Abstract

Infectious esophagitis may be caused by fungal, viral, bacterial or even parasitic agents. Risk factors include antibiotics and steroids use, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, malignancies and immunodeficiency syndromes including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Acute onset of symptoms such as dysphagia and odynophagia is typical. It can coexist with heartburn, retrosternal discomfort, nausea and vomiting. Abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss and even cough are present sometimes. Infectious esophagitis is predominantly caused by Candida species. Other important causes include cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus infection.

Keywords: infectious esophagitis, impaired immunity, Candida, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Candida-induced esophagitis

Esophagitis is predominantly caused by noninfectious conditions, mainly gastroesophageal reflux disease [1]. Generally, infectious esophagitis occurs in patients with impaired immunity.

Although Candida is considered normal flora in the gastrointestinal tract of humans, it can cause disease when an imbalance exists. Generally different Candida species can create clinical syndromes, although infection with C. albicans is the most common. It seems to be important to identify the type of yeast because some species are more resistant to antifungal agents than others. Local, oropharyngeal candidiasis is a common infection seen particularly in infants or older adults who wear dentures, patients treated with antibiotics, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy to the head and neck, and those with immune deficiency states, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [2–4]. Patients treated with inhaled steroids are also at risk. The usual symptoms of oropharyngeal candidiasis are loss of taste, and pain during eating and swallowing or when patients try to wear their dentures. Interestingly, many patients are asymptomatic.

The diagnosis is usually made upon the presence of white plaques in the oral cavity mucosa or under dentures, where there is usually erythema without plaques. The diagnosis is confirmed by performing a Gram stain or KOH preparation on the scrapings which reveals yeasts usually with pseudohyphae.

Esophageal candidiasis is most common in patients with hematologic malignancies, steroid use or AIDS. Interestingly, concomitant thrush is or is not present, which means that the absence of thrush does not preclude the diagnosis of esophagitis [5, 6].

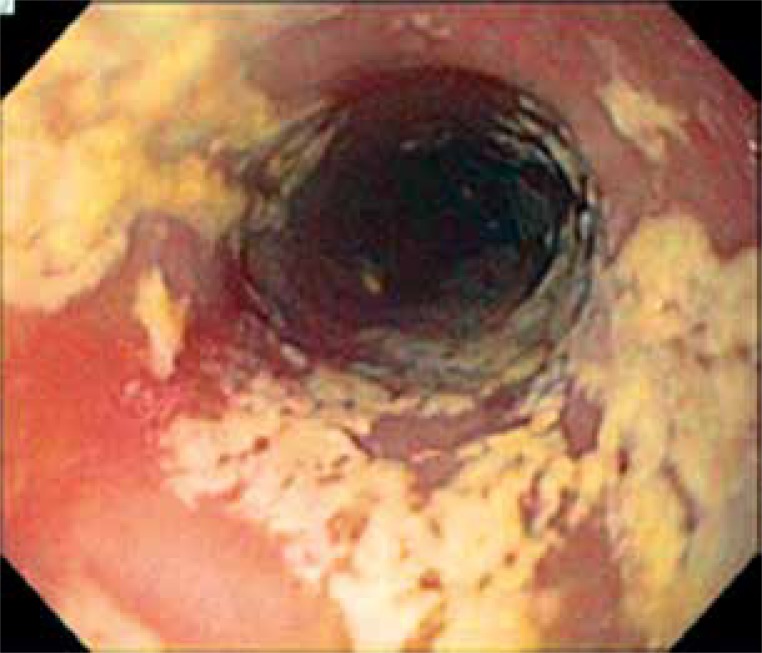

A characteristic feature of Candida esophagitis is odynophagia or retrosternal pain on swallowing. The diagnosis of Candida esophagitis is usually made when white mucosal plaque-like lesions are seen on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Candida-induced esophagitis

Confirmatory biopsy shows the presence of yeast and pseudohyphae with invasion of mucosal cells. An alternative diagnostic approach, particularly useful in AIDS patients, is to treat with systemic antifungal agents on the basis of the patient’s history. Odynophagia due to candidiasis should improve within a few days. If symptoms do not improve within 3– 5 days, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy must be performed because of high risk of coinfection. The probability of viral coinfection is even almost 50%. Cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus infections are encountered in the HIV-infected patient with advanced AIDS when the CD4 count is < 200 cells/μl [7].

