Abstract

The expression of monocyte surface markers was compared between tuberculosis patients with and without type 2 diabetes (DM2). DM2 was associated with increased CCR2 expression, which may restrain monocyte traffic to the lung. Other host factors associated with baseline monocyte changes were older age (associated with lower CD11b) and obesity (associated with higher RAGE). Given that DM2 patients are more likely to be older and obese, their monocytes are predicted to be altered in function in ways that affect their interaction with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Diabetes, Monocyte, Innate immunity, CCR2, CD11b, RAGE

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) increases the risk for tuberculosis (TB), and those who have developed TB (TB-DM) may take longer to clear Mycobacterium tuberculosis and have a higher risk of death.1-4 The increased susceptibility of DM2 patients to TB is likely explained by their dysfunctional immunity.5-9 An approach to identify defects in the immune response of DM2 patients to M. tuberculosis has been to identify differences between TB-DM and TB patients without DM2 (TB-no DM). Such studies have shown variable results, but the most recent where control for host factors were taken into account indicate that white blood cells (and T lymphocytes) from TB-DM patients secrete more Th1 and Th17 cytokines, and have an elevated frequency of single- and double-cytokine producing CD4+ Th1 cells in response to M. tuberculosis antigens.6-8 These findings suggest that TB-DM patients have a hyper-reactive immune response to M. tuberculosis, but it is unclear whether this is a cause and/or consequence of the higher susceptibility of DM2 patients to TB, and if this immunity is effective for M. tuberculosis elimination.

Blood monocytes play a key role in TB given their prompt migration to the lung upon initial M. tuberculosis infection, where they differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells for antigen presentation and secretion of cytokines. Furthermore, M. tuberculosis can enter and replicate (or be contained) within monocytes.10 Therefore, monocyte alterations in TB-DM patients may influence the clinical outcome. Blood monocytes are heterogeneous and can be divided into subsets:11-13 The “classical” subtype (CD14++CD16-) comprises about 80% and these cells are highly phagocytic. The “non-classical” subtype (CD14+CD16+) comprises about 12% and these cells appear to be the most mature and have higher MHC-II expression, and the “intermediate” subtype (CD14++CD16+) comprise about 5% of the total and these cells express a combination of characteristics of the two other subsets. There appears to be a developmental relationship between these subsets (classical to intermediate to non-classical) as well as changes in their distribution associated with clinical diseases, including TB.14-17 The characteristics of baseline blood monocytes from TB patients with and without DM2 has never been evaluated.18

We recently found that DM2 patients who are M. tuberculosis-naïve have monocytes with reduced phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis when compared to controls.19 For the present study we speculated that once DM2 patients develop TB, their monocytes may further influence the response to the bacterium in ways that differ from non-DM2 hosts. To begin exploring this, the goal of the present study was to determine whether there are differences in the phenotype of blood monocytes from TB-DM versus TB-no DM that would help to explain the role of these circulating phagocytes in the higher susceptibility and worse prognosis of DM2 patients with TB.

2. Methods

2.1 Participant enrollment and characterization

The enrollment and characterization of TB suspects in TB clinics from south Texas and northeastern Mexico have been described previously.20 For this study we identified 32 culture-positive TB patients who were HIV-negative and had received anti-TB treatment for no more than 3 days. Sixteen (50%) had DM2 with chronic hyperglycemia (HbA1c > 6.5%). The TB-DM patients tended to be older than TB-no DM controls (p=0.07), but the remaining sociodemographics, body-mass index (BMI) and TB characteristics [68% BCG vaccination, 91% smear positive, median (interquartile range) days of treatment prior to enrollment 1(1.7)] were similar. This study was approved by the committees for the protection of human subjects of the participating institutions and all participants signed the informed consent.

