Abstract

The etiologic agent of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), Machupo virus (MACV) is reported to have a mortality rate of 25 to 35%. First identified in 1959, BHF was the cause of a localized outbreak in San Joaquin until rodent population controls were implemented in 1964. The rodent Calomys collosus was identified as the primary vector and reservoir for the virus. Multiple animal models were considered during the 1970’s with the most human-like disease identified in Rhesus macaques but minimal characterization of the pathogenesis has been published since. A reemergence of reported BHF cases has been reported in recent years, which necessitates the further study and development of a vaccine to prevent future outbreaks.

Introduction

Machupo virus (MACV) is the etiological agent of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF) [1, 2] and a member of the family Arenaviridae [3–9]. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever was first described in human patients in the Beni district of northeast Bolivia near the city of San Joaquin during an outbreak which lasted from 1959 to 1963. A team of doctors from the Middle American Research Unit (MARU), led by Dr. Karl Johnson, were the first western investigators to identify and characterize BHF in humans [10–12]. The prototypical strain of MACV, Carvallo, was isolated from the spleen of a lethal human case following serial passage in young hamsters [1, 13]. Current research with MACV is limited as it is classified as a Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Select Agent and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) category A pathogen requiring a biosafety level (BSL)-4 laboratory for research within the United States [14]. With the reemergence of BHF cases in the Beni district and the construction of the interoceanic highway along northern Bolivia, the public health threat to the region must be addressed prior to another major outbreak.

Arenaviridae Genome

Members of the Arenaviridae family are enveloped, bi-segmented, negative-sense RNA viruses [15]. The virions are pleomorphic when viewed by electron microscopy and the name Arenaviridae is derived from the ‘sandy’ appearance caused by cellular ribosomes found within the virion [16]. The long (L) segment (~7.2kb) encodes two viral proteins: the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (L protein) [17, 18] and a RING finger protein (Z), the arenavirus equivalent to a matrix protein [19–23]. The short (S) segment (~3.3kb) encodes two viral proteins: the viral glycoprotein precursor (GPC) and the nucleoprotein (NP). The GPC is post-translationally cleaved in two steps, the first by cellular signal peptidase to generate the stable signal peptide (SSP) and second by SKI-1/S1P subtilase into two glycoproteins, GP-1 and GP-2 [24–29]. The SSP is myristoylated following cleavage and is necessary for the transport of the GP-1/2 polypeptide from the endoplasmic reticulum to the golgi and for trafficking of the GP-1 and 2 proteins to the cellular membrane prior to virion budding [28, 30]. The viral spike is comprised of a globular head formed by the GP-1 while GP-2 is bound in the lipid bilayer of the cellular membrane anchoring GP-1 to the viral particle [15, 31]. NP is the most common viral protein produced during MACV infection and is the primary structural protein in the viral nucleocapsid [15].

Both the S and L segments utilize an ambisense genomic encoding strategy with two open reading frames (ORFs), one for each protein, in opposite directions. The ORFs of both segments are separated by an intergenic region (IGR). The IGRs are predicted to form secondary RNA structures, which are necessary for terminating the replication of the MACV template [32, 33]. At the each end of the L and S segments are untranslated regions (UTRs) of which, the terminal 17–19 nucleotides are highly conserved within the Arenaviridae family [15, 34, 35]. These conserved termini regions are reported to be vital in segment pan-handle formation for viral template replication and transcription [15, 36, 37].

Geographic Distribution and Epidemiology of Machupo Virus

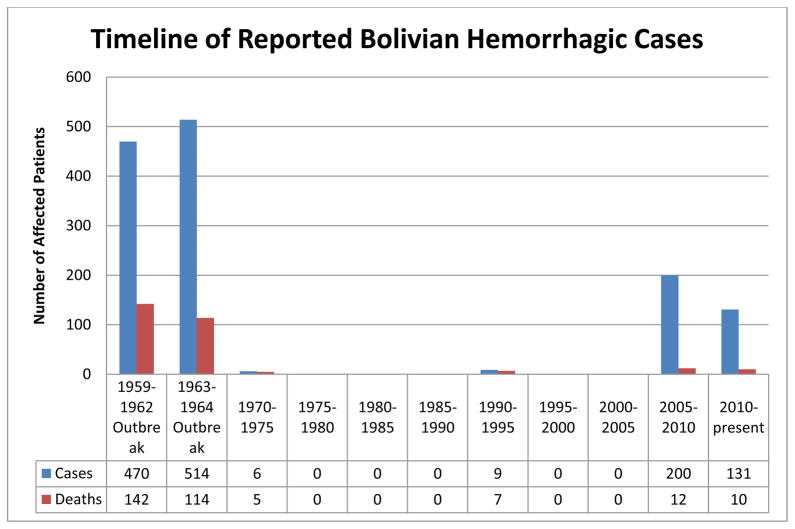

The first outbreak of MACV was reported in Bolivia between 1959 and 1964. Between 1976 and 1993 there were no reported cases of BHF, potentially due to implementation of rodent control measures in the populated urban areas or through under reporting of disease within the region. A limited number of cases and deaths were reported in the mid-1990s including a familial outbreak resulting in 6 infections. Recently, an increase in the number of cases has been reported annually starting in 2006 with a peak of reported cases in 2008 [1, 38–43] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Reported cases and deaths caused by MACV from the original outbreak to July of 2013. An increase in reported cases has occurred since 2007.

