Abstract

Substituting a carbon atom with a nitrogen atom (nitrogen substitution) on an aromatic ring in our leads 11a and 13g by applying nitrogen scanning afforded a set of compounds that improved not only the solubility but also the metabolic stability. The impact after nitrogen substitution on interactions between a derivative and its on- and off-target proteins (Raf/MEK, CYPs, and hERG channel) was also detected, most of them contributing to weaker interactions. After identifying the positions that kept inhibitory activity on HCT116 cell growth and Raf/MEK, compound 1 (CH5126766/RO5126766) was selected as a clinical compound. A phase I clinical trial is ongoing for solid cancers.

Keywords: Nitrogen scan, Raf, MEK, kinase inhibitor, CH5126766, RO5126766

In the hit-to-lead process in medicinal chemistry, critical aspects in a compound are compatibility between the physicochemical properties, safety profiles, and bioactivity. However, a derivatization favorable for one factor (bioactivity, physicochemical properties, toxicity, etc.) often means that another factor fails the criteria set for its advancement to the clinic. To solve this paradox, one could attempt to improve one factor by using a chemical modification that minimally changes the conformation of a lead because the impact on other factors might be minimized. A fluorine atom substitution of a hydrogen atom attached to a carbon atom (fluorine substitution) is a representative example of such derivatization: when subsets of neighboring functional groups to the introduced fluorine are absent, changes in 3D conformation would be minimal compared to other modifications, and those of electronic properties would also be limited.1−5

Another approach is nitrogen substitution of aromatic moieties.6−8 In nitrogen substitution, just as in fluorine substitution, 3D conformational changes of a lead compound could be smaller than other possible chemical modifications, if no critical functional groups that cause electronic repulsions or interactions are located in proximity to the introduced nitrogen. In contrast to fluorine substitution, nitrogen substitution derives inherently dramatic changes in the electronic properties.

Reflecting its ability to make such changes in electronic properties, nitrogen substitution has been utilized to modify various physicochemical properties and safety profiles. Improved water solubility has been reported,9 with benefits to the resulting PK profile.7 Decreasing hERG inhibitory activity of lipophilic leads10−12 was found using nitrogen substitution of a benzene moiety.13,14 Because CH−π interaction between a drug and the hERG channel are reported to be key regardless of the CLogP values,15 nitrogen substitution of a phenyl ring could also be effective from this point of view. Effects on CYP interactions by nitrogen substitutions are still being elucidated: pyridine moiety has the potential to inhibit CYP by the interaction of the nitrogen to Fe,16,17 while a report showed a compound after nitrogen substitution had reduced CYP inhibition compared to the parent.6 Metabolic stability was improved in derivatives by nitrogen substitution of aromatic moieties,8 which made them less susceptible to oxidative metabolism and also less lipophilic.