The most common agent of candidiasis is C. albicans, although other species are occasionally found. Cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and aspergillosis have occasionally been described. The differential diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis includes viral infectious etiologies, but also medication-induced esophagitis, and conditions such as eosinophilic esophagitis.

The duration of oropharyngeal candidiasis treatment is 1 to 2 weeks. Interestingly, not every patient with a clinical response will achieve a mycological one. Considerations for the choice of candidiasis treatment include mainly severity of infection, drug effectiveness, ease of administration and cost. The treatment of first oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients without AIDS involves local antifungal lozenges or solutions of nystatin 600 000 U four times daily or clotrimazole 10 mg five times daily. For topical medicines, effectiveness of therapy depends on adequate contact time between the drug and the oral mucosa. If the patient does not respond to topical treatment, the preferred therapy is oral fluconazole: 200 mg loading dose, then 100 to 200 mg daily [8]. Clinical symptoms resolve in more than 90% of patients using this therapy. Studies show that the clinical and mycological response is better with fluconazole than nystatin and even oral itraconazole. Interestingly, a solution of itraconazole, but not capsules, is as effective as fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis and more effective than topical therapy with clotrimazole [9]. Recurrence is a frequent problem if underlying risk factors such as steroid use or chemotherapy are still present. In these patients prophylactic therapy with 100 mg fluconazole once daily seems to be the preferred solution.

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the most common problem in HIV-infected patients. It usually coexists with significant immunosuppression – CD4 counts < 200 cells/ml. The treatment of first oropharyngeal candidiasis in this group of patients also can involve local antifungal lozenges or solutions of nystatin or clotrimazole, but in general oral fluconazole is probably a better option, especially in patients who are at risk of developing esophageal candidiasis – CD4 count < 100 cells/μl [4, 10, 11]. Posaconazole 400 mg twice daily for 3 days followed by 400 mg once daily is an alternative azole in patients with refractory disease with extended-spectrum and in vitro activity against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. krusei [12]. There are only limited data on the use of voriconazole, although its efficacy for esophageal candidiasis suggests that it would be successful therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis.

Esophageal candidiasis is mostly secondary to C. albicans infection. The risk of disease is increased in patients with advanced immunosuppression, patients who are taking inhaled corticosteroids and individuals with cancer. This kind of esophagitis requires systemic, never local antifungal therapy [13]. An empiric antifungal therapy is appropriate in this group of patients with symptoms of odynophagia or dysphagia. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy can be performed if symptoms do not improve after approximately 3 days [14]. The duration of treatment is 2 to 3 weeks. Intravenous therapy may be required initially in patients with severe disease who cannot take oral therapy. The recommended drug is oral fluconazole with a loading dose of 400 mg followed by 200 to 400 mg once daily for 2 to 3 weeks, but in refractory cases we can use other azoles such as posaconazole, voriconazole or itraconazole in solution form [8]. Other medicines including echinocandins or amphotericin B are also acceptable. A special clinical indication for amphotericin B therapy is esophageal candidiasis during pregnancy [8]. Azoles are teratogenic and should not be used, particularly during the first trimester of pregnancy [15]. Unfortunately, there are no data regarding the use of echinocandins in pregnancy. In general, a short course of azole therapy in esophageal candidiasis rarely results in significant adverse effects. Gastrointestinal symptoms are most frequently reported, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Herpes simplex virus-induced esophagitis