During the 1959 outbreak, researchers identified Calomys callosus [2], the large vesper mouse, as the most likely natural vector and reservoir for MACV. C. callosus has a wide natural geographical range including portions of Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina [44]. While C. callosus are found throughout many countries of South America, MACV is endemic within only a small geographic region of Bolivia (Fig. 2). This region of endemic MACV corresponds with the same geographic region in which a specific monophyletic linage of C. callosus is found [45]. The same phenomenon of a single rodent reservoir is reported with other arenaviruses [46–49].

Figure 2.

Map of Bolivia. A map identifying different important locations within Bolivia. 1) The city of Magdalena which was a site of a limited number of cases in 1994. 2) City of San Joaquin and surrounding areas, the site of the original 1959–1964 outbreak. 3) City of San Ramón, where 3 cases were identified in 1993 and 2008. 4) The capital of Bolivia, La Paz. The green line running west to east in the north of the map represents the path of the interoceanic highway completed in 2012. The red oval encompasses the region in which endemic MACV cases have been reported. The yellow oval represents the region in Bolivia the natural reservoir, C. collosus, is found.

The infectivity rate of captured and necropsied C. callosus animals has ranged from 11% to 80% [2, 42, 50]. Laboratory testing showed that nearly 100% of neonatal (>3 days) C. callosus challenged IP with MACV become persistently infected with detectable viremia and viral shedding from the urine and saliva of the animals. These animals developed no reported disease and never developed neutralizing antibodies against MACV [51]. Older (>2 weeks) C. callosus challenged IP with MACV were shown to develop two distinct responses to infection. One group continued to have detectable viremia and shedding from the urine and saliva with no neutralizing antibody development while the other group developed neutralizing antibodies at 4 weeks post infection which corresponded with a decrease in detectable viremia and virus in the urine and saliva. The first group was shown to develop anemia and reduced fertility when compared to the neonate groups [51–53].

The route of spread of MACV from C. callosus to humans is believed to be similar to other South American hemorrhagic arenaviruses; through breathing in aerosolized excreta or secreta from the rodent reservoir, consumption of contaminated food, or through direct mucus membrane contact with infectious particles [12, 15]. Nosocomial transmission has been reported in BHF cases when family members visiting ill patients developed BHF [54, 55]. Further evidence of human to human transmission occurred in 1971 when four secondary cases of BHF were identified in hospital workers following close contact with a patient suffering from BHF [56]. Clinical evidence supports the nosocomial spread of MACV however the epidemiologic evidence does not support this form of transmission as a method for maintaining an epidemic [10].

In the first two to three years of the 1959 outbreak, most of the cases were in male adults in the rural areas around San Joaquin. The reason for the high male case rate is suspected to be due to the ratio of male-to-female working in the fields. In 1962 an increase in the number of urban cases was correlated to a decrease in the domestic feline population [10] and an increase in the rodent populations within the town. The drop in feline population is suspected to have been caused by an over exposure to DDT and not due to infection from MACV. Control of the outbreak was accomplished by 1965 following identification of the rodent reservoir and initiation of a systematic trapping of rodents including the importation of a feline population [12, 52]. The cases reported in 1994 were also initially identified within a single family unit in which the primary case was a rural worker [39] and the recent cases have also been linked closely to rural/agricultural exposures [38]. All of the recent reported cases of BHF have originated in the Beni district of Bolivia (Fig. 2).

