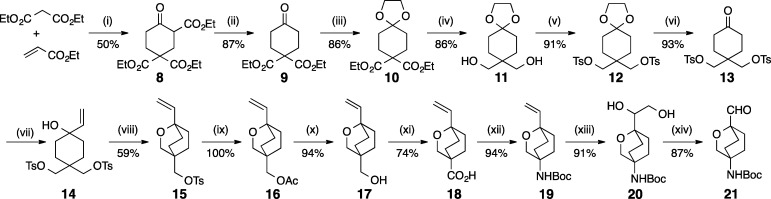

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Linker Moiety.

Reagents: (i) NaH, THF, 40–45 °C; (ii) NaCl, DMSO, H2O, 160 °C; (iii) ethylene glycol, TsOH, toluene, reflux, Dean–Stark; (iv) LiAlH4, Et2O, −20 °C; (v) TsCl, pyridine, 0 °C; (vi) 1 N HCl, THF, reflux; (vii) vinylmagnesium bromide, THF, −78 °C; (viii) NaH, DME, 0 °C; (ix) CsOAc, DMF, 100 °C; (x) K2CO3, MeOH, H2O, RT; (xi) PDC, DMF, 25–40 °C; (xii) (a) DPPA, Et3N, toluene, molecular sieves 4 Å, reflux; (b) t-BuOK, THF; (xiii) OsO4, NMO, t-BuOH, RT; (xiv) NaIO4, THF, RT.

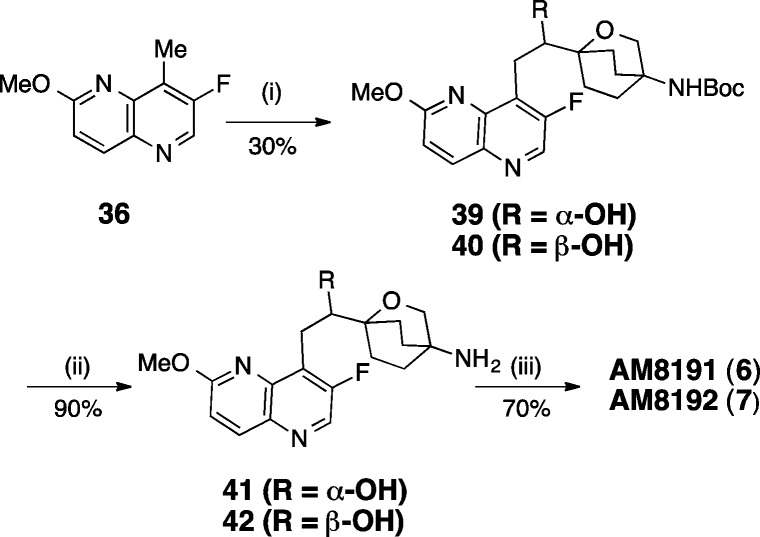

Scheme 5. Synthesis of AM8191 and AM8192.

Reagents: (i) LDA, THF, −78 °C, 21, chiral SFC separation; (ii) TFA, CH2Cl2; (iii) 27, NaBH(OAc)3, DMF, AcOH, 2–6, RT.

The oxabicyclooctane (Scheme 1) linker was synthesized in 14 steps starting with the reaction of diethyl malonate and ethyl acrylate to give triethylcarboxycyclohexanone (8), which was decarboxylated to afford diethylcarboxycyclohexanone (9). The ketone was protected as its cyclic acetal (10), and the ester moieties were then reduced with LiAlH4 to furnish the diol (11) that was subsequently converted to bis tosylate (12). The ketone group of the tosylate was unmasked by reaction with diluted HCl to give 13, which was reacted with vinylmagnesium bromide to provide alcohol 14. Base treatment afforded oxabicyclooctane 15. The tosylate was quantitatively exchanged with acetate to give 16, which was then subjected to base hydrolysis to afford alcohol 17. The primary alcohol was oxidized with PDC to afford carboxylic acid 18. The carboxylic acid was converted to the Boc protected amine (19) by Curtius reaction. The vinyl group was oxidized with osmium tetraoxide to give diol 20, which was cleaved by sodium periodate to give the requisite aldehyde 21.

