Abstract

Several natural products derived from entomopathogenic fungi have been shown to initiate neuronal differentiation in the rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line. After the successful completion of the total synthesis program, the reduction of structural complexity while retaining biological activity was targeted. In this study, farinosone C served as a lead structure and inspired the preparation of small molecules with reduced complexity, of which several were able to induce neurite outgrowth. This allowed for the elaboration of a detailed structure–activity relationship. Investigations on the mode of action utilizing a computational similarity ensemble approach suggested the involvement of the endocannabinoid system as potential target for our analogs and also led to the discovery of four potent new endocannabinoid transport inhibitors.

Keywords: Neurite outgrowth, natural products, endocannabinoid membrane transport, CB1 receptor, SAR, truncated

Neurodegenerative disorders are among the leading causes of death in aging societies, and every third person dying suffers from a type of dementia. To date, approved medication slows down the progress or reduces the symptoms of dementia.1 Consequently, neurite-growth-promoting and neuroprotective compounds are considered as molecular approaches for the restoration of brain function.2,3 Several natural products have been reported to induce neurite outgrowth, such as withanolide A,4−6 the gentiside family,7,8 gelsemiol9,10 or jiadifenolide.11 Often, the structural complexity of natural products is directly associated with their challenging and time-consuming synthesis.12−14 Therefore, structural simplification while maintaining or even increasing their respective bioactivity has emerged as an important strategy in natural products research (“reduce to the maximum”)15 and is crucial to facilitate the supply of beneficial small molecules. Wender introduced the concept of function-orientated synthesis, which is based on the reduction of molecular complexity by retained function (bioactivity), resulting in increased step economy.16 Truncation of complex natural products as exemplified by the modification of halichondrin B resulted in a drug in clinical use.17,18 In the area of neuritogenic natural products, we19 and others20 have recently provided functionally optimized scaffolds for neuronal differentiation.

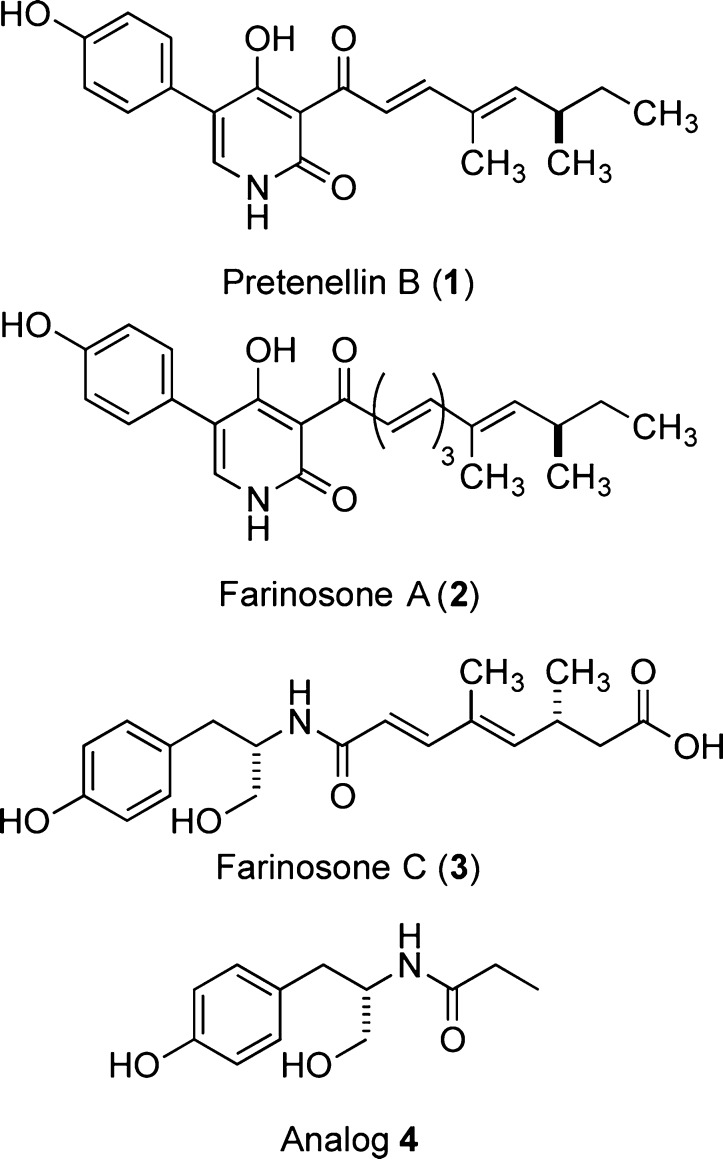

Our group accomplished the total synthesis of several neuritogenic alkaloids originating from entomopathogenic fungi such as pretenellin (1), farinosone A (2), or farinosone C (3) and assigned their absolute configuration (Figure 1).9,10,21−23 While the biosynthesis of these compounds is likely to be related,24,25 their synthesis required at least 14 steps.22 From a very limited structure–activity relationship study (SAR), we learned that the much simpler l-tyrosinol-propionamide 4 was able to induce neuronal differentiation, albeit at higher concentration than the parent analog 3.22 We therefore aimed to synthesize structurally optimized derivatives of farinosone C (3), which retain or even display more potent neurite outgrowth inducing capability. At the same time, this endeavor would also result in a more defined description of the pharmacophore. In this communication, we report the results of this SAR study on farinosone C (3) analogs and perform preliminary studies on the mechanism of action, identifying the modulation of the endocannabinoid system as a potential target pathway.

Figure 1.

Neuritogenic natural products and first analog 4.

