Abstract

Background

A significant proportion of the variability in carotid artery lumen diameter is attributable to genetic factors.

Methods

Carotid ultrasonography and genotyping were performed in the 3,300 American Indian participants in the Strong Heart Family Study (SHFS) to identify chromosomal regions harboring novel genes associated with inter-individual variation in carotid artery lumen diameter. Genome-wide linkage analysis was conducted using standard variance component linkage methods, implemented in SOLAR, based on multipoint identity-by-descent matrices.

Results

Genome-wide linkage analysis revealed a significant evidence for linkage for a locus for left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter in Arizona SHFS participants on chromosome 7 at 120 cM (lod=4.85 and 3.77, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=3.12 and 2.72, respectively, after adjustment for sex, age, height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus and current smoking). Other regions with suggestive evidence of linkage for left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter was found on chromosome 12 at 153 cM (lod=2.20 and 2.60, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.44 and 2.16, respectively, after full covariate adjustment) in Oklahoma SHFS participants; suggestive linkage for right carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter was found on chromosome 9 at 154 cM (lod=2.72 and 3.19, respectively after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.36 and 2.21, respectively, after full covariate adjustment) in Oklahoma SHFS participants.

Conclusion

We found significant evidence for loci influencing carotid artery lumen diameter on chromosome 7q and suggestive linkage on chromosomes 12q and 9q.

Keywords: genetics, carotid artery, ultrasonography, linkage analysis, variance components

Introduction

Studies have shown that carotid artery structure and function are not only influenced by cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors but also may represent phenotypic measures of vascular disease beyond those conferred by conventional CVD risk factors (1–4). Furthermore, recent studies have provided evidence of an association between carotid artery lumen diameter and risk of aortic aneurysm formation in population-based samples (5–6). In the Tromsø Study, investigators found that common carotid artery lumen diameter was independently associated with risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm in men (odds ratio, OR=1.9 [95% confidence interval, CI: 1.2–2.9]) and women (OR=4.1 [95% CI: 1.5–10.8]), suggesting an association between carotid artery dilatation and a general arterial dilating diathesis (5). Carotid artery lumen diameter is strongly influence by age, blood pressure (BP) and body size (7), and a significant proportion of the variability in carotid artery lumen diameter is attributable to genetic factors (8–10). Among American Indians participants in the Strong Heart Family Study (SHFS), we previously found that the heritability (h2) of carotid artery lumen diameter after adjusting for covariates is approximately 0.44 (with a standard error of ±0.07), suggesting that a substantial proportion of the inter-individual variability in carotid artery size is due to additive effects of genes (8). In this study, we conducted genome-wide linkage analysis of carotid artery lumen diameter to identify chromosomal regions harboring genetic variants associated with inter-individual variation in carotid artery lumen diameter in the American Indian participants in the SHFS.

Methods

Study Sample

The SHS is a population-based cohort survey of cardiovascular risk factors and prevalent and incident cardiovascular disease in American Indians. As previously described (11–12), the population included adult members of 13 tribes: 3 in North and South Dakota, 7 in southwestern Oklahoma and 3 in central Arizona. In 1998, the SHFS was initiated for genetic studies and participants aged 14 years and older were recruited without regard to disease status (13). Families were selected through sibships of two to eight siblings who had participated in the original epidemiological study. The parents, spouses, offspring, spouses of offspring, and grandchildren of the original participants were then recruited to construct extended, multigenerational pedigrees. Approval for the SHS and SHFS was granted by the institutional review boards of the Indian Health Service and the participating institutions as well as by the 13 American Indian tribes participating in these studies and all participants signed informed consent.

Carotid Ultrasound Measurements

Carotid ultrasound measurements were made using previously described methods (1, 7–8, 14–15). Briefly, the extracranial segments of the right and left carotid arteries were extensively scanned by using a high-frequency 2D ultrasound probe. Carotid artery structure was quantified from M-mode tracings of the distal common carotid artery obtained 1 to 2 cm from the carotid bulb; M-mode tracings were never obtained at the level of a discrete plaque. M-mode tracings were acquired by videotape with use of a frame-grabber and measurements were performed on digitized images with custom software (ARTSS, Cornell University). Minimum (end-diastolic) and maximum (end-systolic) carotid lumen diameters were obtained by continuous tracing of the lumen-intima interfaces of the near- and far-walls. In the families genotyped for the genome-wide linkage screen, left carotid artery lumen measurements were available for 1164 participants in Arizona, 1141 in North and South Dakota, and 1133 in Oklahoma; right carotid artery lumen measurements were available for 1159 participants in Arizona, 1130 participants in North and South Dakota and 1134 participants in Oklahoma. Carotid measurements were made by a highly experienced reader (MJR) with high intraobserver (r=0.98, SEE=0.04 mm) and interobserver (r=0.97, SEE=0.05 mm) reproducibility (16).