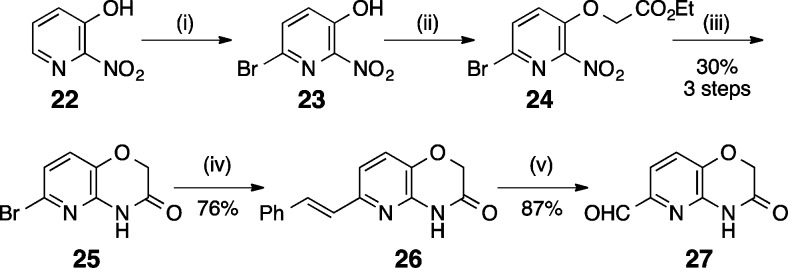

The RHS pyridoxazinecarbaldehyde (Scheme 2) was prepared by bromination of 2-nitro-3-hydroxypyridine (22) to produce 6-bromopyridine 23, which was alkylated to produce ether 24. Reduction of the nitro group at elevated temperatures produced bromo pyridoxazine 25. Suzuki coupling of phenylvinylboronic acid with 25 yielded E-styrene 26, which was ozonolyzed to afford desired aldehyde 27.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of RHS Moiety.

Reagents: (i) MeONa, MeOH, RT, Br2, 0 °C; (ii) K2CO3, ethylbromoacetate, acetone, reflux; (iii) Fe, AcOH, 90 °C; (iv) phenylvinylboronic acid, K2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, water, reflux; (v) O3, CH2Cl2, MeOH, −78 °C.

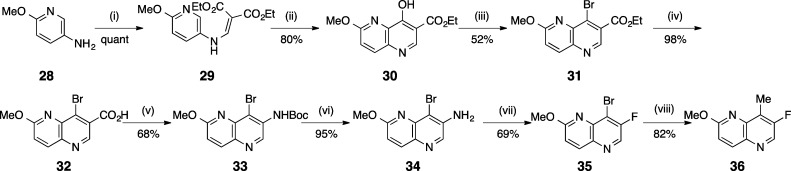

The synthesis of the LHS 1,5-naphthyridine moiety began by reaction of ethoxymethyl malonate with 2-methoxy-5-amino-pyridine (28) to afford 29 (Scheme 3). Heating of 29 in diphenyl ether produced 8-hydroxy-1,5-naphthyridine 30. Reaction of 30 with PBr3 afforded bromide 31, which was hydrolyzed in the presence of base to give the acid 32. Curtius rearrangement of the acid afforded Boc-protected amine 33. Boc deprotection afforded the free amine 34, which was converted to 35 by reaction with nitrosonium tetrafluoroborate. Cross-coupling of 35 with methylboronic acid produced the final LHS intermediate 36.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of LHS Moiety.

Reagents: (i) ethoxymethylmalonate, EtOH, reflux; (ii) Ph2O, 260 °C; (iii) PBr3, DMF; (iv) NaOH, THF, RT; (v) DPPA, Et3N, t-BuOH, DMF, 100 °C; (vi) TFA, CH2Cl2, −10 °C; (vii) NOBF4, THF, −10 °C-RT; (viii) methylboronic acid, (Ph3P)4Pd, K2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C.

Hydroboration of vinyl oxabicyclooctane 19 followed by Suzuki coupling with 8-bromo-1,5-naphthyridine (35) led to 37 (Scheme 4). Boc-deprotection followed by reductive amination of 38 using pyridoxazinecarbaldehyde 27 afforded AM8085 (5), which was converted to the corresponding hydrochloride salt by treatment with HCl in dioxane.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of AM8085.

Reagents: (i) 9-BBN, THF; (ii) 35, Pd(PPh3)4, K3PO4, EtOH/H2O; (iii) TFA, CH2Cl2; (iv) 27, NaBH(OAc)3, DMF, AcOH, 2–6, RT.

Aldol reaction of 36 with aldehyde 21 afforded an enantiomeric mixture of alcohols 39 and 40 (Scheme 5). Chiral SFC separation provided enantiomerically pure 39 (faster eluting) and 40. The absolute configuration of the chiral center was elucidated independently by calculated and experimental vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) and Mosher methods. The Boc-group of the two pure enantiomers 39 (2S) and 40 (2R) were deprotected separately to give amines 41 and 42, which were reductively aminated with aldehyde 27 to afford AM8191 (6) and AM8192 (7), respectively.