2.2 Monocyte isolation and flow cytometry

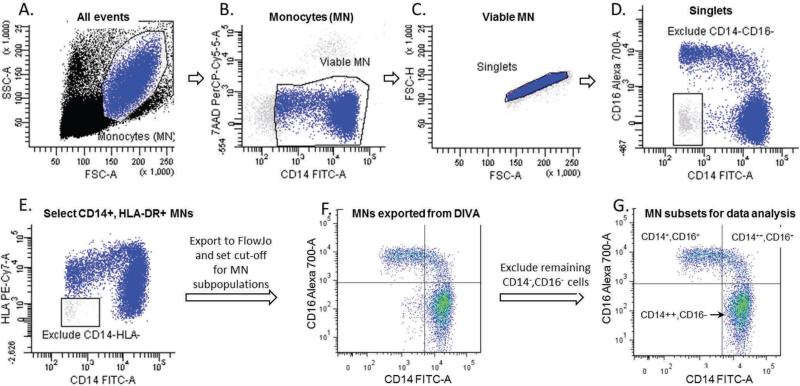

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated over a ficoll cushion and stored frozen.19 Cells were thawed, blocked for Fc receptors and stained with surface markers for CD14-FITC (Southern Biotechnology Associates), CD16-AF700, CCR2-AF647 (BD Biosciences), HLA-DR-PE-Cy7, CD11b-APC-Cy7, TLR-2-APC, TLR4-PE.Cy7, HLA-DR-eFluor780 (eBioscience) and RAGE (AbCAM) detected with a goat anti-rabbit-PE. Acquisition was conducted in a FACS CANTO-II using FACS DIVA 6.0 (BD Biosciences). Viable monocytes (7-AAD-negative) were identified based on scatter properties and CD14 staining, and their distribution into sub-populations and median fluorescence intensity of each marker was determined using FlowJo (TreeStar, Version 7.6.5); Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Monocyte gating. During acquisition with FACS DIVA monocytes were identified based on their scatter properties (A). We then excluded dead (7AAD-positive) and most of the CD14-negative cells (B), doublets (C), cells that were CD14 negative/CD16-negative (D) and CD14-negative/HLA-negative (E). The FCS files with these monocyte populations were then exported to FlowJo (F), where a cut-off value for CD14 and CD16 was established based on histograms of all of the study participants to define the final cut-off for CD14++CD16- (classical), CD14++CD16+, (intermediate) and CD14+CD16+ (non-classical) subpopulations for analysis (G). The remaining CD14-CD16- cells were excluded from final analysis.

3. Results

We found no differences between TB-DM and TB-no DM in the proportion of classical, intermediate or non-classical monocyte subsets, however there was a trend towards a lower proportion of classical and higher proportion of non-classical monocytes as glucose control deteriorated (higher HbA1c; Table 1). Female gender and higher BMI were associated with a similar trend. By multivariate analysis this trend remained associated with age and gender (data not shown). Thus, DM2 or glucose control did not appear to influence the distribution of monocyte subpopulations of TB patients.

Table 1.

Relationship between the proportion of monocyte subpopulation, their expression of MN surface markers (MFI) and the host characteristics of TB patientsa

| Diabetes |

Gender |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n=16 | No n=16 | HbA1c | Age | Male n=19 | Female n=13 | BMI | ||||||

| MN populations | n (%) | n (%) | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | n (%) | n (%) | p | Rho | p |

| Classical | 67 (20) | 71 (13) | 0.48 | −0.28 | 0.13 | −0.29 | 0.11 | 75 (16) | 62 (9) | 0.03 | −0.26 | 0.14 |

| Non-Classical | 21 (15) | 17 (11) | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 15 (14) | 25 (10) | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.04 |

| Intermediate | 6 (2) | 7 (5) | 0.40 | −0.21 | 0.25 | −0.08 | 0.66 | 6 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.47 | −0.15 | 0.4 |

| MN MFI | MFI (SD) | MFI (SD) | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | MFI (SD) | MFI (SD) | p | Rho | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (C14++, CD16−) | ||||||||||||

| CD16 | 163 (67) | 161 (72) | 0.94 | −0.08 | 0.65 | −0.16 | 0.39 | 152 (75) | 178 (55) | 0.31 | −0.10 | 0.57 |

| CCR2 | 551 (181) | 430 (120) | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.28 | 441 (125) | 562 (190) | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.91 |

| HLA-DR | 6556 (2395) | 6805 (2712) | 0.78 | −0.13 | 0.46 | −0.1 | 0.58 | 6546 (2727) | 6876 (2276) | 0.72 | 0.13 | 0.47 |

| CD14 | 12137 (8722) | 14003 (9740) | 0.57 | −0.08 | 0.64 | −0.28 | 0.11 | 15500 (9921) | 9519 (6734) | 0.49 | −0.06 | 0.73 |

| CD11b (CR3) | 2585 (318) | 2631 (451) | 0.74 | −0.08 | 0.68 | −0.42 | 0.02 | 2644 (422) | 2557 (333) | 0.54 | −0.23 | 0.21 |

