Abstract

Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic receptor via positive allosteric modulation represents an original approach to treat the cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. A series of naphthyl-fused 5-membered lactams were identified as a new class of M1 positive allosteric modulators and were found to possess good potency and in vivo efficacy.

Keywords: M1, muscarinic, positive allosteric modulators, Alzheimer’s disease, acetylcholine

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease representing one of the largest unmet medical needs in human heath today. One of the hallmarks of AD is the progressive degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain leading to cognitive decline.1 Acetylcholine, the key neurotransmitter in cholinergic neurons, targets both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Muscarinic receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) widely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS). There are five subtypes in the muscarinic family, designed M1–M5,2,3 of which M1 receptor is the most abundantly expressed in the hippocampus, cortex,4 and striatum, suggesting a prominent role in memory and cognition.

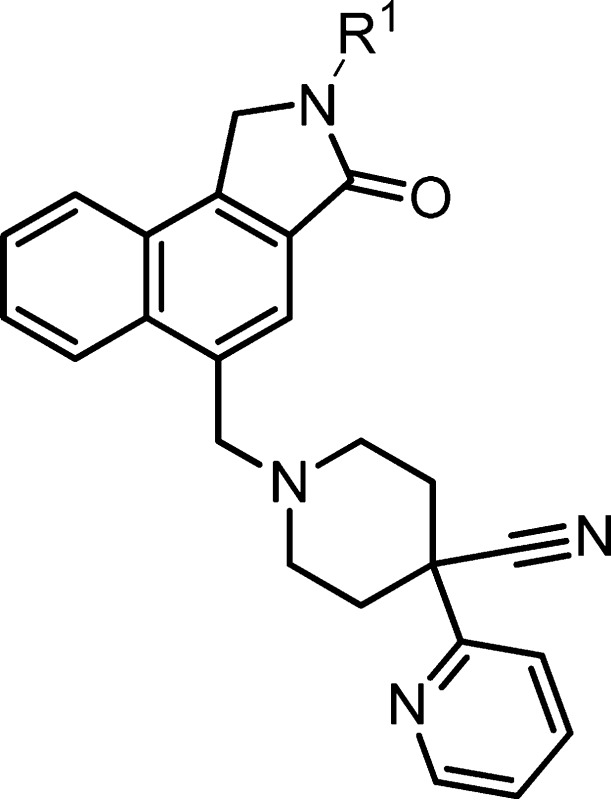

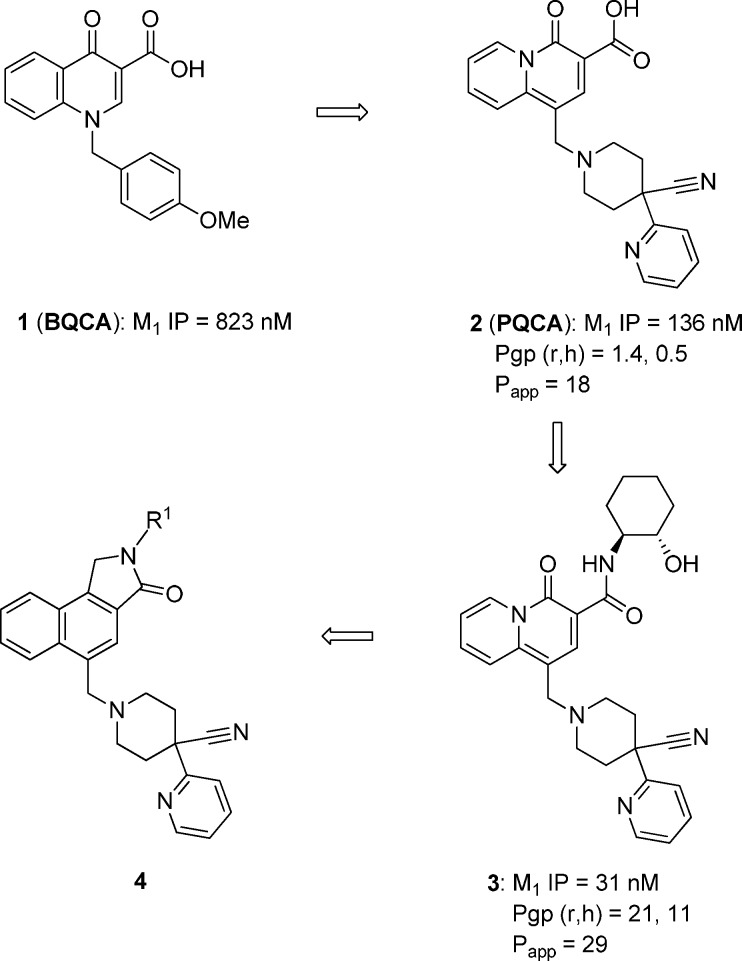

