Abstract

A phenotypic high-throughput screen using ∼100,000 compounds prepared using Diversity-Oriented Synthesis yielded stereoisomeric compounds with nanomolar growth-inhibition activity against the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiological agent of Chagas disease. After evaluating stereochemical dependence on solubility, plasma protein binding and microsomal stability, the SSS analogue (5) was chosen for structure–activity relationship studies. The p-phenoxy benzyl group appended to the secondary amine could be replaced with halobenzyl groups without loss in potency. The exocyclic primary alcohol is not needed for activity but the isonicotinamide substructure is required for activity. Most importantly, these compounds are trypanocidal and hence are attractive as drug leads for both acute and chronic stages of Chagas disease. Analogue (5) was nominated as the molecular libraries probe ML341 and is available through the Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network.

Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, diversity-oriented synthesis, Chagas disease, neglected disease, high-throughput screening, phenotypic assay, infectious disease, Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network

Chagas disease (CD) affects approximately 10 million people and yet continues to be one of the most neglected diseases in terms of new drug development.1,2 CD is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and is endemic to Central and South America where there is a direct vector transmission of the parasite to humans. CD is also spreading in the United States, Europe, and Australia mainly through patient migration.3 Impoverished people disproportionately carry a higher burden of CD due to inadequate access to clean living facilities and close proximity to infected animals and livestock. CD manifests in two stages: an acute phase and a chronic phase.4 The acute phase can last a few weeks and may either be asymptomatic or show nonunique symptoms such as fever, headache, body ache, and fatigue. If left untreated, infected patients enter the chronic phase of the disease. Decades after the initial infection, some patients in the chronic phase develop cardiac or intestinal complications leading to sudden death.

Currently benznidazole (1) and nifurtimox (2) are the only drugs available for treating the acute phase of CD (Figure 1). However, both the drugs have significant adverse effects resulting in poor patient compliance.4 In addition to these drawbacks, resistance has emerged to both the drugs as they have been in use for over 30 years.5 Although a clinical trial is underway for evaluating the efficacy of benznidazole, currently there are no approved drugs for treating the chronic phase of CD. The antifungal drugs posaconazole and the pro-drug of ravuconazole (E1224) are in clinical trials for CD and both of them target CYP51 of T. cruzi.6 Preclinical research involving other CYP51 inhibitors is also encouraging.7,8 In addition, cruzain has emerged as an important target for developing anti-Chagas drugs.9 Advanced preclinical studies have been completed with fexinidazole, an analogue of benznidazole.10 New drugs that are safe and efficacious are critically needed to treat millions of people suffering from CD.

Figure 1.

Current drugs for treating Chagas disease.

We conducted a phenotypic11,12 High-Throughput Screen (HTS) with approximately 100,000 small molecules derived from Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) to identify novel growth inhibitors of T. cruzi, and the results are reported in PubChem.13 Compared to compounds in the commercial vendor libraries, DOS compounds have novel ring architectures and contain several stereocenters and a higher extent of sp3-hybridized carbon atoms.14,15 In addition, the DOS pathways exploit the power of modern organic chemistry, and hence, the resulting DOS libraries efficiently populate small, medium, and macrocyclic chemical space.16 The design features of our DOS libraries include comprehensive stereochemical diversity on all the cores and structural diversity through variations in building blocks.17−19 Hence, results from HTS directly provide both structure–activity relationships (SAR) and SAR based on stereochemical variation.20

In this communication, we report the SAR surrounding one of the hits from the SNAr-8-ortho library21 using two different T. cruzi growth inhibition assays, and we also demonstrate that this structural class exhibits trypanocidal activity making it a candidate for developing a new class of drug against both acute and chronic stages of CD.

