Abstract

Oncolytic viruses have shown promise as gene delivery vehicles in the treatment of cancer; however, their efficacy may be inhibited by the induction of anti-viral antibody titers. Fowlpox virus is a nonreplicating and nononcolytic vector that has been associated with lesser humoral but greater cell-mediated immunity in animal tumor models. To test whether fowlpox virus gene therapy is safe and can elicit immune responses in patients with cancer, we conducted a randomized phase I clinical trial of two recombinant fowlpox viruses encoding human B7.1 or a triad of costimulatory molecules (B7.1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3; TRICOM). Twelve patients (10 with melanoma and 2 with colon adenocarcinoma) enrolled in the trial and were randomized to rF-B7.1 or rF-TRICOM administered in a dose escalation manner (∼3.7×107 or ∼3.7×108 plaque-forming units) by intralesional injection every 4 weeks. The therapy was well tolerated, with only four patients experiencing grade 1 fever or injection site pain, and there were no serious adverse events. All patients developed anti-viral antibody titers after vector delivery, and posttreatment anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody titers were detected in the two patients with colon cancer. All patients developed CD8+ T cell responses against fowlpox virus, but few responses against defined tumor-associated antigens were observed. This is the first clinical trial of direct (intratumoral) gene therapy with a nononcolytic fowlpox virus. Treatment was well tolerated in patients with metastatic cancer; all subjects exhibited anti-viral antibody responses, but limited tumor-specific T cell responses were detected. Nononcolytic fowlpox viruses are safe and induce limited T cell responses in patients with cancer. Further development may include prime–boost strategies using oncolytic viruses for initial priming.

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses have demonstrated significant promise in the treatment of cancer through preclinical animal models and early-phase clinical trials (Goldufsky et al., 2013). These vectors selectively replicate in tumor cells, induce direct lytic destruction of tumor cells, and promote systemic antitumor immunity. Vaccinia virus is an oncolytic virus that has been widely evaluated as an oncolytic vector and gene therapy agent and has several advantages (Tartaglia et al. 1990). These include the ability of the virus to selectively infect and replicate in tumor cells, the ability to reliably encode a large sequence of eukaryotic DNA in the virus, and an established safety profile in human subjects (Kim-Schulze and Kaufman, 2009). The use of vaccinia virus, however, is complicated by the emergence of neutralizing anti-vaccinia virus antibody titers and inability to use the virus in booster injections (Parato et al., 2005; Moritz et al., 2013). Fowlpox virus is an avian poxvirus that causes disease in birds but is nonpathogenic in mammals. In preclinical animal models fowlpox virus was shown to boost immune responses against foreign transgenes encoded by the viruses and to induce a strong T cell immune response, presumably because fowlpox virus does not replicate and thus does not induce neutralizing antibody titers in mammalian species (Gulley et al., 2008; Grupp et al., 2013b). Recombinant fowlpox viruses have been used in patients with cancer to induce immune responses against a variety of antigens in prime–boost strategies that have used vaccinia virus for initial priming followed by fowlpox virus for boosting (Hodge et al., 2003; Kaufman, et al., 2004; Kluth et al., 2013; Tsourlakis et al., 2013). However, fowlpox virus has not been tested as an intralesional gene therapy delivery vector in humans.

An advantage of using viruses and gene therapy vectors has been the use of such viruses to deliver T cell costimulatory molecules into the tumor microenvironment in order to directly kill tumor cells and to help promote tumor-specific immune responses. T cell activation depends on recognition of cognate antigen expressed as a processed peptide bound to MHC class I and II molecules by the T cell receptor of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively. To optimally activate the T cell a second, or costimulatory, signal is also required as exemplified by the CD80 (B7.1) costimulatory molecule on antigen-presenting cells that binds to CD28 on T cells and promotes T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and inhibition of T cell apoptosis (Grupp et al., 2013a). Several other immune-related molecules can serve as T cell costimulators, such as the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3 (LFA-3; CD58). Previous work has demonstrated that viral vectors encoding B7.1 can induce more potent T cell responses against tumor antigens compared with non-B7.1-expressing vectors, and the coexpression of a triad of costimulatory molecules, including B7.1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 (referred to as TRICOM) has been shown to be more potent than B7.1 alone (Schlom and Hodge, 1999).

We have previously shown that recombinant vaccinia viruses encoding B7.1 (rV-B7.1) can be safely injected directly into tumor cells and induce therapeutic responses in a small subset of patients treated in a phase I clinical trial (Komenaka et al., 2005). We also reported a small phase I clinical trial using a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding TRICOM (rV-TRICOM) and found this virus to be well tolerated and to have a 30.7% objective clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma (Kaufman et al., 2006). In these studies, all patients had high titers of anti-vaccinia virus antibodies detected after treatment and this may have limited the therapeutic effectiveness of the agents. Thus, we developed recombinant fowlpox viruses encoding human B7.1 (rF-B7.1) and TRICOM (rF-TRICOM) for further study in patients with cancer. To assess the safety and immune responses elicited by rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM as gene therapy vectors in patients with cancer, we designed a randomized, dose escalation, phase I clinical trial and herein report the results of this study.

