Fistula formation is a complication of diverticulitis in 4% to 20% of cases.1,2 The left or sigmoid colon is the most commonly involved segment. The most common presenting symptom is pneumaturia and dysuria, followed by fecaluria, abdominal pain and, rarely, hematuria.3–6 Some colovesical fistulas (CVFs) are asymptomatic.4–6 CVF is more common in males and in females with a history of hysterectomy.5,6 The diagnosis is usually made clinically but can be confirmed by cystoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or virtual colonoscopy.3,4,7 The usual management for symptomatic patients is colon resection, and there is still controversy in the approach to asymptomatic patients.4,6

Left colectomy for CVF secondary to diverticular disease can be very challenging owing to the presence of acute and chronic inflammation, which makes the tissues harder and more prone to bleeding. It is also more difficult to visualize and find proper anatomic planes and to identify vital structures. Conversion rates of laparoscopic sigmoidectomy complicated with diverticulitis are double that for cancer and as high as 30%.2,8–11 In general, a colectomy for diverticulitis is considered a more difficult operation than a colectomy for cancer, whether or not a laparoscopic or open approach is chosen.2,8 Some authors have proposed laparoscopic surgery as the gold standard approach for diverticular disease2 and CVF management.7,11 The safety of robotic surgery for colorectal diseases has been previously addressed in other studies.12–18 The purpose of our study is to review and compare our experience with laparoscopic left colectomy and robotic left colectomy for diverticular disease complicated with CVF. The primary end point was conversion.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of a prospective database. Robotic colorectal surgery was introduced into our practice in June 2009. A total of 251 robotic colectomies were performed from June 2009 to April 2013 in our practice. Of the 251 robotic colectomies, 112 were left colectomies and 20 of them were for CVF secondary to diverticular disease. We compared these 20 consecutive patients, who underwent robotic left colectomy for diverticular disease complicated with CVF, with 55 consecutive comparable cases performed laparoscopically from January 2001 to May 2009. All cases, laparoscopic and robotic, were performed by the same board-certified colorectal surgeons. Our standard practice for over 20 years has been to perform elective laparoscopic colectomy for diverticular disease with associated CVF.

All patients were 18 years or older and did not have any contraindication for major elective surgery. Only benign CVFs secondary to diverticular disease were included; malignant and emergent cases were excluded. Variables studied were age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA). Total operative room time (TORT) was defined as “wheels-in” to “wheels-out” and operative time (OT) was defined as the time from first incision to last skin closure. Intraoperative and postoperative complications and conversion rates were also recorded. Follow-up was done by the customary office visits. Informed consents were obtained from all patients. This protocol and database were Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved.

Conversion was defined as the use of an extraction site for any part of the dissection or CVF takedown. In other words, an extraction site was only used for specimen extraction. Conversion to laparoscopic surgery was defined as undocking the robot at any time prior to performing the anastomosis and performing any part of the dissection under laparoscopic guidance with the exception of the stapled anastomosis.

Two independent statisticians provided the data analysis. Mann-Whitney U tests and Fisher's exact tests were used. The results are reported as mean, median, standard deviation, and range. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Complications are reported using the Clavien-Dindo classification.19

