Abstract

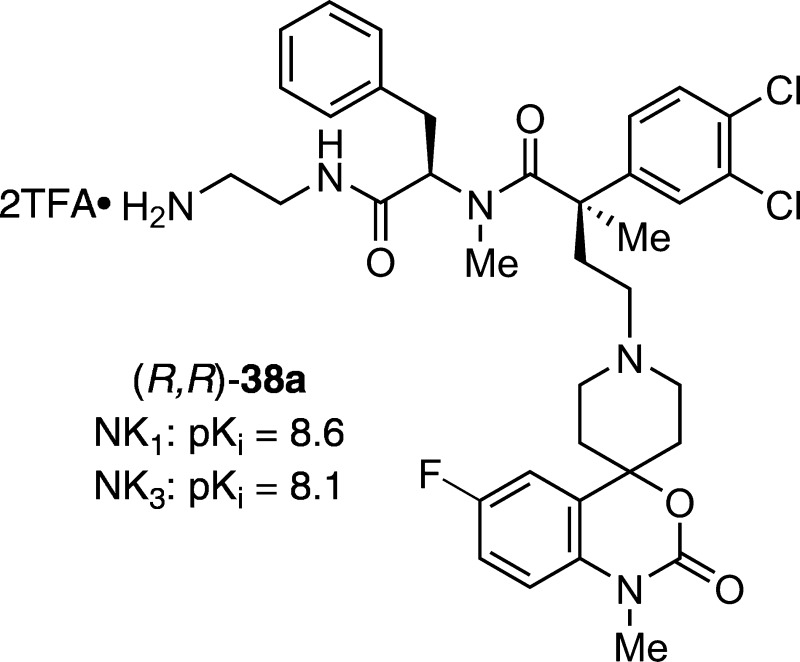

In connection with a program directed at potent and balanced dual NK1/NK3 receptor ligands, a focused exploration of an original class of peptidomimetic derivatives was performed. The rational design and molecular hybridization of a novel phenylalanine core series was achieved to maximize the in vitro affinity and antagonism at both human NK1 and NK3 receptors. This study led to the identification of a new potent dual NK1/NK3 antagonist with pKi values of 8.6 and 8.1, respectively.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, peptidomimetic, dual NK1/NK3 receptor antagonists, molecular hybridization

Both neurokinin 1 (NK1) and neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptors are localized in the corticolimbic structures of the brain.1 They modulate dopaminergic transmission, play a role in the control of mood, and are involved in the response to stress, exposure to psychostimulants, and risk factors for the induction of psychoses. Behavioral studies of neurokinin 3 antagonists in rodents suggest potential utility in the treatment of schizophrenia.2−5 In a recent report, we described a novel series of small molecules derived from a phenylglycine core and intended as dual human NK1/NK3 receptor antagonists for the potential treatment of schizophrenia.6 These compounds exhibited in vitro preferential NK1 antagonist activity for the NK1 receptor (Ki = 7.8) for the most active analogue, but insufficient NK3 receptor antagonism (pKi = 6.0 or less). In an effort to identify modifications that enhance NK3 receptor antagonism yet preserve or augment already established NK1 receptor affinity, we explored structure–activity relationships (SAR) focusing on modifications of the N- and C-terminal regions of the original motif.

In line with these objectives, we first examined the aminoethyl appendage in order to modulate the C-terminal side-chain in which the original phenylglycine central core was replaced by a d- or l-phenylalanine residue. Given the superior NK1 receptor potency observed for the conformationally restricted N-methylated ligand, we started with a first generation series containing a central N-methyl phenylalanine core.7

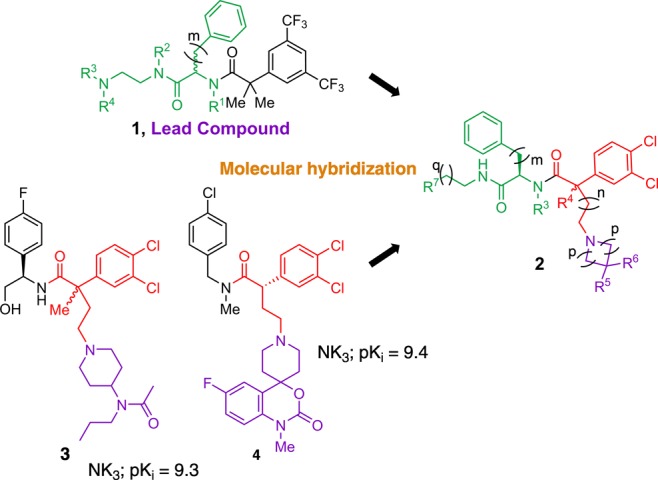

Molecular hybridization is a well-recognized strategy of rational design of new ligands based on the recognition of pharmacophoric subunits in the molecular structure of two or more known bioactive derivatives.8−10 The appropriate fusion of these subunits can lead to the design of new hybrid architectures with the prospects of combining preselected characteristics of the original template.

