Abstract

The classical neurovascular unit (NVU), composed primarily of endothelium, astrocytes and neurons, could be expanded to include smooth muscle and perivascular nerves present in both the up and down stream feeding blood vessels (arteries and veins). The extended NVU, which can be defined as the vascular neural network (VNN), may represent a new physiological unit to consider for therapeutic development in stroke, traumatic brain injury, and other brain disorders [1]. This review is focused on traumatic brain injury and resultant post-traumatic changes in cerebral blood-flow, smooth muscle cells, matrix, BBB structures and function and the association of these changes with cognitive outcomes as described in clinical and experimental reports. We suggest that studies characterizing TBI outcomes should increase their focus on changes to the VNN as this may yield meaningful therapeutic targets to resolve post-traumatic dysfunction.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, juvenile traumatic injury, blood-brain barrier, neurovascular unit, cerebral blood flow, smooth muscle cells, matrix

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) from clinic to pre-clinical rodent models

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a significant public health issue with 53,000 deaths each year in the U.S. [2]. Overall, improvement of personal protection in motor vehicle accidents was associated with a decrease of the TBI-related deaths between 1980 and 2007 [3, 2]. Gender and age also impact TBI death rates, with 3 times more deaths in males versus females and juvenile and elderly populations compared to adult [3, 2]. Clinically, TBI is divided into severe, moderate and mild categories. Mild TBI is defined by a loss of consciousness of short duration, and the absence of skull fracture and modification in classical neuroimaging, CT-scan and diffusion MRI. In addition to the mortality rate associated with TBI, it is also important to consider the resultant long-term cognitive morbidity and its major impact on everyday life in those patients that survive. Moreover, the number of the patients suffering from mild-TBI is very likely underestimated because most of the time these patients are seen in the outpatient setting rather than the emergency department, and are then not included in TBI patient statistics [3]. Unfortunately, most mild TBI patients also suffer with long-term disabilities similarly to those with more severe TBI [4]. Clinical observations of these long-term changes strongly suggest that TBI is not only an acute event but is also a complex brain disease, sharing features of other brain pathophysiologies such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5–7]. In fact, while gross motor skills generally improve with time, cognitive deficits may linger and further deteriorate. For example, three months after mild TBI, 17% of children show cognitive and neurobehavioral problems [8, 9] and 30% of adults perform poorly on memory tasks and report ongoing memory and concentration difficulties in daily activities [10] with many neurobehavioral problems persisting for 6–12 months [11]. Interestingly, the profile of mild TBI in children, aged 8–17 years at injury, includes problems with memory, psychomotor skills, speed, and language throughout a 12 month follow-up period [12]. Clinical studies have also shown that early-life TBI can be a major cause of death and disability [13, 14] and lasting cognitive problems can increase mortality risk into the second and third decades if injury occurred any time prior to age 40 [15–17]. Repeated TBI is now established as a risk factor for dementia with multiple underlying neurodegenerative processes and changes in cerebral blood flow, as is common for sports-related activities like football and boxing [18, 6, 19–22]. However, long-term consequences of a single TBI are less known and they depend on the intensity, the location, the age and other factors. Clinical observations suggest that diminished cognitive reserve from a single TBI may lead to premature aging and neurodegeneration [23–25] which may be related to widespread volume loss in frontal and temporal areas seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) one year later [26].

Clearly, survivors of TBI endure lifelong consequences and they warrant close attention from the medical and scientific community. To better understand the underlying mechanisms of TBI, it is important to consider that the brain is not only composed of neurons but a very complex network of neurons, glial cells (e.g. astrocytes), and cerebral blood vessels (endothelium, smooth muscle layer and perivascular matrix) as part of a physiological entity. In fact, cerebrovascular dysfunction is clinically observed with a decrease in cerebral blood flow, glucose consumption and oxygen extraction [27]. These changes in metabolism are related to both mitochondrial dysfunction and changes in vascular properties [27]. However, the complex array of long-term physical and behavioral effects and their underlying mechanisms after TBI are poorly understood. This review describes the sometimes-dramatic changes that can occur in the cerebrovascular compartment after TBI, changes that may also be linked to neurodegenerative disease and AD.

Definition of Vascular Neuronal Network: from capillary to large cerebral blood vessels

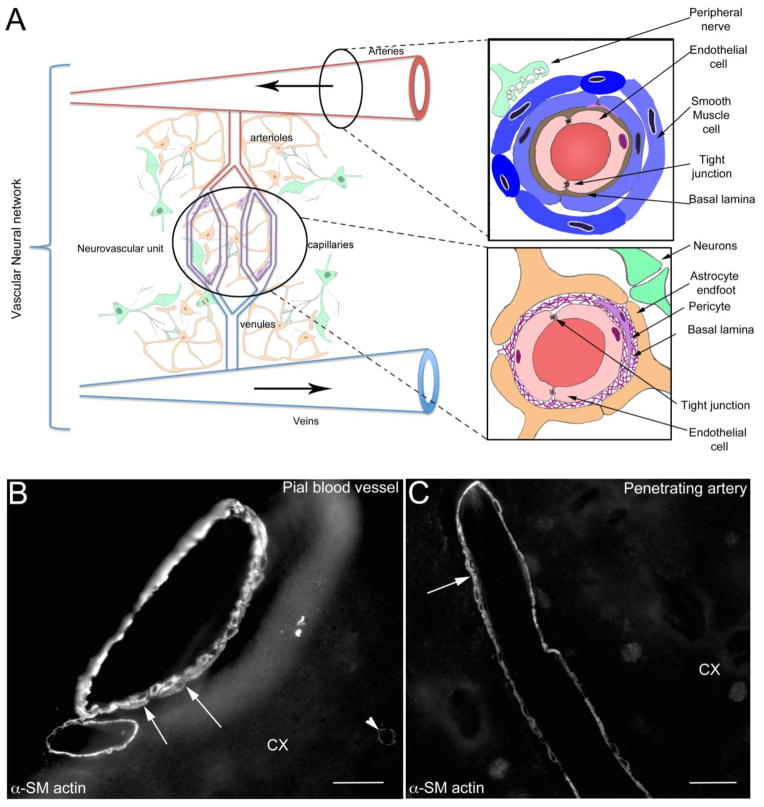

The neurovascular unit (NVU) was originally defined as a physiological unit composed of the vascular bed, astrocytes and neurons [28]. Over time, this definition changed to a physiological unit formed by endothelium, astrocytes and neurons, leaving out certain components of the vascular bed such as smooth muscle. However, neither definition includes the entire vascular tree. Recently, Zhang et al proposed to revise the physiological unit by including both the downstream venous vasculature and upstream arteries [1] (Figure 1). This expanded NVU includes smooth muscle and perivascular nerves [1] and was named the vascular neural network (VNN) [1]. The VNN has been proposed as a new physiological unit to consider in stroke disorders [1]. As we will illustrate in the following sections, TBI also causes several modifications to the VNN. As proposed in Zhang et al. 2012 [1], the consequences of changes in vascular smooth muscle, arterial endothelium and perivascular nerve fibers are understudied in the vascular injury following TBI. Here we propose that long-term phenotypic transformation in the VNN could be in part responsible for the cognitive dysfunction after TBI. We will first review the cerebral vasculature system, which presents with regional differences and specializations.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic drawing of the vascular neural network (VNN, adapted from Zhang et al. [1]). The VNN includes the neurovascular unit (NVU), which is composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, basal lamina, astrocyte and neurons. The VNN also includes the cells that form and innervate larger blood vessels including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and peripheral nerves. By definition, the feeding blood vessels running in the subarachnoid space are part of the VNN. This new physiological unit includes all the cells contributing to the maintenance of cerebral blood perfusion.

B) Alpha Smooth muscle actin (α-SM actin) staining of pial blood vessels on the surface of the cortex (CX). A multilayer of SM cells is present (arrows) in the media of the pial blood vessel. Each of the individual SM cells may potentially have different functions, contractile and/or secretive. Staining of the contractile protein α-SM actin (arrowhead), present in pericytes, outlines some capillaries.