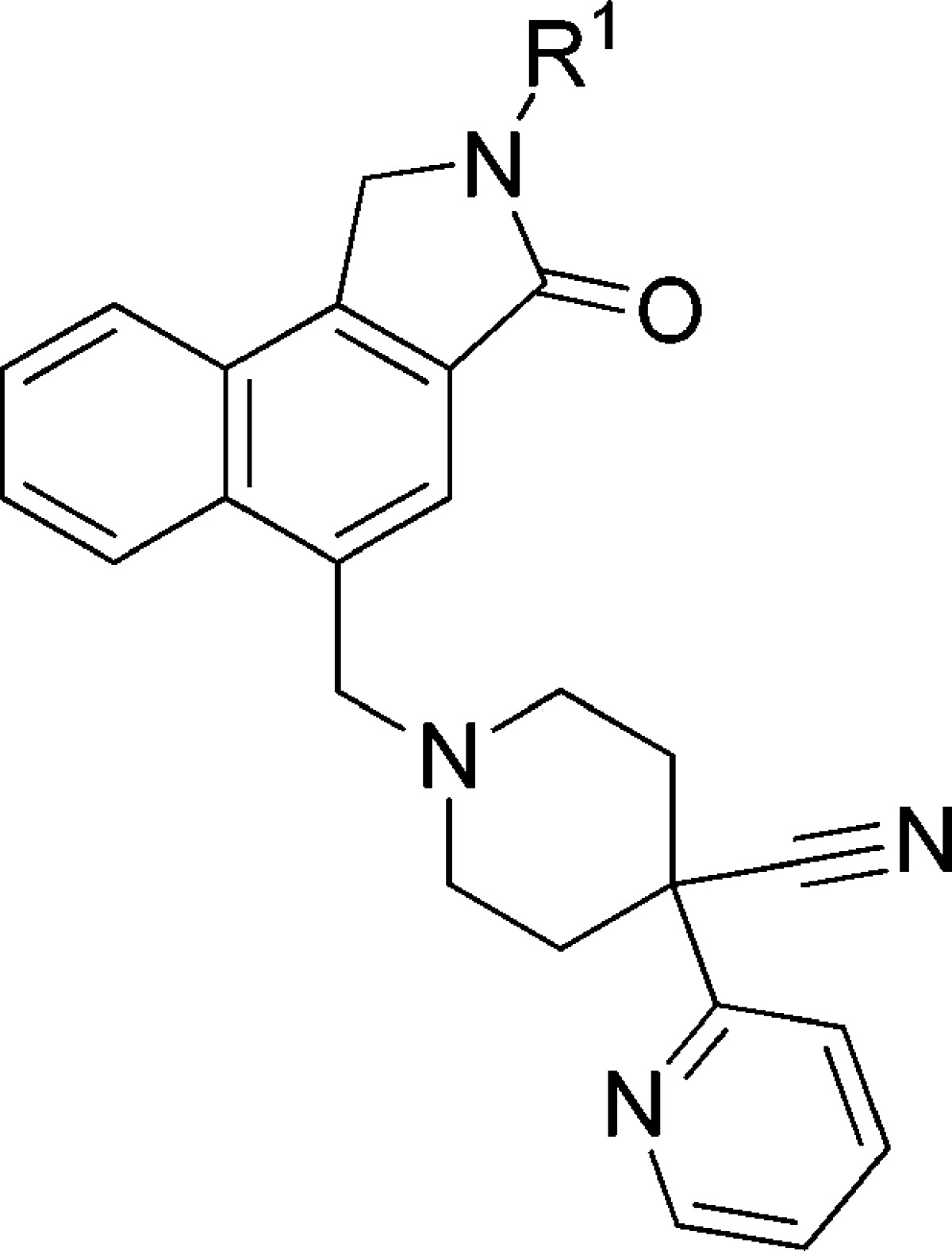

As a result, significant interest has been placed on developing selective M1 agonists in order to minimize adverse gastrointestinal events associated with activation of the other muscarinic subtypes.5 One approach to achieve selectivity is to target allosteric sites on M1 that are less conserved than the orthosteric site.6−8 To this end, we have previously reported several highly promising selective allosteric positive modulators of M1, derived from the original HTS lead, quinolone carboxylic acid 1 (BQCA).9−14 Efforts to improve the potency and brain penetration led to structural modification in the form of a quinolizidinone ring system, such as 2 (PQCA).15−17 More recent efforts focused on identification of replacements for the carboxylic acid to enhance CNS exposure and avoid clearance of the parent via the glucuronidation pathway.18 Accordingly, quinolizidinone carboxamide 3 was identified and provided significant improvement with respect to potency while maintaining excellent selectivity over other muscarinic receptors.19 However, compound 3 was found to be a substrate for the multidrug resistant (MDR) efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which serves as the major efflux transporter of xenobiotics at