Abstract

Urea and sulfonamide derivatives of 1 exhibit ON-OFF and OFF-ON switchable fluorescent and colorimetric responses upon protonation. The magnitude of the fluorescence event is dictated by the anion, resulting in a rare, fully organic “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for chloride.

A great deal of effort has been devoted to tailoring photoactive switches on the molecular level for use in applications from biological imaging to molecular logic gates and photodynamic therapy.1,2 In particular, advances in our understanding of intermolecular luminescence processes has led to elegant multicomponent supramolecular switches and probes with nanomolar sensitivity for anions, which have been the subject of many detailed reviews.3

Fluorescence as a sensing mechanism is desirable due to its inherent sensitivity and relative ease of measurement with common laboratory equipment. These sensors are often modulated by pH, with the protonation or deprotonation of incorporated heterocycles as a common fluorescence ON-OFF, or more rarely OFF-ON, switching motif.4,5 Additionally, the tunable luminescence properties of simple organic photoswitches has led to systems capable of responding to multiple inputs or outputs, which has opened the way to entirely organic logic gates.6 However, these structures are commonly engineered to exploit a single, distinct fluorescence phenomenon (e.g., polarity dependent emission shifting or PET quenching upon binding a guest) or colorimetric changes as their signaling events, and can thus be limited in the flexibility of their application. Consequently, there persists a need for selective, small-molecule organic systems with discrete, easily tunable negative and positive fluorescent responses. Herein we report the development of a compact fluorescent scaffold easily derivatized to yield switchable ON-OFF and OFF-ON responsive compounds.

Recently we reported the synthesis and halide binding studies of the parent phenylurea-substituted receptor 2 (Fig. 1) with a series of tetrabutylammonium halides.7 During the preparation and characterization of the trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) salts of the protonated receptors, we found that the fluorescence of the arylacetylene core 1 and phenylurea 2 were both quenched upon protonation in CHCl3. This occurred concurrently with a change in the solution from colorless to yellow (Fig. 2). This change in solution color is seen in the UV-visible spectrum as a charge transfer absorbance band from ca. 450–500 nm and is indicative of protonation at the pyridine nitrogen, which has been noted in similar systems.8

Fig. 1.

Structures of 2,6-bis(2-anilinoethynyl)pyridine receptor core 1 and urea (2,3a,b) and sulfonamide (4a,b) derivatives.

Fig. 2.

UV-Vis spectra of 1 and 2a as both protonated and neutral receptors ([Host] and [Host•H+] = 12 μM in CHCl3).

Due to our interest in fluorescent anion sensors, we have explored how donor/acceptor functionalization could influence the binding strengths and optoelectronic responses of the core dianiline 1. Consequently, we prepared hydrogen bonding electron-rich and electron-poor ureas 3a,b and sulfonamides 4a,b (Fig. 1). We reasoned that electron deficient receptors would possess a higher binding affinity for anionic guests and thus expected changes in fluorescence upon protonation, much like the parent compounds. In electron-rich systems 3a and 4a, protonation with TFA gave yellow solutions, and the fluorescence emission was indeed quenched (Fig. 3). In both these and the parent systems, the residual emission peak bathochromically shifted only when Cl− was present as the counterion (see ESI for spectra of 1–3a, 4a with Cl−, as well as UV-visible and excitation spectra). In the case of ureas 2•TFA and 3a•TFA, the fluorescence spectra showed a second weak, hypsochromically shifted peak below 400 nm, but this additional feature occurred only when CF3CO2− was present as the counterion.9

Fig. 3.

Normalized emission spectra of both neutral and protonated electron-rich receptors ([Host] and [Host•H+] = 12 μM in CHCl3; excitation 1: 360 nm, 2,3a,b: 343 nm; 4a: 338 nm).

In contrast to electron-rich 3a and 4a, electron-poor analogues 3b and 4b were non-fluorescent in the freebase form. Protonation with TFA also resulted in yellow solutions, but significantly increased the fluorescence maxima at ∼515–555 nm (Fig. 4). To examine the effect of the counterion, receptors 3b and 4b were then treated with gaseous HCl, as Cl− is known to bind much more strongly than CF3CO2−.10 The resultant, excimer-like fluorescence (Fig. 4, dash-dot lines) occurred at the same wavelength as the residual fluorescence in the quenched 2•TFA, 2•HCl, 3a•HCl and 4a•HCl receptors.11 These data were corroborated by the addition of Bu4NCl to the TFA-protonated receptors, which produced the same emission bands observed upon addition of gaseous HCl to the neutral receptor (i.e., bathochromic shifts in the emission bands).

Fig. 4. Emission spectra of electron-poor receptors both neutral and protonated with TFA or HCl ([Host] and [Host•H+] = 12 μM in CHCl3; excitation 3b: 360 nm, 4b: 365 nm).

