Abstract

Objectives

If approved for use in young males in the United States, prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine may reduce the incidence of HPV-related disease in vaccinated males and their sexual partners. We aimed to characterise heterosexual men’s willingness to get HPV vaccine and identify correlates of vaccine acceptability.

Methods

Participants were from a national sample of heterosexual men (n=297) aged 18–59 y from the United States who were interviewed in January 2009. We analysed data using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Most men had not heard of HPV prior to the study or had low HPV knowledge (81%; 239/296). Most men had heard of HPV vaccine prior to the study (63%; 186/296) and 37% (109/296) were willing to get HPV vaccine. Men were more willing to get vaccinated if they reported higher perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.17), perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.83) or anticipated regret if they did not get vaccinated and an HPV infection later developed (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.89). Acceptability was also higher among men who thought (OR 9.02, 95% CI 3.45 to 23.60) or who were unsure (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.30 to 5.47) if their doctor would recommend they get HPV vaccine if licenced for males.

Conclusions

Men had low HPV knowledge and were moderately willing to get HPV vaccine. These findings underscore the need for HPV educational efforts for men and provide insight into some of the factors that may affect the HPV vaccination decision making process among men.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is common among men, with most studies reporting prevalence levels of at least 20%.1,2 Approximately 75% of infections clear within 1 year,3 but men infected with HPV still face potentially severe health consequences. Oncogenic HPV types (mainly types 16 and 18) may be responsible for up to 63% of oropharyngeal cancers, 93% of anal cancers and 36% of penile cancers in the United States.4 Genital warts are primarily attributable to infection with nononcogenic HPV types 6 and 11.5 Men infected with HPV also put their female partners at increased risk for cervical disease.6,7

The United States has approved a quadrivalent HPV vaccine against types 6, 11, 16 and 18 for use in females aged 9–26 y to protect against cervical cancer and genital warts.8 Research suggests the vaccine may also reduce the incidence of persistent HPV infection and genital warts among young men not infected with HPV types included in the vaccine.9,10 Statistical models differ as to whether vaccinating males against HPV will be cost-effective, with more favourable conclusions reached when models accounted for diseases in addition to cervical cancer in females or HPV-related diseases in males.11,12 A US Food and Drug Administration advisory panel recently recommended approving HPV vaccine for males aged 9–26 y,13 although formal Food and Drug Administration approval has not yet occurred.

For optimal public health benefit, HPV vaccination should occur before first sexual intercourse.14 The population-level benefit of vaccinating adult men against HPV is unknown and may not outweigh the costs. However, if HPV vaccine is licenced for adolescent males, adult men will still have to decide whether ‘off-label’ vaccination offers potential individual benefits that outweigh out-of-pocket costs. Similar off-label HPV vaccination is already occurring among adult women in the United States.15 Thus, it is of interest to examine HPV vaccine acceptability among adult men. HPV vaccine acceptability among college students or other convenience samples of adult men has previously ranged from modest (33%–48%) to relatively high (78%).16–18

In this study, we aimed to characterise correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men. We focused on constructs from health behaviour theories and previous research on HPV vaccine among adult women, parents and adolescent females.19

METHODS

Study design

We interviewed men aged 18–59 y who were members of an existing national panel of US households maintained by Knowledge Networks (Menlo Park, California, USA) in January 2009. Knowledge Networks identified prospective panel members using list-assisted, random-digit dialing. Households containing one or more panel members receive free internet access for completing multiple internet-based surveys each month. Panel members with existing computer and internet access accumulate points for completing surveys, which can be redeemed for small cash payments.

About 70% (609/874) of men invited to participate completed this cross-sectional, online survey.20 We report data from self-identified heterosexual men (n=297), as results for the oversample of gay and bisexual men have been reported elsewhere.21 The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina approved the study.

Measures

The University of North Carolina Men’s Health Survey is available online at http://www.unc.edu/~ntbrewer/hpv.htm. We developed survey items based on our previous HPV vaccine research with women, parents and healthcare providers.22–24 We cognitively tested the survey with 28 men to gain an initial sense of item clarity and men’s familiarity with HPV and HPV vaccine. After refining the survey, we further tested it with eight additional men prior to the study.

The survey measured HPV vaccine acceptability using five items assessing how willing a participant would be to get HPV vaccine if it were approved for males (α=0.96). Response options were ‘definitely not willing,’ ‘probably not willing,’ ‘not sure,’ ‘probably willing’ and ‘definitely willing.’ We classified each participant as either ‘willing to get HPV vaccine’ (responded probably or definitely willing to three or more items) or ‘not willing to get HPV vaccine.’