C) α-SM actin staining in cortical penetrating blood vessel (CX) is outlining one or two layers of of smooth muscle cells (arrows) in the vascular wall of penetrating artery. In contrast with the vessels in the periphery and large cerebral feeding arteries, little is known about the effects of brain injury on phenotypic changes of the smooth muscle cells in the pial and penetrating blood vessels.

Bar B, C = 40 μm

1) General anatomy of the cerebral vasculature

The brain vascular system is divided in two categories of blood vessels: extraparenchymal and intraparenchymal cerebral blood vessels. Extraparenchymal vessels include the main feeding arteries (i.e. basilar, middle cerebral arteries), pial blood vessels and penetrating blood vessels. The penetrating arteries enter the brain parenchyma within the Virchow Robin space, which is filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [29]. Extraparenchymal artery tone, including penetrating arteries, is under the influence of perivascular nerves, which run along the smooth muscle layer [29]. Intraparenchymal blood vessels start where the Virchow Robin space disappears. Intraparenchymal arteriole tone is under the control of astrocytes and some specific neurons [30, 29]. It is interesting to note that perivascular nerves also have trophic roles in the smooth muscle layer [29]. The proximity of the astrocyte layer to the penetrating blood vessels and microcirculation raises the question of the influence of this layer on the physiological properties of the brain vasculature. All cerebral blood vessels are unique by the presence of a barrier blood and brain compartment located in the endothelium.

2) Endothelium and blood-brain barrier

One of the common features in the cerebral vasculature system is the presence of a blood-brain barrier (BBB) at the level of the endothelial cells independent of the size of the blood vessels (extra and intraparenchymal blood vessels). At the level of endothelial cells, the BBB is subdivided into three main features [31]: The “physical barrier” of the BBB is formed by junctional complexes between endothelial cells of cerebral blood vessels that prevent paracellular diffusion, forcing most substances across the endothelial barrier in order to enter or exit the brain. The junctional complexes between endothelial cells are of two types: adherens junctions (i.e. platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule and vascular endothelial-cadherin) and tight junctions (composed of claudins, occludins, and zona occludens (ZO) proteins including ZO1, ZO2, ZO3). The “transport barrier” of the BBB is composed of specific transport proteins located on the luminal and abluminal membranes of endothelial cells that allow for the control of nutrients, ions and toxins to cross the endothelial layer between the blood-stream and brain [31, 32]. There are several transporters that are critical for the delivery of nutrients across the BBB such as glucose transporter 1 (GLUT 1), monocaroxylate transporter 1 and 2 (MCT1, MCT2), and L-system neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT 1). ATP binding protein (ABC) family transports a wide range of lipid-soluble compounds out of the brain endothelium with consumption of ATP. In the BBB, examples of ABC transporters for efflux transport are P-glycoprotein (P-gp), multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) [32]. These efflux transporters are proposed as “gatekeepers” of the brain, keeping tight control over substances allowed to enter the CNS through the endothelial cell barrier. In addition to these transporters, trancytosis is a mechanism observed in brain endothelial cells to facilitate the passage of large proteins and peptides across the BBB. This mechanism is either receptor mediated (receptor mediated transcytosis), or occurs via adsorption (adsorptive-mediated transcytosis). Examples of substances that cross the BBB by these mechanisms include insulin for the former and albumin for the latter. The “metabolic barrier” of the BBB is a combination of intracellular and extracellular enzymes such as P450 and monoamine oxidase. The enzymes inactivate molecules capable of penetrating cerebral endothelial cells. The BBB is a dynamic structure which evolves throughout an individual’s life. Proteins involved in tight junction formation are observed at 14 weeks in human fetal brain capillaries, thus limiting the movement of macromolecules during early brain development [32]. Then, the BBB continues to mature after birth. For example, P-gp expression increases in luminal endothelial cell membranes from postnatal day (P)7 and reaches a plateau by P28 in rat brain [32]. With aging and neurodegenerative disease, multiple structural changes occur including decreased P-gp and low-density lipoprotein-related protein 1 (LRP1) [33, 34]. Despite the presence of the BBB in all cerebral blood vessels, there are variations in the expression of the proteins in the endothelial cells. While phenotypic endothelial heterogeneity is known in peripheral organs, it has been under-explored in the brain. Few studies have evaluated the rate of transcytosis or the organization of junctional complexes, and the expression of some enzymes such as Na+/K+ ATPase differ among arterioles, capillaries, and venules [35]. On a similar note, it has been reported that some transporters, such as P-gp, are also differentially expressed in large vessels as compared with capillaries [36–39]. In fact, P-gp expression gradually increases in rat brain vasculature from a low level in the largest arterioles (20 to 50 μm) to a high level in capillary beds and venules [39]. In addition to variation along the vasculature, there are regional differences in the level of transporters in capillary beds that could depend on brain synaptic activity. For example, a low level of GLUT1 is observed in the paraventricular and supraoptic hypothalamic nuclei compared to cortex positively correlating with energy demand [40]. After brain injuries, it is likely that the endothelium will react differently along the vascular tree (artery, capillary and vein) as well as between brain regions depending on the phenotype of the initial injury.

3) Cerebrovascular matrix

Another component of the VNN is the cerebrovascular matrix. It is chiefly composed of collagen IV, laminin, entactin/nidogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, and the heparan sulfate proteoglycans perlecan and agrin. These substances help regulate homo- and heterotypic cell signaling via interactions with cell receptors such as integrins [41, 42]. During development, the matrix, which accounts for 40% of developing brain volume [43], organizes the extracellular space for optimal cellular functions including cellular migration, morphogenesis, and in neurons, synapse formation, synaptic stability, and proper cell signaling [44]. Early during brain development, fibronectin is very prominent and supports new blood vessel formation (angiogenesis), but then is less widely expressed in favor of laminin in the adult brain [45]. At the level of capillaries and postcapillary venules, the matrix layers into two distinct cell associated basement membranes (BM), a parenchymal glial limitans formed by astrocytes, composed mostly of laminin 1 and 2, and a vascular wall endothelial BM [46]. The glial limitans normally ‘limits’ leukocyte infiltration into the parenchyma of the brain and collectively these two membranes support barrier function.

Matrix remodeling can occur via a number of proteases including the zinc- and calcium-dependent matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). MMPs are produced and secreted in zymogen form (ProMMPs) and must then be activated by other MMPs (typically by MMP-2 or MMP-3). Likewise, their activity is also regulated by tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs). Some MMP’s, such as MMP-2, are constitutively expressed, thereby providing ‘on the fly’ remodeling, while others are activated after injury as part of the neuroinflammatory response, including MMP-3 and MMP-9. In addition to processing the matrix, MMPs appear to have other important roles in activating cells. For example, stressed and dying neurons release MMP-3, which in turn leads to microglial activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [47]. Furthermore, different cell types produce different MMPs. Astrocytes produce MMP-9 and MMP-2, the latter at their endfeet, while endothelial cells produce MMP-9, pericytes produce MMP-3 and 9, smooth muscle cells produce MMP-1 and microglia also produce MMP-1 as well as MMP-7 and MMP-9. After brain injury, infiltrating leukocytes are a major source of MMPs.