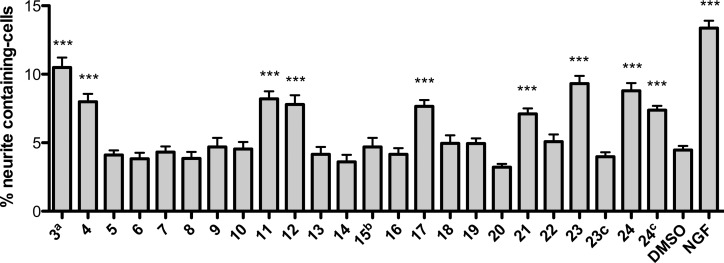

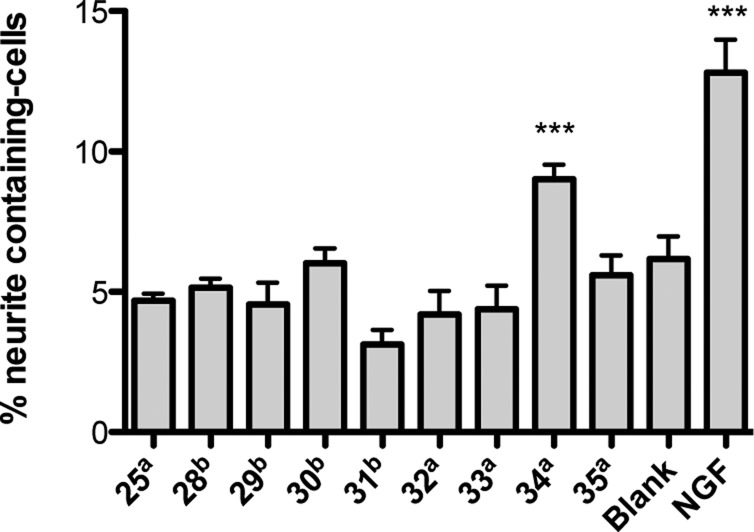

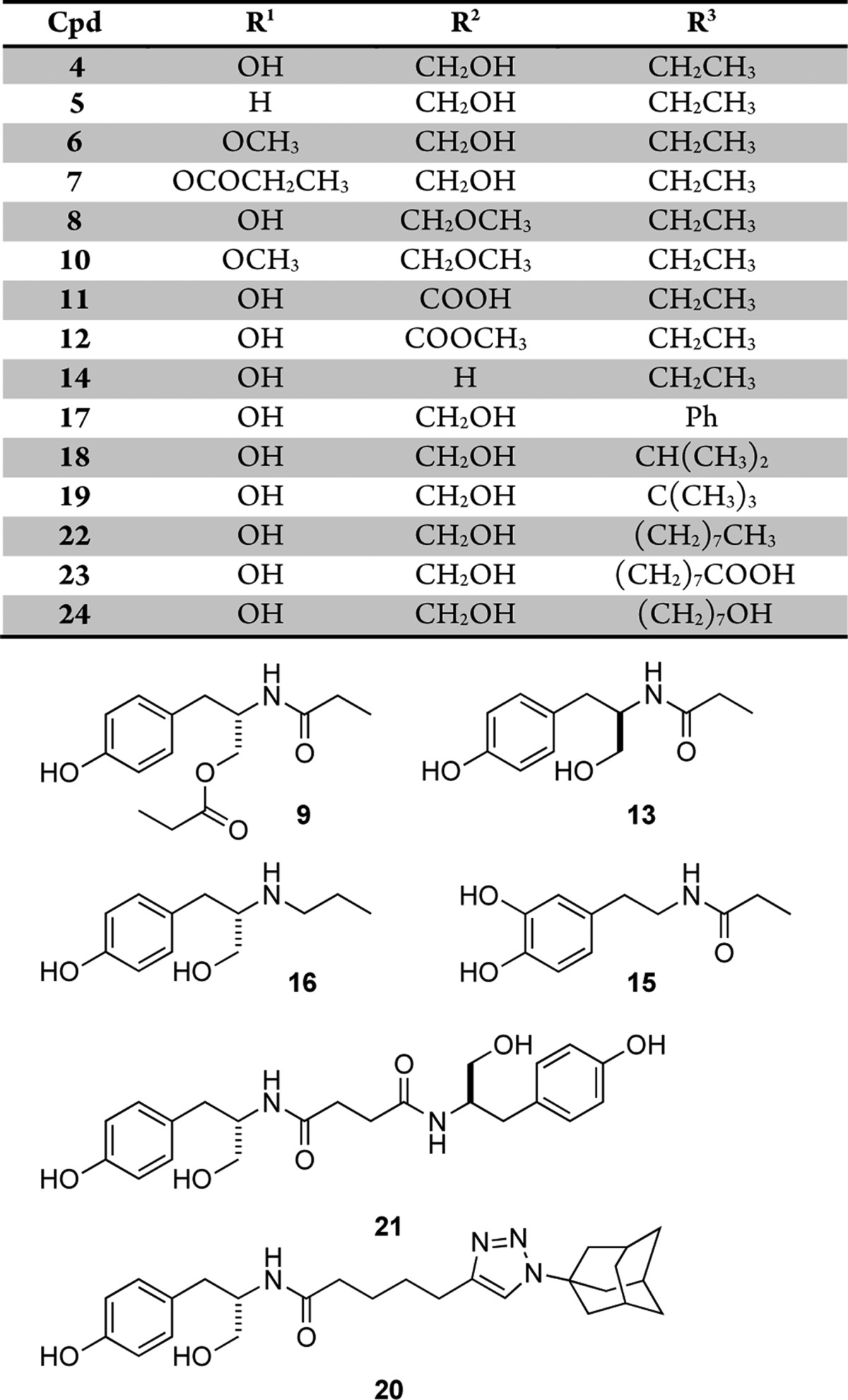

We prepared a collection of farinosone C (3) derivatives (Table 1; for details see Supporting Information) and profiled their neuritogenic properties (Figure 2) using a modified procedure of the well established PC12 cell assay that can serve as a simplified model system for NGF-mediated, neuronal differentiation.21,22,26−28 First, the role of the phenolic OH group was evaluated. Since phenols are known to be easily oxidized in an enzymatic environment,29 we envisioned that the removal (→ 5), methylation (→ 6), or esterification (→ 7) of the hydroxyl group might be beneficial for metabolic stability. However, all these modifications led to a complete loss of bioactivity, which suggested that this functional group is essential for activity. The role of the primary hydroxyl group was investigated next. Again, methylation and esterification were not tolerated, as the corresponding compounds 8 and 9 were found to be inactive, as was the doubly methylated compound 10. Interestingly, however, oxidation to the carboxylic acid 11 and derivatization to its methyl ester analog 12 led to biologically active compounds. We then investigated the influence of the stereogenic center: formation of the d-tyrosinol-propionamide 13 or complete removal of the CH2OH side chain in 14 resulted in inactivity, showing that the presence of the hydroxymethylene moiety in the (S)-configuration is mandatory for neuritogenic activity in the PC12 cell assay. The close catechol analog of 14, dopaminyl propanoate (15), caused cytotoxicity at our standard concentration of 50 μM and was inactive at 5 μM. The amide moiety was also shown to be essential, as the secondary amine 16 was inactive. Modifications of the amide only tolerated a planar aromatic substituent (→ 17); the more bulky isobutyramide 18 and pivalamide analogs 19 displayed no significant activity. With these results in hand, we turned our attention toward the alkyl chain, the part of farinosone C (3) that has synthetically been the most demanding. The very bulky triazole-adamantyl derivative 20 was not active; however, the dimer 21 of l-tyrosinol-propionamide 4 showed significant bioactivity. Finally, we were interested in