Materials and Methods

Patient characteristics and study design

The clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University (New York, NY) and the study design has been previously reported (Kaufman et al., 2003). Patients with metastatic disease were eligible contingent on the following: (1) age, 18 years or more; (2) histologically proven unresectable metastatic solid tumor with cutaneous, subcutaneous, or nodal lesions greater than or equal to 1 cm in size; (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1; (4) negative serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) in women of childbearing potential; (5) no available standard therapy in patients; (6) at least 4 weeks from completing surgery or prior chemotherapy and complete recovery from the same; (7) at least 2 weeks from completing prior radiation therapy without evidence of bone marrow toxicity and complete recovery from the therapy; (8) at least 8 weeks from prior immunotherapy and complete recovery from the therapy; (9) life expectancy greater than 3 months; (10) no active autoimmune disorders or active immunologically mediated diseases; (11) no illness requiring systemic corticosteroids; (12) no significant allergy or hypersensitivity to eggs; (13) no history of another malignancy in the preceding 5 years other than stage I cervical carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma; (14) ability to avoid contact with high-risk individuals (immunosuppressed individuals, pregnant women, and children less than 3 years of age) for a period or 7–10 days after immunization; (15) adequate organ function as defined by a white blood cell count greater than or equal to 3000/mm3, platelet count greater than or equal to 100,000/mm3, serum creatinine less than or equal to 2.0 mg/mm3, serum total bilirubin less than or equal to 1.5 mg/dl, serum transaminase and alkaline phosphatase less than two times the upper limit of normal limits, a less than 2-fold elevation of prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time in patients not receiving anticoagulation medications and no evidence of congestive heart failure, serious cardiac arrhythmias, recent prior myocardial infarction, clinical coronary artery disease, or cirrhosis.

Patients received three intralesional injections every 4 weeks and objective disease response was determined by appropriate radiographic imaging 4 weeks after completing the three injections, using standard Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (Therasse et al., 2000). Two different doses of the rF-B7.1 (3.74×107 and 3.74×108 plaque-forming units [PFU]) and rF-TRICOM (3.78×107 and 3.78×108 [PFU]) vaccines were used. Before each injection, a history was taken and a physical examination was performed, and blood was collected for a complete blood count, anti-nuclear antibody titer, serum electrolyte levels, and coagulation studies. Safety was evaluated on the basis of National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC), version 3. Two weeks after each vaccination, serum and peripheral blood cells were obtained for immunologic studies. Four weeks after the third injection, patients underwent imaging to assess disease status. Those patients without objective disease progression and who still met eligibility criteria were offered three additional monthly booster vaccinations according to the same schema. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Analysis of antibody titers

Patient sera were collected before and 2 weeks after each vaccination and stored at −20°C. ELISA 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of wild-type fowlpox virus lysate antigens or carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) antigen at a concentration of 20 μg/ml overnight at 4°C. After washing the plate with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the plate was blocked for 1 hr at room temperature with 5% milk solution. Appropriate dilutions of control and sample sera were made with the same milk solution and incubated for 2 hr at 37°C. For antibody detection, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-tagged goat anti-human IgG (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was added, followed by the HRP substrate (TMB microwell peroxidase system; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Absorbance (optical density) was measured with a plate reader at 450 nm. A positive postvaccination response was indicated by a 2-fold increase in titer compared with the preimmunization titer.

Immunoblotting assays were conducted in order to detect CEA antibody in the sera of patients with colon cancer. Highly purified human CEA antigen (Fitzgerald, Concord, MA) was solubilized with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer, and 1 μg of CEA protein was electrophoresed in 4–20% Tris–glycine gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The protein was transferred to an Immun-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), which was then incubated overnight at 4°C with colon cancer patient serum diluted 1:200. Membrane-bound CEA antibody was detected with HRP-tagged goat anti-human IgG antibody (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC).

Identification of HLA-A2-restricted fowlpox peptide

To determine whether recombinant fowlpox viruses induce virus-specific T cell responses, we screened the fowlpox proteome for CD8+ T cell epitopes using an HLA motif algorithm to predict potential epitopes corresponding to the HLA-A2 family (Parker et al., 1994; http://www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/). The NCBI reference sequence of fowlpox virus is NC_002188. Candidate peptides were selected on the basis of both predicted binding affinity for HLA-A*0201 and amino acid sequence conservancy among all unique fowlpox isolates for which amino acid sequences have been reported. The five highest scoring peptides were synthesized, without modification, by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) BMLF-1259–267 (GLCTLVAML) was used as an irrelevant, HLA-A*0201-restricted control peptide.