Marker Genotyping

Blood was drawn by venipuncture from fasting individuals. Buffy coats were isolated by centrifugation at the SHS regional clinics and then shipped on dry ice to the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research for DNA extraction using organic solvents. Each participant was genotyped using the ABI PRISM Linkage Mapping Set-MD10 Version 2.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), which is designed to amplify dinucleotide repeat markers selected from the Genethon human linkage map (17–18), covering the genome with markers spaced 10 cM apart on average. Nearly 400 markers were genotyped at satisfactory quality (381 in AZ, 380 in DK, and 393 in OK). The True Allele PCR Premix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for PCR amplification in Applied Biosystems 9700 thermocyclers, according to manufacturer’s specifications. Separate tubes were used for PCR amplification of each marker in each individual. The PCR products from different markers, from one individual, were subsequently pooled, together with a size standard, and loaded into an ABI PRISM 377 or 3100 Genetic Analyzer for laser-based automated genotyping using the Genescan and Genotyper software packages (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). CEPH DNA genotypes were used to confirm consistent allele naming between the gel-based and capillary-based instruments. Overall, 2076 individuals have been genotyped (707 in AZ, 698 in DK, 671 in OK).

Statistical methods

The stated pedigree relationships were verified with the software package PREST (19–20), based on the observed genotypes. The program SimWalk2 (21) was used to estimate error probabilities for the genotype at each marker in each individual (22), using the genotype data at all markers jointly, based on the genetic map by deCODE genetics (23) and marker allele frequencies estimated by maximum likelihood (24). This procedure can highlight genotypes that are inconsistent as well as those that are unlikely given the recombination fractions and allele frequencies used as input. We used an iterative process to eliminate genotypes likely to be erroneous until no more inconsistencies or likely erroneous genotypes remained.

The probabilities of identity-by-descent (IBD) allele sharing among pairs of related individuals were computed by the Monte Carlo Markov Chain approach implemented in software package Loki (25), in order to allow computation of IBD probabilities based on the genotypes at all linked markers jointly.

Heritability and genome-wide linkage analyses were conducted using the variance component approach implemented in software package SOLAR (26). The effects of factors likely to influence the phenotypes of interest (such as sex and age) were accounted for using a linear regression model, allowing for separate parameter values in the three different geographic cohorts. In order to ensure that the phenotypic distribution is appropriate for variance components analysis, the phenotypic residuals from the linear covariate adjustment were rank-normalized prior to analysis, i.e. the observations within each center were ranked and replaced with the expected values from a standard normal distribution for the given ranks. Joint analysis of all three centers was performed in two ways: In one model, the polygenic and quantitative trait locus (QTL) effects were constrained to be equal, which would be appropriate if one assumes that the three centers are genetically homogeneous and that shared common variants exist at QTLs to be mapped. In the other model, these parameters were allowed to vary by center, which would be appropriate if there are genetic differences between the tribes from the three regions, including the possibility that uncommon variants not shared between the different centers are responsible for some QTLs. While this latter model has three linkage parameters and associated degrees of freedom (and an assumed mixture distribution of a 0.125 point mass at zero, 0.375 chi(1), 0.375 chi(2), and 0.125 chi(3)), the likelihood ratios were converted into a regular logarithm of odds (LOD) score for convention and ease of comparison. In both models, all nuisance parameters (including allele frequencies and covariate regression coefficients) were allowed to vary between the three sites.

Based on the theory by Feingold et al. [27] which takes into account pedigree structures and the number of markers and genetic map, a LOD score of approximately 2.88 correspond to a genome-wide p-value of 0.05. This is essentially invariant among all three centers, since the same marker set was genotyped and the pedigree structures (regarding size, depth, width, average kinship size, and phenotype availability for pedigree members) are fairly similar.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of SHFS Participants by Field Center

The study sample consisted of 3,300 phenotyped individuals, with roughly equal number of participants from the three centers in Arizona, North/South Dakota, and Oklahoma. As seen in Table 1, SHFS participants were mostly female (~60%) and frequently overweight and diabetic, but with fairly well-controlled blood pressure. SHFS participants in North/South Dakota had slightly lower prevalent hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus but higher prevalence of current smoking compared to SHFS participants in Arizona and Oklahoma. An overview of the carotid arterial measurements is given in Table 2. In general, male SHFS participants had slightly but statistically significantly larger carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameters compared to female SHFS participants (all p<0.05). There were no differences in male or female carotid artery lumen diameter between centers.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Strong Heart Family Study Participants by Field Center

| Field Center | Sex (% female) | Mean Age (Years) | Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Diabetes1 (%) | Mean SBP (mm Hg) | Mean DBP (mm Hg) | Hypertension2 (%) | Hypertension Treatment (%) | Currently Smoking (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ | 62.3 | 37.2 | 35.4 | 33.3 | 121.0 | 76.6 | 34.2 | 22.5 | 22.6 |

| DK | 58.5 | 39.0 | 30.2 | 14.4 | 120.1 | 75.3 | 23.5 | 15.1 | 42.8 |

| OK | 58.5 | 43.6 | 31.1 | 20.5 | 126.7 | 76.8 | 37.3 | 22.9 | 33.1 |

| All | 59.9 | 39.9 | 32.3 | 22.8 | 122.6 | 76.2 | 31.7 | 20.2 | 33.8 |

: by American Diabetes Association (ADA) definition

: by US hypertension definition

Table 2.