In this context, we turned our attention to the known α-aryl acetamide derivatives 3 and 4 as potent and selective NK1 receptor antagonists.11−16 Both series are structurally related with a common 3,4-dichlorophenyl acetic acid unit, either mono- or disubstituted at the benzylic position, linked via an alkyl spacer to a piperidinyl or spiropiperidinyl motif. We hypothesized that the combination of this moiety with our previously identified6N-(2-aminoethyl)phenylalanine pharmacophore, tethered by a 3,4-dichlorophenyl acetyl unit, could produce a new hybrid compound 2 with potentially improved and balanced affinity for the NK1 and NK3 receptors (Figure 1). Although difficult to predict, it was hoped that reduced backbone flexibility17 would lead to favorable pharmacokinetics, ultimately resulting in enhanced potency and selectivity.

Figure 1.

Rational design of dual NK1/NK3 receptor antagonists (generic structure 2) by applying the molecular hybridization approach to our hit structure 1(6) and potent NK3R antagonists 3 and 4 (Hoffmann–La Roche).11,14

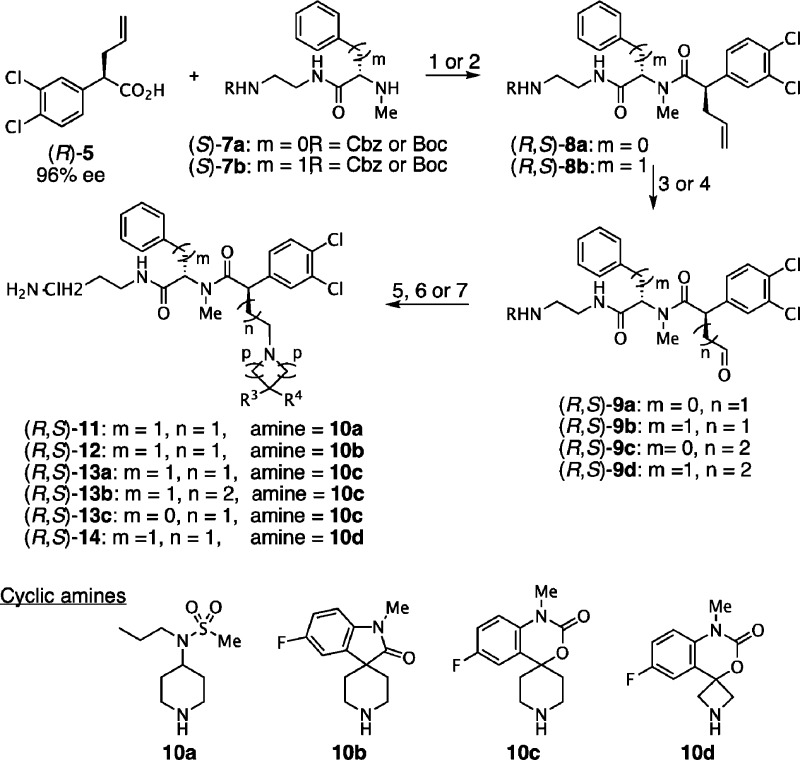

The synthetic strategy developed for the preparation of the N-methyl compounds 11–14 is outlined in Scheme 1. It started from chiral acid (R)-5, or its enantiomer (S)-6, efficiently obtained by monoallylation of commercially available 3,4-dichlorophenylacetic acid followed by resolution as diastereomeric salts with (+)- and (−)-α-methylbenzylamine, respectively,18−22 with high enantioselectivity (≥96% ee).23−28 Phenylglycine and phenylalanine building blocks (S)-7a,b were concisely obtained by acylation of monoprotected α,ω-alkanediamines7,29,30 with N-methylated aminoacids.7,31,32

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the N-Methylated Analogues 11–14.

Reagents and conditions: (1) BOP, Hünig’s base, THF, r.t., 12 h, 99% 9:1 dr; (2) DEPBT, Hünig’s base, THF, 0 °C to r.t., 8 h, 94%, 4:1 dr; (3) (i) NMO (50 wt % in H2O), OsO4 (4 wt % in H2O), H2O–THF (1:3, v/v), r.t.; (ii) NaIO4, r.t., 87%; (4) (i) catecholborane, RhCl(PPh3)3 (3 mol %), THF, 0 °C to r.t. then H2O2 (30% w/w), EtOH, phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 0 °C to r.t.; (ii) DMP, CH2Cl2, r.t., 8 h, 55 to 95% (2-steps); (5) 10a–d, DCE or CH2Cl2, 3 Å MS, r.t. then NaBH(OAc)3, r.t., 42 to 90%; (6) R = Cbz, (i) H2 (1 atm), Pd/C (10 wt %), EtOH, 4 M HCl in dioxane, r.t.; (ii) RP-HPLC-prep, 32 to 60%; (7) R = Boc, (i) HCl(g), EtOAc, 0 °C to r.t.; (ii) RP-HPLC-prep, 40 to 57%.