To confirm that the fowlpox peptide was recognized by human CD8+ T cells in vitro, CD8+ T cells were separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of HLA-A2 healthy donors, using MACS CD8 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). CD8+ T cell-depleted PBMCs (10×106 cells per well) were pulsed with each fowlpox peptide at 50 μg/ml for 1 hr at room temperature and for 1 hr at 37°C in 5% CO2, and then washed twice with RPMI. PBMCs were then irradiated, washed, and used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs). CD8+ T cells (0.5×106 cells per well) were cocultured with peptide-pulsed irradiated PBMCs (1×106 cells per well) for 10–12 days. On days 1, 4, and 7, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing recombinant human interleukin (IL)-2 (20 IU/ml) and IL-7 (50 IU/ml).

A lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) was used to measure the cytolytic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. In 96-well plates, fowlpox peptide-pulsed HLA-A2-expressing melanoma cells were incubated with generated fowlpox peptide-specific CD8+ effector T cells at various effector-to-target ratios for 4 hr. Plates were centrifuged and 100 μl of supernatant from each well was transferred to new 96-well plates. Tetrazolium salt [2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2H-tetrazolium chloride; INT]-containing solution was added to each well. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the change in color was measured at a wavelength of 500 nm.

Analysis of T cell responses

PBMCs from study subjects were isolated by Ficoll gradient (Ficoll-Paque; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis. An enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was used to evaluate antigen-specific T cell IFN-γ responses. Briefly, frozen PBMCs were thawed and mixed with a 10-μg/ml concentration of HLA-A2-restricted gp100 (ITDQVPFSV) or MART-1 (AAGIGILTV). The next day, recombinant human IL-2 (100 IU/ml) and recombinant human IL-7 (10 ng/ml) (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA) were added. After 7 days of in vitro stimulation, the PBMCs were washed and added to anti-human IFN-γ antibody-coated 96-well plates (Mabtech, Cincinnati, OH) at 2×105 cells per well. Cells were stimulated in appropriate wells with peptides against fowlpox (ILAPFNFKV), gp100, and MART-1 peptides and against fowlpox virus lysate. Here, CEA antigen was used as a negative control peptide as all HLA-A2+ patients had melanoma and not colon adenocarcinoma. To differentiate fowlpox virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses from CD4+ T cell responses against fowlpox virus lysate, HLA-ABC blocking antibody (Ebioscience) was added in wells stimulated with fowlpox virus lysate. After a 24-hr incubation in an incubator, the plate was washed with PBS. Avidin–alkaline phosphatase-conjugated detection antibody (GIBCO-BRL, 100 μl; Invitrogen) diluted 1:4000 was added, and the plate was incubated for 2 hr at room temperature. After washing five times with PBS, 100 μl of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyl phosphate p-toluidine salt with nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (BCIP/NBT) phosphatase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to each well and the reaction was stopped by washing with water. A CEF peptide pool (cytomegalovirus [CMV], EBV, and flu virus peptide mixture; Mabtech) was used as a positive control. Spot numbers were counted with a CTL ImmunoSpot analyzer (Cellular Technology, Shaker Heights, OH).

In separate experiments, T cell responses were also evaluated against fowlpox virus-infected cell lysates by ELISPOT assay, as described previously. Experiments using a murine monoclonal anti-HLA-ABC antibody that blocks HLA-A-, HLA-B-, and HLA-C-mediated peptide presentation determined the HLA-A2 restriction element of presenting fowlpox peptides from whole virus lysate. The blocking antibody or isotype controls were added to the culture at 20 μg/ml for 90 min in appropriate wells before adding fowlpox lysate.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means±standard deviation (SD) or range when appropriate. A Student t test was used to compare two groups. When comparing three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was applied. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes

Twelve patients with nonresectable metastatic cancer who had at least a 1-cm cutaneous, subcutaneous, or nodal lesion were enrolled in the trial. Baseline characteristics and the sites of primary, metastatic, and vaccine-injected lesions are listed in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 53 years (range, 45–82). All patients had received and failed at least one prior therapy, including surgery (n=11), chemotherapy (n=4), IL-2 (n=4), and/or IFN-α (n=4). The primary tumor was melanoma in 10 patients and colon adenocarcinoma in 2 patients. Only grade 1 injection site pain and fever were observed in 4 of the 12 study subjects (Table 2). There was no correlation between toxicity and virus dose. On the basis of RECIST response criteria (Therasse et al., 2000), no objective responses were observed although three patients had stable disease of their index lesions, including one patient with melanoma (patient 7) and both patients with colon adenocarcinoma (patients 1 and 5; see Table 3). Patients tolerated treatment with minimal toxicity and no objective clinical responses were observed.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Vaccine | Dose (PFU) | Pt. no. | Age/sex | Primary cancer/metastasisa | Histology | Prior therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rF-B7.1 | 3.74×107 | 2 | 55/F | Abdominal wall s.c. nodule/lymph nodes, pectoralis major | Melanoma | S |

