Abstract

Background & Aims

Iron deficiency is often observed in obese individuals. The iron regulatory hormone hepcidin is regulated by iron and cytokines IL6 and IL1β. We examine the relationship between obesity, circulating levels of hepcidin and IL6 and IL1β, and other risk factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with iron deficiency.

Methods

We collected data on 675 adult subjects (>18 y old) enrolled in the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Subjects with transferrin saturation <20% were categorized as iron deficient, whereas those with transferrin saturation ≥20% were classified as iron normal. We assessed clinical, demographic, anthropometric, laboratory, dietary, and histologic data from patients, as well as serum levels of hepcidin and cytokines IL6 and IL1β. Univariate and multivariate analysis were used to identify risk factors for iron deficiency.

Results

One third of patients (231/675; 34%) were iron deficient. Obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome were more common in subjects with iron deficiency (P<.01), compared with those that were iron normal. Serum levels of hepcidin were significantly lower in subjects with iron deficiency (61±45 vs 81±51 ng/mL; P<.0001). Iron deficiency was significantly associated with female sex, obesity, increased body mass index and waist circumference, presence of diabetes, lower alcohol consumption, Black or American Indian/Alaska Native race (P≤.018), and increased levels of IL6 and IL1β (6.6 vs 4.8 for iron normal; P≤.0001 and 0.45 vs 0.32 for iron normal; P≤.005).

Conclusion

Iron deficiency is prevalent in patients with NAFLD and associated with female sex, increased body mass index, and non-white race. Serum levels of hepcidin were lower in iron-deficient subjects, reflecting an appropriate physiological response to decreased circulating levels of iron, rather than a primary cause of iron deficiency in the setting of obesity and NAFLD.

Keywords: NASH CRN, BMI, NAFLD, nutrition, ferroportin, inflammation

Introduction

Obesity and iron deficiency are considered the two most common nutritional disorders worldwide (1). The association between obesity and iron status was first described by Wenzel in 1962, who noted that obese adolescents had lower serum iron compared to non-obese adolescents (2). A diet rich in carbohydrates and fats and poor in nutrients such as iron, combined with a greater iron requirement in obese individuals may play a role (3). However, Menzie et al evaluated the role of dietary factors in obese ID individuals and did not find an association between iron intake and ID (4). More recently, research has focused on the role of systemic, obesity-related, low-grade inflammation leading to ID via increased hepcidin expression. (5–7).

In response to increased iron stores, hepcidin, the iron regulatory hormone, binds and internalizes the cellular iron export protein ferroportin, thus downregulating iron efflux from the enterocyte, macrophage and hepatocyte (8). Conversely, decreased/deficient iron stores down regulate hepcidin in order to restore iron balance to appropriate physiologic levels. Hepcidin expression is also increased in chronic inflammation, by inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) via STAT3 (9). Hepcidin is predominantly expressed in the liver, but also in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue, albeit at such a low level it may not contribute to systemic hepcidin levels (6, 10). Thus, the impact of obesity-induced hepcidin upregulation and the relationship between liver vs adipose-derived hepcidin, and iron regulation in the setting of obesity is not well understood.

NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the US with an estimated prevalence of 30% among US adults and is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome (11). Up to a third of all patients with NAFLD progress to the more severe form called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), characterized by hepatocellular ballooning, inflammation and variable fibrosis (12). We have previously shown, using a cutoff of serum ferritin (SF) 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, that there is an inverse relationship between BMI and serum iron studies in patients with NAFLD (i.e., subjects with low TS and low SF had significantly higher BMI) (13). We have also previously shown that subjects with hepatic iron staining had higher levels of serum hepcidin (14). The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between circulating hepcidin level, obesity-induced systemic inflammation, and iron deficiency and to identify the prevalence of and associated risk factors for iron deficiency in patients with NAFLD.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Six hundred and seventy five adult (age>18 yrs) subjects enrolled in NASH CRN studies between October 2004 and February 2008, with biopsy proven NAFLD (defined as >5% steatosis) and serum iron studies within 6 months of the liver biopsy were studied. The NASH CRN Database and PIVENS Trial inclusion/exclusion criteria have been reported elsewhere (15, 16). Demographic information including age, sex, ethnicity and race and a detailed medical history including co-morbidities such as history of DM, hypertension and hyperlipidemia and menstrual history in women were obtained from patient interviews during screening. Dietary consumption of iron, vitamin C, tea and coffee and supplemental vitamin C were determined from the Block 98 food frequency questionnaire (NutritionQuest, Berkeley, CA); alcohol consumption was determined from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaires (17). A complete physical examination including measurement of weight, height, waist and hip circumference was obtained. Subjects with a BMI of ≥ 30 were defined as obese. ID was defined as transferrin saturation (TS; serum iron/total iron binding capacity) below 20%, indicative of iron deficiency (18, 19). We also investigated the presence of iron deficiency anemia in our cohort using the criteria of serum ferritin<30, TS<20 and hemoglobin<12 in females and <13 in males; only 15 subjects met this criteria and therefore we did not analyze this subset separately. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (MS) in this cohort was defined using the World Health Organization criteria. All subjects gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review board at each local site of the NASH CRN.