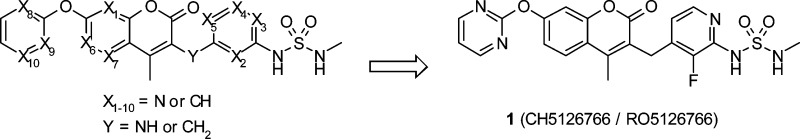

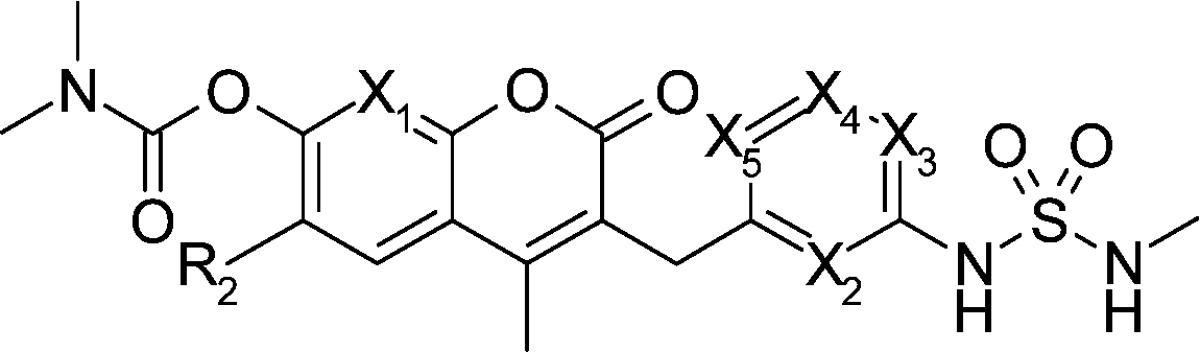

We recently reported SAR studies of a Raf and MEK inhibitor2,18 that inhibits one of the most important signal transduction pathways in human cancer, the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway.19 Introducing a sulfamide moiety to our coumarin hit afforded the compatibility of Raf/MEK activity and oral bioavailability.18 Fluorine scanning allowed us to identify better leads;2 because all the derivatives retained the physicochemical properties, we focused on identifying the positions for enhancing Raf/MEK activity (Scheme 1). Here we report another strategy, a nitrogen scan, in which conformational change of a lead would be smaller than other possible chemical modifications (C–H → C–NH2, CH → C–OH, etc.). Nitrogen-substituted compounds of our leads 11a and 13g, which had room for improved solubility and metabolic stability, afforded positive effects on them, regardless of the nitrogen substitution positions (Scheme 1). This allowed us to focus on finding the positions that kept bioactivity, and we identified the clinical compound 1 (CH5126766/RO5126766), which showed superior antitumor effects compared to a pure MEK inhibitor in a mouse xenograft.20

Scheme 1. Fluorine Scanning and Nitrogen Scanning Led to Clinical Compound 1.

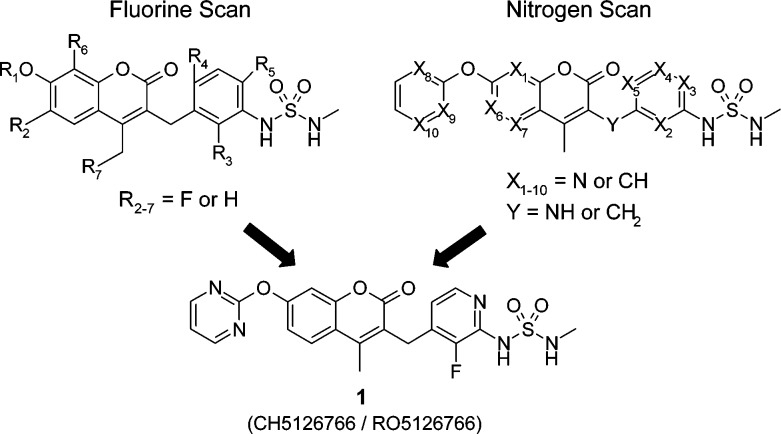

A set of coumarin derivatives possessing nitrogens (compounds 1, 11–13, and 15) was synthesized as shown in Scheme 2. Coumarin with nitrogen substituted at X2–X5 or Y was synthesized effectively in a manner similar to that reported previously.21 Compounds 4c–f, which were obtained by the alkylation of ethyl acetoacetate with bromomethylpyridines 3c–f, were converted to coumarins 6c–f via a typical Pechmann reaction with resorcinol 5a or 5f. After introducing the R1 moiety, reaction with N-methylsulfamoyl chloride or N-methyl-2-oxooxazolidine-3-sulfonamide afforded the targets 11b–e or 12f. The fluorinated compound 4g (X2 = CF), which was obtained by the alkylation of ethyl acetoacetate with compound 3g, was converted to target 1 or 13h–i, as above. A coumarin substituted to nitrogen at the Y position was also obtained via Pechmann reaction of resorcinol (5a) and compound 4j, which was prepared from the reaction of 3-nitroaniline (3j) with compound 9(22) and subsequent hydrolysis. Converting to the target 11j was smoothly achieved by reducing the nitro group and by subsequent sulfamoylation. In the case of the phenyl group at R1, coumarin was formed by the reaction of compound 5g instead of resorcinol (5a). Using Zn(OTf)2 in MeOH for the Pechmann reaction instead of H2SO4 was crucial for obtaining coumarin 6b, which has nitrogen at X1.23 Synthesis of 5- (X6 = N) or 6-azacoumarin (X7 = N) derivative was unsuccessful. An attempted Pechmann reaction using a typical condition (H2SO4) or modified conditions24 (NH2SO3H, ZrCl4, ZnCl2, Sm(NO3)3, and AlCl3) did not give the desired coumarin.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Coumarins 1, 11–13, and 15.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (Boc)2O, 60 °C, then (Boc)2O, THF, DMAP, rt; (b) NBS, benzoylperoxide or AIBN, CCl4, reflux; (c) ethyl acetoacetate, NaH, THF, 0 °C; (d) 5, conc. H2SO4; (e) LDA, THF, DMF, −78 to 0 °C, then NaBH4, 0 °C, 58%; (f) TBSCl, imidazole, THF, rt, 93%; (g) benzophenone imine, NaOtBu, Pd2(dba)3, rac-BINAP, toluene, 60 °C; (h) TBAF, THF, 76% (2 steps); (i) MsCl, LiOtBu, THF, 0 °C, then ethyl acetoacetate, LiOtBu, NaI, THF, 50 °C, 3 h, 95%; (j) 5a, MsOH, CF3CH2OH; (k) 9, THF, 70 °C, 12 h, 78%; (l) TiCl3, 20–30% HCl aq., acetone, rt, 30 min, 71%; (m) SnCl2·2H2O, EtOAc, 75 °C; (n) R1X, Cs2CO3 or K2CO3 or NaH, DMF; (o) R1X, CuI, N,N’-dimethylethylenediamine, Cs2CO3, DMF, 100 °C; (p) N-methylsulfamoyl chloride, pyridine, DMF; (q) N-methyl-2-oxooxazolidine-3-sulfonamide, Et3N, MeCN, 80 °C; (r) 5b, Zn(OTf)2, MeOH, reflux; (s) NaOH or KOH, MeOH.