the blood–brain barrier.20 Amides were identified that dialed out the P-gp efflux and led to M1 PAMs with good brain penetration and free drug concentration.19 However, it was hoped that the 1S,2S-2-hydroxy cyclohexyl group present in 3, which provided excellent potency, could be utilized in a scaffold distinct from the quinolizidinone amide. Herein we report the discovery of a novel class of M1 allosteric modulators derived from a naphthyl lactam core (4) that maintain the high potency without being substrates for P-gp.

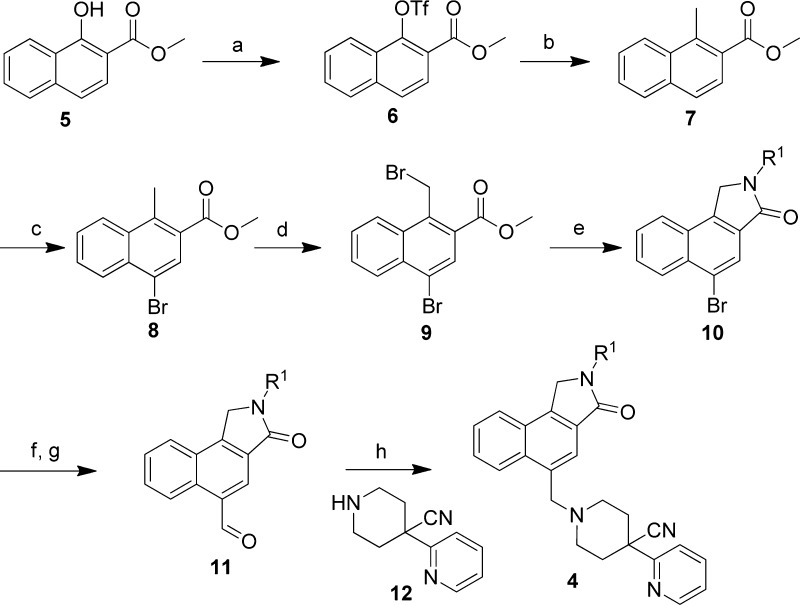

The preparation of the analogues of naphthyl lactam 4 is shown in Scheme 1. Starting from 1-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid methyl ester 5, triflate (6) formation is followed by Stille cross-coupling to provide 1-methyl derivative 7. Selective bromination at the C-4 position with bromine provided compound 8. A second bromination at the C-1 methyl group with NBS provided dibromo intermediate 9. Condensation with amines afforded lactam 10. The bromo group at C-4 was then transformed to an aldehyde via the standard two-step protocol: vinylation via Suzuki followed by ozonolysis. To complete the synthesis, reductive amination with previously reported piperidine 12(17) led to final product 4.

Scheme 1.