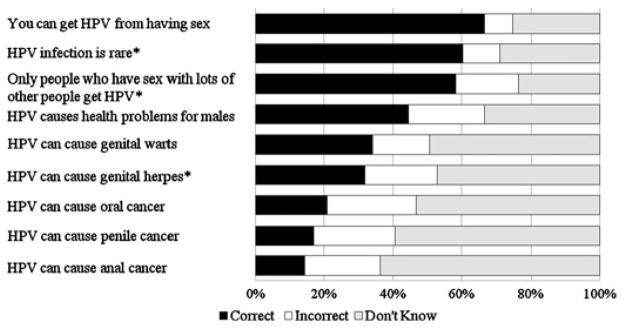

The survey measured HPV awareness by asking participants if they had ever heard of HPV prior to the survey. We calculated an HPV knowledge score by summing correct responses to nine individual items (each correct answer was one point) asked only of men who had heard of HPV (figure 1). For analyses, we classified participants as ‘unaware of HPV’ if they had never heard of HPV, aware of HPV with ‘low knowledge’ if they had heard of HPV but answered four or less knowledge items correctly or aware with ‘high knowledge’ if they had heard of HPV and answered at least five knowledge items correctly.

Figure 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge among heterosexual men who had heard of HPV prior to survey (n=182). Note. Correct answer is yes, except for items with superscript (*).

Men next received statements about HPV and HPV vaccine, although the software prevented them from returning to HPV knowledge items. The provided statements addressed HPV as being a common sexually transmitted infection (STI), diseases associated with HPV and that a vaccine exists to protect women against cervical disease. A later statement (provided prior to the willingness items) informed participants that HPV vaccine may also provide health benefits to males. The survey assessed awareness of the vaccine by asking participants if they had heard of it prior to the survey. Participants indicated whether they or any family members or friends had ever received any doses of HPV vaccine. The survey assessed whether participants had talked to a doctor about getting HPV vaccine for themselves and if they thought their doctors would recommend they get the vaccine if it were approved for males.

The survey measured perceived potential barriers (eg, cost, adverse effects) to obtaining HPV vaccine using a four-item scale (possible range 1–5; α=0.68) with response options for each item ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely.’ The survey assessed perceived effectiveness of the vaccine against HPV-related disease (four items, possible range 1–5, α=0.94) and perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease (four items, possible range 1–5, α=0.91) using multi-item scales. HPV-related diseases addressed in these scales were genital warts, anal cancer, oral cancer and penile cancer. Response options ranged from ‘no protection’ to ‘complete protection’ for effectiveness items and ‘no chance’ to ‘certain I will get [HPV-related disease]’ for likelihood items.

The survey also used multi-item scales to measure perceived knowledge of HPV-related disease (three items, possible range 1–4, α=0.69), level of concern about getting HPV-related disease (three items, possible range 1–4, α=0.51), perceived severity of HPV-related disease (three items, possible range 1–4, α=0.73) and anticipated regret of not getting HPV vaccine and later developing genital warts or an HPV infection that could lead to cancer (two items, possible range 1–4, α=0.93). HPV-related diseases addressed in the perceived knowledge, concern and perceived severity scales were genital warts, anal cancer and oral cancer. Perceived knowledge response options ranged from ‘nothing at all’ to ‘quite a lot,’ while concern, perceived severity and anticipated regret items had response options ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘quite a lot.’

Participants provided information on demographic and health-related variables (table 1). We defined ‘urban’ as living in a metropolitan statistical area and ‘rural’ as living outside of an metropolitan statistical area.25

Table 1.

Categorical correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability among heterosexual men (n=296)

| No. willing to get HPV vaccine/total no. in category (n%) | Bivariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | |||

| 18–26 | 13/34 (38) | 1.17 (0.54 to 2.55) | – |

| 27–45 | 49/126 (39) | 1.21 (0.73 to 1.99) | – |

| 46–59 | 47/136 (35) | ref. | – |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 79/230 (34) | ref. | – |

| Other race/ethnicity | 30/66 (45) | 1.59 (0.91 to 2.78) | – |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced, widowed, separated, never married | 49/97 (51) | ref. | ref. |

| Living with partner or married | 60/199 (30) | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.70)** | 0.59 (0.31 to 1.12) |