Serologic data

Clinical laboratory data including hematologic, hepatic and metabolic, lipid and serum iron assessments were analyzed for subjects with values collected within 6 months of the liver biopsy. Serum hepcidin levels, available in 558 subjects, were determined by ELISA (Intrinsic LifeSciences, San Diego, CA) (20). The lower limit of detection in this assay is 5 ng/ml. Eight subject values were below this limit and a value of 5ng was imputed for the analysis. Plasma IL6 and IL1β levels, available in 371 and 242 subjects, respectively, were determined using Luminex technology and the human cytokine LINCOplex kit (Catalog number HCYTO-60K, Millipore, St. Charles, MO). The lower limit of detection for the assays were 0.79 and 0.19 pg/mL, respectively. Two subject IL6 values were below this limit and a value of 0.79 pg/mL was imputed for the analysis. Fifty two IL1β values were below this limit including 13 ID subjects. A value of 0.19 pg/mL was imputed for the analysis.

HFE genotyping

We examined the relationship between ID and the presence of mutations in the hemochromatosis gene HFE, which influence hepcidin production. Genotyping for the two common HFE mutations C282Y (rs1800562) and H63D (rs1799945) was performed using a real time genotyping assay as previously described (14). HFE genotyping data was available in 500 subjects.

Liver histology

All patients underwent a liver biopsy which was stained for hematoxylin-eosin, Masson’s trichrome and Perls’ iron stain. Histologic features of NAFLD and iron accumulation were assessed by the pathology committee of the NASH CRN in a centralized consensus review format, as previously described (21). NAFLD activity score (NAS, range 1–8) was tabulated by summing scores for steatosis, lobular inflammation, and ballooning degeneration.

Statistical analysis

Data were compared using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Univariate logistic and stepwise forward multivariate logistic regression (p value of <0.20 was used as a cutoff for incorporation into the model) were used to identify independent predictors for iron deficiency. Models were also created to identify risk factors in each sex. Differences in histological features such as fibrosis stage, steatosis and lobular inflammation grade were analyzed using ordinal regression. All analyses were performed using STATA (version 12, College Station, TX, USA). Nominal, two-sided p-values were used and were considered to be statistically significant if p<0.05. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

Results

Patient characteristics

Six hundred seventy five subjects (mean age of 48 ± 12 years) with biopsy-proven NAFLD (defined as >5% steatosis) and serum iron assessments within six months of their liver biopsy were evaluated in the present study. 34% (231 subjects) were ID and 66% (444 subjects) were iron normal (TS≥20%). Overall the majority of subjects in this study cohort were white (84%), obese (70%) and female (63%). Patient characteristics including clinical, demographic, racial, and specific dietary/behavioral factors thought to effect iron absorption, such as dietary iron, vitamin C, caffeine and alcohol consumption are summarized in Table 1. Subjects with ID were significantly more likely to be female, obese, and with greater waist circumference and BMI compared to iron normal subjects. ID subjects were also more likely to have DM and MS. When we analyzed the presence of iron deficiency according to race, we found that the prevalence of ID was significantly increased among those with either Black or AI/AN race. Lower alcohol consumption was the only dietary factor that was associated with ID. There were no differences in the presence of the C282Y or H63D HFE hemochromatosis gene mutations between ID and iron normal groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Iron Deficient | Iron Normal | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 231 (34) | 444 (66) | |

| Age (yrs) | 47.6 ± 11.7 | 48.0 ± 12.2 | 0.96 |

| Female (No.) | 181 (78) | 243 (55) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.7 ± 6.9 | 33.1 ± 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Obese (≥30 BMI) | 182 (79) | 291 (66) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference | 111 ± 15 | 107 ± 13 | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 82 (36) | 97 (22) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 167 (74) | 283 (64) | 0.01 |

| Race (No.) | |||

| White | 193 (84) | 377 (85) | 0.65 |

| Black | 15 (6.5) | 5 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 7 (3.0) | 26 (5.9) | 0.13 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 22 (9.5) | 21 (4.7) | 0.02 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 8 (1.8) | 0.06 |