the role of the acidic terminus of farinosone C (3). It appears that a polar terminus is required for the long chain aliphatic compounds, as the apolar amide 22 revealed no activity. Terminal acid 23 and the terminal alcohol 24 showed good activity; the latter compound was even able to induce cell differentiation at 10 μM concentration, thus rendering the triol 24 an even more potent compound than the parent natural product farinosone C (3, Figure 3). This interesting result demonstrated that the synthetically challenging side chain of the parent natural product can be replaced by an unbranched and fully saturated alkyl chain.

Table 1. Synthesized Farinosone C Analogs 4–24.

Figure 2.

Neuritogenic activity of farinosone C (3) and its simplified analogs (4–24) in the PC12 assay. All values were determined at 50 μM, except the following: a, 20 μM; b, 5 μM; c, 10 μM. Positive control: nerve growth factor (NGF), 20 ng mL–1. Solvent control: DMSO (0.1%). Incubation period: 2 days. Values are reported as mean (unpaired t test; confidence interval 95%; significance: *** = P < 0.0001, n = 3, mean ± SEM).

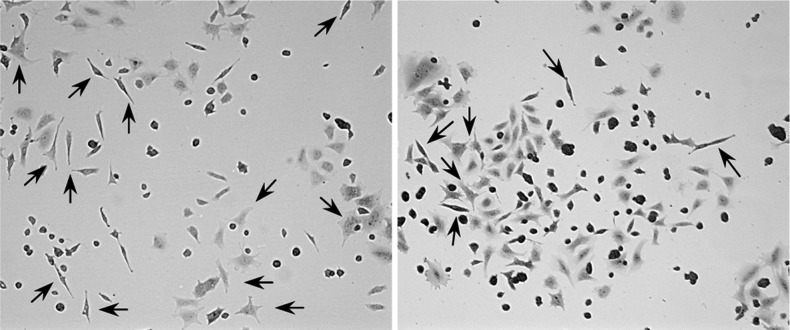

Figure 3.

Representative images of differentiated PC12 cells: left, 24, 10 μM; right, DMSO vehicle control. Arrows indicate differentiated PC12 cells.

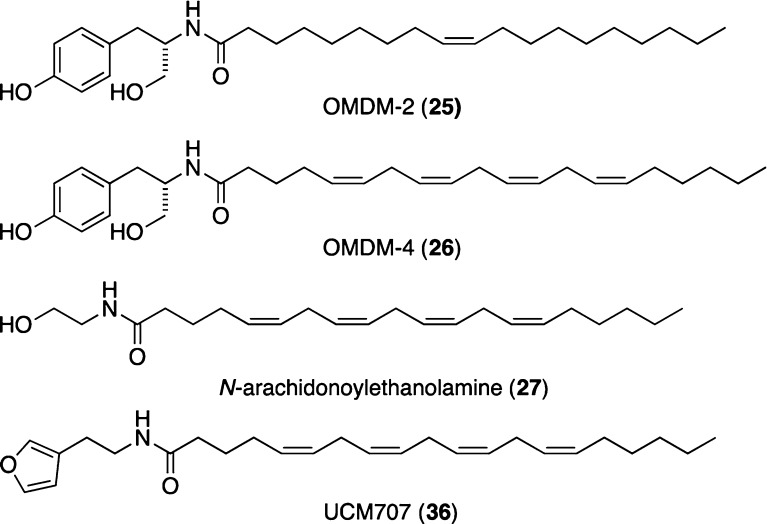

Many natural products with neuritogenic or neuritotrophic properties have been reported.4−11 However, the underlying biological pathways involved in neuronal cell differentiation, which are influenced by such compounds, are only partially understood. We therefore decided to investigate the molecular targets of the synthetic derivatives prepared that display neuritogenic properties. Computational approaches by structural similarity searching30 hinted at fatty acid amides such as OMDM-2 (25) and OMDM-4 (26), which bind to the cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the low micromolar range. These compounds serve as aromatic structural analogs for the endogenous cannabinoid N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) 27 (Figure 4).31−33

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of the endocannabinoid AEA (27), two endocannabinoid-like CB1 ligands (25 and 26) and the endocannabinoid transport inhibitor UCM707 (36).