Overview of Carotid Arterial Measurements (mean and range) by Field Center and Sex

| Field Center | Sex | Sample Size (range for different traits) | LeftDD (mm) | LeftSD (mm) | RightDD (mm) | RightSD (mm) | AvDD (mm) | AvSD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ | Both | 1,121 – 1,164 | 5.77 (3.07 – 10.90) | 6.54 (4.77 – 9.60) | 5.90 (4.20 – 9.70) | 6.67 (4.75 – 9.97) | 5.83 (4.37 – 9.30) | 6.60 (4.99 – 9.14) |

| Female | 699 – 724 | 5.54 (3.07 – 8.00) | 6.27 (4.77 – 8.39) | 5.69 (4.20 – 8.38) | 6.43 (4.75 – 9.30) | 5.61 (4.37 – 8.19) | 6.34 (4.99 – 8.85) | |

| Male | 422 – 441 | 6.15* (4.30 – 10.90) | 6.98* (4.80 – 9.60) | 6.26* (4.70 – 9.70)* | 7.09* (5.30 – 9.97) | 6.19* (4.89 – 9.30) | 7.02* (5.45 – 9.14) | |

|

| ||||||||

| DK | Both | 1,101 – 1,141 | 5.77 (4.27 – 9.10) | 6.55 (4.75 – 9.70) | 5.91 (4.00 – 9.60) | 6.66 (4.60 – 10.85) | 5.82 (4.19 – 9.30) | 6.59 (4.72 – 10.05) |

| Female | 644 – 671 | 5.57 (4.30 – 7.95) | 6.31 (4.75 – 8.40) | 5.73 (4.00 – 9.25) | 6.44 (4.60 – 9.20) | 5.64 (4.19 – 8.60) | 6.37 (4.72 – 8.27) | |

| Male | 457 – 470 | 6.04* (4.27 – 9.10) | 6.89* (5.15 – 9.70) | 6.16* (4.20 – 9.60) | 6.96* (4.60 – 10.85) | 6.09* (4.61 – 9.30) | 6.92* (5.61 – 10.05) | |

|

| ||||||||

| OK | Both | 1,092 – 1,134 | 5.72 (2.90 – 8.60) | 6.40 (3.00 – 9.50) | 5.77 (3.87 – 8.80) | 6.46 (4.30 – 9.57) | 5.74 (4.10 – 8.45) | 6.43 (4.50 – 9.34) |

| Female | 641 – 667 | 5.49 (2.90 – 8.10) | 6.12 (3.00 – 8.70) | 5.55 (3.87 – 8.80) | 6.21 (4.30 – 9.57) | 5.52 (4.10 – 8.45) | 6.16 (4.50 – 9.10) | |

| Male | 451 – 469 | 6.05* (4.30 – 8.60) | 6.81* (5.00 – 9.50) | 6.07* (4.00 – 8.45) | 6.82* (4.40 – 9.25) | 6.05* (4.25 – 8.00) | 6.81* (4.72 – 9.34) | |

|

| ||||||||

| All | Both | 3,314 – 3,438 | 5.75 (2.90 – 10.90) | 6.50 (3.00 – 9.70) | 5.86 (3.87 – 9.70) | 6.60 (4.30 – 10.85) | 5.80 (4.10 – 9.30) | 6.54 (4.50 – 10.05) |

| Female | 1,984 – 2,061 | 5.54 (2.90 – 8.10) | 6.23 (3.00 – 8.70) | 5.66 (3.87 – 9.25) | 6.36 (4.30 – 9.57) | 5.59 (4.10 – 8.60) | 6.29 (4.50 – 9.10) | |

| Male | 1,330 – 1,377 | 6.08* (4.27 – 10.90) | 6.89* (4.80 – 9.70) | 6.16* (4.00 – 9.70) | 6.95* (4.40 – 10.85) | 6.11* (4.25 – 9.30) | 6.91* (4.72 – 10.05) | |

Abbreviations: LeftDD: left diastolic diameter; RightDD: right diastolic diameter; AvDD: average diastolic diameter (average of left and right side); LeftSD: left systolic diameter; RightSD: right systolic diameter; AvSD: average systolic diameter (average of left and right side);

-p<0.05 compared to female SHS participants.