| Other | 21 (9.1) | 37 (8.3) | 0.63 |

| Ethnicity (No.) | 0.63 | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 203 (88) | 384 (86) | |

| Hispanic | 28 (12) | 60 (14) | |

| No. of alcoholic drinks/week | 0.36 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.007 |

| No. of coffee/tea drinks/day | 7.8 ± 9.7 | 7.0 ± 8.8 | 0.45 |

| Dietary iron consumed (mg/day) | 14.0 ± 9.1 | 14.1 ± 8.0 | 0.61 |

| Dietary vitamin C (mg/day) | 109 ± 87 | 103 ± 76 | 0.45 |

| Supplemental vitamin C (mg/day) | 163 ± 351 | 157 ± 355 | 0.79 |

| Presence of C282Y HFE mutations | 19 (15) | 40 (17) | 0.77 |

| Presence of H63D HFE mutations | 41 (27) | 93 (32) | 0.33 |

Values are N (%) or mean ± SD

P values from Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

The proportion of subjects that were ID compared to iron normal, analyzed according to sex and obesity status is shown in Figure 1. Women were much more likely to be ID compared to men (43% vs 20%, p<0.001). Additionally, a greater proportion of women with ID were obese compared to men (35% vs 14%, p<0.001). A higher percentage of women with regular periods were ID compared to postmenopausal women, although this difference was not statistically significant (51% vs. 40%, respectively, p=0.15). Obesity was more prevalent among ID women with regular periods compared to ID women without periods (46% vs 29%, p=0.042).

Figure 1.

Proportion of subjects with iron deficiency and obesity according to A) male sex; B) female sex; C) females with regular periods; D) females with no periods. The percentage of the total is labeled for each pattern. * p<0.001 compared to males; † p<0.05 compared to subjects with regular periods (Fishers exact test). Standard deviations are indicated by the error bars.

Differences in laboratory tests between iron deficient and iron normal subjects

Significant differences in routine clinical laboratory assessments, serum iron studies and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL6 and IL1β between the two groups of patients are shown in Table 2. ID subjects had lower ALT, and total and direct bilirubin levels, but higher ceruloplasmin and HbA1c levels, AST/ALT ratios, and platelet counts. ID subjects had significantly lower hemoglobin, serum iron, ferritin and TS and higher total iron binding capacity, consistent with an iron depleted state. Plasma levels of IL6 and IL1β were significantly increased in ID subjects compared to iron normal subjects (p≤0.0001; p≤0.008, Table 2), suggesting systemic inflammation may be greater in ID compared to iron normal subjects.

Table 2.

Laboratory value differences among iron deficient and normal patients

| Variable* | Iron Deficient | Iron Normal | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 58 (36–80) | 67 (44–101) | 0.0004 |

| AST/ALT | 0.81 (0.66–1.0) | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) | <0.0001 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.8 (5.4–6.4) | 5.6 (5.3–6.2) | 0.002 |

| Platelets (K/cmm) | 259 (204–308) | 235 (195–274) | 0.0001 |

| Ceruloplasmin (mg/dL) | 31 (27–38) | 28 (23–35) | 0.008 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.9 (13.0–14.7) | 14.6 (13.7–15.6) | <0.0001 |

| Serum iron (μg/dL) | 59 (50–70) | 103 (86–123) | <0.0001 |

| Total iron binding capacity (μg/dL) | 399 (363–437) | 347 (309–389) | <0.0001 |

| Transferrin saturation (iron/TIBC) | 0.16 (0.12–0.18) | 0.28 (0.24–0.36) | <0.0001 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL) | 92 (47–155) | 219 (103–361) | <0.0001 |

| Interleukin 6 | 6.6 (4.4–10.3) | 4.8 (3.1–7.9) | 0.0001 |

| Interleukin 1β | 0.45 (0.25–0.83) | 0.32 (0.19–0.59) | 0.009 |

Values are medians (IQR)

P values from Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Relationship of circulating hepcidin levels and factors associated with ID