4) Smooth muscle in brain vessels

The cerebral blood vessels (extra and intraparenchymal types) contain a smooth muscle layer in their vascular wall (Figure 1). The cortical arterioles (ranging from 10 to 20 μm) contain one to three layers of smooth muscle cells (SMC) (Figure 1) [48] and can be stained and visualized with alpha smooth actin (Figure 1) [49]. Vascular SMC are already specialized during development contributing to vascular tone and regulation of blood vessel diameter, blood pressure, and blood flow distribution [50]. Additionally, SMCs and SMC-like pericytes are essential for appropriate vascular maturation and formation of functioning vascular networks during embryogenesis [51]. During vascular development, SMCs and pericytes also contribute to secretion of extracellular matrix molecules like collagen, important in the mechanical properties of mature blood vessels [52, 53]. Once SMCs are differentiated in adult blood vessels, those cells proliferate at an extremely low rate, show low synthetic activity, and express a repertoire of contractile proteins, ion channels, and signaling molecules required for the cell’s contractile function [54, Somlyo, 2003 #2813]. In addition to the alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMa), the contractile functions of SMCs are associated with smooth muscle-myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC), smoothelin-A/B, and SM-calponin [55]. Contractile SMCs are elongated, spindle shaped cells, and form a contractile apparatus with filaments composed of the proteins described previously [55]. In the adult vasculature, a small number of synthetic SMCs are present which are less elongated and have a cobblestone morphology [55]. Synthetic SMCs contain a high number of organelles involved in protein synthesis, and exhibit higher growth rates and higher migratory activity than contractile SMCs. Smemb/non-muscle MHC isoform-B and cellular retinol binding protein (CRBP)-1 are good markers for synthetic SMC. They are upregulated when MHC is decreased in the proliferating SMCs [55]. Both subtypes co-exist in the vascular wall, but the ratio of synthetic and contractile SMCs changes as a function of differences in the vascular environment depending of the physiological situations. In fact, SMCs within adults preserve high plasticity and can undergo changes in phenotype and vascular remodeling in response to vascular injury or disease [54]. This process is highly studied in the periphery and is starting to gain attention in brain injuries and diseases [56, 1]. However, little is known about the large feeding cerebral arteries, but to best of our knowledge there is no such study showing phenotypic changes in the smooth muscle layer of the pial and penetrating blood vessels after traumatic brain injury. The possible changes, and the potential consequences of these changes on long-term blood-brain perfusion will be discussed next.

Early changes in VNN after TBI

TBI is characterized by a primary injury resulting from a direct or indirect biomechanical force on the brain, which is associated with a complex cascade of secondary events. The secondary injuries include various changes in cerebral blood-flow (CBF), hypo-metabolism, increased intracranial pressure, edema formation and inflammation [57–60]. Similar vascular changes were observed in mild repetitive TBI [19]. These secondary cerebrovascular injuries in TBI, as we will next discuss in greater detail, share some molecular mechanisms with stroke.

1) Acute changes in the CBF after TBI

The cerebral vasculature is in the first lines affected after TBI, with significant changes in CBF; either decreased or increased ischemic or oligemic levels depending on injury severity, and on the time and anatomical location of the CBF measurement [61, 19]. Clinical and experimental data indicate that the most profound reductions in CBF are found in and around contusion injuries. On the other hand, diffuse injuries result in very low reductions or even increases in blood flow, at least at initial time points following TBI [62–66, 60]. TBI induces vasospasm in the large feeding blood vessels between 3 to 7 days post-injury in patients who have suffered blast traumatic brain injury (bTBI) such as military personnel wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq [67]. Cerebral vasospasm is characterized by chronic vascular hypercontraction of large pial blood vessels, which is followed by cell proliferation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and arterial occlusion [67]. Moreover, impairment in cerebral autoregulation properties in adults [68] and in the pediatric population [69–71] with young age is a significant predictor of CBF dysfunction [72]. In the pediatric population, this impaired cerebral autoregulation is further associated with overall poor outcome [73, 74, 69], which is confirmed by studies in juvenile animal models such as fluid percussion injury (FPI) in piglets [75].

In a cortical contusion model, decreased CBF was characterized by a lack of perfusion in the core within minutes of injury [64, 60] indicating that high reduction in CBF close to the impact site often reaches an ischemic threshold. Alternatively, other models showed a widespread reduction in CBF involving the entire brain, without reaching ischemic values in most cases, and with recovery over time [64]. Alterations in CBF may contribute to and be exacerbated by secondary injury, as decreased blood supply is associated with reduced energy metabolism in the brain tissue of several TBI models [76–78]. During the first week after TBI, glucose metabolism is likewise impaired in adults and juveniles both in the clinic and laboratory models. For example, poor neurological outcome was associated with increased lactate, measured by proton spectroscopy, in infants and children 6 and 9 days after closed head injury [76, 79]. In juvenile rats, a time course of brain metabolites also revealed global increases in lactate (in both ipsi and contralateral hemispheres to the injury) at 4h until 24h after TBI [78]. Increased lactate likely results from increased glycolysis, a consequence of the decreased CBF described above. Altogether, these data show that TBI-induced changes in VNN properties can lead to widespread functional damage with visible consequences on tissue integrity.

2) Vascular modifications: SMC first in line

Some of the cellular and molecular changes within the VNN for TBI-related changes to CBF and dysfunctional autoregulation are reviewed in this section. Some of the possibilities are alterations in endothelin-1, decreased nitric oxide (NO) levels, cyclic guanosine monophosphate and cyclic adenosine monophosphate as well as changes in K+ channel activation. Modifications in the level of expression of these molecules can affect cerebrovascular tone and therefore the cerebral autoregulatory capacity [75, 80].

As indicated before, NO signaling has been shown to be involved in the regulation of cerebrovascular tone [29]. Although NO changes in TBI have been studied for several years, its role is still controversial. In fact, the activity of endothelial NOS (eNOS) exhibits a bi-modal change after TBI with an initial brief increase for a few minutes followed by a decrease to ~50% of baseline levels for 7 days before normalizing [81, 82]. These decreases of constitutive NOS activity may contribute to altered CBF and cerebral autoregulation, in combination with some changes in properties of the VNN such as changes in the contractility of the SMCs. Administration of an NO donor like sodium nitroprusside (SNP) prevents the reduction of CBF, but does not reverse autoregulatory impairment after FPI in the juvenile piglet model [83]. The complexity of the role of NO in TBI pathophysiology is illustrated in the variety of the observed changes, with some researchers observing decreased eNOS activity [81, 82], while other groups observing an increase in eNOS and iNOS expression at two and three days post-injury in a rodent TBI model [84]. This increase of the eNOS and iNOS was related to peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative damage post-TBI [84]. The presence of eNOS post-TBI was related to the preservation of the CBF in the rodent model of TBI using the eNOS−/− knockout mice [85]. As mentioned previously, inducible NOS (iNOS) expression and activity increases in neurons, macrophages, neutrophils, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, reaching peak levels between 4h and 48h after injury [82, 86–88]. Unfortunately, up-regulation of iNOS results in a harmful increase of tissue NO [82], well known to contribute to neuroinflammation, apoptosis, excitotoxicity, energy depletion, and uncoupling of NOS with subsequent production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [89–91]. It is likely that this increase in NO is also very harmful to the SMC, endothelial cells and matrix. In fact, some recent work using Caveolin-1−/− knockout mice in stroke models showed the involvement of the formation of the NO from eNOS is responsible for increased MMP involved in degradation of the matrix and disruption of the BBB [92]. In addition to NO signaling, endothelin-1 is also involved and contributes to changes in the pericyte-SMC, with a decrease in αSMA during the first hours after TBI [93]. Similar observations have been made in in vitro models of SMC exposed to blast injury showing a smoothelin mRNA decrease and absence of SM-MHC in relation to vascular dysfunction after blast-TBI [67]. Additional molecular changes have been observed in other proteins such as calponin (Cp) in rodent-TBI models [94]. Cp expression in the SMC is significantly increased during the first 48h in association with the enhanced vasoreactivity. This modification is under the control of the endothelin pathway [94]. Inhibition of Cp phosphorylation mitigates changes in vasoreactivity post-TBI and is associated with improved CBF [94]. Other mechanisms associated with the immediate decrease in peri-contusional blood flow post-TBI have been proposed. Decreased CBF is not caused by arteriolar vasoconstriction, but rather by injury-induced formation of microthrombi in 33% of arterioles and by rolling leukocytes and platelet activation in 70% of venules [95].