| 5 | 45/M | Cervical lymph node/lymph nodes, thyroid | Adenocarcinoma | C, S | ||

| 6 | 64/F | Inguinal lymph node/lymph nodes, liver | Melanoma | IL-2, IFN-γ | ||

| 3.74×108 | 9 | 76/M | Inguinal lymph node/lymph nodes | Melanoma | S | |

| 10 | 49/M | Inguinal lymph node/lymph nodes, lung | Melanoma | S | ||

| 12 | 53/M | Cervical lymph node/lymph nodes | Melanoma | C, S, IL-2, IFN-γ | ||

| rF-TRICOM | 3.78×107 | 1 | 53/M | Supraclavicular lymph node/lymph nodes, lung | Adenocarcinoma | C, S |

| 3 | 82/F | Axillary lymph nodule/lymph nodes, lung | Melanoma | S | ||

| 4 | 49/M | Ankle s.c. nodule/lung | Melanoma | S | ||

| 3.78×108 | 7 | 59/M | Back s.c. nodule/liver | Melanoma | S | |

| 8 | 51/M | Submandibular lymph node/lymph nodes, lung | Melanoma | S, IL-2, IFN-γ | ||

| 11 | 57/M | Frank s.c. nodule/mesentery | Melanoma | C, S, IL-2, IFN-γ |

C, chemotherapy; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-2, interleukin-2; PFU, plaque-forming units; Pt. no., patient number; s.c., subcutaneous; S, surgery.

Names of index lesions used for vaccine administration area are underlined.

Table 2.

Incidence of Adverse Events

| Vaccine | Dose (PFU) | Toxicity | Incidence | Max. grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rF-B7.1 | 3.74×107 | None | 0 | 0 |

| 3.74×108 | Pain | 1 | 1 | |

| Fever | 1 | 1 | ||

| rF-TRICOM | 3.78×107 | Fever | 1 | 1 |

| 3.78×108 | Fever | 1 | 1 | |

| Pain | 1 | 1 |

Max. grade, maximal grade; PFU, plaque-forming units.

Table 3.

Clinical Responses of Patients Treated with Intralesional rV-B.7.1 or rF-TRICOM Vaccine

| Response | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Dose (PFU) | Pt. no. | No. vaccinations | Tumor type | Target lesion | Nontarget lesion | Best overall response |

| rF-B7.1 | 3.74×107 | 2 | 1 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD |

| 5 | 3 | Colon adenocarcinoma | SD | PD | PD | ||

| 6 | 3 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| 3.74×108 | 9 | 2 | Melanoma | PD | Nonevaluable | PD | |

| 10 | 2 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| 12 | 2 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| rF-TRICOM | 3.78×107 | 1 | 3 | Colon adenocarcinoma | SD | PD | PD |

| 3 | 1 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| 4 | 3 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| 3.78×108 | 7 | 3 | Melanoma | SD | PD | PD | |

| 8 | 1 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

| 11 | 3 | Melanoma | PD | PD | PD | ||

No., number; PD, progressive disease; PFU, plaque-forming units; Pt. no., patient number; SD, stable disease.

Antibody responses

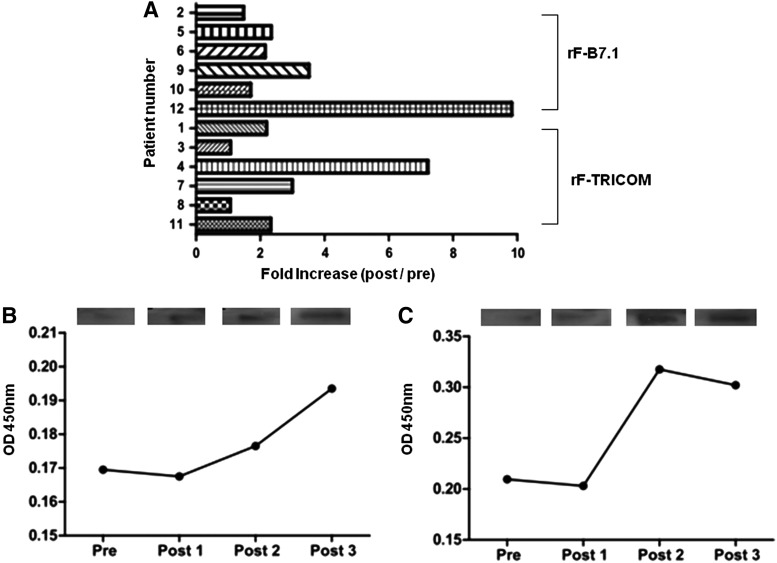

Pre- and postvaccination anti-fowlpox virus antibody titers were measured by standard ELISA. After rF-B7.1 or rF-TRICOM administration, all patients exhibited an increase in postvaccination fowlpox-specific antibody titers (Fig. 1A). There was no significant difference in anti-fowlpox virus antibody response between patients vaccinated with rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM (mean fold increase, 2.77±1.60 and 1.84±1.10, respectively). Differential dosing of the vaccines did not significantly alter anti-fowlpox virus antibody response (mean fold increase: low- and high-dose rF-B7.1, 2.14±0.89 and 3.40±2.09, respectively; low- and high-dose rF-TRICOM, 2.16±1.57 and 1.52±0.46, respectively). An increase in anti-CEA antibody response was detected in both patients with colon cancer, as illustrated by both ELISA and immunoblot assay (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG. 1.

