Abstract

Existing stereotypes about Black Americans may influence perceptions of intent during financial negotiations. In this study, we explored whether the influence of race on economic decisions extends to choices that are costly to the decision maker. We investigated whether racial group membership contributes to differential likelihood of rejection of objectively equal unfair monetary offers. In the Ultimatum Game, players accept or reject proposed splits of money. Players keep accepted splits, but if a player rejects an offer, both the player and the proposer receive nothing. We found that participants accepted more offers and lower offer amounts from White proposers than from Black proposers, and that this pattern was accentuated for participants with higher implicit race bias. These findings indicate that participants are willing to discriminate against Black proposers even at a cost to their own financial gain.

Keywords: decision making, implicit race bias, behavioral economics, Ultimatum Game, racial and ethnic attitudes and relations, intergroup dynamics, prejudice, social behavior

Decision-making researchers in the 20th century initially emphasized two tenets: that individuals (a) are rational in their decisions and (b) are motivated to maximize their own financial gain (Becker, 1978; Downs, 1957). During the evolution of judgment and decision-making science, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) began to challenge assumptions of a rational, utility-maximizing decision maker (Dawes & Thaler, 1988). It became clear that a host of psychological and emotional factors color the decision process, resulting in decision biases (Camerer & Loewenstein, 2004; Kahneman & Tversky, 2000; Loewenstein & Lerner, 2003). One prominent factor in many everyday interactions that may influence the decision process and compromise its rationality is racial group membership.

When individuals are free to allocate resources as they see fit, they generally make equitable offers to in-group and out-group members (Jetten, Spears, & Manstead, 1996; Jost & Azzi, 1996). However, the degree of equity in offers to members of racial out-groups varies as a function of participants’ race bias, such that individuals with stronger implicit race bias are less equitable (Stanley, Sokol-Hessner, Banaji, & Phelps, 2011). Other studies have shown that when forced to allocate resources, or when responding to allocated offers, people favor in-group over out-group members (Diekmann, Samuels, Ross, & Bazerman, 1997; Tajfel, 1970). The economic decisions in these studies, however, were made at no cost to the decision makers. When personal gain is at stake, people may be even less equitable. The goal of the present research was to determine whether discrimination in economic decisions would ever occur at the expense of personal financial gain.

Because there exist cultural associations of Black American males with aggression, hostility (Dovidio, Brigham, Johnson, & Gaertner, 1996), and untrustworthiness (Dotsch, Wigboldus, Langner, & van Knippenberg, 2008), individuals may be more likely to perceive a low financial offer as unfair when the offer comes from a Black rather than White individual. To study whether self-interest will be set aside because of stereotypic and prejudicial associations, we sought to create an economically costly situation in which the race of the individual players varied. Economically costly decisions have been observed in the Ultimatum Game, in which one player (i.e., the proposer) is endowed with a sum of money at the beginning of each round and decides how to divide up the money between him- or herself and another player (i.e., the responder). The responder can then accept the proposed split or reject it. If the responder accepts the split, the money is divided according to the proposer’s offer. If he or she rejects the offer, both players get nothing. Responders reject low offers (~20% of the total endowment) half the time, even when the economically maximizing strategy is to accept them (Bolton & Zwick, 1995; Sanfey, Rilling, Aronson, Nystrom, & Cohen, 2003; Thaler, 1988). This occurs, in part, because responders punish proposers for unfair treatment (Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996). Thus, perceptions of fairness in the Ultimatum Game are inversely related to the likelihood of rejecting an offer.

The focus of the research reported here was on how differential levels of group-based trust influence economic decision making. Lower levels of trust (Dotsch et al., 2008) in the motives of Black Americans and stereotypes of aggression and hostility (Dovidio et al., 1996) may cause individuals to perceive a low financial offer as more unfair when it comes from a Black rather than a White proposer. Therefore, objectively identical low offers may be rejected more often when offered by a Black than a White proposer, and it may require larger offer amounts for responders to accept Black proposers’ offers. If race-based associations guide responding to offers, participants with stronger negative race associations should be more likely to exhibit race bias in accepting offers (Stanley et al., 2011), even when this increases their personal cost.