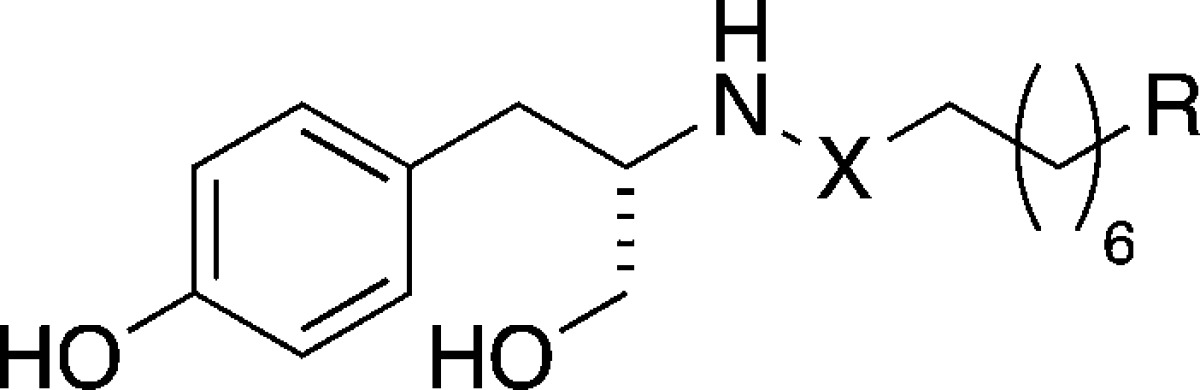

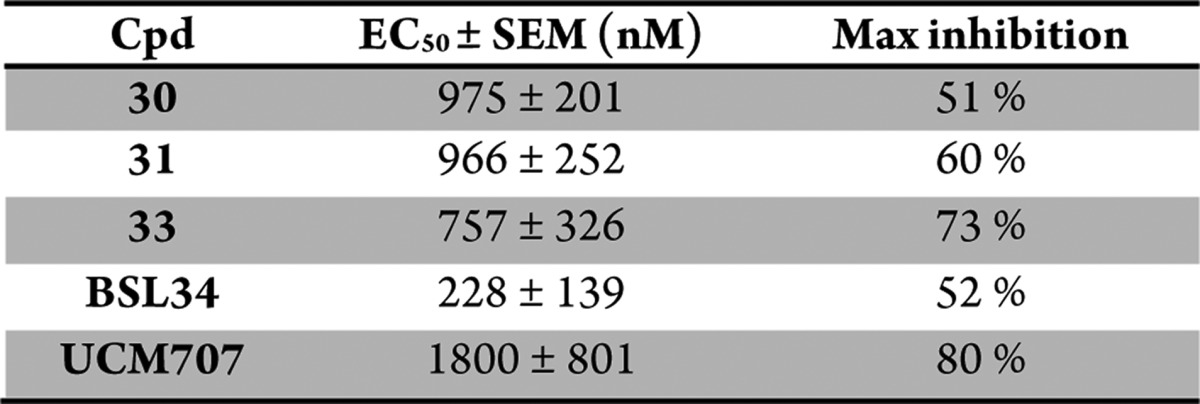

Figadère and co-workers demonstrated that fatty acid amide derivatives of tryptamine are also able to induce neuronal differentiation.34 Activation of the CB1 receptor was reported to induce neuronal differentiation through a complex signaling network in Neuro-2A cells35,36 and to restore the neurite outgrowth in hyperglycemic PC12 cells.37 Based on these structural precedents for both CB1 binding and its role as neuritogenic target, we prepared a second collection of compounds (Table 2) by structurally expanding the heptamethylene scaffold of compounds 22–24 to obtain longer alkyl chains with no or partial unsaturation.

Table 2. Fatty Acid Amide Derived Analogs 28–35.