| Parent of daughter aged 9–26 y† | |||

| No | 30/210 (38) | ref. | – |

| Yes | 29/86 (34) | 0.83 (0.49 to 1.40) | – |

| Education | |||

| No college degree | 76/197 (39) | ref. | – |

| College degree | 33/99 (33) | 0.80 (0.48 to 1.32) | – |

| Household income | |||

| <$60000 | 52/147 (35) | ref. | – |

| ≥$60000 | 57/149 (38) | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.82) | – |

| Employment status | |||

| Not currently employed | 18/58 (31) | ref. | – |

| Currently employed | 91/238 (38) | 1.38 (0.74 to 2.54) | – |

| Health insurance status | |||

| No | 18/52 (35) | ref. | – |

| Yes | 91/244 (37) | 1.12 (0.60 to 2.10) | – |

| Urbanicity | |||

| Rural | 12/54 (22) | ref. | ref. |

| Urban | 97/242 (40) | 2.34 (1.17 to 4.67)* | 3.63 (1.47 to 8.96)** |

| Geographic region | |||

| Midwest | 22/64 (34) | ref. | – |

| Northeast | 18/52 (35) | 1.01 (0.47 to 2.18) | – |

| South | 42/113 (37) | 1.13 (0.60 to 2.15) | – |

| West | 27/67 (40) | 1.29 (0.63 to 2.62) | – |

| HPV and HPV vaccine | |||

| Awareness and knowledge about HPV | |||

| Never heard of HPV prior to survey | 39/114 (34) | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.96)* | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.97)* |

| Heard of HPV, low knowledge | 41/125 (33) | 0.47 (0.25 to 0.89)* | 0.27 (0.11 to 0.64)** |

| Heard of HPV, high knowledge | 29/57 (51) | ref. | ref. |

| Heard of HPV vaccine prior to survey | |||

| No | 39/110 (35) | ref. | – |

| Yes | 70/186 (38) | 1.10 (0.67 to 1.79) | – |

| Family member or friend has gotten HPV vaccine | |||

| No | 99/268 (37) | ref. | – |

| Yes | 10/28 (36) | 0.95 (0.42 to 2.14) | – |

| Think doctor would recommend HPV vaccine | |||

| No | 19/110 (17) | ref. | ref. |

| Don’t know | 58/139 (42) | 3.43 (1.89 to 6.24)** | 2.67 (1.30 to 5.47)** |

| Yes | 32/47 (68) | 10.22 (4.65 to 22.46)** | 9.02 (3.45 to 23.60)** |

| Health and health behaviours | |||

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker | 71/221 (32) | ref. | ref. |

| Smoker | 38/75 (51) | 2.17 (1.27 to 3.70)** | 1.32 (0.67 to 2.60) |

| Hepatitis B vaccination history | |||

| No doses received/Don’t know | 78/225 (35) | ref. | – |

| At least one dose received | 31/71 (44) | 1.46 (0.85 to 2.52) | – |

| Age at first sexual intercourse (y) | |||

| <16 | 29/71 (41) | 1.25 (0.73 to 2.16) | – |

| ≥16 | 80/225 (36) | ref. | – |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | |||

| <5 | 35/123 (29) | ref. | ref. |

| ≥5 | 74/173 (43) | 1.88 (1.15 to 3.08)* | 1.45 (0.76 to 2.74) |

| Prior STI diagnosis (other than HIV) | |||

| No | 93/263 (35) | ref. | – |

| Yes | 16/33 (48) | 1.72 (0.83 to 3.56) | – |

The multivariate model included variables from tables 1 and 2 bivariately associated (p<0.05) with willingness to get HPV vaccine. The multivariate model did not include variables with dashes (−). History of HIV infection and prior diagnosis of cancer or lesions were not examined due to only one participant reporting a history of each.

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

Approved age range for HPV vaccine for females in the United States.

HPV, human papillomavirus; ref., referent group; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Data analysis

We excluded one man from all analyses who reported receiving HPV vaccine. We used logistic regression models to examine bivariate correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability. Statistically significant bivariate predictors (p<0.05) were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model. We analysed unweighted data using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc.). All statistical tests were two-tailed, using a critical α of 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

The sample included men from all four geographic regions of the United States and primarily from more urban areas (82%) (table 1). Most men were non-Hispanic white (78%), married or living with a partner (67%), did not have a college degree (67%), employed (80%), had health insurance (82%), non-smokers (75%) and had either not received or were unsure if they had received one or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine (76%). Some men (29%) had daughters in the approved age range for HPV vaccination among females. A majority of men reported they had not initiated sex before age 16 y(76%) and reported five or more lifetime sexual partners (58%). One participant each reported a history of HIV infection and a history of cancer (oral, anal or penile) or lesions (anal or penile). Few men reported a history of STIs other than HIV (11%).

