Abstract

Background: The school-leaving GPA and the time since completion of secondary education are the major criteria for admission to German medical schools. However, the predictive value of the school-leaving grade and the admission delay have not been thoroughly examined since the amendment of the Medical Licensing Regulations and the introduction of reformed curricula in 2002. Detailed information on the prognosis of the different admission groups is also missing.

Aim: To examine the predictive values of the school-leaving grade and the age at enrolment for academic performance and continuity throughout the reformed medical course.

Methods: The study includes the central admission groups “GPA-best” and “delayed admission” as well as the primary and secondary local admission groups of three consecutive cohorts. The relationship between the criteria academic performance and continuity and the predictors school-leaving GPA, enrolment age, and admission group affiliation were examined up to the beginning of the final clerkship year.

Results: The academic performance and the prolongation of the pre-clinical part of undergraduate training were significantly related to the school-leaving GPA. Conversely, the dropout rate was related to age at enrolment. The students of the GPA-best group and the primary local admission group performed best and had the lowest dropout rates. The students of the delayed admission group and secondary local admission group performed significantly worse. More than 20% of these students dropped out within the pre-clinical course, half of them due to poor academic performance. However, the academic performance of all of the admission groups was highly variable and only about 35% of the students of each group reached the final clerkship year within the regular time.

Discussion: The school-leaving grade and age appear to have different prognostic implications for academic performance and continuity. Both factors have consequences for the delayed admission group. The academic prognosis of the secondary local admission group is as problematic as that of the delayed admission group. Additional admission instruments would be necessary, in order to recognise potentially able applicants independently of their school-leaving grade and to avoid the secondary admission procedure.

Keywords: Medical studies, admission, GPA, school leaving grades

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Die HZB Qualifikation und die Wartezeit sind die wichtigsten Zulassungskriterien für das Medizinstudium in Deutschland. Seit der Novellierung der Approbationsordnung und der Einführung von Reformcurricula wurde der Vorhersagewert der HZB Qualifikation und der Wartezeit nicht ausführlich untersucht. Ebenso fehlen detaillierte Daten über die Studienprognose der unterschiedlichen Zulassungsquoten.

Ziel: Untersuchung des Vorhersagewerts der Abiturdurchschnittsnote und des Alters für Studienleistung und Kontinuität im Verlauf eines reformierten Medizinstudiums.

Methodik: Die Studie umfasste Studierende der Abiturbesten-, AdH- und Wartezeitquote sowie des Nachrückverfahrens von drei Kohorten. Die Beziehung zwischen Studienleistung bzw. Studienkontinuität und der Abiturdurchschnittsnote, dem Studieneintrittsalter und der Zulassungsquoten-Zugehörigkeit wurde bis zum PJ-Beginn statistisch untersucht.

Ergebnisse: Die Studienleistung und die Studienverzögerungsrate im vorklinischen Studienabschnitt standen in einem signifikanten Zusammenhang mit der Abiturdurchschnittsnote. Dagegen hing die Studienabbruchsrate mit dem Studieneintrittsalter zusammen. Die Studierenden der Abiturbesten- und AdH-Quote erreichten die besten Studienleistungen und niedrigsten Studienabbruchsraten. Das Leistungsniveau der nach Wartezeit sowie im Nachrückverfahren zugelassenen Studierenden war niedriger, und mehr als 20% von ihnen brachen das Studium während des vorklinischen Studienabschnitts ab, die Hälfte davon aufgrund von Leistungsschwäche. Die Studienleistungen aller Zulassungsgruppen waren jedoch sehr variabel, und nur ca. 35% der Studierenden einer jeden Zulassungsgruppe traten das PJ in der Regelstudienzeit an.

Diskussion: Die Abiturnote und das Alter haben unterschiedliche prognostische Bedeutungen für Studienleistung und -kontinuität. Auf die Prognose in der Gruppe der Studierenden der Wartezeitquote wirken sich beide Faktoren negativ aus. Die Studienprognose der Nachrücker ist ebenso problematisch wie die der Wartezeitquote. Zusätzliche Auswahlinstrumente erscheinen notwendig, um potentiell fähige Studierende unabhängig von der Abiturnote zu erkennen und ein Nachrückverfahren zu vermeiden.

Intooduction

Student admission in Germany

The admission to German medical schools occurs via different central and local admission pathways (“quotas”). It is unique in that both pathways include both, selection by merit and admission of applicants who fail to meet the merit criteria. This is in accordance with the German constitution which guarantees free choice of profession also to applicants who do not qualify by merit. They are, however, put on a waiting list and are admitted up to six years after graduating from secondary education. Thus, age and merit of the students are mutually linked. Moreover, all of the available study places must by law be occupied. Unoccupied admission slots following the regular selection process must be filled by applicants of lower merit.

Approximately 10% of the admission slots are allocated to priority groups that do not concern the present study. Of the remaining admission slots, 20% are centrally allocated to applicants with the best school-leaving grade 1.0 (GPA; scale: 1.0-6.0, 4.0=pass), which is equivalent to the British A* and spans 768-840 points on the 840 assessment scale (GPA-best group). A further 20% of the admission slots are centrally allocated with a delay of up to six years to applicants who fail to qualify for direct admission and whose school-leaving grades usually are 2.0 (600 assessment points) or worse (delayed admission group). Following the central admission process, the remaining admission slots are allocated locally by the universities’ own admission criteria (primary local admission group). Following student registration, vacant admission slots due to declined admissions are allocated locally in a secondary admission process. Since many local applicants are centrally allocated to other universities, the secondary admission process includes applicants that originally were low on the applicants’ ranking list and whose qualifications predict relatively weak academic performance. The present study focuses on the academic progression of the students of these four admission groups.

The admission instrument School-leaving grade

The pre-university academic performance, assessed by school-leaving grades or college grades, serves as the primary admission instrument of medical schools around the world [1], [2]. Even universities that employ additional admission instruments such as in Australia [3], Great Britain [4], [5], Sweden [6], or Israel [7], pre-select their applicants by means of their school-leaving grades.

With validity coefficients ranging between 0.26-0.58 [2], [8], [9], [10], [11], the school-leaving grade is considered the most reliable predictor for success in the medical course. Its high predictive value has also been documented for other academic courses [8], [9] as well as for non-academic professions [12].