| TLR2 | 2121 (723) | 2236 (717) | 0.66 | −0.19 | 0.30 | −0.05 | 0.79 | 2210 (796) | 2132 (591) | 0.76 | −0.14 | 0.45 |

| TLR4 | 570 (187) | 513 (130) | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 514 (161) | 582 (159) | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.68 |

| CD36 | 2100 (653) | 2252 (1035) | 0.64 | −0.12 | 0.52 | −0.12 | 0.51 | 7972 (17570) | 2017 (686) | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| RAGE | 371 (186) | 315 (182) | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 349 (191) | 334 (177) | 0.82 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| Non-classical (C14+,CD16+) | ||||||||||||

| CD16 | 7691 (2656) | 6880 (1810) | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.57 | 7479 (2147) | 7002 (2508) | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.11 |

| CCR2 | 162 (31) | 176 (41) | 0.29 | −0.11 | 0.55 | 0.1 | 0.58 | 164 (39) | 176 (33) | 0.38 | −0.11 | 0.55 |

| HLA-DR | 10730 (3739) | 11251 (3914) | 0.70 | −0.15 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 11027 (4338) | 10937 (2929) | 0.94 | −0.09 | 0.62 |

| CD14 | 994 (803) | 973 (693) | 0.93 | −0.21 | 0.24 | −0.27 | 0.13 | 1118 (902) | 788 (342) | 0.30 | −0.06 | 0.71 |

| CD11b (CR3) | 407 (393) | 426 (282) | 0.87 | −0.24 | 0.18 | −0.3 | 0.09 | 497 (394) | 299 (188) | 0.10 | −0.14 | 0.44 |

| TLR2 | 2751 (692) | 2680 (740) | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 2833 (796) | 2543 (531) | 0.26 | −0.10 | 0.58 |

| TLR4 | 594 (142) | 615 (130) | 0.66 | −0.12 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 629 (147) | 569 (111) | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.79 |

| CD36 | 197 (65) | 273 (170) | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.55 | −0.14 | 0.45 | 1455 (3102) | 233 (125) | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.34 |

| RAGE | 1349 (578) | 1092 (526) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.60 | −0.02 | 0.91 | 1330 (629) | 1060 (409) | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.01 |

| Intermediate (C14++, CD16+) | ||||||||||||

| CD16 | 3751 (971) | 3518 (977) | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 3574 (1089) | 3723 (784) | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| CCR2 | 380 (117) | 350 (79) | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.62 | −0.1 | 0.59 | 359 (106) | 372 (92) | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.88 |

| HLA-DR | 25845 (6094) | 23036 (5724) | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 24521 (7035) | 24323 (4285) | 0.93 | −0.04 | 0.83 |

| CD14 | 8252 (6288) | 9161 (7295) | 0.70 | −0.09 | 0.61 | −0.35 | 0.049 | 10493 (7633) | 6095 (4081) | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.91 |

| CD11b (CR3) | 2084 (643) | 2180 (651) | 0.68 | −0.16 | 0.40 | −0.28 | 0.12 | 2292 (716) | 1898 (429) | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.89 |

| TLR2 | 3440 (778) | 3807 (1193) | 0.31 | −0.24 | 0.18 | −0.05 | 0.78 | 3843 (1163) | 3302 (639) | 0.13 | −0.17 | 0.37 |

| TLR4 | 1004 (226) | 932 (194) | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 981 (231) | 949 (184) | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.77 |

| CD36 | 1277 (490) | 1602 (821) | 0.21 | −0.12 | 0.51 | −0.12 | 0.51 | 2128 (2343) | 1265 (482) | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| RAGE | 1379 (503) | 1186 (525) | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 1356 (555) | 1176 (452) | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.01 |

Dichotomous variables are expressed as mean values of the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) and standard deviation (SD) of each marker, or the percentage of classical, intermediate or non-classical MNs; Significant values (p< 0.05) are shown in bold with gray highlight and borderline significant (0.05 < p ≤ 0.099) in bold font.