Method

Participants

Forty-nine (28 females, 21 males) native English-speaking individuals participated in exchange for $10 and received additional compensation based on the outcome of their Ultimatum Game responses (for a priori exclusion criteria, see Information on Participants and Other-Race Analyses in the Supplemental Material available online). The ethnic-racial distribution of the sample was as follows: 27 Whites, 6 Black Americans, 6 Asians, 1 Hispanic, 2 Middle Easterners, 6 biracial or multiracial individuals, and 1 other-race individual. Participants were recruited from the New York University campus and surrounding community.

Procedure

Ultimatum Game

Participants always played the role of the responder. On each trial, participants ostensibly played with a new proposer whom they were told had participated in a previous Ultimatum Game experiment (see Procedural Details and Supplemental Discussion in the Supplemental Material). The proposers varied by race (60 White males, 60 Black males, and 40 other-race males of Asian, Middle Eastern, and Hispanic descent; photographs of the proposers were shown in color). Because aggression, hostility, and untrustworthiness are more closely linked to Black American males than females, for this initial exploration, all proposers were male (Sesko & Biernat, 2010). Other-race proposers were included to decrease participants’ awareness that the experiment was about responses to Black versus White proposers.1 Offers were always splits of $10. Across the three proposers’ racial groups, the distribution and mean of the offers were equivalent (offer range: $0–$3.80, M = $1.94, SD = $0.99). Participants were told that if they accepted an offer, they would receive that payout and that the researchers would mail the proposer a check for his share of the money. Players had 4 s to decide on each offer; following a decision, the intertrial interval was 1 to 5 s (duration randomly selected). If they failed to respond within 4 s, a warning message appeared, requesting that they respond faster, and then the study automatically advanced to the next trial. The final payouts were based on three randomly selected trials (maximum possible outcome = $11.40).

To reinforce the believability of the social exchange, we told participants during the introduction that their picture would be taken at the end of the experiment and that they would make five offers to be used as proposals for future participants. Participants’ contact information was collected at the end of the experiment, and they were told that if future responders accepted their offers, we would mail them a check for their winnings. Before beginning the experiment, participants took a short quiz to verify their understanding of the game rules.

To estimate response functions for the Ultimatum Game, we used a logistic function to fit the slope and point of indifference between accepting and rejecting an offer, separately for each individual participant’s data. The slope allows for estimation of the participant’s sensitivity to the fairness of the offers, and the point of indifference allows for estimation of the offer amount at which a participant is as likely to accept as to reject an offer. Changes in the proportions of acceptance across offer amounts were modeled using a using a maximum likelihood method:

The acceptance rate is determined by both m, the slope, and D, the point of indifference for each subject (x is the offer size). Scrutiny of these data revealed separation in the fitting of the logistic function. To reduce bias in the estimation and allow for finite parameter estimates, we performed logistic function estimation (logistf function in R) using Firth's (1993) penalized-likelihood logistic regression. Additionally, the proportion of offers accepted and response latencies were calculated after removal of timed-out trials.

Implicit race bias

After the decision-making task, participants completed an Implicit Association Test (IAT) that measured their strength of association between races (Black/White) and attributes (pleasant/unpleasant). Using the procedures described by Lane, Banaji, Nosek, and Greenwald (2007), we asked participants to respond accurately and rapidly with a right-hand key press to items from one race and one attribute category (e.g., “Black” and “unpleasant”), and with a left-hand key press to items from the remaining two categories (e.g., “White” and “pleasant”). During evaluation-incongruent blocks, “Black” and “pleasant” (e.g., terrific, nice) items shared a labeled response key, and “White” and “unpleasant” (e.g., terrible, foul) items shared a labeled response key. During evaluation-congruent blocks, these pairings were switched.

Participants’ IAT D scores were calculated using the algorithm developed by Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003). D scores greater than 0 indicate pro-White bias (i.e., faster response latencies when “White” and “pleasant” were paired than when “Black” and “pleasant” were paired).