Information gaps

The prognostic validity of the German baccalaureate for success in the medical course was extensively investigated at the end of the 20th century [9], [13], and on a smaller scale also later [2], [8], primarily with respect to the first, pre-clinical part of the Medical Licensing Examination. It had values of approximately 0.5 [14]. However, it has not yet been thoroughly examined since the amendment of the German Medical Licensing Regulations from 27th June 2002 and the resulting implementation of reformed curricula [15]. It is unclear whether previously published predictive values still apply. Moreover, the predictive value of the GPA for academic performance throughout the entire medical course, especially in the clinical part of the course, has scarcely been investigated. Internal examination results have only seldom been considered as academic endpoints as exemplified by Ferguson and his co-workers [16]. The examination results in the first try have to our knowledge never been specifically used as a realistic measure of progressive academic performance. Furthermore, the differential roles of the GPA and the enrolment age in predicting the academic outcome have not been sufficiently clarified with attention to their mutual linkage under the German admission regulations.

Previous investigations of the predictive value of the German school-leaving GPA have not distinguished in detail between the direct, secondary and delayed admission groups and have not considered the possible association between academic performance and continuity of Undergraduate medical training.

The aim of the present study is, therefore, to examine the predictive value of the GPA and the age at enrolment for academic performance and continuity during the entire duration of the reformed curriculum HeiCuMed (Heidelberg Curriculum Medicinale). The study analyses the academic progress of 720 students who enrolled after the tertiary education reform from 2004. The time taken to complete the studies and the performance in the first try at each examination were used as measures for academic progress.

Methods

Participants and inclusion criteria

The participants in the study were medical students at the Heidelberg Medical Faculty who had qualified for tertiary education by the German baccalaureate and had enrolled in winter semesters 2005/2006, 2006/2007, and 2007/2008. They included the central GPA-best and delayed admission groups as well as the primary and secondary local admission groups. Students having a previous academic degree and students who had enrolled by judicial verdict were also included, but their data neglected in the major analysis due to their small numbers.

Admission criteria

The admission criteria for the different admission groups were as follows:

GPA-best group – GPA.

Delayed admission group – waiting time by number of semesters.

-

Primary and secondary local admission groups – GPA and additional “bonus criteria”:

Vocational training and professional experience in medicine-related fields (6.5% and 18.4% of the pooled primary and secondary local admission groups of the three cohorts, respectively).

Success in education-related competitions.

Voluntary social service (3.6% and 1.0% of the pooled primary and secondary local admission groups of the three cohorts, respectively).

Exclusion criteria

The following groups of students were excluded from the study:

Students who had been admitted due to their excellent performance (in addition to the GPA) in the voluntary German Aptitude Test for Medical Studies (TMS).

Admission groups with small case numbers (priority admissions, cases of hardship, admissions by lottery).

Students with deferred enrolment who had been admitted prior to the implementation of the local admission procedure in 2005 and the local documentation of the qualifying data of applicants.

Foreign students.

Data recruitment and data protection

The study was performed in connection with the quality management of the admission procedure of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty. Birth dates, registration and de-registration dates, examination results, and the date of passing the first part of the Medical Licensing Examination (M1) were retrieved from the data bank of the faculty. The school-leaving grades of the locally admitted students and of the centrally admitted students who had also applied locally were retrieved from the application files. The school-leaving grades of the remaining centrally admitted students were no longer available at the onset of the study. The data were tabulated in MS Excel® and anonymised prior to their analysis by removal of the columns that contained personal data except for age and gender. The work was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the German data protection laws.

Evaluation of academic performance

The analysis of the students’ performance was based on the results of their first try at each examination. It was assumed that the first try better reflects the actual learning performance than the repetition of failed examinations. An average result was calculated for each student and separately for the preclinical and clinical part of undergraduate training. The examination results of the clinical part were reported on the academic scale of 1.0 (best) to 5.0 (fail). The examination results of the pre-clinical part were reported on different point scales. They were then standardised and converted to the 1.0-5.0 scale. Examination results in the form of “pass/fail” were excluded from the analysis.

Evaluation of studies continuity

Dropout was determined by the date of de-registration. Since many examinations are not time-bound, regular and prolonged continuity (“deceleration”) were determined at three endpoints: the date of successfully passing the first part of the Licensing (M1) Examination, the date of passing the last internal examination that completes the academic requirements, and the date of entering the final clerkship year. The reasons for dropout and for prolongation of the studies were retrieved from the data bank of the faculty if recorded. Almost complete records were available for the factor academic difficulties.

Statistical methods

The data of the three cohorts were pooled. Basic statistics, distribution analyses, multiple and logistic regressions, Pearson correlation and partial correlation zero order analyses, two-way χ2 tests for proportions, two-tailed t-test with Bonferonni correction for multiple comparisons, confidence interval determinations with bootstrapping when applicable, and SNK-test were performed in IBM SPSS® 19 and 21. Quadratic regression was performed in MS Excel®. Graphics were generated in Excel and finished in Canvas® 10 (ACD Systems).