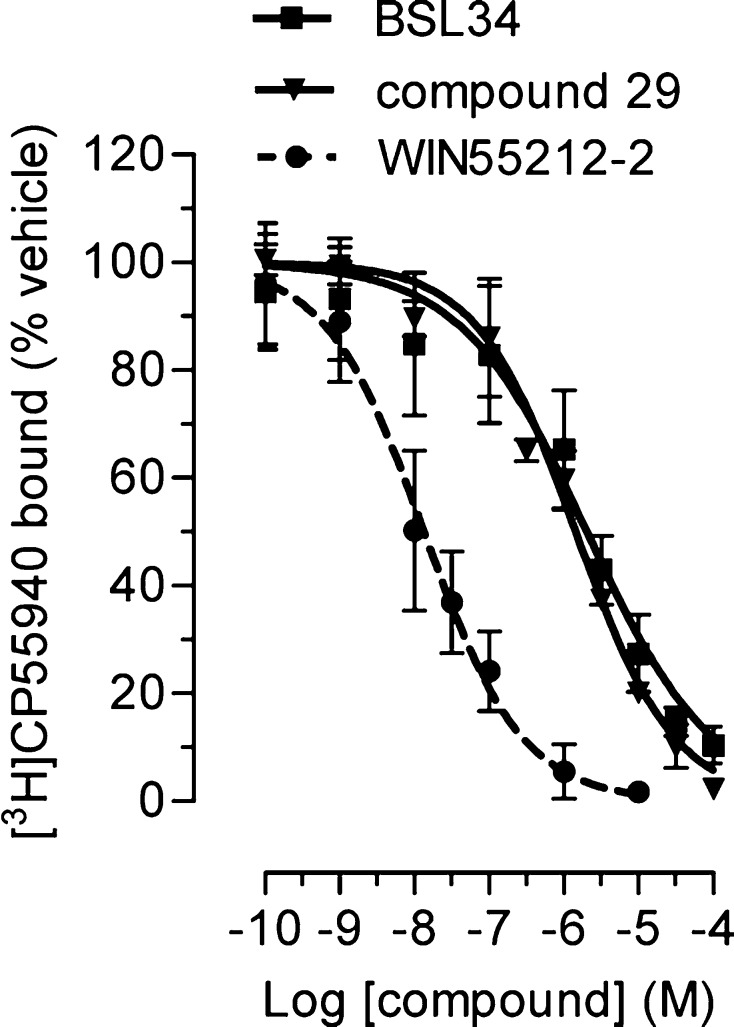

Compounds 28–35 and OMDM-2 (25) were first screened for neurite outgrowth at 10 μM concentration. We noticed that all compounds bearing a secondary amine function (28–31) were not tolerated by PC12 cells, as they induced cytotoxicity. After reduction of the concentration by one order of magnitude, neither toxicity nor neuritogenic activity could be observed for these amines (Figure 5). Among the amide bearing amphiphiles (25, 32–35), only 34 (hereafter referred as BSL34) showed a significant activity at 10 μM (Figure 5), which suggests that the degree of unsaturation of the alkyl chain plays a crucial role. Also the length of the alkyl chain is of importance; 24 has been identified as the most potent compound, whereas triol amide 33 is inactive. Interestingly, they only differ in the length of the alkyl chain (C7 versus C14).

Figure 5.

Neuritogenic activity of OMDM-2 (25) and fatty acid derived analogs. Values were determined at a: 10 μM, b: 1 μM, NGF control: 20 ng mL–1. DMSO control: 0.1%. Incubation period: 2 days. Values are reported as means ± SEM (Unpaired t test, confidence interval 95%, significance: *** = P < 0.0001, n = 3).

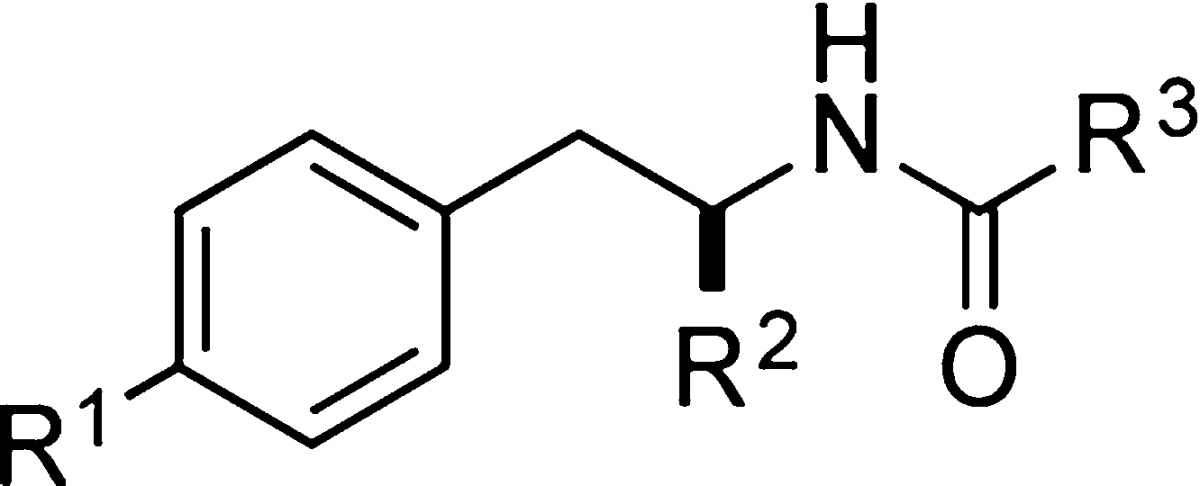

Next, we investigated the binding affinities for the compounds at CB receptors using membrane preparations from CHO cells stably transfected with human CB receptors. Most of the compounds showed weak binding to CB1 and CB2 receptors at the screening concentration of 1 μM (Supporting Information Figure 1A and 1B). Nonetheless, we noticed that 29 and, more importantly, the neuritogenic omega-6 fatty acid amide derivative BSL34 selectively bind to the CB1 receptor with moderate potency (Ki values of 530 and 810 nM, respectively (Figure 6)).

Figure 6.

CB1 binding properties of compounds 29 and BSL34. The assay was performed as described before38 by incubating for 90 min at 30 °C CHO-hCB1 membranes with different concentrations of tested compounds (or the positive control, WIN55,212-2) in the presence of 0.5 nM [3H]-CP55940 (mean ± SD; n = 2–3).