Laparoscopic left colectomy with CVF takedown

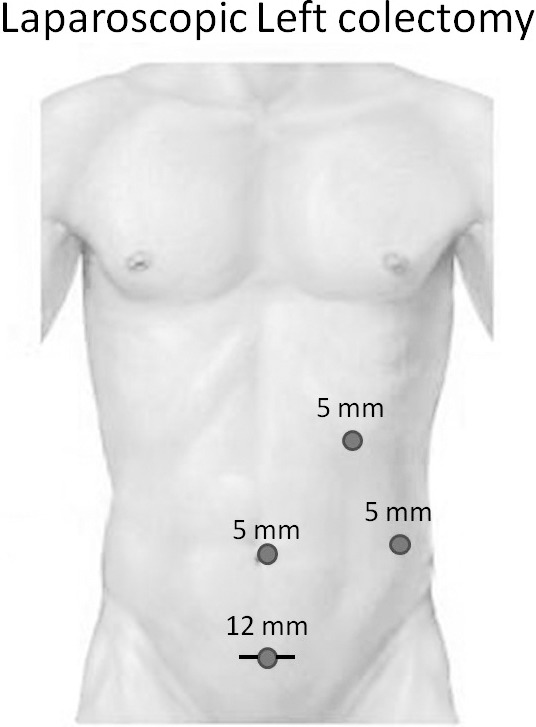

The patient is positioned supine with legs in Allen stirrups. Trocars (5 mm) are placed at umbilicus, left upper quadrant and left lateral, and a 12-mm port is placed suprapubic as shown (Fig. 1). First, the takedown of the CVF is performed. The sigmoid colon is detached from the bladder using an energy device and both blunt and sharp dissection. The colon mobilization is started lateral-to-medial by dissecting along the line of Toldt using a bowel grasper and the harmonic scalpel. The splenic flexure is mobilized if needed. The ureter is identified (sometimes with the aid of ureteral stents) and dissected out for its entire length. The sigmoid colon mesentery is elevated so as to identify the inferior mesenteric vessels. A window is created on both sides of the vessels near their origin. A linear endoscopic stapler, loaded with a vascular cartridge, is introduced through the 12-mm port and is fired across the mesenteric vessels near their origin. The rectosigmoid dissection is carried out circumferentially until the rectosigmoid junction is exposed; then it is transected using a linear stapler. The proximal limb of the colon is brought out through a suprapubic or left lower quadrant extraction site. The wound is protected with a wound retractor, and the anvil of the circular stapler is placed and secured with a purse string. The colon is returned back to the peritoneal cavity, and pneumoperitoneum is reestablished. The circular stapler is then inserted into the rectal stump, and the anastomosis is created under laparoscopic guidance. After correct orientation of the bowel is confirmed and a tension-free anastomosis assured, the stapler is closed, fired, and withdrawn. The pelvis is irrigated with saline, and an intraoperative flexible sigmoidoscopy is performed to test and confirm that the anastomosis is air- and watertight. The extraction site is closed in 2 layers, and the skin is closed in subcuticular fashion.

Fig. 1.

Laparoscopic port placement.

Robotic left colectomy with CVF takedown

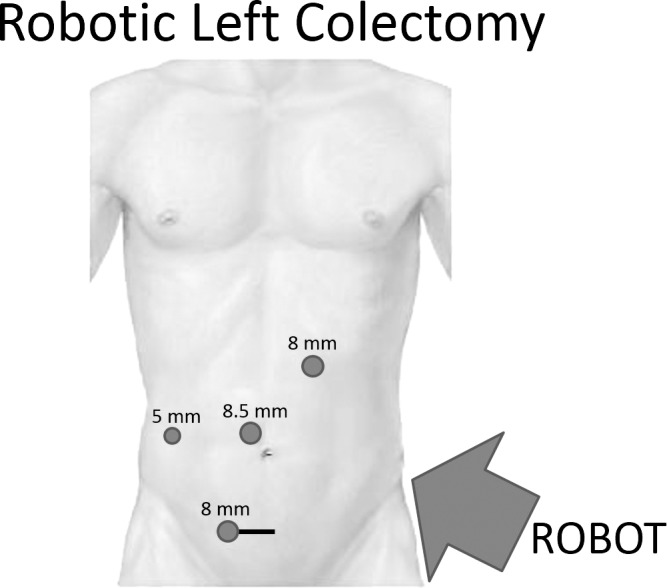

The patient is positioned supine with legs in Allen stirrups. A 5-mm incision is made in the left upper quadrant. A Veress needle is inserted for insufflation. After pneumoperitoneum is achieved, a 5-mm trocar and camera are introduced. A 3-arm hybrid technique is used; therefore, two 8-mm robotic ports and an 8.5-mm camera trocar are placed as shown (Fig. 2). A 12-mm assistant trocar is placed in the right upper/lateral quadrant. The robot is brought in over the patient's left hip for docking. First, the takedown of the CVF is performed. The sigmoid colon is detached from the bladder using hot shears and monopolar cautery. Next, the left colon is mobilized along the line of Toldt. The splenic flexure is mobilized as much as possible from this docking. Distally, the dissection is carried down to the peritoneal reflection. The ureter is identified and preserved. Medially, the mesentery is tented so as to identify the mesenteric vessels; a window is constructed on each side of the vessels, and then transected near their origin with a linear endoscopic stapler and vascular load. The remaining mesentery is taken down, with the harmonic scalpel if needed, to the level of the presacral space. More recently, we have been utilizing the EndoWrist One Vessel Sealer (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) for division of the mesenteric vessels at their origin and division of the mesentery. The dissection is carried out circumferentially until the rectosigmoid junction is exposed. The articulating linear stapler is introduced through the right lateral 12-mm port and fired by the assistant surgeon at this level. Typically, a suprapubic incision is created and protected with a wound protector for extraction of the specimen. However, a left lower quadrant incision or extension of the periumbilical camera port site can be used. The robot is undocked at this point. The intracorporeal anastomosis using a circular stapler and the rest of the operation are completed following the same laparoscopic technique as described above. If further splenic flexure mobilization is necessary, this is accomplished laparoscopically. In 2 cases, a robotic hysterectomy was also performed. In these cases, transvaginal specimen extraction was performed to avoid an abdominal wound.

Fig. 2.

Robotic port placement.

