Abstract

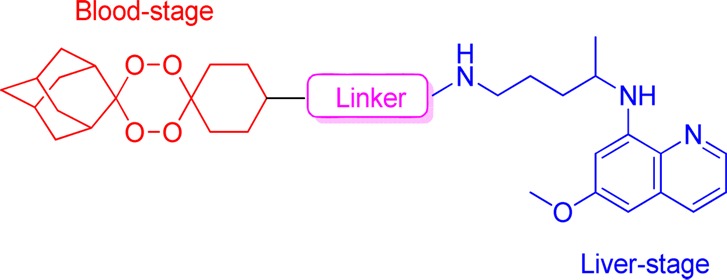

In a search for effective compounds against both the blood- and liver-stages of infection by malaria parasites with the ability to block the transmission of the disease to mosquito vectors, a series of hybrid compounds combining either a 1,2,4-trioxane or 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane and 8-aminoquinoline moieties were synthesized and screened for their antimalarial activity. These hybrid compounds showed high potency against both exoerythrocytic and erythrocytic forms of malaria parasites, comparable to representative trioxane-based counterparts. Furthermore, they efficiently blocked the development of the sporogonic cycle in the mosquito vector. The tetraoxane-based hybrid 5, containing an amide linker between the two moieties, effectively cleared a patent blood-stage P. berghei infection in mice after i.p. administration. Overall, these results indicate that peroxide-8-aminoquinoline hybrids are excellent starting points to develop an agent that conveys all the desired antimalarial multistage activities in a single chemical entity and, as such, with the potential to be used in malaria elimination campaigns.

Keywords: Antimalarials, endoperoxide, sporogonic cycle, P. berghei

Malaria is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by infection with parasites of the genus Plasmodium and transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.1 Among the five Plasmodium species that commonly infect humans, P. falciparum is responsible for most of the mortality worldwide.2 Parasite resistance to antimalarial drugs remains a real and ever-present danger. For this reason, the WHO recommends that P. falciparum malaria should be treated with artemisinin (ART, 1)-based combination therapies (ACT), in which the ART-based component is combined with a second, longer-acting agent.1,3 Artemisinin and its derivatives are potent blood schizontocides, acting rapidly against parasitic forms that invade erythrocytes and cause disease symptoms.4

The ultimate goal of eradicating malaria will benefit greatly from a drug that eliminates all life cycle stages of parasites.5 Malaria parasites undergo an asymptomatic, obligatory developmental phase in the liver, which precedes the formation of red blood cell-infective forms.6 Thus, the liver stage of infection offers important potential for disease prevention, as intervention at this stage acts before the onset of symptoms, providing a true causal prophylactic strategy.7 In addition, P. vivax, the second most prevalent species causing human malaria, and P. ovale infections can generate cryptic parasite forms called hypnozoites that persist in the liver for long periods of time and that, upon reactivation, are responsible for relapses of malaria.8 Thus, antiliver stage drugs would also be beneficial for a malaria eradication campaign through elimination of the long-lived hypnozoites of P. vivax and P. ovale in the liver.8,9 Primaquine (2, PQ, Chart 1) is the only drug currently used for the radical cure of P. vivax and P. ovale malaria and is active against the transient liver forms of all Plasmodium species. Moreover, PQ is also used as a gametocytocidal, i.e., it is active against the blood-circulating sexual forms of the parasite that are transmitted to the mosquito upon a blood meal, and in this way, it is able to block the transmission of infection from the human host to mosquito vectors.10,11 The liver and sporogonic stages of malaria parasites have remained largely underexploited as antimalarial targets due to the poorly understood biology of these life-cycle stages and the inherent technical difficulties in studying them.7,11 Only recently have systematic efforts toward the identification of novel liver schizontocidal and transmission blocking scaffolds been reported.4,12−14