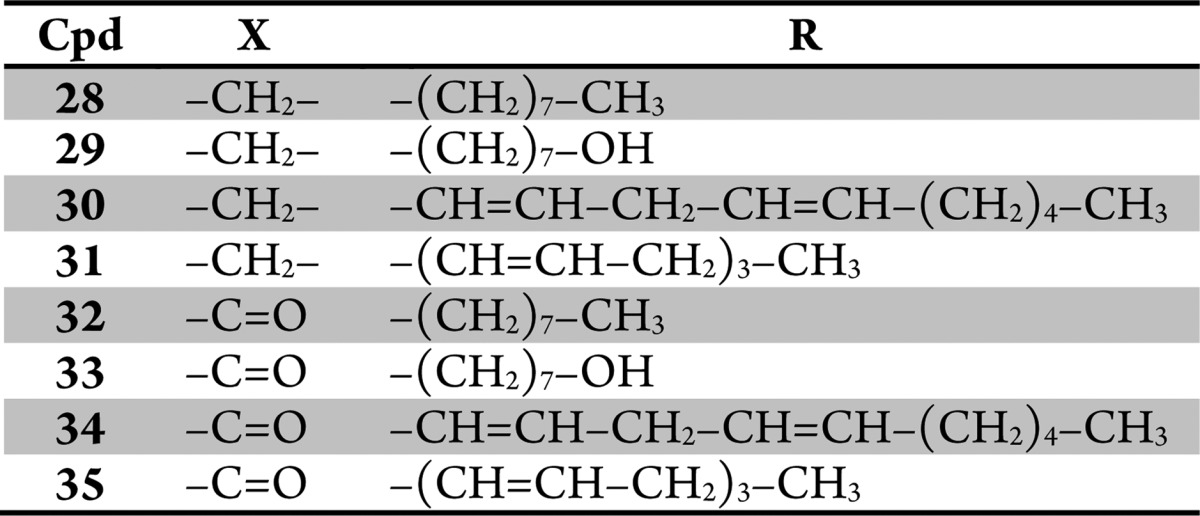

To further clarify the role of the CB1 receptor in our system, we incubated PC12 cells with the CB1 selective agonist O-689 at 100 nM and with two CB1 antagonists, rimonabant (1 μM and 100 nM) and AM251 (3 μM and 100 nM).39,40 Despite multiple attempts under manifold conditions, neuronal differentiation could not be achieved by O-689 treatment nor were the selective CB1 antagonists able to suppress the BSL34-induced neuronal differentiation, suggesting that CB1 is not directly involved in our PC12 neurite outgrowth assay. The endocannabinoid system included several proteins involved in the biosynthesis, degradation, and trafficking of the two main endogenous ligands of CB receptors, AEA (27), and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG). Intra- and extracellular levels of 2-AG and AEA (27) are under control of degrading enzymes, intracellular carriers, and the putative endocannabinoid membrane transporter (EMT). Modulation of those targets’ function leads to a change in the levels of AEA (27) and 2-AG, thus raising indirect CB receptor activation.41 We have therefore evaluated the impact of our compounds on the activity of those targets. Most of the compounds tested at 1 μM showed a weak inhibition (20–25%) of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the main enzyme involved in AEA hydrolysis (Supporting Information Figure 2). The main enzymes involved in 2-AG hydrolysis (monoacylglycerol lipase, MAGL, α,β-hydrolase-6 and -12, ABHD-6 and -12) were not significantly inhibited at the same concentration (Supporting Information Figure 3A and 3B). AEA analogs (28–35) could also modulate the trafficking of endocannabinoids across the plasma membrane. Gratifyingly, this hypothesis was corroborated by the discovery of four fatty acid amides as excellent EMT inhibitors. Four of the tested compounds inhibited AEA (27) cellular uptake with submicromolar EC50 values. The most potent compound, BSL34, inhibited the EMT activity with one order of magnitude more than UCM707 (36), a commercially available benchmark inhibitor (Table 3 and Supporting Information Figure 4).41−43

Table 3. [3H]AEA transport inhibition parameters. EC50 values and maximal effect were determined from concentration-dependent curves performed in U937 human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cells as previously described (n = 3-5).41.

With the synthesized collection of farinosone C analogs reported herein, we were able to elucidate the structure requirements for activity derived from the parent natural product 3. It was demonstrated, for example, that the branched and unsatured side chain can by simplified or truncated. The phenolic hydroxyl group allowed no alteration, but the primary one did to some extent. This SAR study unearthed seven neuritogenic molecules (10, 11, 17, 21, 23, 24, BSL34), of which two, the triol 24 and the fatty acid derivative BSL34, possessed a superior neurotrophin-like function than the natural product 3 itself, with a much reduced molecular complexity. Both can be obtained from cheap commercial starting materials in one step, and supply is therefore ensured. Our data also suggest the involvement of the endocannabinoid system in neuronal differentiation induced by these classes of compounds. The previously reported44 CB1 receptor-induced neuritogenic effect was not reproduced in our hands, as the selective agonist O-689 did not lead to any significant neuronal differentiation and the BSL34-induced effect was not blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonists AM251 or rimonabant. The experimental conditions of the PC12 assay have a significant impact on the read-out. Indeed, HU-210 was shown to restore the neurite outgrowth in hyperglycemic cells to a degree comparable with normal cells in a CB1 receptor-dependent mechanism, while contrasting data were reported for normoglycemic cells. CB1 receptor activation was shown either to trigger44 or to impair neurite outgrowth.45 In addition, different studies describe a variable CB1 receptor expression in PC12 cells. The receptor was either found37 or not found46,47 on the plasma membrane of undifferentiated PC12 cells. Others reported CB1 receptor expression only in NGF-differentiated PC12 cells.45 Possible reasons for apparent discrepancies between these and our findings might relate to the relative expression level of CB1 receptors and thus point toward a CB1 receptor-independent effect. However, as BSL34 showed a potent EMT inhibition, we assume that the resulting changes in the local concentration of endocannabinoids, for example, AEA and 2-AG, could affect cell differentiation. EMT is involved in the bidirectional trafficking of endocannabinoids across the plasma membrane,41 and its inhibition leads to a different compartmentalization of AEA (27) and 2-AG. AEA (27) has several other targets beyond the plasma membrane located CB1/2 receptors, such as TRPV1 channels, intracellular CB1 receptors, and nuclear PPARs. Some of those receptors are involved in neuronal differentiation. For example, PPAR-γ activation was shown to induce neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells,48 while TRPV1 is involved in maintaining the [Ca2+] homeostasis which is primarily involved during the development and differentiation of the nervous system. TRPV1 expression and activity was found to be increased in SH-SY5Y upon neuronal differentiation.49 TRPV1 was also shown to be functionally expressed in PC12 cells,50 which also are able to synthesize AEA (27).51 Therefore, TRPV1 might be one of the candidates for the AEA-induced CB1 receptor-indpendent targets of neurite outgrowth shown in our report. The EMT inhibition could be the main mechanism of the neuritogenic effect shown by BSL34. The other bioactive compounds (10, 11, 17, 21, 23, and 24) still inhibit the EMT, although with a lower potency (20–25% inhibition of AEA (27) uptake at the screening concentration of 10 μM (Supporting Information Figure 4) and only show moderate FAAH inhibition (Supporting Information Figure 2).