As mentioned earlier, cerebral vasospasm is possibly associated with extracellular blood with effects on perivascular nerve fibers or extracellular matrix remodeling during the first week post-TBI, which contributes to dysfunctional brain perfusion.

3) Changes in perivascular nerve fibers following TBI

In feeding arteries, cerebrovascular dysfunction could also be associated with changes in the autonomic system. As discussed above, the perivascular nerve plexus is part of the neurogenic regulation of the vascular tone of the pial and large feeding arteries. Several studies have shown that the cerebrovascular response to several vasoactive substances is impaired after TBI [96, 19, 97]. In addition to the changes observed in SMC properties, the perivascular nerve bundle also shows significant changes during the first week after TBI in various vascular beds including the internal carotid, vertebral arteries, basilar artery and middle cerebral artery [98]. The authors describe a decrease in the number of perivascular plexus nerve fibers peaking at 24h after injury, with some vascular beds experiencing a decrease in perivascular plexus nerve fibers up to 7 days post-injury [98]. This modification of the perivascular nerve bundle could be attributed to the presence of subarachnoid blood [99]. In fact, the direct contact of blood is known to cause the disappearance of nerve fiber labeling usually around 3 days after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) onset [99]. It is associated with a decrease in the concentration of vasoactive substances like acetylcholine and VIP but also peptides like substance P and CGRP. The direct consequence is absence of neurogenic control of vascular tone. Ueda and collaborators [98] showed some sort of recovery of the perivascular nerve bundle, but additional studies may be needed to determine whether the fibers ultimately recover all of their functions to insure correct blood perfusion.

4) Changes in the matrix following TBI

After TBI, the extracellular matrix can be impacted by the upregulation of several MMPs. After experimental contusion to the adult mouse brain, MMP-9 rapidly increases (3 hours after injury), peaks after 24 hours, and remains elevated for at least 1 week [100]. MMP-2 is also acutely elevated in rodent TBI [101]. In turn, MMP-3 activity is increased more chronically after TBI in rats and may play a role in synapse restoration [101]. In the immature P7 rat brain after TBI, MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels are elevated at the site of injury [102]. In human TBI, relatively less is known about MMP expression. A very recent prospective study of 8 severe TBI human patients using cerebral microdialysis and CSF analysis demonstrated significant increases in several MMPs [103]. In particular, MMP-8 and MMP-9 increased very rapidly after severe TBI but then declined by 48 hours, only to be followed by spikes in MMP-2 and MMP-3, followed by a gradual increase in MMP-7. Similar elevations in MMPs have also been seen in patient serum after TBI, and may therefore ultimately serve as a biomarker for TBI onset and severity [104].

5) Early dysfunction in the endothelial cells

TBI’s effect on the endothelium and its barrier differs depending on the injury model, age at injury, and severity of impact. As described previously, the effects of TBI on barrier properties have mostly been studied during early time points after injury. These BBB changes can range from complete rupture and leakage to simply an altered biochemical and/or functional profile. Thus, although the BBB is often referred to as “open” or “closed”, these terms may have a misleading connotation, as all brain barriers are dynamic structures made up of and regulated by various proteins.

Experimental models report disruption of the tight junctions. Interestingly, in some models, the tight junction disruption is not observed by electron microscopy during the first hours after TBI [48]. Most of the time the “opening” of the BBB is visualized with stains like Evans blue or anti-IgG staining. It is thought that TBI induction of BBB “opening” occurs within the first day after injury and contributes to vasogenic edema formation [105]. In a controlled cortical impact (CCI) juvenile (P17) TBI model, IgG extravasation levels are high near the injury site and surrounding tissue at 1 and 3 days, and are substantially lower at 7 days [4]. In addition to these measures of “BBB permeability”, some studies report continued alteration in tight junction proteins, such as claudin 5. At multiple time-points post-injury, BBB dynamics often coincide very well with the expression levels of tight junction markers. In the short term after injury, pial and intracerebral vessels have decreased claudin 5, as evidenced at 2 days after cortical cold injury in rats [106]. A CCI study has looked at monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), which are expressed on membranes of endothelial cells, neurons, microglia, and astrocytes [107]. MCTs in brain lysates increased in the first week post-CCI in young adult rats at P35 and P75 [108]. In a comparable study, only young rats had improvements in behavior and preserved cortical tissue after a 1-week post-injury ketogenic diet, which increased MCT levels [109].

In summary, there is a wide range of changes in early time points after TBI in the brain vasculature at the level of the endothelium, matrix and SMC. All these changes strongly suggest that TBI is also a cerebrovascular injury with major dysfunctions in VNN early on after the primary impact. Numerous studies have so far focused on neuronal cell death and long-term recovery after TBI. However, comparatively little is known about the long lasting changes in the brain vasculature and their potential consequences for functional outcome.

VNN dysfunction at long term post-TBI: possible association with cognitive dysfunctions

CBF changes are observed over weeks and months after traumatic brain injuries with impact on glucose and oxygen extraction [110, 98, 111]. Despite the difficulty in directly linking vascular dysfunction to behavioral outcome [110], the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind these changes in TBI are understudied and not well known. We believe additional studies will be needed to have a better view of the link between brain cerebral blood vessels and functional outcomes after TBI. It is also critical to address whether these changes affect behavioral outcome for months and years after the initial impact. BBB dysfunction has been proposed to play a role in AD, Parkinson disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), stroke, epilepsy, tumors, as well as HIV-infection and psychiatric disorders [112, 113]. As we discussed previously, TBI induces vascular dysfunction and possibly chronic vascular disease. In the periphery, SMC phenotypic switching is observed in vascular disease and contributes to its development and/or progression. Unfortunately, comparable research endeavors are scarce in TBI, especially when a single injury occurs.

1) Endothelial changes: clues for long-term phenotypic transformation of VNN

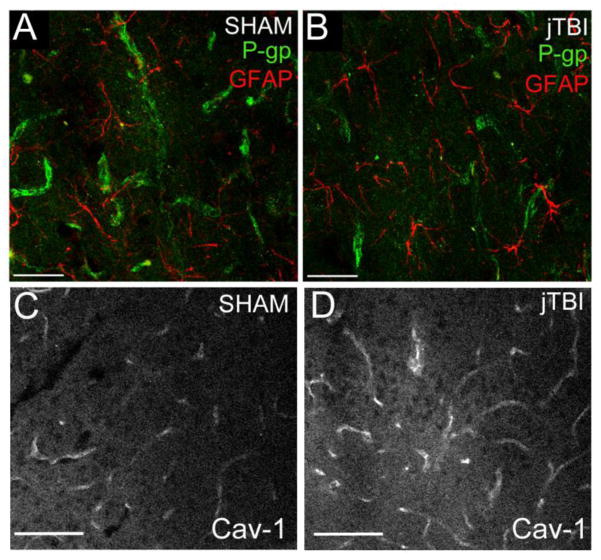

TBI induces altered endothelial cell properties at the structural level early on after injury onset. For a long time, the opening of the BBB was considered a transient event that normalized within one week, as we observed in our rodent TBI model [4]. However, the BBB remains open as late as 30 days after the insult in a stroke model [114], suggesting long lasting changes of the endothelium properties. In a juvenile TBI (jTBI) model, IgG is not detected near the injury site and staining is only observed in the regions without a barrier, such as the median eminence at 2 months post-injury [115]. In addition to these measures of “BBB permeability”, changes in claudin 5 expression are observed several weeks after BBB opening resolved. In fact, claudin 5 is up-regulated up 2 weeks post-injury after sustained epidural compression of rat somatosensory cortex [116]. In a jTBI model, claudin 5 expression in the main penetrating blood vessels is significantly increased at 2 months post-injury, suggesting some compensatory mechanisms and phenotypic transformation of the endothelial cells. In parallel to increased claudin 5, P-gp is significantly down regulated in the endothelium in several cortical regions associated with aberrant protein accumulation (i.e. beta-amyloid (Aβ)) and memory dysfunction [115] (Figure 2). While P-gp is well known as an efficient gatekeeper on the luminal side and is often pharmaceutically by-passed to allow efficient drug delivery, its expression is influenced via several distinct molecular pathways and its putative role in disease and post-trauma is just emerging [115]. P-gp is decreased on endothelial cells in aged human and AD brains as well as in aging rodents [33, 34]. In addition, P-gp knock-out models have increased amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition after injection of Aβ in the brain [117], suggesting P-gp as a key player in the clearance of Aβ and other toxic substances from the brain parenchyma. Furthermore, some studies in the AD field propose that sporadic Aβ accumulation within the brain depends largely on the effectiveness of its clearance through the BBB [118, 119]. Collectively, these observations suggest that BBB integrity represents a complex and dynamic pattern that merits attention at many stages after TBI.