Results

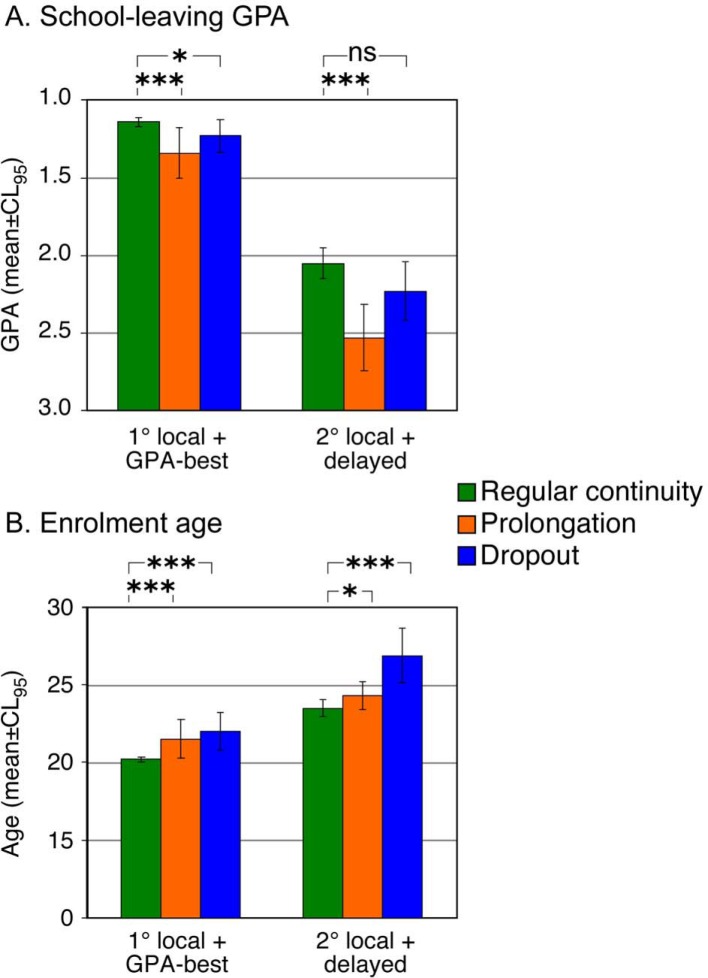

Enrolment age

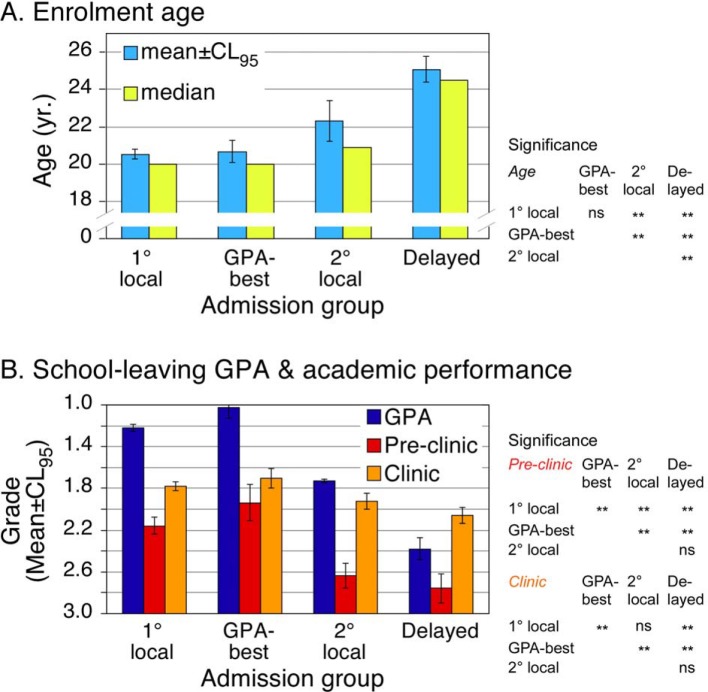

The students of the GPA-best and primary local admission groups were on average 20.5 years old at registration. The students of the secondary local admission group were 22.3 years old. The students of the delayed admission group formed a distinctly older group with a mean age of 25 years (see figure 1A (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. Enrolment age, School-leaving GPA, and academic performance of the admission groups. Significance was tested by two-tailed t-test with Bonferonni correction for multiple comparisons. Abbreviations: (Pre-clinic, Clinic) mean examination grades in the pre-clinical and clinical parts of the course; (CL95) 95%-confidence limit; (1°, 2°) primary and secondary local admission groups; (**) significance tested at α=0.01; (ns) not significant.

School-leaving GPA

Ninety-four percent of the students of the GPA-best group and 30% of the students of the primary local admission group had a GPA of 1.0. Only nine students of the delayed admission and secondary local admission groups had the GPA 1.0. On average, the students of the GPA-best group had the best school-leaving GPA. The students of the primary local admission group had on average somewhat inferior GPAs, the students of the secondary local admission group had still worse GPAs and the students of the delayed admission group had the worst GPAs (see figure 1B (Fig. 1)). The GPAs of the delayed admission group, 2.4±0.64 (mean±SD), corresponded to the national average.

The age at enrolment and the school-leaving GPA were closely associated (adjusted correlation coefficient radj=0.534) due to the dependence of the admission group affiliation on GPA.

Academic performance

In both the pre-clinical and clinical parts of undergraduate training, male and female students did not significantly differ in their performance. On average, the students of all four admission groups achieved better examination results in the clinical part of the course than in the pre-clinical part. However, with the exception of the delayed admission group, their results in the clinical part were inferior to their school-leaving grades (see figure 1B (Fig. 1)). On average, the students improved their examination marks in the clinical part by 0.44 of a grade as compared to the pre-clinical part (p<0.001). The delayed admission group achieved the best improvement (0.7) whereas the GPA-best group showed the smallest improvement (0.3; see figure 1B (Fig. 1)).

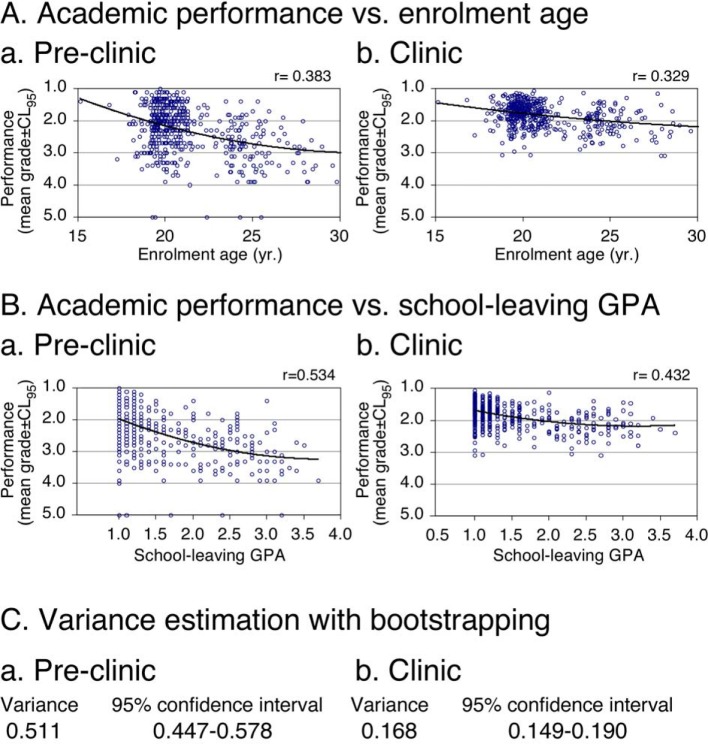

The students of the GPA-best group performed on average best in both parts of undergraduate training and were closely followed by the primary local admission group. The delayed admission group and the secondary local admission group did not significantly differ from one another with respect to their performance. Their pre-clinical examination grades were on average 0.7 to 0.8 of a grade worse than those of the GPA-best group in the pre-clinical part of the course and 0.36 worse in the clinical part (see figure 1B (Fig. 1)). Yet, among the delayed admission group and secondary local admission group there were also highly performing students and the GPA-best group included also poorly performing students. Thus, the distributions of examination results of all GPA subgroups and age subgroups overlapped (see figure 2 (Fig. 2)). The distribution range, the differences between the admission groups (see figure 1B (Fig. 1)) and the variability among the individual participants (see figure 2 (Fig. 2)) were smaller in the clinical part of the course than in the pre-clinical part.