With the C2 stereochemistry set, conversion to amides (R,S)-8a,b was done via standard solution-phase peptide synthesis with N-Boc or N-Cbz protected N-methyl amines (S)-7 using DEPBT33 or BOP34 and Hünig’s base. We explored a variety of coupling protocols to form the N-methyl amide linkage. Not unexpectedly, partial epimerization of the allylic α-center was observed {9:1 dr for (R,S)-8a and 4:1 dr for (R,S)-8b}. However, simple separation of diastereomers by silica gel flash chromatography easily afforded enantiopure (R,S)-8a,b in good yields. The one-pot, two-step oxidation of the allyl side chain with osmium tetroxide and N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMO) followed by sodium periodate cleavage afforded aldehydes (R,S)-9a,b in good yields. Alternatively, amides (R,S)-8a,b were converted to the corresponding primary alcohols via a regioselective hydroboration with catecholborane in the presence of Wilkinson’s catalyst and subsequent oxidative workup using aqueous H2O2 under neutral conditions.35,36 Oxidation of these alcohols with Dess–Martin periodinane (DMP)37,38 in CH2Cl2 afforded aldehyde (R,S)-9c and (R,S)-9d in 95% overall yield. Reductive amination with 4-substituted piperidine 10a,13,39,40 spirocyclic oxindole 10b,41−45 spiropiperidine 10c,14,46,47 and spiroazetidine 10d(48,49)) with aldehydes 9a to 9d using sodium triacetoxyborohydride in 1,2-dichloroethane50,51 (DCE) afforded the corresponding tertiary amines in moderate to excellent yields. The synthesis was completed by deprotection of the N-Cbz- or N-Boc carbamate groups by hydrogenation or acidolysis, respectively, followed by final purification using preparative RP-HPLC to afford compounds (R,S)-11 to 14. The corresponding diastereoisomers (S,S)-11, (S,S)-12, and (S,S)-13a,b were prepared using similar strategies starting from (S)-6.7,31,32

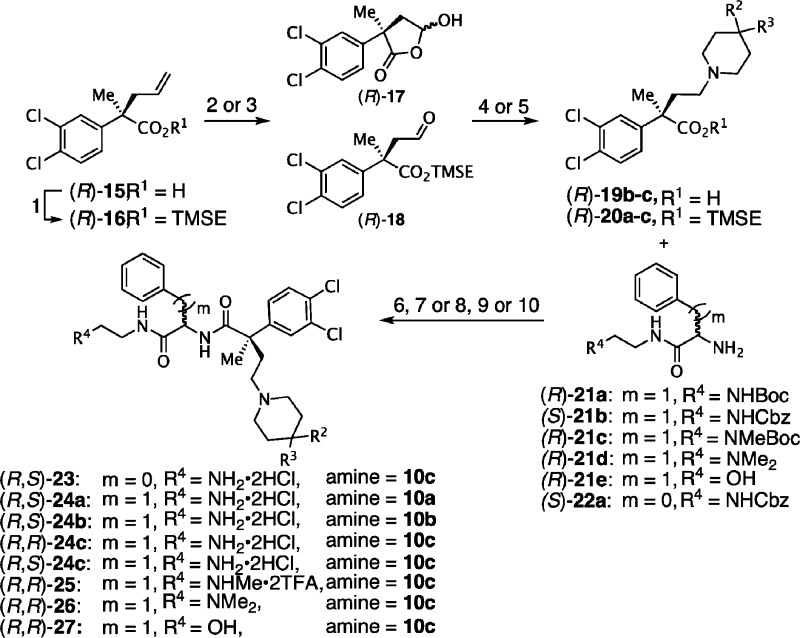

We next investigated the effect of a methyl substituent on the benzylic carbon adjacent to the 3,4-dichlorophenyl ring rather than linked to the nitrogen as exemplified by the second generation analogues (R,S)-23 to 27 as shown in Scheme 2. Optically pure acid (R)-15 with the all-carbon quaternary stereogenic center was obtained by an efficient resolution (≥96% ee) by fractional crystallization of diastereomeric salts.19,52−54 TMSE ester (R)-16 was subjected to dihydroxylation and subsequent one-pot oxidative cleavage using NaIO4 to give aldehyde (R)-18.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the C-Methylated α,α-Disubstituted Analogues 23–27.

Reagents and conditions: (1) HO(CH2)2Si(CH3)3, EDC, Pyr, THF, r.t., 12 h, 61%; (2) NaIO4, OsO4 (4 wt % in H2O/THF (1:3, v/v), r.t.; (3) (i) NMO (50 wt % in H2O), OsO4 (4 wt % in H2O), H2O–THF (1:3, v/v), r.t.; (ii) NaIO4, r.t.; (4) 10a–c, DCE or CH2Cl2, 3 Å MS, r.t. then NaBH(OAc)3, r.t., 43 to 73% (2-steps); (5) TBAF, THF, r.t., 1 h; (6) HBTU, Hünig’s base, THF, r.t., 12 h, 65 to 85% (2-steps); (7) PyBOP, DMAP, Hünig’s base, THF, CH2Cl2, r.t.; (8) R4 = NHBoc, (i) HCl(g), EtOAc, 0 °C to r.t.; (ii) RP-HPLC-prep, 40–63%; (9) R4 = NHCbz, (i) H2 (1 atm), Pd/C (10 wt %), EtOH, 4 M HCl in dioxane, r.t.; (ii) RP-HPLC-prep, 35 to 59%; (10) R4 = NMeBoc, (i) TFA, CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h 76%; (ii) lyophilization.