Figure 2.

A, B) P-gp immunostaining (green) is present in endothelial cells, as shown in close proximity to the end-feet of GFAP-positive astrocytes (red) in both (A) sham and (C) juvenile TBI (jTBI). P-gp staining is significantly decreased in jTBI compared to sham animals at 2 months post-injury (kindly provided Pop et al. [115]).

C, D) Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) staining is present in endothelial cells in sham (C) and jTBI (D) rats. Increased Cav-1 staining intensity in the jTBI compared to sham animals at 2 months post-injury reinforces the idea of phenotypic transformation of the endothelial cells at long-term post-TBI.

Bar A, B = 50 μm; C, D= 100 μm

The caveolin protein family takes part in caveolae formation, which is known to function in endocytosis, transcytosis, and exocytosis in endothelial cells [120, 121]. Caveolin-1 (cav-1), one of 3 isoforms, is present in brain endothelial cells [122, 36]. Cav-1 also serves to modulate the activities of a wide variety of signaling molecules, including inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [123–125]. Its expression is increased in the endothelium during the first week after brain cold injury [126, 106]. In support of the phenotypic transformation of the endothelium after jTBI, we observed an increase in cav-1 staining in brain cortical blood vessels at 2 months post-injury (Figure 2). This observation also suggests that cav-1 could play a role in changes of claudin 5 and P-gp expression that occur after TBI. Interestingly, cav-1 was associated with stabilization of claudin 5 within the caveolae [127] and a decrease of P-gp activity [128]. These results support the idea of phenotypic transformation of the endothelial cells up to 2 months after TBI and they possibly contribute to some of the cognitive dysfunction reported in clinical studies. Along the same idea, long-term phenotypic changes in matrix and SMC are very likely happening after TBI.

2) Possible SMC transformation at long term after TBI

Vascular biology in the periphery clearly demonstrates that the high plasticity of the SMC for changing from the contractile to secretive phenotype is a critical process in vascular injury-repair [50]. The changes in SMC phenotypes also depend on the environment and contribute to a multitude of human diseases such as arteriosclerosis [50]. In the carotid artery after hypoxia, SMC differentiate from contractile to secretive phenotype under a VEGF-driven mechanism [56]. The SMC loses its contractile properties via a decrease of the MHC and increase of SMemb/non-muscle MHC [56]. VEGF levels change in TBI [129, 130], but so do other growth factors and cytokines. SMC phenotypic modulation in the periphery is under the control of several molecular pathways that could be present after TBI like PDGF BB, PDGF DD, and IL-1β. All these molecular pathways can induce rapid downregulation of expression of multiple SMC differentiation marker genes, including those encoding SM α-actin, SM MHC, and calponin. A wide range of signaling pathways are involved in the responses to these agents including ERK, p38 MAPKs, and Akt. Moreover, differentiation and proliferation are not mutually exclusive and many factors other than SMC proliferation status influence the SMC differentiation state. Despite the paucity of knowledge of this process in the cerebral blood vessels after TBI, it is highly possible that the early changes in the VNN environment would induce long-term changes in the SMC phenotype, from contractile to secretive. The extra and intraparechymal blood vessels become pathologic with direct consequences on the blood flow, oxygen and glucose extractions. Long-term dysfunction in the vascular tree is possibly involved in the cognitive dysfunction following TBI.

In this section, we reviewed some potential molecular mechanisms that might contribute to the vascular phenotypic changes. There are several open questions. How does inflammation contribute? Is there any change in the peripheral nerve innervation phenotype? How do these changes in VNN affect the behavior outcomes? All these questions require future investigation.

Summary, significance, and unanswered questions

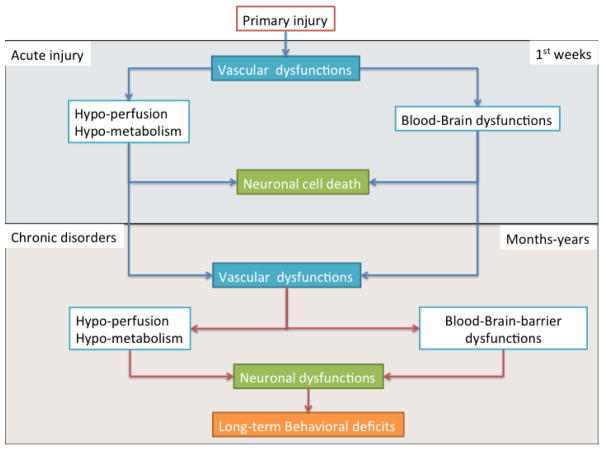

Originally, the VNN was defined as a new physiologic unit for the consideration of stroke drug development. Based on considerable evidence in the literature, we propose that the VNN could also be a physiological unit to consider in the treatment of secondary injuries post-TBI. To date, few experimental TBI studies have focused on the timeline and/or pattern of changes in the VNN in association with behavioral outcomes [115, 4, 110]. We have raised several unanswered questions that we believe need to be addressed in future TBI studies (summarized in table 1). The changes that occur immediately post-injury in the VNN are likely associated with long-term phenotypic transformation with consequences including impairment in blood-brain perfusion (Figure 3). We propose that a possible root cause of observed clinical patterns of long-term behavioral dysfunction from TBI could be abnormal SMCs, Matrix and BBB, where compromised cerebrovascular integrity persists over time and hinders full recovery. Our data and the literature outlined in this review support the idea that TBI may promote VNN dysfunction, which evolves over time. For example, in jTBI, protein trafficking/clearance is affected with the decrease of P-gp, which could potentially contribute to long-term sequelae [115]. Further studies targeting the VNN are needed to address whether these changes in cerebral blood vessels are interconnected with behavioral outcomes, or whether they are parallel events occurring independently of one another in the same trauma-affected brain. On the other hand, treatments that restore VNN may contribute to preserved tissue and neuronal viability, leading to physiological improvement and restored cognitive function.

Table 1. Summary of Unanswered Questions for TBI Research.

Table 1 presents a summary of the unanswered questions raised during the review of the literature.

| Some unanswered questions for TBI research |

|---|

| 1 What are the long-term consequences of a single TBI and how are they impacted by the injury intensity, location, age and other factors? |

| 2 What is the complex array of long-term physical and behavioral effects and their underlying mechanisms after TBI and how are these changes linked to neurodegenerative disease and Alzheimer’s disease? |

| 3 What phenotypic endothelial heterogeneity exists in the normal and pathological brain? |

| 4 What changes occur in the smooth muscle cell layer of large feeding cerebral arteries in pial and penetrating blood vessels after traumatic brain injury? |

| 5 What is the exact role of NO changes in TBI? |

| 6 To what extent do perivascular nerve bundles functionally recover after TBI? Is there any phenotypic change at long-term after the brain injury? |

| 7 How is MMP expression and activity affected in human TBI? |

| 8 What are the long lasting changes (cellular and molecular) in the brain vasculature and their potential consequences for functional outcome after TBI? |

| 9 Do potential changes in the brain vasculature after TBI affect long-term (months? years?) behavioral outcome after the initial impact? |

Figure 3.