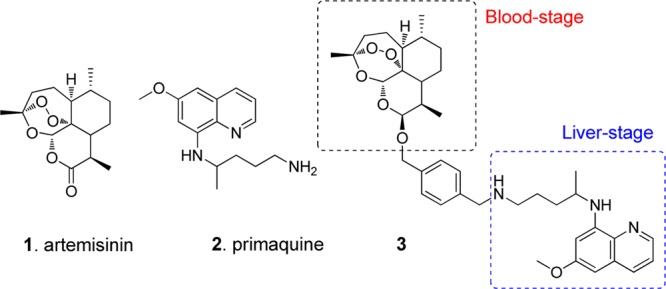

Chart 1. Structures of Arteminisin, 1, Primaquine, 2, and an Artemisinin–Primaquine Hybrid, 3.

Endoperoxide-based hybrid compounds represent an attractive alternative to ACTs.15−19 ART contains a 1,2,4-trioxane core that is reductively activated by iron(II) heme, a byproduct of host hemoglobin degradation, to form carbon-centered radicals capable of reacting with heme and proteins.20 An alternative model for the antimalarial mechanism of endoperoxides has been put forward by Haynes and Monti whereby endoperoxides mediate their antimalarial activity through interaction with cofactors. The tetraoxanes reported here are also likely to be capable of oxidizing cofactors such as FADH2 and differences in activity between trioxanes and tetraoxanes may reflect the different oxidizing capacities of the two heterocycles.21,22

We recently reported, for the first time, the ability of PQ-ART hybrid molecules, e.g., 3, to impair the liver and erythrocyte stages of Plasmodium, a result that paves the way for the exploitation of this approach for malaria control and eradication.23 We now extend this hybrid-based strategy to fully synthetic 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes, a class of peroxides with potent blood schizontocidal activity.24 The aims of this study were (i) to evaluate the efficacy of hybrid compounds 5, 8, 10, and 12 (Scheme 1) against Plasmodium liver and erythrocyte stages and compare their activities to those of their 1,2,4-trioxane counterparts 16 and 18 (Schemes 2 and 3), and (ii) to determine their potential as transmission-blocking agents.

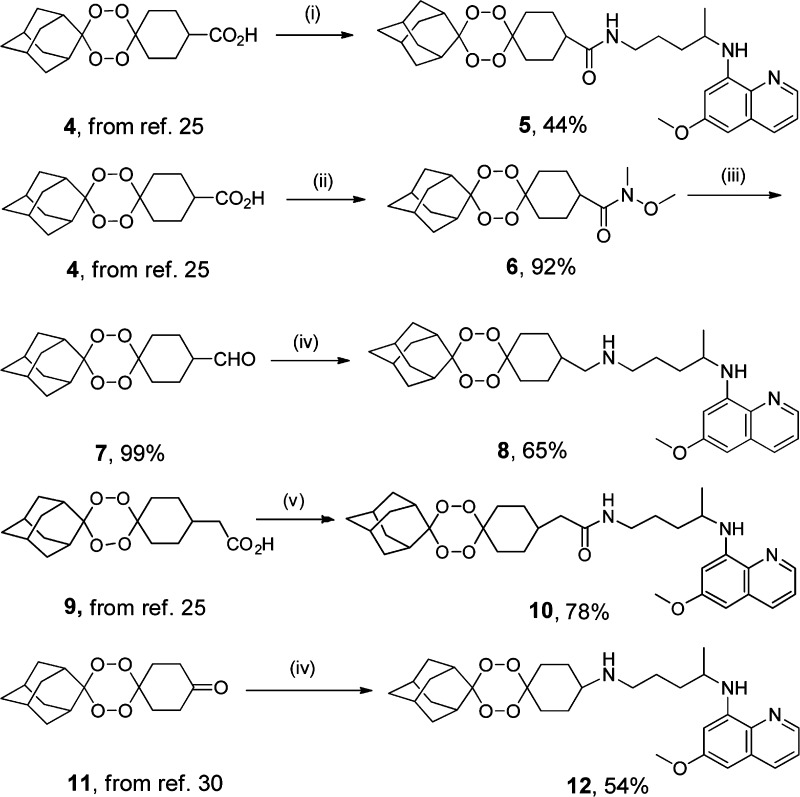

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Tetraoxane-Primaquine Hybrids.