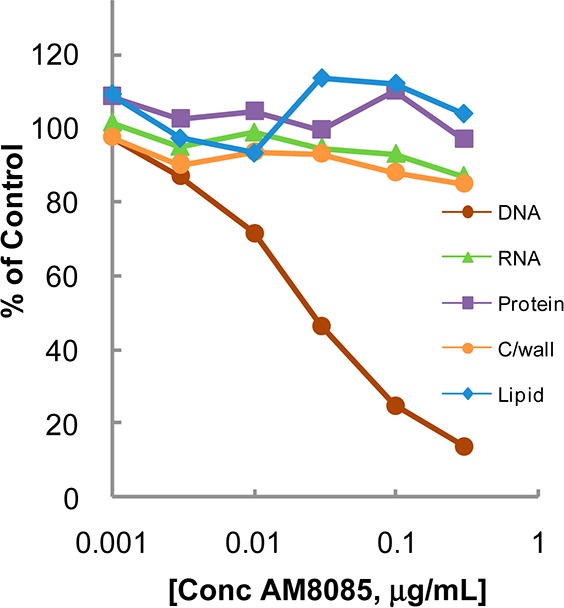

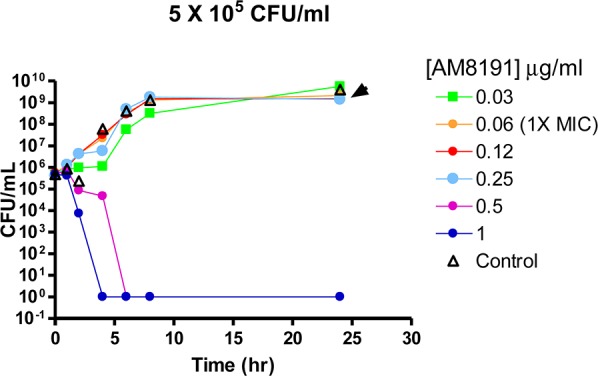

The hydrochloride salts of oxabicyclooctane-linked NBTIs 5–7 showed broad-spectrum antibacterial activities (Table 1) against most ESKAPE pathogens, as well as MRSA and Gram-negative pathogens, A. baumannii and E. coli. They showed weaker activities against P. aeruginosa. AM8191, the S enantiomer at C-2 of the linker was slightly more potent than the R enantiomer AM8192. These compounds retained activity against quinolone-resistant strains of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. S. aureus MIC values were not significantly altered in the presence of 50% human serum or sheared DNA (500 μg/mL) indicating that they did not bind significantly to serum or DNA. AM8085 and AM8191 showed potent activity against S. aureus and E. coli gyrase with IC50 values of 1.0 μM or less. Both compounds showed better activity against E. coli topo IV (IC50 0.2 and 0.5 μM) compared to S. aureus topo IV (4.4 and 10.4 μM) when compared to respective gyrase IC50s (Table 1). Macromolecular labeling studies demonstrated that AM8085 selectively inhibited DNA synthesis over RNA, protein, cell wall, and lipid (Figure 1).17 AM8191 exhibited >3 log10 reduction of colony forming units (CFU) of S. aureus in an in vitro time kill kinetic experiment (>105 CFU/mL inoculum) at >4× of MIC (0.06–0.12 μg/mL) confirming bactericidal effect of this compound (Figure 2).

Table 1. Antibacterial, Gyrase, and hERG Activities of NBTIsa.

| AM8085 | AM8191 | AM8192 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | MIC, μg/mL | ||

| S. aureus MSSA | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| S. aureus MRSA | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| S. pneumoniae | 0.064 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| E. faecalis | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| E. faecium VRE | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 |

| H. influenzae | 1 | 0.5 | NT |

| E. coli | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| A. baumannii | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| M. catarrhalis | NT | 0.015 | NT |

| P. aeruginosa | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| S. aureus quinSb | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| S. aureus quinRb | 0.064 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Bacterial Enzymes | IC50, μM | ||

| S. aureus gyrase | 0.22 | 1.02 | NT |

| S. aureus topo IV | 4.4 | 10.4 | NT |

| E. coli gyrase | 0.18 | 0.78 | NT |

| E. coli topo IV | 0.2 | 0.5 | NT |

| Off target | IC50, μM | ||

| hERG patch express (CHO cell) | 0.6 | 18 | NT |

Linezolid and levofloxacin were used as controls for the MIC measurements using the micro broth dilution or agar based methods, which yielded the MIC ranges reported by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI M7-A8). AM8191 and AM8192 did not show any alteration of the S. aureus MIC in the presence of 50% human serum or 500 μg/mL DNA. AM8085 showed a 4- and 2-fold increase in the MIC under the same test conditions, respectively. NT indicates not tested.

