Abstract

Background

Entrainment, the change or elimination of tremor as patients perform a voluntary rhythmical movement by the unaffected limb, is a key diagnostic hallmark of psychogenic tremor.

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility of using entrainment as a bedside therapeutic strategy (‘retrainment’) in patients with psychogenic tremor.

Methods

Ten patients with psychogenic tremor (5 women, mean age, 53.6 ± 12.8 years; mean disease duration 4.3 ± 2.7 years) were asked to participate in a pilot proof-of-concept study aimed at “retraining” their tremor frequency. Retrainment was facilitated by tactile and auditory external cueing and real-time visual feedback on a computer screen. The primary outcome measure was the Tremor subscale of the Rating Scale for Psychogenic Movement Disorders.

Results

Tremor improved from 22.2 ± 13.39 to 4.3 ± 5.51 (p = 0.0019) at the end of retrainment. The benefits were maintained for at least 1 week and up to 6 months in 6 patients, with relapses occurring in 4 patients between 2 weeks and 6 months. Three subjects achieved tremor freedom.

Conclusions

Tremor retrainment may be an effective short-term treatment strategy in psychogenic tremor. Although blinded evaluations are not feasible, future studies should examine the long-term benefits of tremor retrainment as adjunctive to psychotherapy or specialized physical therapy.

Keywords: Psychogenic movement disorders, psychogenic tremor, entrainment

1. Introduction

Psychogenic tremor (PsyT) is the most common psychogenic movement disorder. It may be prolonged and disabling and there are no readily available therapies. PsyT varies in amplitude and distribution. Frequency variability is particularly important for diagnosis, especially if tremor completely stops (suppressibility) or entrains in frequency (entrainment or entrainability) to externally cued rhythmical movements of an unaffected body part [1]. Tremor entrainment and suppressibility, with or without the inability to copy simple cued movements with an unaffected body part, are hallmark clinical features of PsyT. Tremor entrainment not only helps define the clinically definite category of diagnostic certainty for PsyT but may also assist the diagnostic debriefing process at the bedside. We hypothesized that it might also be harnessed as a primary or adjunctive biofeedback treatment (‘retrainment’). In this manner, teaching tremor retrainment to patients may help in facilitating selfmodulation of the frequency and severity of their tremor, opening the possibility of eventual volitional control over their movements. In this proof-of-concept study, we sought to ascertain the feasibility of tremor retrainment as a biofeedback intervention for patients with chronic PsyT.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. System

A modified version of the Crescendo system (Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, Cleveland, Ohio) (Supplementary Figure 1A), originally designed for upper extremity motor rehabilitation, was used to apply an external sensory and visual feedback for rate retrainment. The system included inputs for measuring joint angles (electrogoniometers) and outputs for providing functional electrical stimulation (FES). One electrogoniometer was used to measure wrist flexion-extension and one channel of FES was applied to the wrist extensor muscles at a magnitude sufficient to produce a tactile sensation, but below the motor threshold to prevent elicitation of a muscle contraction. A LabVIEW interface was developed for controlling stimulation parameters, processing tremor kinematics, displaying feedback, and saving data (Supplementary Figures 1B and 2).

2.2. Participants and assessments

Ten patients with chronic PsyT were studied (5 women, mean age, 53.6 ± 12.8 years; mean disease duration 4.3 ± 2.7 years) were evaluated as necessary from 1–3 consecutive days (Table 1). All patients were recruited at the University of Cincinnati movement disorders center. The diagnosis of PsyT was made by documenting variability of hand tremor frequency and amplitude, as well as by demonstrating entrainability or, in its absence, clear suppressibility during performance of complex tasks in an unaffected limb. Clinical assessments of tremor severity were performed prior to and immediately at the completion of the retrainment session. Longer-term outcome was determined by telephone follow up between 3 and 6 months from completion of retrainment. Baseline entrainability and suppressibility were scored offline by blinded investigators using video from a standardized recording protocol (0–2: 0, none; 1, partial; 2 complete, for each). Tactile stimulation with visual feedback was delivered synchronously by Crescendo at approximately 2/3 of the baseline frequency of the affected limb for approximately 60 minutes, and then at 1/3 of the baseline frequency for another 60 minutes. Patients were instructed to make flexion-extension wrist movements of the most affected hand matching the device stimulation for the duration of the feedback. Intrusion of baseline tremor was discouraged during the performance of the externally paced wrist movements. To that end, training of up to 10 minutes prior to the biofeedback session was conducted to ensure optimal matching of the given rate with minimal intrusion of the baseline tremor. If the tremor was not substantially improved at the end of a single 2-hour retrainment session, the patient participated in a second and, if necessary, a third consecutive-day session. All patients were recruited from the University of Cincinnati Movement Disorders Center. The institutional review board approved the study and patients provided informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographics, baseline tremor scores, and outcome in patients studied

| Tremor scores | Baseline S & E | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Age | Gender | Duration (years) |