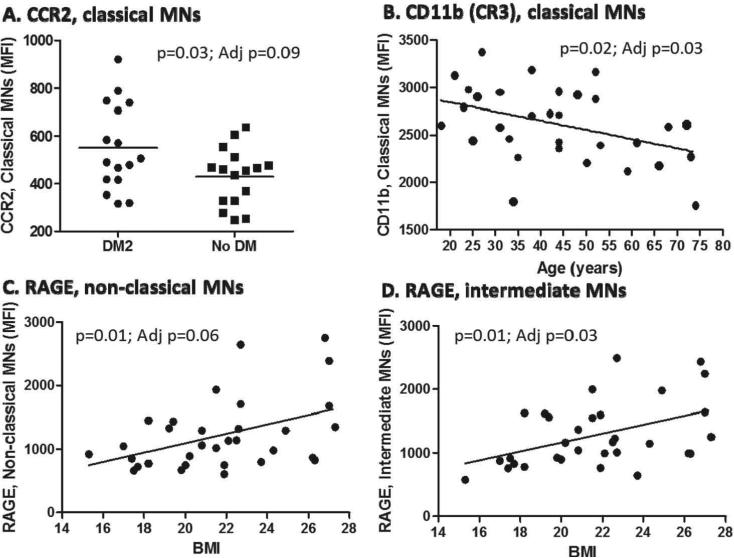

We next evaluated the expression of surface markers important for monocyte trafficking (CCR2), M. tuberculosis entry (CD11b, the alpha chain of complement receptor 3, CR3, or CD16 which is an Fc-J receptor), M. tuberculosis detection by innate immune cells (TLR2, TLR4) and mycobacterial antigen presentation to T lymphocytes (MHC-II).12, 21-23 We also evaluated markers with reported up-regulation in DM2 and that may contribute to M. tuberculosis entry and survival (CD36), or play a potential role in TB pathogenesis (the receptor for advanced glycation end products, RAGE).24-27 By univariate analysis the only differences by DM2 status or HbA1c levels were a higher expression of CCR2 among the classical monocytes or a trend for higher CD16 in the non-classical monocytes, respectively. Older age was correlated with reduced CD11b expression (particularly among classic monocytes) and BMI was positively correlated with RAGE expression. Female gender was associated with higher CCR2 among classical monocytes and lower CD14 and CD11b among intermediate monocytes (Table 1). After controlling for gender, age, BMI and DM2, DM2 remained associated with higher CCR2, older age with lower CD11b, and BMI with RAGE expression (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Graphs of monocyte markers whose expression remained associated with host characteristics after multivariate analysis. Monocytes were gated into sub-populations as described in Figure 1. The relationships between host characteristics and monocyte surface markers are shown for variables that remained significant (p<0.05) or borderline significant (0.05 < p≤ 0.099) after controlling for age, gender, BMI and DM2. The raw and adjusted p values (Adj p) are provided. Horizontal lines indicate means for DM2 and non-DM populations, and linear relationships between continuous variables are shown.

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest that DM2 or chronic hyperglycemia influence the expression of few monocyte markers. However, the higher expression of CCR2 on the monocytes from TB-DM is of interest since it coincides with the reported up-regulation of its ligand CCL2 (MCP-1) in the serum of DM2 patients.28 The in-vivo implications of these findings remain to be determined, but one possibility is that up-regulation of CCR2 may limit the migration of DM2 monocytes from the blood where CCL2 levels are high, to the site of M. tuberculosis infection in the lung and other tissues where these cells are needed most. Interestingly, in mice with DM2 an aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis is characterized by delayed migration of dendritic cells from the M. tuberculosis-infected lungs to regional lymph nodes for T cell priming and this is accompanied by reduced levels of chemokines like CCL2 in lung lysates.29

We anticipated that DM2 would be associated with other monocyte alterations. For example: i) We hypothesized there would be reduced expression of CR3 or Fcγ receptors which are critical for mycobacterial entry into monocytes, given our findings indicating lower association (binding and phagocytosis) of M. tuberculosis with DM2 monocytes.19 However, CD11b levels did not differ by DM2 status and CD16 levels were in fact higher among DM2 patients. ii) We evaluated whether DM2 monocytes had higher MHC-II expression since this could contribute to the enhanced Th1 responses reported in TB-DM patients,6-8 but this was not observed. iii) Studies in TB suggest that CD36 may contribute to M. tuberculosis entry or survival within monocytes, and in DM2 patients this scavenger receptor is up-regulated for uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.24,27,30 Thus we anticipated that increased CD36 in DM2 could contribute to TB susceptibility in DM2 patients, but this was not observed. Finally, iv) RAGE is a scavenger receptor for glycated end products that is up-regulated in DM2 patients, and this receptor may play a role in TB pathogenesis,27,31 but we did not find differences in RAGE expression between study groups. Despite the absence of differences in expression of CD11b, CD16, MHC-II, CD36 and RAGE in baseline blood monocytes of TB-DM versus TB-no DM, it is premature to rule out their contribution to TB susceptibility. That is, their role may not be evident under the conditions evaluated in this study, but their differential expression may be revealed if evaluated in blood monocytes from M. tuberculosis naïve individuals with and without DM2, or in response to invitro stimulation with mycobacterial antigens.