Heritability and Genetic Linkage of Carotid Artery Lumen Diameter in SHFS Participants

As seen in Table 3, carotid artery lumen diameters were highly heritable across field centers in both sex and age-adjusted (ranging from 0.28 to 0.56) and fully-adjusted models (ranging from 0.29 to 0.45), consistent with our previous report (8). The heritability estimates were consistently slightly higher in North/South Dakota than in the other two centers.

Table 3.

Heritability Estimates of Carotid Arterial Measurements (mean and range) by Field Center

| Trait | Field Center | No. of Pedigrees | Sex and Age-Adjusted Model1 | Fully-Adjusted Model2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No. of Individuals with Complete Phenotypic Data | Heritability3 | No. of Individuals with Complete Phenotypic Data | Heritability3 | |||

| LeftDD | AZ | 27 | 1,164 | 0.36 | 1,132 | 0.31 |

| DK | 22 | 1,141 | 0.46 | 1,126 | 0.35 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,133 | 0.36 | 1,128 | 0.37 | |

|

| ||||||

| LeftSD | AZ | 27 | 1,164 | 0.41 | 1,132 | 0.35 |

| DK | 22 | 1,141 | 0.46 | 1,126 | 0.33 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,133 | 0.35 | 1,128 | 0.36 | |

|

| ||||||

| RightDD | AZ | 26 | 1,159 | 0.33 | 1,128 | 0.30 |

| DK | 22 | 1,130 | 0.51 | 1,117 | 0.40 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,134 | 0.28 | 1,127 | 0.29 | |

|

| ||||||

| RightSD | AZ | 26 | 1,159 | 0.38 | 1,128 | 0.34 |

| DK | 22 | 1,130 | 0.49 | 1,117 | 0.38 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,134 | 0.30 | 1,127 | 0.32 | |

|

| ||||||

| AvDD | AZ | 26 | 1,121 | 0.41 | 1,092 | 0.38 |

| DK | 22 | 1,101 | 0.56 | 1,088 | 0.45 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,092 | 0.38 | 1,087 | 0.39 | |

|

| ||||||

| AvSD | AZ | 26 | 1,121 | 0.47 | 1,092 | 0.43 |

| DK | 22 | 1,101 | 0.55 | 1,088 | 0.43 | |

| OK | 11 | 1,092 | 0.37 | 1,087 | 0.39 | |

: Phenotypes were adjusted for sex, age, sex×age, age2, and sex×age2.

: Phenotypes were adjusted for sex, age, sex×age, age2, sex×age2, weight, height, SBP, DBP, DM status (ADA definition) and current smoking status.

: All heritability estimates are highly significant (p < E-8).