Clinical Manifestations of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

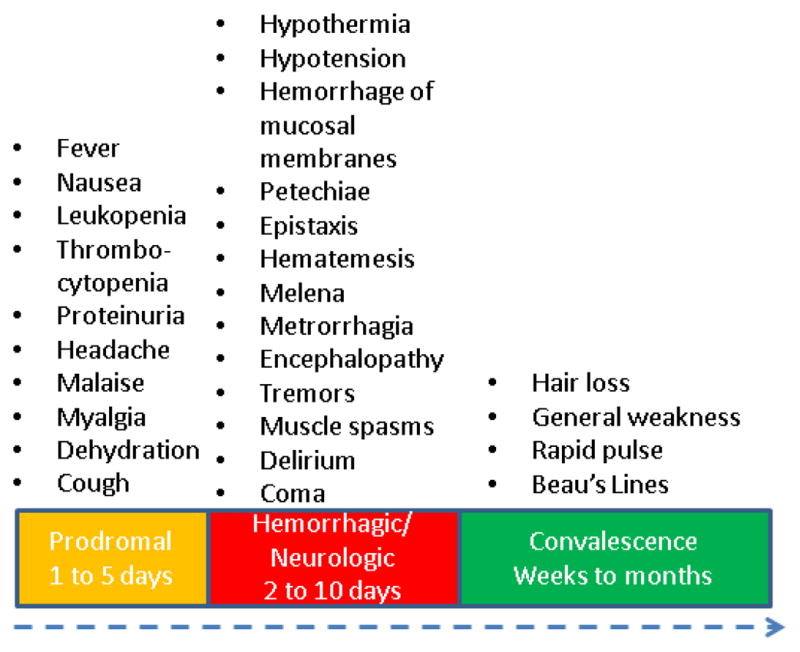

Following aerosol exposure virus particles are likely engulfed by alveolar macrophages leading to the first cellular infection [57]. The incubation period for BHF is 3 to 16 days following exposure [58]. Previously, exposure was believed to consistently lead to disease development as there were a low number of serum samples collected with antibodies specific to BHF who did not report disease development during the 1959 to 1964 outbreak [10]. Recent serum sampling has detected a number of people with detectable IgG antibodies who never reported disease manifestations similar to BHF. These unpublished samplings may imply a number of possibilities; the first that MACV may be less lethal than identified in the initial outbreak, that MACV may be more widespread than previously thought within the Beni district, or that MACV virulence has reduced since the original outbreak in the 1960s [15]. The prodromal phase of BHF is similar to that of Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF) caused by Junin virus (JUNV), with the onset of fever, malaise, myalgia, headache, and anorexia. This develops into severe symptoms including vomiting, hypersensitivity, and early signs of vascular damage. Laboratory findings of clinical samples include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and proteinuria during the first few days following hospitalization [12, 15, 55, 58] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Clinical disease progression in human cases of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Human disease is biphasic with symptoms first identified in the prodromal phase which include general illness and flu-like symptoms. One third of patients enter a hemorrhagic/neurologic phase where the most severe symptoms are identified including hemorrhage and coma. Survivors enter a convalescent stage, which can last weeks to months.

Approximately one third of patients develop severe neurological or hemorrhagic symptoms within a week of the prodromal phase. Symptoms include flushing of the head and torso, petechiae, hypotension, blood in vomit and stool, delirium, convulsions, tremors, bleeding gums, coma, and death [59]. The mortality rate varies between outbreaks of BHF but is estimated to be around 25% [15]. The convalescent phase can last up to eight weeks and can include fatigue, dizziness and hair loss. The cause of these neurological issues is currently unknown. The effectiveness of immune serum treatment with non-human primates following exposure to MACV implies clearance is mediated through a humoral immune response. This is different from what has been identified in the Old World arenavirus Lassa virus (LASV), the etiological agent of Lassa fever (LASF), which research has identified the importance of a cellular response in protection [60, 61].

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care for Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

Identification of MACV infection can be accomplished in the late stages of the prodromal phase utilizing an enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) of both IgM and IgG [15]. Diagnostic reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests are also available for quick and accurate identification of the presence of MACV RNA but the kit and equipment is only available at larger hospitals and laboratories in Bolivia. Virus isolation from blood and tissue samples can also be utilized to identify virus infection however, there are several drawback including the length of time and required personal protection equipment (PPE).

Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved vaccines or therapeutics for BHF. During the 1959 outbreak, supportive care and proper administration of fluids were the best available treatment options for patients in Bolivia [55]. Following isolation of MACV, the use of convalescent immune plasma from survivors has been utilized in a similar manner as treatment for Argentine hemorrhagic fever [62]. Researchers have identified the administration of human immunoglobulin against MACV was protective in rhesus monkeys when given at four hours before or after challenge [63], however, no clinical trials have been completed in human patients. In the same study all primates receiving high doses of immunoglobulin developed a chronic, late neurological syndrome (LNS). Three of the four primates that developed signs of neurological impairment died weeks after clinical signs of acute BHF had abated. An additional study in non-human primates (NHPs) identified a lethal chronic neurological disease in rhesus monkeys in which six animals receiving convalescent serum succumbed to neurological disease following serum treatment [64]. The efficacy of ribavirin, an antiviral therapeutic shown to be effective against LASV [65], has been tested in a minimal number of human BHF cases. Due to the limited number of patients, no clinical trials have been performed to determine the effectiveness of therapeutics in humans [39, 66]. Preliminary reports also identified vaccination with Candid#1 (a vaccine against AHF) to be protective in NHPs against MACV but no further testing has been completed to confirm these findings in humans [67]. Recent studies in a knockout STAT-1 mouse model demonstrated a significant increase in survival with ribavirin treatment [68]. The lack of clinical infrastructure to support a national convalescent serum stock in Bolivia combined with no proven effective therapeutics or vaccines against MACV will make controlling future outbreaks of MACV difficult.