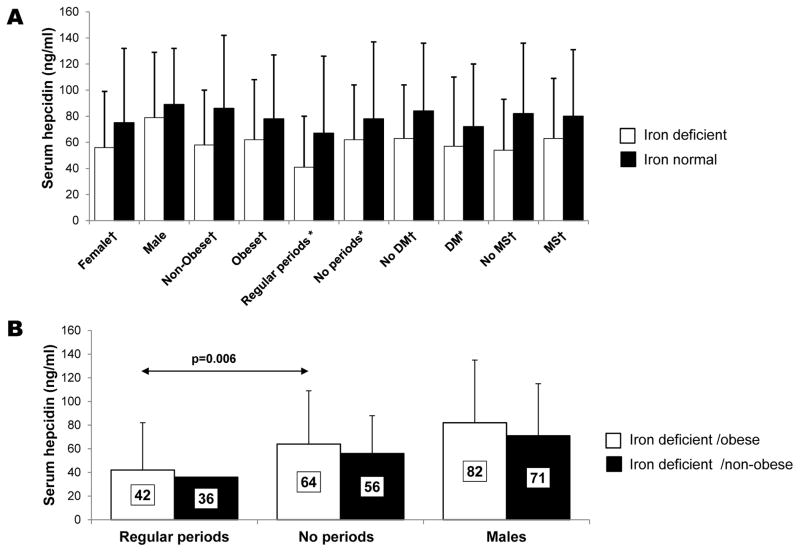

Figure 2A shows the relative mean serum hepcidin level in ID subjects compared to iron normal subjects stratified according to sex, menstrual status, or the presence of obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Serum hepcidin levels were lower in ID subjects compared to iron normal subjects (p<0.05), except in males. Women who reported having regular periods showed the largest difference in serum hepcidin (−39%; 41 vs 67 ng/ml, p=0.03) between ID and iron normal subjects, respectively, and the lowest mean levels among all groups, reflecting the effect of blood loss on circulating hepcidin levels.

Figure 2.

A) Comparison of the mean serum hepcidin values of ID vs iron normal NAFLD subjects according to sex, menstrual status, presence of obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome. †p<0.001; * p<0.05 (Wilcoxon rank sum test). B) Comparison of the mean serum hepcidin values of ID NAFLD subjects according to sex, presence of obesity, and menarche. Standard deviations are indicated by the error bars.

We compared serum hepcidin levels in obese vs non obese ID patients, stratified according to sex and menstrual status (Figure 2B). In each group, non-obese ID subjects had 13–14% lower serum hepcidin levels compared to obese ID subjects. We also observed that obese ID women with regular periods had significantly lower serum hepcidin levels compared to obese ID women with no periods (42 vs 64 ng/ml, respectively, p=0.006), suggesting iron loss effectively reduces serum hepcidin even in the setting of obesity.

Histologic differences between groups

No significant difference in mean grade of steatosis (range 0–3; 1.7±0.9 vs 1.8±0.9), lobular inflammation (range 0–3; 1.6±0.7 vs 1.6±0.7), portal inflammation (range 0–2; 1.1±0.6 vs 1.0±0.6), ballooning (range 0–2; 1.1±0.9 vs 1.1±0.9) fibrosis (range 0–4; 1.5±1.3 vs 1.6±1.3) or NAS index (range 0–8; 4.4±1.7 vs 4.5±1.6) was noted between the ID and iron normal subjects, respectively.

Factors associated with the presence of iron deficiency

Logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate potential risk factors for ID in this population (see Table 3). ID was associated with female sex, obesity, increased BMI and waist circumference, presence of DM or MS, fewer alcoholic drinks consumed per week and Black and AI/AN race in univariate analysis. To investigate the relationship between the combined effects of these factors on ID, stepwise multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed with ID as the dependent variable and each of the variables significantly associated with ID on univariate analysis as independent variables; a p value of <0.20 was used as a cutoff for incorporation into the model. Overall, female sex, increased BMI, Black and AI/AN race and decreased ALT and serum hepcidin were independently associated with ID. In addition, multivariate regression analysis was performed in men and women as two separate groups. BMI, ALT, serum hepcidin and AI/AN race were independently associated with ID in women, while in men only waist circumference was independently associated with ID. Potential factors which could explain the ID phenotype in the Black and AI/AN race are shown in Table 4. The only significant difference between Black subjects was that none of the ID Black subjects took supplemental vitamin C, which increases intestinal iron absorption (p=0.02). AI/AN ID subjects had increased BMI and waist circumference and were more likely to be obese compared to the AI/AN iron normal subjects (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Independent predictors of iron deficiency on univariate* and multivariate† logistic regression modeling

| OR | 95% Conf. Int. | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Female sex | 2.99 | 2.08–4.31 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1.99 | 1.37–2.90 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes present | 1.97 | 1.39–2.80 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.07 | 1.04–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Hepcidin (ng/ml) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | <0.001 |

| Black race | 6.10 | 2.19–17.00 | 0.001 |

| Waist circumference | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.79 | 0.66–0.93 | 0.005 |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 1.59 | 1.11–2.27 | 0.011 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2.12 | 1.14–3.94 | 0.018 |

| Model 1 (all subjects) | |||

| Female sex | 2.23 | 1.43–3.48 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.07 | 1.03–1.10 | <0.001 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.44 | 1.60–7.41 | 0.002 |

| Hepcidin (ng/ml) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.003 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.005 |

| Black race | 3.54 | 1.12–10.81 | 0.027 |

| Model 2 (female subjects) | |||

| BMI mean (kg/m2) | 1.06 | 1.02–1.10 | 0.002 |

| Hepcidin (ng/ml) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.006 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.009 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.45 | 1.26–9.42 | 0.016 |

| Model 3 (male subjects) | |||

| Waist circumference | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.005 |

Univariate logistic was performed using presence of ID as the dependent variable.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed with ID as the dependent variable and each of the variables significantly associated with ID in univariate analysis; a p value of <0.20 was used as a cutoff for incorporation into the model.