Figure 2. Scatter diagrams and quadratic regression curves for the relationship between academic performance and enrolment age (A) or school-leaving GPA (B). (r) Correlation coefficient of the quadratic relationship between criterion and predictor.

Relative predictive value of the GPA and the age at enrolment

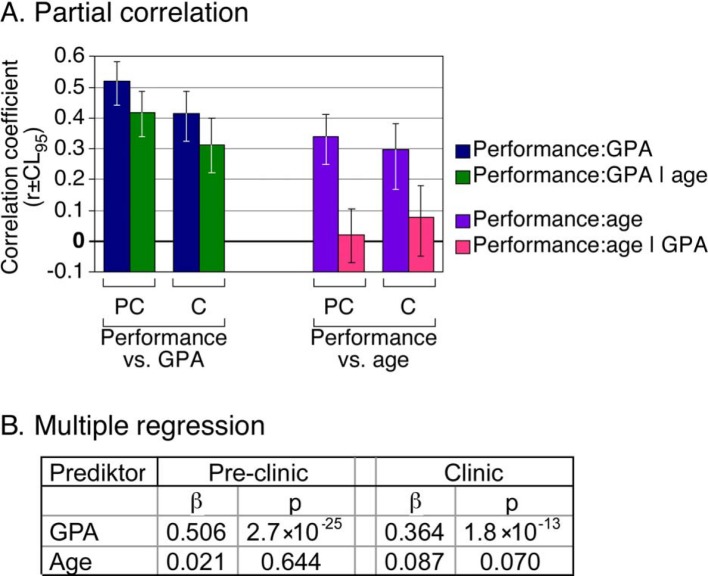

Figures 1 (Fig. 1) and 2 (Fig. 2) indicate that the GPA and the enrolment age are mutually linked, and that academic performance is associated with both these variables. Therefore, the relative prognostic value of the GPA and the enrolment age for academic performance was examined by partial correlation and multiple regression (see figure 3 (Fig. 3)).

Figure 3. Partial prognostic value of school-leaving GPA and enrolment age for academic performance. A. Correlation between academic performance and school-leaving GPA (Performance:GPA) under control of enrolment age (Performance:GPA | age) as well as correlation between academic performance and enrolment age (Performance:age) under control of school-leaving GPA (Performance:age | GPA). PC=preclinic, C=clinic B. Partial standardised regression coefficients (β).

The correlation between academic performance and GPA was slightly reduced under the control of enrolment age. In contrast, the correlation between academic performance and enrolment age was reduced to insignificance under the control of GPA (see figure 3A (Fig. 3)). In agreement with this finding, multiple regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between academic performance and GPA whereas the relationship between academic performance and enrolment age was not significant (see figure 3B (Fig. 3)).

Continuity of studies progression

With respect to the third (last) cohort, the study proceeded for 4½ years after the regular date for passing the M1 examination, 1½ years after the regular time for completion of all faculty examinations, and one year after the regular date for entering the clerkship year. For the second and first cohorts these intervals were one and two years longer, respectively. The long observation time enabled the reliable documentation of the prolongation of studies.

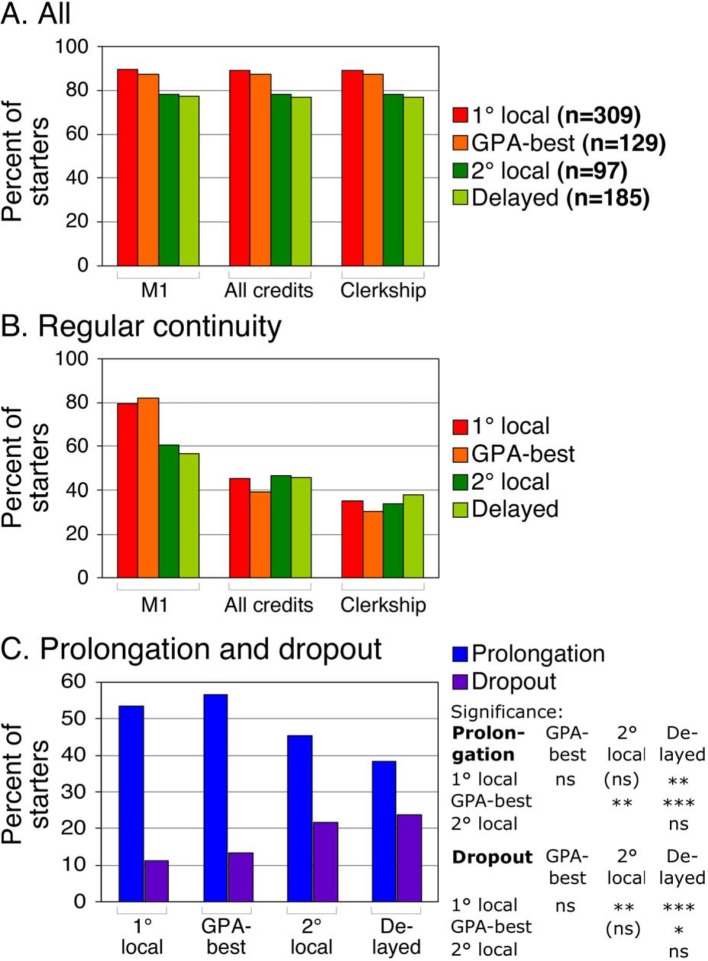

Eighty-nine point three percent of the students of the primary local admission group, 87.5% of the GPA-best group, 78.4% of the secondary local admission group, and 76.6% of the delayed admission group entered the clerkship year within the observation period (see figure 4A (Fig. 4)). All of the students who dropped out prematurely did so at the end of the pre-clinical part of the course or earlier, so that the number of students reaching the final clerkship year was almost identical to the number of students who successfully passed the M1 examination (see figure 4A (Fig. 4)).