Reagents and conditions: (i) a, TBTU, DCM, TEA, 0 °C, 1 h; b, PQ, DCM, TEA, rt. (ii) CH3NHOMe, TBTU, DCM, TEA, rt, 7 h. (iii) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C, 1 h. (iv) a, PQ, DCM, rt, 30 min; b, NaBH(AcO)3, AcOH, rt, 16 h. (v) a, CH3OCOCl, TEA, DCM, 0 °C 1 h; b PQ, 0 °C 30 min, rt, 1.5 h.

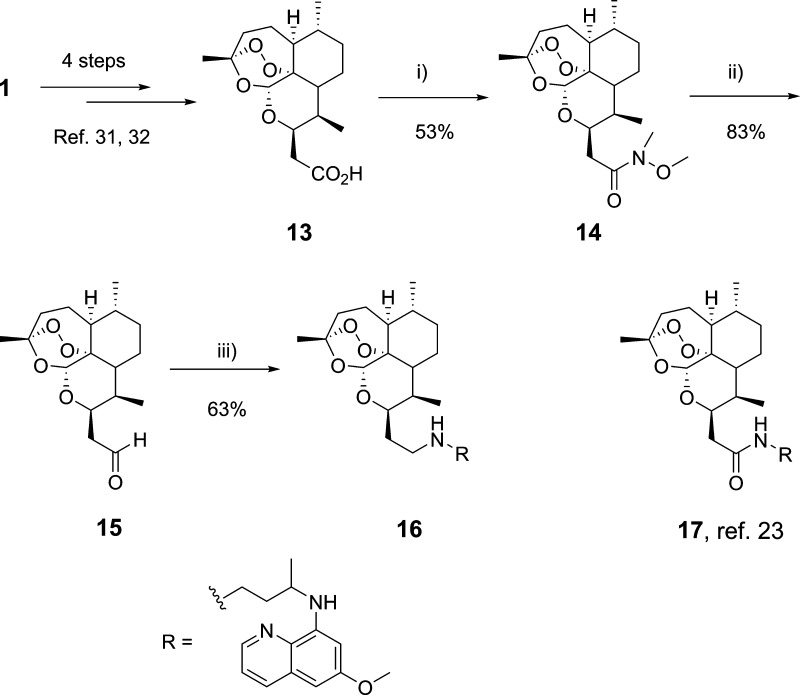

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Trioxane–Primaquine Hybrid 16 and Structure of Hybrid 17.

Reagents and conditions: (i) CH3NHOMe, TBTU, DCM, TEA, rt, 7 h. (ii) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C 2 h. (iii) a, PQ, DCM, rt, 30 min; b, NaBH(AcO)3, AcOH, rt.

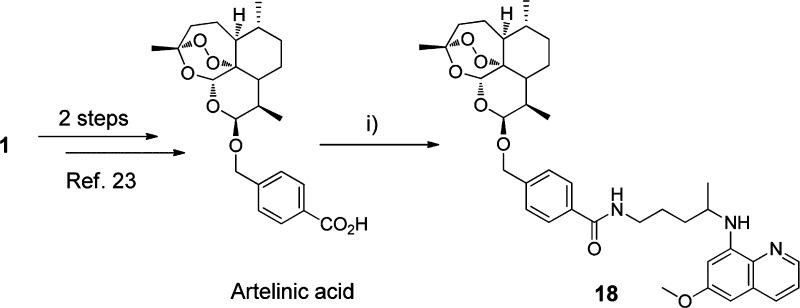

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Trioxane–Primaquine Hybrid 18.

