Abstract

Pairing of homologous chromosome is a unique event in meiosis that is essential for both haploidization of the genome and genetic recombination. Rapid chromosome movements during meiotic prophase are a key feature of the pairing process. This is usually telomere-led, and in metazoans is dependent upon microtubules and dynein. Chromosome movements culminate in the formation of a meiotic “bouquet” in which nuclear envelope-associated telomeres are clustered at the centrosomal pole of the nucleus. Bouquet formation is thought to facilitate homolog pairing. Recent studies reveal that coupling of telomeres to cytoplasmic dynein is mediated by SUN1 in the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and KASH5 a novel protein of the outer nuclear membrane (ONM). Together SUN1 and KASH5 assemble to form a transluminal LINC (linker of the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) complex that spans both nuclear membranes. SUN1 forms attachment sites for telomeres at the INM while KASH5 functions as a dynein adaptor at the ONM. In mice deficient in KASH5, homologous chromosome pairing does not occur. The result is that meiosis is arrested at the leptotene/zygotene stage of meiotic prophase 1, and as a consequence both male and female mice are infertile. This study demonstrates an essential role for dynein directed telomere movement during meiotic prophase.

Keywords: nuclear envelope, meiosis, dynein, nuclear membrane, spermatocyte, LINC complex

Introduction

The evolution and diversification of eukaryotes has, to a large extent been facilitated by sexual reproduction. The mixing and subsequent shuffling of genes between generations provides the raw material upon which natural selection can act. Sexual life cycles are underpinned by the process of meiosis, in which parental homologous chromosomes are segregated, in a reduction division, to yield haploid cells. In higher eukaryotes, meiosis is a crucial step in the development of mature germ cells, and the evolution of meiosis has been a topic of considerable debate.1 While there is little doubt that meiosis represents a modified form of mitosis, it features several unique steps. These include the pairing of homologous chromosomes coupled with widespread recombination between non-sister chromatids. Following homolog segregation, a second mitosis-like division distributes non-replicated chromatids between daughter cells.

The first meiotic prophase (prophase 1) is characterized by the pairing of homologous chromosomes and the assembly of synaptonemal complexes.2-5 The latter are specialized structures resembling molecular zippers extending the entire length of each chromosome and which hold the homologs together. The mechanism by which homolog pairs are established during meiotic prophase has been a topic of debate lasting more than a century. One of the significant early observations was that during prophase 1 telomeres, in association with the nuclear envelope (NE), cluster at the nuclear pole closest to the centrosome, with the chromosomes adopting a transient bouquet-like configuration (references in Scherthan, 20016). It is now thought that the process of bouquet formation, which features rapid chromosome movements, might facilitate the mutual searching of the homologous chromosomes as a prelude to synapsis.6,7 Studies in a variety of organisms now suggest that this is very likely the case and that the NE, the barrier that separates the nucleus and cytoplasm, plays a central role in the pairing process. Significantly, the NE-associated chromosomal movements that are a prelude to bouquet formation are actually driven by the cytoskeleton, and in this way NE-linked chromosome dynamics are intimately tied to meiotic progression.7-10 The implication here is that there must be mechanisms to transmit cytoskeletal forces across the NE to individual chromosomes.

The general structure of the NE has been conserved in all eukaryotes.11,12 Its most prominent features are the inner and outer nuclear membranes (INM and ONM) separated by a peri-nuclear space (PNS) of about 50 nm. The two nuclear membranes are periodically connected at annular junctions where they are spanned by nuclear pore complexes, massive multi-protein assemblies mediating the to-and-fro movement of macromolecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm. However, despite these connections, the INM and ONM are biochemically distinct. The INM contains a unique array of 60 or more integral membrane proteins13 and is associated on its nuclear face with the nuclear lamina, a thin (10–50 nm) relatively insoluble protein meshwork. The nuclear lamina is composed primarily of A- and B-type lamins,14 prototype members of the intermediate filament protein family. In addition to its interactions with the INM, which is mediated by several integral proteins, the lamina provides anchoring sites at the nuclear periphery for underlying chromatin domains and is thought to represent an important structural determinant for the NE as a whole. The ONM, on the other hand, is functionally related to the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER), with which it maintains numerous connections. In this way, the ER, ONM, and INM may be considered as separate domains within a single continuous membrane system with the PNS representing a perinuclear extension of the ER lumen.

