Abstract

Objective To determine if earlier administration of epinephrine (adrenaline) in patients with non-shockable cardiac arrest rhythms is associated with increased return of spontaneous circulation, survival, and neurologically intact survival.

Design Post hoc analysis of prospectively collected data in a large multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests (Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation).

Setting We utilized the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation database (formerly National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, NRCPR). The database is sponsored by the American Heart Association (AHA) and contains prospective data from 570 American hospitals collected from 1 January 2000 to 19 November 2009.

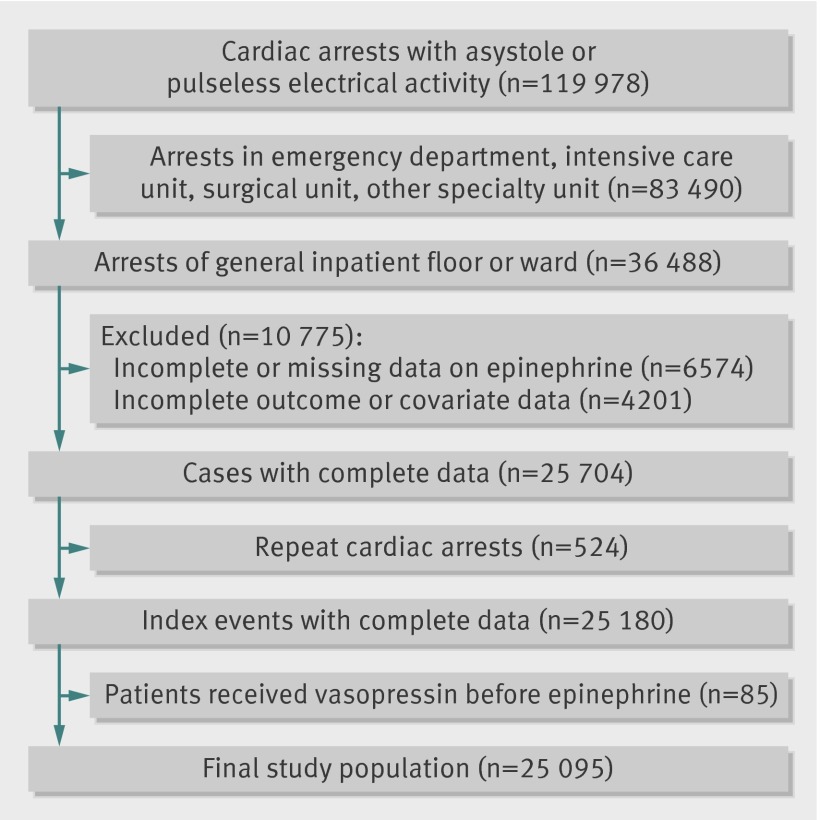

Participants 119 978 adults from 570 hospitals who had a cardiac arrest in hospital with asystole (55%) or pulseless electrical activity (45%) as the initial rhythm. Of these, 83 490 arrests were excluded because they took place in the emergency department, intensive care unit, or surgical or other specialty unit, 10 775 patients were excluded because of missing or incomplete data, 524 patients were excluded because they had a repeat cardiac arrest, and 85 patients were excluded as they received vasopressin before the first dose of epinephrine. The main study population therefore comprised 25 095 patients. The mean age was 72, and 57% were men.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included sustained return of spontaneous circulation, 24 hour survival, and survival with favorable neurologic status at hospital discharge.

Results 25 095 adults had in-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms. Median time to administration of the first dose of epinephrine was 3 minutes (interquartile range 1-5 minutes). There was a stepwise decrease in survival with increasing interval of time to epinephrine (analyzed by three minute intervals): adjusted odds ratio 1.0 for 1-3 minutes (reference group); 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.00; P=0.055) for 4-6 minutes; 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88; P<0.001) for 7-9 minutes; and 0.63 (0.52 to 0.76; P<0.001) for >9 minutes. A similar stepwise effect was observed across all outcome variables.

Conclusions In patients with non-shockable cardiac arrest in hospital, earlier administration of epinephrine is associated with a higher probability of return of spontaneous circulation, survival in hospital, and neurologically intact survival.