A set of eight stereoisomers (Table 1, 3–10) was identified comprising potent growth inhibitors of T. cruzi. The primary assay was conducted using the recombinant Tulahuen strain of T. cruzi stably expressing beta-galactosidase reporter that is cocultured with the host cell, mouse fibroblast NIH/3T3.22 In this assay, compounds were added to the host cell, then infected with T. cruzi and incubated for 4 days. The observed growth inhibition could be through one or more of the following three modes. The compound could kill the extracellular trypomastigote form of T. cruzi or it might prevent invasion into the host cell or act on the clinically relevant intracellular amastigote form of T. cruzi, which is involved in replication. All compounds were counter-screened against the host cell to remove compounds showing nonspecific toxicity and in general most compounds showed T.cruzi specific toxicity.23 The T. cruzi growth inhibition activities from this assay are reported as multimode throughout this letter.

Table 1. T. cruzi Growth Inhibition, Plasma Protein Binding, Solubility, and Microsomal Stability of Eight Stereoisomers.

|

T. cruzi (IC50, nM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | configuration (C2C5C6) | relative configuration (C5C6) | multimode | amastigote | plasma protein binding (human) | PBS solubility (μM) | microsome stabilitya (mouse) |

| 3 | SRR | trans | 1 | 24 | 99% | 1 | 2% |

| 4 | RRR | trans | 5 | 22 | 99% | 1 | 1% |

| 5 | SSS | trans | 1 | 16 | 99% | 1 | 77% |

| 6 | RSS | trans | 2 | 31 | 99% | 2 | 70% |

| 7 | SRS | cis | 450 | 670 | 95% | 87 | <1% |

| 8 | SSR | cis | 23 | 59 | 95% | 93 | <1% |

| 9 | RRS | cis | 260 | 1200 | 95% | 86 | <1% |

| 10 | RSR | cis | 16 | 75 | ND | 98 | <1% |

Amount remaining after 1 h of incubation with 1 μM of the compound.

All eight stereoisomers had submicromolar activity against T. cruzi in the multimode growth inhibition assay. In general, the four stereoisomers with trans configuration across C5C6 showed higher potency (3–6, IC50 around 1 nM) than the corresponding analogues with the cis configuration (7–10, IC50s in the range of 16–450 nM).

We then investigated if these compounds inhibited the growth of the clinically relevant replicating amastigotes using the same strain of T. cruzi but with rat myoblasts as the host cell (L-6 cells).23 Seven of the eight stereoisomers demonstrated submicromolar activity and the trans isomers (3–6) were once again more potent than the corresponding cis isomers (7–10).

Since several stereoisomers demonstrated low nanomolar anti-T.cruzi activities, we profiled all the stereoisomers in a limited set of in vitro ADME assays to identify the optimal stereoisomer for investigating SAR. All the trans isomers (3–6) were highly bound to human plasma proteins, but the cis isomers (7–9) showed 5% free fraction. The RSR isomer (10) was unstable in human plasma. Solubility in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) showed similar trend for favorability. The cis isomers were more soluble in PBS (7–10, 87–98 μM) than the corresponding trans isomers (3–7, 1–2 μM). However, only the SSS stereoisomer (5) and the RSS stereoisomer (6) had appreciable mouse microsomal stability. On the basis of potency and the microsomal stability, we decided to investigate the SAR with the SSS stereoisomer.