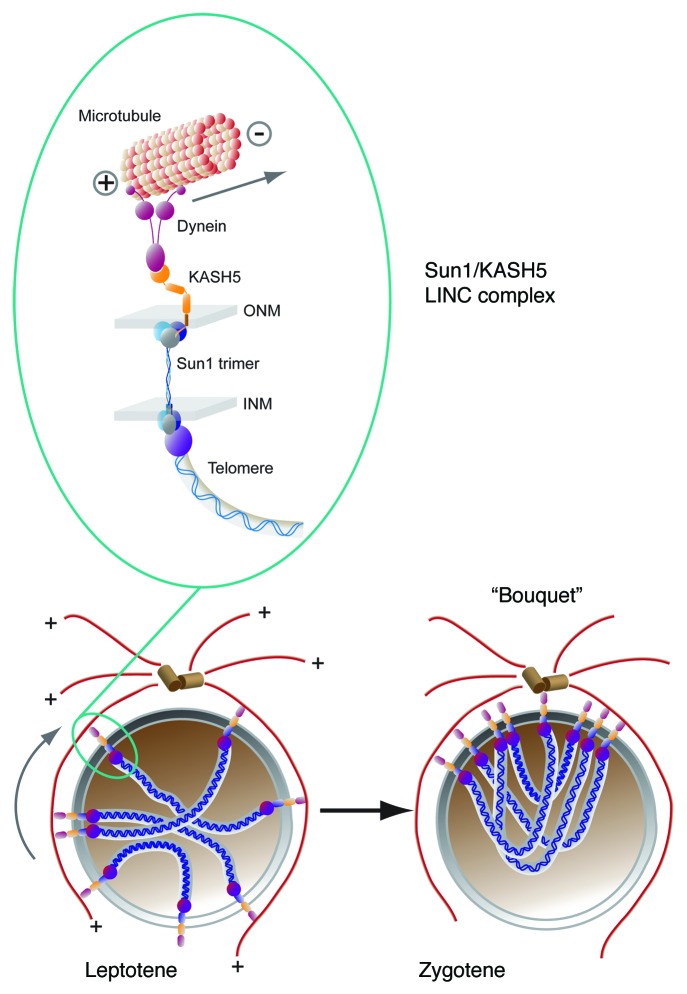

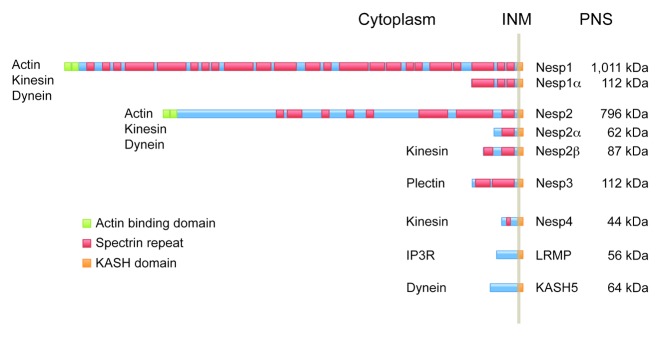

LINC Complexes and Nucleocytoplasmic Coupling

The double membrane architecture of the NE raises the question of how chromosomal regions, telomeres in particular, can be physically linked to the cytoskeleton during meiotic prophase 1. Since the NE remains intact during the process of synapsis there has to be molecular machinery in place that spans both the INM and ONM that can interact with cytoskeletal components and with chromatin. A possible solution to this puzzle was provided by studies on interphase somatic cells. These revealed that nuclear structures, including nuclear lamins, are mechanically coupled to a variety of cytoskeletal proteins.15 The nature of this coupling is partly dependent on two families of integral nuclear membrane proteins: SUN (Sad1, Unc-84) domain proteins, which reside in the INM, and KASH (Klarsicht, ANC-1, Syne Homology) domain proteins, residing in the ONM.16,17 KASH domain proteins play important roles in nuclear migration and positioning in a variety of cell and tissue types in multiple organisms, and interact with an assortment of cytoskeletal components. For instance, both Nesprins 1 (Nesp1) and 2 (Nesp2) in mammals bind F-actin as does ANC-1 in C. elegans.18-22 Drosophila Klarsicht and C. elegans ZYG-12 both function as ONM adaptors for cytoplasmic dynein,23,24 while mammalian Nesprin 4 (Nesp4) represents an epithelial-specific ONM binding partner for conventional Kinesin-1.25,26 Dynein and kinesin binding sites are also present in Nesp1 and Nesp2. Finally, mammalian Nesprin 3 (Nesp3) interacts with plectin, a versatile cytolinker molecule, that provides a connection to the intermediate filament system.27-29 In this way, diverse ONM KASH domain proteins are able to mediate associations between the NE and all three branches of the cytoskeleton. An overview of the mammalian KASH protein family is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Comparison of mammalian KASH-domain proteins.25,29,59,60,64,65 In all cases the N-terminal domain resides within the cytoplasm while the C-terminal KASH domain extends across the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and into the peri-nuclear space (PNS) where it interacts directly with members of the SUN domain protein family. The largest isoforms of nesprins 1 and 2 (Nesp1 and Nesp2) feature an N-terminal actin binding domain. These proteins also possess kinesin and dynein binding functions. In the case of Nesp2, the kinesin binding region resides close to the KASH domain since a smaller Nesp2 isoform, Nesp2β, is capable of recruiting kinesin to the nuclear envelope.66 One other vertebrate KASH domain protein, Nesp4 also functions in kinesin binding. Nesp4 is expressed largely in epithelial cells where it might have a role in nuclear positioning. Nesp3 functions as an adaptor for plectin, a versatile cytolinker molecule that provides a means of coupling nuclei to the intermediate filament system. Lymphocyte restricted membrane protein (LRMP/Jaw1) is unusual in that it doesn’t appear to interact with cytoskeletal components. Instead LRMP forms an association with the IP3 receptor (IP3R).67 The final member of the KASH protein family, KASH5, functions as an ONM adaptor for cytoplasmic dynein in meiotic cells.