Reagents and conditions: (i) a, TBTU, DCM, TEA, 0 °C, 1 h; b, PQ, DCM, TEA, rt.

The preparation of hybrid compounds 5, 8, 10, and 12 is outlined in Scheme 1. Compounds 5 and 10, containing an amide linker between the two pharmacophoric moieties, were synthesized by reacting tetraoxanes 4 and 9 with PQ, using TBTU and methyl chloroformate as coupling agents, respectively. Tetraoxanes 4 and 9 as starting materials were prepared via a rapid three-step synthesis that was previously reported.24−26

The synthesis of hybrid 8, the amine counterpart of 5, started with the conversion of tetraoxane 4 to the Weinreb amide 6, which was then reduced to the corresponding aldehyde 7 with LiAlH4.27−29 Reductive amination of 7 with PQ and NaBH(AcO)3 gave compound 5 in moderate yield. Hybrid 12 was synthesized by reductive amination of tetraoxane 11 with PQ and NaBH(AcO)3.30 The 1,2,4-trioxane-based hybrid 16, the amine counterpart of the previously reported amide 17, was prepared as outlined in Scheme 2.23 The synthetic pathway started with ART, which was converted to 10β-carboxymethyl-10-desoxy-dihydroartemisinin 13.31,32 Following the same procedure used for 6, compound 13 was converted to the Weinreb amide 14 and then reduced to the corresponding aldehyde 15 with LiAlH4. Reductive amination of 15 with PQ in acetic acid gave compound 16 in moderate yield. Finally, hybrid 18, the amide counterpart of 3, was prepared by reacting artelinic acid with PQ and TBTU.

Tetraoxanes 5, 8, 10, and 12 and semisynthetic trioxanes 16 and 18 were first screened for activity against the erythrocyte-stage of chloroquine-resistant W2-strain P. falciparum (Table 1). Compounds 5, 8, 10, and 12 inhibited the growth of parasites with IC50 values ranging from 21 to 45 nM, suggesting that the nature of the linker between the tetraoxane and PQ moieties does not significantly affect antiplasmodial activity. Trioxanes 16 and 18 were slightly more potent than tetraoxanes as antiplasmodial agents, with IC50 values of 9 and 5 nM, respectively (Table 1). These values are of the same order of magnitude as those reported for their counterparts 3, 17, and ART. As expected, PQ showed only modest activity in this assay.

Table 1. In Vitro Antimalarial Activity and Toxicity of Tetraoxanes 5, 8, 10, and 12 and Trioxanes 16–18.

| in vitro

activity (IC50/nM) |

cytotoxicity (IC50/μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| compd | blood-stagea | liver-stageb | Huh7 |

| 3 | 12.5c | 155c | ND |

| 5 | 21.1 | 538 | >100 |

| 8 | 45.2 | >1000 | 5.02 |

| 10 | 36.5 | 604 | 2.57 |

| 12 | 21.6 | 330 | 8.20 |

| 16 | 9.3 | >1000 | 32.8 |

| 17 | 9.1c | 523c | ND |

| 18 | 5.1 | 67 | 73.0 |

| 4, ethyl ester | 128.2 | NA | ND |

| PQ | 3300 | 7500 | ND |

| ART | 8.2 | NA | ND |

| PQ + ART | ND | 9714 | ND |

Determined against the chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum W2 strain.

Determined against P. berghei; ND, not determined; NA, not active (>10 μM).

Ref (23).