Animal Models for Machupo Virus

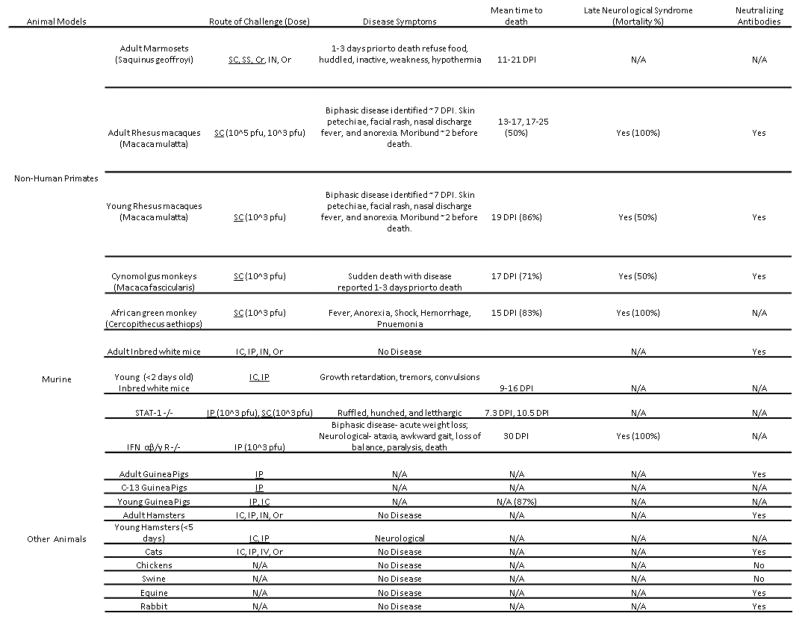

Animal models have provided most of the information currently available on MACV pathogenesis (Fig. 4). Unlike other arenaviruses, MACV was successfully controlled through the 1970’s to the early 1990’s through rodent reduction programs. The number of human cases which have been identified over the years with LASV and JUNV has been important in developing a clearer picture of disease progression and pathogenesis as well as providing key clinical isolates for study within the laboratory. This has not been possible with MACV, making the early NHP and other animal studies important in understanding BHF pathogenesis.

Figure 4.

Table of published animal models from the 1960s to present. When available, data of clinical development, routes of exposure, and doses are reported. Routes of exposure which are underlined represent lethal challenges. Acronyms: Sub-cutaneous (SC), Scarified skin (SS), Corneal instillation (Cr), Intra-nasal (IN), Oral (Or), Plaque forming unit (pfu), Intracranial (IC), Intravenous (IV), and intraperitoneal (IP).

Non-Human Primates

Four NHP species have been utilized in studying BHF disease pathogenesis. Adult marmosets (Saquinus geoffroyi) have been shown to develop a lethal infection following subcutaneous (SC) infection, scarified skin exposure, and corneal instillation but not through intranasal (IN) or oral administration of MACV [69]. The time until death in marmosets ranged from 11 to 21 days following SC infection and was dependent upon infection dose. Virus was successfully isolated from the brains, spleens, kidneys, heart, liver, saliva, and urine (1 sample) of animals which succumbed to disease [53]. Clinical development of disease appeared one to three days before death with symptom development including lethargy, weakness, and hypothermia.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) have been shown to develop a lethal infection following SC infection with MACV. Disease progression was described as bi-phasic, similar to human disease. Two studies, both utilizing adult and young rhesus macaques identified clinical illness developing five to six days post infection (DPI). Early symptoms included depression, fever, anorexia, diarrhea, facial rash, and conjunctivitis. Disease progression continued in all macaques with severely ill animals becoming moribund a day or two prior to death. In the first study, animals were infected with either 105 or 103 plaque forming units (pfu) of MACV, and the mean time to death (MTD) was 14.3 and 19.5 DPI respectively with a 100% case fatality rate [70]. A second report utilizing young (2.5–4kg) and adult (5–8kg) rhesus macaques resulted in mortality rates of 85% and 50% following infection with 103 pfu [71]. The MTD was similar as with the first study. Survivors developed late neurological disease 26 to 41 days after infection in which 66% of the surviving young macaques and all of the adult macaques succumbed to disease [71]. Histopathological examination of infected macaques identified moderate to severe encephalitis with vasculitis and internal hemorrhage. Following SC infection, 100% of cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) became viremic at five DPI. Minimal disease progression or clinical signs were identified throughout the study and death occurred suddenly in 70% of the animals. The MTD was similar to that of the rhesus monkey along with comparable LNS development with a 50% mortality rate [71].