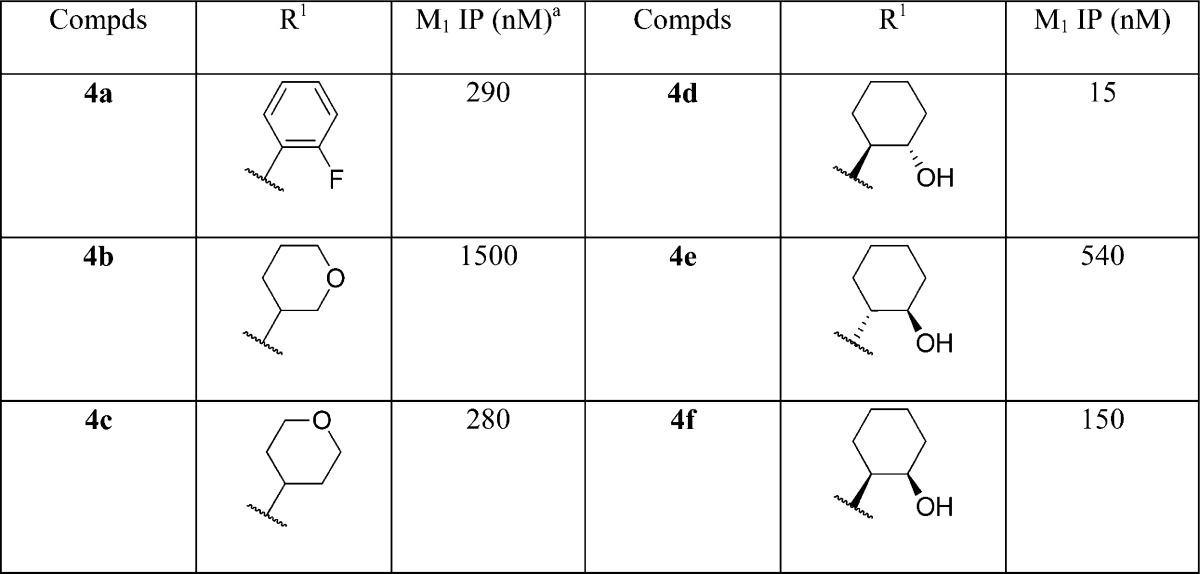

Compound potencies were determined in the presence of an EC20 concentration of acetylcholine at human M1 expressing CHO cells using calcium mobilization readout on a FLIPR384 fluorometric imaging plate reader. A number of analogues with varied substituents on the lactam nitrogen were synthesized as described in Scheme 1. Representative examples are shown in Table 1. Not surprisingly, compound 4d bearing the aforementioned 1S,2S-2-hydroxy cyclohexyl group off the lactam is the most potent compound among various R1 groups explored and displayed an M1 IP value of 15 nM. This specific stereochemistry was critical for potency as the associated 1R,2R-trans isomer 4e and cis isomer 4f were both significantly less active. ortho-Fluoro phenyl lactam 4a gave only moderate potency with an M1 IP value of 290 nM, approximately 5-fold less potent than 4d. Similar potency was observed with 4-tetrahydropyran lactam 4b (M1 IP = 280 nM). However, the corresponding 3-pyran (4c) was ∼5-fold weaker. It is worth noting that this SAR pattern at the R1 position was consistent with previously reported quinolizidinone amides.19 Moreover, it is important to recognize that this new naphthyl fused lactam still provides potent M1 PAMs such that cyclization of the amide in 3 into a lactam is tolerated and that the quinolizidinone can indeed be replaced by the naphthalene ring system. This shows that the carbonyl moiety present in previous quinolone and quinolizidinone M1 PAMs is not required for activity. As a novel class of M1 PAM, selected lactams were profiled in functional assays at other muscarinic subtypes and showed no activity at M2, M3, or M4 receptors, indicating that lactams maintain selectivity for M1.

Table 1. SAR on N-Substitution of Lactams.

Values represent the numerical average of at least two experiments. Interassay variability was ±30% (IP, nM), unless otherwise noted.