For comparison, the MIC values of levofloxacin was >64-fold higher with the quinolone resistant (quinR) as compared to the sensitive (quinS) strain, (>16 vs 0.25 μg/mL).

Figure 1.

Macromolecular synthesis inhibition of AM8085 in S. aureus.

Figure 2.

Time kill kinetics of AM8191 in S. aureus. The MIC in the experiment was 0.06–0.12 μg/mL.

Significant attenuation of undesirable hERG activity is critical to the future development of these compounds as antibacterial agents. We evaluated hERG activity in a functional automated patch clamp assay (see Supporting Information for Methods). In this assay, AM8085 showed an IC50 of 0.6 μM. The 2S-hydroxy group of AM8191 improved the polarity and attenuated the hERG activity (IC50 = 18 μM). However, more than an order of magnitude attenuation of hERG activity may be required for a clinical development compound.

AM8191 HCl salt showed excellent (>50 mg/mL) solubilities in various acceptable intravenous and oral vehicles. It showed PBS solubility of ∼154 μM (pH 7) and ∼200 μM (pH 2), whereas AM8085 showed significantly lower PBS solubility of <0.89 μM (pH 7) and 20.3 μM (pH 2). AM8191 and AM8192 showed >25% free fractions in human, dog, or mouse plasma, whereas corresponding free fractions for AM8085 were less than 2%. All three compounds showed good (30–60 min) stability in human, mouse, and dog liver microsomal incubations. To assess for in vivo efficacy, all compounds were evaluated in a S. aureus murine survival model of bacteremia. In this model, AM8085 showed ED50 values of 5.5 mg/kg by intravenous (i.v.) dosing and 17 mg/kg by oral (p.o.) dosing. AM8191 showed ED50 values of 2.5 mg/kg (i.v.) and 2.2 mg/kg (p.o.). AM8192 showed good in vivo efficacy as well in this model, providing ED50 values of 3.5 mg/kg (i.v.) and 4.5 mg/kg (p.o.). AM8191 also showed efficacy in a similar E. coli murine survival model exhibiting ED50 values of 23 mg/kg (i.v.) and 85 mg/kg (p.o.). Mouse PK data (Table 2) generally supported the observed efficacy.

Table 2. Mouse and Dog Pharmacokinetics Parameters of NBTIs.

| AM8085 | AM8191 | AM8192 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mousea | |||

| AUCn (μM·h/mpk) | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| Clp (mL/min/kg) | 34.6 | 43.3 | 48.7 |

| Vdss (L/kg) | 2.22 | 1.61 | 4.94 |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.24 | 1.70 | 2.15 |

| %F | 71.6 | 30.1 | 25.3 |

| Dogb | |||

| AUCn (μM·h/mpk) | 0.43 | 3.57 | NT |

| Clp (mL/min/kg) | 39.8 | 9.16 | NT |

| Vdss (L/kg) | 5.36 | 2.60 | NT |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.85 | 4.49 | NT |

| %F | >100 | 40.4 | NT |

C57BL/6 mouse (n = 2) dosed at 1 mg/kg (i.v.) and 2 mg/kg (p.o.).

Beagle dog (n = 2) dosed at 1 mg/kg (i.v.) and 2 mg/kg (p.o.).