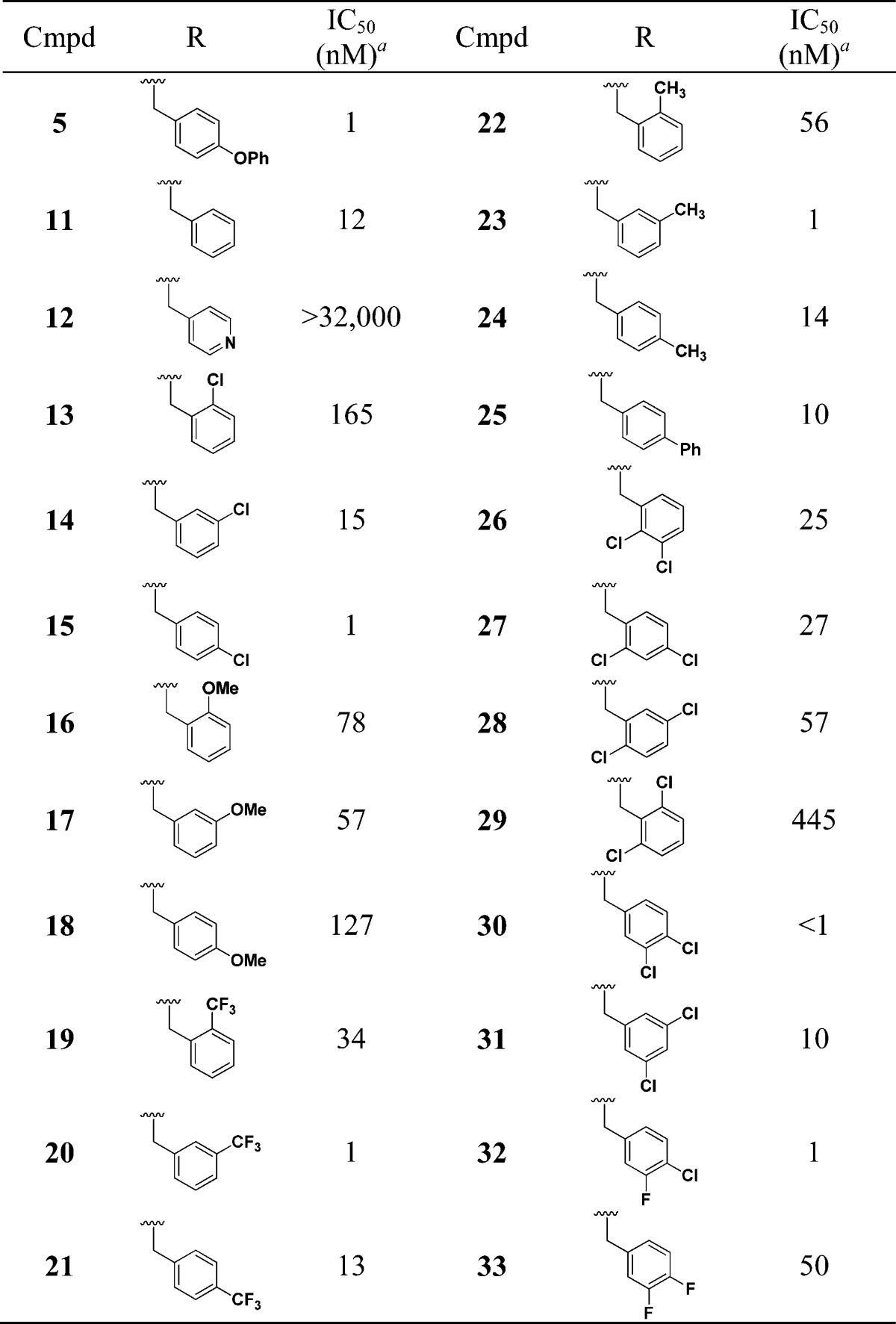

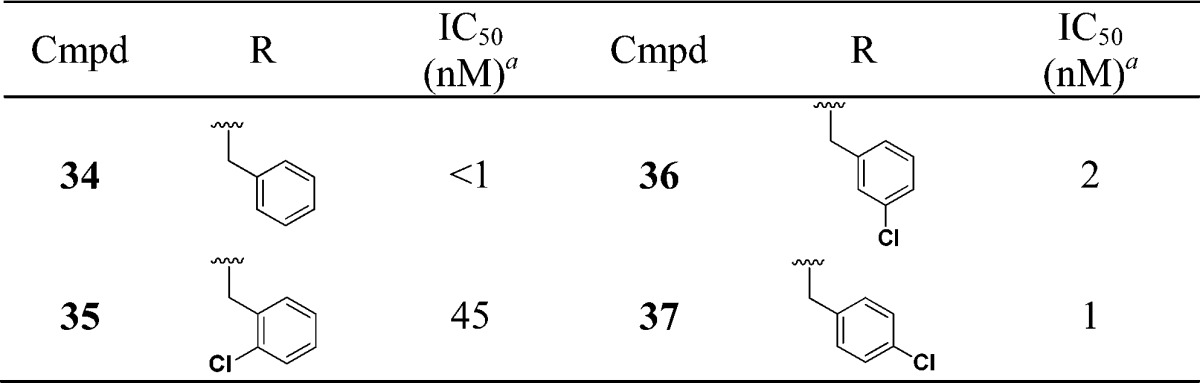

We first looked at replacing the p-phenoxybenzyl group, and these results are summarized in Table 2. The multimode growth inhibition assay was used for driving the SAR studies. The benzyl analogue (11) not only retained activity (12 nM) but improved PBS solubility to 100 μM. The 4-pyridyl analogue (12) also had good PBS solubility (100 μM) but was inactive. The chlorobenzyl (13–15), methoxybenzyl (16–18), trifluoromethylbenzyl (19–21), and tolyl (22–24) analogues were also nanomolar inhibitors of T. cruzi.23 Since chloro substitution is tolerated on the meta and para positions of the aromatic ring, we evaluated a number of dihalo analogues (26–33). With the exception of the 2,6-dichloro analogue (29), all the dihalo analogues showed excellent T. cruzi growth inhibition. In particular, the 3,4-dichloro analogue (30) showed IC50 in the subnanomolar range and with 64 μM solubility in PBS. Overall, multiple groups are tolerated on the secondary amine.

Table 2. SAR by Varying Amine Substituent.

Multimode T. cruzi growth inhibition assay.