The IAT D score has a possible range of −2 to +2 (Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, 2002). White participants on average have IAT scores above 0; however, non-White participants, although more variable in their D scores, can similarly show pro-White IAT bias (Nosek et al., 2002). This is because participants of different racial groups have been exposed to similar racial stereotypes. Although participants—non-White as well as White—may not explicitly endorse these stereotypes, this exposure to cultural attitudes can still influence their behavior through implicit channels (Lane et al., 2007). Therefore, to increase the between-subjects variance and to allow for estimation across the full range of D scores, we included all participants in the analyses (see Stanley et al., 2011, for a similar practice). However, we also report results of analyses of subsamples, which confirmed that non-Black and White participants showed effects in the same direction as those observed for the entire sample; we report these analyses with a note of caution regarding the reduction in statistical power due to decreases in sample size.

Results

Acceptance rates

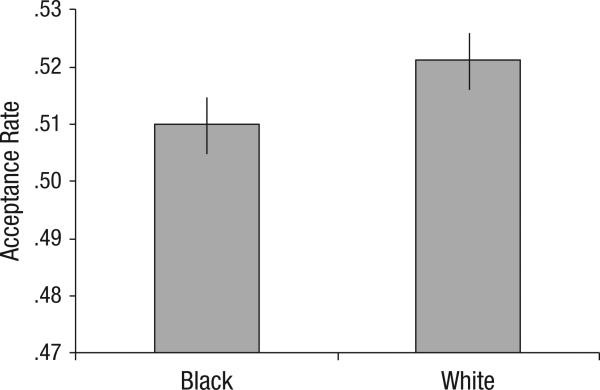

To assess how racial group membership of the proposer affects responding during the Ultimatum Game, we compared acceptance rates for Black and White proposers independent of the participant's race. The overall acceptance rate across all offers was .52 (range: .11–.93, SD = .22). Analyses revealed significantly greater acceptance of White compared with Black proposers’ offers, F(1, 48) = 5.48, p = .02, ηp2 = .10 (Fig. 1).2

Fig. 1.

Acceptance rate as a function of proposer's race. Error bars represent ±1 SE.

The overall acceptance rate among non-Black participants was .48 (range: .11–.91, SD = .23).3 Results revealed significantly greater acceptance rates for White proposers’ offers (M = .49) compared with Black proposers’ offers (M = .48) in this subsample, F(1, 35) = 4.84, p = .04, ηp2 = .12.4 The overall acceptance rate for the White participants was .44 (range: .11–.91, SD = .22). Among White participants, the difference in acceptance rates between Black (M = .44) and White (M = .45) proposers failed to reach significance because of a substantial loss of power, F(1, 26) = 2.34, p = .14, ηp2 = .08, although it was directionally similar to the effect obtained for the full sample and for non-Black participants.

Modeling behavior

To explore participants’ sensitivity to the fairness of offers and to determine the offer amount required for participants to accept an offer, we fit data using a logistic function. From the logistic curve, each participant's slope and point of indifference (probability of acceptance = .5) were estimated, and these values were compared between the two races of proposers. Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) revealed different slopes, F(1, 48) = 4.58, p = .04, ηp2 = .09, and points of indifference, F(1, 48) = 12.45, p < .01, ηp2 = .21, between Black and White proposers (Table 1). Participants had steeper slopes for Black proposers than for White proposers, which suggests that participants were more sensitive to small changes in the offer amount when offers came from Black proposers, and were flexible in their decisions across a wider range of offers for White proposers. Additionally, participants’ points of indifference were greater for Black than for White proposers; larger offer amounts were required for players to accept offers from Black proposers.

Table 1.

Results From Individual Estimates of Participants’ Response Functions: Means and Standard Deviations for Slopes and Points of Indifference

| Slope |

Point of indifference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race of proposer | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Black | 8.78 | 5.19 | 1.86 | 0.75 |

| White | 7.60 | 4.50 | 1.81 | 0.76 |

Note: Means for both slope and point of indifference differed significantly between Black and White proposers, p < .05.

The repeated measures ANOVAs for the non-Black participants revealed significantly different slopes, F(1, 35) = 4.54, p = .04, ηp2 = .12, and points of indifference, F(1, 35) = 6.78, p = .01, ηp2 = .16, between Black and White proposers. Participants had steeper slopes for Black (M = 9.56) than for White (M = 8.07) proposers. Additionally, individuals’ points of indifference were greater for Black proposers (M = 1.90) than for White proposers (M = 1.86). The ANOVAs for White participants also revealed different slopes, F(1, 26) = 5.08, p = .03, ηp2 = .16, and points of indifference, F(1, 26) = 4.26, p = .05, ηp2 = .14, between Black and White proposers. Participants had steeper slopes for Black (M = 10.01) than for White (M = 8.31) proposers. Additionally, individuals’ points of indifference were greater for Black (M = 2.05) than for White (M = 2.01) proposers.