In conclusion, our results suggest that the modulation of the endocannabinoid transport could be the main mechanism of farinosone C and analogs with respect to the neuritogenic effects. Nevertheless, further investigations on the precise involvement of the endocannabinoid system in neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells will be performed to clarify the observed biological effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Henning J. Jessen (University of Zurich, CH) and Dr. Linda D. Simmler (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, US) for their technical support with the biological experiments. Dr. Jennifer Zampese (University of Basel, CH) and Dr. Rosario Scopelliti (EPF Lausanne, CH) are acknowledged for the X-ray diffraction analysis.

Supporting Information Available

Complete experimental details and supporting figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) (200021-144028), the University of Bern Forschungsstiftung, and COST CM0804 is gratefully acknowledged.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper posted ASAP on December 17, 2013. Table 2 was replaced and the revised version was reposted on December 27, 2013.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gaugler J.; James B.; Johnson T.; Scholz K.; J W. 2013 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2013, 9, 208–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madathil M. M.; Khdour O. M. A Structurally Simplified Analogue of Geldanamycin Exhibits Neuroprotective Activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 953–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadimani M. B.; Purohit M. K.; Vanampally C.; Van der Ploeg R.; Arballo V.; Morrow D.; Frizzi K. E.; Calcutt N. A.; Fernyhough P.; Kotra L. P. Guaifenesin Derivatives Promote Neurite Outgrowth and Protect Diabetic Mice from Neuropathy. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5071–5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohda C.; Kuboyama T.; Komatsu K. Search for Natural Products Related to Regeneration of the Neuronal Network. Neurosignals 2005, 14, 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana C. K.; Hoecker J.; Woods T. M.; Jessen H. J.; Neuburger M.; Gademann K. Synthesis of Withanolide A, Biological Evaluation of its Neuritogenic Properties, and Studies on Secretase Inhibition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8407–8411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liffert R.; Hoecker J.; Jana C. K.; Woods T. M.; Burch P.; Jessen H. J.; Neuburger M.; Gademann K. Withanolide A: synthesis and structural requirements for neurite outgrowth. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2851–2857. [Google Scholar]