To evaluate the abilities of hybrids 5, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 18 to inhibit infection of liver cells by malaria parasites, the compounds were tested using an in vitro infection model that employs a human hepatoma cell line (Huh7) and the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei.7 Parasite load was assessed by bioluminescence measurements following infection with luciferase-expressing parasites, as previously described.33 The results were compared with those obtained for a tetraoxane lacking the 8-aminoquinoline moiety, the ethyl ester of 4 (Table 1). All hybrids showed high potency against the liver forms of the parasite, with most of the compounds displaying IC50 values in the low to mid nM range. In contrast, the parent tetraoxane showed to be inactive at 10 μM, suggesting that this scaffold is not intrinsically effective against the liver stages of the parasite. Furthermore, hybrids were significantly more potent than PQ and the 1:1 PQ–ART mixture. This is consistent with what has been previously reported for compounds 3 and 17.23 Additionally, none of the compounds significantly affected Huh7 cell proliferation, indicating that tetraoxane–PQ hybrids are selective and nontoxic antimalarial agents (Table 1).

Since PQ is known to undergo extensive oxidative deamination at the primary amine, the metabolic stability of tetraoxane-based hybrids 5 and 8 was evaluated in rat liver microsomes, at 37 °C. From the results presented in Table 2 it is possible to conclude that tetraoxane 5, containing an amide linker between the two pharmacophoric moieties, displayed a high rate of metabolism in rat liver microsomes and predicted in vivo hepatic extraction ratio, EH. In contrast, its amine counterpart 8 presented an intermediate EH values, suggesting that metabolic susceptibility of tetraoxane hybrids are affected by the nature of the linker between the two moieties. Neither primaquine nor its oxidative deamination product, carboxyprimaquine,10 were detected in the incubation mixtures, suggesting that other metabolic pathways might be operating for 5 and 8. In addition, these hybrids did not degrade when incubated in 80% human plasma for 3 days.

Table 2. In Vitro Metabolism of Compounds 5 and 8 in Rat Liver Microsomes and Predicted in Vivo Metabolism Data.

| compd | t1/2 (min) | CLint,invitro (μL/min/mg protein) | predicted EH | putative metabolitesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10 | 132.8 | 0.81 | Not detected |

| 8 | 27 | 51.2 | 0.62 | Not detected |

Primaquine and carboxyprimaquine.

Having determined the activity profile of tetraoxane-based hybrids against the blood- and liver-stage of infection, we then evaluated the in vivo antimalarial efficacy of compound 5 using GFP-expressing P. berghei ANKA-infected male C57Bl/6J mice. This compound was administered i.p. at 30 mg/kg dose once a day for 5 days. Parasitemias were monitored daily by microscopy and flow cytometry. Remarkably, compound 5 completely and irreversibly cleared the parasitemia by day 8 postinfection, and all treated animals survived until the end of the experiment, whereas all control mice succumbed with signs of experimental cerebral malaria at day 6 postinfection (Figure 1), clearly indicating that tetraoxane-based hybrids have curative value. Furthermore, no adverse reactions were observed following administration of 5 at the dosage regimen used in this study.

Figure 1.

In vivo mouse efficacy studies for compound 5 in the P. berghei mouse model. Mice were infected with parasites on day 0, and compound 5 dosing began on day 4 and lasted for a total of 5 consecutive days (indicated by the arrows). Dosing was by i.p. administration at 30 mg/kg b.w. (A) Parasitemia curve; (B) survival curve.

The potential of tetraoxane hybrids to inhibit the sporogonic cycle of the parasite within the mosquito was also evaluated using an established in vivo infection model consisting of BALB/c mice infected with P. berghei ANKA-GFP and Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes.34,35 In this model, mice infected with parasitised erythrocytes were treated by a single i.p. injection of each compound at two dose levels (10 and 25 μmol·kg–1). Two hours after administration, glucose-starved mosquitoes were allowed to feed on the anesthetized mice. The engorged mosquitoes were maintained at 19 ± 1 °C, for 10 days and then collected and dissected for microscopy detection of oocysts in midguts. The criteria used to assess the antimalarial activity of each compound were the percentage of mosquitoes with oocysts and the mean number of oocysts per infected mosquito, when compared to nontreated controls. Inspection of data presented in Table 3 shows that compounds 5, 8, 10, and 12 affected the development of the sporogonic cycle of P. berghei in A. gambiae mosquitoes at the dose levels of 10 and 25 μmol·kg–1. In particular, compound 5 was superior to PQ, and completely inhibited the appearance of oocysts in mosquito midguts when administered at 25 μmol·kg–1. Compounds 8, 10, and 12 also markedly decreased the percentage of infected mosquitoes as well as the number of oocysts at the highest dose tested. Although it should be noted that this in vivo model cannot specifically ascribe the drug effect to either gametocytocidal or sporontocidal activity, the results clearly show that hybrids 5, 8, 10, and 12 are effective at interrupting the transmission of malaria parasites to mosquitoes.