In the five compounds in Table 1 with nitrogen substituted at different positions, only one position (X3) maintained inhibitory activity on HCT116 cell growth and Raf/MEK (compound 11d), and none of the positions enhanced it. Introducing nitrogen at X2 position resulted in decreased cell growth inhibitory activity by a factor of 10 (compound 11c) compared with the parent 11a. Compounds with a nitrogen substitution at X1, X4, and X5 showed larger than 50-fold decreases in cell growth inhibitory activity.

Table 1. Enzymatic and Cellular Activity and Pharmaceutical Properties of Coumarin Derivatives.

| IC50 (nM) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R2 | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | HCT116 | HT-29 | C-Raf | MEK1 | solubility (μg/mL) | CLint human (μL/min/mg) | PAMPA (10–6 cm/s) | AUC poa (μM·h) |

| 11a | H | CH | CH | CH | CH | CH | 24 | 9 | 300 | 110 | 32 | 20 | 6 | 78b |

| 11b | H | N | CH | CH | CH | CH | 1100 | 600 | 2500 | 440 | 43 | 3 | 3 | ND |

| 11c | H | CH | N | CH | CH | CH | 270 | 73 | 70 | 110 | 320 | 7 | 6 | 314 |

| 11d | H | CH | CH | N | CH | CH | 32 | 25 | 32 | 99 | 55 | 6 | 7 | 134 |

| 11e | H | CH | CH | CH | N | CH | >10000 | >10000 | >50000 | >50000 | 240 | ND | ND | ND |

| 12a | Me | CH | CH | CH | CH | CH | 22 | 8 | 78 | 29 | 11 | 17 | 4 | 18 |

| 12f | Me | CH | CH | CH | CH | N | >10000 | 5700 | 27000 | 37000 | 425 | ND | ND | ND |

Compounds were evaluated in 24 h exposure studies in mice at 100 mg/kg and formulated as solutions of 5% DMSO, 5% Cremophor EL, 15% PEG400, 15% HPCD, and 60% water.

Sodium salt was used.

On the other hand, all the evaluated compounds had improved water solubility and metabolic stability compared with the parent 11a or 12a (Table 1). Solubility was evaluated by the LYSA method (high-throughput solubility assay),25 and the values of the compounds 11b and 11d were slightly more than that of 11a, and those of 11c, 11e, and 12f increased up to 40-fold. Metabolic stability was evaluated using human liver microsome, and all evaluated compounds were more stable (by more than 3-fold) than the parent 11a. Because one of the metabolic positions of compound 11a was previously identified as the phenyl ring bearing a sulfamide moiety,18 decreasing the electron density of carbon atoms by replacing the aryl ring with a pyridyl ring (11c and 11d) would be a reason for oxidative metabolism to persist. Membrane permeability evaluated by the PAMPA method26 had high enough and comparable values to parent 11a. After oral administration of compound 11c or 11d to mice, AUCs increased up to 4-fold, which could reflect the improved metabolic stability and/or solubility.

We also modified the X8–10 (R1 part of Scheme 2) and Y part because modifying the carbamate part (R1 part), which is a major metabolic site, seemed fruitful (Table 2).18 Although the carbamate moiety was key for the strong bioactivity in our preliminary SAR,18 we obtained compound 13g (R1 = Ph) with acceptable cell inhibitory activity (IC50 = 110 nM in HCT116 cell line) after random modification of the R1 part by fixing R3 to fluorine2 and X3 to nitrogen. Because the solubility as evaluated by the LYSA method was lower (18 μg/mL), nitrogen scanning at the R1 position was performed. Compared to the parent compound 13g, compound 13h with nitrogen at X8 position maintained the inhibitory activity on HCT116 cell growth and Raf/MEK. Although introducing an additional nitrogen at X10 position caused weaker inhibitory activity on cell growth (compound 13i), introducing one at X9 position (compound 1(20)) afforded similar bioactivity to the parent 13g. Introducing nitrogen at the Y position derived almost no bioactivity (compound 15j). Nitrogen substitution improved solubility, and a high-throughput solubility assay of compounds 13g and 1 showed 18 and 159 μg/mL, respectively. The AUC of compound 1 after oral administration to mice increased 36-fold (2831 μM·h) compared to the original 11a. As just described, we succeeded in replacing a carbamate with a pyrimidyl moiety that was more metabolically stable. The effect of nitrogen substitution was also observed when the properties of compound 1 were compared to compound 14,2 which has C–H group at X3 and nitrogen at X8 and X9. Metabolic stability (1, 0.5 μL/min/mg; 14, 6.7 μL/min/mg), solubility (1, 159 μg/mL; 14, 13 μg/mL), and AUC (1, 2831 μM·h; 14, 425 μM·h) of compound 1 were all superior to those of compound 14 by around a factor of 10. As a result, by nitrogen scans at four additional positions (X8, X9, X10, and Y), we identified the promising compound 1, which has an IC50 value of 40 nM on HCT116 cell growth inhibitory activity and excellent solubility and AUC in mouse.