MACV disease progression has also been studied in the African green monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops). Following SC infection, 100% of animals subjects succumbed to MACV infection, 83% to the acute infection and 17% to late neurological development [72]. Histopathological samples taken at the time of death identified necrosis and systemic hemorrhage in the kidneys, liver, and spleen of infected animals. Pneumonia was also identified during necropsies in all of the infected African green monkeys at the time of death. The clinical development of disease was biphasic, similar to that of the rhesus monkeys, but not cynomologus monkeys or adult marmosets.

Small Mammals

Adult small mammals have shown a strong resistance to MACV infection. Inbred adult mice (BALB/C, C3H/HCN, AKR, DBA/2, C57BL/6) challenged by the intracranial (IC) or intraperitoneal (IP) routes had no detectable viremia or illness but developed a strong neutralizing antibody response shown by plaque reducing neutralization test (PRNT). Young inbred mice, less than two days old, developed lethal disease following IC and IP challenge with MACV [54,70].

Adult hamsters when challenged IN or orally do not develop detectable illness. When infected through an IP or IC route at 1,000 pfu with MACV, adult hamsters developed detectable viremia but no observable signs of illness. Neutralizing and complement fixing antibodies are detected 30 days after IC and IP challenge in hamsters [53, 69]. Newborn hamsters (less than 6 days old) have been reported to develop a lethal infection following challenge IP, IC, or IN but there have been no published reports of disease development or characterization in these animals [53, 69].

A report utilizing STAT-1 knockout mice described the development of lethal disease following IP (MTD = 7.3 days, 100% mortality), SC (MTD=10 days, 66% mortality), and IN (MTD=20, 25% mortality). Virus was detected in the spleen, kidneys, serum, lung, and liver. Clinical development of disease including ruffled fur, hunched back, awkward gait, and lethargy were apparent at 5 DPI [68]. Young and suckling inbred mice also develop a lethal infection following challenge IP or IC but do not develop any hemorrhagic symptoms comparable to BHF described in humans or NHPs [53].

An additional mouse model utilizing interferon αβ/γ receptor knockout (IFN R αβ/γ −/−) mice has been reported to develop a lethal disease following challenge with MACV through an IP route of injection [73]. Animals were challenged with either wild type MACV or a recombinant MACV virus and were reported to develop two clinical phases of disease. From 10 to 14 DPI animals were reported to lose a significant percent of body weight when compared to uninfected animals. Starting at 22 DPI, animals developed neurological symptoms including ataxia, rear limb-paralysis, and an awkward gait. One to three days prior to death, infected animals had severe weight and body temperature loss with a MTD around 28 DPI.

Both outbred (Hartley) and inbred (C-13) species of adult guinea pigs have been reported to develop a lethal infection following challenge with MACV. The characterization of disease development in either species has not been reported [53, 56, 74]. There have been no reports utilizing young guinea pigs as an animal model. Other adult animals which have been shown to develop a detectable neutralizing antibody response but no disease are: horses, cats, rats, and other outbred wild mice species [69].

Conclusions

When compared to JUNV and LASV, there is very little published research on MACV. This is probably due to multiple factors including; the reported absence of BHF for nearly 20 years, the lack of any publicly available clinical samples from modern cases, the difficulty and remoteness of the region, and the geopolitical environment within Beni and Bolivia. In the more recent arenavirus papers, LASV and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), both Old World arenaviruses, and Tacaribe virus, a non-pathogenic New World arenavirus, are commonly utilized as prototypical arenaviruses. Describing LASV or LCMV as prototypical arenaviruses in place of MACV and JUNV, which both produce similar clinical disease, is not accurate due to the differences reported in the clinical diseases caused by the Old World and New World hemorrhagic arenaviruses.. For example, the early reports of strong interferon induction in NHPs following infection with MACV resulting in high systemic levels of this cytokine are highly comparable to that seen in human cases of AHF but not LASF [75, 76]. The efficacy of immunoglobulin in protecting NHPs from the acute infection also mirrors that of AHF instead of LASF [63, 77, 78]. The clinical similarities between BHF and AHF identify them as comparable diseases very distinct from reported clinical cases of LASF. Further research is necessary in identifying the distinct features of BHF disease development which may be useful in developing a better understanding of BHF and AHF.

There has been minimal research for the development of countermeasures or treatment for BHF. The utilization of ribavirin is dependent upon availability which may be extremely difficult in regions of Bolivia due to cost and cold storage requirements. Furthermore, the only reported efficacy studies had an extremely limited number of patients and lacked statistical significance. Similarly, the utilization of immunoglobulin has been proposed but unlike with AHF, there has been no identification of a treatment time frame in which it would be protective against BHF. In addition, 10% of patients receiving treatment with IgG against AHF develop a non-lethal form LNS, making immune serum an unsatisfactory long term treatment option without further understanding of LNS. The development and licensing of Candid#1, an attenuated vaccine strain of JUNV, in Argentina has greatly reduced the annual number of cases of AHF and utilization of the vaccine in endemic regions of Bolivia may reduce the chances for another large outbreak [79].