Alternatively, direct OsO4-catalyzed oxidative cleavage of acid (R)-15 afforded hemiacetal (R)-17 as a diastereomeric mixture. Piperidine 10a or spiropiperidine 10b,c motifs were efficiently introduced by reductive amination using sodium triacetoxyborohydride in DCE50,51 or sodium cyanoborohydride in methanol,55 respectively. Acids (R)-19b to (R)-19c or TMSE esters (R)-20a–c, pretreated with TBAF in THF, were coupled with primary amines7,56 (S)-21b, (R)-21a,c–e, and (S)-22 using standard peptide coupling conditions (HBTU57 or PyBOP58). Finally, the amino protecting groups were removed by acidolysis or hydrogenolysis to yield the desired products (R,S)-23 and (R,S)-24a–c that were further purified by RP-HPLC affording the corresponding dihydrochloride salts after lyophilization. Compounds (S,S)-23, (S,S)-24a–c, and (S,R)-24b were prepared from enantioenriched acid (S)-22 using a similar route.7

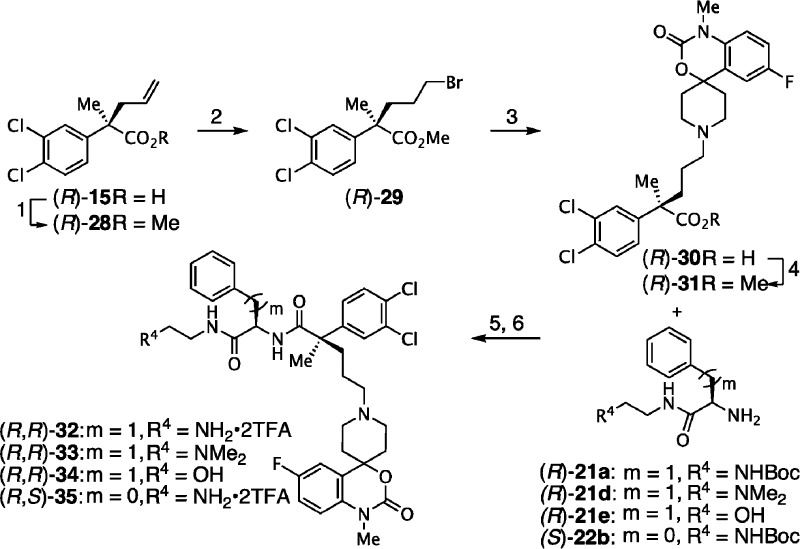

In order to explore the effect of linker length between the 3,4-dichlorophenyl acetamide core and the piperidine pharmacophore, compounds 32–35 bearing a C-methyl substituent on the benzylic carbon and a three-carbon spacer were prepared as described in Scheme 3. Since the synthetic routes previously described could not be applied to access these compounds, we decided to introduce the spiropiperidine moiety prior to the peptide coupling. Accordingly, methyl ester (R)-28 was treated with hydrogen bromide in toluene under free-radical conditions to provide bromide (R)-29 in 80% yield. Nucleophilic displacement with spiropiperidine 10c, followed by saponification of the methyl ester gave the key spiropiperidine acid (R)-31 in 62% yield over two steps.7 HBTU-Mediated amide formation with the appropriate aromatic residue followed by acidolysis, if applicable, completed the synthesis of these second-generation analogues.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the C-Methylated α,α-Disubstituted Analogues 32–35 with a 3-Carbon Spacer.

Reagents and conditions: (1) SOCl2, MeOH, 0 °C to r.t., 12 h, 99%; (2) HBr(g), cat. mCPBA, PhMe, 0 °C, 2 h; (3) 10c, Cs2CO3, DMF, r.t., 4 h; (4) aq. LiOH, THF, reflux, 12 h, 52% (3-steps); (5) HBTU, Hünig’s base, THF, r.t., 65 to 85%; (6) TFA, CH2Cl2 (1:1, v/v), 0 °C to r.t., 65 to 75%.