Table 4.

Potential factors associated with iron deficiency in Black or American Indian/Alaska Native Race

| Iron Deficient | Iron Normal | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Race | |||

| Number | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | |

| Female sex | 13 (87) | 5 (100) | 1.0 |

| Obesity | 15 (100) | 4 (80) | 0.25 |

| Diabetes present | 8 (53) | 3 (60) | 1.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 38.8 ± 6.4 | 34.4 ± 5.8 | 0.089 |

| Waist circumference | 114 ± 17 | 107 ± 14 | 0.52 |

| No. of alcoholic drinks/week | 0.1 ± 0.17 | 0 ± 0 | 0.21 |

| Dietary iron consumed (mg/day) | 11.3 ± 8.5 | 14.1 ± 8.3 | 0.38 |

| Dietary vitamin C (mg/day) | 134 ± 157 | 108 ± 58 | 0.51 |

| Supplemental vitamin C (mg/day) | 0 ± 0 | 140 ± 269 | 0.02 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native Race | |||

| Number | 22 (51) | 21 (49) | |

| Female sex | 16 (73) | 12 (57) | 0.35 |

| Obesity | 19 (86) | 12 (57) | 0.045 |

| Diabetes present | 8 (36) | 4 (19) | 0.31 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 36.6 ± 4.3 | 32.3 ± 6.0 | 0.009 |

| Waist circumference | 113 ± 13 | 103 ± 12 | 0.016 |

| No. of alcoholic drinks/week | 0.14 ± 0.18 | 0.63 ± 1.9 | 0.98 |

| Dietary iron consumed (mg/day) | 13.0 ± 6.2 | 15.4 ± 6.3 | 0.24 |

| Dietary vitamin C (mg/day) | 130 ± 153 | 117 ± 60 | 0.65 |

| Supplemental vitamin C (mg/day) | 118 ± 263 | 65 ± 154 | 0.38 |

Values are N (%) or mean ± SD

P values from Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

Discussion

Iron deficiency is common in obese children and adults; the cause of this association is not entirely clear and has been linked to a number of factors (2–7). In the present study we found that one third of adult NAFLD subjects were iron deficient as defined by TS<20%, and that female sex, obesity (BMI ≥30), type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome were more common in this cohort. We also found that alcohol consumption is protective against ID, consistent with our previous data from a population-based study (22). Alcohol has been shown to decrease hepcidin expression, which could lead to increased iron absorption and recycling (23). Both in vitro and human studies have described that alcohol suppressed hepcidin transcription in the liver and may protect from iron deficiency (24). However, alcohol intake was unlikely to be a major factor on hepcidin levels in this study, given that excessive alcohol consumption was an exclusion criterion for all NASH CRN studies (15, 16). There were no differences in the presence of C282Y or H63D HFE hemochromatosis gene mutations between ID and iron normal groups, which is in agreement with our previous report in a related cohort showing that heterozygous C282Y or H63D subjects did not have statistically different levels of serum iron parameters compared to wild type subjects (14). No other dietary factor was associated with ID, including amount of dietary iron or supplemental and dietary vitamin C or caffeine consumption. In addition, we found that ID was associated with Black or AI/AN race. When each sex was considered separately, in women only BMI and AI/AN race, and only waist circumference in men, were independent predictors of ID on multivariate logistic regression. Obesity was more prevalent among the ID women with regular menses compared to ID women with amenorrhea; this was an interesting observation with no ready explanation and we speculate that amenorrhea maybe secondary to polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may be contributing as PCOS is associated with increased insulin resistance.

We found that overall, serum hepcidin was lower in ID subjects compared to iron normal subjects, despite increased cytokine levels suggesting the presence of chronic inflammation which would have been expected to increase serum hepcidin. These findings are in agreement with our previous report that subjects with hepatic iron staining had higher levels of serum hepcidin than subjects without stainable hepatic iron (14). Although it is possible that obesity-induced inflammation-mediated hepcidin up regulation would contribute to the onset of ID among obese people, the decreased circulating hepcidin we observed in our ID subjects in comparison to the iron normal subjects reflects an appropriate physiologic response to current body iron stores; when the body iron stores are low, hepcidin production is decreased resulting in increased intestinal iron absorption and macrophage iron release. These data suggest that body iron stores rather than chronic inflammation are the primary signal mediating hepcidin levels in our ID NAFLD subjects.