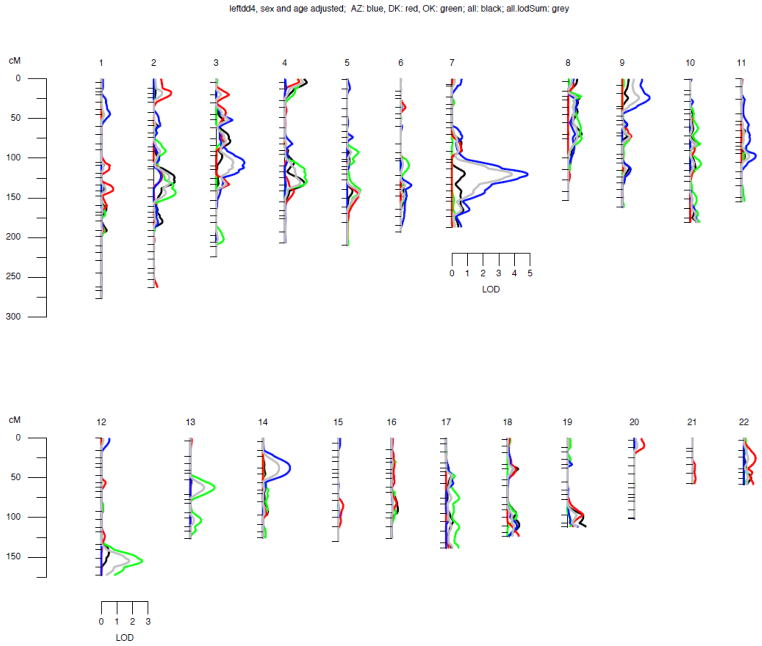

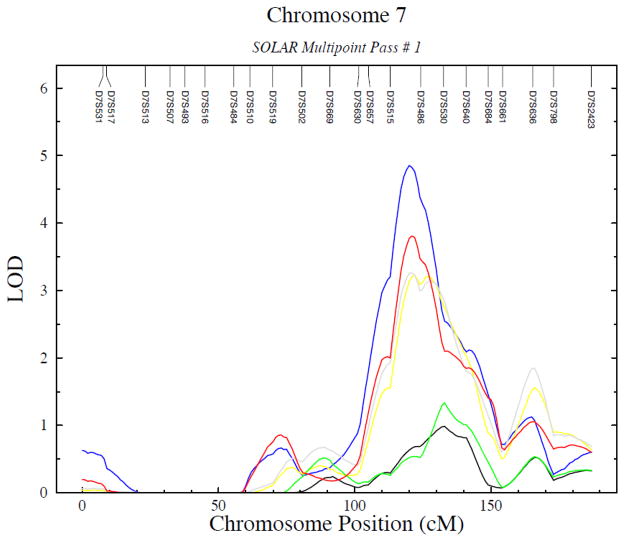

Genome-wide linkage scan results are summarized in Table 4. In this dataset, LOD scores of approximately 2.88 correspond to a genome-wide significance level of 0.05. A significant linkage peak (28) was obtained with left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter in Arizona SHFS participants on chromosome 7 at 120 cM (4.85 and 3.77 for the left diastolic and systolic diameter, respectively, using the sex and age-adjusted model and 3.12 and 2.72 for the left diastolic and systolic diameter, respectively, using the fully-adjusted model; Figures 1 and 2). In addition, another significant linkage peak was obtained in the Oklahoma sample for the right systolic diameter on chromosome 9 at 154 cM (lod=3.19), with nearly significant linkage evidence also for the right diastolic diameter at the same location (lod=2.72), after adjusting for age and sex; the lod scores were attenuated to 2.31 and 2.36, respectively, after full covariate adjustment. Suggestive evidence of linkage for left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter was also found in chromosome 12 at 153 cM (lod=2.20 and 2.60, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.44 and 2.16, respectively, after full covariate adjustment); suggestive linkage for left carotid artery systolic lumen diameter but not diastolic lumen diameter was found in chromosome 13 at 103 cM (lod=2.16, after full covariate adjustment) in Oklahoma SHFS participants. (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logarithm of Odds (lod) Score Peaks for Carotid Arterial Measurements by Field Center

| Field Center | Trait | lod at chr. 7 at 120 cM | lod at chr. 9 at 154 cM | Suggestive1 lod Scores Elsewhere in Genome (Chr., Location, lod) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Sex and Age- Adjusted Model2 | Fully- Adjusted Model3 | Sex and Age- Adjusted Model2 | Fully-Adjusted Model3 | Sex and Age-Adjusted Model1 | Fully-Adjusted Model2 | ||

| AZ | LeftDD | 4.85 | 3.12 | 0.00 | 0.04 | - | - |

| LeftSD | 3.77 | 2.72 | 0.00 | 0.00 | chr. 14, 35 cM, 2.28 | chr. 9, 3 cM, 2.06- | |

| RightDD | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.01 | - | - | |

| RightSD | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | chr. 15, 32 cM, 2.75 | - | |

| AvDD | 3.26 | 2.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| AvSD | 3.13 | 2.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

|

| |||||||

| DK | LeftDD | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | - | - |

| LeftSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| RightDD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | - | - | |

| RightSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | - | - | |

| AvDD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | - | chr. 1, 109 cM, 2.06 | |

| AvSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

|

| |||||||

| OK | LeftDD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | chr. 12, 153 cM, 2.20 | chr. 12, 153 cM, 2.44 |

| LeftSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | chr 12, 153 cM, 2.60 | chr. 12, 153 cM, 2.16 | |

| chr. 13, 103 cM, 2.16 | |||||||

| RightDD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.72 | 2.36 | - | - | |

| RightSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.19 | 2.31 | - | - | |

| AvDD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.96 | - | - | |

| AvSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.56 | - | chr. 13, 96 cM, 2.34 | |

|

| |||||||

| All4 | LeftDD | 0.82 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.07 | - | - |

| LeftSD | 0.46 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| RightDD | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.42 | 1.40 | - | - | |

| RightSD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.60 | - | - | |

| AvDD | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.72 | - | - | |

| AvSD | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.03 | - | - | |

|

| |||||||

| All, with inter-center hetero- geneity4 | LeftDD | 3.84 | 2.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - |

| LeftSD | 2.84 | 1.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| RightDD | 0.13 | 0.07 | 2.04 | 1.69 | - | - | |

| RightSD | 0.20 | 0.17 | 2.32 | 1.54 | chr. 15, 33 cM, 2.27 | - | |

| AvDD | 2.37 | 1.47 | 0.47 | 0.48 | - | - | |

| AvSD | 2.26 | 2.01 | 0.36 | 0.15 | - | - | |

: LOD score ≥1.96 (26)

: Phenotypes were adjusted for sex, age, sex×age, age2, and sex×age2.