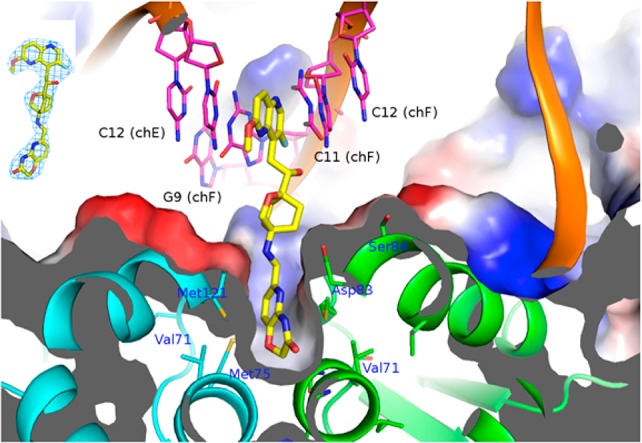

AM8191 was cocrystallized with the DNA–gyrase complex (Figure 3) in a manner similar to that reported by Bax et al.5 The binding mode of AM8191 resembles that of GSK299423.5 The 1,5-naphthyridine (LHS) ring binds between the two central base pairs of the stretched DNA through van der Waals interactions between the DNA base pairs and the aromatic 1,5-naphthyridine ring. The pyridoxazine (RHS) moiety penetrates into the hydrophobic pocket between the two gyrase A subunits at the bottom portion of the complex. van der Waals interactions of Ala68, Val 71, Met75, and Met121 with the pyridine ring further stabilize the ternary complex. The linker moiety of AM8191 is located in the donut-hole and generally exposed to solvent other than the position-7 basic amine, which showed a polar interaction with the Asp83 side chain and accounts at least partially for the high affinity of the compound. No interaction partners were identified for the hydroxyl group at C-2 of the linker, indicative of no direct binding contribution. This finding is consistent with the observation that the two enantiomers demonstrated identical biological activity.

Figure 3.

The 2.7 Å cocrystal structure of AM8191 bound to a DNA–gyrase complex. Gyrases A and B are shown in green and cyan. AM8191 is colored in yellow and DNA duplex in magenta. Upper left: the electron density map of AM8191.

In summary, this letter describes the discovery, synthesis, and characterization of new NBTIs with an oxabicyclooctane linker and attenuated hERG activity with potent broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, including efficacy in mouse models of S. aureus and E. coli infections. Hydroxylation of the linker chain provided compounds with improved physical properties leading to improved oral efficacy. X-ray crystallographic studies provided binding insights consistent with amino-piperidine linked NBTIs.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge technical assistance from WuXi chemistry, DMPK, and pharmaceutical sciences teams. The authors thank Drs. Chris Pillar and Dean Shinabarger of Micromyx for providing a portion of the MIC, MML, and Kill kinetics data.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures of synthesis of 5–42, Mosher ester analysis, materials and methods for MIC, systemic infection model, and hERG assay. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