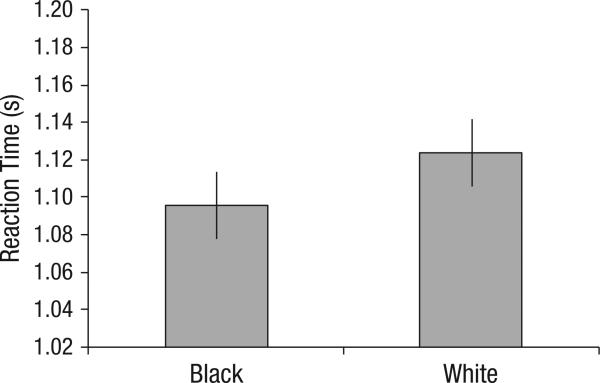

Response latency

If race attitudes guide responding, it may be the case that participants employed a dichotomizing strategy when responding to Black proposers’ offers, allowing underlying evaluations, and not deliberate consideration of each individual offer, to drive decisions. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed log response times as a function of proposer's race across all offers. Results supported the hypothesis that participants spent less time considering Black proposers’ offers, as they were faster to accept offers from Black (M = 1.10 s) than from White (M = 1.12 s) proposers, F(1, 48) = 66.77, p < .01, ηp2 = .58 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Reaction time as a function of proposer's race. For ease of interpretation, this figure depicts raw reaction times, but all analyses were performed on log-transformed reaction times. Error bars represent ±1 SE.

Non-Black participants were faster to make decision about offers from Black (M = 1.13 s) than from White (M = 1.15 s) proposers, F(1, 35) = 42.50, p < .01, ηp2 = .55. White participants were also faster to accept offers from Black (M = 1.17 s) than from White (M = 1.20 s) proposers, F(1, 26) = 25.43, p < .01, ηp2 = .49.

Acceptance rates and implicit race bias

To further explore what factors predict racial bias in acceptance rates (i.e., accepting more offers from White than from Black proposers), we conducted hierarchical regression modeling examining four factors: (a) race bias in point of indifference (i.e., how much lower the point of indifference is for White vs. Black proposers), (b) IAT D scores, (c) race bias in reaction time (i.e., how much faster responses are to Black vs. White proposers’ offers), and (d) race bias in offer sensitivity (i.e., how much steeper the slope is for Black vs. White proposers).5 In Step 1, race bias in the point of indifference was the independent variable. In Step 2, D scores were added as a predictor. In Step 3, bias in reaction time was added as a third independent variable. In the final step, race bias in offer sensitivity was added as a fourth independent variable. We examined collinearity prior to hierarchical modeling, and tolerances were above .87.

Step 1 revealed a significant relationship between point of indifference and race bias in acceptance rates (β = 0.86), t(48) = 11.50, p < .01, r2 = .74. When implicit bias (IAT D score) was added as a predictor, it predicted race bias in acceptance rates over and above the effect of point of indifference (β = 0.22), t(48) = 3.21, p < .01, pr2 = .18. Moreover, including implicit bias as a predictor in the model accounted for 4.8% of additional variance in acceptance rates, Δr2 = .048, ΔF(1, 46) = 10.33, p < .01. The addition of reaction time bias and race bias in slopes did not account for additional variance in acceptance rates, and neither emerged as a significant predictor in the full, non-Black, or White sample. These results indicate that, perhaps not surprisingly, participants who require larger offer amounts to accept Black, compared with White, proposers’ offers also accept fewer offers from Black proposers. Additionally, greater implicit bias as measured with the IAT, controlling for the other factors, predicts accepting fewer offers from Black compared with White proposers.