While initial control of the rodent reservoir for MACV appears to have been effective, completely eliminating BHF from the region during the late 70’s through the early 90’s, this absolute effectiveness is most likely inaccurate due to a failure of disease reporting. The increasing number of cases since the mid 90’s may represent either a sign of better disease reporting or a sign of the reemergence of MACV. In either case, BHF has been identified as a serious human disease of which there is very little modern human data or laboratory research available. Population and agricultural expansion in the region may lead to an increase in the number of cases as seen with AHF [80]. The increased number of farmers growing grain crops and subsequent rodent population booms in the pampas region of Argentina has been one of the potential causes of the expansion of JUNV, [81] which may occur as the Beni district further develops as an agricultural region. With the completion of the interoceanic highway connecting the Pacific and Atlantic overland trade routes through Brazil to Peru along the northern Bolivian border (Fig. 2), there is an increased risk of MACV leaving the endemic region and becoming an international threat through increased transport of food grains.

In conclusion, MACV causes a distinct disease from that of LASV and LCMV and while similar to JUNV, further research needs to be completed to confirm these similarities. The increase in reported cases of BHF implies a potential reemergence of MACV and, with increased trade and travel within the region, there is a greater possibility of spread, both through transport of the reservoir rodent and infected individuals, to other regions within Bolivia and potentially the world. More research and development of countermeasures must be initiated as the two primary options have had minimal reporting for efficacy and treatment timelines. Finally, while Candid#1 has been shown to be efficacious in NHPs, this may not translate to protection in humans. The development of a homologous vaccine designed specifically for MACV may ensure better protection to the local population along with a more ready acceptance by the local government for implementation of at-risk individuals.

Highlights.

A comprehensive review of the history of Machupo virus.

A review of the clinical disease Bolivian hemorrhagic fever.

A comprehensive review of animal models for the study of Machupo virus pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

*1 Report identifying the reemergence of MACV in the Beni district

**1 Best clinical description of four clinical cases of BHF from the original 1959 outbreak

*2 Report on the development of the first reverse genetics system for MACV and reports of a novel murine model for studying neurovirulence.

- 1.Webb PA. Properties of Machupo Virus. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1965;14(5):799–802. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson KM, et al. Isolation of Machupo Virus from Wild Rodent Calomys callosus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1966;15(1):103–106. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1966.15.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parodi AS, et al. Isolation of the Junin virus (epidemic hemorrhagic fever) from the mites of the epidemic area (Echinolaelaps echidninus, Barlese) Prensa Med Argent. 1959;46:2242–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terezinha Lisieux M Coimbra, et al. New arenavirus isolated in Brazil. Lancet. 1994;343(8894):391–392. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salas R, et al. Venezuelan haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1991;338(8774):1033–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado S, et al. Chapare Virus, a Newly Discovered Arenavirus Isolated from a Fatal Hemorrhagic Fever Case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(4):e1000047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley SM, Casals J. Lassa Fever, a New Virus Disease of Man from West Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1970;19(4):680–691. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briese T, et al. Genetic Detection and Characterization of Lujo Virus, a New Hemorrhagic Fever–Associated Arenavirus from Southern Africa. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000455. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulhorst CF, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Whitewater Arroyo Virus, a Novel North American Arenavirus. Virology. 1996;224(1):114–120. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenzie RB, et al. Epidemic Hemorrhagic Fever in Bolivia: I. A Preliminary Report of the Epidemiologic and Clinical Findings in a New Epidemic Area in South America. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1964;13(4):620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuns ML. Epidemiology of Machupo Virus Infection. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1965;14(5):813–816. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson KM. Epidemiology of Machupo Virus Infection. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1965;14(5):816–818. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson KM, et al. Virus Isolations from Human Cases of Hemorrhagic Fever in Bolivia. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, NY) 1965;118(1):113–118. doi: 10.3181/00379727-118-29772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Select Agents and Toxins List. 2013 Available from: http://www.selectagents.gov/Select%20Agents%20and%20Toxins%20List.html.