Table 2. Enzymatic and Cellular Activity of Coumarin Derivatives.

| IC50 (nM) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | X3 | X8 | X9 | X10 | Y | R3 | HCT116 | C-Raf | MEK1 |

| 13g | N | CH | CH | CH | CH2 | F | 110 | 21 | 76 |

| 13h | N | N | CH | CH | CH2 | F | 45 | 81 | 190 |

| 13i | N | N | CH | N | CH2 | F | 900 | 56 | 650 |

| 1 | N | N | N | CH | CH2 | F | 40 | 56 | 160 |

| 14 | CH | N | N | CH | CH2 | F | 17 | 23 | 97 |

| 15j | CH | N | N | CH | NH | H | >10000 | >50000 | >50000 |

CYP or hERG inhibitory activity in the nitrogen-introduced derivatives was superior to that of the corresponding parents (Table 3). Nitrogen-introduced derivative 11d showed almost no inhibition on CYP 2C9 and 3A4, while the parent 11a showed CYP 3A4 inhibition at an IC50 of 13 μM. This tendency is similar to a previous report,6 while pyridine moiety itself has the potential to inhibit CYP. One possible explanation is that reducing lipophilicity of the molecule and/or decreasing electron density of carbon atoms on an aromatic ring by nitrogen substitution might be key to reducing the interaction to CYPs, which inherently have the function of modifying lipophilic compounds to hydrophilic compounds.27−29 The same tendency was observed when comparing compounds 1 and 14.

Table 3. CYP and hERG Inhibition of Coumarin.

| CYP inhibition

IC50 (μM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| compd | 2C9 (−/+) | 3A4 (−/+) | hERG inhibitonb (%) |

| 11a | 29/96 | 13/5.6 | ND |

| 11d | >100/>100 | >100/>100 | ND |

| 14 | 19/19 | 26/11 | 25 |

| 1 | 12/60 | >100/>100 | no inhibition |

IC50 (−) and IC50 (+) values were determined after a 30 min preincubation without and with NADPH, respectively.

At 10 μM.

Our nitrogen scan at nine different positions resulted in us identifying three positions that kept bioactivity (Raf/MEK), six positions that decreased bioactivity at least 8-fold (Tables 1 and 2), and none that enhanced bioactivity. Because of the change in electronic structure to a more hydrophilic compound, derivatives after nitrogen substitution improved metabolic stability as well as solubility. The key to obtaining candidates with improved physicochemical properties is to identify the positions for nitrogen substitution at which the bioactivity will be acceptable. Decreased bioactivity could be explained by two possible reasons: reason 1 is that change of the whole 3D conformation after nitrogen substitution is critical and the compound could not achieve an active conformation; reason 2 is that change of the whole 3D conformation is minimal but electrostatic repulsion between the introduced nitrogen atom and target proteins is critical.