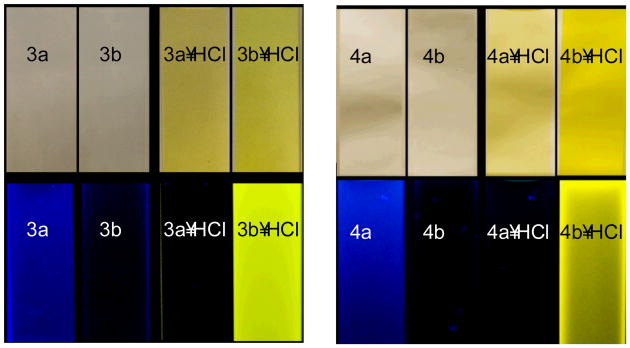

Fig. 5 visually illustrates the very simple trends observed in both the urea and sulfonamide derivatives of 1: colorless solutions turn yellow upon exposure to acid regardless of the proton source and arene substituent. Electron-donating substituents on the pendant phenyl rings afford compounds that are fluorescent (ON) in the neutral state and quenched (OFF) when protonated. On the other hand, substitution with electron-withdrawing groups furnishes a weakly fluorescent freebase receptor (OFF) with greatly enhanced fluorescence (ON) and equivalent red shifting in the emission spectra upon exposure to acids with appropriately sized conjugate bases.‡ These trends are also mirrored by the experimentally determined quantum yields in Table 1. For example, receptor 3b experiences a near full order of magnitude increase in its OFF-ON fluorescence response when Cl− is the counterion present, even when pre-protonated with TFA.

Fig. 5.

Colorless solutions of neutral compounds in CHCl3 turn yellow upon protonation (top); fluorescence (excitation 365 nm) is quenched in electron-rich systems 3a, 4a and turned “on” in electron poor systems 3b, 4b (bottom).

Table 1.

Quantum yields of the freebase and protonated receptors. a

| 1 | 2 | 3a | 3b | 4a | 4b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freebase | 2.26% | 0.3% | 8.3% | 0.09% | 3.04% | 0.16% |

| TFA | 1.84% | 0.04% | 0.05% | 2.16% | 1.02% | 0.36% |

| HCl | 1.65% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 12.6% | 0.69% | 2.14% |

Absolute photoluminescent quantum yields obtained with a Horiba-Jobin Yvon integrating sphere in O2-containing CHCl3.

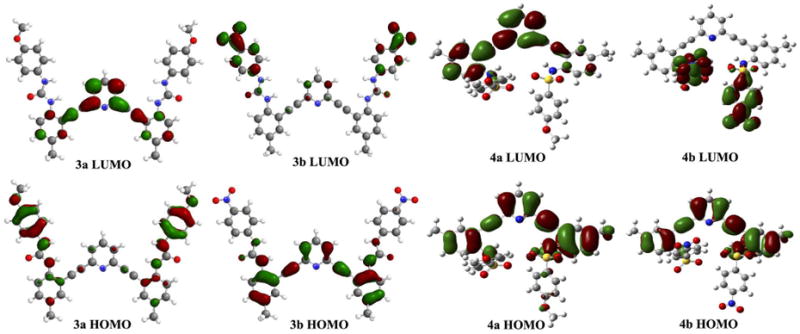

Frontier molecular orbital calculations (B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory) provide insight into the mechanisms behind the behavior of the freebase receptors.12 Compounds 3a and 4a have nearly equivalent lowest-unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) maps, while the highest-occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) maps are significantly different, although still overlap with the LUMO on the tri-substituted arene rings (Fig. 6). In both, excitation retains electron density near the central alkynyl system, resulting in radiative de-excitation and thus fluorescence. In 3b and 4b, however, a charge-transfer fluorescence state is generated, resulting in quenched fluorescence, similar to other known arylacetylene scaffolds.12 The fluorescence OFF-ON response seems to be intramolecularly excimeric in nature, with this emission having an intriguing dependence on counterion, which warrants further study.

Fig. 6.

Calculated frontier molecular orbitals for neutral ureas 3a,b and sulfonamides 4a,b. Non-overlapping HOMO and LUMO orbitals in the electron-acceptor substituted systems results in charge transfer quenching of the neutral receptors.