Introduction

Each year, about 200 000 patients in hospital in the United States have a cardiac arrest,1 with survival at 7-26%.2 3 4 5 6 Initial cardiac rhythms not amenable to defibrillation (pulseless electrical activity and asystole) are more common than shockable rhythms (ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia) in the inpatient7 and outpatient settings,8 and the past decade has seen a trend toward an increased incidence of non-shockable arrests.9 Despite the predominance of non-shockable cardiac rhythms, most previous studies have focused on patients with shockable cardiac arrest.10 11 12 Apart from cardiopulmonary resuscitation, no intervention has been shown to be efficacious in patients with non-shockable cardiac arrest.

Epinephrine (adrenaline) is a potent peripheral vasoconstrictor as well as a coronary artery vasodilator and is recommended by the American Heart Association as the preferred medical intervention in cardiac arrest.13 14 Despite a strong physiologic rationale and anecdotal reports of efficacy, there are no well controlled trials of epinephrine to assess endpoints such as improved survival and neurologically intact survival. A randomized trial failed to show efficacy for advanced cardiac life support drugs, and extrapolation to the potential lack of efficacy of epinephrine has been suggested; the dose, timing, and even use of epinephrine remains controversial.15 16

We investigate the effects of timing of administration of epinephrine on survival after cardiac arrest in hospital. To avoid confounding by the timing of defibrillation, we excluded patients with shockable rhythms. We hypothesized that in patients with cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythm, in-hospital survival and neurologic outcome would be improved with earlier administration of epinephrine. To test this hypothesis, we used a large observational database to evaluate the relation between time of first administration of epinephrine and in-hospital survival in patients in hospital with pulseless electrical activity or asystolic cardiac arrest.

Methods

Study design

We used the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation database (formerly National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, NRCPR). The database is sponsored by the American Heart Association (AHA), and the methods associated with the database have been described previously.4 5 Briefly, the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation database is a prospective voluntary multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests. All participating institutions were required to comply with local regulatory and privacy guidelines and, if required, to secure institutional review board approval. Because data were used primarily as the local site for quality improvement, sites were granted a waiver of informed consent under the common rule. The University of Pennsylvania served as the data analytic center and granted the opportunity to prepare the data for research purposes. All patients with cardiac arrest and without do-not-resuscitate orders are screened for eligibility. Trained staff at participating institutions are responsible for screening potential cases through review of hospital paging logs, routine checks of the emergency response code carts, and cardiac arrest event documentation flow sheets. Research or quality assurance staff collect information on the cardiac arrest event from the hospital medical records and cardiac arrest documentation forms. Data are entered onto a secure electronic database that uses precisely defined variables from the Utstein guidelines for in-hospital cardiac arrest. All cases are assigned a unique identification code.

Patient population

Data from 570 hospitals were collected from 1 January 2000 to 19 November 2009. We included in the analysis only index pulseless events for which the initial cardiac rhythm was asystole or pulseless electrical activity. We excluded patients with cardiac arrest in the emergency department, intensive care unit, or surgical or other specialty care or procedure areas, patients who had incomplete, missing, or inconsistent (negative) data on time to epinephrine administration or incomplete or missing covariate data, and patients who received vasopressin before epinephrine.

Time to epinephrine

Our primary exposure of interest was the time to epinephrine administration. Time to epinephrine was recorded as the interval, in minutes, between the recognition of the cardiac arrest and the first administered dose of epinephrine. Data concerning the recognition of the arrest as well as the first administration of epinephrine were recorded initially at the time of the cardiac arrest event by the clinical team responding and subsequently entered onto the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation database, which provides training, a data dictionary, and instructions to data abstractors to increase accuracy.4 5 We constructed intervals of time to administration of epinephrine on the basis of previous recommendations.14 Intervals were categorized as administration in 1-3 minutes, 4-6 minutes, 7-9 minutes, and >9 minutes.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included sustained return of spontaneous circulation defined as the presence of palpable pulses for 20 minutes, survival to 24 hours, and survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic status.17 Neurologic status was assessed with the 5 point cerebral performance category scale (1=no major disability, 2=moderate disability, 3=severe disability, 4=coma or vegetative state, and 5=death).17 18 We dichotomized the 5 point scale into favorable (cerebral performance category 1 or 2) and poor (cerebral performance category 3, 4, or 5) neurologic status, which is commonly done in cardiac arrest investigations.11 12