⊥ (S.B.S.) Pharma Consulting, Edison, New Jersey 08820, United States.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Klevens R. M.; Morrison M. A.; Nadle J.; Petit S.; Gershman K.; Ray S.; Harrison L. H.; Lynfield R.; Dumyati G.; Townes J. M.; Craig A. S.; Zell E. R.; Fosheim G. E.; McDougal L. K.; Carey R. B.; Fridkin S. K. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhanel G. G.; DeCorby M.; Adam H.; Mulvey M. R.; McCracken M.; Lagace-Wiens P.; Nichol K. A.; Wierzbowski A.; Baudry P. J.; Tailor F.; Karlowsky J. A.; Walkty A.; Schweizer F.; Johnson J.; Hoban D. J. Prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in Canadian hospitals: results of the Canadian Ward Surveillance Study (CANWARD 2008). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4684–4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisacchi G. J.; Dumas J. Recent advances in the inhibition of bacterial type II topoisomerases. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C.; Janin Y. L. Non-quinolone inhibitors of bacterial type IIA topoisomerases: a feat of bioisosterism. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2313–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax B. D.; Chan P. F.; Eggleston D. S.; Fosberry A.; Gentry D. R.; Gorrec F.; Giordano I.; Hann M. M.; Hennessy A.; Hibbs M.; Huang J.; Jones E.; Jones J.; Brown K. K.; Lewis C. J.; May E. W.; Saunders M. R.; Singh O.; Spitzfaden C. E.; Shen C.; Shillings A.; Theobald A. J.; Wohlkonig A.; Pearson N. D.; Gwynn M. N. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature 2010, 466, 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener J. J.; Gomez L.; Venkatesan H.; Santillan A. Jr.; Allison B. D.; Schwarz K. L.; Shinde S.; Tang L.; Hack M. D.; Morrow B. J.; Motley S. T.; Goldschmidt R. M.; Shaw K. J.; Jones T. K.; Grice C. A. Tetrahydroindazole inhibitors of bacterial type II topoisomerases. Part 2: SAR development and potency against multidrug-resistant strains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2718–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. T.; Stachyra T.; Platel D.; Girard A. M.; Claudon M.; Bruneau J. M.; Miossec C. Mechanism of action of the antibiotic NXL101, a novel nonfluoroquinolone inhibitor of bacterial type II topoisomerases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3339–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. T.; Coleman K. New inhibitors of bacterial topoisomerase GyrA/ParC subunits. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2009, 10, 804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L.; Hack M. D.; Wu J.; Wiener J. J.; Venkatesan H.; Santillan A. Jr.; Pippel D. J.; Mani N.; Morrow B. J.; Motley S. T.; Shaw K. J.; Wolin R.; Grice C. A.; Jones T. K. Novel pyrazole derivatives as potent inhibitors of type II topoisomerases. Part 1: synthesis and preliminary SAR analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2723–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles T. J.; Axten J. M.; Barfoot C.; Brooks G.; Brown P.; Chen D.; Dabbs S.; Davies D. T.; Downie D. L.; Eyrisch S.; Gallagher T.; Giordano I.; Gwynn M. N.; Hennessy A.; Hoover J.; Huang J.; Jones G.; Markwell R.; Miller W. H.; Minthorn E. A.; Rittenhouse S.; Seefeld M.; Pearson N. Novel amino-piperidines as potent antibacterials targeting bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 7489–7495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles T. J.; Barfoot C.; Brooks G.; Brown P.; Chen D.; Dabbs S.; Davies D. T.; Downie D. L.; Eyrisch S.; Giordano I.; Gwynn M. N.; Hennessy A.; Hoover J.; Huang J.; Jones G.; Markwell R.; Rittenhouse S.; Xiang H.; Pearson N. Novel cyclohexyl-amides as potent antibacterials targeting bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 7483–7488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton-Fry M. J.; Brickner S. J.; Hamel J. C.; Brennan L.; Casavant J. M.; Chen M.; Chen T.; Ding X.; Driscoll J.; Hardink J.; Hoang T.; Hua E.; Huband M. D.; Maloney M.; Marfat A.; McCurdy S. P.; McLeod D.; Plotkin M.; Reilly U.; Robinson S.; Schafer J.; Shepard R. M.; Smith J. F.; Stone G. G.; Subramanyam C.; Yoon K.; Yuan W.; Zaniewski R. P.; Zook C. Novel quinoline derivatives as inhibitors of bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 2955–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles T. J.; Hennessy A. J.; Bax B.; Brooks G.; Brown B. S.; Brown P.; Cailleau N.; Chen D.; Dabbs S.; Davies D. T.; Esken J. M.; Giordano I.; Hoover J. L.; Huang J.; Jones G. E.; Sukmar S. K.; Spitzfaden C.; Markwell R. E.; Minthorn E. A.; Rittenhouse S.; Gwynn M. N.; Pearson N. D. Novel hydroxyl tricyclics (e.g., GSK966587) as potent inhibitors of bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5437–5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck F.; Alm R.; Brassil P.; Newman J.; Dejonge B.; Eyermann C. J.; Breault G.; Breen J.; Comita-Prevoir J.; Cronin M.; Davis H.; Ehmann D.; Galullo V.; Geng B.; Grebe T.; Morningstar M.; Walker P.; Hayter B.; Fisher S. Novel N-linked aminopiperidine inhibitors of bacterial topoisomerase type II: broad-spectrum antibacterial agents with reduced hERG activity. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7834–7847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck F.; Alm R. A.; Brassil P.; Newman J. V.; Ciaccio P.; McNulty J.; Barthlow H.; Goteti K.; Breen J.; Comita-Prevoir J.; Cronin M.; Ehmann D. E.; Geng B.; Godfrey A. A.; Fisher S. L. Novel N-linked aminopiperidine inhibitors of bacterial topoisomerase type II with reduced pKa: antibacterial agents with an improved safety profile. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 6916–6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surivet J. P.; Zumbrunn C.; Rueedi G.; Hubschwerlen C.; Bur D.; Bruyere T.; Locher H.; Ritz D.; Keck W.; Seiler P.; Kohl C.; Gauvin J. C.; Mirre A.; Kaegi V.; Dos Santos M.; Gaertner M.; Delers J.; Enderlin-Paput M.; Boehme M. Design, synthesis, and characterization of novel tetrahydropyran-based bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors with potent anti-gram-positive activity. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7396–7415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. W.; Goetz M. A.; Smith S. K.; Zink D. L.; Polishook J.; Onishi R.; Salowe S.; Wiltsie J.; Allocco J.; Sigmund J.; Dorso K.; Lee S.; Skwish S.; de la Cruz M.; Martin J.; Vicente F.; Genilloud O.; Lu J.; Painter R. E.; Young K.; Overbye K.; Donald R. G.; Singh S. B. Discovery of kibdelomycin, a potent new class of bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitor by chemical-genetic profiling in Staphylococcus aureus. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 955–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.