HPV

Most men (61%) reported hearing of HPV prior to the survey, but HPV knowledge was low among those who had (mean number of correct responses 3.5 out of 9.0, SD=2.2). Overall, 39% of men were unaware of HPV and 42% were aware but had low knowledge scores. Most men knew that HPV is an STI (66%) and is a common infection (60%) (figure 1). However, less than half of participants (45%) knew that HPV causes health problems for males, with even fewer knowing HPV can cause genital warts (34%) or cancer (oral cancer 21%, penile cancer=17%, anal cancer 14%).

Men perceived HPV-related disease to be severe (mean=3.24, SD=0.73), but they also reported low levels of perceived knowledge about HPV-related disease (mean=1.51, SD=0.48), concern about getting HPV-related disease (mean=1.30, SD=0.44) and perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease (mean=1.89, SD=0.63).

HPV vaccine

Most men (63%) reported hearing of HPV vaccine prior to the survey. Almost half of participants (47%) were unsure if their doctor would recommend they get HPV vaccine, if licenced for males. Thirty-seven percent thought their doctor would not recommend they get HPV vaccine, while only 16% thought their doctor would recommend the vaccine. Participants reported moderate levels of perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (mean=2.65, SD=0.87) and barriers to getting HPV vaccine if it were available for males (mean=2.76, SD=0.87). Participants reported fairly high levels of anticipated regret if they did not get vaccinated and later got an HPV infection (mean=2.93, SD=1.05).

Eight men (3%) reported talking to a doctor previously about getting HPV vaccine for themselves and 9% reported a family member or friend had been vaccinated. One man reported trying to get HPV vaccine but could not since the doctor would not give the vaccine to males.

Thirty-seven percent (109/296) of men were willing to receive HPV vaccine. In bivariate analyses (tables 1 and 2), men were more willing to get the HPV vaccine if they were from urban areas, either thought or were unsure if their doctor would recommend HPV vaccine, were current smokers or reported five or more lifetime sexual partners (all p<0.05). Willingness was lower among men who were married or living with their partner and those who had either not heard of HPV prior to the survey or had heard of it but had low knowledge (all p<0.05). Men willing to get vaccinated also reported higher levels of concern about getting HPV-related disease, perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease, perceived effectiveness of HPV vaccine or anticipated regret if they did not get vaccinated and later became infected with HPV (all p<0.05). Acceptability was modest among younger men aged 18–26 y (38%) and did not differ across age groups (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Continuous correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability among heterosexual men (n=296)

| Mean (SD)

|

Bivariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not willing (n=187) | Willing (n=109) | |||

| Perceived knowledge of HPV-related disease | 1.50 (0.50) | 1.54 (0.46) | 1.19 (0.73 to 1.93) | – |

| Concern about getting HPV-related disease | 1.21 (0.38) | 1.45 (0.51) | 3.53 (1.93 to 6.46)** | 1.64 (0.79 to 3.41) |

| Perceived severity of HPV-related disease | 3.23 (0.75) | 3.27 (0.70) | 1.08 (0.78 to 1.50) | – |

| Perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease | 1.74 (0.61) | 2.15 (0.57) | 3.07 (2.00 to 4.71)** | 1.80 (1.02 to 3.17)* |

| Perceived barriers to getting HPV vaccine | 2.71 (0.89) | 2.86 (0.83) | 1.21 (0.92 to 1.59) | – |

| Perceived effectiveness of HPV vaccine | 2.43 (0.85) | 3.02 (0.78) | 2.37 (1.72 to 3.27)** | 1.86 (1.22 to 2.83)** |

| Anticipated regret if chose not to get vaccinated and later developed HPV infection | 2.62 (1.07) | 3.46 (0.78) | 2.54 (1.89 to 3.41)** | 2.01 (1.40 to 2.89)** |

The multivariate model included variables from tables 1 and 2 bivariately associated (p<0.05) with willingness to get HPV vaccine. The multivariate model did not include variables with dashes (−).