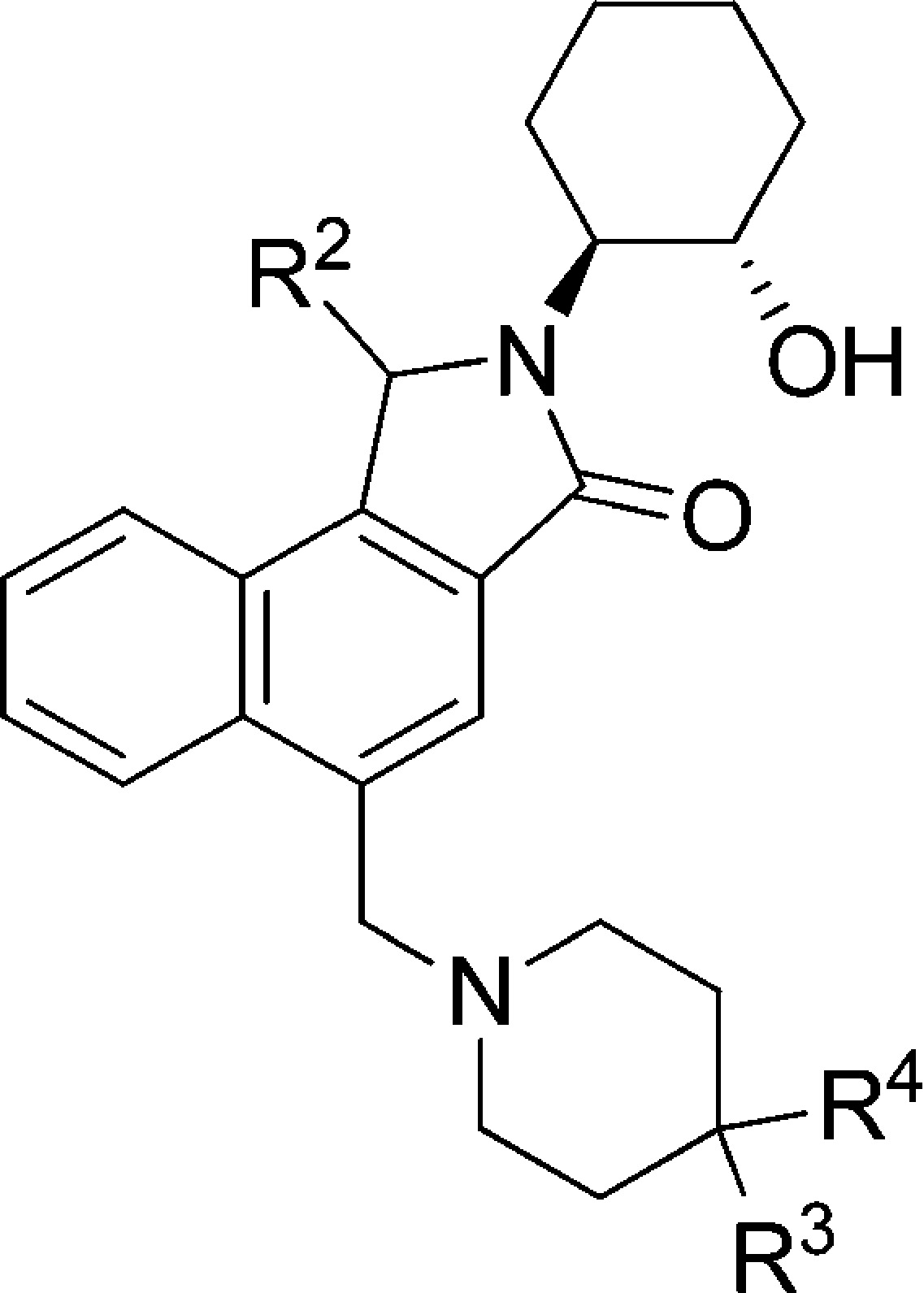

Having identified the naphthyl lactam as a potent new structural class, it was important to verify if it showed an advantage over amide 3 with respect to reduced P-gp efflux. Plasma protein binding was also determined using the equilibrium dialysis method in the presence of rat and human serum. The most potent lactam 4d did indeed display significantly reduced efflux and was a borderline substrate for human and rat P-gp with efflux ratios (ERs) of 3.2 and 4.3, respectively (Table 2). This is a significant improvement over the analogous quinolizidinone amide 3, with efflux ratios (ERs) of 11 and 21, respectively (Figure 1). Compound 4d also displayed excellent passive-permeability and good unbound fraction in plasma (5% in rat and 8% in human).

Table 2. M1 FLIPR, Protein Binding, and Pgp Data for Selected Compounds.

Values represent the numerical average of at least two experiments. Interassay variability was ±30% (IP, nM), unless otherwise noted.

Passive permeability (10–6 cm/s).

MDR1 directional transport ratio (B to A)/(A to B). Values represent the average of three experiments, and interassay variability was ±20%.

Figure 1.

Evolution of M1 PAM.

In order to further identify non-P-gp substrates, an SAR campaign was initiated on the amine motif. When the 2-pyridyl at R3 was replaced with other pyridines (4g and 4h) or less basic diazines (4i–k), the M1 potency was maintained but the P-gp ERs increased. Next, a methyl group was placed at key positions on the pyridine ring. The ortho-methyl analogue 4l was found not to be a human P-gp substrate, while the rat P-gp ER was also improved. The para-methyl compound 4m also showed similar advance on human P-gp but not on rat. Although both methyl analogues showed similar potency and reduced P-gp efflux compared to 4d, they were considerably more lipophilic and showed very high plasma protein binding at ∼99%. When the 2-pyridine was replaced with a phenyl group, compound 4n showed reduced P-gp efflux as expected, but at the expense of a ∼5-fold loss of potency. The phenyl replacement also resulted in higher plasma protein binding for 4n. A similar SAR trend was observed when exchanging CN group with F: compound 4o showed a loss of ∼4-fold of M1 potency but did have reduced P-gp efflux. In addition, the methyl group could be introduced onto benzylic position of lactam ring (R2). In this case, racemic product 4p maintained potency and showed improved human P-gp efflux. Compound 4p also retained a reasonable unbound free fraction despite the addition of the methyl group but was more lipophilic with a logP of 3.3.