Antibody responses to rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM vaccines. (A) Patient sera before (pre) and after (post) treatment were tested for fowlpox virus antibody by standard ELISA, and resulting antibody titers are shown (n=12 patients). (B and C) ELISA (graph) and immunoblotting results (rectangles at top) from the sera of two patients with colon cancer (patients 1 and 5, respectively) tested for anti-CEA antibody before (pre) and after one (Post 1), two (Post 2), or three (Post 3) rF treatments.

T cell responses

To identify fowlpox virus-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes, we generated novel nonamer peptides based on an HLA peptide-binding prediction program (http://www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/). The highest scoring HLA-A2-restricted fowlpox virus peptides were as follows: (1) hypothetical protein, WIWSPCCYV; (2) DNA polymerase, YLLFGIKCV; (3) DNA polymerase, ILAPFNFKV; (4) DNA polymerase, MLMETSFYI; and (5) ankyrin repeat, MLLDNGADV. PBMCs from each vaccinated patient were preloaded with one of the peptides and cocultured with each patient's CD8+ T cells, which were restimulated with the peptide with which they were primed and subjected to an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. CD8+ T cells primed with CEF peptide mixture or without peptide served as positive and negative controls, respectively.

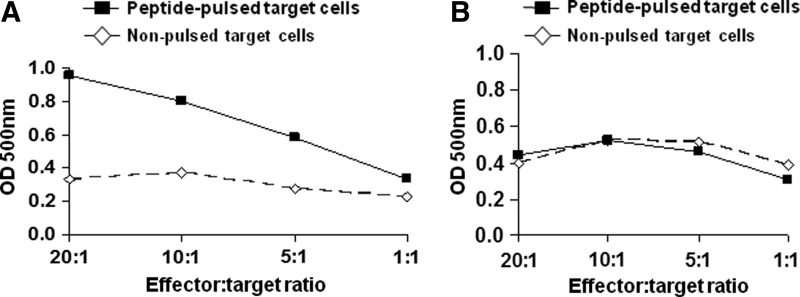

To identify cytotoxic fowlpox virus-specific T cell epitopes among the five predicted fowlpox virus peptides, PBMCs from normal donors were stimulated in vitro with each peptide for 7 days. The cells were then washed and subjected to a second round of in vitro stimulation, after which the functional cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells isolated from the PBMCs was determined by LDH assay. CTLs generated against DNA polymerase peptide (ILAPFNFKV) showed cytotoxicity against peptide-pulsed target cells, the degree of which was dependent on the ratio of effector to target cells (Fig. 2A). CD8+ T cells generated against the other four peptides did not show any significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of fowlpox virus-specific HLA-A2 epitopes. Recognition of fowlpox virus HLA-A2-restricted peptides by cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) lines was tested with peptide-pulsed HLA-A2 melanoma cells by LDH assay. (A) Absorbances at 500 nm in response to a fowlpox virus epitope recognized by patient CTLs (ILAPFNFKV), conducted at various ratios of effectors (patient CD8+ CTLs) to targets (patient PBMCs loaded with HLA-A2-restricted peptides). (B) Resultant absorbances at 500 nm in response to one of the fowlpox virus epitopes (MLMETSFYI) that did not result in CTL responses. These results shown are representative of three other peptides that did not result in peptide recognition.