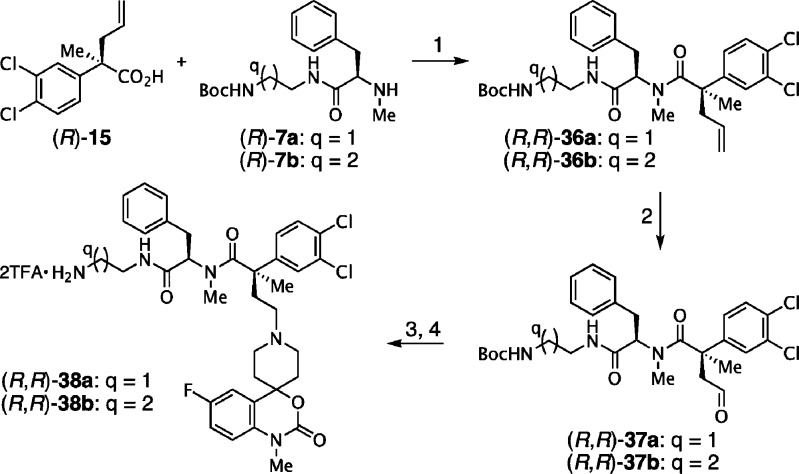

Finally, we focused on the synthesis of third-generation N,C-bismethylated α,α-disubstituted backbone peptidomimetic analogues.59−61 The challenging synthesis of these sterically congested derivatives could not be achieved using the peptide coupling conditions we previously developed. However, acylation with amines (R)-7b,c with enantioenriched acid chloride of (R)-15 in the presence of pyridine, afforded the desired amides (R,R)-36a,b (Scheme 4). Subjection of the allyl side-chain to Lemieux–Johnson conditions provided aldehydes (R,R)-37a,b, which were then reacted with spiropiperidine 10b using sodium cyanoborohydride in methanol.55 Finally, upon exposure to TFA in dichloromethane, N-Boc deprotection yielded the desired peptidomimetics (R,R)-38a,b as their TFA salts in good overall yield.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of the N,C-Bismethylated α,α-Disubstituted Analogues 38a–b.

Reagents and conditions (1) (i) SOCl2, PhH, reflux, 12 h; (ii) Pyr, THF, r.t., 35–70% (2-steps); (2) (i) NMO (50 wt % in H2O), OsO4 (4 wt % in H2O), H2O–THF (1:3, v/v), r.t.; (ii) NaIO4, r.t.; (3) 10b, NaBH3CN, MeOH, r.t., 50–65% (2-steps); (4) TFA, CH2Cl2 (1:1, v/v), 75%.

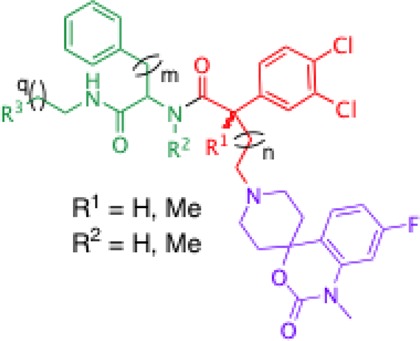

The binding affinity of these hybrid compounds for human NK1 and NK3 receptors was determined using radioligand binding assays on membranes prepared from U-373MG cells endogenously expressing NK1 receptors and recombinant CHO cells stably expressing NK3 receptors.7 The results for selected compounds are presented in Table 1. Well balanced antagonism was observed especially with compounds bearing a benzylic quaternary C-methyl group (Table 1, entries 6, 9, 13, 14, 16). Whereas the N-methylated analogues (entries 1–5) showed good NK1 receptor activity, only moderate NK3 receptor antagonism was exhibited. Furthermore, the (R,R) configuration seems to be optimal for activity against NK1/NK3 receptor ligands. Extension of the methylene spacer arm (connecting the 3,4-dichlorophenyl acetamide and the spiropiperidine pharmacophore) had only a moderate effect on NK1R affinity but induced a 20–50-fold reduction in NK3 receptor antagonism (Table 1, entries 3, 4, 12). Interestingly, the replacement of the (R)-phenylalanine central core by a (R)-phenylglycine residue (entries 1 vs 5, 6 vs 11, and 10 vs 12) did not significantly affect the dual antagonism, although the values remained modest. Concerning the influence of the C-terminal polar arm, the successive methylation of the primary amine group had a minor effect, but its replacement by an alcohol led to 12–20-fold improvement of the NK3 receptor affinity (Table 1, entry 16).

Table 1. pKi Values of Hybrid Peptidomimetics 13, 23–27, 32–35, and 38 at Both Human NK1 and NK3 Receptors Determined by Competitive Binding Assaysa.

| pKi |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | compd | R3 | n | m | q | hNK1 | hNK3 |

| 1 | (R,S)-13ad | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.9 | 5.8 |

| 2 | (S,S)-13ad | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.7 | 5.9 |

| 3 | (R,S)-13bc | NH2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7.3 | 5.4 |

| 4 | (S,S)-13bc | NH2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6.4 | 5.2 |

| 5 | (R,S)-13cc | NH2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6.2 | 5.6 |

| 6 | (R,S)-24ce | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.9 | 7.2 |

| 7 | (S,S)-24cc | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.4 | 5.0 |

| 8 | (S,R)-24cd | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.2 | 5.7 |

| 9 | (R,R)-24ce | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.7 | 7.3 |

| 10 | (R,R)-32 | NH2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7.2 | 5.8 |

| 11 | (R,S)-23c | NH2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 | 7.4 |

| 12 | (R,S)-35 | NH2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6.5 | 6.1 |

| 13 | (R,R)-25 | NHMe | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.8 | 7.7 |

| 14 | (R,R)-26 | NMe2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| 15 | (R,R)-33 | NMe2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7.7 | 6.0 |

| 16 | (R,R)-27 | OH | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 | 8.6 |

| 17 | (R,R)-34 | OH | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7.8 | 6.9 |

| 18 | (R,R)-38a | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.6 | 8.1 |

| 19 | (R,R)-38b | NH2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8.4 | 7.6 |