- 15.Buchmeier M, de la Torre J, Peters C. Arenaviridae: The Viruses and Their Replication. In: Knipe HP, editor. Field’s Virology. Wolter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2007. pp. 1791–1827. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy FA, et al. Arenoviruses in Vero Cells: Ultrastructural Studies. Journal of Virology. 1970;6(4):507–518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.4.507-518.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poch O, et al. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. Embo J. 1989;8(12):3867–74. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvato M, Shimomaye E, Oldstone MBA. The primary structure of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus L gene encodes a putative RNA polymerase. Virology. 1989;169(2):377–384. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez M, Craven RC, de la Torre JC. The small RING finger protein Z drives arenavirus budding: implications for antiviral strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(22):12978–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133782100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strecker T, et al. Lassa Virus Z Protein Is a Matrix Protein Sufficient for the Release of Virus-Like Particles. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(19):10700–10705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10700-10705.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djavani M, et al. Completion of the Lassa Fever Virus Sequence and Identification of a RING Finger Open Reading Frame at the L RNA 5′. End Virology. 1997;235(2):414–418. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvato MS, Shimomaye EM. The completed sequence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus reveals a unique RNA structure and a gene for a zinc finger protein. Virology. 1989;173(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salvato MS, et al. Biochemical and immunological evidence that the 11 kDa zinc-binding protein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is a structural component of the virus. Virus Research. 1992;22(3):185–198. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90050-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchmeier MJ, Oldstone MBA. Protein structure of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: Evidence for a cell-associated precursor of the virion glycopeptides. Virology. 1979;99(1):111–120. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyer WR, et al. Endoproteolytic Processing of the Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Glycoprotein by the Subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(5):2866–2872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2866-2872.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenz O, et al. The Lassa virus glycoprotein precursor GP-C is proteolytically processed by subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(22):12701–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221447598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.York J, Nunberg JH. Role of the stable signal peptide of Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein in pH-dependent membrane fusion. J Virol. 2006;80(15):7775–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00642-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.York J, et al. The signal peptide of the Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein is myristoylated and forms an essential subunit of the mature G1–G2 complex. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10783–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10783-10792.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.York J, Nunberg JH. Distinct requirements for signal peptidase processing and function in the stable signal peptide subunit of the Junin virus envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 2007;359(1):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eichler R, et al. Identification of Lassa virus glycoprotein signal peptide as a trans-acting maturation factor. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(11):1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riviere Y, et al. The S RNA segment of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus codes for the nucleoprotein and glycoproteins 1 and 2. Journal of Virology. 1985;53(3):966–968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.3.966-968.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tortorici MA, et al. Arenavirus nucleocapsid protein displays a transcriptional antitermination activity in vivo. Virus Res. 2001;73(1):41–55. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer BJ, Southern PJ. Sequence heterogeneity in the termini of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus genomic and antigenomic RNAs. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(11):7659–7664. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7659-7664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auperin DD, Compans RW, Bishop DHL. Nucleotide sequence conservation at the 3′ termini of the virion RNA species of new World and Old World arenaviruses. Virology. 1982;121(1):200–203. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auperin DD, McCormick JB. Nucleotide sequence of the Lassa virus (Josiah strain) S genome RNA and amino acid sequence comparison of the N and GPC proteins to other arenaviruses. Virology. 1989;168(2):421–425. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emonet SF, et al. Rescue From Cloned cDNAs And In Vivo Characterization of Recombinant Pathogenic Romero And Life-Attenuated Candid #1 Strains Of Junin Virus, The Causative Agent Of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever Disease. Journal of Virology. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02102-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kranzusch PJ, et al. Assembly of a functional Machupo virus polymerase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(46):20069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007152107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*1.Aguilar PVCW, Vargas J, Guevara C, Roca Y, Felices V, et al. Reemergence of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, 2007–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009 doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090017. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/9/1526.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Kilgore Paul E, CJP, Mills James N, Pierre LA, Rollin E, Khan Ali S, Ksiazek TG. Prospects for the Control of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1995 doi: 10.3201/eid0103.950308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ProMED-email. BOLIVIAN HEMORRHAGIC FEVER - BOLIVIA: (BENI) ProMED-email; 2013. 20130317.1590121. [Google Scholar]

- 41.ProMED-email. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever - Bolivia (02): (BE) ProMED-email; 2013. 20130420.1660132. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ProMED-mail. BOLIVIAN HEMORRHAGIC FEVER - BOLIVIA (05): (BENI) ProMED-mail; 2012. 20120730.1220842. [Google Scholar]

- 43.ProMED-email. BOLIVIAN HEMORRHAGIC FEVER - BOLIVIA (05): (BENI) ProMED-email; 2012. 20120730.1220842. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olds N. A revision of the genus Calomys (Rodentia: Muridae) City University of New York; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dragoo JW, et al. Relationships within the Calomys callosus species group based on amplified fragment length polymorphisms. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2002;31(2003):703–713. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabattini MS, et al. Infection natural y experimental de roedores con virus Junin. Medicina. 1977;37:149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabattini MS, Contigiani MS. Ecological and biological factors influencing the maintenance ofarenaviruses in nature, with special reference to the agent of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Acad Brasil Cienc. 1982:261–262. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kravetz F, et al. Distribution of Junin virus and its reservoirs: A tool for Argentine hemorrhagic fever risk evaluation in non-endemic areas. Interciencia. 1986;11:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salazar-Bravo J, Ruedas LA, Yates TL. Mammalian reservoirs of arenaviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;262:25–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Organization, P.A.H. Machupo Hemorrhagic Fever. Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. 2003;II [Google Scholar]