: Phenotypes were adjusted for sex, age, sex×age, age2, sex×age2, weight, height, SBP, DBP, DM status (ADA definition), and current smoking status.

: See text for details on the differences between both types of analysis on total sample.

Figure 1. Genome-wide linkage results for LeftDD in different field centers.

Chromosomes are oriented vertically and identified by the number on top. Hatch marks indicate the positions of genotyped marker loci. The scale of the genetic map is given on the left. The lod score scale is indicated below the chromosomes giving the highest genome-wide LOD scores.

Blue: AZ; red: OK; green: DK; black: all; grey: all, allowing for inter-center heterogeneity (see text for details on the two different analyses on the entire sample).

Figure 2.

Linkage results on different carotid artery diameter measures for chromosome 7 in AZ. The positions of genotyped marker loci are indicated on top.

Blue: LeftDD, red: LeftSD, green: RightDD; black: RightSD;, grey: AvDD; yellow: AvSD

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that a significant proportion of the variability in carotid artery lumen diameter is attributable to genetic factors (8–10). We have identified, for the first time, several novel chromosomal regions that may harbor genes and gene variants influencing carotid artery size in American Indian SHFS participants. We found significant genetic linkage of left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameters in chromosome 7q (lod=4.85 and 3.77, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=3.12 and 2.72, respectively, after full covariate adjustment) in Arizona SHFS participants; when left and right carotid diastolic and systolic lumen diameters were averaged, as is common in epidemiologic studies, the linkage signal was attenuated but remained significant (lod=3.26 and 3.13, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.25 and 2.73, respectively, after full covariate adjustment). Another region with suggestive evidence of linkage for left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter was found in chromosome 12q (lod=2.20 and 2.60, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.44 and 2.16, respectively, after full covariate adjustment); suggestive linkage for right carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameter was also found in chromosome 9q (lod=2.72 and 3.19, respectively, after sex and age adjustment, and lod=2.36 and 2.31, respectively, after full covariate adjustment) and suggestive linkage for left carotid artery systolic lumen diameter but not diastolic lumen diameter was found in chromosome 13 at 103 cM (lod=2.16, after full covariate adjustment) in Oklahoma SHFS participants.

We found the highest lod scores for carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameters in chromosome 7q. There are several excellent candidate genes in the region, including KCND2 or Kv4.2 (29–30). KCND or Kv4 proteins form voltage-activated Atype potassium (K+) ion channels found in smooth muscle cells of the carotid and neuroepitelithelial bodies and pulmonary arteries and are prominent in the repolarization phase of the action potential (31–32). Hypoxia leads to activation of Kv channels which then increases K+ efflux, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization, leading to closing of voltage-dependent calcium (Ca2+) channels and a decrease in Ca2+ influx ensuing arterial vasodilation (32). No other studies have shown a relation between this genetic locus and carotid artery lumen diameter. While the Framingham Heart Study found evidence of linkage with carotid intimal medial thickness in their Caucasian population on chromosome 7 (33–34), the location is different (at 161 cM); we did not find evidence of linkage with carotid intimal medial thickness in that chromosomal region (data not shown). We found no evidence of linkage for the carotid stiffness index (β) in chromosomes 7 or 9 (data not shown). The genetic locus we found to be linked to carotid artery size in this study has also been shown to be associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure in Nigerian families (35) and with body mass index in the NHLBI Family Heart Study (36). While it is possible that the attenuation of the linkage signal we observed after full covariate adjustment that included blood pressure and body size could be attributed to the association of this locus to blood pressure and body size, we did not find any linkage evidence at this locus with blood pressure or body mass index in the American Indian SHFS participants (37–39).

Our findings of chromosomal regions linked to the left but not the right carotid arterial lumen diameter and vice versa suggest lateralization in gene and variants influencing carotid arterial lumen diameter. Denarié et al. have shown that carotid arterial lumen diameter tended to be smaller on the left side than on the right side in both men and women (40). Among SHFS participants, we found left carotid arterial lumen diameters were, on average, slightly but statistically significantly smaller than the right in both sexes and across all centers. Recent studies have also indicated differing effects of shear stress and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors on left and right carotid arterial structure suggesting lateralization of specific environment-gene interactions on carotid arterial structure (41–43). Of particular relevance to our findings of significant linkage of left carotid artery diastolic and systolic lumen diameters to chromosome 7q, studies suggest that functional asymmetry exists between left and right carotid baroreceptor cardiac reflexes, with greater blood flow acceleration response to carotid baroreceptor activation/inactivation in the left than the right carotid artery (44–45). Further studies are needed to determine whether genetic factors influence functional asymmetry between left and right carotid baroreceptor cardiac reflexes.