Evaluation of the binding affinity (pKi) of compounds at both (a) human NK1 receptor and (b) human NK3 receptor was done using [125I]-Bolton Hunter-Substance P and [3H]-SR142801 as radioligands, respectively. Data represent n = 2 independent determinations performed in duplicate; SD < 0.2 pKi.6 The selective NK1 antagonist, vestipitant, displayed high affinity at NK1 receptors (pKi = 9.5), yet negligible affinity for NK3 receptors (pKi = 5.5 or less), while the selective NK3 antagonist, talnetant, displayed high affinity for NK3 receptors (pKi = 8.5) and negligible affinity for NK1 receptors.11,14

Although promising NK1R and NK3R antagonist activity was seen with some third generation analogues, we were curious to see the effect of modifying the backbone conformation in N,C-bismethylated analogues. To our delight, the (R,R)-N,C-bismethylated analogue, 38a emerged as the most potent and well balanced dual antagonist (Table 1, entry18).

In conclusion, we have prepared a series of hybrid analogues inspired from our previously reported lead compounds (generic structure 1) and the Hoffmann–La Roche NK3 receptor antagonists 3 and 4 using phenylalanine as a central motif. In the course of this study, three generations of peptidomimetic hybrids were concisely synthesized from three sets of versatile building blocks. As a result of our lead optimization, we have found compounds with very promising in vitro antagonist activity against hNK1 and hNK3 receptors. Among these, analogue (R,R)-38a has particularly high and balanced affinities displaying pKi values that compare favorably to the known compounds 3 and 4 (Figure 1). Further optimizations in this series are in progress and will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

The Université de Montréal group thanks the excellent technical assistance of Marie-Christine Tang, Karine Venne, and Alexandra Furtos from the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory of Université de Montréal.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- NK1

neurokinin 1

- NK3

neurokinin 3

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedures, analytical data, and assay descriptions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

∥ (N.B.) Ra Pharmaceuticals, Inc., One Kendall Square, Suite B14301, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

This work was supported by the Institut de Recherches Servier, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and the Fonds quebecois de la recherché sur la nature et les technologies (FQRNT).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Almeida T. A.; Rojo J.; Nieto P. M.; Pinto F. M.; Hernandez M.; Martín J. D.; Candenas M. L. Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: structure and activity relationships. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson C.; Lee T. H.; Ellinwood E. H. The NK(1) receptor antagonist WIN51708 reduces sensitization after chronic cocaine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 499, 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren W.; Riemer C.; Meltzer H. Opinion: NK3 receptor antagonists: the next generation of antipsychotics?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson L. A.; Smith P. W. Therapeutic utility of NK3 receptor antagonists for the treatment of schizophrenia. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example of dual NK1/NK3 antagonists for the treatment of Schizophrenia, see also:Alvaro G.; Andreotti A.; Belvedere S.; Di Fabio R.; Falchi A.; Giovannini R.. Pyridine derivatives and their use in the treatment of psychotic disorders. WO2007028654, 2007.

- Hanessian S.; Babonneau V.; Boyer N.; Mannoury LaCour C.; Millan M. J.; De Nanteuil G. Design and synthesis of potential dual NK1/NK3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See Supporting Information for experimental details

- Lu J.-J.; Pan W.; Hu Y.-J.; Wang Y.-T. Multi-target drugs: the trend of drug research and development. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J. Dual- and triple-acting agents for treating core and co-morbid symptoms of major depression: novel concepts, new drugs. Neurotherapeutics 2009, 6, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D.; Jiang X.; Zhou L.; Chen J.; Chen Z.; He C.; Yang K.; Liu Y.; Pei J.; Lai L. Discovery of multitarget inhibitors by combining molecular docking with common pharmacophore matching. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.-U.; Hoffmann T.; Schnider P.; Stadler H.; Koblet A.; Alker A.; Poli S. M.; Ballard T. M.; Spooren W.; Steward L.; Sleight A. Discovery of potent, balanced and orally active dual NK1/NK3 receptor ligands. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knust H.; Nettekoven M.; Ratni H.; Vifian W.; Wu X.. Piperidine derivatives as NK3 receptor antagonists. PCT Int. Appl., WO2009033995, 2009.

- Caroon J. M.; Dillon M. P.; Han B.; Nettekoven M.; Ratni H.; Vifian W.. Spiropiperidine Derivatives as NK3 antagonists. PCT Int. Appl., WO2008081012, 2008.

- Bissantz C.; Hoffmann T.; Jablonski P.; Knust H.; Nettekoven M.; Ratni H.; Wu X. Pyrrolidine derivatives as dual NK1/NK3 receptor antagonists. PCT Int. Appl., WO2008128891, 2008.

- Schnider P.Dual NK1/NK3 antagonists against Schizophremia. PCT Int. Appl., WO2006013050, 2006.

- Hoffmann T.; Koblet A.; Peters J. U.; Schnider P.; Sleight A.; Stadler H.. Dual NK1/NK3 antagonists for treating schizophremia. PCT Int. Appl.,WO2005002577, 2005.