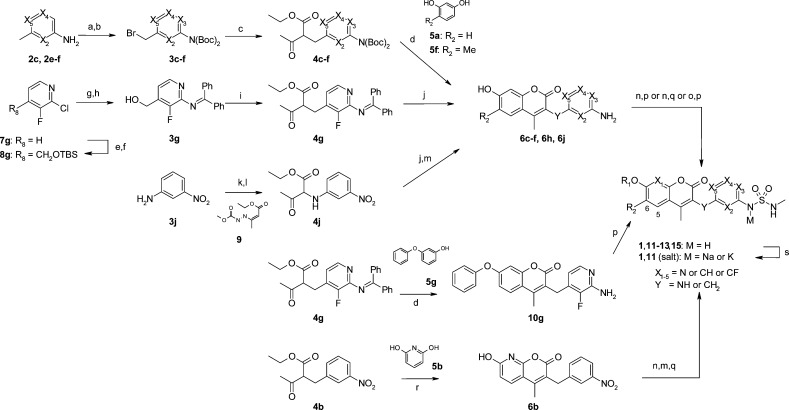

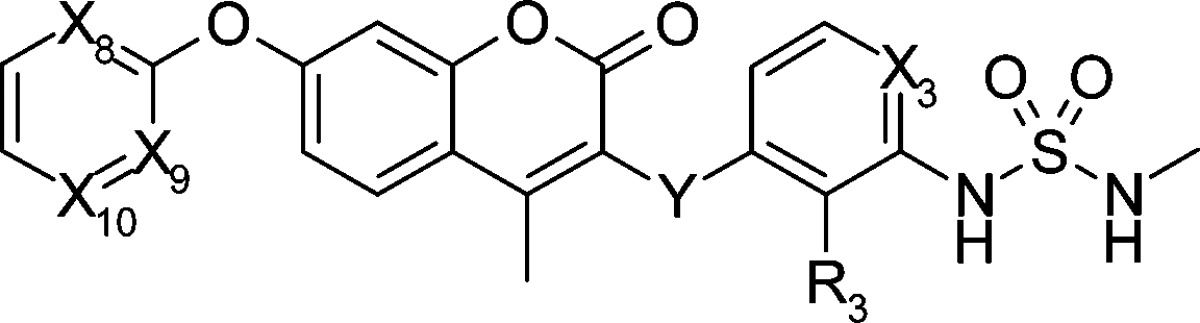

The effect on dihedral angles (ϕ1–ϕ6) was estimated by collecting crystal structures in the CSD data or by evaluation of potential energy surfaces at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level (Figure 1A). Crystal data processing a diaryl ether part in CSD showed that stable conformations after nitrogen substitution at X8 (blue), X9 (green), and X10 (red) overlapped well with those of the parent (black), and they had strong preferences for twisted structures (ϕ1 on 0°, 180°, and 360° and ϕ2 on 90° and 270° (Figure 1C)). Because lone pairs of N and O atoms were repulsive, conformations of the parent except those mentioned above could not be achieved (Figure S1 in Supporting Information).30 Similarly, potential energy surfaces of N-substituted compounds at X2 or X5 suggested its stable conformation overlapped with that of the parent (around ϕ3 on 90°, and ϕ4 on 240°), but they could not take another conformation because of N to O (carbonyl) repulsion (around ϕ3 on 90°, and ϕ4 on 60°; Figure 1B and Supporting Information Figure S5). The same tendency was observed at X1 of ϕ1–ϕ2 (see Supporting Information for calculated data of this and other values below). Structural difference for ϕ3–ϕ4 at X3 or X4 could be minimal. Fixation of sulfamide by intramolecular hydrogen bonding was suggested in ϕ5–ϕ6 at X2 or X3 by potential energy surfaces (Supporting Information Figure S6), while there were smaller effects at X4 or X5. Thus, two positions (X10 and X4) could afford smaller effects on the whole 3D structure (most preferred conformations of the parent would be acceptable), and the reason for their reduced bioactivity would be attributed to reason 2. Compounds after nitrogen substitution of six positions (X1, X2, X3, X5, X8, and X9) could inherit some stable conformations of the parent, but not others, because of intramolecular electrostatic repulsion and/or formation of hydrogen bonds. Three of them (X3, X8, and X9) retained bioactivity, and the other three reduced it (though the reason for reduced bioactivity could not be identified). We considered that our nitrogen scanning worked because at least some stable conformations could overlap with the parent in most derivatives after nitrogen substitution.

Figure 1.

(A) Rotatable bonds of our compound. (B) Potential energy surfaces calculated at the B3LYP/6-31(d) level. The ΔE from 0 to 5 kJ/mol is colored in blue, 5–10 kJ/mol in green, 10–15 kJ/mol in brown, and >15 kJ/mol in red. (C) Torsional distributions in small molecule crystal structures from the CSD data (* = C–R or N).