Since the nuclear membranes share numerous continuities with the peripheral ER, the question arises as to how KASH proteins are retained and concentrated within the ONM. The answer is provided by the eponymous KASH domain and its interactions. The KASH domain is a C-terminal sequence of some 50–60 amino acid residues.22 It features a single membrane-spanning region followed by a short sequence of 40 residues or less that extends in to the PNS. The KASH domain is both necessary and sufficient for targeting to the ONM. In C. elegans retention of the KASH domain protein, ANC-1, within the ONM is dependent upon the presence in the INM of UNC-84,22 a prototype SUN domain protein.

Both mouse and human genomes encode at least six SUN domain proteins, SUN1, 2, 3, 4 (SPAG4), 5 (SPAG4L), and osteopotentia.30,31 Of these, only two, SUN1 and SUN2, are widely expressed. Both SUN1 and SUN2 (as well as SUN3–5) are type II membrane proteins. The SUN1 and SUN2 N-terminal domains (~200–400 residues) are exposed to the nucleoplasm where they may interact with a variety of nuclear components,32-35 including members of the lamin family. The C-terminal region of SUN1 and SUN2 extends into the PNS. A membrane proximal sequence, which forms a triple helical coiled-coil30,32-35 terminates in the globular SUN domain. It is now clear from studies in both mammals and C. elegans that SUN and KASH domains directly interact. In this way INM SUN domain proteins provide a unique function as transluminal tethers for ONM KASH proteins.34-37 The implication of these findings is that together, SUN and KASH domain proteins form a pair of links in a molecular chain spanning both nuclear membranes that physically couples nuclear components to the cytoskeleton. These SUN-KASH pairs are termed LINC complexes (for linker of the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton).35

Recent structural studies reveal that in mammalian SUN2, the SUN domain functions as a homo-trimer.38,39 KASH-domain binding involves extended interactions at the interface between two adjacent SUN domains.38 This association may be stabilized by the formation of an interchain disulphide bond between a cysteine within the KASH domain and an adjacent SUN domain cysteine. SUN2 (and in all likelihood, SUN1) trimerization is mediated by the membrane proximal luminal coiled-coil domain. This domain has a predicted length of 40–50 nm, sufficient to span the PNS and to bring the trimeric SUN domains close to the ONM where they can bind KASH sequences. The molecular modeling indicates that each SUN protein trimer has the capacity to bind three KASH domains. Accordingly, if individual KASH proteins are able to oligomerize, then SUN-KASH associations could promote the formation of extensive LINC complex arrays within the NE.

A number of LINC complex isoforms, defined by their SUN/KASH constituents, possess essential roles in nuclear movement and positioning in a variety of cell and tissue types. Actin-dependent nuclear repositioning during fibroblast migration40 is dependent on Nesp1/2-containing LINC complexes. Cell cycle-dependent nuclear oscillation during neuronal and retinal differentiation utilizes LINC complexes that function as adaptors for microtubule motor proteins.41 A Nesp4-containing LINC complex is required for the microtubule- and Kinesin-1-dependent basal positioning of the nucleus in outer hair cells (OHCs) of the inner ear.25,26 In the absence of Nesp4 OHC viability is severely compromised resulting in progressive irreversible hearing loss.26 Dynein-binding LINC complexes are also employed in pronuclear migration in fertilized eggs.24,42 In addition to these roles in directed nuclear movement and anchoring, it is now clear that SUN and KASH domain proteins may also influence intranuclear organization. During meiosis, LINC complexes have a critical role in transmitting cytoskeletal forces across both nuclear membranes to individual chromosomes.43-46 LINC complexes therefore mediate the rapid chromosome movements that are a prelude to bouquet formation during meiotic prophase 1.6,47