Figure 4. Studies continuity of the different admission groups. Continuity was assessed at the following end-points: passing the first part of the Medical Licensing Examination (M1), the completion of all prescribed courses (all credits) and the beginning of the clerkship year. A. Percentage of the enrolled students (starters) of the different admission groups who reached the given end-points during the investigation. B. Percentage of the starters who reached the given end-points in the prescribed (regular) time. C. Percentage of the starters, who prolonged their studies or dropped out prematurely. The significance of the differences was tested by χ2-test for binomial proportions. Abbreviations: (All) all students over the complete course; (1°, 2°) primary and secondary local admission groups; (***) p≤0.001; (**) p≤0.01; (*) p≤0.05; ((ns)) 0.05<p≤0.10; (ns) not significant.

The proportions of students of the different admission groups who completed each part of the course within the prescribed time varied considerably. The proportions of students of the secondary local admission group and the delayed admission group who passed the M1 examination in the prescribed time (almost 60%) was approximately 25% smaller than the respective proportions of the GPA-best and primary local admission groups (see figure 4B (Fig. 4)). Conversely, the percentage of the students of the primary local admission group (34%) and the GPA-best group (43%) who prolonged their clinical studies were three to four times higher than in the secondary local admission group (14.4%) and the delayed admission group (10.9%). Consequently, similar proportions of all four admission groups completed the academic part of the course (39-46%) and entered the clerkship year (30-38%) within the prescribed time (see figure 4B (Fig. 4)).

Altogether, the percentage of students who dropped out was larger in the secondary local admission group and the delayed admission group than in the GPA-best group and the primary local admission group. On the other hand, the proportion of the students who prolonged their studies was larger in the GPA-best group and the primary local admission group than in the secondary admission group and the delayed admission group (see figure 4C (Fig. 4)).

The proportion of students who prolonged their studies or dropped out enabled predictions about the probability of the prolongation of studies and dropout. However, due to the different sizes of the different admission groups (see figure 4C (Fig. 4)) their nominal contribution to student loss varied. Of the three pooled cohorts, 33 students of the primary local admission group, 17 of the GPA-best group, 21 of the secondary local admission group, and 43 students of the delayed admission group dropped out. In addition, 32 students of the primary local admission group, 7 of the GPA-best group, 17 of the secondary local admission group, and 38 students of the delayed admission group had prolonged their studies and thereby left their original cohorts.

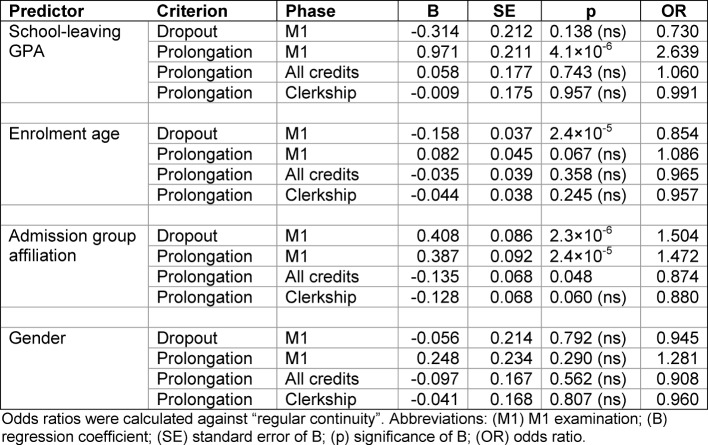

Predictors for the prolongation of studies and dropout

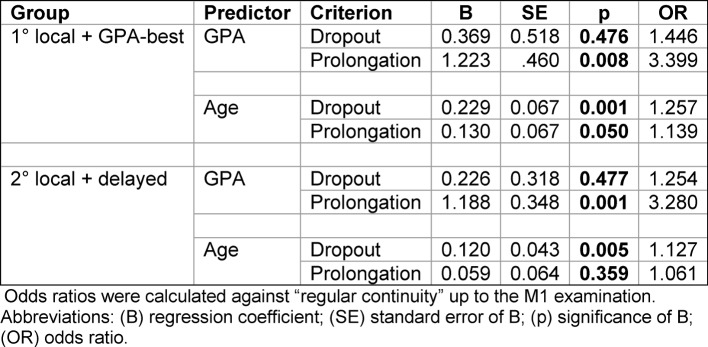

The predictive value of the GPA, the enrolment age, the admission group affiliation, and the gender for dropout and the prolongation of studies were examined by binary logistic regression (see table 1 (Tab. 1)). By this analysis, the probability of prolonging the pre-clinical studies is significantly influenced by the GPA (odds ratio, OR=2.639) and the risk of dropping out during the pre-clinical part of the course is significantly influenced by the enrolment age (OR=0.854). The admission group affiliation significantly influences both the risk for dropout (OR=1.504) and the prolongation of studies (OR=1.472) in the pre-clinical part of the course as well as the prolongation of studies in the clinical part of the course (OR=0.874). Neither prolongation nor dropout appeared to be associated with gender differences (see table 1 (Tab. 1)).

Table 1. Logistic regression of the relationship between dropout or prolongation of studies and school-leaving grade, enrolment age, admission group affiliation, and gender.

For a more differentiated analysis, the influences of GPA and enrolment age on academic performance and continuity in the pre-clinical part of the course were separately examined. To this end, the primary local admission and the GPA-best groups as well as the secondary local admission and delayed admission groups were pooled (see table 2 (Tab. 2)). The GPA strongly influenced the probability of the prolongation of studies in both pooled groups (OR=3.280) but had no significant influence on dropout. In contrast, the enrolment age had moderate but significant influence on both criteria in the pooled primary local admission + GPA-best group. In the pooled secondary local admission + delayed admission group, enrolment age significantly influenced the probability of dropping out but not the probability of prolonging the studies (see table 2 (Tab. 2)).

Table 2. Logistic regression of the relationship between dropout or prolongation of studies and school-leaving GPA and enrolment age in the pooled admission groups, primary (1°) local admission + GPA-best and secondary (2°) local admission + delayed admission in the pre-clinical part of the course.