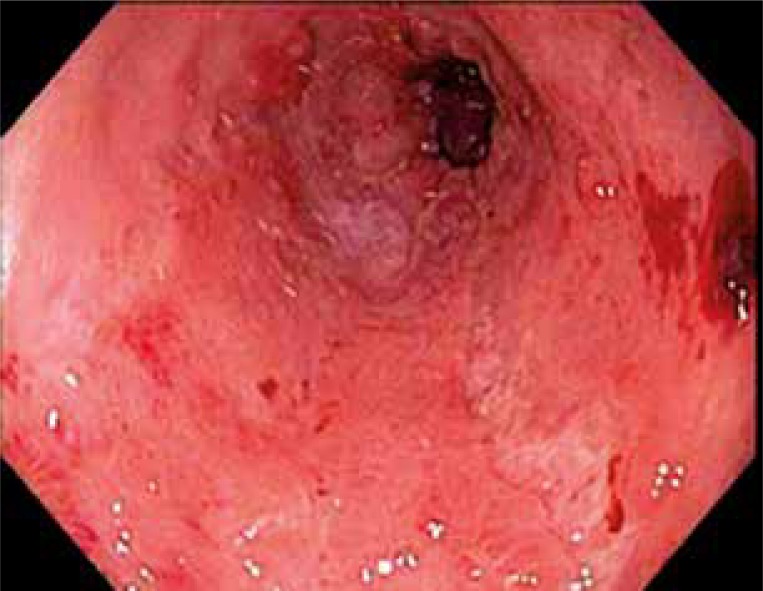

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the esophagus is usually observed in patients with an impairment of immunity, but can occasionally be seen in healthy hosts. That is mostly related to HSV type 1, although HSV-2 has also been reported [16]. HSV esophagitis occurs most frequently in solid organ and bone marrow transplant recipients [17, 18]. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis usually is a consequence of reactivation of HSV with spread of virus to the esophagus through the vagus nerve or by direct extension of infection from the oral cavity into the esophagus. Patients usually complain about odynophagia and/or dysphagia. Fever and retrosternal chest pain can be present in about 50% of individuals. Patients also can have coexistent herpes labialis or oropharyngeal ulcers [19]. The diagnosis of herpes simplex virus esophagitis is usually based on endoscopic findings confirmed by histopathological examination. Lesions which usually form ulcers less than 2 cm involve the mucosa of the distal esophagus. These ulcers are well circumscribed and have a “volcano-like” appearance; diffuse erosive esophagitis may also be present. Biopsies should be taken from the edge of an ulcer where viral cytopathic action is most likely to be seen. Histologic findings include multinucleated giant cells, with ground-glass nuclei and eosinophilic inclusions. Immunohistochemical examination for HSV glycoproteins may also be helpful [19] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HSV-induced esophagitis

The treatment of HSV esophagitis depends on the patient’s underlying immune condition. Spontaneous resolution usually occurs after 1 to 2 weeks in patients without impaired immunity, although some may respond more quickly if treated with a short course of oral acyclovir 200 mg five times a day or 400 mg three times a day for 1 to 2 weeks. Patients with impaired immunity should be treated longer with a course of oral acyclovir therapy 400 mg five times a day for 2 to 3 weeks. Alternatively famiciclovir 500 mg three times a day or valacyclovir 1 g three times a day can be used. Patients with severe odynophagia may require hospitalization for parenteral acyclovir therapy 5 mg/kg 3 times a day for 1 to 2 weeks [14]. Those who improve quickly can be switched to oral therapy. Patients who do not respond to therapy probably are infected with a virus strain resistant to acyclovir resulting from mutations within the thymidine kinase or the DNA polymerase gene of HSV. Viruses with thymidine kinase mutations are generally cross-resistant to other drugs in this class [20]. In that case treatment with foscarnet can be an option.

Cytomegalovirus-induced esophagitis

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is, like HSV, a member of the Herpesviridae family. Cytomegalovirus esophagitis is observed in patients who have undergone transplantation, those undergoing long-term dialysis, HIV-infected patients or those with long lasting steroid therapy [21, 22]. Until now no case was reported in immunocompetent hosts. The average time to development of CMV esophagitis after solid organ transplantation is about 6 months. Patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation may develop CMV disease at an average of 3 months or even much earlier. Studies show that even about 80% of the world’s population is CMV-positive [23].

Cytomegalovirus infection is a consequence of three possible mechanisms. About 60% represents primary infection which in patients with normal immunity causes few or no symptoms and CMV can persist in a latent form in most organs of the body. About 10–20% occurs in that group with a latent virus that becomes reactivated when the host’s immune system becomes compromised. The last 10–20% represents superinfection.