LINC Complexes in Meiosis

Studies in both fission yeast and in C. elegans and have uncovered key roles played by LINC complexes during meiotic prophase. In S. pombe, the KASH protein Kms1 serves as an ONM adaptor for cytoplasmic dynein. Kms1 is anchored at the nuclear surface through transluminal association with Sad1, a SUN domain protein of the INM.48,49 Sad1 foci in turn constitute NE attachment sites for meiotic telomeres. The association between Sad1 and telomeres is mediated by both Taz-1 and Rap-1, a pair of telomeric proteins, as well as by the meiosis-specific proteins, Bqt-1, 2, 3, and 4.43,50 Through this chain of interactions spanning the NE, Kms1-associated dynein drives the clustering of telomeres to form a meiotic bouquet, as well as the subsequent “horsetail”-like nuclear movements that are thought to facilitate homologous chromosome pairing. Budding yeast also utilizes LINC complexes to mediate bouquet formation.9,51,52 However, it is unusual in that the process is actin-rather than microtubule-mediated.8,10

Meiosis in C. elegans follows the S. pombe archetype where homolog pairing is facilitated by dynein-dependent bouquet formation. In the nematode, however, association of chromosomes with the NE is not mediated by telomeres. Instead, chromosome specific pairing centers (PCs) are used. ZYG-12, a KASH domain protein of the ONM and functional homolog of Kms1 functions as an adaptor for cytoplasmic dynein. An INM SUN domain protein, SUN-1/matefin (MTF-1), tethers ZYG-12 in the ONM and at the same time defines attachment sites for chromosomal PCs.46,53,54 This association between SUN-1/MTF-1 and PCs, is mediated by soluble chromosome- and PC-specific proteins (ZIM-1, -2, -3, and HIM-8).46,53,55-57

LINC complexes are also implicated in mammalian meiotic progression. Gene knockout studies in mice revealed that the INM SUN domain protein, SUN1, is essential for gametogenesis.44,45 Both males and females deficient in SUN1 are infertile. Infertility in males is clearly due to the arrest of primary spermatocytes in meiotic prophase 1, with the complete failure of telomeres to localize appropriately to the nuclear periphery. These studies demonstrate that, as with fission yeast, telomere association with the NE is a prerequisite for bouquet formation and efficient homolog pairing. Telomere clustering always occurs at the pole of the nucleus that is closest to the centrosome or microtubule organizing center (MTOC, reviewed in ref. 6 and 58). By analogy with S. pombe and C. elegans, this is likely to be a dynein-mediated process requiring the function of a meiotic LINC complex that couples telomeres to the microtubule system. While SUN1 clearly represents the INM portion of such a LINC complex, the identity of its ONM KASH domain portion has until very recently remained uncertain.

KASH5: A New Dynein Adaptor

A candidate KASH component of a meiotic LINC complex, KASH5, was first revealed in a yeast two-hybrid screen of a mammalian testis library using the mouse cohesin protector protein, shugosin 2, as bait.59 Although this interaction was likely an artifact, characterization of KASH5 revealed localization to the NE of primary spermatocytes in a SUN1-dependent manner. Furthermore it was found to associate with p150Glued, a component of the dynein regulatory complex, dynactin. In complementary studies, we had searched for new proteins that displayed sequence homology with the Nesp2 KASH domain.25 We were able to identify two additional KASH domain proteins, Nesp425 and lymphocyte restricted membrane protein (LRMP, also known as JAW1).60 Both of these proteins display SUN1/2- and KASH domain-dependent localization to the ONM. In the case of Nesp4, we now know that it functions as an epithelial NE adaptor for Kinesin-1.25 A second homology search using the complete LRMP sequence as probe detected a zebrafish KASH protein, Futile Cycle (Fue). Fue is required for dynein-dependent nuclear migration in zebrafish zygotes.42,61 When aligned with mouse LRMP, Fue displays an N-terminal extension that contains its dynein-binding region. Yet a third homology search using the unique Fue sequence revealed mouse KASH5. Further in silico analysis of the complete KASH5 sequence of 578 amino acid residues highlighted a degenerate, but nevertheless recognizable C-terminal KASH domain, a central predicted coiled-coil and an N-terminal domain containing a calmodulin-like EF-hand sequence.62

Consistent with the observations of Morimoto et al. (2012),59 we confirmed that in adult mice, KASH5 expression was restricted largely to the testis.60 However, RT-PCR also detected the presence of KASH5 transcripts in bone marrow derived cells. Although no cell lines could be found that expressed KASH5 at any level, when recombinant KASH5 was introduced in to HeLa or HEK293T cells it localized to the ONM.60 This localization was dependent upon the integrity of its KASH domain as well as upon the presence of SUN1 or SUN2. Significantly, KASH5 was able to recruit cytoplasmic dynein and associated regulatory molecules (e.g., the dynactin complex and LIS1) to the NE. Recruitment depended on the KASH5 N-terminal domain containing the EF-hand motif. Related experiments, in cultured cells, revealed that KASH5 can self-associate through the central coiled-coil domain. Taken together, these findings indicate that KASH5 defines a new LINC complex species that couples the NE and associated nuclear structures to the microtubule system via cytoplasmic dynein. The fact that KASH5 can oligomerize also suggests that KASH5 LINC complexes could potentially form large arrays or clusters.