- Gao L.; Li J.; Qi J. Gentisides A and B, two new neuritogenic compounds from the traditional Chinese medicine Gentiana rigescens Franch. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2131–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L.; Xiang L.; Luo Y.; Wang G.; Li J.; Qi J. Gentisides C-K: Nine new neuritogenic compounds from the traditional Chinese medicine Gentiana rigescens Franch. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 6995–7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch P.; Binaghi M.; Scherer M.; Wentzel C.; Bossert D.; Eberhardt L.; Neuburger M.; Scheiffele P.; Gademann K. Total Synthesis of Gelsemiol. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 2589–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Ohizumi Y. Search for Constituents with Neurotrophic Factor-Potentiating Activity from the Medicinal Plants of Paraguay and Thailand. Yakugaku Zasshi 2004, 124, 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Trzoss L.; Chang W. K.; Theodorakis E. A. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Jiadifenolide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 123, 3756–3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenmoser A.; Wintner C. E. Natural Product Synthesis and Vitamin B12. Science 1977, 196, 1410–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward R. B. The Total Synthesis of Vitamin B12. Pure Appl. Chem. 1973, 33, 145–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Hale C. R. H.; Nilewski C. A Total Synthesis Trilogy: Calicheamicin γ1I, Taxol ®, and Brevetoxin A. Chem. Rec. 2012, 12, 407–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach J.-Y.; Gademann K. Reduce to the Maximum: Truncated Natural Products as Powerful Modulators of Biological Processes. Synlett 2011, 2012, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wender P. A.; Verma V. A.; Paxton T. J.; Pillow T. H. Function-Oriented Synthesis, Step Economy, and Drug Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towle M. J.; Salvato K. A.; Budrow J.; Wels B. F.; Kuznetsov G.; Aalfs K. K.; Welsh S.; Zheng W.; Seletsky B. M.; Palme M. H.; Habgood G. J.; Singer L. A.; Dipietro L. V.; Wang Y.; Chen J. J.; Quincy D. A.; Davis A.; Yoshimatsu K.; Kishi Y.; Yu M. J.; Littlefield B. A. In Vitro and In Vivo Anticancer Activities of Synthetic Macrocyclic Ketone Analogues of Halichondrin B. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1013–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher T. D.; Buszek K. R.; Fang F. G.; Forsyth C. J.; Jung S. H.; Kishi Y.; Matelich M. C.; Scola P. M.; Spero D. M.; Yoon S. K. Total Synthesis of Halichondrin B and Norhalichondrin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 3162–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid F.; Jessen H. J.; Burch P.; Gademann K. Truncated militarinone fragments identified by total chemical synthesis induce neurite outgrowth. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dakas P.-Y.; Parga J. A.; Höing S.; Schöler H. R.; Sterneckert J.; Kumar K.; Waldmann H. Discovery of Neuritogenic Compound Classes Inspired by Natural Products. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9576–9581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen H. J.; Schumacher A.; Shaw T.; Pfaltz A.; Gademann K. A Unified Approach for the Stereoselective Total Synthesis of Pyridone Alkaloids and Their Neuritogenic Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 4222–4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen H. J.; Barbaras D.; Hamburger M.; Gademann K. Total Synthesis and Neuritotrophic Activity of Farinosone C and Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3446–3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Schneider B.; Riese U.; Schubert B.; Li Z. Hamburger, M. Farinosones A-C, Neurotrophic Alkaloidal Metabolites from the Entomogenous Deuteromycete Paecilomyces farinosus. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1854–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S.; Schümann J.; Scherlach K.; Lange C.; Brakhage A. A.; Hertweck C. Genomics-driven discovery of PKS-NRPS hybrid metabolites from Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halo L. M.; Marshall J. W.; Yakasai A. A.; Song Z.; Butts C. P.; Crump M. P.; Heneghan M.; Bailey A. M.; Simpson T. J.; Lazarus C. M.; Cox R. J. Authentic Heterologous Expression of the Tenellin Iterative Polyketide Synthase Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Requires Coexpression with an Enoyl Reductase. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K.; Gunther W.; Stoyanova S.; Schubert B.; Li Z.; Hamburger M. Militarinone A, a Neurotrophic Pyridone Alkaloid from Paecilomyces militaris. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I.; Schlessinger J.; Lax I. PC12 cells overexpressing the insulin receptor undergo insulin-dependent neuronal differentiation. Curr. Biol. 1994, 4, 702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene L. A.; Tischler A. S. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1976, 2424–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A. M. Polyphenol oxidases in plants and fungi: Going places? A review. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2318–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser M. J.; Roth B. L.; Armbruster B. N.; Ernsberger P.; Irwin J. J.; Shoichet B. K. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortar G.; Ligresti A.; De Petrocellis L.; Morera E.; Di Marzo V. Novel selective and metabolically stable inhibitors of anandamide cellular uptake. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 65, 1473–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V.; Ligresti A.; Morera E.; Nalli M.; Ortar G. The anandamide membrane transporter. Structure-activity-relationships of anandamide and oleoylethanolamine analogs with phenyl rings in the polar head group region. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5161–5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V.; Capasso R.; Matias I.; Aviello G.; Petrosino S.; Borrelli F.; Romano B.; Orlando P.; Capasso F.; Izzo A. A. The role of endocannabinoids in the regulation of gastric emptying: alterations in mice fed a high-fat diet. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 153, 1272–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F.; Le Douaron G.; Champy P.; Amar M.; Seon-Meniel B.; Raisman-Vozari R.; Figadere B. Tryptamine-derived alkaloids from Annonaceae exerting neurotrophin-like properties on primary dopaminergic neurons. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 5103–5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. C.; Gomes I.; Nguyen T.; Jayaram G.; Ram P. T.; Devi L. A.; Iyengar R. The Gαo/i-coupled Cannabinoid Receptor-mediated Neurite Outgrowth Involves Rap Regulation of Src and Stat3. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33426–33434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J. D.; He J. C.; Eungdamrong N. J.; Gomes I.; Ali W.; Nguyen T.; Bivona T. G.; Philips M. R.; Devi L. A.; Iyengar R. Cannabinoid Receptor-induced Neurite Outgrowth is Mediated by Rap1 Activation through Gαo/i-triggered Proteasomal Degradation of Rap1GAPII. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11413–11421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Challapalli S. C.; Smith P. J. W. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation stimulates neurite outgrowth and inhibits capsaicin-induced Ca(2+) influx in an in vitro model of diabetic neuropathy. Neuropharmacology 2009, 57, 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicca A.; Marazzi J.; Gertsch J. The antinociceptive triterpene β-amyrin inhibits 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) hydrolysis without directly targeting cannabinoid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 1596–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong T. M.; Heymsfield S. B. Cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonists: current understanding of mechanism of action and unanswered questions. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R.; Liu Q.; Fan P.; Lin S.; Fernando S. R.; McCallion D.; Pertwee R.; Makriyannis A. Structure–Activity Relationships of Pyrazole Derivatives as Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicca A.; Marazzi J.; Nicolussi S.; Gertsch J. Evidence for Bidirectional Endocannabinoid Transport across Cell Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 34660–34682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanein P.; Javanmardi K. A potent and selective inhibitor of endocannabinoid uptake, UCM707, potentiates antinociception induced by cholestasis. Fund. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 22, 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lago E.; Fernández-Ruiz J.; Ortega-Gutiérrez S.; Viso A.; López-Rodriguez M. L.; Ramos J. A. UCM707, a potent and selective inhibitor of endocannabinoid uptake, potentiates hypokinetic and antinociceptive effects of anandamide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 449, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagon Y.; Avraham Y.; Link G.; Zolotarev O.; Mechoulam R.; Berry E. M. The synthetic cannabinoid HU-210 attenuates neural damage in diabetic mice and hyperglycemic pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 27, 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D.; Navarro B.; Martinez-Serrano A.; Guzman M.; Galve-Roperh I. The Endocannabinoid Anandamide Inhibits Neuronal Progenitor Cell Differentiation through Attenuation of the Rap1/B-Raf/ERK Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46645–46650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G. J.; Bönisch H.; Hammermann R.; Göthert M.; Brüss M. Noradrenaline release-inhibiting receptors on PC12 cells devoid of α2– and CB1 receptors: similarities to presynaptic imidazoline and edg receptors. Neurochem. Int. 2002, 40, 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotter E. L.; Goodfellow C. E.; Graham E. S.; Dragunow M.; Glass M. Neuroprotective potential of CB1 receptor agonists in an in vitro model of Huntington’s disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 747–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglio G.; Rosa A. C.; Rattazzi L.; Collino M.; Lombardi G.; Fantozzi R. PPARgamma stimulation promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and prevents glucose deprivation-induced neuronal cell loss. Neurochem. Int. 2009, 55, 496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaloussi-Lilja J. E.; Lundqvist J.; Forsby A. TRPV1 expression and activity during retinoic acid-induced neuronal differentiation. Neurochem. Int. 2009, 55, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya A.; Kunieda K.; Akiyama N.; Hirabayashi T.; Horie S.; Murayama T. Expression of vanilloid VR1 receptor in PC12 cells. Neurochem. Int. 2004, 45, 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T.; Katayama K.; Melck D.; Ueda N.; De Petrocellis L.; Yamamoto S.; Di Marzo V. Biosynthesis and degradation of bioactive fatty acid amides in human breast cancer and rat pheochromocytoma cells - Implications for cell proliferation and differentiation. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 254, 634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.