Recent studies have provided evidence of a correlation between carotid artery lumen diameter and risk of aortic aneurysm formation in population-based samples (5–6). In the Tromsø Study, investigators found that common carotid artery lumen diameter was independently associated with an almost 2-fold risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm in men and 4-fold risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm in women, suggesting an association between carotid artery dilatation and a general arterial dilating diathesis (5). It remains unclear whether similar genes and variants influence carotid artery, thoracic aortic or abdominal aortic size. Among American Indian SHFS participants, carotid artery lumen diameter was moderately genetically correlated with aortic root diameter (ρ=0.52 to 0.58). We found no evidence of linkage for aortic root diameter in chromosome 7 among American Indian SHFS participants; abdominal aortic diameter was not evaluated in the SHFS.

Study Limitations

This study was conducted in the American Indian participants of the SHFS and thus, may not be applicable to other ethnicities. However, a recent study of multi-generational Afro-Caribbean families reported genetic linkage of carotid artery lumen diameter in chromosome 11 at 133 cM (lod=4.09) and suggestive linkage in chromosome 14 at 54 cM (lod=2.5) (46). We found no linkage of carotid artery lumen diameter in chromosome 11; we found suggestive linkage of left carotid artery lumen diameter in a different location in chromosome 14 (35 cM, lod=2.28). These findings suggest that there may be ethnic heterogeneity in genes or gene variants influencing carotid artery lumen diameter. Further studies are needed to identify genetic loci influencing carotid artery lumen diameters in other ethnicities.

Conclusion

We found significant linkage evidence for carotid artery lumen diameter on chromosome 7q and suggestive linkage peaks on chromosomes 12q and 9q. Further studies are needed to determine the genes and variants contained in these chromosomal regions that are responsible for the observed linkage results. Identification of and gene variants influencing carotid artery size in these novel chromosomal regions may provide insight into mechanisms involved in aortic aneurysm formation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Indian Health Service, the SHFS participants, and the participating tribal communities for the extraordinary cooperation and involvement that made this study possible; the SHFS center coordinators; and SHFS data coordinators and managers.