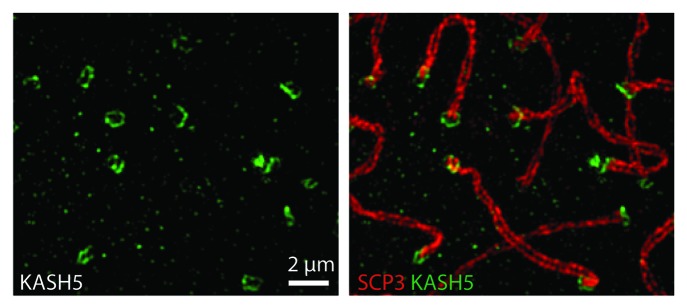

SUN1 is the predominant SUN domain protein expressed in spermatocytes.44 By conventional immunofluorescence microscopy it appears to be distributed across the spermatocyte nuclear surface as discrete foci.44 Each of these foci is coincident with a telomere attachment site. Furthermore, SUN1 and KASH5 precisely co-localize, consistent with the notion that these two molecules assemble to form a meiotic LINC complex.60 Such a suggestion is reinforced by the finding that KASH5 is lost from the spermatocyte NE in mice deficient in SUN1.59,60

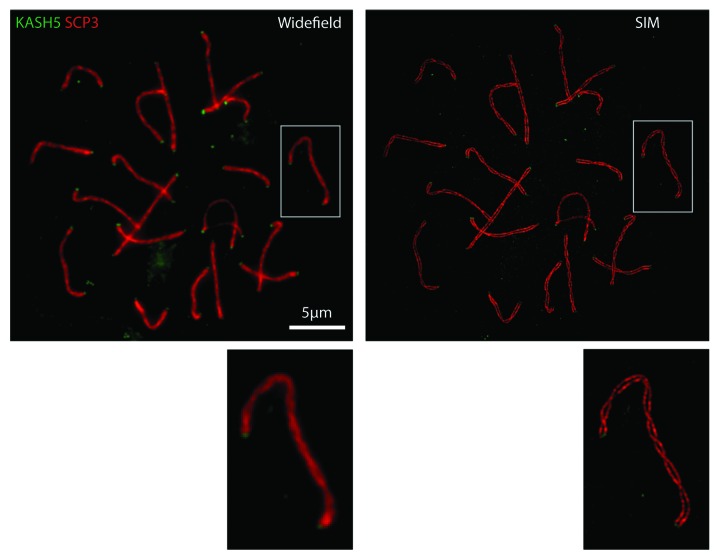

To better define the physiological role of KASH5 we derived mice in which both KASH5 alleles were non-functional.60 While KASH5-null mice are healthy with an apparently normal lifespan, both males and females are infertile. In the males no mature sperm cells are produced whatsoever. A more careful analysis reveals that spermatogenesis is arrested during meiotic prophase 1. Arrest was at pre-pachytene and was associated with a failure to resolve double strand DNA breaks. Loss of maturing sperm coincided with extensive apoptosis (as measured by TUNEL staining) in the seminiferous tubules. If as we suspected that KASH5-containing LINC complexes are required for telomere clustering and efficient homolog pairing then prophase arrest should be occurring prior to synaptonemal complex formation. SCs contain two major structural features. Axial elements assemble as a strip along the entire length of each homolog. During the final stages of SC formation axial elements become linked by a series of transverse elements akin to the rungs of a ladder. By following the recruitment and assembly of the axial element protein SCP3 and the transverse element protein SCP1 it is possible to follow the progress of synapsis. This analysis was greatly facilitated by the use of structured illumination microscopy (SIM),63 a super-resolution technique that allowed us to resolve paired axial elements, which in synapsed chromosomes, are separated by a distance of only 100–150 nm (Fig. 2). Visualization of individual axial elements within assembled SCs is not possible using conventional light microscopy which has a diffraction limited resolution of about 200 nm (Fig. 2). These analyses revealed that in the absence of KASH5 homologous chromosomes remained unpaired. Nevertheless, SUN1 was still localized appropriately as discreet foci in the KASH5-null spermatocytes and was still capable of mediating telomere attachment to the NE. However, in the absence of KASH5, these telomeres had lost their link to dynein and to the microtubule system and therefore failed to cluster at the centrosomal pole of the nucleus. The prediction was that telomere led chromosome movements during prophase 1 should be significantly curtailed in KASH5-null spermatocytes.

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence microscopy of a wild type spermatocyte spread employing antibodies against KASH5 (green) and SCP3 (red), an axial element component of synaptonemal complexes. Individual axial elements are not resolved using conventional widefield microscopy. However, these structures can be distinguished using structured illumination microscopy (SIM).