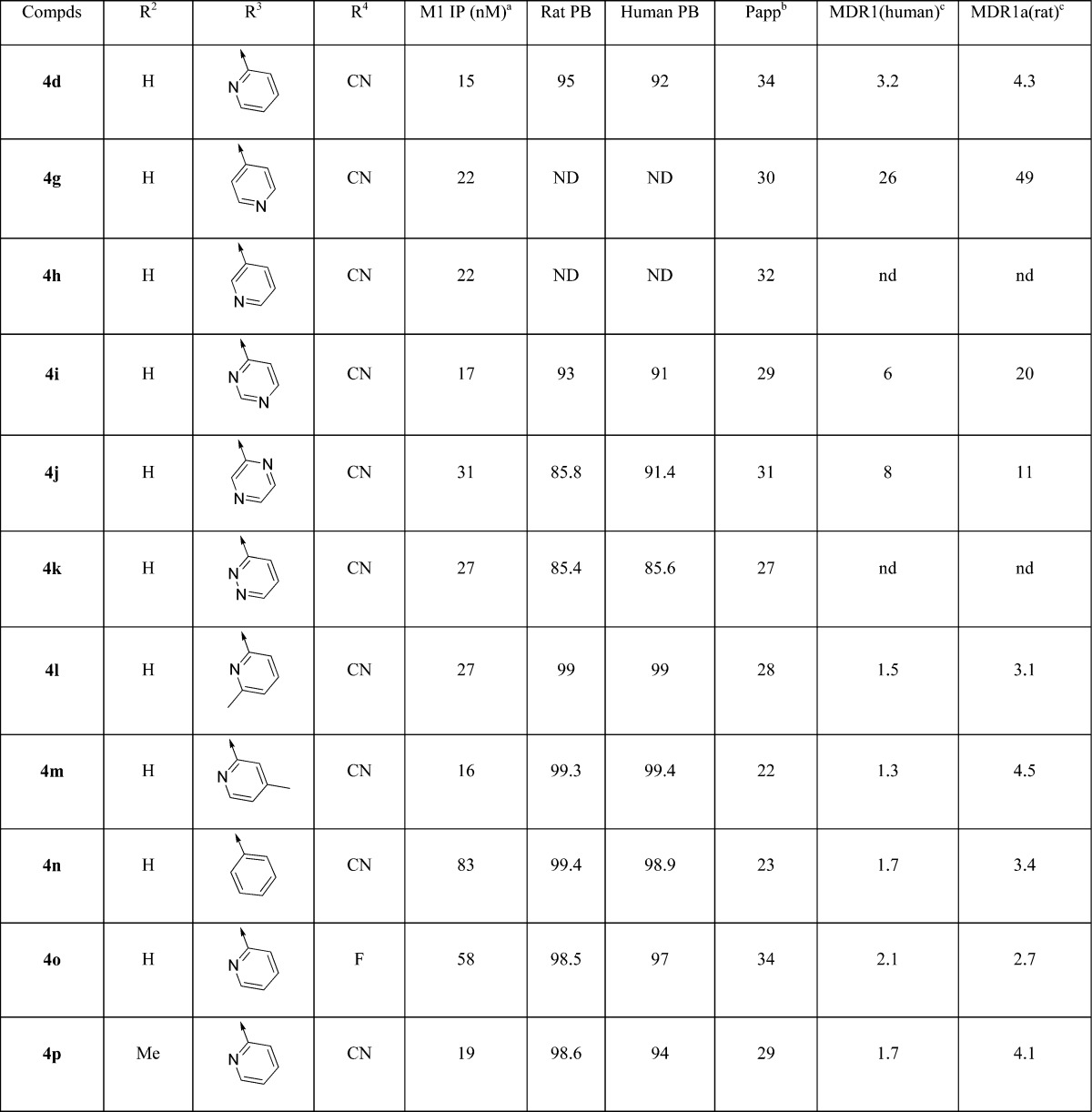

On the basis of the potency, P-gp profile, and free fraction properties, compounds 4d, 4m, and 4p were selected as candidates to determine the CNS exposure in rats (Table 3). Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels were measured after 2 h following a 10 mg/kg oral dose. Compound 4d gave significant plasma (5.2 uM) and CSF (134 nM) levels with a CSF/Uplasma ratio of 0.51. Although compound 4p provided a similar CSF/Uplasma ratio (0.52) compared to 4d, the absolute CSF level (8.6 nM) was significantly lower. The other methyl analogue 4m gave a moderately reduced CSF/Uplasma ratio (0.3) as well as low absolute CSF level (4.7 nM). The high CSF level of 4d was believed to be driven by higher unbound drug concentration than the corresponding methyl analogues 4m and 4p. Consistent with their increased protein binding, methyl analogues 4m and 4p have higher measured logP values than 4d. All three compounds showed excellent solubility at pH 2 (existed as salt form) but poor solubility at pH 7 (neutral form).

Table 3. Brain and Plasma Distribution in Rats for Selected Compounds.

Sprague–Dawley rats, concentration at 2 h postdose. Oral dose 10 mg/kg in 0.5% methocel. Interanimal variability was less than 20% for all values.

Determined using rat plasma protein binding from Table 2.

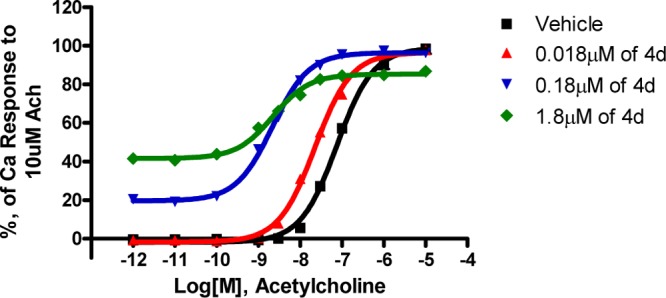

On the basis of the robust CSF levels of compound 4d, further studies were performed to investigate the properties of this new class of lactam-derived M1 modulators. Fold potentiation with a fixed concentration of modulator 4d was evaluated on the M1 dose response with acetylcholine as the agonist. As shown in Figure 2, with increasing concentration of compound 