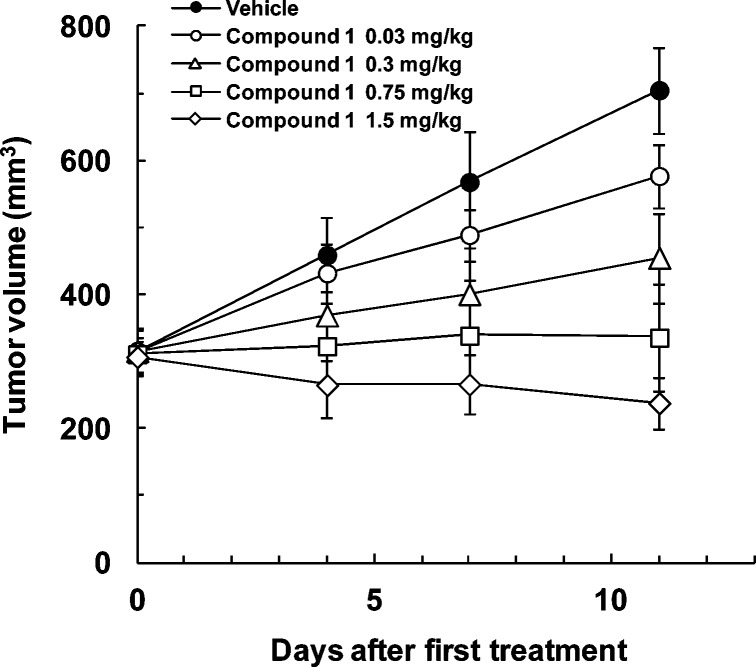

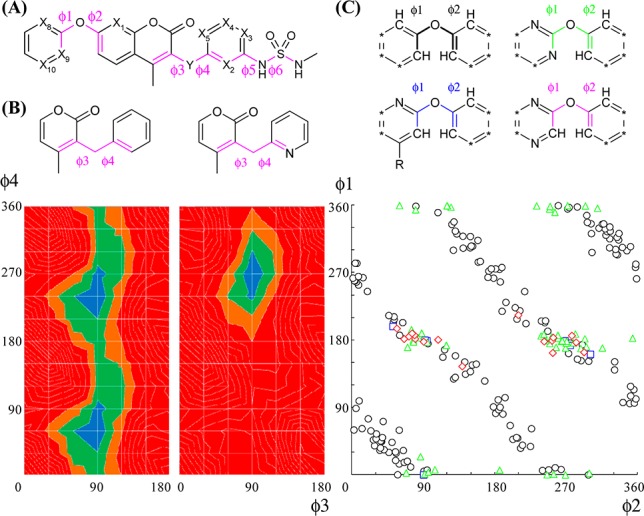

After further development of compounds 1(20) and 14(2) by pharmacology and PK profiles, we selected compound 1 for clinical trial. Compound 1 showed excellent PK data for mouse, rat, and monkey with bioavailability values comparable to compound 14 (compound 1, 93%, 66%, and 82%, and 14, 75%, 84%, and 59%, respectively) and better clearance values (compound 1, 1.1, 0.7, and 0.1 mL/min/kg, and 14, 6.8, 6.6, and 0.9 mL/min/kg, respectively). A potent antitumor effect of both compounds was observed in the C32 xenograft model (IC50s on C32 (B-Raf V600E) cell growth of compound 1, 47 nM, and 14, 57 nM): comparable maximum efficacy (TGI of compound 1, 118%; 14, 96%) and 16-fold smaller doses in compound 1 (ED50 of compound 1, 0.09 mg/kg, and 14, 1.44 mg/kg), which reflected the improvement in metabolic stability after nitrogen substitution (Figure 2 and Supporting Information). Neither compound showed serious effects on body weight or any adverse clinical signs.

Figure 2.

In vivo efficacy of 1 (K salt) in the C32 human malignant melanoma xenograft model. C32 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the right flank of BALB-nu/nu mice. Tumors were allowed to establish growth after implantation before start of treatment. Coumarin 1 was administered orally once daily for 11 days, from day 0 to day 10. Tumor size was measured twice per week. Values are mean ± SD, n = 4.

Salt screening was executed to identify the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), and crystalline K salts from compound 1 and 14 were found as the candidates.31 The supersaturated solubility of the K salt of compound 1 in fasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) after 4 h in a nonsink condition using a mini-scale dissolution test afforded 5-fold greater value (57 μg/mL) than that of compound 14 (12 μg/mL).32 However, nitrogen substituted compound 1 has comparable saturated solubility to the corresponding 14 regarding crystalline acids (free form). The saturated solubility of compounds 1 and 14 was determined after 24 h equilibration in FaSSIF, which gave 2.7 and 5.5 μg/mL, respectively.33 It is interesting that nitrogen substitution does not always contribute to increasing the saturated solubility in the free crystalline form; however, it still has an advantage for drug absorption in human because it contributes to increasing the ability to generate and keep the supersaturated state. Judging from these experiments, we selected the salt form of compound 1 (CH5126766/RO5126766)20 for clinical trial.