Results

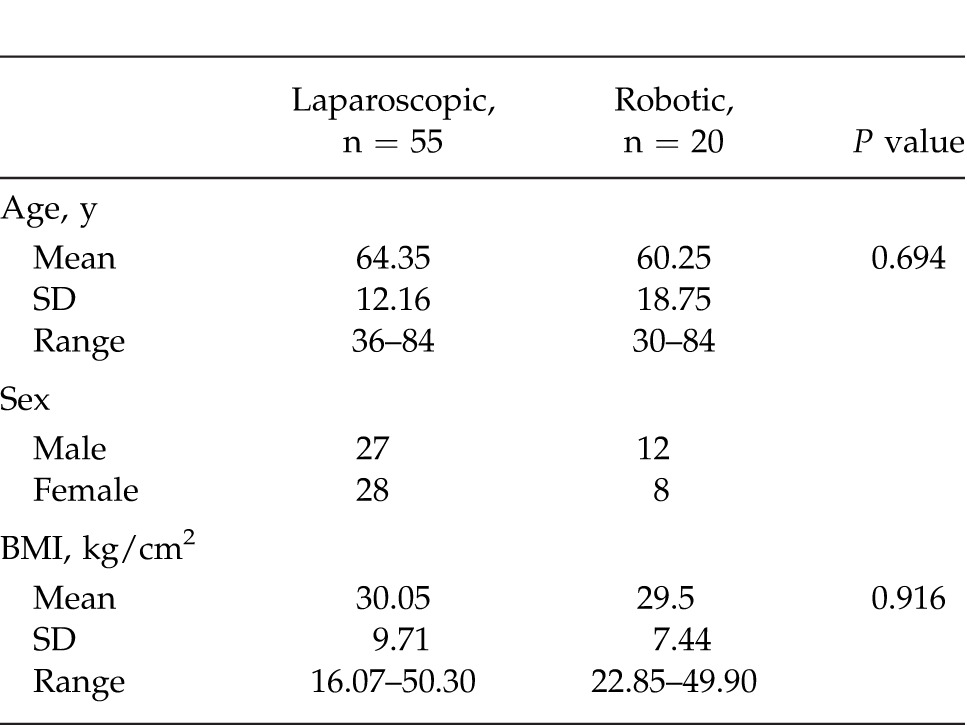

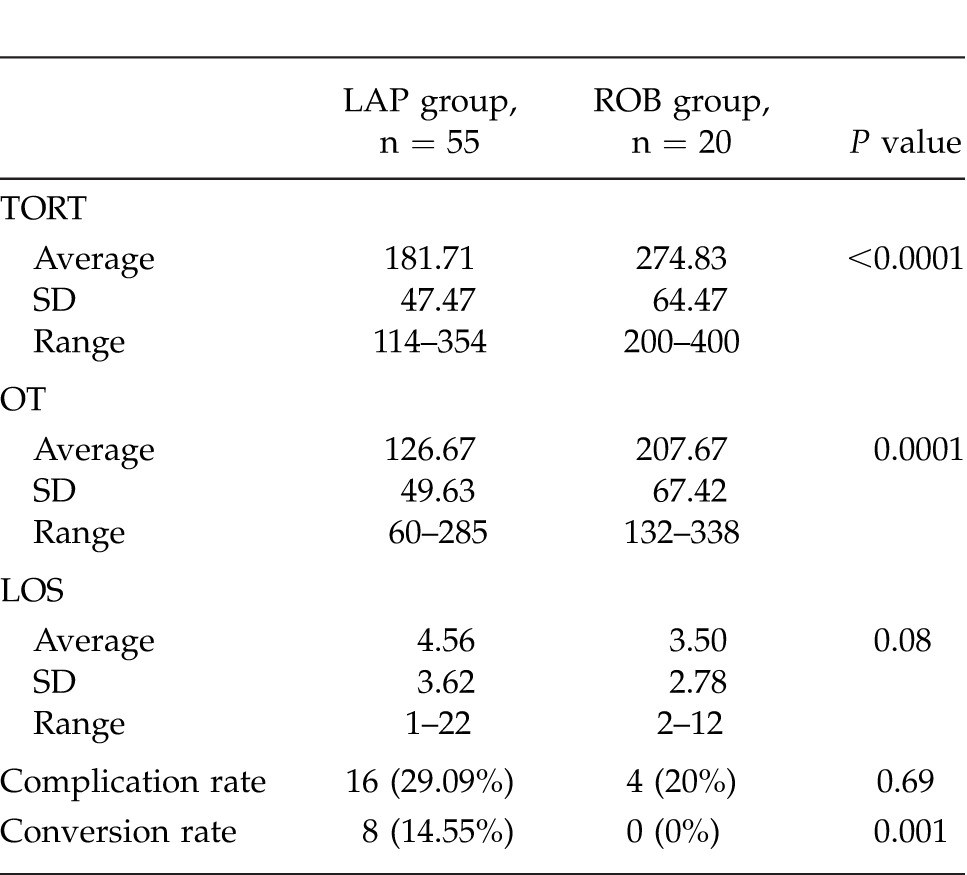

A total of 55 laparoscopic and 20 robotic left colectomies were studied. Both groups were similar (Table 1). The laparoscopic (LAP) group was composed of 27 males and 28 females; the robotic (ROB) group included 12 males and 8 females. Two patients in the ROB group also had associated colovaginal fistulas. Average age for the LAP group was 64.35 years (range, 36–84 years, SD ± 12.16); average age for the ROB group was 60.25 years (range, 30–84 years, SD ± 18.75) (P = 0.694). Average BMI for the LAP group was 30.05 (range, 16.07–50.30, SD ± 9.71) and for the ROB group was 29.50 (range, 22.85–49.90, SD ± 7.44) (P = 0.916). Average total operative room time (TORT) for the LAP group was 181.71 minutes (range, 114–354 minutes, SD ± 47.47) and for the ROB group was 274.83 minutes (range, 200–400 minutes, SD ± 67.42) (P = 0.0001). Average operative room time (OT) for the LAP cases was 126.67 minutes (range, 60–285 minutes, SD ± 46.93) and for the ROB cases was 207.67 minutes (range, 132–338 minutes, SD ± 67.42) (P = 0.0001). Complication rate for the LAP group was 29.09% and for the ROB group was 20.0% (P = 0.69). Average estimated blood loss (EBL) for the LAP group was 187.65 mL (range, 10–1000 mL, SD ± 182.26) and for the ROB group was 101.25 mL (range, 40–250 mL, SD ± 55.76) (P = 0.06). Eight patients in the LAP group were converted (8 of 55, 14.55%). No patients in the ROB group were converted to laparoscopic or open surgery (0 of 20, 0%) (P = 0.001). Average length of stay (LOS) for the LAP group was 4.56 days (range, 1–22 days, SD ± 3.62) and for the ROB group was 3.50 days (range, 2–12 days, SD ± 2.78) (P = 0.08). These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics

Table 2.