Statistical analysis

To assess the independent relation between time to epinephrine administration and survival to hospital discharge, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models. With a large multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrest such as Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation, it is likely that many variables will have significant, albeit not clinically relevant, associations with the outcome of interest. Therefore, we initially screened all variables in the dataset to be used as candidate predictor variables in the multivariable models. Variables selected as candidates for entry into the multivariable models included race/ethnicity, initial cardiac rhythm (asystole or pulseless electrical activity), admission diagnosis (medical (cardiac), medical (non-cardiac), surgical (cardiac), surgical (non-cardiac)), co-existing medical conditions (congestive heart failure, new myocardial infarction at this admission, myocardial infarction before this admission, known arrhythmia, hypotension or hypoperfusion, respiratory insufficiency, renal insufficiency, hepatic insufficiency, metabolic or electrolyte abnormalities, diabetes, baseline central nervous system depression, stroke, pneumonia, septicemia, major trauma, metastatic or hematologic malignancy, HIV or AIDS), whether the arrest was witnessed, the use of apnea monitoring or use of telemetry monitoring at the time of arrest, activation of hospital-wide emergency response team, location of arrest (general inpatient floor or ward with telemetry monitoring, general inpatient floor or ward without telemetry monitoring, telemetry monitored step-down floor or ward), hospital characteristics including the hospital teaching status (major teaching center, minor teaching center, or non-teaching center), hospital size as measured by total number of hospital beds (<250, 250-499, >499), day of the week (weekday or weekend), and time of arrest (day or night). To account for changes in cardiopulmonary resuscitation guidelines we categorized patients by year of arrest, either before or after guideline changes in 2005.

We used univariate logistic regression models to determine potential associations between confounding variables and outcomes. Variables that were determined to be independently associated (P<0.05) with outcomes were then added to the multivariable models. To achieve model parsimony, variables that failed to contribute significantly to the model were removed manually to fit the final multivariable model. Regardless of significance, we planned a priori to include patients’ characteristics including age and sex, as well as recorded time to epinephrine administration and time to initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation as covariates, and these were therefore forced into the final model. The final list of predictor variables for multivariable analysis is shown in table A in appendix 1. For the final models, we used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering effects of hospitals. All analyses were carried out on complete cases, including primary predictor variable and covariate data.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed three types of sensitivity analysis. First, because delays in initiation of resuscitation will affect in-hospital survival, we performed two additional confirmatory analyses of the relation between time of epinephrine administration and outcomes. This was planned a priori to ensure that the results of our primary analysis were not simply artifacts of delays in initiation of resuscitation. In the first sensitivity analysis, we assessed the primary exposure of delay in administering epinephrine after chest compressions had begun. This analysis therefore accounted for the incremental contribution to outcomes from delays in administration rather than overall delays in resuscitation. We computed this exposure as the difference, in minutes, between initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and administration of epinephrine. We then restricted the population of interest to those patients for whom cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated within the first minute of recognition of cardiac arrest, thus eliminating variability relating to the time to initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Second, we performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis categorizing patients into quarters of the time distribution of delivery of the first epinephrine. This additional test was performed to assess residual treatment bias in timing of delivery of epinephrine as the 3 minute categorization scheme was derived a priori on the basis of expert opinion and current ACLS guidelines. We treated quarters of epinephrine delivery as the predictor of interest and used multivariable logistic regression models for the sensitivity analyses. We report adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Third, some patients were not included in the analysis because of missing covariate data (fig 1; table B in appendix 1). Using χ2, we assessed the crude survival rates in patients who were excluded from the primary analysis because of missing covariate data and compared these rates with those patients included in the primary analysis. Further, we assumed covariate data were missing at random and performed multiple imputations five times for covariate data and assessed the effect on primary outcome with multivariable logistic regression models.