Training (days / hours) |

Before | After | S | E | Outcome |

| 1 | 55 | F | 8 | 2 / 4 | 42 | 19 | 1 | 1 | Relapsed after 2 weeks |

| 2 | 66 | F | 10 | 3 / 6 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Relapsed after 6 months |

| 3 | 61 | F | 4 | 2 / 4 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | Relapsed after 3 months |

| 4 | 36 | M | 2 | 2 / 4 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Remained tremor-free at 5 months |

| 5 | 36 | F | 5 | 1 / 2 | 36 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Relapses only with stress at 3 months |

| 6 | 75 | M | 3.5 | 2 / 4 | 45 | 2 | 2 | 1 | Relapsed after 4 months |

| 7 | 57 | F | 5 | 1 / 2 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 0 | Remained improved after 4 months |

| 8 | 41 | M | 3 | 1 / 2 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Remained tremor-free after 4 months |

| 9 | 64 | M | 1.5 | 2 / 4 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 2 | Remained tremor-free after 4 months |

| 10 | 45 | M | 0.8 | 1 / 2 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Remained improved after 6 months |

S = Suppressibility; E = Entrainability

No additional therapies recommended or received during the follow up period for any of the subjects.

2.3. Data Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the combined severity, duration factor, and incapacitation scores of the Tremor subscale of the Rating Scale for Psychogenic Movement Disorders (0–12 per each limb and head [maximum for all five regions: 60]) [2]. A paired t test was used to compare the scores before and after retrainment.

3. Results

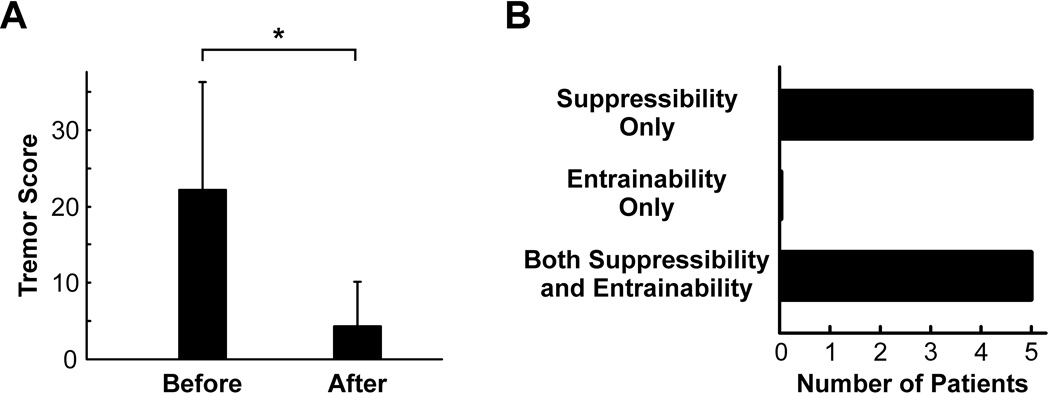

At baseline, suppressibility was more common than entrainability in this cohort (1.5±0.5 vs. 0.6±0.66, p = 0.009), but both were present in half the cohort (Video 1). Entrainment was unfeasible in 5 subjects due to complete suppressibility. Nevertheless, tremor improved across subjects with predominant suppressibility (in whom entrainability was precluded) as well as in those whose tremor was both entrainable and suppressible (tremor score changed from 22.2 ± 13.4 to 4.3 ± 5.5; p = 0.0019) (Table 1) (Figure 1) (Video 2). Three subjects achieved tremor freedom, two of whom had complete suppressibility on examination at baseline (i.e., were non entrainable) (Video 3). Two of these subjects, however, had partial or complete entrainment in another limb or the head.

Figure 1.

A. Tremor scores before and after retrainment. B. Suppressibility and entrainability scores.

A two-hour retrainment session was sufficient for four subjects whereas two consecutive two-hour sessions were needed for five subjects. Only one subject (10 years disease duration) required a third day of retrainment to substantially improved (Video 2). The benefits were maintained for at least 1 week and for up to 6 months, at last follow up. By six months, four patients had experienced relapse whereas six remained markedly improved, including one free of tremor.