Summary of results

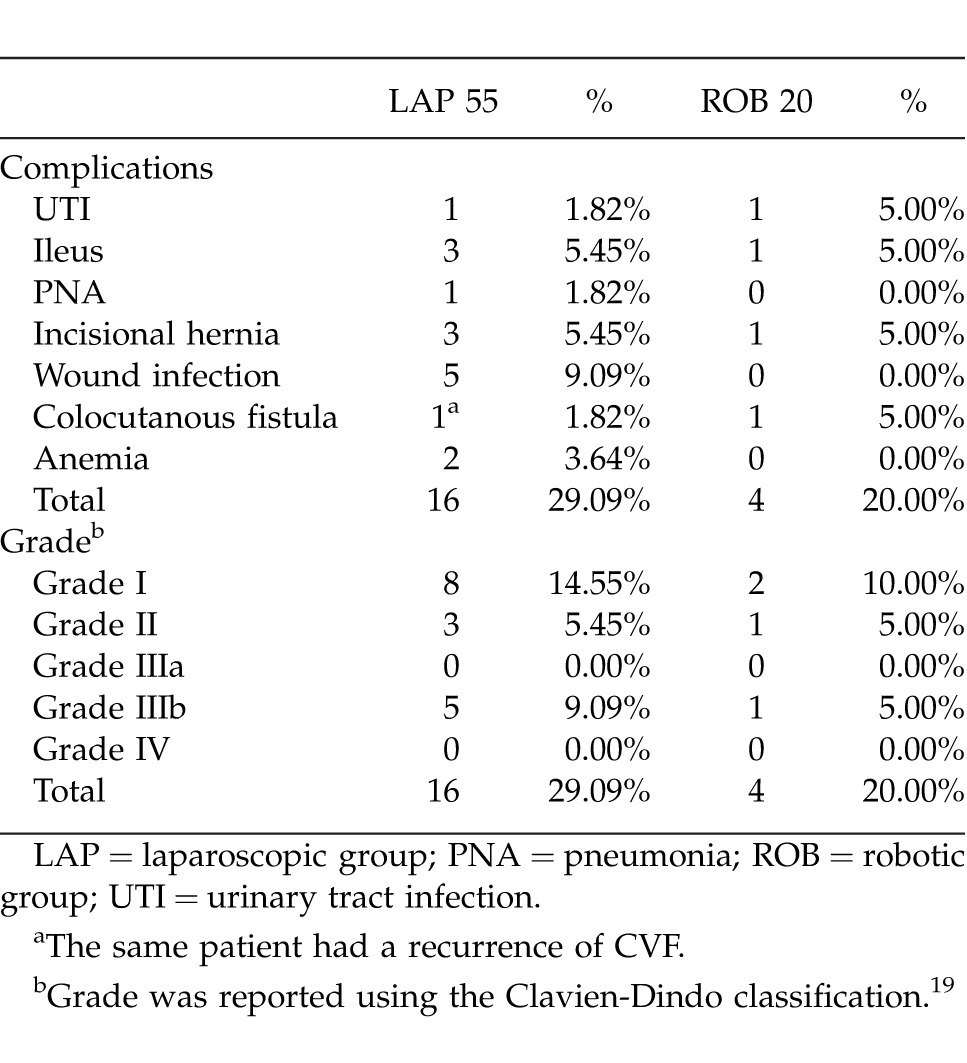

Complications

Two LAP cases required perioperative transfusions, while no patient in the ROB group required transfusion. Diversion was performed in 2 LAP and 1 ROB. There was 1 recurrence in the LAP group that also developed a colocutaneous fistula. There was 1 colocutaneous fistula in the ROB group. There was no 30-day mortality in either group. Mean follow-up was 266 days (range, 8–2500 days, SD ± 407).

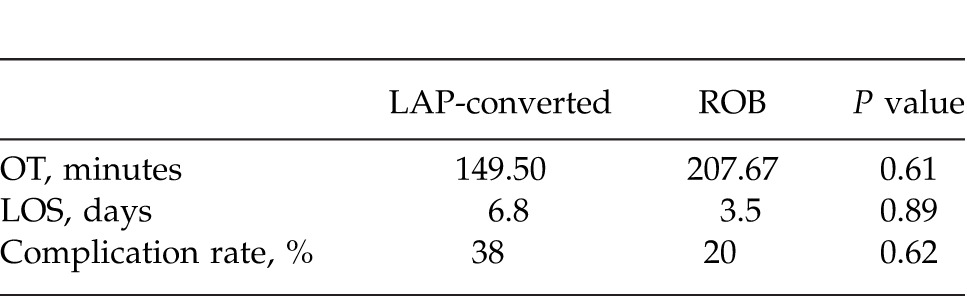

When the LAP-converted patients were compared with the ROB patients, the complication rate was higher for the converted LAP patients. The TORT and the OT times were still longer for the ROB cases (Table 3). Mean OT for LAP-converted cases was 149.5 minutes and 207.67 minutes for ROB cases (P = 0.61). Mean LOS for LAP-converted cases was 6.8 days and 3.5 days for ROB cases (P = 0.89). Complication rate for LAP-converted cases was 38% and for ROB cases was 20% (P = 0.62). Complications are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Lap-converted versus robotic

Table 4.

Complications

Discussion

Left colectomy for CVF is generally considered a technically demanding and difficult operation.2,7–9,11,20 Some authors have found that conversion rates are higher for laparoscopic colectomy for inflammatory diseases than for cancer. 2,8,21,22 Fifteen to 20 years ago, complicated cases like CVF were considered contraindications for laparoscopic colorectal surgery because of its intrinsic difficulty.1,10 At present, many authors consider these cases feasible and safe in expert hands and, furthermore, believe they offer patients the proven benefits of minimally invasive surgery.2,9–11,23 A PubMed search using the keywords “robotic,” “fistula,” and “repair” identified 1 report of successful CVF takedown with the DaVinci system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California). The authors recognized that their follow-up was short and that more study was necessary.18 To our knowledge, no published study has compared robotic with laparoscopic techniques in treating CVFs. The goal of this study was to review our experience with minimally invasive management of CVF and compare our early robotic experience with our laparoscopic experience.