Our data are in agreement with several animal studies suggesting that both iron deficiency, induced by either phlebotomy treatment (25, 26), or dietary insufficiency (26, 27), cause down regulation of hepcidin even in the presence of experimentally induced inflammation. In an elegant study by Theurl et al, these authors investigated hepcidin signaling in rat models of anemia of chronic disease (high hepcidin) and anemia of chronic disease with true iron deficiency (anemia of chronic disease/ID; low hepcidin levels) induced by either phlebotomy treatment or dietary iron insufficiency (26). Despite similarly high levels of STAT3, the inflammatory pathway hepcidin transactivator, in both models, the anemia of chronic disease/ID rats had decreased hepcidin transcription. This effect was mediated by inhibition of bone morphogenic protein-6 expression and reduced phosphorylation and trafficking of SMAD1/5/8. Taken together, these and other data and our results indicate that hepcidin regulation in the presence of multiple divergent signals in vivo maybe determined by the most urgent physiologic needs/strength of the signal within the organism rather than a set hierarchy of hepcidin regulatory signals (7, 26, 28).

Body iron stores and increased serum ferritin levels have been associated with more severe NAFLD (13, 21). In this study we did not observe any significant difference in histologic features of NASH between ID and iron normal NAFLD patients. However, subjects with ID had significantly lower ALT levels even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, DM and NAS (data not shown).

An interesting observation in the current study was that ID was more prevalent among subjects self-described as Black or AI/AN race. When we further investigated the presence of additional risk factors for ID in these subjects we found that AI/AN ID subjects had increased BMI and waist circumference and were more likely to be obese compared to the AI/AN iron normal subjects. We also found that none of the Black ID subjects took supplemental vitamin C, compared to mean consumption of 140 ± 269 mg/day in Black iron normal subjects. However, we interpret these findings with caution given the small number of subjects with these racial backgrounds.

Both obesity and NAFLD are inflammatory conditions and we cannot distinguish the source of inflammation and whether there was an independent effect of obesity on hepcidin level, since all patients in the NASH CRN Database, by definition had NAFLD. Studies have shown that NAFLD patients have significantly more colorectal (CR) neoplasia and early CR cancer compared to those without NAFLD (29). We did not have data available on screening for colorectal neoplasia; thus, the potential of underlying gastrointestinal bleed from undetected CR neoplasia may potentially be a cause for ID.

In conclusion, our study shows that iron deficiency is common in NAFLD patients. Circulating serum hepcidin levels in NAFLD patients with iron deficiency are low reflecting an appropriate physiologic response of hepcidin signaling to iron deficiency. Obesity and female sex are likely the most important risk factors of ID in NAFLD subjects; however alcohol consumption, presence of diabetes and potentially racial background may also be contributing factors. We conclude that increased hepcidin as a result of obesity-induced systemic inflammation may initially contribute to iron deficiency but once ID is established hepcidin is appropriately down regulated.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Several clinical centers use support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) in conduct of NASH CRN Studies (grants UL1TR000439, UL1TR000077, UL1TR000436, UL1TR000150, UL1TR000424, UL1TR000006, UL1TR000448, UL1TR000040, UL1TR000100, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000423, UL1TR000058, UL1TR000067, UL1TR000454).

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the BRI Genotyping Core facility. We would also like to thank Laura Wilson and Patricia Belt for assistance in preparation of the data. We thank Dr. Mark Westerman at Intrinsic Life Sciences for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- ID

iron deficient

- IN

iron normal

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NAS

NAFLD activity score

- TS

transferrin saturation

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- MS

metabolic syndrome

- AI/AN

American Indian/Alaska Native race

- JAK/STAT

Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription

Members of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Stephanie H. Abrams, MD, MS; Ryan Himes, MD; Rajesh Krisnamurthy, MD; Leanel Maldonado, RN (2007–2012); Beverly Morris Case Western Reserve University Clinical Centers:

MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH: Patricia Brandt; Srinivasan Dasarathy, MD; Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD; Carol Hawkins, RN; Arthur J. McCullough, MD

Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH: Srinivasan Dasarathy, MD; Arthur J. McCullough, MD; Mangesh Pagadala, MD; Rish Pai, MD; Ruth Sargent, LPN; Shetal Shah, MD; Claudia Zein, MD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH: Kimberlee Bernstein, BS, CCRP ; Kim Cecil, PhD; Stephanie DeVore, MSPH (2009–2011); Rohit Kohli, MD; Kathleen Lake, MSW (2009–2012); Daniel Podberesky, MD; Crystal Slaughter, BA, CCRP; Stavra Xanthakos, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: Gerald Behr, MD; Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD; Ali Mencin, MD; Nadia Ovchinsky, MD; Elena Reynoso, MD

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Manal F. Abdelmalek, MD; Mustafa Bashir, MD; Stephanie Buie; Anna Mae Diehl, MD; Cynthia Guy, MD; Christopher Kigongo; Yi-Ping Pan; Dawn Piercy, FNP (2004–2012); Melissa Wagner

Emory University, Atlanta, GA: Adina Alazraki, MD; Rebecca Cleeton, MPH; Saul Karpen, MD, PhD; Nicholas Raviele; Miriam Vos, MD, MSPH

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN: Elizabeth Byam, RN; Naga Chalasani, MD; Oscar W. Cummings, MD; Cynthia Fleming, RN, MSN; Marwan Ghabril, MD; Ann Klipsch, RN; Smitha Marri, MD; Jean P. Molleston, MD; Linda Ragozzino, RN; Kumar Sandrasegaran, MD; Girish Subbarao, MD; Raj Vuppalanchi, MD

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD: Kimberly Pfeifer, RN; Ann Scheimann, MD; Michael Torbenson, MD

Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital, New York, NY: Ronen Arnon, MD; Mariel Boyd, CCRP

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine/Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Katie Amsden, Mark H. Fishbein, MD; Elizabeth Kirwan, RN; Saeed Mohammad, MD; Ann Quinn, RD (2010–2012); Cynthia Rigsby, MD; Peter F. Whitington, MD

Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO: Sarah Barlow, MD (2002–2007); Jose Derdoy, MD (2007–2012); Ajay Jain MD; Debra King, RN; Pat Osmack; Joan Siegner, RN; Susan Stewart, RN; Brent A. Neuschwander-Tetri, MD; Dana Romo

University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Brandon Ang; Sandra Arroyo; Cynthia Behling, MD, PhD; Archana Bhatt; Jennifer Collins; Iliana Doycheva, MD; Janis Durelle; Tarek Hassanein, MD (2004–2009); Joel E. Lavine, MD PhD (2002–2010); Rohit Loomba, MD, MHSc; Michael Middleton, MD, PhD; Kimberly Newton, MD; Phirum Nguyen; Mazen Noureddin, MD; Melissa Paiz; Heather Patton, MD; Jeffrey B. Schwimmer, MD; Claude Sirlin, MD; Patricia Ugalde-Nicalo

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Bradley Aouizerat, PhD; Nathan M. Bass, MD, PhD (2002–2011); Danielle Brandman, MD; Linda D. Ferrell, MD; Shannon Fleck; Ryan Gill, MD, PhD; Bilal Hameed, MD; Alexander Ko; Camille Langlois; Emily Rothbaum Perito, MD; Aliya Qayyum, MD; Philip Rosenthal, MD; Norah Terrault, MD, MPH; Patrika Tsai, MD

University of California San Francisco-Fresno, Fresno, CA: Pradeep Atla, MD; Cathy Hurtado; Rebekah Garcia; Sonia Garcia; Muhammad Sheikh, MD; Mandeep Singh, MD

University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA: Kara Cooper; Simon Horslen, MB ChB; Evelyn Hsu, MD; Karen Murray, MD; Randolph Otto, MD; Deana Rich; Matthew Yeh, MD, PhD; Melissa Young

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: Sherry Boyett, RN, BSN; Laura Carucci, MD; Melissa J. Contos, MD; Michael Fuchs, MD; Amy Jones; Kenneth Kraft, PhD; Velimir AC Luketic, MD; Kimberly Noble; Puneet Puri, MD; Bimalijit Sandhu, MD (2007–2009); Arun J. Sanyal, MD; Carol Sargeant, RN, BSN, MPH (2004–2012); Jolene Schlosser; Mohhamad S. Siddiqui, MD; Ben Wolford; Melanie White, RN, BSN (2006–2009)

Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA: Sarah Ackermann; Shannon Cooney; David Coy, MD, PhD; Katie Gelinas; Kris V. Kowdley, MD; Maximillian Lee, MD, MPH; Tracey Pierce; Jody Mooney, MS; James E. Nelson, PhD; Lacey Siekas; Cheryl Shaw, MPH; Asma Siddique, MD; Chia Wang, MD

Washington University, St. Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD; Kathryn Fowler, MD