4. Discussion

Tremor retrainment appears to be an effective treatment strategy for PsyT patients. Currently used exclusively to establish the diagnosis, entrainment or suppressibility, may be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

As recently proposed, sharing diagnostic signs such as entrainment with patients during the debriefing process serves to illustrate how the diagnosis is made and may be a powerful way of persuading them about the nature of their illness and the futility of proceeding with extensive neurological investigations [3]. Although explaining the diagnosis of a psychogenic movement disorder (or, as we prefer, a “functional movement disorder” [4]) to a patient can be a difficult task, such ability may be assisted by the affirmation of a feature that carries with it both diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Therefore, discussing the presence of entrainment/suppressibility (and its potential as a therapeutic tool) would be expected to facilitate acceptance of the diagnosis, arguably the most important factor in determining good outcome [5].

The retrainment intervention examined here adds further strength to the role of rehabilitation protocols for psychogenic/functional movement disorders. A recent experience was reported for an outpatient, one-week intensive rehabilitation protocol based on “motor reprogramming” applied to patients with functional gait disorder [6]. It is possible, however, that physical therapy- and biofeedback-based treatment protocols may only be associated with sustained long-term benefits when paired with cognitive behavioral therapy [7]. The growing evidence supporting the use of this treatment modality in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures [8, 9] is expected to be translatable to patients with psychogenic/functional movement disorders [10].

A number of limitations of our pilot study must be highlighted. By design, a study examining the concept of retraining needed to be open-label and could not be controlled (e.g., by a “noisy” external pacing that would not necessarily accomplish a rate replacement). The clinician had to encourage patients to accept a tremor rate different than their own, with the explicit goal of “hijacking” their psychogenic tremor and ultimately eliminating the oscillatory behavior. This type of intervention may not have succeeded if patients would not have understood and embraced the principles behind adopting an artificial frequency in order to eliminate their native one. The protocol required a style of coaching by the clinician that is not suitable for application in double-blind placebo controlled conditions (as demonstrated in Video 2). As a result, recruitment for this study was likely biased toward highly motivated patients, ready to embrace their PsyT diagnosis and actively participate in their therapy. Thus, a retrainment strategy may be less applicable to those with severe disability or certain psychopathological profiles, such as somatization disorder. One caveat worth mentioning is that, despite benefits attained, this technique is theoretically capable of producing a different tremor in the affected hand or, perhaps, a new tremor in the previously unaffected one. Finally, the exploratory nature of this study in a selected group of motivated PsyT patients restricts the generalizability of our results, demanding independent confirmation on a wider spectrum of severity and underlying psychopathological backgrounds.

In conclusion, tremor retrainment may be an effective short-term treatment strategy easily deployable at the bedside for patients with psychogenic tremor. Although blinded evaluations may not be feasible for a technique that depends on patient suggestibility and motivation, future studies will be needed to determine the long-term benefits, the effects of “booster” sessions, and the potential synergy of combining retrainment with cognitive behavioral or specialized physical therapy. Neurologists are well positioned to not only deliver the diagnosis but also lead and foster an active role in the care of patients with functional movement disorders.

Supplementary Material

A. Crescendo system (Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, Cleveland, Ohio). B. Prototype software created in LabVIEW to measure tremor, control stimulation cues, provide tremor frequency feedback, and store data.

A participating subject is shown with the study setup, with an electrogoniometer and a channel of stimulation placed on the wrist extensor muscles, looking at the LabVIEW interface which displayed real-time feedback to ensure accuracy of retrainment.

41-year-old man with a 3-year history of psychogenic tremor. The evaluation demonstrates a postural tremor with variability of amplitude and frequency, exhibiting both suppressibility as well as entrainability to slower examiner-provided tapping rates.

55-year-old woman with an 8-year history of chronic bilateral hand and intermittent head tremor, during the first and second retrainment sessions. Visual feedback is provided to ensure adoption of new rate, with initial tactile-only initial stimulation, followed in short sequence by the addition of auditory cueing. Marked improvement is shown at the exit assessment. Note coaching style to encourage patients to accept a tremor rate different than their own.

64-year-old man with 1.5-year history of psychogenic tremor involving the right hand. Notice complete suppressibility of the right-hand tremor, with shifting of the tremor activity to the head. A single retrainment session sufficed for sustained tremor remission (up to 6 months at last follow up).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by a Gardner Family Center Research Grant.