Table 3. Effect of Compounds 5, 8, 10, 12 and Primaquine on the Sporogonic Development of Plasmodium berghei ANKA in Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes.

| mean no.

oocysts per mosquito ± SEMa |

% infected

mosquitoes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | 10 μmol·kg–1 | 25 μmol·kg–1 | 10 μmol·kg–1 | 25 μmol·kg–1 |

| PQ | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 35.5 | 2.2 |

| 5 | 23.2 ± 5.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 68.6 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 8.0 ± 3.6 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 42.9 | 5.9 |

| 10 | 26.9 ± 6.1b | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 66.7 | 11.4 |

| 12 | 19.3 ± 8.0b | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 36.4 | 13.3 |

| control | 42.1 ± 4.4 | 83.6 | ||

Standard error of the mean.

Not significantly different from control (P < 0.05) using the Mann–Whitney test.

In conclusion, a new class of hybrid compounds combining endoperoxides and 8-aminoquinoline pharmacophores was developed to target both blood- and liver-stages of parasites and to block the transmission of infection to mosquito vectors. The in vitro antimalarial profile of these compounds reveals that they display potent inhibitory activity against the blood stage of infection, with IC50 values in the nanomolar range, a level of activity similar to that of artemisinin-based hybrid compounds. Screening against P. berghei liver stage of infection revealed that both the tetraoxane- and trioxane-based series are potent inhibitors of the exoerythrocytic forms of the parasite, with IC50 values in the submicromolar range, being superior to a 1:1 PQ–ART mixture.23 In vivo studies revealed that compound 5 irreversibly cleared the parasitemia from infected mice, while screening of transmission-blocking activity showed that the tetraoxanes show potent activity in reducing the percentage of infected mosquitoes and the mean number of oocysts per mosquito. These results indicate that these hybrids are excellent starting points to develop agents with the potential to be used in malaria eradication campaigns since they display all the desired antimalarial multistage activities.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. Virgílio do Rosário for helpful discussions on the transmission-blocking assays.