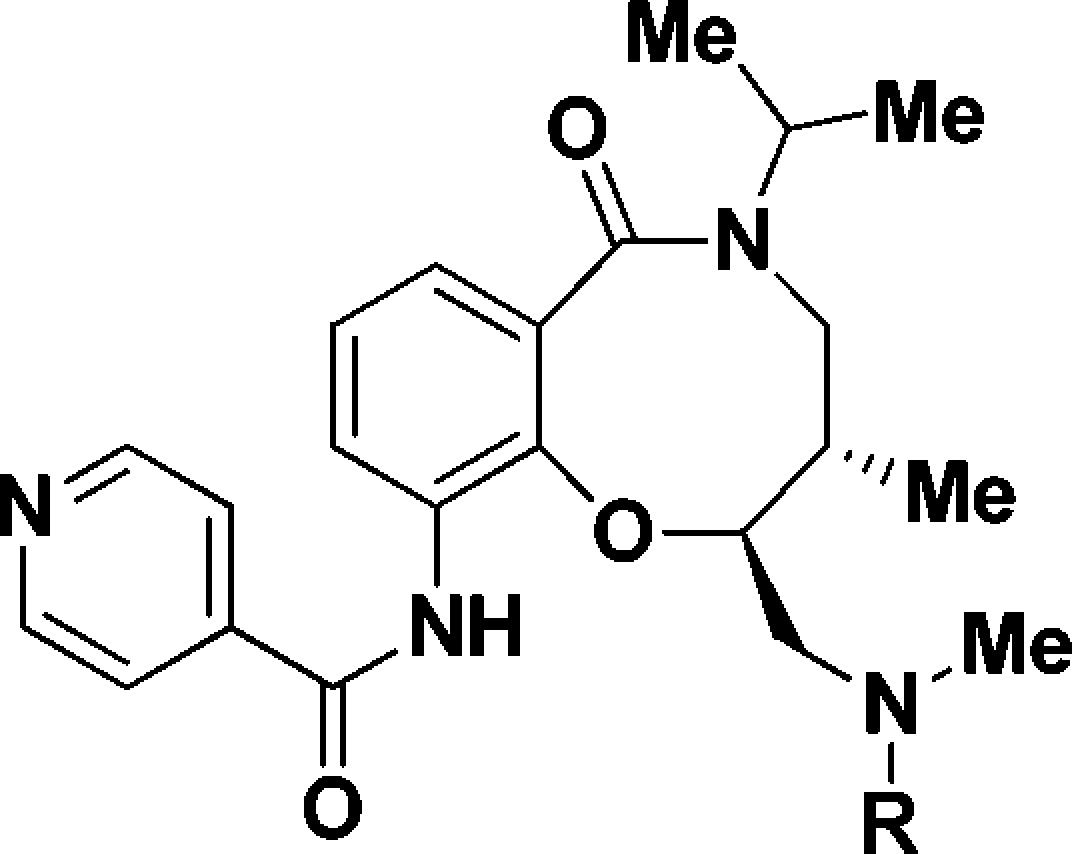

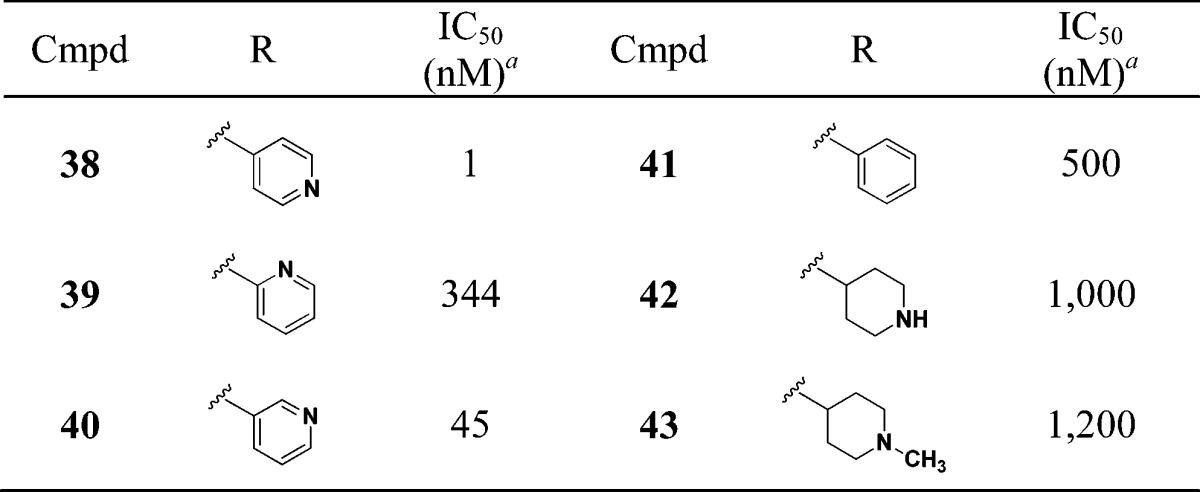

We next evaluated the replacement of the exocyclic primary alcohol unit with a simple isopropyl group, and the resulting SAR is shown in Table 3. The benzyl (34) and the chlorobenzyl (35–37) analogues were all nanomolar inhibitors of T. cruzi growth. SAR surrounding the amide substructure was then briefly evaluated keeping the p-phenoxy benzyl substituent constant, and these results are shown in Table 4. The 4-pyridyl analogue (38) retained activity. The 2-pyridyl (39) and 3-pyridyl (40) analogues were less active. The phenyl (41) and the piperidyl (42 and 43) analogues were significantly less potent.

Table 3. SAR with N-Isopropyl Substituent.

Multimode T. cruzi growth inhibition assay.

Table 4. SAR on the Amide Portion.

Multimode T. cruzi growth inhibition assay.