SIM also revealed some subtle features of SUN1/KASH5 LINC complexes that were not evident with conventional light microscopy. At unpaired telomere attachment sites, the LINC complexes, visualized using either anti-SUN1 or anti-KASH5 antibodies, appeared in ring-like clusters. Following homolog pairing, rings merged in to figure-of-eight arrangements (Fig. 3). However, in KASH5-null spermatocytes, while SUN1 was still clustered to form telomere attachment sites, the ring-like organization of these clusters was lost. Although SUN1 functions as a tether for KASH5, the nanoscale distribution of SUN1 appears to be influenced by KASH5.60

Figure 3. Structured illumination microscopy of spematocytes labeled with antibodies against KASH5 and SCP3. KASH5 is organized into ring or figure-eight-like structures.

From these results it appears that mammalian meiosis conforms to the paradigm established in S. pombe and C. elegans whereby a LINC complex couples telomeres (or PCs in the case of C. elegans) within the prophase nucleus to dynein within the cytoplasm (Fig. 4). By this route, meiotic LINC complexes promote telomere/PC clustering leading to homologous chromosome pairing (Fig. 4). It follows therefore, that KASH5 represents a functional homolog of S. pombe Kms1 and C. elegans ZYG-12. From a purely practical point of view our work has focused primarily on spermatogenesis. However, given that female KASH5-null mice are also infertile and have ovaries that are devoid of follicles, it is highly likely that KASH5 has a similar role in oogenesis.60

Figure 4. A SUN1/KASH5 LINC complex that spans both the inner and outer nuclear membranes (INM and ONM) couples telomeres to cytoplasmic dynein, a microtubule motor protein. During the transition from leptotene to zygotene stages of meiotic prophase 1, the minus end directed motor activity of dynein will lead to clustering of telomeres (“bouquet” formation) at the nuclear pole adjacent to the centrosome.

Unanswered Questions

There are still a number of issues to be addressed concerning the function of meiotic LINC complexes in mammals. While it is clear that SUN1 defines NE attachment sites for telomeres the nature of the interaction and its regulation remain unknown. Whether the association between SUN1 and telomeres or sheltrin complex components is direct or whether there might be other meiosis-specific molecules involved that are similar in function to Bqt1–4 in S. pombe remains unknown.43,50 Both zebrafish Fue and C. elegans ZYG-12 have essential roles in pronuclear migration in early embryos.24,42,61 This activity is linked to the recruitment of dynein to the NE. This obviously raises the possibility that KASH5 might have a similar role following fertilization in mammals. Further studies using conditional mouse strains are being pursued to test this hypothesis as well as to explore the role of KASH5 in female germ cell development.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/27819