Discussion

The ordinary functioning of social and economic life consists of innumerable interactions in which one human being makes an offer to another, and the offer must be accepted or rejected. The recipient of the offer, if rational, should evaluate the objective quality of the offer and maximize personal gain. However, as previous research has shown, other factors can and do intervene to erode the rational interpretation of an offer. Rejecting low offers is always irrational, but the level of irrationality increases when people reject even larger offers because of the proposer's race. In the experiment reported in this article, we found that (a) the race of the proposer intervened to erode the rationality of participants’ decisions and (b) participants’ implicit race bias was predictive of their likelihood of accepting offers. Furthermore, players seemed to use a different strategy when responding to Black proposers compared with White proposers, as indicated by the consideration of a smaller range of offers and faster decisions in the former case. Note that racial bias in offer decisions was evident even though it was detrimental to participants’ personal financial gain.

In the Ultimatum Game, rejection of unfair offers is correlated with anger ratings (Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996) and physiological arousal (van 't Wout, Kahn, Sanfey, & Aleman, 2006). Because we did not directly assess participants’ motivations or emotions, it is difficult to verify that they were motivated by anger to punish Black proposers. But, given that unfair offers elicit anger (Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996) and Black Americans are stereotyped as aggressive, hostile (Dovidio et al., 1996), and untrust-worthy (Dotsch et al., 2008), participants may have had increased anger toward Black proposers’ unfair offers (see Procedural Details and Supplemental Discussion in the Supplemental Material).

Social psychological theories extend self-interest to the in-group (Brewer, 1979; Sidanius, Pratto, & Mitchell, 1994; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Although the research reported here focused primarily on how stereotypes of Black Americans influence decision making in the Ultimatum Game, an alternative explanation for why we observed greater acceptance of White proposers’ offers is that participants extended self-interest motives to their in-group. At first glance, White participants’ data support the assertion that in-group interests may have motivated White participants to accept more offers from White proposers. However, when analyzing the data for the other-race proposers, we found that the results were largely similar for White and other-race proposers (see Information on Participants and Other-Race Analyses in the Supplemental Material). Therefore, although an alternative explanation for our main findings is that group membership drove the differences, the similarity in the effects between White and other-race proposers suggests that the observed effects for White versus Black proposers arose because of the stereotypes or prejudices associated with Black Americans.

It is especially surprising that participants were willing to accrue a financial cost in order to discriminate given that race bias was less prevalent in our sample than in the general population (Nosek et al., 2007; 69.4% of our participants reported liberal attitudes, 91.7% were younger than 30, and 91.8% had completed some form of higher education). In a different sample, one might observe even greater degrees of race bias in these types of economic decisions. It should be noted that the cost to the participants was relatively low (i.e., a maximum cost of $11.40). It may be the case that as cost to participants increases, they become less likely to reject offers.

A willingness to forgo gain to punish Black proposers has extremely important social, economic, and political consequences, especially in negotiation situations. Studies have shown that race influences a variety of decisions, including guilt decisions, legal decisions, political decisions, and medical decisions (Green et al., 2007; Rooth, 2010; Sabin, Nosek, Greenwald, & Rivara, 2009; Snipes et al., 2011), but this is the first demonstration of discrimination occurring with a direct financial cost. Although our experiment tested bias in interpersonal interactions in the specific context of the Ultimatum Game, we believe that the psychological principles at play are quite general in other decisions in which violations of fairness are punished even at the expense of personal gain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ari Meilich for help with data collection and Jackie Reitzes for comments on the manuscript.

Funding This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to E. A. Phelps (MH08756 and AG039238).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J. T. Kubota and J. Li developed the study concept. All authors contributed to the study design. Testing and data collection were performed by J. T. Kubota, J. Li, and E. Bar-David. J. T. Kubota and J. Li performed the data analysis and interpretation under the supervision of M. R. Banaji and E. A. Phelps. J. T. Kubota drafted the manuscript, and J. Li, M. R. Banaji, and E. A. Phelps provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information may be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

Results for the other-race proposers were not the focus of this experiment. Attitudes and stereotypes about racial groups vary, and the groups included in the other-race category (Asian, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern) are in some instances associated with nonoverlapping stereotypes and prejudices. Interested readers should see Information on Participants and Other-Race Analyses in the Supplemental Material for exploratory analyses of the data for other-race proposers.

Three participants (2 White and 1 Asian) accepted nearly all offers and were excluded from the analyses (see Information on Participants and Other-Race Analyses in the Supplemental Material). One participant accepted every offer from White and other-race proposers and 98% of the offers from Black proposers, 1 participant accepted every offer from White and Black proposers and 98% of the offers from other-race proposers, and 1 participant accepted every offer from all proposers.