Fig 1 Selection of cardiac arrest patients with pulseless electrical activity or asystole from Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry

All statistical tests of the data were two tailed at a significance level of 0.05. We report unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for statistical testing. All analyses were performed with SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

We identified 25 095 adult patients (fig 1) from 570 hospitals who had an in-hospital cardiac arrest with asystole (55%) or pulseless electrical activity (45%). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. The median time to epinephrine administration was three minutes (interquartile range 1-5 minutes), and the median number of doses administered was three (interquartile range 2-4). Sustained return of spontaneous circulation occurred in 12 215 patients (49%); 6820 (27%) survived to 24 hours and 2603 (10%) survived to hospital discharge. Of patients with complete neurologic assessment, 1601 (7%) survived with favorable neurologic outcome. Neurologic outcome data were unavailable for 359 patients (1%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with cardiac arrest in hospital. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | All patients (n=25 095) |

|---|---|

| Means (SD) age (years) | 72 (15) |

| Men | 14 364 (57) |

| White | 17 433 (70) |

| Activation of hospital-wide resuscitation response | 24 408 (97) |

| Witnessed event | 13 976 (56) |

| Asystole | 13 792 (55) |

| ECG monitor at time of arrest | 12 765 (51) |

| Weekend arrest | 8292 (33) |

| Evening or after hours arrest | 10 040 (40) |

| Location of arrest: | |

| General floor or ward with telemetry | 2433 (10) |

| General floor or ward without telemetry | 13 081 (52) |

| Telemetry monitored step-down unit | 9581 (38) |

| Hospital size (No of beds): | |

| <250 | 5364 (21) |

| 250-499 | 10 944 (44) |

| >499 | 8787 (35) |

| Admitting diagnosis: | |

| Non-cardiac | 14 088 (56) |

| Cardiac | 6549 (26) |

| Surgical non-cardiac | 3310 (13) |

| Surgical cardiac | 902 (4) |

| Other | 246 (1) |

| Co-morbid cardiac conditions: | |

| Arrhythmia | 6954 (28) |

| Previous congestive heart failure | 5899 (24) |

| New diagnosis of congestive heart failure | 4601 (18) |

| Myocardial infarction | 4030 (16) |

| Co-existing conditions: | |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 8625 (34) |

| Diabetes | 8411 (34) |

| Cancer | 4122 (16) |

| Pneumonia | 3902 (16) |

| Baseline CNS depression | 3495 (14) |

| Sepsis | 3367 (13) |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 1686 (7) |

| Trauma | 462 (2) |

ECG=electrocardiograph; CNS=central nervous system.