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

In multivariate analyses (tables 1 and 2), HPV vaccine acceptability was higher among men from urban areas (OR 3.63, 95% CI 1.47 to 8.96) or if they either thought (OR 9.02, 95% CI 3.45 to 23.60) or were unsure (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.30 to 5.47) if their doctor would recommend they get vaccinated. Men reporting higher levels of perceived likelihood of getting HPV-related disease (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.17), perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.83) or anticipated regret if they did not get vaccinated and an HPV infection later developed (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.89) were also more willing to get vaccinated. Compared to participants with high HPV knowledge, acceptability was lower among participants who had not heard of HPV (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.97) and those with low knowledge (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.64).

DISCUSSION

HPV infection is common in men1,2 and can lead to negative health outcomes for infected men and their sexual partners.4,6,7 However, nearly 40% of heterosexual men had not heard of HPV prior to the survey. Among those who had heard of HPV, knowledge about HPV infection was low as in previous research.18,26 These findings indicate men need more information about HPV and its potential health consequences.

Just over one-third of participants were willing to get HPV vaccine, similar to prior estimates among adult men (33%–48%).16,17 Numerous modifiable beliefs were correlated with vaccine acceptability, including perceived likelihood of HPV-related disease, perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness and anticipated regret. Participants’ thoughts regarding whether their doctor would recommend they get HPV vaccine was also a strong correlate. A prior study among heterosexual men also found that perceived likelihood was associated with HPV vaccine acceptability,27 while we previously found correlates of vaccine acceptability among gay and bisexual men included doctor’s recommendation, perceived vaccine effectiveness and anticipated regret.21

In contrast to other studies among men,18,28 we did not find a strong association between number of lifetime sexual partners and HPV vaccine acceptability. This may be attributable to most men (67%) being married or living with a partner. When we examined only men who were not married or living with a partner in exploratory analyses, number of lifetime sexual partners was not bivariately associated with vaccine acceptability (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.38; p=0.941). This suggests that heterosexual men with lower likelihood of previous HPV exposure may have similar levels of vaccine acceptability as men with higher levels of past sexual activity.

The population-level benefit of vaccinating adult men against HPV is currently not known. While the target group for HPV vaccination in males will likely be young adolescents (assuming vaccine licensure for males occurs), adult men will still have to decide whether ‘off-label’ vaccination offers enough individual benefit to pay out-of-pocket for the vaccine. Our findings are important because they provide early insight into factors that may affect these decisions. These same factors also offer potential targets for future efforts to increase informed HPV vaccination decision making among adult men, which may reduce inappropriate demand and use of the vaccine. While this sample consisted mostly of men outside the likely targeted age range for HPV vaccine in males, acceptability did not differ with age. Results may, therefore, also provide a starting point for future research among younger adolescent males.

We believe the strengths of this study are the use of a national sample, a high participation rate and examining many constructs from the HPV vaccine acceptability literature. While the study occurring before HPV vaccine licensure for males in the United States is a potential limitation, the study timing is also a strength because results provide early information on this important topic. HPV vaccine acceptability may overestimate behaviour if the vaccine is approved for males. Although our sample was drawn from a study panel known to closely resemble the United States population on many demographic features,29,30 most participants were non-Hispanic white and of high socioeconomic status.

Among a national sample of heterosexual men, we found low knowledge about HPV and moderate HPV vaccine acceptability. Multiple modifiable beliefs were associated with vaccine acceptability, providing insight into potentially important targets for future communication and education messages targeted towards males to increase informed decision-making regarding HPV vaccination. Additional research among males in the likely targeted age range for HPV vaccination is needed to confirm our findings.

Key messages.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men was moderate.

Men had low knowledge about HPV, particularly concerning diseases associated with persistent HPV infection.

Modifiable beliefs associated with vaccine acceptability provide potential targets for future efforts to increase informed decisions by men about HPV vaccination.

Acknowledgments

Funding American Cancer Society (MSRG-06-259-01-CPPB), the National Cancer Institute (R25 CA57726) and the Investigator-Initiated Studies Program of Merck & Co, Inc.

Footnotes

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina.

Contributors PLR performed the data analysis and wrote the initial manuscript draft. NTB conceived the study, supervised its implementation, provided guidance and assisted with the writing. JSS provided guidance for the data analysis and writing process. All authors helped to conceptualise ideas, interpret findings and review drafts of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests A research grant to Noel Brewer, PhD (PI) from Merck & Co., Inc. funded the study. Merck & Co., Inc. played no role in the study design, planning, implementation, analysis, or reporting of the findings. Jennifer S. Smith has received research grants, honoraria and consulting fees during the last four years from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and worked collaboratively on a research grant from Merck & Co., Inc.