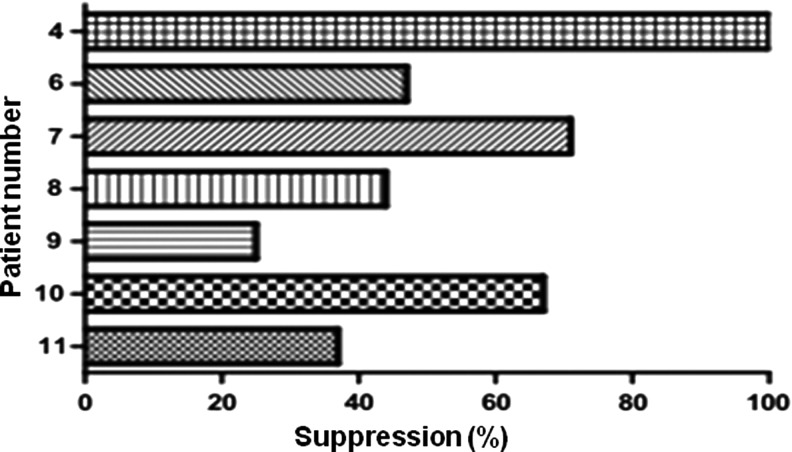

Tumor antigen-specific immune responses of patients before and after rF vaccination are shown in Table 4, as assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay of PBMCs stimulated with a single HLA-A2-restricted gp100 peptide and an HLA-A2-restricted MART-1 peptide. The postvaccination frequency of MART-1-specific T cells increased 3.9-fold in one of four HLA-A2-positive patients (25%), whereas gp100-specific T cells showed no difference or were not detected in these patients (Table 4). Recombinant fowlpox virus treatment induced fowlpox virus lysate-specific T cell responses in all eight evaluable (HLA-A2+) patients (Table 4), as assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT in which patient T cells were stimulated with virus lysate antigens or control CEA peptides. The addition of HLA-ABC blocking antibody inhibited IFN-γ secretion by T cells stimulated with fowlpox lysate by 25–100% (Table 4 and Fig. 3), suggesting that both rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM vaccines induce fowlpox virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. Patients 4 and 9 showed a significant increase in T cell response to the HLA-A2-restricted fowlpox virus peptide after vaccination (Table 4).

Table 4.

T Cell Responses to Fowlpox and Melanoma Antigens by IFN-γ ELISPOT Assay

| Vaccine | Pt. no. | HLA-A2 status | Time | Fowlpox peptide | gp100 peptide | MART-1 peptide | Fowlpox lysate+isotype control | Fowlpox lysate+HLA-ABC blockade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rF-B7.1 | 6 | 3, 11 | Pre | — | — | — | ND | ND |

| Post 1 | — | — | — | 19.5 | 14.5 | |||

| Post 2 | — | — | — | 17.5 | 5.5 | |||

| 9 | 2, 3 | Pre | 43.2 | ND | 9.2 | ND | ND | |

| Post 1 | 61.7 | ND | 36.0 | ND | ND | |||

| Post 2 | 35.7 | ND | 3.0 | 30.5 | 23.0 | |||

| 10 | 11, 32 | Pre | — | — | — | ND | ND | |

| Post 1 | — | — | — | 26.0 | 8.5 | |||

| 12 | 2, 24 | Pre | ND | ND | 4.5 | ND | ND | |

| Post 1 | ND | ND | ND | 69.5 | ND | |||

| Post 1 | ND | ND | ND | 24.5 | ND | |||

| rF-TRICOM | 4 | 2, 3 | Pre | ND | ND | ND | 3.5 | ND |

| Post 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Post 2 | ND | ND | ND | 35.5 | ND | |||

| Post 3 | 16.0 | ND | ND | 57.5 | ND | |||

| 7 | 24, 32 | Pre | — | — | — | ND | ND | |

| Post 1 | — | — | — | 34.0 | 10.0 | |||

| Post 2 | — | — | — | ND | ND | |||

| 8 | 3, 24 | Pre | — | — | — | ND | ND | |

| Post 1 | — | — | — | 31.5 | 17.5 | |||

| 11 | 2, 25 | Pre | 14.0 | 6.9 | 12.7 | 1.5 | 4.5 | |

| Post 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Post 2 | ND | ND | ND | 53.5 | 41.5 | |||

| Post 3 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 12.0 | 37.5 | 18.5 |

Pt. no., patient number; ND, not detected.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of IFN-γ secretion after HLA-ABC blockade. IFN-γ secretion was measured in postvaccination PBMCs from patients (n=7) treated with fowlpox virus lysate and either control IgG or HLA-ABC blocking antibody. Percent suppression by HLA-ABC blocking antibody was calculated as follows: difference in the number of prevaccination and postvaccination IFN-γ-secreting cells divided by the number of prevaccination IFN-γ-secreting cells.

Discussion

This clinical trial was designed to determine the safety and immune response of two recombinant fowlpox viruses encoding T cell costimulatory molecules, rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM, in patients with accessible metastatic cancer. This is the first clinical report of nononcolytic fowlpox viruses used as gene therapy vectors for direct local tumor injection. Adverse events related to rF vaccination were grade 1 injection site pain (n=1) and fever (n=3) (Table 2). These results are favorable compared with our previous recombinant vaccinia virus gene therapy trials, which documented grade 2 adverse events (injection site pain [n=11], vitiligo [n=1], and fatigue [n=6]) as well as grade 1 adverse events including fever, pain, rash, and nausea (Kaufman et al., 2005, 2006). We confirmed that intralesional injection of rF-B7.1 and rF-TRICOM is safe in patients with metastatic cancer. While our study was ongoing, another study was reported on the combination of subcutaneous and intratumoral vaccination using recombinant fowlpox virus encoding the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and a triad of costimulatory molecules termed TRICOM (B7.1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3) in men with locally recurrent or progressive prostate cancer (Gulley et al., 2013). This study showed limited grade 2 events and one grade 3 toxicity (a transient fever). Thus, fowlpox virus gene therapy has an acceptable safety profile in patients with cancer.