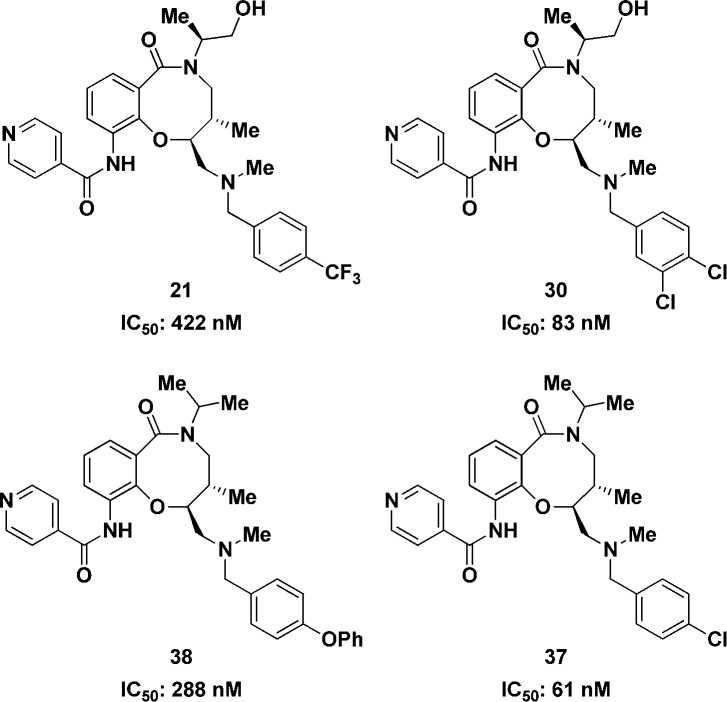

Since most of the SAR studies were conducted with the multimode growth inhibition assay, we evaluated a set of 15 analogues in the amastigote growth inhibition assay. A representative set of examples is shown in Figure 2.23 Replacing the phenoxy group (5, 16 nM, Table 1) with the trifluoromethyl group (21) resulted in more than 100-fold loss in potency against amastigotes. The 3,4-dichlorobenzyl analogue (30) was potent with 83 nM activity. The isopropyl analogue with the p-phenoxybenzyl substituent demonstrated 288 nM potency. The corresponding p-chlorobenzyl analogue (37) was more potent with an IC50 of 61 nM.

Figure 2.

Amastigote growth inhibition activity.

We next evaluated the trypanocidal activity through an experiment using the clinical isolate of T. cruzi CA-I/72 strain, which is cardiotropic in mouse models.24T. cruzi infected bovine embryo skeletal muscle cells (BESM) were treated with varying concentrations of the compound for 20 or 29 days and maintained for up to 36 days post-treatment. Compounds were refreshed every other day during the treatment phase, and the emergence of trypomastigotes was visually determined daily during the treatment and the post-treatment phases. Under these conditions, T. cruzi completes the intracellular life cycle in 6 days in untreated controls, and the trypomastigotes can be detected in the medium. If a compound only inhibits replication, the day of trypomastigote emergence will only be delayed, and the compound is considered to be trypanostatic. However, if a compound completely kills the parasite at the test concentration, trypomastigotes will not appear at any point even during the post-treatment monitoring period of 36 days that corresponds to 6 life cycles of T. cruzi. Such a compound is considered to be trypanocidal at that test concentration.