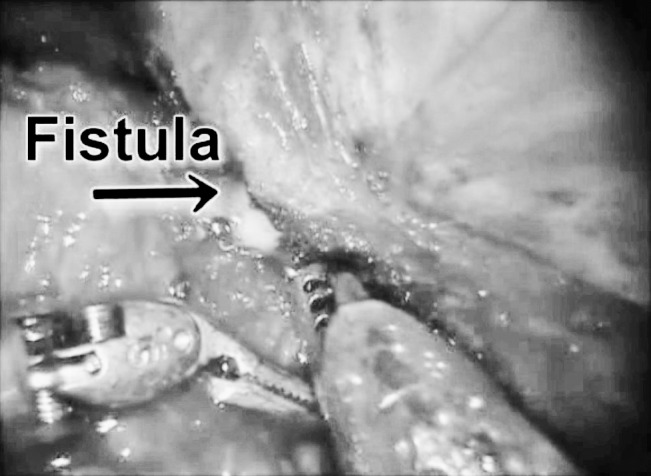

We have been performing laparoscopic surgery for all elective colectomies since 1991. Robotic techniques were introduced into our practice in June 2009. Robotic left colectomy has recently been shown to be safe and comparable to laparoscopic left colectomy by other authors.14,15,24,25 The purported advantages of the surgical robot have proven beneficial for urologic and gynecologic operations but are still being evaluated for colorectal surgery.18 We hypothesized that robotic surgery would facilitate left colectomy for CVF. Advantages attributed to DaVinci robotics include (1) surgeon-controlled, 3-dimensional (3-D), high-definition optics, (2) stable platform, (3) improved strength, and (4) articulating instruments. It was our subjective experience that the superior 3-D high-definition optics provided better visualization of dissection planes in severely inflamed tissues and difficult anatomic locations. The wristed instruments allowed better exposure and the ability to wedge between the sigmoid colon and the bladder (Fig. 3). Finally, the strength of the robot aided in the detachment of the 2 structures without the need of tactile assistance.

Fig. 3.

Fistula identification and takedown with robotic instruments.

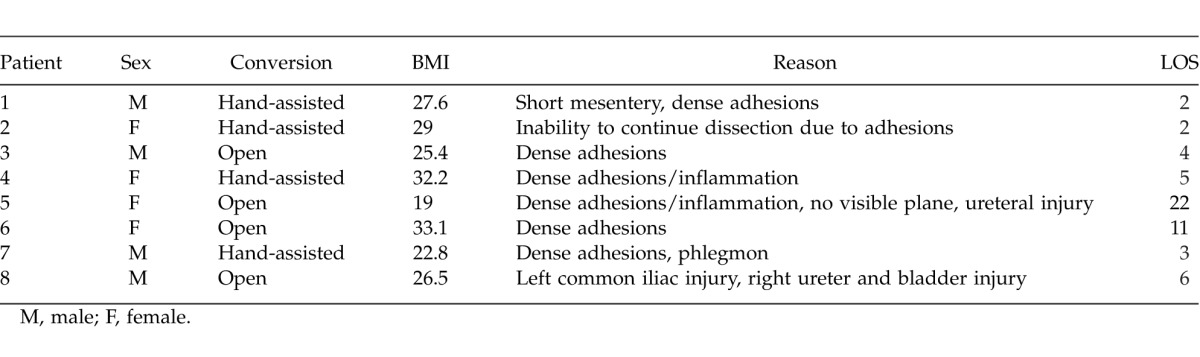

One commonly studied outcome in minimally invasive surgery is conversion. Laparoscopic colorectal procedures are converted in approximately 6% of the cases.14 Ranges from 0% to 46% have been reported.26 Conversion from a minimally invasive technique to an open procedure should not be considered a surgical complication; however, the clinical consequences of converting should not be ignored. In converted cases, authors have reported increased LOS, higher complication rates, slower return to bowel function, and increased need for opioid analgesics.2,9,20,22 Lord et al27 reported a significant prolongation in hospital stay for converted cases compared with purely laparoscopic procedures. However, in another study, Casillas et al21 studied conversions in laparoscopic colectomies and compared them with open colectomies. They found that neither the cost nor the perioperative complication rate increased in the event of a conversion compared with open procedures. In the specific case of laparoscopic colectomy, several studies concur in the findings that older age, high BMI, and surgeon's inexperience play a major role in the risk of converting cases of complicated diverticulitis.18,22,26,28,29 Yet, the Casillas' article affirms that the degree of inflammation found in CVFs is a more important risk factor for conversion than BMI.21 A correlation of our patients' BMI, sex, and LOS with conversion is detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Conversion and length of stay

Laparoscopic surgery for fistulized diverticulitis has been shown to be feasible and safe in experienced hands, but conversion is still a common occurrence.9 Bartus et al reported a 25% conversion rate for CVF cases.20 Conversion rates as high as 18.7% to 61% for left colectomies for CVF have been reported.8,9 In our study, the conversion rate in the laparoscopic cases was 14.55%. We used a strict definition for conversion. Conversions did result in longer incisions; usually an extension of the Pfannenstiel-type incision to varying lengths, and rarely to a midline. However, in the ROB group, after 20 consecutive cases, no cases required conversion (P = 0.001). Given the smaller number of cases in the ROB group, this statement has to be interpreted judiciously.