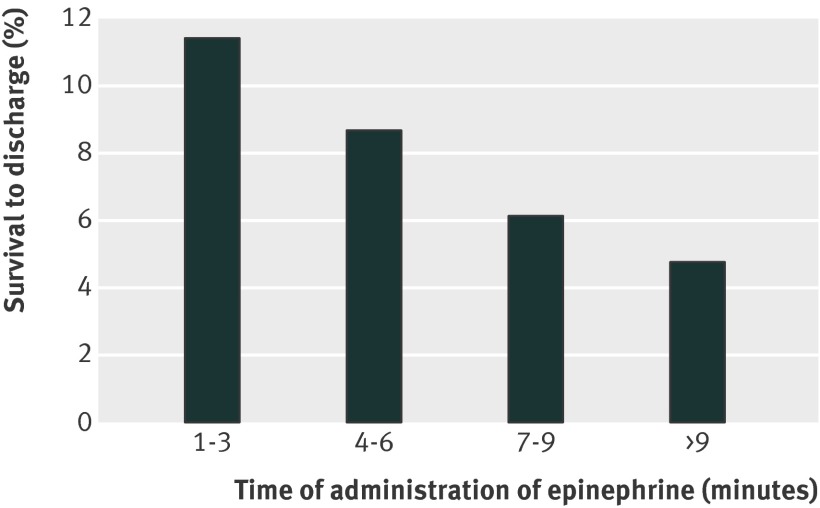

There was a stepwise decrease in survival in hospital with each additional minute of first administration of epinephrine: 929 (12%) survived when epinephrine was given in the first minute, 392 (12%) in the second minute, 305 (11%) in the third minute, 208 (9%) in the fourth minute, 335 (10%) in the fifth minute, 124 (10%) in the sixth minute, and 310 (7%) in the seventh minute or later (P<0.001). When we analyzed time to administration in three minute intervals we found a significant stepwise decrease in-hospital survival with increasing time interval, both in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (adjusted odds ratio per category: 1.0 for 1-3 minutes (reference group); 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.00; P=0.055) for 4-6 minutes; 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88; P<0.001) for 7-9 minutes; and 0.63 (0.52 to 0.76; P<0.001) for >9 minutes) (fig 2 and table 2). The stepwise decrease in outcomes was conserved across all outcome variables (see appendix 2, figs A-C).

Fig 2 Probability of survival to hospital discharge with delays in time to administration of epinephrine after cardiac arrest, with unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Table A in appendix 1 lists variables used for multivariable adjustments

Table 2.

Survival in patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest according to timing of administration of epinephrine within 3 minute time intervals after arrest

| Timing (minutes) | No (%) who survived to hospital discharge | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

| 1-3 | 1626 (12) | Reference | Reference | — |

| 4-6 | 667 (10) | 1.23 (1.12 to 1.35) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 0.055 |

| 7-9 | 180 (8) | 1.54 (1.32 to 1.81) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88) | <0.001 |

| >9 | 130 (7) | 1.77 (1.47 to 2.13) | 0.63 (0.52 to 0.76) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for variables as listed in appendix 1, table A.