The schematic illustration describes the evolution of injury after TBI. The acute phase (blue box) after the primary injury has been largely studied for vascular dysfunction: with hypo-perfusion, hypo-metabolism and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. These changes have a direct consequence on neuronal cell death. The consequences of TBI on neuronal survival have been well documented.

The question addressed here is: how do cerebral blood vessels recover in the long-term after traumatic brain injury? Clinical reports have demonstrated brain perfusion dysfunction at long-term after TBI (orange box). In jTBI, several changes in endothelial proteins (P-gp, Cav-1, claudin-5) have been observed up to two months post-TBI, suggesting a phenotypic transformation in the endothelium. Early vascular dysfunction (blue box) is still ongoing for several months/years after the primary injury and contributes to decreased blood flow, metabolism and pathological BBB. These cerebrovascular changes are possibly contributing to the absence of recovery in cognitive functions and some neurodegenerative processes observed in TBI patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dane Sorensen for critical review of the manuscript and David Ajao for tissue staining of Cav-1. Supported in part by the NIH R01HD061946 (JB).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Jerome Badaut and Gregory Bix declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

References

- 1.Zhang JH, Badaut J, Tang J, Obenaus A, Hartman R, Pearce WJ. The vascular neural network-a new paradigm in stroke pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(12):711–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronado VG, Xu L, Basavaraju SV, McGuire LC, Wald MM, Faul MD, et al. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury-related deaths--United States, 1997–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(5):1–32. ss6005a1 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurman D, Guerrero J. Trends in hospitalization associated with traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 1999;282(10):954–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.954. joc91173 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pop V, Badaut J. A Neurovascular Perspective for Long-Term Changes After Brain Trauma. Translational stroke research. 2011;2(4):533–45. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0126-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith DH, Uryu K, Saatman KE, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Protein accumulation in traumatic brain injury. Neuromolecular Med. 2003;4(1–2):59–72. doi: 10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:59. NMM:4:1-2:59 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavett BE, Stern RA, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC. Mild traumatic brain injury: a risk factor for neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010;2(3):18. doi: 10.1186/alzrt42. alzrt42 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-beta pathology: a link to Alzheimer’s disease? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(5):361–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2808. nrn2808 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponsford J, Willmott C, Rothwell A, Cameron P, Ayton G, Nelms R, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcome following mild traumatic head injury in children. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(4):360–72. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponsford J, Willmott C, Rothwell A, Cameron P, Ayton G, Nelms R, et al. Impact of early intervention on outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(6):1297–303. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1297. 108/6/1297 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponsford J, Cameron P, Fitzgerald M, Grant M, Mikocka-Walus A. Long-term outcomes after uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injury: a comparison with trauma controls. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(6):937–46. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lippert-Gruner M, Kuchta J, Hellmich M, Klug N. Neurobehavioural deficits after severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) Brain Inj. 2006;20(6):569–74. doi: 10.1080/02699050600664467. M8U8323711Q16J0U [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babikian T, Satz P, Zaucha K, Light R, Lewis RS, Asarnow RF. The UCLA Longitudinal Study of Neurocognitive Outcomes Following Mild Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000907. S1355617711000907 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD, Jr, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0. S0140-6736(09)61558-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneier AJ, Shields BJ, Hostetler SG, Xiang H, Smith GA. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury and associated hospital resource utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):483–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown AW, Leibson CL, Malec JF, Perkins PK, Diehl NN, Larson DR. Long-term survival after traumatic brain injury: a population-based analysis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19(1):37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison-Felix C, Whiteneck G, DeVivo M, Hammond FM, Jha A. Mortality following rehabilitation in the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems of Care. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19(1):45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himanen L, Portin R, Hamalainen P, Hurme S, Hiekkanen H, Tenovuo O. Risk factors for reduced survival after traumatic brain injury: a 30-year follow-up study. Brain Inj. 2011;25(5):443–52. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.556580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(7):709–35. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita M, Wei EP, Povlishock JT. Intensity- and interval-specific repetitive traumatic brain injury can evoke both axonal and microvascular damage. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(12):2172–80. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart J, Jr, Kraut MA, Womack KB, Strain J, Didehbani N, Bartz E, et al. Neuroimaging of cognitive dysfunction and depression in aging retired National Football League players: a cross-sectional study. JAMA neurology. 2013;70(3):326–35. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner A, Iverson GL, Stanwell P. A Systematic Review of Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Sport-Related Concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2013 doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner A, Iverson GL, McCrory P. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in sport: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satz P. Brain reserve capacity on symptom onset after brain injury: A formulation and review of evidence for threshold theory. Neuropsychology. 1993;7(3):273–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikonomovic MD, Uryu K, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, et al. Alzheimer’s pathology in human temporal cortex surgically excised after severe brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2004;190(1):192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.011. S0014488604002420 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeKosky ST, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Paljug WR, Wisniewski SR, Clark RS, et al. Association of increased cortical soluble abeta42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(4):541–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.541. 64/4/541 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine B, Kovacevic N, Nica EI, Cheung G, Gao F, Schwartz ML, et al. The Toronto traumatic brain injury study: injury severity and quantified MRI. Neurology. 2008;70(10):771–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304108.32283.aa. 70/10/771 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragan DK, McKinstry R, Benzinger T, Leonard J, Pineda JA. Depression of whole-brain oxygen extraction fraction is associated with poor outcome in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(2):199–204. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen Z, Bonvento G, Lacombe P, Hamel E. Serotonin in the regulation of brain microcirculation. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50(4):335–62. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamel E. Perivascular nerves and the regulation of cerebrovascular tone. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(3):1059–64. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00954.2005. 100/3/1059 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cauli B, Hamel E. Revisiting the role of neurons in neurovascular coupling. Frontiers in neuroenergetics. 2010;2:9. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(1):41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030. S0969-9961(09)00208-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverberg GD, Messier AA, Miller MC, Machan JT, Majmudar SS, Stopa EG, et al. Amyloid efflux transporter expression at the blood-brain barrier declines in normal aging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(10):1034–43. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181f46e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg GD, Miller MC, Machan JT, Johanson CE, Caralopoulos IN, Pascale CL, et al. Amyloid and Tau accumulate in the brains of aged hydrocephalic rats. Brain Res. 2010;1317:286–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.065. S0006-8993(09)02763-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge S, Song L, Pachter JS. Where is the blood-brain barrier … really? J Neurosci Res. 2005;79(4):421–7. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virgintino D, Robertson D, Errede M, Benagiano V, Tauer U, Roncali L, et al. Expression of caveolin-1 in human brain microvessels. Neuroscience. 2002;115(1):145–52. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00374-3. S0306452202003743 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogelgesang S, Warzok RW, Cascorbi I, Kunert-Keil C, Schroeder E, Kroemer HK, et al. The role of P-glycoprotein in cerebral amyloid angiopathy; implications for the early pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2004;1(2):121–5. doi: 10.2174/1567205043332225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruderisch N, Virgintino D, Makrides V, Verrey F. Differential axial localization along the mouse brain vascular tree of luminal sodium-dependent glutamine transporters Snat1 and Snat3. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(7):1637–47. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saubamea B, Cochois-Guegan V, Cisternino S, Scherrmann JM. Heterogeneity in the rat brain vasculature revealed by quantitative confocal analysis of endothelial barrier antigen and P-glycoprotein expression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(1):81–92. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badaut J, Nehlig A, Verbavatz J, Stoeckel M, Freund-Mercier MJ, Lasbennes F. Hypervascularization in the magnocellular nuclei of the rat hypothalamus: relationship with the distribution of aquaporin-4 and markers of energy metabolism. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12(10):960–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.del Zoppo GJ, Milner R. Integrin-matrix interactions in the cerebral microvasculature. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2006;26(9):1966–75. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000232525.65682.