Our study groups were similar in demographics (sex, BMI, age). All patients were consecutive cases and not selected. Eight cases (14.55%) were converted in the LAP group (n = 55), and no cases (0%) were converted in the ROB group (n = 20). The advertised advantages of robotic surgery may be responsible for the lower conversion rate in the ROB group; however, it is difficult to measure the surgeons' contribution in this study. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Maeso et al reported a 2% robotic-to-open conversion rate and a 6% conversion to another form of surgery.14 Our results fall in line with this and other studies that show lower conversion rates attributed to robotic surgery.14,15

Another technically demanding operation is laparoscopic rectal resection, with conversion rates ranging from 1.2% to 34%. In the conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer: multicenter, randomized controlled trial (MRC CLASSIC), 32% conversion rate was shown (n = 796). In comparison, a recent meta-analysis, Antoniou et al15 showed a 0.4% conversion rate (n = 440) for robotic rectal resection in the published literature.30 Furthermore, analysis of the MRC CLASICC trial data also revealed higher morbidity and mortality associated with converted laparoscopic cases31; thus underlining the significance of conversions and suggesting a benefit to avoiding conversion. We performed an analysis of the laparoscopic-converted-to-open subgroup. When we compared the converted-LAP cases to the ROB group, the OT were not so dissimilar. Furthermore, LOS was shorter, and fewer complications occurred in the ROB group. However, the reduced complication rate did not reach statistical significance, so the use of robotic technology in reducing complication rates needs further evaluation (Table 4).

Two ureteral injuries occurred in the LAP group (Table 3). A major vascular injury also occurred in the LAP group. There was also 1 colocutaneous fistula with associated recurrence in the CVF, which was likely related to a subclinical postoperative anastomotic leak. This patient also had the Foley catheter mistakenly removed on the first postoperative day. No major intraoperative complications occurred in the ROB group. Although 1 leak occurred in the ROB group, this patient was diverted and drained at the time of the original operation. This patient was managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics. The patient had a low output colocutaneous fistula at the drain site that resolved spontaneously. These findings again suggest that robotic technology might be beneficial in preventing injuries while dissecting on very inflamed, hard tissues, but further study is needed. An independent risk-factor analysis was not performed. It is difficult to say whether the postoperative complication rate is affected more by converting or by the patients' general health and the pathology itself. Authors reported that morbidity correlated with the mere presence of fistula,11 and because both robotic and laparoscopy surgery are minimally invasive techniques, robotic assistance is unlikely to decrease postoperative complication rates. Our data are insufficient to comment on the differences in intraoperative and postoperative complications.

BMI did not seem to be an important factor for conversion. The BMI of the converted patients in the LAP group was within 1 SD of the mean BMI for the group. Also, the average BMI for both groups was similar, and no statistically significant difference was found (Table 1). This is consistent with the previously mentioned findings of Casillas et al that degree of inflammation is a more important risk factor for conversion than BMI.21 Furthermore, there was no correlation between sex, BMI, and conversion rate. Four men and 4 women were converted, supporting the theory that sex (and therefore pelvic size) is not as important a predictor for conversion as is the degree of inflammation present.11,26

Operative times for robotic surgery are generally longer than for laparoscopic cases. Laurent et al reported a mean OT of 172 minutes (range, 100–280 minutes) for left colectomy for diverticulitis, and a mean hospital stay of 5.7 days (range, 3–12 days).9 Our laparoscopic OTs compare favorably (mean, 107 minutes) with those reported in the literature. Furthermore, our ROB operative times, although longer than our LAP cases with a mean of 208 minutes, are still within the range of reported OTs for laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy in the literature. We could not find literature reports on OTs for robotic sigmoidectomy with CVF takedown for comparison. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Summary

To justify the use of robotic technology, with its increased cost and longer operative times, future studies will have to show an advantage over laparoscopy. Better visualization and articulated instruments may offer an advantage over laparoscopy in dissecting hard and inflamed tissues in the abdomen and pelvis, thereby resulting in a decrease in conversion rates. Our results suggest that robotic technology may decrease the conversion rate in difficult abdominal operations such as left colectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease. Although the literature shows that robotic surgery is not free of conversions,14 the advantages of robotic surgery might be of clinical significance in complicated, “high-risk-of-conversion” cases, such as fistulized diverticular disease.

Conclusion

Robotic techniques are safe and feasible for left colectomy and CVF takedown in the elective management of complicated diverticular disease. Both laparoscopic and robotic approaches have similar outcomes. Robotic surgery may decrease conversion rates compared with the laparoscopic approach. Robotics may also decrease blood loss, major complications, and LOS. More study is needed to evaluate the possible advantages of robotic surgery in the management of diverticular disease complicated by CVF.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was produced without any financial support from the medical device industry or other financial grants. Dr Lujan is an epicenter surgeon, a speaker, and receives honorarium from Intuitive Surgical. Dr Plasencia is a consultant for Ethicon-Endosurgery. Dr Lee is an Advanced Gastrointestinal Minimal Invasive Surgery Fellow supported by a grant from the Foundation of Surgical Fellowships.