- See alsoCatalani M. P.; Alvaro G.; Bernasconi G.; Bettini E.; Bromidge S. M.; Heer J.; Tedesco G.; Tommasi S. Identification of novel NK1/NK3 dual antagonists for the potential treatment of schizophrenia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurelio L.; Brownlee R. T. C.; Hughes A. B. Synthetic preparation of N-methyl-α-amino acids. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 5823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak A.; Marino D.; Vicario P. P.; Ayala J. M.; Cascierri M. A.; Parsons W.; Mills S. G.; MacCoss M.; Yang L. Novel, orally bioavailable γ-aminoamide CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. K.; Chen N.; Guthikonda R. N.; Mills S. G.; Malkowitz L.; Springer M. S.; Gould S. L.; DeMartino J. A.; Carella A.; Carver G.; Holmes K.; Schleif W. A.; Danzeisen R.; Hazuda D.; Kessler J.; Lineberger J.; Miller M.; Emini E. A.; MacCoss M. Synthesis and evaluation of CCR5 antagonists containing modified 4-piperidinyl-2-phenyl-1-(phenylsulfonylamino)-butane. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn C. P.; Finke P. E.; Oates B.; Budhu R. J.; Mills S. G.; MacCoss M.; Malkowitz L.; Springer M. S.; Daugherty B. L.; Gould S. L.; DeMartino J. A.; Siciliano S. J.; Carella A.; Carver G.; Holmes K.; Danzeisen R.; Hazuda D.; Kessler J.; Lineberger J.; Miller M.; Schleif W. A.; Emini E. A. Antagonists of the human CCR5 receptor as anti-HIV-1 agents. Part 1: Discovery and initial structure–activity relationships for 1-amino-2-phenyl-4-(piperidin-1-yl)butanes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke P. E.; Meurer L. C.; Oates B.; Mills S. G.; MacCoss M.; Malkowitz L.; Springer M. S.; Daugherty B. L.; Gould S. L.; DeMartino J. A.; Siciliano S. J.; Carella A.; Carver G.; Holmes K.; Danzeisen R.; Hazuda D.; Kessler J.; Lineberger J.; Miller M.; Schleif W. A.; Emini E. A. Antagonists of the human CCR5 receptor as anti-HIV-1 agents. Part 2: Structure–activity relationships for substituted 2-aryl-1-[N-(methyl)-N-(phenylsulfonyl)amino]-4-(piperidin-1-yl)butanes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale J. J.; Finke P. E.; MacCoss M. A facile synthesis of the novel Neurokinin A antagonist SR 48968. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1993, 3, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J. S.; Simonovich S. P.; Jamison C. R.; MacMillan D. W. C. Enantioselective α-arylation of carbonyls via Cu(I)-bisoxazoline catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigot A.; Williamson A. E.; Gaunt M. J. Enantioselective α-arylation of N-acyloxazolidinones with copper(II)-bisoxazoline catalysts and diaryliodonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owston N. A.; Fu G. C. Asymmetric alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings of unactivated secondary alkyl electrophiles: stereoconvergent suzuki reactions of racemic acylated halohydrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin P. M.; Fu G. C. Asymmetric Suzuki cross-couplings of activated secondary alkyl electrophiles: arylations of racemic α-chloroamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrus M. B.; Harper K. C.; Christiansen M. A.; Binkley M. A. Phase-transfer catalyzed asymmetric arylacetate alkylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 4541. [Google Scholar]

- Dai X.; Strotman N. A.; Fu G. C. Catalytic asymmetric Hiyama cross-couplings of racemic α-bromo esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapcho A. P.; Kuell C. S. Mono-protected diamines. N-tert-Butoxycarbonyl-α,ω-alkanediamines from α,ω-alkanediamines. Synth. Commun. 1990, 20, 2559. [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas S. J.; Tamanini E.; Todd M. H.; Watkinson M. Effective methods for the biotinylation of azamacrocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A. B.; Sleebs B. E. Effective methods for the synthesis of N-methyl β-amino acids from all twenty common α-amino acids using 1,3-oxazolidin-5-ones and 1,3-oxazinan-6-ones. Helv. Chim. Acta 2006, 89, 2611. [Google Scholar]

- Freidinger R. M.; Hinkle J. S.; Perlow D. S.; Arison B. H. Synthesis of 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl-protected N-alkyl amino acids by reduction of oxazolidinones. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. E.; Coyne A. G.; Hudson S. A.; Abell C. Fragment-based approaches in drug discovery and chemical biology. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro B.; Dormoy J. R.; Evin G.; Selve C. Reactifs de couplage peptidique I (1)-l′hexafluorophosphate de benzotriazolyl N-oxytrisdimethylamino phosphonium (B.O.P.). Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 16, 1219. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Fu G. C.; Hoveyda A. H. Rhodium(I)- and iridium(I)-catalyzed hydroboration reactions: scope and synthetic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 6671. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Fu G. C.; Anderson B. A. Mechanistic study of the rhodium(I)-catalyzed hydroboration reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 6679. [Google Scholar]