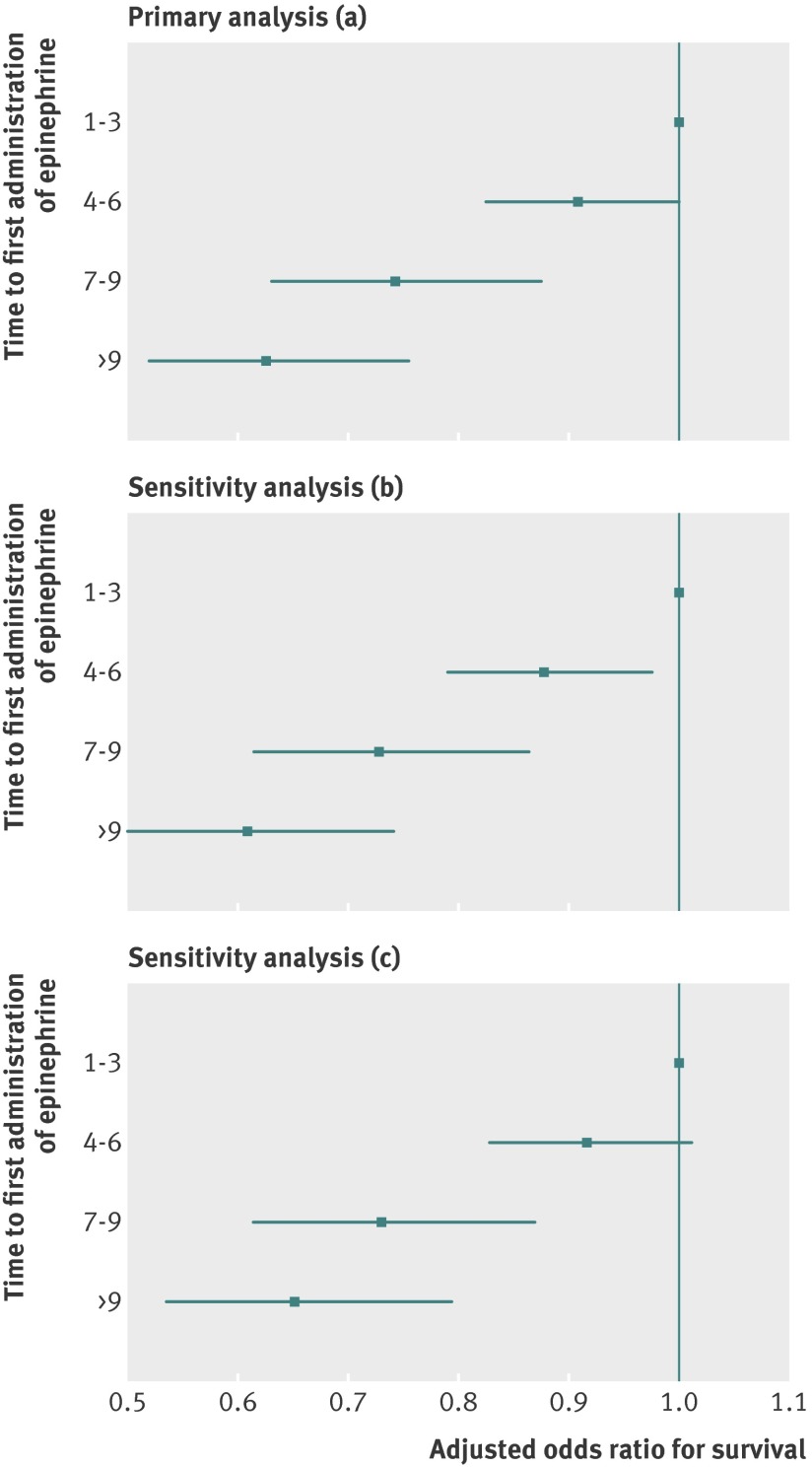

In the sensitivity analyses with adjustment for delays in initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, time to epinephrine administration remained independently associated with survival to hospital discharge after multivariable adjustments. In the first sensitivity analysis, we found that increasing time between initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and epinephrine administration was associated with a lower probability of in-hospital survival: adjusted odds ratio 1.0 for 1-3 minutes (reference category); 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.79 to 0.98; P=0.02) for 4-6 minutes; 0.73 (0.61 to 0.86; P<0.001) for 7-9 minutes; and 0.61 (0.50 to 0.74; P<0.001) for >9 minutes. In the second sensitivity analysis, which restricted the analysis to patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation within the first minute of recognition of the event (n=23 596), delay in epinephrine administration was associated with a stepwise decrease in the probability of in-hospital survival: adjusted odds ratio 1.0 (reference category) for 1-3 minutes; 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01; P=0.09) for 4-6 minutes; 0.73 (0.61 to 0.87; P<0.001) for 7-9 minutes; and 0.65 (0.53 to 0.79; P<0.001) for >9 minutes. Figure 3 shows a comparison of the results of the primary analysis and two sensitivity analyses.

Fig 3 Multivariable models to assess relation between time of administration of epinephrine and survival. Primary analysis (a): association between interval from recognition of cardiac arrest event to administration of epinephrine and in-hospital survival. Sensitivity analysis (b): association between interval from initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and administration of epinephrine and in-hospital survival. Sensitivity analysis (c): association between time to administration of epinephrine and survival in subgroup of patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation within first minute after arrest. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

In the post hoc sensitivity analysis in which patients were categorized by quarters of delivery of epinephrine there was a stepwise decrease in survival in hospital with increasing quarter: 929 (12%) in the first quarter, 697 (11%) in the second quarter, 543 (10%) in the third quarter, and 434 (8%) in the fourth quarter (P<0.001). There was a stepwise decrease in-hospital survival with increasing quarter of first epinephrine in both adjusted and unadjusted analyses (see appendix 2, fig D). In patients without complete covariate data the crude survival rates in each category of delivery of epinephrine were 13% for 1-3 minutes, 10% for 4-6 minutes, 8% for 7-9 minutes, and 9% for >9 minutes. There was no significant difference in survival rates between those with and without complete covariate data (P=0.5). Imputations carried out five times for missing covariate data showed no significant difference in the association between category of delivery of epinephrine and primary outcome (results not shown).

Discussion

Principal findings

In patients who experience a cardiac arrest in hospital, earlier administration of epinephrine is strongly associated with increased probability of return of spontaneous circulation, 24 hour survival, in-hospital survival, and overall neurologically intact survival. These associations remained robust after multivariable adjustments and were also maintained in sensitivity analyses adjusted for delays in initiation of resuscitation.