References

- 1.Wilkins AS, Holliday R. The evolution of meiosis from mitosis. Genetics. 2009;181:3–12. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.099762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraune J, Schramm S, Alsheimer M, Benavente R. The mammalian synaptonemal complex: protein components, assembly and role in meiotic recombination. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revenkova E, Jessberger R. Shaping meiotic prophase chromosomes: cohesins and synaptonemal complex proteins. Chromosoma. 2006;115:235–40. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallente RU, Cheng EY, Hassold TJ. The synaptonemal complex and meiotic recombination in humans: new approaches to old questions. Chromosoma. 2006;115:241–9. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zickler D. From early homologue recognition to synaptonemal complex formation. Chromosoma. 2006;115:158–74. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherthan H. A bouquet makes ends meet. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:621–7. doi: 10.1038/35085086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CY, Conrad MN, Dresser ME. Meiotic chromosome pairing is promoted by telomere-led chromosome movements independent of bouquet formation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trelles-Sticken E, Adelfalk C, Loidl J, Scherthan H. Meiotic telomere clustering requires actin for its formation and cohesin for its resolution. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:213–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad MN, Lee CY, Chao G, Shinohara M, Kosaka H, Shinohara A, Conchello JA, Dresser ME. Rapid telomere movement in meiotic prophase is promoted by NDJ1, MPS3, and CSM4 and is modulated by recombination. Cell. 2008;133:1175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koszul R, Kim KP, Prentiss M, Kleckner N, Kameoka S. Meiotic chromosomes move by linkage to dynamic actin cables with transduction of force through the nuclear envelope. Cell. 2008;133:1188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson KL, Dawson SC. Evolution: functional evolution of nuclear structure. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:171–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart CL, Roux KJ, Burke B. Blurring the boundary: the nuclear envelope extends its reach. Science. 2007;318:1408–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1142034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schirmer EC, Florens L, Guan T, Yates JR, 3rd, Gerace L. Nuclear membrane proteins with potential disease links found by subtractive proteomics. Science. 2003;301:1380–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1088176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke B, Roux KJ. Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location. Dev Cell. 2009;17:587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starr DA, Han M. ANChors away: an actin based mechanism of nuclear positioning. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:211–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starr DA. A nuclear-envelope bridge positions nuclei and moves chromosomes. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:577–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Ragnauth C, Greener MJ, Shanahan CM, Roberts RG. The nesprins are giant actin-binding proteins, orthologous to Drosophila melanogaster muscle protein MSP-300. Genomics. 2002;80:473–81. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Xu R, Zhu B, Yang X, Ding X, Duan S, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Han M. Syne-1 and Syne-2 play crucial roles in myonuclear anchorage and motor neuron innervation. Development. 2007;134:901–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.02783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhen YY, Libotte T, Munck M, Noegel AA, Korenbaum E. NUANCE, a giant protein connecting the nucleus and actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3207–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padmakumar VC, Abraham S, Braune S, Noegel AA, Tunggal B, Karakesisoglou I, Korenbaum E. Enaptin, a giant actin-binding protein, is an element of the nuclear membrane and the actin cytoskeleton. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:330–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starr DA, Han M. Role of ANC-1 in tethering nuclei to the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 2002;298:406–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1075119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosley-Bishop KL, Li Q, Patterson L, Fischer JA. Molecular analysis of the klarsicht gene and its role in nuclear migration within differentiating cells of the Drosophila eye. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1211–20. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malone CJ, Misner L, Le Bot N, Tsai MC, Campbell JM, Ahringer J, White JG. The C. elegans hook protein, ZYG-12, mediates the essential attachment between the centrosome and nucleus. Cell. 2003;115:825–36. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roux KJ, Crisp ML, Liu Q, Kim D, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, Burke B. Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808602106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horn HF, Brownstein Z, Lenz DR, Shivatzki S, Dror AA, Dagan-Rosenfeld O, Friedman LM, Roux KJ, Kozlov S, Jeang KT, et al. The LINC complex is essential for hearing. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:740–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI66911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ketema M, Kreft M, Secades P, Janssen H, Sonnenberg A. Nesprin-3 connects plectin and vimentin to the nuclear envelope of Sertoli cells but is not required for Sertoli cell function in spermatogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:2454–66. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-02-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ketema M, Wilhelmsen K, Kuikman I, Janssen H, Hodzic D, Sonnenberg A. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3384–94. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Kuikman I, Tshimbalanga N, Janssen H, van den Bout I, Raymond K, Sonnenberg A. Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:799–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Q, Pante N, Misteli T, Elsagga M, Crisp M, Hodzic D, Burke B, Roux KJ. Functional association of Sun1 with nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:785–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohaskey ML, Jiang Y, Zhao JJ, Mohr A, Roemer F, Harland RM. Osteopotentia regulates osteoblast maturation, bone formation, and skeletal integrity in mice. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:511–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodzic DM, Yeater DB, Bengtsson L, Otto H, Stahl PD. Sun2 is a novel mammalian inner nuclear membrane protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25805–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasan S, Güttinger S, Mühlhäusser P, Anderegg F, Bürgler S, Kutay U. Nuclear envelope localization of human UNC84A does not require nuclear lamins. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haque F, Lloyd DJ, Smallwood DT, Dent CL, Shanahan CM, Fry AM, Trembath RC, Shackleton S. SUN1 interacts with nuclear lamin A and cytoplasmic nesprins to provide a physical connection between the nuclear lamina and the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3738–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3738-3751.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, Rattner JB, Shanahan C, Burke B, Stahl PD, Hodzic D. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padmakumar VC, Libotte T, Lu W, Zaim H, Abraham S, Noegel AA, Gotzmann J, Foisner R, Karakesisoglou I. The inner nuclear membrane protein Sun1 mediates the anchorage of Nesprin-2 to the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3419–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGee MD, Rillo R, Anderson AS, Starr DA. UNC-83 IS a KASH protein required for nuclear migration and is recruited to the outer nuclear membrane by a physical interaction with the SUN protein UNC-84. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1790–801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1035–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Z, Du X, Cai Z, Song X, Zhang H, Mizuno T, Suzuki E, Yee MR, Berezov A, Murali R, et al. Structure of Sad1-UNC84 homology (SUN) domain defines features of molecular bridge in nuclear envelope. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5317–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luxton GW, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Vintinner E, Gundersen GG. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 2010;329:956–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1189072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Lei K, Yuan X, Wu X, Zhuang Y, Xu T, Xu R, Han M. SUN1/2 and Syne/Nesprin-1/2 complexes connect centrosome to the nucleus during neurogenesis and neuronal migration in mice. Neuron. 2009;64:173–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindeman RE, Pelegri F. Localized products of futile cycle/lrmp promote centrosome-nucleus attachment in the zebrafish zygote. Curr Biol. 2012;22:843–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chikashige Y, Tsutsumi C, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Meiotic proteins bqt1 and bqt2 tether telomeres to form the bouquet arrangement of chromosomes. Cell. 2006;125:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding X, Xu R, Yu J, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Han M. SUN1 is required for telomere attachment to nuclear envelope and gametogenesis in mice. Dev Cell. 2007;12:863–72. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chi YH, Cheng LI, Myers T, Ward JM, Williams E, Su Q, Faucette L, Wang JY, Jeang KT. Requirement for Sun1 in the expression of meiotic reproductive genes and piRNA. Development. 2009;136:965–73. doi: 10.1242/dev.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato A, Isaac B, Phillips CM, Rillo R, Carlton PM, Wynne DJ, Kasad RA, Dernburg AF. Cytoskeletal forces span the nuclear envelope to coordinate meiotic chromosome pairing and synapsis. Cell. 2009;139:907–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hiraoka Y, Dernburg AF. The SUN rises on meiotic chromosome dynamics. Dev Cell. 2009;17:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miki F, Kurabayashi A, Tange Y, Okazaki K, Shimanuki M, Niwa O. Two-hybrid search for proteins that interact with Sad1 and Kms1, two membrane-bound components of the spindle pole body in fission yeast. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;270:449–61. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miki F, Okazaki K, Shimanuki M, Yamamoto A, Hiraoka Y, Niwa O. The 14-kDa dynein light chain-family protein Dlc1 is required for regular oscillatory nuclear movement and efficient recombination during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:930–46. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chikashige Y, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Tsutsumi C, Kojidani T, Sato M, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Membrane proteins Bqt3 and -4 anchor telomeres to the nuclear envelope to ensure chromosomal bouquet formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:413–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaspersen SL, Giddings TH, Jr., Winey M. Mps3p is a novel component of the yeast spindle pole body that interacts with the yeast centrin homologue Cdc31p. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:945–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conrad MN, Lee CY, Wilkerson JL, Dresser ME. MPS3 mediates meiotic bouquet formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8863–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606165104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Penkner A, Tang L, Novatchkova M, Ladurner M, Fridkin A, Gruenbaum Y, Schweizer D, Loidl J, Jantsch V. The nuclear envelope protein Matefin/SUN-1 is required for homologous pairing in C. elegans meiosis. Dev Cell. 2007;12:873–85. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penkner AM, Fridkin A, Gloggnitzer J, Baudrimont A, Machacek T, Woglar A, Csaszar E, Pasierbek P, Ammerer G, Gruenbaum Y, et al. Meiotic chromosome homology search involves modifications of the nuclear envelope protein Matefin/SUN-1. Cell. 2009;139:920–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips CM, Dernburg AF. A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2006;11:817–29. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips CM, Wong C, Bhalla N, Carlton PM, Weiser P, Meneely PM, Dernburg AF. HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell. 2005;123:1051–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baudrimont A, Penkner A, Woglar A, Machacek T, Wegrostek C, Gloggnitzer J, Fridkin A, Klein F, Gruenbaum Y, Pasierbek P, et al. Leptotene/zygotene chromosome movement via the SUN/KASH protein bridge in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harper L, Golubovskaya I, Cande WZ. A bouquet of chromosomes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4025–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morimoto A, Shibuya H, Zhu X, Kim J, Ishiguro K, Han M, Watanabe Y. A conserved KASH domain protein associates with telomeres, SUN1, and dynactin during mammalian meiosis. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:165–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201204085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horn HF, Kim DI, Wright GD, Wong ES, Stewart CL, Burke B, Roux KJ. A mammalian KASH domain protein coupling meiotic chromosomes to the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:1023–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dekens MP, Pelegri FJ, Maischein HM, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The maternal-effect gene futile cycle is essential for pronuclear congression and mitotic spindle assembly in the zebrafish zygote. Development. 2003;130:3907–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.00606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kretsinger RH, Barry CD. The predicted structure of the calcium-binding component of troponin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;405:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schermelleh L, Carlton PM, Haase S, Shao L, Winoto L, Kner P, Burke B, Cardoso MC, Agard DA, Gustafsson MG, et al. Subdiffraction multicolor imaging of the nuclear periphery with 3D structured illumination microscopy. Science. 2008;320:1332–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1156947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Q, Skepper JN, Yang F, Davies JD, Hegyi L, Roberts RG, Weissberg PL, Ellis JA, Shanahan CM. Nesprins: a novel family of spectrin-repeat-containing proteins that localize to the nuclear membrane in multiple tissues. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4485–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Behrens TW, Jagadeesh J, Scherle P, Kearns G, Yewdell J, Staudt LM. Jaw1, A lymphoid-restricted membrane protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Immunol. 1994;153:682–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneider M, Lu W, Neumann S, Brachner A, Gotzmann J, Noegel AA, Karakesisoglou I. Molecular mechanisms of centrosome and cytoskeleton anchorage at the nuclear envelope. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1593–610. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0535-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shindo Y, Kim MR, Miura H, Yuuki T, Kanda T, Hino A, Kusakabe Y. Lrmp/Jaw1 is expressed in sweet, bitter, and umami receptor-expressing cells. Chem Senses. 2010;35:171–7. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjp097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]