- Dess D. B.; Martin J. C. A useful 12-I-5 triacetoxyperiodinane (the Dess–Martin periodinane) for the selective oxidation of primary or secondary alcohols and a variety of related 12-I-5 species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 7277. [Google Scholar]

- Dess D. B.; Martin J. C. Readily accessible 12-I-5 oxidant for the conversion of primary and secondary alcohols to aldehydes and ketones. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 4155. [Google Scholar]

- Massé J.; Langlois N. Synthesis of 5-amino and 4-hydroxy-2-phenylsulfonylmethylpiperidines. Heterocycles 2009, 77, 417. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori K.; Sajiki H.; Hirota K. Pd/C(en)-Catalyzed chemoselective hydrogenation with retention of the N-Cbz protective group and its scope and limitations. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 8433. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer N.; Gloanec P.; De Nanteuil G.; Jubault P.; Quirion J.-C. Synthesis of α,α-difluoro-β-amino esters or gem-difluoro-β-lactams as potential metallocarboxypeptidase inhibitors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 4277. [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. G.; Robichaud A. J. Synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted oxindoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 461. [Google Scholar]

- Teng D.; Zhang H.; Mendonca A. An efficient synthesis of a spirocyclic oxindole analogue. Molecules 2006, 11, 700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignan G. C.; Battista K.; Connolly P. J.; Orsini M. J.; Liu J.; Middleton S. A.; Reitz A. B. Preparation of 3-spirocyclic indolin-2-ones as ligands for the ORL-1 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 5022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund R. A convenient synthetic route to spiro[indole-3,4′-piperidin]-2-ones. Helv. Chim. Acta 2000, 83, 1247. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. D.; Caroon J. M.; Kluge A. F.; Repke D. B.; Roszkowski A. P.; Strosberg A. M.; Baker S.; Bitter S. M.; Okada M. D. Synthesis and antihypertensive activity of 4′-substituted spiro[4H-3,1-benzoxazine-4,4′-piperidin]-2(1H)-ones. J. Med. Chem. 1983, 26, 657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Krasovskiy A.; Trépanier V. E.; Chen D. Y.-K. An expedient strategy for the synthesis of tryptamines and other heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4217–4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde D. C.; Corless M.; Fenwick D. R.; Mason H. J.; Stammen B. C.; Stephenson P. T.; Ellis D.; Bachelor D.; Gordon D.; Barber C. G.; Wood A.; Middleton D. S.; Blakemore D. C.; Parsons G. C.; Eastwood R.; Platts M. Y.; Statham K.; Paradowski K. A.; Burt C.; Klute W. The design and discovery of novel amide CCR5 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Hong S.-P.; Chen B.; Eldemenky E.; Husain A.; Wu L.; Lu K.; Ma G.; Labelle M.; Marzabadi M.; Sabio M.; White A.; Mazza C.; Packiarajan M.. Indole Derivatives. WO/2009/120655, 2009.

- Abdel-Magid A. F.; Mehrman S. J. A review on the use of sodium triacetoxyborohydride in the reductive amination of ketones and aldehydes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006, 10, 971. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Magid A. F.; Carson K. G.; Harris B. D.; Maryanoff C. A.; Shah R. D. Reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones with sodium triacetoxyborohydride. studies on direct and indirect reductive amination procedures. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S.; List B. Chiral counteranions in asymmetric transition-metal catalysis: highly enantioselective Pd/Brønsted acid-catalyzed direct α-allylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielvogel D. J.; Buchwald S. L. Nickel-BINAP catalyzed enantioselective α-arylation of α-substituted γ-butyrolactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canet J.-L.; Fadel A.; Salaün J. Asymmetric construction of quaternary carbons from chiral malonates: selective and versatile total syntheses of the enantiomers of α- and β-cuparenones from a common optically active precursor. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3463. [Google Scholar]

- Borch R. F.; Bernstein M. D.; Dupont Durst H. Cyanohydridoborate anion as a selective reducing agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2897. [Google Scholar]

- Amines 28a–e and 29a–b were prepared by solution-phase peptide coupling between the corresponding N-protected phenylglycine or phenylalanine amino acid and 2-substituted ethylamines, followed by appropriate deprotection at the N-terminus.

- Dourtoglou V.; Gross B.; Lambropoulou V.; Zioudrou C. O-Benzotriazolyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate as coupling reagent for the synthesis of peptides of biological interest. Synthesis 1984, 572. [Google Scholar]

- Coste J.; Le-Nguyen D.; Castro B. PyBOP: a new peptide coupling reagent devoid of toxic by-product. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Maes V.; Tourwé D. In Peptide and Protein Design for Biopharmaceutical Applications; Jensen K. J., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 2009; pp 49–131 [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci L.; De Marco R.; Cerisoli L. Chemical modifications designed to improve peptide stability: incorporation of non-natural amino acids, pseudo-peptide bonds, and cyclization. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauer A.; König B. Peptidomimetics: a versatile route to biologically active compounds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5099. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.