To control the results of the logistic regression, the GPAs and the enrolment age of the students who passed the M1 examination in the prescribed time or with delay or who dropped out prior to the M1 examination were examined in the two pooled groups (see figure 5 (Fig. 5)). The GPAs of the students who prolonged the studies were significantly worse than the GPAs of the students who passed the M1 examination in the prescribed time, whereas the GPAs of the students who dropped out were only slightly but insignificantly worse than the GPAs of the latter group. Conversely, the students who prolonged their studies were only slightly older, the students who dropped out were considerably older at enrolment than the students who passed the M1 examination in the prescribed time. These findings conform to the results of the logistic regression although positive but insignificant odds ratios partly corresponded to marginally significant differences in figure 5 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. School-leaving GPA and enrolment age of the students who passed the M1 examination in the prescribed time (regular continuity) or later (prolongation) or dropped out prior to this examination. The admission groups were pooled as shown under the graphs. Abbreviations: (***) p≤0.001; (*) p≤0.05; (ns) not significant.

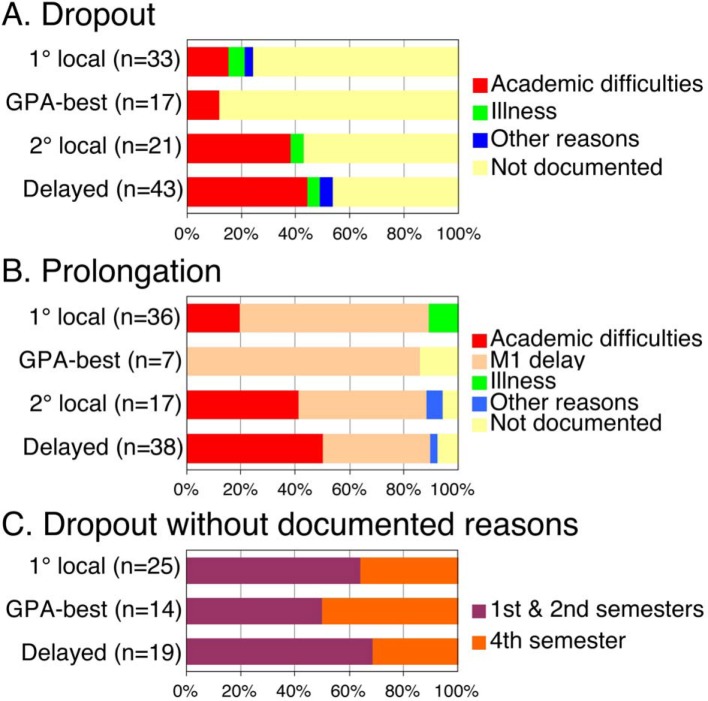

Reasons for the prolongation of studies and dropout

The early withdrawal from the course of 19 out of 43 students of the delayed admission group who dropped out was associated with academic difficulties. Similarly, 19 of the 38 students of the delayed admission group who took longer to complete the pre-clinical part of the course prolonged their studies due to academic difficulties (see figures 6A, 6B (Fig. 6)). Academic weakness was also the cause for the dropout and prolongation of studies of 15 out of 38 students of the secondary local admission group, 12 out of 69 students of the primary local admission group, and two out of 24 students of the GPA-best group, who quit or prolonged the studies in the pre-clinical part of the course (see figures 6A, 6B (Fig. 6)). Health problems were documented as the reason for prolongation or dropout of nine students.

Figure 6. Reasons for dropout and prolongation of studies in the pre-clinical part of the course. A. and B. Relative distribution of the documented reasons for dropout and prolongation. (Other reasons) documented financial und family-related reasons including pregnancy; M1-delay: differentiation between voluntary delay and delay due to academic difficulties was not possible; C. dropout time of cases whose reasons for dropping out were not documented.

For the majority of the dropouts no reasons have been documented in the data bank of the faculty. Most of them left the course already in its first year, 25 of them already by the middle of the first semester. The rest dropped out at the end of the second year (see figure 6C (Fig. 6)). The majority of the students who entered the clinical part of the course with delay had passed the pre-clinical internal examinations within the prescribed time but passed the M1 examination with delay (see figure 6B (Fig. 6)).

The prolongation of studies in the clinical part of the course including the delayed beginning of the clerkship year was only rarely associated with academic difficulties. The lessons-free semester that should be devoted to the doctoral thesis could also be used as a time buffer. Terms abroad were the most frequent reason for the prolongation of this part of the course. The remaining reasons have not been systematically surveyed but included visiting more optional courses than required, prolonged work on the doctoral thesis, parallel study courses, parallel jobs, and familial circumstances.

Additional admission groups of German students

The three investigated cohorts included 14 students who had a previous academic degree and had been admitted as “second degree students”. Six students of this group dropped out in the pre-clinical and one dropped out in the clinical part of the course. Another three students prolonged their studies. The students of this group who adhered to the course have achieved on average the grades 2.7 and 2.0 in the pre-clinical and clinical parts of the course, respectively.

Twenty-three students had been admitted due to a court verdict. Seven (30%) of these students dropped out – five of them due to academic difficulties in the pre-clinical part of the course or three times failing the M1 examination. Eight (35%) of these students prolonged their studies – three due to academic difficulties, two due to delayed passing of the M1 examination, and two due to prolonged work on their doctoral thesis. The students of this group who adhered to the course achieved on average the grades 3.1 and 2.1 in the pre-clinical and clinical parts of the course, respectively.

Discussion

The present data suggest that

the academic performance of the cohorts in question is directly associated with the school-leaving GPA, whereas adherence to the course is rather associated with the age at enrolment;

the prognosis of the secondary local admission group for academic performance and continuity is similar to that of the delayed admission group; the prognosis of both groups is worse than that of the primary local admission group and the GPA-best group;

the academic performance in the clinical part of the course is generally better than the academic performance in the pre-clinical part of the course;

considering the high variability in the academic performance of students sharing the same GPA, additional admission instruments are required in order to facilitate better identification of potentially competent applicants.

GPA and age as predictors of successful studies

The 20:20:60 regulation (GPA-best:delayed admission:local admission) determines that the school-leaving grade is the single applied predictor for studies progression for 40% of the medical students and the major predictor for 60% of the students. For this reason the present study focussed on the predictive value of the school-leaving grade and the progress of students from the different admission groups during undergraduate training. The findings agree with previous reports and show that also in the reformed curriculum the school-leaving grade is a meaningful predictor for academic performance and older students perform less well than young ones. By examination of the three cohorts this general observation could be further differentiated: The school-leaving grade appears to have significant prognostic importance for the prospective assessment of academic performance and the prolongation of studies in the pre-clinical part of training but not for dropout or overall time taken to complete the course. The dropout risk is associated with the age at the beginning of training, which in contrast to the GPA neither significantly predicts the probability of prolonging the training nor the level of academic performance. Hence, in the context of the German admission regulations, the weaker academic performance of the older students is probably related to their inferior GPAs rather than to their age.