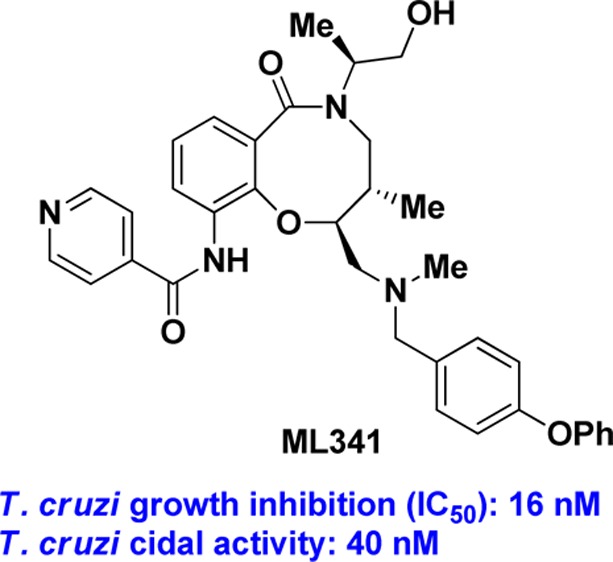

Five stereoisomers representing both cis and trans configurations across C5C6 were evaluated in this trypanocidal assay, and the results are shown in Table 5.23 When treated for 29 days, the SSS analogue (5) was trypanocidal at 40 nM since trypomastigote re-emergence was not observed up to 36 days post-treatment. With the shorter treatment of 20 days, the SSS analogue was trypanocidal at 740 nM. SRR analogue (3), RRR analogue (4), and SSR analogue (8) were also trypanocidal at 40 nM with 29 days of treatment. The RSR analogue (10) was trypanocidal only at a higher dose of 370 nM. Under these assay conditions, the current first line drug benznidazole (1) was trypanocidal only at 6.6 μM. On the basis of the potency in the trypanocidal assay and the enhanced microsomal stability, we nominated the SSS analogue (5) as the molecular libraries probe ML341, and this compound is available through the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN).

Table 5. Trypanocidal assay results.

| number of days |

parasite

re-emergence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | dose (nM) | during treatment | post-treatment | during treatment | post-treatment |

| 5 ML341 | 40 | 29 | 36 | no | no |

| 5 | 250 | 20 | 4 | yes | yes, after 4 days |

| 5 | 740 | 20 | 37 | no | no |

| 3 | 40 | 29 | 36 | no | no |

| 4 | 40 | 29 | 36 | no | no |

| 8 | 40 | 29 | 36 | no | no |

| 10 | 370 | 29 | 36 | no | no |

| 1 | 6,600 | 20 | 37 | no | no |

In summary, we have identified a novel small molecule derived from Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) with excellent trypanocidal activity. Since tryponocidal activity is necessary for treating the chronic phase of Chagas disease, ML341 is an attractive starting point for developing drugs against both acute and chronic stages of Chagas disease. Results from further optimization of ML341 will be reported in subsequent publications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Johnston and John Athanasopoulos for analytical chemistry and compound management support. S.L.Q. thanks the Danish Council for Independent Research and Lundbeck Foundation for financial support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- CD

Chagas disease

- DOS

diversity-oriented synthesis

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- MLPCN

Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- ADME

absorption distribution metabolism elimination

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- BESM

bovine embryo skeletal muscle cells

Supporting Information Available

Representative synthesis of new compounds. UPLC purity, PBS solubility, plasma protein binding, and counter screen results (host cell toxicity) of all analogues. Experimental details of growth inhibition and trypanocidal assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

This work was funded by the NIH’s MLPCN program (1 U54 HG005032-1 (awarded to S.L.S).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Chagas disease 101. Nature 2010, 465, S4–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research priorities for Chagas disease, human African Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization’s Technical Report Series 2012, 975, 1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C.; Kjos S.; Yabsley M. J.; Montgomery S. P. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 655–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas’ disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2527–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun O.; Lima M. A.; Ellman T.; Chambi W.; Castillo S.; Flevaud L.; Roddy P.; Parreno F.; Vinas P. A.; Palma P. P. Feasibility, drug safety, and effectiveness of etiological treatment programs for Chagas disease in Honduras, Guatemala, and Bolivia: 10-year experience of Me’decins Sans Frontie’res. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas disease: pushing through the pipeline. Nature 2010, 465, S13–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalta F.; Dobish M. C.; Nde P. N.; Kleshchenko Y. Y.; Hargrove T. Y.; Johnson C. A.; Waterman M. R.; Johnston J. N.; Lepesheva G. I. VNI cures acute and chronic experimental Chagas disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilleke S. S.; Calvet C. M.; Johnston J. B.; Chen C. K.; Erenburg G.; Gut J.; Engel J. C.; Ang K. K.; Mulvaney J.; Chen S.; Arkin M. R.; McKerrow J. H.; Podust L. M. Diverse inhibitor chemotypes targeting Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51. PLoS. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajid M.; Robertson S. A.; Brinen L. S.; McKerrow J. H. Cruzain: the path from target validation to the clinic. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 712, 100–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahia M. T.; de Andrade I. M.; Martins T. A.; do Nascimento Á. F.; Diniz Lde F.; Caldas I. S.; Talvani A.; Trunz B. B.; Torreele E.; Ribeiro I. Fexinidazole: a potential new drug candidate for Chagas disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butera J. A. Phenotypic screening as a strategic component of drug discovery programs targeting novel antiparasitic and antimycobacterial agents: an editorial. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7715–7718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes M. L.; Avery V. M. Approaches to protozoan drug discovery: phenotypic screening. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7727–7740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assay/assay.cgi?aid=624255 (accessed Dec 21, 2013).