References

- 1.Menenakos E, Hahnloser D, Nassiopoulos K, Chanson C, Sinclair V, Petropoulos P. Laparoscopic surgery for fistulas that complicate diverticular disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388(3):189–193. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bordeianou L, Rattner D. Is laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis the new gold standard? Gastro. 2010;Jun(4):2213–2216. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadir I, Ozin Y, Kiliç ZM, Oğuz D, Ulker A, Arda K. Colovesical fistula as a complication of colonic diverticulosis: diagnosis with virtual colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22(1):86–88. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charúa-Guindic L, Jiménez-Bobadilla B, Reveles-González A, Avendaño-Espinoza O, Charúa-Levy E. Incidencia, diagnóstico y tratamiento de fístula colovesical. Cir Cir. 2007;75(5):343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karamchandani MC, West CF. Vesicoenteric fistulas. Am J Surg. 1984;147(5):681–683. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solkar M, Forshaw M, Sankararajah D, Stewart M, Parker M. Colovesical fistula—is a surgical approach always justified? Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):467–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsivian A, Kyzer S, Shtricker A, Benjamin S, Sidi A. Laparoscopic treatment of colovesical fistulas: technique and review of the literature. Int J Urol. 2006;13(5):664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vargas HD, Ramirez RT, Hoffman GC, Hubbard GW, Gould RJ, Wohlgemuth SD, et al. Defining the role of laparoscopic-assisted sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(12):1726–1731. doi: 10.1007/BF02236858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent SR, Detroz B, Detry O, Degauque C, Honoré P, Meurisse M. Laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for fistulized diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(1):148–152. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joo JS, Agachan F, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic surgery for lower gastrointestinal fistulas. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(2):116–118. doi: 10.1007/s004649900310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwandner O, Farke S, Fischer F, Eckmann C, Schiedeck TH, Bruch HP. Laparoscopic colectomy for recurrent and complicated diverticulitis: a prospective study of 396 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389(2):97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Annibale A, Morpurgo E, Fiscon V, Trevisan P, Sovernigo G, Orsini C, et al. Robotic and laparoscopic surgery for colorectal diseases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(12):2162–2168. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0711-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Annibale A, Orsini C, Morpurgo E, Sovernigo G. Robotic surgery: considerations after 250 procedures. Chir Ital. 2006;58(1):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeso S, Reza M, Mayol JA, Blasco JA, Guerra M, Andradas E, et al. Efficacy of the Da Vinci Surgical system in abdominal surgery compared with that of laparoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):254–262. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e6239e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Koch OO, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery of the colon and rectum. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(1):1–11.: doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1867-y. 10.1007/s00464-011-1867-y Epub. doi: PubMed PMID: 21858568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baik SH. Robotic colorectal surgery. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49(6):891–896. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.6.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spinoglio G, Summa M, Priora F, Quarati R, Testa S. Robotic colorectal surgery: first 50 cases experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(11):1627–1632. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sotelo R, de Andrade R, Carmona O, Astigueta J, Velasquez A, Trujillo G, et al. Robotic repair of rectovesical fistula resulting from open radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;72(6):1344–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baik SH. Robotic Colorectal Surgery. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49(6):891–896. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.6.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartus CM, Lipof T, Sarwar S, Vignati PV, Johnson KH, Sardella WV, et al. Colovesical fistula: not a contraindication to elective laparoscopic colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;48(2):233–236. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casillas S, Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, Brady K, Fazio V. Does conversion of a laparoscopic colectomy adversely affect patient outcome? Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(10):1680–1685. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tekkis P, Senagore A, Delaney C. Conversion rates in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a predictive model with 1253 patients. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(1):47–54. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8904-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zapletal C, Woeste G, Bechstein WO, Wullstein C. Laparoscopic sigmoid resections for diverticulitis complicated by abscesses or fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(12):1515–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0359-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaney CP, Lynch AC, Senagore AJ, Fazio VW. Comparison of robotically performed and traditional laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(12):1633–1639. doi: 10.1007/BF02660768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmern A, Prasad L, DeSouza A, Marecik S, Park J, Abcarian H. Robotic colon and rectal surgery: a series of 131 cases. World J Surg. 2010;34(8):1954–1958. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Zhang G. Risk factors analysis and scoring system application of conversion to open surgery in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(5):322–326. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31822b0dcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lord SA, Larach SW, Ferrara A, Williamson PR, Lago CP, Lube MW. Laparoscopic resections for colorectal carcinoma: a three-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(2):148–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02068068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cima RR, Hassan I, Poola VP, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Larson DR, et al. Failure of institutionally derived predictive models of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal surgery to predict conversion outcomes in an independent data set of 998 laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):652–658. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d355f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarli L, Iusco DR, Regina G, Sansebastiano G, Ferro M, Veronesi L, et al. Predicting conversion to open surgery in laparoscopic left hemicolectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16(4):212–216. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, Nam BH, Choi HS, Kim DW, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):637–645. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3061–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]