We also observed evidence of immune responses in patients treated with rF gene therapy. All patients (n=12) developed anti-fowlpox virus antibody titers after rF treatment (Fig. 1A). This was perhaps not surprising as previous studies of recombinant fowlpox viruses demonstrated the induction of potent virus-specific antibody titers (Radaelli et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate the induction of anti-viral antibody titers after local delivery into an established tumor site. We cannot determine whether this impacted the T cell or clinical responses in this small clinical trial, but the results do suggest that intratumoral gene therapy with fowlpox virus can induce a humoral immune response against the virus. We also observed CEA-specific antibodies in two patients with colorectal cancer who were treated with fowlpox viruses, suggesting that induction of antigen-specific antibody responses might be possible as well.

In this study, we identified a new HLA-A2-restricted fowlpox virus epitope that could be recognized by human CD8+ T cells (ILAPFNFKV). The immunogenicity of the epitope was confirmed with an LDH cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 2) and IFN-γ ELISPOT assay (Table 4). This peptide can be useful for future immune monitoring in clinical trials using fowlpox viruses as vectors. We also found that we could detect fowlpox-specific T cell responses using a fowlpox lysate in an interferon-γ ELISPOT assay. This was particularly useful for non-HLA-A2-expressing subjects and allowed us to confirm effective “vaccination” with the virus after treatment. In contrast, evidence of tumor antigen-specific T cell responses was less compelling with limited T cell responses against MART-1 seen in some patients with melanoma. The reason for the limited T cell response is not clear, but it may be that response assays were conducted 1 month after vaccination, and this may not have been sufficient time for optimal immune induction. Further, it may be that the nononcolytic nature of fowlpox virus induces less tumor cell lysis and limited release of soluble antigen. Another possible explanation for the lack of T cell response is the fact that the viruses do not encode tumor-associated antigens, so there may be less antigen presentation occurring after intralesional delivery of the virus into tumor cells. In addition, nononcolytic viruses may not promote a robust proinflammatory milieu in the tumor microenvironment as compared with oncolytic, replicating viruses. Because poxviruses inhibit host cell transcription and translation while promoting viral transcription, it may be important to encode potential tumor rejection antigens in nonreplicating vectors, such as fowlpox virus. Further studies might include an intralesional prime–boost approach in which vaccinia virus is used for priming T cell responses and fowlpox viruses encoding tumor antigens and T cell costimulatory molecules are used for boosting responses or forming long-lived memory responses (Stumm et al., 2013; Marshall et al. 2000). Alternating the route of administration may also be a strategy for improving immune responses and therapeutic activity of fowlpox viruses. For example, Gulley and colleagues demonstrated peripheral T cell responses against prostate-associated antigens in 4 of 9 patients tested, and 19 of 21 subjects exhibited a stable or improved serum PSA level after treatment with a combined subcutaneous and intratumor recombinant fowlpox virus, rF-PSA-TRICOM (Gulley et al., 2013).