The physiologic rationale for early administration of epinephrine in patients with cardiac arrest is strong, particularly in those with rhythms not amenable to defibrillation. Epinephrine is a potent peripheral vasoconstrictor as well as a coronary artery vasodilator. This combination of physiologic effects results in an increase in coronary perfusion pressure, which has been shown to be strongly associated with return of spontaneous circulation in both animals and humans.19 20 During complete circulatory arrest and in the absence of a shockable rhythm, the administration of epinephrine would logically be a time dependent intervention.

Comparison with other studies

While little controversy exists over the ability of epinephrine to increase rates of return of spontaneous circulation, current scrutiny of this intervention has focused on whether mortality and neurologically intact survival can be improved. The current findings might provide insight into this question. One previous large scale investigation failed to show a survival benefit with the use of drugs for advanced life support in the outpatient setting.15 The mean time to arrival of emergency medical staff in that investigation, however, was 10 minutes, and epinephrine delivery was therefore delayed by virtue of arrival time alone. The lack of efficacy could have resulted from delay in time to intervention. A recent randomized trial evaluated the provision of epinephrine versus placebo for patients with out of hospital cardiac arrest.21 In this investigation, Jacobs and colleagues found that epinephrine markedly increased rates of return of spontaneous circulation, but the study was underpowered to evaluate the primary outcome of neurologically intact survival. Finally, a retrospective study in Japan suggested an increase in return of spontaneous circulation but worse long term outcome.16 Only a small fraction of patients received epinephrine, however, and selection bias could have been present despite efforts to control for this. In the context of our findings, future investigations should consider timing of epinephrine administration in design and interpretation.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective evaluation. We attempted to overcome this weakness through multiple regression modeling, and our findings were resilient to multiple modeling strategies, but it is possible that unmeasured confounding remains. We performed several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings when we considered delays in the initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. We were, however, unable to ascertain the specific reasons for delays in the arrival of advanced resuscitation teams. Second, the data were collected by various different healthcare systems throughout the country, and variability in the quality of data could potentially occur. To mitigate this weakness, the American Heart Association provides training and certification for data abstraction to ensure standardized data collection across hospitals and health systems. Further, the association performs regular reviews to ensure the accuracy and quality of the dataset. Third, data on neurologic outcomes were unavailable for a small number of patients (2%). Additionally, we were unable to assess the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in each case and whether interruptions in chest compressions were related to the outcomes.

Conclusions and policy implications

We found that shorter time to administration of epinephrine is associated with better outcomes after in-hospital cardiac arrest with a non-shockable rhythm. Our findings have important public health and policy implications. First, we found that delayed administration was associated with lower probability of survival, and this finding could help inform clinical practice and quality measurements in cardiac arrest. Currently, healthcare providers do not typically evaluate the quality of resuscitation with “time to epinephrine” as a metric in pulseless electrical activity or asystole. Rather, quality metrics have focused almost exclusively on defibrillation, leading hospital systems to allocate resources to improve the rapidity of defibrillation for cardiac arrests with shockable rhythms. To support this goal, defibrillation (once considered an “advanced skill”) has become part of basic courses in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and can be adequately applied by the lay public. Defibrillation, however, is not useful for most cardiac arrests, and, when a patient is not in a shockable rhythm, current standard of care focuses on cardiopulmonary resuscitation only, even for many healthcare providers. With such a large proportion of cardiac arrests being non-shockable rhythms, future quality metrics could conceivably focus on shortening the time to administration of epinephrine in these patients. For providers trained in advanced cardiac life support, epinephrine is part of the armamentarium, but there is a lack of focus on timing of administration of this drug. Finally, the past decade has seen a decrease in the incidence of shockable cardiac arrests, which further emphasizes the need for research and quality control measures in patients with non-shockable rhythms.8

What is already known on this topic

For patients with cardiac arrest with rhythms not amenable to defibrillation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intravenous epinephrine are the standard for resuscitation therapy

The use of epinephrine is currently under scrutiny as recent investigations have questioned its influence on long term outcomes after cardiac arrest