We excluded from the non-Black group participants who reported their race as “other” or who reported that they were multiracial, to ensure that this subsample was non-Black. Other-race and multirace participants were not asked for more specific information on their racial identification.

The fact that the pattern of results remained across each sub-sample lends further support to the reliability and stability of these effects. Although a few of the analyses failed to reach significance when we parsed the sample, this can be attributed to the large reduction in power (i.e., 49 participants in the overall sample dropped to 27 participants in the White-only sample).

It is important to sample the full range of IAT scores when assessing a correlation. So as not to restrict the range of data, we examined the regressions across all participants and did not analyze the data by subsample.

References

- Becker GS. The economic approach to human behavior. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton GE, Zwick R. Anonymity versus punishment in ultimatum bargaining. Games and Economic Behavior. 1995;10:95–121. doi:10.1006/game.1995.1026. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer CF, Loewenstein G. Behavioral economics: Past, present, future. In: Camerer CF, Loewenstein G, Rabin M, editors. Advances in behavioral economics. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2004. pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes RM, Thaler RH. Anomalies: Cooperation. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1988;2(3):187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann KA, Samuels SM, Ross L, Bazerman MH. Self-interest and fairness in problems of resource allocation: Allocators versus recipients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1061–1074. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotsch R, Wigboldus DHJ, Langner O, van Knippenberg A. Ethnic out-group faces are biased in the prejudiced mind. Psychological Science. 2008;19:978–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02186.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Brigham JC, Johnson BT, Gaertner SL. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination: Another look. In: Macrae CN, Stangor C, Hewstone M, editors. Stereotypes and stereotyping. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 276–292. [Google Scholar]

- Downs A. An economic theory of democracy. Harper & Row; New York, NY: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Spears R, Manstead ASR. Intergroup norms and intergroup discrimination: Distinctive self-categorization and social identity effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:1222–1233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Azzi AE. Microjustice and macrojustice in the allocation of resources between experimental groups. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;136:349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lane KA, Banaji MR, Nosek BA, Greenwald AG. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: What we know (so far) about the method. In: Wittenbrink B, Schwarz N, editors. Implicit measures of attitudes. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 59–102. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Lerner JS. The role of affect in decision making. In: Davidson R, Goldsmith H, Scherer K, editors. Handbook of affective science. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2003. pp. 619–642. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Banaji MR, Greenwald AG. Harvesting intergroup attitudes and stereotypes from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2002;6:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Hansen JJ, Devos T, Lindner NM, Ranganath KA, Banaji MR. Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology. 2007;18:36–88. doi:10.1080/10463280701489053. [Google Scholar]

- Pillutla MM, Murnighan JK. Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1996;68:208–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth D-O. Automatic associations and discrimination in hiring: Real world evidence. Labour Economics. 2010;17:523–534. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2009.04.005. [Google Scholar]

- Sabin JA, Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20:896–913. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0185. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfey AG, Rilling JK, Aronson JA, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD. The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game. Science. 2003;300:1755–1758. doi: 10.1126/science.1082976. doi:10.1126/science.1082976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesko AK, Biernat M. Prototypes of race and gender: The invisibility of Black women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:356–360. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Pratto F, Mitchell M. In-group identification, social dominance orientation, and differential intergroup social allocation. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;134:151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Snipes S, Sellers S, Tafawa A, Cooper L, Fields J, Bonham V. Is race medically relevant? A qualitative study of physicians’ attitudes about the role of race in treatment decision-making. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-183. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/11/183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley DA, Sokol-Hessner P, Banaji MR, Phelps EA. Implicit race attitudes predict trustworthiness judgments and economic trust decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2011;108:7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014345108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American. 1970;223:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin W, editors. Psychology of inter-group relations. Nelson; Chicago, IL: 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler RH. Anomalies: The Ultimatum Game. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1988;2(4):195–206. [Google Scholar]

- van ’t Wout M, Kahn RS, Sanfey AG, Aleman A. Affective state and decision-making in the Ultimatum Game. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;169:564–568. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0346-5. doi:10.1007/s00221-006-0346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.