In summary, lead optimization of our leads 11a and 13g by nitrogen scanning at nine different positions worked effectively to improve the physicochemical properties such as metabolic stability and solubility, as evaluated by high-throughput assay. Changes by nitrogen substitution on the interactions between a derivative and its on- and off-target proteins (Raf/MEK, CYPs, and hERG channel) have an impact, and we focused on identifying the positions for maintaining Raf/MEK activity. Changes in electronic structure created synthetic difficulties because of the difference in reactivity of each nitrogen-containing building block. A candidate with nitrogen introduced could have an advantage in drug absorption, especially if supersaturated formulations, including a salt formation, were developed. We have demonstrated that, in late stage lead optimization, not only the fluorine scan but also the nitrogen scan worked efficiently to select the best compound for clinical use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Tachibana-Kondoh, K. Sakata, and T. Fujii for biological assays, Y. Ishiguro and H. Suda for mass spectrometry measurement, and Chugai Editing Services for proofreading the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AIBN

2,2′-azodiisobutyronitrile

- AUC

area under the curve

- BINAP

2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl

- CL

clearance

- CSD

Cambridge Structural Database

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- dba

dibenzylideneacetone

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- hERG

human ether-a-go-go related gene

- HPCD

2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- LYSA

lyophilized solubility assay

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced)

- NBS

N-bromosuccinimide

- ND

no data

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- TBAF

tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition

Supporting Information Available

Experimental preparation of compounds, characterization, biological data, in vitro physicochemical properties, conformational analysis results, and in vivo experimental data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Due to a production error, this paper published ASAP on January 24, 2014 without its required corrections. The revised version was reposted on January 27, 2014.

Supplementary Material

References

- The effect of fluorine substitution could vary depending on the presence or absence of subsets of neighboring functional groups. See refs (2)–5 and references therein.

- Hyohdoh I.; Furuichi N.; Aoki T.; Itezono Y.; Shirai H.; Ozawa S.; Watanabe F.; Matsushita M.; Sakaitani M.; Ho P.-S.; Takanashi K.; Harada N.; Tomii Y.; Yoshinari K.; Ori K.; Tabo M.; Aoki Y.; Shimma N.; Iikura H. Fluorine scanning by non-selective fluorination: enhancing Raf/MEK inhibition while keeping physicochemical properties. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 1059–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K.; Faeh C.; Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann W. K. The many roles for fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4359–4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser S.; Moore P. R.; Swallow S.; Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Yin Z.; Zhang Z.; Bender J. A.; Yang Z.; Johnson G.; Yang Z.; Zadjura L. M.; D’Arienzo C. J.; DiGiugno Parker D.; Gesenberg C.; Yamanaka G. A.; Gong Y.-F.; Ho H.-T.; Fang H.; Zhou N.; McAuliffe B. V.; Eggers B. J.; Fan L.; Nowicka-Sans B.; Dicker I. B.; Gao Q.; Colonno R. J.; Lin P.-F.; Meanwell N. A.; Kadow J. F. Inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) attachment. 5. An evolution from indole to azaindoles leading to the discovery of 1-(4-benzoylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-(4,7-dimethoxy-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-c]pyridin-3-yl)ethane-1,2-dione (BMS-488043), a drug candidate that demonstrates antiviral activity in HIV-1-infected subjects. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7778–7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung Y.-S.; Coumar M. S.; Wu Y.-S.; Shiao H.-Y.; Chang J.-Y.; Liou J.-P.; Shukla P.; Chang C.-W.; Chang C.-Y.; Kuo C.-C.; Yeh T.-K.; Lin C.-Y.; Wu J.-S.; Wu S.-Y.; Liao C.-C.; Hsieh H.-P. Scaffold-hopping strategy: synthesis and biological evaluation of 5,6-fused bicyclic heteroaromatics to identify orally bioavailable anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3076–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington L. D.; Croghan M. D.; Sham K. K. C.; Pickrell A. J.; Harrington P. E.; Frohn M. J.; Lanman B. A.; Reed A. B.; Lee M. R.; Xu H.; McElvain M.; Xu Y.; Zhang X.; Fiorino M.; Horner M.; Morrison H. G.; Arnett H. A.; Fotsch C.; Tasker A. S.; Wong M.; Cee V. J. Quinolinone-based agonists of S1P1: Use of a N-scan SAR strategy to optimize in vitro and in vivo activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplantier A. J.; Becker S. L.; Bohanon M. J.; Borzilleri K. A.; Chrunyk B. A.; Downs J. T.; Hu L.-Y.; El-Kattan A.; James L. C.; Liu S.; Lu J.; Maklad N.; Mansour M. N.; Mente S.; Piotrowski M. A.; Sakya S. M.; Sheehan S.; Steyn S. J.; Strick C. A.; Williams V. A.; Zhang L. Discovery, SAR, and pharmacokinetics of a novel 3-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one series of potent d-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3576–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson C.; Moir E. M.; Rankovic Z.; Wishart G. Medicinal chemistry of hERG optimizations: highlights and hang-ups. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5029–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronov A. M. Ligand structural aspects of hERG channel blockade. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1113–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Improving drug candidates by design: a focus on physicochemical properties as a means of improving compound disposition and safety. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1420–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley M.; Hallett D. J.; Goodacre S.; Moyes C.; Crawforth J.; Sparey T. J.; Patel S.; Marwood R.; Patel S.; Thomas S.; Hitzel L.; O’Connor D.; Szeto N.; Castro J. L.; Hutson P. H.; MacLeod A. M. 3-(4-Fluoropiperidin-3-yl)-2-phenylindoles as high affinity, selective, and orally bioavailable h5-HT2A receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1603–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H. C.; Ding F.-X.; Wang S.; Deng Q.; Zhang X.; Chen Y.; Zhou G.; Xu S.; Chen H.-S.; Tong X.; Tong V.; Mitra K.; Kumar S.; Tsai C.; Stevenson A. S.; Pai L.-Y.; Alonso-Galicia M.; Chen X.; Soisson S. M.; Roy S.; Zhang B.; Tata J. R.; Berger J. P.; Colletti S. L. Discovery of a highly potent, selective, and bioavailable soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor with excellent ex vivo target engagement. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5009–5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.; Li M.; You Q. The interactions between hERG potassium channel and blockers. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlström M. M.; Zamora I. Characterization of type II ligands in CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1755–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach A. G.; Kidley N. J. Quantitatively interpreted enhanced inhibition of cytochrome P450s by heteroaromatic rings containing nitrogen. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2011, 51, 1048–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T.; Hyohdoh I.; Furuichi N.; Ozawa S.; Watanabe F.; Matsushita M.; Sakaitani M.; Ori K.; Takanashi K.; Harada N.; Tomii Y.; Tabo M.; Yoshinari K.; Aoki Y.; Shimma N.; Iikura H. The sulfamide moiety affords higher inhibitory activity and oral bioavailability to a series of coumarin dual selective RAF/MEK inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 6223–6227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friday B. B.; Adjei A. A. K-ras as a target for cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1756, 127–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N.; Harada N.; Joseph E. W.; Ohara K.; Miura T.; Sakamoto H.; Matsuda Y.; Tomii Y.; Tachibana-Kondo Y.; Iikura H.; Aoki T.; Shimma N.; Arisawa M.; Sowa Y.; Poulikakos P. I.; Rosen N.; Aoki Y.; Sakai T. Enhanced inhibition of ERK signaling by a novel allosteric MEK inhibitor, CH5126766, that suppresses feedback reactivation of RAF activity. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4050–4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.-F.; Chen M.; Wallace D.; Tith S.; Arrhenius T.; Kashiwagi H.; Ono Y.; Ishikawa A.; Sato H.; Kozono T.; Sato H.; Nadzan A. M. Discovery and structure–activity relationship of coumarin derivatives as TNF-α inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 2411–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz A. G.; Hagmann W. K. Synthesis of indole-2-carboxylic esters. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3391–3393. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins R. L.; Bliss D. E. Substituted coumarins and azacoumarins. Synthesis and fluorescent properties. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 1975–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar K. C.; Debnath P.; Roy B. Metal-catalyzed heterocyclization: formation of five- and six-membered oxygen heterocycles through carbon-oxygen bond forming reactions. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 2661–2728. [Google Scholar]