Resource Centers

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD: Gilman D. Grave, MD

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD: Edward C. Doo, MD; Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD; Patricia R. Robuck, PhD, MPH (2002–2011); Averell Sherker, MD

Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health (Data Coordinating Center), Baltimore, MD: Patricia Belt, BS; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; Erin Corless, MHS; Michele Donithan, MHS; Milana Isaacson, BS; Kevin P. May, MS; Laura Miriel, BS; Alice Sternberg, ScM; James Tonascia, PhD; Aynur Ünalp-Arida, MD, PhD; Mark Van Natta, MHS; Ivana Vaughn, MPH; Laura Wilson, ScM; Katherine Yates, ScM

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

AS, JEN and KVK were involved in all aspects of the study including: concept, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and approval of the final of the manuscript. BA and MMY were involved in collection of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and approval of the final of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Harris RJ. Nutrition in the 21st century: what is going wrong? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:154–158. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenzel BJ, Stults HB, Mayer J. Hypoferraemia in obese adolescents. Lancet. 1962;2:327–328. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(62)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Micozzi MS, Albanes D, Stevens RG. Relation of body size and composition to clinical biochemical and hematologic indices in US men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1276–1281. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.6.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzie CM, Yanoff LB, Denkinger BI, et al. Obesity-related hypoferremia is not explained by differences in reported intake of heme and nonheme iron or intake of dietary factors that can affect iron absorption. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanoff LB, Menzie CM, Denkinger B, et al. Inflammation and iron deficiency in the hypoferremia of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1412–1419. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekri S, Gual P, Anty R, et al. Increased adipose tissue expression of hepcidin in severe obesity is independent from diabetes and NASH. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:788–796. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tussing-Humphreys LM, Nemeth E, Fantuzzi G, et al. Elevated Systemic Hepcidin and Iron Depletion in Obese Premenopausal Females. Obesity. 2010;18:1449–1456. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306:2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee P, Peng H, Gelbart T, et al. Regulation of hepcidin transcription by interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1906–1910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409808102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tussing-Humphreys L, Frayn KN, Smith SR, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue from obese and lean adults does not release hepcidin in vivo. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:2197–2206. doi: 10.1100/2011/634861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332:1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowdley KV, Belt P, Wilson LA, et al. Serum ferritin is an independent predictor of histologic severity and advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:77–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.24706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson JE, Brunt EM, Kowdley KV, et al. Lower serum hepcidin and greater parenchymal iron in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients with C282Y HFE mutations. Hepatology. 2012;56:1730–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.25856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:913–924. doi: 10.1002/hep.23784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1675–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, et al. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrier SL. Causes and diagnosis of anemia due to iron deficiency. In: Basow DS, editor. UpToDate. UpToDate; Waltham, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung M, Moorthy D, Hadar N, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 83. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: Oct, 2012. Biomarkers for Assessing and Managing Iron Deficiency Anemia in Late-Stage Chronic Kidney Disease. Publication No. 12(13)-EHC140-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganz T, Olbina G, Girelli D, et al. Immunoassay for human serum hepcidin. Blood. 2008;112:4292–4297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson JE, Wilson L, Brunt EM, et al. Relationship between the pattern of hepatic iron deposition and histological severity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:448–457. doi: 10.1002/hep.24038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ioannou GN, Weiss NS, Kowdley KV. Relationship between transferrin-iron saturation, alcohol consumption and the incidence of cirrhosis and liver cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison-Findik DD, Schafer D, Klein E, et al. Alcohol metabolism-mediated oxidative stress down-regulates hepcidin transcription and leads to increased duodenal iron transporter expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22974–22982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa-Matos L, Batista P, Monteiro N, et al. Liver hepcidin mRNA expression is inappropriately low in alcoholic patients compared with healthy controls. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1158–65. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328355cfd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lasocki S, Millot S, Andrieu V, et al. Phlebotomies or erythropoietin injections allow mobilization of iron stores in a mouse model mimicking intensive care anemia. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2388–94. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818103b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theurl I, Schroll A, Nairz M, et al. Pathways for the regulation of hepcidin expression in anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency anemia in vivo. Haematologica. 2011;96:1761–1769. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.048926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darshan D, Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, et al. Severe iron deficiency blunts the response of the iron regulatory gene Hamp and pro-inflammatory cytokines to lipopolysaccharide. Haematologica. 2010;95:1660–1667. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.022426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darshan D, Anderson GJ. Interacting signals in the control of hepcidin expression. Biometals. 2009;22:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9187-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadlmayr A, Aigner E, Steger B, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an independent risk factor for colorectal neoplasia. J Intern Med. 2011;270:41–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]