4d, a left shift was observed up to ∼40-fold at 1.8 μM in the acetylcholine dose–response curve, indicating that 4d is a potent positive allosteric modulator of human M1 receptor. It worth noting that PAM 4d displayed dose-dependent partial agonism as indicated by an upward shift of acetylcholine dose–response curves at the two highest concentrations tested.

Figure 2.

Fold potentiation of 4d. Mean values from four replicate wells are plotted; data are representative of 12 independent experiments.

To evaluate the in vivo efficacy, PAM 4d was tested in a mouse contextual fear conditioning (CFC) assay, which serves as a model of episodic memory (Figure 3). In this study, mice were treated with scopolamine, a nonselective muscarinic antagonist, prior to exposure to a novel environment to impair a new association. Mice dosed by intrapertitoneal injection with 4d exhibited a significant reversal of scopolamine-induced deficit at 1 mpk relative to mice treated with scopolamine alone. The corresponding plasma level at 1 mpk was 1.5 μM. By way of comparison, the previous lead, carboxylic acid 2 showed significant reversal at ∼1 μM plasma levels. The result demonstrated robust proof-of-action for the new series despite the fact that lactam 4d is a rodent P-gp substrate. Pharmacokinetics of lead compound 4d was also evaluated in rat and dog (Table 4). Low clearance was observed in these two species, further highlighting the potential to provide potent M1 PAMs with potential for good human pharmacokinetic properties.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of lactam 4d in the mouse CFC model. Data are representative of four experiments. *, Different from vehicle; #, different from scopolamine + vehicle (P < 0.05, Dunnet test).