Dr. Espay is supported by the K23 career development award (NIH, 1K23MH092735); has received grant support from CleveMed/Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, and Michael J Fox Foundation; personal compensation as a consultant/scientific advisory board member for Solvay (now Abbvie), Chelsea Therapeutics, TEVA, Impax, Merz, Solstice Neurosciences, Eli Lilly, and USWorldMeds; royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins and Cambridge; and honoraria from Novartis, UCB, TEVA, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Movement Disorders Society.

Dr. Edwards receives royalties from publication of Oxford Specialist Handbook Of Parkinson’s Disease and Other Movement Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2008) and receives research support from a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) grant where he is the PI. He has received honoraria for speaking for UCB.

Dr. Heldman has received compensation from Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies for employment.

Dr. Lang has served on scientific advisory boards for Abbott, Allon Therapeutics, Inc., Biovail Corporation, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Inc., Ceregene, Eisai Inc., Medtronic, Inc. Lundbeck Inc., NeuroMolecular Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Merck Serono, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., TaroPharma, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; has received speaker honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline and UCB; receives/has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, the Michael J Fox Foundation, the National Parkinson Foundation, and the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre; and has served as an expert witness in cases related to the welding industry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors’ roles: AE, ME, and AL conception, design, drafting, editing and revising. AE authored the manuscript. AE, HG-U, CP, NP, and JM undertook clinical assessments on the patients and collected the data. DH adapted the system for retrainment for this study. ME and AL critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: DH is Biomedical Research Manager at Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, the manufacturer of the Crescendo system which was adapted to fit the objectives of this study. However, he did not directly participate in recruitment or analysis of data. AE has received research support from Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies for studies other than the one covered in this article. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest related to the research covered in this article

Full financial disclosures for the previous 12 months:

Dr. Oggioni has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Phielipp has nothing to disclose.

Mr. Cox has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Gonzalez-Usigli has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Pecina has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Mishra has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kim YJ, Pakiam AS, Lang AE. Historical and clinical features of psychogenic tremor: a review of 70 cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26:190–195. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinson VK, Cubo E, Comella CL, Goetz CG, Leurgans S. Rating scale for psychogenic movement disorders: scale development and clinimetric testing. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1592–1597. doi: 10.1002/mds.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone J, Edwards M. Trick or treat? Showing patients with functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms their physical signs. Neurology. 2012;79:282–284. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fdf63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards MJ, Stone J, Lang AE. From psychogenic movement disorder to functional movement disorder: it's time to change the name. Mov Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mds.25562. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espay AJ, Goldenhar LM, Voon V, Schrag A, Burton N, Lang AE. Opinions and clinical practices related to diagnosing and managing patients with psychogenic movement disorders: An international survey of movement disorder society members. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1366–1374. doi: 10.1002/mds.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czarnecki K, Thompson JM, Seime R, Geda YE, Duffy JR, Ahlskog JE. Functional movement disorders: successful treatment with a physical therapy rehabilitation protocol. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, Stone J, Cavanagh J, Murray G, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77:564–572. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228c0c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaFrance WC, Jr, Miller IW, Ryan CE, Blum AS, Solomon DA, Kelley JE, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaFrance WC, Jr, Reuber M, Goldstein LH. Management of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 1):53–67. doi: 10.1111/epi.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaFrance WC, Jr, Friedman JH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychogenic movement disorder. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1856–1857. doi: 10.1002/mds.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Crescendo system (Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, Cleveland, Ohio). B. Prototype software created in LabVIEW to measure tremor, control stimulation cues, provide tremor frequency feedback, and store data.

A participating subject is shown with the study setup, with an electrogoniometer and a channel of stimulation placed on the wrist extensor muscles, looking at the LabVIEW interface which displayed real-time feedback to ensure accuracy of retrainment.

41-year-old man with a 3-year history of psychogenic tremor. The evaluation demonstrates a postural tremor with variability of amplitude and frequency, exhibiting both suppressibility as well as entrainability to slower examiner-provided tapping rates.

55-year-old woman with an 8-year history of chronic bilateral hand and intermittent head tremor, during the first and second retrainment sessions. Visual feedback is provided to ensure adoption of new rate, with initial tactile-only initial stimulation, followed in short sequence by the addition of auditory cueing. Marked improvement is shown at the exit assessment. Note coaching style to encourage patients to accept a tremor rate different than their own.

64-year-old man with 1.5-year history of psychogenic tremor involving the right hand. Notice complete suppressibility of the right-hand tremor, with shifting of the tremor activity to the head. A single retrainment session sufficed for sustained tremor remission (up to 6 months at last follow up).