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis presents with fever, odynophagia, and nausea, and is occasionally accompanied by substernal burning pain. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy usually reveals large solitary ulcers or erosions seen in the distal esophagus. Ulcers seen in CMV infection tend to be linear or longitudinal and deep. A confirmatory biopsy demonstrates tissue destruction and the presence of intranuclear or intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies [24] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CMV-induced esophagitis

The treatment of CMV esophagitis involves induction therapy for 3 to 6 weeks, but optimal duration of therapy is not clear. Maintenance treatment is controversial. In general, intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg or foscarnet 90 mg/kg is recommended for induction therapy. Maintenance therapy with oral valganciclovir 900 mg twice a day seems to be an option in patients who have had a relapse. Reinduction therapy is required again before maintenance treatment [25].

References

- 1.Gąsiorowska A, Łapienis M, Schmidt J, et al. Evaluation of pH-impedance testing in diagnosis of patients with suspected extra-oesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Prz Gastroenterol. 2012;7:386–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JB, Freilich MM, Le ND. Risk factors for oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients who receive radiation therapy for malignant conditions of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:169–74. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90199-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iacopino AM, Wathen WF. Oral candidal infection and denture stomatitis: a comprehensive review. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:46–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangeorzan JA, Bradley SF, He X, et al. Epidemiology of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: colonization, infection, treatment, and emergence of fluconazole resistance. Am J Med. 1994;97:339–46. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanda N, Yasuba H, Takahashi T, et al. Prevalence of esophageal candidiasis among patients treated with inhaled fluticasone propionate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2146–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samonis G, Skordilis P, Maraki S, et al. Oropharyngeal candidiasis as a marker for esophageal candidiasis in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:283–6. doi: 10.1086/514653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonacini M, Young T, Laine L. The causes of esophageal symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus infection. A prospective study of 110 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1567–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–35. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips P, De Beule K, Frechette G, et al. A double-blind comparison of itraconazole oral solution and fluconazole capsules for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1368–73. doi: 10.1086/516342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koletar SL, Russell JA, Fass RJ, Plouffe JF. Comparison of oral fluconazole and clotrimazole troches as treatment for oral candidiasis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2267–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pons V, Greenspan D, Debruin M. Therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized, prospective multicenter study of oral fluconazole versus clotrimazole troches. The Multicenter Study Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez JA, Skiest DJ, Nieto L, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating posaconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in subjects with HIV/AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1179–86. doi: 10.1086/501457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darouiche RO. Oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in immunocompromised patients: treatment issues. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:259–72. doi: 10.1086/516315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, et al. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pursley TJ, Blomquist IK, Abraham J, et al. Fluconazole-induced congenital anomalies in three infants. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:336–40. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canalejo Castrillero E, Garcia Duran F, Cabello N, Garcia Martinez J. Herpes esophagitis in healthy adults and adolescents: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89:204–10. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e949ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald GB, Sharma P, Hackman RC, et al. Esophageal infections in immunosuppressed patients after marrow transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosimann F, Cuenoud PF, Steinhauslin F, Wauters JP. Herpes simplex esophagitis after renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 1994;7:79–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00336466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBane RD, Gross JB., Jr Herpes esophagitis: clinical syndrome, endoscopic appearance, and diagnosis in 23 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:600–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frobert E, Ooka T, Cortay JC, et al. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase mutations associated with resistance to acyclovir: a site-directed mutagenesis study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1055–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1055-1059.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcox CM, Rodgers W, Lazenby A. Prospective comparison of brush cytology, viral culture, and histology for the diagnosis of ulcerative esophagitis in AIDS. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:564–7. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemonovich TL, Watkins RR. Update on cytomegalovirus infections of the gastrointestinal system in solid organ transplant recipients. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bate SL, Dollard SC, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States: the national health and nutrition examination surveys, 1988-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1439–47. doi: 10.1086/652438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terada T. A clinicopathologic study of esophageal 860 benign and malignant lesions in 910 cases of consecutive esophageal biopsies. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:191–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitley RJ, Jacobson MA, Friedberg DN, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of cytomegalovirus diseases in patients with AIDS in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of an international panel. International AIDS Society-USA. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:957–69. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.9.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]