Delayed admission and enrolment age

The students of the delayed admission group usually acquire a profession prior to their admission to medical school and have professional experience – often in the healthcare system. Many medical schools give applicants in the selection process bonus merit points for accomplished vocational training and experience in healthcare. To our knowledge, the advantage of previous professional experience for medical studies has not been systematically investigated. It is, however, plausible that previous experience in healthcare would be beneficial to doctors who pursue a medical career in a field they are also familiar with from a different perspective than that of the physician.

Some of the students of the delayed admission group have reached quite high levels of academic performance and consistently completed each part of the course in the prescribed time. It would be advantageous to recognise such potential students directly after leaving school. In general, both on account of the school-leaving grade and due to age the prognosis of the delayed admission group is less favourable than that of the other admission groups.

The high dropout rate (20%) of the delayed admission group as observed in the present study was similar to that reported from Hamburg [17]. It was statistically more strongly associated with age and the admission group affiliation than with the school-leaving grade, although almost half of the dropouts of this admission group left the course in connection with poor academic performance. It is possible that their weak academic performance was related to age-dependent life circumstances rather than to earlier performance at school. In a comprehensive analysis of the reasons for dropping out from tertiary education Heublein and his co-workers [18], [19] have shown that delayed enrolment is a major risk factor for success and continuity in the medical course. The risk is especially high when socioeconomic factors and familial circumstances make it necessary to earn money at the expense of study time. Moreover, having alternative professional qualifications may facilitate professional re-orientation (ibid.).

The prolongation of the pre-clinical studies was associated with the admission group affiliation but contrary to drop-out it was more strongly related to the school-leaving grade than to the age. The proportion of the students of the delayed admission group who prolonged their studies already at this early stage was distinctly higher than in the GPA-best group and the primary local admission group, and half of them prolonged their studies in connection with insufficient academic performance.

It appears likely that poor academic performance of students of the delayed admission group has different causes. On the one hand it is presumably affected by age-related factors such as financial self-support and on the other hand it may be associated with their level of cognitive competence. Should these assumptions be confirmed in the future, it would be reasonable to employ selective measures also for this group while in addition to support potentially competent, delayed-admission students whose academic success would otherwise be limited by their life situation.

All of the students of the delayed admission group who had reached the clinical part of the undergraduate training continued and reached without exception the final clerkship year. The tendency to prolong the studies changed: a considerably smaller proportion of the delayed admission group took longer than prescribed to complete the clinical part of the course than the respective proportion of the GPA-best group and the primary local admission group. The most frequent reasons for prolonging this part of the course were terms abroad, extended doctoral theses and visiting additional optional courses. It can be assumed that older students are inclined to refrain from such “extras” in order to finish the studies as early as possible.

Secondary local admission

The progress of students of the secondary local admission group during undergraduate training resembled that of the delayed admission group with respect to all of the examined parameters – academic performance, prolongation of studies and dropout rate. Similar too was the frequent association of prolongation and dropout during the pre-clinical part of the training with academic difficulties.

The secondary local admission group includes students who failed to be admitted to any other university in the primary admission process, but by law had to be admitted to fill in unoccupied admission slots. Their enrolment age and school-leaving grades are between those of the GPA-best/primary local admission groups and those of the delayed admission group. Whether the differences in age and GPA between the secondary and primary local admission groups suffice to explain the inferior performance and continuity of the secondary local admission group remains a matter for further investigations. It is possible that motivational factors are involved in addition to the cognitive and age-related factors.

The data indicate that the secondary local admission procedure reduces the general level of performance of the respective cohort and increases the number of dropouts. In contrast to the delayed admission procedure, the secondary local admission procedure is not legally obligatory. It can be avoided, for example, by limiting the number of university choices in the applications and correctly estimating the number of surplus offers (“overbooking”) in the primary local admission process to account for declined offers. These measures are at the discretion of the university.

Primary local admission vs. GPA-best admission

The students of the primary local admission group had been selected by their school-leaving grades and to a small extent also by bonus criteria. Their average academic performance was slightly lower than that of the GPA-best group. The difference can be explained solely by the difference between the average school-leaving grades of the two groups. By contrast, the primary local admission group has shown somewhat better continuity than the GPA-best group. A possible explanation for this is that some of the students with the best GPA, 1.0, are still uncertain about their preferred choice of academic course at the time of their first enrolment. However, in light of the small number of these cases this interpretation awaits clarification by future research.

Second course of studies and admission by lawsuit

The analysis of the academic performance and the continuity of the students who study medicine after graduating from a previous course of tertiary education and of students who acquired their study place by legally suing the university are limited by the small number of cases. However, it reveals a trend that should be looked at more closely in the future. There were successful students in both groups. Yet, in general the academic performance and continuity of both these groups were at best on a similar level as seen in the delayed admission group. Their relatively weak performance, high dropout rates and frequent prolongation of their pre-clinical studies may indicate that their ability to meet the demands of the course is inferior even to that of the delayed admission group.

Clinical vs. pre-clinical part of undergraduate training

The academic performance of all four admission groups was generally better in the clinical part of undergraduate training than in the preceding pre-clinical part. The maximal increase was achieved by the delayed admission group and the secondary local admission group, although their level of performance still remained below the level of the students with the best school-leaving grades. Several factors may have contributed to this increase in academic performance including the withdrawal of the weaker students prior to the M1 examination. Previous reports have established that the relationship between academic performance and school-leaving grades is weaker in the clinical part of training than in the pre-clinical part [9], [20]. The factors that may contribute to this increase in academic performance include the closer orientation of the clinical curriculum to the professional life in health-care [21] and the satisfaction of the students with the reformed curriculum of the clinical part of the course [22], [23], [24]. Student evaluations suggest that interest and active participation in the course are dominant factors that contribute to subjective knowledge acquisition in the reformed curriculum [25].

Conclusion

The prognostic success of the differential student admission procedure that is primarily based on school-leaving grades, to which substantial predictive importance is attached by the current German law, is limited by several factors:

The school-leaving grade explains less than 30% of the variance of academic performance, so that the variation of examination grades of students sharing the same GPA is large. Consequently, it would be beneficial to admit potentially successful candidates with a wide spectrum of school-leaving grades at the expense of applicants having top school-leaving grades but low potential for academic aptitude. This aim can be reached by employment of additional admission instruments that are independent of the school-leaving grade.