Supporting Information Available

General procedure and structural data for compounds 5–8, 10, 12, 14–16, and 18; in vitro and in vivo assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal: grants PTDC/SAU-FAR/118459/2010, Pest-OE/SAU/UI4013/2011, PTDC/SAU-MIC/117060/2010 (to M.P.), SFRH/BD/63200/2009 (to R.O.). M.M.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Scholar and P.J.R. is a Distinguished Clinical Scientist of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO. World Malaria Report 2011; Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Kantele A.; Jokiranta T. S. Review of cases with the emerging fifht human malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 1356–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli A.; Moreira R.; Cravo P. V. L Malaria combination therapies: Advantages and shortcomings. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delves M.; Plouffe D.; Scheurer C.; Meister S.; Wittlin S.; Winzeler E. A.; Sinden R. E.; Leroy D. The activities of current antimalarial drugs on the life cycle stages of plasmodium: A comparative study with human and rodent parasites. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A research agenda for Malaria eradication: Drugs. PloS Med. 2011, 8, e1000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio M.; Rodriguez A.; Mota M. M. The silent path to thousands of merozoites: the Plasmodium liver stage. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio M.; Mota M. M.; Mendes A. M. A toolbox to study liver stage malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2011, 27, 565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells T. N.; Burrows J. N.; Baird J. K. Targeting the hypnozoite reservoir of Plasmodium vivax: the hidden obstacle to malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2010, 26, 145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire E. R.; Mota M. M.; Clardy J. The next opportunity in anti-malaria drug discovery: the liver stage. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale N.; Moreira R.; Gomes P. Primaquine revisited six decades after its discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 443937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T.; Prudencio M.; Moreira R.; Mota M. M.; Lopes F. Targeting the liver stage of malaria parasites: A yet unmet goal. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 995–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S.; Plouffe D. M.; Kuhen K. L.; Bonamy G. M. C.; Wu T.; Barnes S. W.; Bopp S. E.; Borboa R.; Bright A. T.; Che J. W.; Cohen S.; Dharia N. V.; Gagaring K.; Gettayacamin M.; Gordon P.; Groessl T.; Kato N.; Lee M. C. S.; McNamara C. W.; Fidock D. A.; Nagle A.; Nam T. G.; Richmond W.; Roland J.; Rottmann M.; Zhou B.; Froissard P.; Glynne R. J.; Mazier D.; Sattabongkot J.; Schultz P. G.; Tuntland T.; Walker J. R.; Zhou Y. Y.; Chatterjee A.; Diagana T. T.; Winzeler E. A. Imaging of Plasmodium liver stages to drive next-generation antimalarial drug discovery. Science 2011, 334, 1372–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F. P.; Martin C.; Buchholz K.; Lafuente-Monasterio M. J.; Rodrigues T.; Sönnichsen B.; Moreira R.; Gamo F.-J.; Marti M.; Mota M. M.; Hannus M.; Prudêncio M. Drug screen targeted at Plasmodium liver stages identifies a potent multistage antimalarial drug. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 1278–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire E. R.; Prudencio M.; Mota M. M.; Clardy J. Liver-stage malaria parasites vulnerable to diverse chemical scaffolds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 8511–8516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh J. J.; Bell A. Hybrid drugs for Malaria. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2970–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill P. M.; Stocks P. A.; Pugh M. D.; Araujo N. C.; Korshin E. E.; Bickley J. F.; Ward S. A.; Bray P. G.; Pasini E.; Davies J.; Verissimo E.; Bachi M. D. Design and synthesis of endoperoxide antimalarial prodrug models. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4193–4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit-Vical F.; Lelievre J.; Berry A.; Deymier C.; Dechy-Cabaret O.; Cazelles J.; Loup C.; Robert A.; Magnaval J. F.; Meunier B. Trioxaquines are new antimalarial agents active on all erythrocytic forms, including gametocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1463–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosledan F.; Fraisse L.; Pellet A.; Guillou F.; Mordmuller B.; Kremsner P. G.; Moreno A.; Mazier D.; Maffrand J. P.; Meunier B. Selection of a trioxaquine as an antimalarial drug candidate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 17579–17584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo N. C. P.; Barton V.; Jones M.; Stocks P. A.; Ward S. A.; Davies J.; Bray P. G.; Shone A. E.; Cristiano M. L. S.; O’Neill P. M. Semi-synthetic and synthetic 1,2,4-trioxaquines and 1,2,4-trioxolaquines: synthesis, preliminary SAR and comparison with acridine endoperoxide conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2038–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill P. M.; Posner G. H. A medicinal chemistry perspective on artemisinin and related endoperoxides. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 2945–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. K.; Chan W. C.; Wong H. N.; Li K. Y.; Wu W. K.; Fan K. M.; Sung H. H. Y.; Williams I. D.; Prosperi D.; Melato S.; Coghi P.; Monti D. Facile oxidation of leucomethylene blue and dihydroflavins by artemisinins: Relationship with flavoenzyme function and antimalarial mechanism of action. ChemMedChem 2010, 5, 1282–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. K.; Cheu K. W.; Tang M. M. K.; Chen M. J.; Guo Z. F.; Guo Z. H.; Coghi P.; Monti D. Reactions of antimalarial peroxides with each of leucomethylene blue and dihydroflavins: Flavin reductase and the cofactor model exemplified. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capela R.; Cabal G. G.; Rosenthal P. J.; Gut J.; Mota M. M.; Moreira R.; Lopes F.; Prudêncio M. Design and evaluation of primaquine-artemisinin hybrids as a multistage antimalarial strategy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4698–4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill P. M.; Amewu R. K.; Nixon G. L.; ElGarah F. B.; Mungthin M.; Chadwick J.; Shone A. E.; Vivas L.; Lander H.; Barton V.; Muangnoicharoen S.; Bray P. G.; Davies J.; Park B. K.; Wittlin S.; Brun R.; Preschel M.; Zhang K. S.; Ward S. A. Identification of a 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane antimalarial drug-development candidate (RKA 182) with superior properties to the semisynthetic artemisinins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5693–5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. F.; Zhao Q. J.; Vargas M.; Dong Y. X.; Sriraghavan K.; Keiser J.; Vennerstrom J. L. The activity of dispiro peroxides against Fasciola hepatica. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 5320–5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorai P.; Dussault P. H. Mild and efficient Re(VII)-catalyzed synthesis of 1,1-dihydroperoxides. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4577–4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca L.; Giacomelli G.; Taddei M. An easy and convenient synthesis of Weinreb amides and hydroxamates. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 2534–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K. J.; Kim M. Direct synthesis of Weinreb amides from carboxylic acids using triphosgene. Lett. Org. Chem. 2007, 4, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Li J.; Xiao X.; Xie Y.; Shi Y. An efficient synthesis of optically active trifluoromethyl aldimines via asymmetric biomimetic transamination. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1404–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti F.; Chadwick J.; Amewu R. K.; Burrell-Saward H.; Srivastava A.; Ward S. A.; Sharma R.; Berry N.; O’Neill P. M. Second generation analogues of RKA182: synthetic tetraoxanes with outstanding in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activities. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 661–665. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks P. A.; Bray P. G.; Barton V. E.; Al-Helal M.; Jones M.; Araujo N. C.; Gibbons P.; Ward S. A.; Hughes R. H.; Biagini G. A.; Davies J.; Amewu R.; Mercer A. E.; Ellis G.; O’Neill P. M. Evidence for a common non-heme chelatable-iron-dependent activation mechanism for semisynthetic and synthetic endoperoxide antimalarial drugs. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6278–6283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill P. M.; Pugh M.; Stachulski A. V.; Ward S. A.; Davies J.; Park B. K. Optimisation of the allylsilane approach to C-10 deoxo carba analogues of dihydroartemisinin: synthesis and in vitro antimalarial activity of new, metabolically stable C-10 analogues. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 2682–2689. [Google Scholar]

- Ploemen I. H. J.; Prudencio M.; Douradinha B. G.; Ramesar J.; Fonager J.; van Gemert G. J.; Luty A. J. F.; Hermsen C. C.; Sauerwein R. W.; Baptista F. G.; Mota M. M.; Waters A. P.; Que I.; Lowik C.; Khan S. M.; Janse C. J.; Franke-Fayard B. M. D. Visualisation and quantitative analysis of the rodent malaria liver stage by real time imaging. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo M. J.; Bom J.; Capela R.; Casimiro C.; Chambel P.; Gomes P.; Iley J.; Lopes F.; Morais J.; Moreira R.; de Oliveira E.; do Rosario V.; Vale N. Imidazolidin-4-one derivatives of primaquine as novel transmission-blocking antimalarials. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale N.; Matos J.; Gut J.; Nogueira F.; do Rosario V.; Rosenthal P. J.; Moreira R.; Gomes P. Imidazolidin-4-one peptidomimetic derivatives of primaquine: Synthesis and antimalarial activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4150–4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.