- O’Connell K. M. G.; Galloway W. R. J. D.; Spring D. R.. The basics of diversity-oriented synthesis. In Diversity Oriented Synthesis: Basics and Applications in Organic Synthesis, Drug Discovery and Chemical Biology; Trabocchi A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 2013; pp 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dandapani S.; Marcaurelle L. A. Accessing new chemical space for ‘undruggable’ targets. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 861–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. L. Organic synthesis toward small-molecule probes and drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 26, 6699–6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaurelle L. A.; Comer E.; Dandapani S.; Duvall J. R.; Gerard B.; Kesavan S.; Lee M. D.; Liu H.; Lowe J. T.; Marie J. C.; Mulrooney C. A.; Pandya B. A.; Rowley A.; Ryba T. D.; Suh B. C.; Wei J.; Young D. W.; Akella L. B.; Ross N. T.; Zhang Y. L.; Fass D. M.; Reis S. A.; Zhao W. N.; Haggarty S. J.; Palmer M.; Foley M. A. An aldol-based build/couple/pair strategy for the synthesis of medium- and large-sized rings: Discovery of macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16962–16976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. T.; Lee M. D.; Akella L. B.; Davoine E.; Donckele E. J.; Durak L.; Duvall J. R.; Gerard B.; Holson E. B.; Joliton A.; Kesavan S.; Lemercier B. C.; Liu H.; Marié J. C.; Mulrooney C. A.; Muncipinto G.; Welzel-O’Shea M.; Panko L. M.; Rowley A.; Suh B. C.; Thomas M.; Wagner F. F.; Wei J.; Foley M. A.; Marcaurelle L. A. Synthesis and profiling of a diverse collection of azetidine-based scaffolds for the development of CNS-focused lead-like libraries. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7187–7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard B.; Duvall J. R.; Lowe J. T.; Murillo T.; Wei J.; Akella L. B.; Marcaurelle L. A. Synthesis of a stereochemically diverse library of medium-sized lactams and sultams via SNAr cycloetherification. ACS Comb. Sci. 2011, 13, 365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrooney C. A.; Lahr D. L.; Quintin M. J.; Youngsaye W.; Moccia D.; Asiedu J. K.; Mulligan E. L.; Akella L. B.; Marcaurelle L. A.; Montgomery P.; Bittker J. A.; Clemons P. A.; Brudz S.; Dandapani S.; Duvall J. R.; Tolliday N. J.; De Souza A. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 455–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou D. H.; Duvall J. R.; Gerard B.; Liu H.; Pandya B. A.; Suh B. C.; Forbeck E. M.; Faloon P.; Wagner B. K.; Marcaurelle L. A. Synthesis of a novel suppressor of beta-cell apoptosis via diversity-oriented synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettiol E.; Samanovic M.; Murkin A. S.; Raper J.; Buckner F.; Rodriguez A. Identification of three classes of heteroaromatic compounds with activity against intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi by chemical library screening. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See Supporting Information for details

- Doyle P. S.; Zhou Y. M.; Hsieh I.; Greenbaum D. C.; McKerrow J. H.; Engel J. C. The Trypanosoma cruzi protease cruzain mediates immune evasion. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.