Table 4. Pharmacokinetics of 4d in Rat and Dog.

| dose (mg/kg) | route | Cl (min/ml/kg) | Vdss (L/kg) | T1/2 (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rat | 2 | iv | 4.1 | 2.8 | 12 |

| dog | 0.125 | iv | 2.1 | 1.2 | 6.7 |

In summary, naphthyl-fused 5-membered lactams have emerged as a new class of M1 positive allosteric modulators. This naphthyl fused lactam is novel not only because it shows that cyclization of the amide in 3 into a lactam is tolerated but that the quinolizidinone can be replaced by the naphthalene meaning that the carbonyl moiety present in previous quinolone and quinolizidinone M1 PAMs is not required for activity. The trans-1S,2S-2-hydroxy cyclohexyl group was found to be the most potent group off the amide position, and significant attenuation of P-gp efflux could be garnered. Compound 4d demonstrated high CSF drug levels and good efficacy in a mouse contextual fear model of episodic memory despite being a rodent P-gp substrate. Further SAR study of these lactams with respect to improving solubility at neutral pH and reducing P-gp efflux is expected to provide optimized M1 PAMs and will be reported in due course.

Supporting Information Available

Representative assay and experimental procedures and data for test compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Geula C. Abnormalities of neural circuitry in Alzheimer’s disease: hippocampus and cortical innervation. Neurology 1998, 51, 518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner T. I. The molecular basis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor diversity. Trends Neurosci. 1989, 12, 148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner T. I. Subtypes of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989, 11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey A. I. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression in memory circuits: Implications for treatment of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 13451–13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J.; Christopulos A.; Lindsley C. W. Allosteric modulators of GPCRs: a novel approach for the treatment of CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example of an allosteric activator of the M1 receptor, seeJones C. K.; Brady A. E.; Davis A. A.; Xiang Z.; Bubser M.; Noor-Wantawy M.; Kane A. S.; Bridges T. M.; Kennedy J. P.; Bradley S. R.; Peterson T. E.; Ansari M. S.; Baldwin R. M.; Kessler R. M.; Deutch A. Y.; Lah J. J.; Levey A. I.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J. Novel selective allosteric activator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulates amyloid processing and produces antipsychotic-like activity in rats. J. Neurosci. 2008, 41, 10422–10433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Beshore D. C. Novel M1 allosteric ligands: a patent review. Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012, 22, 1385–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie B. J.; Christopoulos A.; Scammells P. J. Development of M1 mAChR allosteric and bitopic ligands: therapeutics for the treatment of cognitive deficits. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1026–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Seager M.; Wittmann M.; Jacobsen M.; Bickel D.; Burno M.; Jones K.; Kuzmick-Graufelds V.; Xu G.; Pearson M.; McCampbell A.; Gaspar R.; Shughrue P.; Danziger A.; Regan C.; Flick R.; Garson S.; Doran S.; Kreatsoulas C.; Veng L.; Lindsley C.; Shipe W.; Kuduk S. D.; Sur C.; Kinney G.; Seabrook G.; Ray W. J. Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allosteric potentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 15950–19555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F. V.; Shipe W. D.; Bunda J. L.; Wisnoski D. D.; Zhao Z.; Lindsley C. W.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M. W.; Koeplinger K.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D. Parallel synthesis of N-biaryl quinolone carboxylic acids as selective M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Cofre V.; Pitts D. R.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Pyridine containing M1 positive allosteric modulators with reduced plasma protein binding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Cofre V.; Pitts D. R.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. N-Heterocyclic Derived M1 Positive Allosteric Modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 1334–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Chang R. K.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Heterocyclic fused pyridone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 2533–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; DiPardo R. M.; Beshore D. C.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Hydroxy cycloalkyl fused pyridone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 2538–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Identification of quinolizidinone carboxylic acids as CNS penetrant, selective M1 allosteric muscarinic receptor modulators. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 263–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Quinolizidinone carboxylic acid selective M1 allosteric modulators: SAR in the piperidine series. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1710–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Pitts D. R.; Greshock T. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T.; Ray W. J. Discovery of a selective allosteric M1 receptor modulator with suitable development properties based on a quinolizidinone carboxylic acid scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 4773–4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of noncarboxylic positive allosteric M1 modulators, seeShirey J. K.; Brady A. E.; Jones P. J.; Davis A. A.; Bridges T. M.; Kennedy J. P.; Jadhav S. B.; Menon U. N.; Xiang Z.; Watson M. L.; Christian E. P.; Doherty J. J.; Quirk M. C.; Snyder D. H.; Lah J. J.; Nicolle M. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J. A selective allosteric potentiator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor increases activity of medial prefrontal cortical neurons and restores impairments in reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 2009, 45, 14271–14286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Greshock T. J.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Identification of amides as carboxylic acid surrogates for quinolizilinone-based M1 positive allosteric modulators. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 1070–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock S. A. Structural modifications that alter the P-glycopprotein efflux properties of compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4877–4895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.