References

- 1.Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among men: a systematic review of the literature. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1044–57. doi: 10.1086/507432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielson CM, Harris RB, Dunne EF, et al. Risk factors for anogenital human papillomavirus infection in men. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1137–45. doi: 10.1086/521632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano AR, Lu B, Nielson CM, et al. Age-specific prevalence, incidence, and duration of human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of 290 US men. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:827–35. doi: 10.1086/591095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):3036–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Ladner MB, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution and serological response to HPV type 6 virus-like particles in patients with genital warts. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2058–63. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2058-2063.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch FX, Castellsague X, Munoz N, et al. Male sexual behavior and human papillomavirus DNA: key risk factors for cervical cancer in Spain. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1060–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.15.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habel LA, Van Den Eeden SK, Sherman KJ, et al. Risk factors for incident and recurrent condylomata acuminata among women. A population-based study. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:285–92. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Drug Administration. Gardasil (quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18) Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck & Co; Product approval information–licensing action [package insert] http://www.fda.gov/cber/label/HPVmer060806LB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palefsky J, Giuliano A on behalf of the Male Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine Efficacy Trial Study Group. Efficacy of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV 6/11/16/18-related genital infection in young men. Abstract of presentation at the European Research Organization on Genital Infection and Neoplasia (EUROGIN) International Multidisciplinary Conference; Nice, France. November 2008; http://www.eurogin.com. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliano A, Palefsky J on behalf of the Male Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine Efficacy Trial Study Group. The efficacy of quadrivalent HPV (types 6/11/16/18) vaccine in reducing the incidence of HPV infection and HPV-related genital disease in young men. Abstract of presentation at the European Research Organization on Genital Infection and Neoplasia (EUROGIN) International Multidisciplinary Conference; Nice, France. November 2008; http://www.eurogin.com. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbasha EH, Dasbach EJ, Insinga RP. Model for assessing human papillomavirus vaccination strategies. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:28–41. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taira AV, Neukermans CP, Sanders GD. Evaluating human papillomavirus vaccination programs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1915–23. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner A. FDA panel backs giving HPV vaccine Gardasil to young males. 2009 Sep 11; http://abcnews.go.com/Health/Healthday/fda-panel-backs-giving-hpv-vaccine-gardasil-boys/story?id=8531585.

- 14.Hildesheim A, Herrero R. Human papillomavirus vaccine should be given before sexual debut for maximum benefit. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1431–2. doi: 10.1086/522869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain N, Euler GL, Shefer A, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) awareness and vaccination initiation among women in the United States, national immunization survey-adult 2007. Prev Med. 2009;48:426–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, et al. Men’s attitudes toward receiving the human papillomavirus vaccine. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008;12:276–81. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318167913e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenselink CH, Schmeink CE, Melchers WJ, et al. Young adults and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Public Health. 2008;122:1295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones M, Cook R. Intent to receive an HPV vaccine among university men and women and implications for vaccine administration. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57:23–32. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.1.23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert P, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, et al. HPV vaccine acceptability in heterosexual, gay, and bisexual men. Working Paper. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1557988310372802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiter PL, Brewer NT, McRee AL, et al. Acceptability of HPV vaccine among a national sample of gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:197–203. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf542c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazekas KI, Brewer NT, Smith JS. HPV vaccine acceptability in a rural southern area. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:539–48. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating KM, Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, et al. Potential barriers to HPV vaccine provision among medical practices in an area with high rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4 Suppl):S61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter PL, Brewer NT, McRee AL, et al. Parents’ health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Management and Budget. Standards for defining metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas; notice. Fed Regist. 2000;65:82227–38. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/fedreg/metroareas122700.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerend MA, Magloire ZF. Awareness, knowledge, and beliefs about human papillomavirus in a racially diverse sample of young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerend MA, Barley J. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among young adult men. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:58–62. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818606fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, et al. Variables associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptance by men. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:34–42. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Singer S, et al. Validity of the survey of health and internet and knowledge network’s panel and sampling. Updated 2003 http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/oct/pdf/04_0004_01.pdf.

- 30.Dennis JM. Description of within-panel survey sampling methodology: the knowledge networks approach. Updated 2009 http://www.knowlegenetworks.com/ganp/docs/KN%20Within-Panel%20Survey20Sampling%20Methodology.pdf.