The delayed admission by waiting time and renunciation of merit-assessing predictors is problematic. Yet, rejecting potentially able students with life and work experience but mediocre school-leaving grades would also be counter-productive. Thus, it would seem advisable to apply suitable selection instruments also to the delayed admission.

The secondary admission is similar to the delayed admission with respect to the prognosis of academic performance and continuity. It should be avoided when possible.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Anna Kirchner, Dagmar Schweinfurth, Alexandra Keinert, Martina Damaschke, and Dr. Ariunaa Batsaikhan for their excellent technical support. The authors are also indebted to Anna Kirchner for her patient advice concerning student admission procedures.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2002;324:952–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hampe W, Hissbach J, Kadmon M, Kadmon G, Klusmann D, Scheutzel P. Wer wird ein guter Arzt? Verfahren zur Auswahl von Studierenden der Human- und Zahnmedizin. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2009;52:821–830. doi: 10.1007/s00103-009-0905-6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-009-0905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards T. Medical schools in Australia. Stanmore, Middlesex: Thames Digital Media; 2003. [cited 8. Dezember 2011]. Available from: http://www.medical-colleges.net/medical.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arulampalam W, Naylor RA, Smith J. Doctor who? Who gets admission offers in UK medical schools. Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit – Institute for the Study of Labor. IZA DP 1775. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McManus C, Woolf K, Dacre JE. Even one star at A level could be "too little, too late" for medical student selection. BMC Med Ed. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-16. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10,1186/1472-6920-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Löfgren K. Validation of the Swedish university entrance system. Selected results from the VALUTA-project 2001-2004. EM no. 53. Umeå: Umeå University, Department of Educational Measurement; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern N, Bentov-Gofrit D, Matot I, Abramowitz MZ. The effect of integration of non-cognitive parameters on medical students' characteristics and their intended career choices. Israel Medic Assoc J. 2011;13(8):488–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold A, Souvignier E. Prognose der Studierfähigkeit. Ergebnisse aus Längsschnittanalysen. Z Entwicklungspsychol Pädagog Psychol. 2005;37(4):214–222. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637.37.4.214. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.37.4.214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trapmann, S, Hell B, Weigand S, Schuler H. Die Validität von Schulnoten zur Vorhersage des Studienerfolgs – eine Metaanalyse. Z Pädagog Psychol. 2007;21(1):11–27. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652.21.1.11. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.21.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvatori P. Reliability and validity of admission tools used to select students fort he health professions. Adv Health Sci Edu. 2001;6(2):159–175. doi: 10.1023/A:1011489618208. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1011489618208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson D, Zhang J, Byrne GJ, Luke H, Ozolins IZ, Parker MH, Peterson RF. Medical school selection criteria and the prediction of academic performance. Evidence leading to change in policy and practice at the university of Queensland. Med J Austral. 2008;188(6):349–354. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth PL, BeVier CA, Switzer FS, III, Schippmann JS. Meta-analysing the relationship between grades and job performance. J Appl Psychol. 1996;18(5):548–556. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.5.548. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.5.548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trost G, Blum F, Fay E, Klieme E, Maichle U, Meyer M, Nauels HU. Evaluation des Tests für medizinische Studiengänge (TMS): Synopse der Ergebnisse. Bonn: Institut für Test- und Begabungsforschung; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hell B, Trapmann S, Schuler H. Eine Metaanalyse der Validität von fachspezifischen Studierfähigkeitstests im deutschsprachigen Raum. Empir Pädagog. 2007;21(3):251–270. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikendei C, Weyrich P, Jünger J, Schrauth M. Medical education in Germany. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):591–600. doi: 10.1080/01421590902833010. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590902833010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson E, Sanders A, O'Hehir F, James D. Predictive validity of personal statement and the role of the five factor model of personality in relation to medical training. J Occ Org Psychol. 2000;73:321–344. doi: 10.1348/096317900167056. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/096317900167056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampe W, Hissbach J. Kein Ersatz für die Abiturnote. Dtsch Ärztebl. 2010;107(26):A1298–A1299. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heublein U, Hutzsch C, Schreiber J, Sommer D, Besuch G. Ursachen des Studienabbruchs in Bachelor- und in herkömmlichen Studiengängen. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung von Exmatrikulierten des Studienjahres 2007/08. Hannover: HIS Hochschul-Informations-System GmbH; 2010. [cited 31. Jan 2014]. Available from: http://www.his.de/pdf/pub_fh/fh-201002.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heublein U, Spangenberg H, Sommer D. Ursachen des Studienabbruchs. Analyse 2002. Hannover: HIS Hochschul-Informations-System; 2003. [cited 31. Jan 2014]. Available from: http://www.bmbf.de/pub/ursachen_des_studienabbruchs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reede JY. Predictors of success in medicine. Clin Orthop Rel Research. 1999;362:72–77. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199905000-00012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199905000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mäkinen J, Olkinuora E, Lonka K. Students at risk: Students' general study orientations and abandoning/prolonging the course of studies. High Educ. 2004;48:173–188. doi: 10.1023/B:HIGH.0000034312.79289.ab. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000034312.79289.ab. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieberman SA, Ainsworth MA, Asimakis GK, Thomas L, Cain LD, Mancuso MG, Rabek JP, Zhang N, Frye AW. Effects of comprehensive educational reforms on academic success in a diverse student body. Med Educ. 2010;44(12):1232–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03770.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Veken J, Valcke M, De Maeseneer J, Derese A. Impact of the transition from a conventional to an integrated contextual medical curriculum on students' learning patterns: A longitudinal study. Med Teach. 2009;31(5):433–441. doi: 10.1080/01421590802141159. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590802141159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadmon G, Schmidt J, De Cono N, Büchler MW, Kadmon M. A model for persistent improvement of medical education as illustrated by the surgical reform curriculum HeiCuMed. GMS Z Med Ausb. 2011;28(2):Doc29. doi: 10.3205/zma000741. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadmon G, Schmidt J, De Cono N, Kadmon M. Integratives versus traditionelles Lernen aus Sicht der Studierenden. GMS Z Med Ausb. 2011;28(2):Doc28. doi: 10.3205/zma000740. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]