- Alsenz J.; Kansy M. High throughput solubility measurement in drug discovery and development. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2007, 59, 546–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansy M.; Senner F.; Gubernator K. Physicochemical high throughput screening: parallel artificial membrane permeation assay in the description of passive absorption processes. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 1007–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Some reports suggested that lipophilic compounds or aromatic moieties tend to inhibit CYP more strongly. See refs (12), (28), and (29).

- Gleeson M. P.; Davis A. M.; Chohan K. K.; Paine S. W.; Boyer S.; Gavaghan C. L.; Arnby C. H.; Kankkonen C.; Albertson N. Generation of in-silico cytochrome P450 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 inhibition QSAR models. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 559–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. F. V.; Lake B. G.; Dickins M. Quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSARs) in CYP3A4 inhibitors: The importance of lipophilic character and hydrogen bonding. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2006, 21, 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chein R.-J.; Corey E. J. Strong conformational preferences of heteroaromatic ethers and electron pair repulsion. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The sulfamide could form a salt easily (see ref (18)). The pKas of compound 1 and 14 were 7.02 and 8.86, respectively.

- Takano R.; Sugano K.; Higashida A.; Hayashi Y.; Machida M.; Aso Y.; Yamashita S. Oral absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs: computer simulation of fraction absorbed in humans from a miniscale dissolution test. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1144–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Our LYSA method measured the ability to keep a supersaturated state by dissolving concentrated DMSO solution of the compounds in water (see Supporting Information). In our lead optimization, we did not measure saturated solubility from a crystalline acid, which could correlate with the melting point.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.