Although we did not observe any objective responses in this trial, the study was not designed to evaluate therapeutic responses and it is possible that activity may be enhanced with increasing virus dose, altered administration schedule, or with the addition of other immune adjuvants such as cytokine or T cell checkpoint inhibitors. Advances in oncolytic virus therapy have demonstrated promising therapeutic results with modified herpesviruses encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in patients with melanoma (Senzer et al., 2009; Kaufman and Bines, 2010; Kaufman et al., 2010; Sivendran et al., 2010). These studies employed an every 2-week dosing regimen and demonstrated objective responses in patients despite the induction of anti-herpesvirus antibody titers (Senzer et al., 2009). Oncolytic vectors mediate antitumor activity through direct lytic effects and induction of systemic immunity, although the contribution of each component is not fully elucidated. An improved understanding of how oncolytic viruses mediate tumor regression might lead to better clinical trial designs incorporating combination vectors in a prime–boost strategy with or without additional immune adjuvants. Our data support the safety of nononcolytic fowlpox virus vectors for intratumoral gene therapy and suggest that this approach is associated with induction of anti-viral and tumor antigen-specific antibody responses, although T cell responses were limited. Further studies of combination and prime–boost regimens will likely be high priorities to more fully optimize the development of nononcolytic viruses for cancer treatment and human gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by federal funds: grant RO1 CA093696 from the National Cancer Institute (to H.L.K.). H.L.K. conceived and designed the clinical trial; H.L.K. and G.I. treated and evaluated patients; H.L.K., D.W.K., and S.K.S. processed samples and analyzed immune responses; H.L.K., D.W.K., S.K.S., M.C.J., and A.Z. analyzed and interpreted data; D.W.K., S.K.S., J.R.B., and A.Z. performed statistical analysis of the data; H.L.K., M.C.J., D.W.K., S.K.S., J.R.B., and A.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors have agreed to the content of this manuscript, including the data as presented.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Goldufsky J., Sivendran S., Harcharik S., et al. (2013). Oncolytic viruses for cancer treatment. Oncolytic Virother. 2, 31–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp K., Diebel F., Sirma H., et al. (2013a). SPINK1 expression is tightly linked to 6q15- and 5q21-deleted ERG-fusion negative prostate cancers but unrelated to PSA recurrence. Prostate 73, 1690–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp K., Hohne T.S., Prien K., et al. (2013b). Reduced CD147 expression is linked to ERG fusion-positive prostate cancers but lacks substantial impact on PSA recurrence in patients treated by radical prostatectomy. Exp. Mol. Pathol 95, 227– 234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley J.L., Arlen P.M., Tsang K.Y., et al. (2008). Pilot study of vaccination with recombinant CEA-MUC-1-TRICOM poxviral-based vaccines in patients with metastatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 3060–3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley J.L., Heery C.R., Madan R.A., et al. (2013). Phase I study of intraprostatic vaccine administration in men with locally recurrent or progressive prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 62, 1521–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge J.W., Poole D.J., Aarts W.M., et al. (2003). Modified vaccinia virus Ankara recombinants are as potent as vaccinia recombinants in diversified prime and boost vaccine regimens to elicit therapeutic antitumor responses. Cancer Res. 63, 7942–7949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., and Bines S.D. (2010). OPTIM trial: A phase III trial of an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF for unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Future Oncol. 6, 941–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., Cheung K., Haskall Z., et al. (2003). Clinical protocol: Intra-lesional rF-B7.1 versus rF-TRICOM vaccine in the treatment of metastatic cancer. Hum. Gene Ther. 14, 803–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., Wang W., Manola J., et al. (2004). Phase II randomized study of vaccine treatment of advanced prostate cancer (E7897): A trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 2122–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., Deraffele G., Mitcham J., et al. (2005). Targeting the local tumor microenvironment with vaccinia virus expressing B7.1 for the treatment of melanoma. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1903–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., Cohen S., Cheung K., et al. (2006). Local delivery of vaccinia virus expressing multiple costimulatory molecules for the treatment of established tumors. Hum. Gene Ther. 17, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H.L., Kim D.W., Deraffele G., et al. (2010). Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 17, 718–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Schulze S., and Kaufman H.L. (2009). Gene therapy for antitumor vaccination. Methods Mol. Biol. 542, 515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluth M., Hesse J., Heinl A., et al. (2013). Genomic deletion of MAP3K7 at 6q12-22 is associated with early PSA recurrence in prostate cancer and absence of TMPRSS2:ERG fusions. Mod. Pathol. 26, 975–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komenaka I.K., Deraffele G., Hurst-Wicker K.S., and Kaufman H.L. (2005). Management of metastatic melanoma to the breast with high-dose interleukin-2 and surgical resection. Breast J. 11, 158–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.L., Hoyer R.J., Toomey M.A., et al. (2000). Phase I study in advanced cancer patients of a diversified prime-and-boost vaccination protocol using recombinant vaccinia virus and recombinant nonreplicating avipox virus to elicit anti-carcinoembryonic antigen immune responses. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 3964–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz R., Ellinger J., Nuhn P., et al. (2013). DNA hypermethylation as a predictor of PSA recurrence in patients with low- and intermediate-grade prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 33, 5249–5254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parato K.A., Senger D., Forsyth P.A., and Bell J.C. (2005). Recent progress in the battle between oncolytic viruses and tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 5, 965–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K.C., Bednarek M.A., and Coligan J.E. (1994). Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J. Immunol. 152, 163–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli A., Bonduelle O., Beggio P., et al. (2007). Prime–boost immunization with DNA, recombinant fowlpox virus and VLP(SHIV) elicit both neutralizing antibodies and IFNγ-producing T cells against the HIV-envelope protein in mice that control env-bearing tumour cells. Vaccine 25, 2128–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlom J., and Hodge J.W. (1999). The diversity of T-cell costimulation in the induction of antitumor immunity. Immunol. Rev 170, 73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzer N.N., Kaufman H.L., Amatruda T., et al. (2009). Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 5763–5771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivendran S., Pan M., Kaufman H.L., and Saenger Y. (2010). Herpes simplex virus oncolytic vaccine therapy in melanoma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 10, 1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm L., Burkhardt L., Steurer S., et al. (2013). Strong expression of the neuronal transcription factor FOXP2 is linked to an increased risk of early PSA recurrence in ERG fusion-negative cancers. J. Clin. Pathol. 66, 563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia J., Pincus S., and Paoletti E. (1990). Poxvirus-based vectors as vaccine candidates. Crit Rev Immunol. 10, 13–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P., Arbuck S.G., Eisenhauer E.A., et al. ; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. (2000). New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsourlakis M.C., Walter E., Quaas A., et al. (2013). High Nr-CAM expression is associated with favorable phenotype and late PSA recurrence in prostate cancer treated by prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 16, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]