In conclusion, we have disclosed the development of a receptor scaffold with switchable “ON-OFF” or “OFF-ON” fluorescence based upon judicious choice of the pendant phenyl functionalities. Remarkably, these results indicate that this class of receptors can function as a positive response (OFF-ON) fluorescent indicator for chloride ion, which augurs well for applications in cellular ion staining applications and molecular probe design.1 Additionally, the occurrence of both a colorimetric and switchable fluorescent ON-OFF or OFF-ON response in a single class of compounds is promising for application in molecular logic systems, where they could conceivably function as complex gates, e.g., INHIBIT or enabled OR operators. Binding studies with simple biological anions, epifluorescence studies and further modifications of receptor structures are currently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (GM087398-01A1) and the University of Oregon (UO). C.N.C., O.B.B and S.P.M. acknowledge the NSF for Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeships (DGE-0549503). C.A.J. thanks UO for a Doctoral Research Fellowship. D.W.J. is a Cottrell Scholar of the Research Corporation for Science Advancement.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details for 3a,b and 4a,b; UV-visible and excitation spectra of the HCl-protonated receptors 1, 2, 3a,b; emission spectra of HBr-protonated receptors 3a,b and 4a,b; complete ref. 12a. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

The addition of HNO3 or camphorsulfonic acid results in the protonation of the receptor by UV-Vis, but does not result in an increase in fluorescence in receptors 3b or 4b. We tentatively attribute this to the size difference of these anions compared to Cl−, which precludes the formation of either the “U” conformation reported in ref. 7 or dimeric species seen in O. B. Berryman, C. A. Johnson II, L. N. Zakharov, M. M. Haley, and D. W. Johnson, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 117.

Contributor Information

Darren W. Johnson, Email: dwj@uoregon.edu.

Michael M. Haley, Email: haley@uoregon.edu.

References

- 1.For reviews of small molecule biological imaging see: Kikuchi K. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:2048. doi: 10.1039/b819316a.Carroll CN, Naleway J, Haley MM, Johnson DW. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:3875. doi: 10.1039/b926231h.

- 2.For reviews of molecular logic see: Mirkin CA, Ratner MA. Molecular Electronics. Vol. 43 Annual Reviews, Inc.; 1992. Feringa BL. Molecular Switches. Wiley-VCH GmbH; Weinheim, Germany: 2001. Montalban AG, Baum SM, Barrett AGM, Hoffman BM. Dalton Trans. 2003;2093Norum OJ, Selbo PK, Weyergang A, Giercksky KE, Berg K. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2009;96:83. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.04.012.

- 3.(a) Themed issue in supramolecular chemistry of anions and references therein: Gale PA, Gunnlaugsson T. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:3595.; Valeur B. Molecular Fluorescence. Vol. 273 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH; Weinheim, Germany: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Fabbrizzi L, Gatti F, Pallavicini P, Parodi L. New J Chem. 1998;1403 [Google Scholar]; (b) Shizuka H, Tobita S. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6919. [Google Scholar]; (c) Clements JH, Webber SE. Macromolecules. 2004;37:1531. [Google Scholar]; (d) de Silva AP, Nimal Gunaratne HQ, McCoy CP. Chem Commun. 1996:2399. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) De Santis G, Fabrizzi L, Licchelli M, Poggi A, Taglietti A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:202. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gunnlaugsson T, Davis AP, O'Brien JE, Glynn M. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:48. doi: 10.1039/b409018g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Garcîa-Garrido SE, Caltagirone C, Light ME, Gale PA. Chem Commun. 2007:1450. doi: 10.1039/b618072h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Dickson SJ, Swinburne AN, Paterson MJ, Lloyd GO, Beeby A, Steed JW. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2009:3879–3882. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roque A, Pina F, Alves S, Ballardini R, Maestri M, Balzani V. J Mater Chem. 1999;9:2265. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll CN, Berryman OB, Johnson CA, II, Haley MM, Johnson DW. Chem Commun. 2009:2520. doi: 10.1039/b901643k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heemstra JM, Moore JS. Org Lett. 2004;6:659–662. doi: 10.1021/ol0363016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protonation of the receptors with HBr resulted in mixed emission bands at both ∼404 nm and ∼515 nm. See the ESI.

- 10.The binding preference for Cl− over CF3CO2− can be inferred from the magnitude of the binding constant for Cl− with 2•TFA from ref. 7.

- 11.See ESI for spectra of these receptors (2, 3a, 4a) with gaseous HCl.

- 12.(a) Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03. Gaussian, Inc; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. Revision B.04. Full reference in ESI. [Google Scholar]; (b) Spartan 08. Wavefunction, Inc.; Irvine, CA, USA: [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Marsden JA, Miller JJ, Shirtcliff LD, Haley MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2464. doi: 10.1021/ja044175a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zucchero AJ, Wilson JN, Bunz UHF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11872. doi: 10.1021/ja061112e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Spitler EL, Shirtcliff LD, Haley MM. J Org Chem. 2007;72:86. doi: 10.1021/jo061712w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zucchero AJ, McGrier PL, Bunz UHF. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:397. doi: 10.1021/ar900218d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.