- 51.Justines G, Johnson KM. Immune Tolerance in Calomys callosus infected with Machupo Virus. Nature. 1969;222(5198):1090–1091. doi: 10.1038/2221090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson KM, et al. Chronic infection of rodents by Machupo virus. Science. 1965;150(3703):1618–9. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3703.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WEBB PA, JUSTINES G, JOHNSON KM. Infection of wild and laboratory animals with Machupo and Latino viruses. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(4–6):493–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douglas R, Wiebenga N, Couch R. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever probably transmitted by personal contact. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1965;82:8591. [Google Scholar]

- 55**1.Stinebaugh BJ, et al. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever: A report of four cases. The American journal of medicine. 1966;40(2):217–230. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(66)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.PETERS CJ, et al. HEMORRHAGIC FEVER IN COCHABAMBA, BOLIVIA, 1971. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1974;99(6):425–433. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKee KT, Jr, et al. Virus-specific factors in experimental Argentine hemorrhagic fever in rhesus macaques. J Med Virol. 1987;22(2):99–111. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890220202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers Caused by Arenaviruses. Red Book. 2009;2009(1):325–334. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cajimat MNB, et al. Genetic diversity among Bolivian arenaviruses. Virus Research. 2009;140(1–2):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enria DA, et al. Importance of dose of neutralising antibodies in treatment of Argentine haemorrhagic fever with immune plasma. Lancet. 1984;2(8397):255–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahanty S, et al. Low Levels of Interleukin-8 and Interferon-Inducible Protein–10 in Serum Are Associated with Fatal Infections in Acute Lassa Fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;183(12):1713–1721. doi: 10.1086/320722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maiztegui JI, Fernandez NJ, de Damilano AJ. Efficacy of immune plasma in treatment of Argentine haemorrhagic fever and association between treatment and a late neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1979;2(8154):1216–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eddy G, et al. Protection of monkeys against Machupo virus by the passive administration of Bolivian haemorrhagic feverimmunoglobulin (human origin) Bull World Health Organ. 1975:52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mcleod CG, et al. Pathology of chronic Bolivian hemorrhagic fever in the rhesus monkey. Am J Pathol. 1976;84(2):211–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCormick JB, et al. Lassa fever. Effective therapy with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(1):20–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601023140104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kilgore PE, et al. Treatment of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever with Intravenous Ribavirin. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997;24(4):718–722. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jahrling P, Trotter R, Barrero O. Crossprotection against Machupo virus with Candid 1 Junin virus vaccine. Proceedings of the second international conference on the impact of viral diseases on the development of Latin American countries and the Caribbean Region; 1988; Mar del Plata, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bradfute S, et al. A STAT-1 knockout mouse model for Machupo virus pathogenesis. Virology Journal. 2011;8(1):300. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Webb PA, et al. Some Characteristics of Machupo Virus, Causative Agent of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1967;16(4):531–538. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1967.16.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kastello MD, Eddy GA, Kuehne RW. A Rhesus Monkey Model for the Study of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1976;133(1):57–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eddy G, et al. Pathogenesis of Machupo virus infection in primates. Bull World Health Organ. 1975:52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McLeod CG, et al. Pathology of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever in the African Green Monkey. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1978;27(4):822–826. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *273.Patterson M, et al. Rescue of a Recombinant Machupo Virus from Cloned cDNAs and In Vivo Characterization in Interferon (αβ/γ) Receptor Double Knockout Mice. Journal of Virology. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02925-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Syromiatnikova S, et al. Chemotherapy for Bolivian hemorrhagic fever in experimentally infected guinea pigs. Vopr Virusol. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stephen EL, et al. Effect of interferon on togavirus and arenavirus infections of animals. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1977;35:449–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levis SC, et al. Endogenous Interferon in Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1984;149(3):428–433. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kenyon RH, et al. Treatment of Junin virus-infected guinea pigs with immune serum: development of late neurological disease. J Med Virol. 1986;20(3):207–18. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rugiero H, et al. Tratamiento de la Fiebre Hemorragica Argentina. Medicina. 1977;37:210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ambrosio A, et al. Argentine hemorrhagic fever vaccines. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(6):694–700. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.6.15198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters CJ. Emerging Infections: Lessons from the Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:189–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Enria DA, Maiztegui JI. Antiviral treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 1994;23(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]