What this study adds

In patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest with a non-shockable rhythm, early administration of epinephrine is associated with improved outcomes including in-hospital survival and neurologically intact survival

The timing of epinephrine is important in resuscitation efforts as more favorable outcomes were observed with early delivery even after adjustment for delays in the initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation

We thank Tyler Giberson and Lars Andersen for their final review and editorial assistance and Francesca Montillo for her editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators

Besides MWD, members of the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Adult Task Force include: Paul S Chan, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute; Steven M Bradley, VA Eastern Colorado Healthcare System; Dana P Edelson, University of Chicago; Robert T Faillace, Geisinger Healthcare System; Romergryko Geocadin, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Raina Merchant, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Vincent N Mosesso Jr, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Joseph P Ornato and Mary Ann Peberdy, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Contributors: MWD: conception, design, analysis, data interpretation and manuscript writing. SG: analysis. JDS: analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing. BG: conception, design, interpretation, manuscript writing. MNC: data interpretation, manuscript writing. MDH: analysis, interpretation, extensive editorial review of manuscript. KB: interpretation, manuscript writing. CC: data interpretation, editorial review of manuscript. MWD is guarantor.

Funding: The project described was supported, in part, by grant No UL1 RR025758-Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. MWD is supported by NHLBI (1K02HL107447-01A1) and NIH (R21AT005119-01).

Competing interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required. The database is exempt from institutional review board approval as it is part of a QI registry.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Declaration of transparency: The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g3028

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-B

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A-D

References

- 1.Merchant RM, Yang L, Becker LB, Berg RA, Nadkarni V, Nichol G, et al. Incidence of treated cardiac arrest in hospitalized patients in the United States. Crit Care Med 2011;39:2401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedell SE, Delbanco TL, Cook EF, Epstein FH. Survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the hospital. N Engl J Med 1983;309:569-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebell MH, Becker LA, Barry HC, Hagen M. Survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:805-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, Carey SM, Kaye W, Mancini ME, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA 2006;295:50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Nadkarni V, Mancini ME, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14 720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003;58:297-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner SC, Sharma TK. Outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and predictors of resuscitation status in an urban community teaching hospital. Resuscitation 1994;27:13-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandroni C, Nolan J, Cavallaro F, Antonelli M. In-hospital cardiac arrest: incidence, prognosis and possible measures to improve survival. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:237-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb LA, Fahrenbruch CE, Olsufka M, Copass MK. Changing incidence of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation, 1980-2000. JAMA 2002;288:3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1912-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2008;358:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2002;346:549-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:557-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yakaitis RW, Otto CW, Blitt CD. Relative importance of alpha and beta adrenergic receptors during resuscitation. Crit Care Med 1979;7:293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122:S729-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olasveengen TM, Sunde K, Brunborg C, Thowsen J, Steen PA, Wik L. Intravenous drug administration during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2009;302:2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagihara A, Hasegawa M, Abe T, Nagata T, Wakata Y, Miyazaki S. Prehospital epinephrine use and survival among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2012;307:1161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummins RO, Chamberlain D, Hazinski MF, Nadkarni V, Kloeck W, Kramer E, et al. Recommended guidelines for reviewing, reporting, and conducting research on in-hospital resuscitation: the in-hospital “Utstein style.” Ann Emerg Med 1997;29:650-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgren E, Hedstrand U, Kelsey S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Safar P. Assessment of neurological prognosis in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Lancet 1994;343:1055-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paradis NA, Martin GB, Rosenberg J, Rivers EP, Goetting MG, Appleton TJ, et al. The effect of standard-and high-dose epinephrine on coronary perfusion pressure during prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA 1991;265:1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradis NA, Martin GB, Rivers EP, Goetting MG, Appleton TJ, Feingold M, et al. Coronary perfusion pressure and the return of spontaneous circulation in human cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA 1990;263:1106-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs IG, Finn JC, Jelinek GA, Oxer HF, Thompson PL. Effect of adrenaline on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Resuscitation 2011;82:1138-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-B

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A-D