Grant Support: This study is supported by cooperative agreements U01-HL41642, HL41652, HL41654, HL65520, HL65521 and grant M10RR0047-34 (General Clinical Research Center) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Development of SOLAR is supported by grant MH059490.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the Indian Health Service.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roman MJ, Saba PS, Pini R, et al. Parallel cardiac and vascular adaptation in hypertension. Circulation. 1992;86:1909–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasonographically assessed carotid morphology and risk of coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1991;11:1245–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belcaro G, Nicolaides AN, Laurora G, Cesarone MR, De Sanctis M, Incandela L, Barsotti A. Ultrasound morphology classification of the arterial wall and cardiovascular events in a 6-year follow-up study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:851–856. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenland P, Abrams J, Aurigemma GP, et al. Prevention Conference V: beyond secondary prevention: identifying the high-risk patient for primary prevention noninvasive tests of atherosclerotic burden. Circulation. 2002;101:e16–e22. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.1.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnsen SH, Joakimsen O, Singh K, Stensland E, Forsdahl SH, Jacobsen BK. Relation of common carotid artery lumen diameter to general arterial dilating diathesis and abdominal aortic aneurysms: The Tromsø Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:330–338. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordon I, Brar R, Taylor J, Hinchliffe R, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Evidence from cross-sectional imaging indicates abdominal but not thoracic aortic aneurysms are local manifestations of a systemic dilating diathesis. J Vacs Surg. 2009;50:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roman MJ, Pickering TG, Pini R, Schwartz JE, Devereux RB. Prevalence and determinants of cardiac and vascular hypertrophy in hypertension. Hypertension. 1995;26:369–373. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North KE, MacCluer JW, Devereux RB, et al. Heritability of carotid artery structure and function: The Strong Heart Family Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1698–1703. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000032656.91352.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duggirala R, Villapando CG, O’Leary DH, Stern MP, Blangero J. Genetic basis of variation in carotid artery wall thickness. Stroke. 1996;27:833–837. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zannad F, Visvikis S, Gueguen R, et al. Genetics strongly determines the wall thickness of the left and right carotid arteries. Hum Genet. 1998;103:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s004390050804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, et al. The Strong Heart Study - a study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;13:1141–1155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard BV, Lee ET, Cowan LD, et al. The rising tide of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:2389–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.North KE, Howard BV, Welty TK, Best LG, Lee ET, Yeh JL, Fabsitz RR, Roman MJ, MacCluer JW. Genetic and environmental contributions to cardiovascular disease risk in American Indians: The Strong Heart Family Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:303–314. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bella JN, Roman MJ, Pini R, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Devereux RB. Assessment of arterial compliance by carotid midwall strain-stress relation in normotensive adults. Hypertension. 1999;33:787–792. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bella JN, Roman MJ, Pini R, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Devereux RB. Assessment of arterial compliance by carotid midwall strain-stress relation in hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:793–799. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roman MJ, Saba PS, Pini R, Spitzer M, Pickering TG, Rosen S, Alderman MH, Devereux RB. Parallel cardiac and vascular adaptation in hypertension. Circulation. 1992;86:1909–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissenbach J, Gyapay G, Dib C, et al. A second-generation linkage map of the human genome. Nature. 1992;359:794–801. doi: 10.1038/359794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dib C, Faure S, Fizames C, et al. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature. 1996;380:152–4. doi: 10.1038/380152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPeek MS, Sun L. Statistical tests for detection of misspecified relationships by use of genome-screen data. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1076–94. doi: 10.1086/302800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun L, Wilder K, McPeek MS. Enhanced pedigree error detection. Hum Hered. 2002;54:99–110. doi: 10.1159/000067666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobel E, Lange K. Descent graphs in pedigree analysis: applications to haplotyping, location scores, and marker-sharing statistics. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:1323–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobel E, Papp CJ, Lange K. Detection and integration of genotyping errors in statistical genetics. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:496–508. doi: 10.1086/338920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, et al. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;31:241–7. doi: 10.1038/ng917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boehnke M. Allele frequency estimation from data on relatives. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:22–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath SC. Markov chain Monte Carlo segregation and linkage analysis for oligogenic models. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:748–60. doi: 10.1086/515506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feingold E, Brown PO, Siegmund D. Gaussian models for genetics linkage analysis using complete high-resolution maps of identity by descent. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:234–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lander E, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex trait: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postma AV, Bezzina CR, de Vries JF, Wilde AAM, Moorman AFM, Mannens MMAM. Genomic organization and chromosomal localization of two members of the KCND ion family channel, KCND2 and KCND3. Hum Genet. 2000;106:614–619. doi: 10.1007/s004390000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu XR, Wulf A, Schwarz M, Isbrant D, Pongs O. Characterization of human Kv4. 2 mediating a rapidly-inactivating transient voltage-sensitive K+ channels. Receptors Channels. 1999;6:387–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel AJ, Honoré E. Molecular physiology of oxygen-sensitive potassium channels. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:221–227. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00204001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C, Lu Y, Tang G, Wang R. Expression of voltage-dependent K channel genes in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1999;277:1055–1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox CS, Cupples LA, Chazaro I, et al. Genomewide linkage analysis for internal carotid artery intimal medial thickness: evidence for linkage to chromosome 12. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:253–261. doi: 10.1086/381559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donnel CJ, Cupples LA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Genome-wide association study for subclincial atherosclerosis in major arterial territories in the NHLBI’s Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8:S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tayo BO, Luke A, Zhu X, Adyemo A, Cooper RS. Association of regions in chromosome 6 and 7 with blood pressure in Nigerian families. Circulation Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:38–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.817064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laramie JM, Wilk JB, Williamson SL, et al. Multiple genes influence BMI in chromosome 7q31–34: the NHLBI Family Study. Obesity. 2009;17:2182–2189. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franceschini N, MacCluer JW, Rose KM, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of pulse pressure in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:194–199. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almasy L, Göring HHH, Diego VP, et al. A novel obesity locus on chromosome 4q: The Strong Heart Family Study. Obesity. 2007;15:1741–1748. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franceschini N, Almasy L, MacCluer JW, et al. Diabetes-specific genetic effects on obesity traits in American Indian populations: the Strong Heart Family Study. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denarié N, Gariepy J, Chirmoni G, et al. Distribution of ultrasonographically-assessed dimensions of common carotid arteries in healthy adults of both sexes. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim J, Miyashiro JK, Berk BC. Shear stress is differentially regulated among inbred rat strains. Circ Res. 2003;92:1001–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069687.54486.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaubey S, Nitsch D, Altmann D, Ebrahim S. Differing effect of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors on intima-medial thickening and plaque formation at different sites of arterial vasculature. Heart. 2010;96:1579–1585. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.188219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Yang Y, Cao T, Li Z. Differences in left and right carotid intima-media thickness and the associated risk factors. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tafil-Klawe M, Raschke F, Hildebrandt G. Functional asymmetry in carotid sinus cardiac reflexes in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;60:402–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00713507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper VL, Pearson SB, Bowker CM, Elliott MW, Hainsworth R. Interaction of chemoreceptor and baroreceptor reflexes by hypoxia and hypercapnia: a mechanism for promoting hypertension in obstructive sleep apnoea. J Physiol. 2005;568:677–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuipers AL, Miljkovic E, Kammerer CM, Woodard G, Bunker CH, Patrick AL, Wheeler VW, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Zmuda J. Genome-wide linkage analysis of carotid artery ultrasound phenotypes in multi-generational Afro-Caribbean families. Abstracts from the 2011 Joint Conference – Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology and Prevention; p. 262. [Google Scholar]