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baeten KM, Akassoglou K. Extracellular matrix and matrix receptors in blood-brain barrier formation and stroke. Developmental neurobiology. 2011;71(11):1018–39. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berardi N, Pizzorusso T, Maffei L. Extracellular matrix and visual cortical plasticity: freeing the synapse. Neuron. 2004;44(6):905–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dityatev A, Schachner M. Extracellular matrix molecules and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(6):456–68. doi: 10.1038/nrn1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milner R, Campbell IL. Developmental regulation of beta1 integrins during angiogenesis in the central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20(4):616–26. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owens T, Bechmann I, Engelhardt B. Perivascular spaces and the two steps to neuroinflammation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(12):1113–21. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818f9ca8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim YS, Kim SS, Cho JJ, Choi DH, Hwang O, Shin DH, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3: a novel signaling proteinase from apoptotic neuronal cells that activates microglia. J Neurosci. 2005;25(14):3701–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4346-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rafols JA, Kreipke CW, Petrov T. Alterations in cerebral cortex microvessels and the microcirculation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury: a correlative EM and laser Doppler flowmetry study. Neurol Res. 2007;29(4):339–47. doi: 10.1179/016164107X204648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badaut J, Moro V, Seylaz J, Lasbennes F. Distribution of muscarinic receptors on the endothelium of cortical vessels in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1997;778(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00999-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander MR, Owens GK. Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:13–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111(25):3481–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(3):957–89. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li DY, Brooke B, Davis EC, Mecham RP, Sorensen LK, Boak BB, et al. Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature. 1998;393(6682):276–80. doi: 10.1038/30522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Owens GK. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 1995;75(3):487–517. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rensen SS, Doevendans PA, van Eys GJ. Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2007;15(3):100–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03085963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hubbell MC, Semotiuk AJ, Thorpe RB, Adeoye OO, Butler SM, Williams JM, et al. Chronic Hypoxia and VEGF differentially modulate abundance and organization of Myosin Heavy Chain isoforms in Fetal and Adult Ovine Arteries. Am J Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00408.2011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baethmann A, Maier-Hauff K, Kempski O, Unterberg A, Wahl M, Schurer L. Mediators of brain edema and secondary brain damage. Crit Care Med. 1988;16(10):972–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198810000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sahuquillo J, Poca MA, Amoros S. Current aspects of pathophysiology and cell dysfunction after severe head injury. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7(15):1475–503. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaetz M. The neurophysiology of brain injury. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(1):4–18. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00258-x. S138824570300258X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zweckberger K, Eros C, Zimmermann R, Kim SW, Engel D, Plesnila N. Effect of early and delayed decompressive craniectomy on secondary brain damage after controlled cortical impact in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(7):1083–93. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(1):4–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. 99/1/4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bouma GJ, Muizelaar JP, Choi SC, Newlon PG, Young HF. Cerebral circulation and metabolism after severe traumatic brain injury: the elusive role of ischemia. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(5):685–93. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.5.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bryan RM, Jr, Cherian L, Robertson C. Regional cerebral blood flow after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. Anesth Analg. 1995;80(4):687–95. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Engel DC, Mies G, Terpolilli NA, Trabold R, Loch A, De Zeeuw CI, et al. Changes of cerebral blood flow during the secondary expansion of a cortical contusion assessed by 14C-iodoantipyrine autoradiography in mice using a non-invasive protocol. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(7):739–53. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kochanek PM, Marion DW, Zhang W, Schiding JK, White M, Palmer AM, et al. Severe controlled cortical impact in rats: assessment of cerebral edema, blood flow, and contusion volume. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12(6):1015–25. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schroder ML, Muizelaar JP, Bullock MR, Salvant JB, Povlishock JT. Focal ischemia due to traumatic contusions documented by stable xenon-CT and ultrastructural studies. J Neurosurg. 1995;82(6):966–71. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alford PW, Dabiri BE, Goss JA, Hemphill MA, Brigham MD, Parker KK. Blast-induced phenotypic switching in cerebral vasospasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(31):12705–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105860108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sahuquillo J, Munar F, Baguena M, Poca MA, Pedraza S, Rodriguez-Baeza A. Evaluation of cerebrovascular CO2-reactivity and autoregulation in patients with post-traumatic diffuse brain swelling (diffuse injury III) Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:233–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6475-4_67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vavilala MS, Muangman S, Tontisirin N, Fisk D, Roscigno C, Mitchell P, et al. Impaired cerebral autoregulation and 6-month outcome in children with severe traumatic brain injury: preliminary findings. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(4–5):348–53. doi: 10.1159/000094161. 94161 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muizelaar JP. The use of electroencephalography and brain protection during operation for basilar aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1989;25(6):899–903. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muizelaar JP, Ward JD, Marmarou A, Newlon PG, Wachi A. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in severely head-injured children. Part 2: Autoregulation. J Neurosurg. 1989;71(1):72–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.1.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Freeman SS, Udomphorn Y, Armstead WM, Fisk DM, Vavilala MS. Young age as a risk factor for impaired cerebral autoregulation after moderate to severe pediatric traumatic brain injury. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):588–95. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816725d7. 00000542-200804000-00009 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharples PM, Stuart AG, Matthews DS, Aynsley-Green A, Eyre JA. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in children with severe head injury. Part 1: Relation to age, Glasgow coma score, outcome, intracranial pressure, and time after injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(2):145–52. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharples PM, Matthews DS, Eyre JA. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in children with severe head injuries. Part 2: Cerebrovascular resistance and its determinants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(2):153–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Armstead WM. Cerebral hemodynamics after traumatic brain injury of immature brain. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1999;51(2):137–42. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(99)80087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ashwal S, Holshouser BA, Shu SK, Simmons PL, Perkin RM, Tomasi LG, et al. Predictive value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in pediatric closed head injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23(2):114–25. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00176-4. S0887-8994(00)00176-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bartnik BL, Sutton RL, Fukushima M, Harris NG, Hovda DA, Lee SM. Upregulation of pentose phosphate pathway and preservation of tricarboxylic acid cycle flux after experimental brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22(10):1052–65. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Casey PA, McKenna MC, Fiskum G, Saraswati M, Robertson CL. Early and sustained alterations in cerebral metabolism after traumatic brain injury in immature rats. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(6):603–14. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ashwal S, Holshouser B, Tong K, Serna T, Osterdock R, Gross M, et al. Proton MR spectroscopy detected glutamate/glutamine is increased in children with traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(11):1539–52. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Armstead WM. Age-dependent impairment of K(ATP) channel function following brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16(5):391–402. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wada K, Chatzipanteli K, Busto R, Dietrich WD. Role of nitric oxide in traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):807–18. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.5.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cherian L, Hlatky R, Robertson CS. Nitric oxide in traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(2):195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Armstead WM, Raghupathi R. Endothelin and the neurovascular unit in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Neurol Res. 2011;33(2):127–32. doi: 10.1179/016164111X12881719352138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hall ED, Wang JA, Miller DM. Relationship of nitric oxide synthase induction to peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative damage during the first week after experimental traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2012;238(2):176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hlatky R, Lui H, Cherian L, Goodman JC, O’Brien WE, Contant CF, et al. The role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the cerebral hemodynamics after controlled cortical impact injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20(10):995–1006. doi: 10.1089/089771503770195849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cherian L, Chacko G, Goodman C, Robertson CS. Neuroprotective effects of L-arginine administration after cortical impact injury in rats: dose response and time window. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304(2):617–23. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Orihara Y, Ikematsu K, Tsuda R, Nakasono I. Induction of nitric oxide synthase by traumatic brain injury. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;123(2–3):142–9. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00537-0. S0379073801005370 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steiner J, Rafols D, Park HK, Katar MS, Rafols JA, Petrov T. Attenuation of iNOS mRNA exacerbates hypoperfusion and upregulates endothelin-1 expression in hippocampus and cortex after brain trauma. Nitric Oxide. 2004;10(3):162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.03.005. S1089860304000552 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(13):6954–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xia Y, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(40):25804–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guix FX, Uribesalgo I, Coma M, Munoz FJ. The physiology and pathophysiology of nitric oxide in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76(2):126–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.001. S0301-0082(05)00064-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gu Y, Zheng G, Xu M, Li Y, Chen X, Zhu W, et al. Caveolin-1 regulates nitric oxide-mediated matrix metalloproteinases activity and blood-brain barrier permeability in focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Neurochem. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dore-Duffy P, Wang S, Mehedi A, Katyshev V, Cleary K, Tapper A, et al. Pericyte-mediated vasoconstriction underlies TBI-induced hypoperfusion. Neurol Res. 2011;33(2):176–86. doi: 10.1179/016164111X12881719352372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kreipke CW, Rafols JA. Calponin control of cerebrovascular reactivity: therapeutic implications in brain trauma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(2):262–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Plesnila N, Friedrich D, Eriskat J, Baethmann A, Stoffel M. Relative cerebral blood flow during the secondary expansion of a cortical lesion in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;345(2):85–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00396-3. S0304394003003963 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Armstead WM. Brain injury impairs ATP-sensitive K+ channel function in piglet cerebral arteries. Stroke. 1997;28(11):2273–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2273. discussion 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kontos HA, Wei EP. Endothelium-dependent responses after experimental brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9(4):349–54. doi: 10.1089/neu.1992.9.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ueda Y, Walker SA, Povlishock JT. Perivascular nerve damage in the cerebral circulation following traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(1):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sercombe R, Dinh YR, Gomis P. Cerebrovascular inflammation following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;88(3):227–49. doi: 10.1254/jjp.88.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang X, Jung J, Asahi M, Chwang W, Russo L, Moskowitz MA, et al. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on morphological and motor outcomes after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):7037–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-07037.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang H, Adwanikar H, Werb Z, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Matrix metalloproteinases and neurotrauma: evolving roles in injury and reparative processes. Neuroscientist. 2010;16(2):156–70. doi: 10.1177/1073858409355830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sifringer M, Stefovska V, Zentner I, Hansen B, Stepulak A, Knaute C, et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in infant traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25(3):526–35. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roberts DJ, Jenne CN, Leger C, Kramer AH, Gallagher CN, Todd S, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of the Temporal Matrix Metalloproteinase Response After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. J Neurotrauma. 2013 doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Suehiro E, Fujisawa H, Akimura T, Ishihara H, Kajiwara K, Kato S, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 in blood in association with activation of interleukin-6 after traumatic brain injury: influence of hypothermic therapy. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(12):1706–11. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Beaumont A, Fatouros P, Gennarelli T, Corwin F, Marmarou A. Bolus tracer delivery measured by MRI confirms edema without blood-brain barrier permeability in diffuse traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006;96:171–4. doi: 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nag S, Venugopalan R, Stewart DJ. Increased caveolin-1 expression precedes decreased expression of occludin and claudin-5 during blood-brain barrier breakdown. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(5):459–69. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pierre K, Pellerin L. Monocarboxylate transporters in the central nervous system: distribution, regulation and function. J Neurochem. 2005;94(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Prins ML, Giza CC. Induction of monocarboxylate transporter 2 expression and ketone transport following traumatic brain injury in juvenile and adult rats. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(4–5):447–56. doi: 10.1159/000094170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Appelberg KS, Hovda DA, Prins ML. The effects of a ketogenic diet on behavioral outcome after controlled cortical impact injury in the juvenile and adult rat. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(4):497–506. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wei EP, Hamm RJ, Baranova AI, Povlishock JT. The long-term microvascular and behavioral consequences of experimental traumatic brain injury after hypothermic intervention. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(4):527–37. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abrahamson EE, Foley LM, Dekosky ST, Kevin Hitchens T, Ho C, Kochanek PM, et al. Cerebral blood flow changes after brain injury in human amyloid-beta knock-in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(6):826–33. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Neuwelt E, Abbott NJ, Abrey L, Banks WA, Blakley B, Davis T, et al. Strategies to advance translational research into brain barriers. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):84–96. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70326-5. S1474-4422(07)70326-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Neuwelt EA, Bauer B, Fahlke C, Fricker G, Iadecola C, Janigro D, et al. Engaging neuroscience to advance translational research in brain barrier biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(3):169–82. doi: 10.1038/nrn2995. nrn2995 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Strbian D, Durukan A, Pitkonen M, Marinkovic I, Tatlisumak E, Pedrono E, et al. The blood-brain barrier is continuously open for several weeks following transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2008;153(1):175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pop V, Sorensen DW, Kamper JE, Ajao DO, Murphy MP, Head E, et al. Early brain injury alters the blood-brain barrier phenotype in parallel with beta-amyloid and cognitive changes in adulthood. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(2):205–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lin JL, Huang YH, Shen YC, Huang HC, Liu PH. Ascorbic acid prevents blood-brain barrier disruption and sensory deficit caused by sustained compression of primary somatosensory cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(6):1121–36. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.277. jcbfm2009277 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cirrito JR, Deane R, Fagan AM, Spinner ML, Parsadanian M, Finn MB, et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3285–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330(6012):1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. science.1197623 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zlokovic BV. Neurodegeneration and the neurovascular unit. Nat Med. 2010;16(12):1370–1. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1370. nm1210-1370 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jodoin J, Demeule M, Fenart L, Cecchelli R, Farmer S, Linton KJ, et al. P-glycoprotein in blood-brain barrier endothelial cells: interaction and oligomerization with caveolins. J Neurochem. 2003;87(4):1010–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Predescu D, Palade GE. Plasmalemmal vesicles represent the large pore system of continuous microvascular endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(2 Pt 2):H725–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lisanti MP, Scherer PE, Tang Z, Sargiacomo M. Caveolae, caveolin and caveolin-rich membrane domains: a signalling hypothesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4(7):231–5. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90114-7. 0962892494901147 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bucci M, Gratton JP, Rudic RD, Acevedo L, Roviezzo F, Cirino G, et al. In vivo delivery of the caveolin-1 scaffolding domain inhibits nitric oxide synthesis and reduces inflammation. Nat Med. 2000;6(12):1362–7. doi: 10.1038/82176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bauer PM, Yu J, Chen Y, Hickey R, Bernatchez PN, Looft-Wilson R, et al. Endothelial-specific expression of caveolin-1 impairs microvascular permeability and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(1):204–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406092102. 0406092102 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lajoie P, Goetz JG, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(3):381–5. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. jcb.200811059 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nag S, Manias JL, Stewart DJ. Expression of endothelial phosphorylated caveolin-1 is increased in brain injury. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009;35(4):417–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2008.01009.x. NAN1009 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McCaffrey G, Staatz WD, Quigley CA, Nametz N, Seelbach MJ, Campos CR, et al. Tight junctions contain oligomeric protein assembly critical for maintaining blood-brain barrier integrity in vivo. J Neurochem. 2007;103(6):2540–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04943.x. JNC4943 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.McCaffrey G, Staatz WD, Sanchez-Covarrubias L, Finch JD, Demarco K, Laracuente ML, et al. P-glycoprotein trafficking at the blood-brain barrier altered by peripheral inflammatory hyperalgesia. J Neurochem. 2012;122(5):962–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mellergard P, Sjogren F, Hillman J. Release of VEGF and FGF in the extracellular space following severe subarachnoidal haemorrhage or traumatic head injury in humans. Br J Neurosurg. 2010;24(3):261–7. doi: 10.3109/02688690903521605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Morgan R, Kreipke CW, Roberts G, Bagchi M, Rafols JA. Neovascularization following traumatic brain injury: possible evidence for both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Neurol Res. 2007;29(4):375–81. doi: 10.1179/016164107X204693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]