The correlation between age or BMI with the expression of CD11b or RAGE in monocytes, respectively, is of interest given that these two host factors are frequently associated with DM2. Old age is a risk factor for TB and its association with reduced CR3 expression may have implications in TB pathogenesis given the importance of this receptor for M. tuberculosis entry into phagocytes.22,32,33 In contrast, higher BMI may be protective for TB.34 These findings are intriguing because DM2 patients are frequently obese and yet are more susceptible to TB. Thus, further studies are required to elucidate the correlation between RAGE expression and BMI in individuals with and without DM2.

In summary, DM2 was associated with higher CCR2 expression. Thus, this alteration deserves further exploration given the importance of this chemokine receptor for mononuclear cell migration in the lungs and other tissues where M. tuberculosis containment within granulomas is critical. Furthermore, even though DM2, age, BMI and gender were each associated with few phenotype changes in baseline monocytes, the co-occurrence of DM2 with older age and obesity, and the higher frequency of females with DM2 among older populations, can lead to a combination of changes in the monocyte phenotype that have a significant effect on their interaction with M. tuberculosis. Future studies on TB and DM should take into account the individual and interactive effects of these host characteristics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Izelda Zarate from the School of Public Health for field logistics support; Eduardo Olivarez, Lydia Serna, Gloria Salinas and the staff at the pulmonary clinic from the Hidalgo County Health Departments, Dr. Richard Wing from the Texas Department of State and Health Services, Dr. Francisco Mora-Guzman, Olga Ramos, Herminia Fuentes and the staff at the Secretaria de Salud de Matamoros for support with participant enrollment.

Funding

Support for this study was provided by NIH 1 R21 AI064297-01-A1 (to BIR). The NIH had no role in study design, data collection or decision to publish.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: BIR LSS; Performed the experiments: SSS PJM; Analyzed the data: BIR; Wrote the paper: BIR LSS; Approved final version of the paper: all authors.

Ethical approval

Participants signed an informed consent previously approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of the University of Texas Health Science Center Houston, the Texas Department of State and Health Services and the Secretaría de Salud de Tamaulipas.

Competing interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Jeon CY, Murray MB. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of active tuberculosis: a systematic review of 13 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5:1091–101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Restrepo BI. Convergence of the tuberculosis and diabetes epidemics: renewal of old acquaintances. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:436–8. doi: 10.1086/519939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Restrepo B, Fisher-Hoch S, Smith B, Jeon S, Rahbar MH, McCormick J. Mycobacterial clearance from sputum is delayed during the first phase of treatment in patients with diabetes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:541–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, Hart JE, Kapur A, Lonnroth K, et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stalenhoef JE, Alisjahbana B, Nelwan EJ, van d V, Ottenhoff TH, van der Meer JW, et al. The role of interferon-gamma in the increased tuberculosis risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh M, Camerlin A, Miles R, Pino P, Martinez P, Mora-Guzman F, et al. Sensitivity of Interferon-gamma release assays is not compromised in tuberculosis patients with diabetes. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;15:179–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo B, Fisher-Hoch S, Pino P, Salinas A, Rahbar MH, Mora F, et al. Tuberculosis in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: altered cytokine expression in peripheral white blood cells. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:634–41. doi: 10.1086/590565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar NP, Sridhar R, Banurekha VV, Jawahar MS, Nutman TB, Babu S. Expansion of pathogen-specific T-helper 1 and T-helper 17 cells in pulmonary tuberculosis with coincident type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:739–48. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukaguchi K, Okamura H, Ikuno M, Kobayashi A, Fukuoka A, Takenaka H, et al. [The relation between diabetes mellitus and IFN-gamma, IL-12 and IL-10 productions by CD4+ alpha beta T cells and monocytes in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis]. Kekkaku. 1997;72:617–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlesinger LS, Bellinger-Kawahara CG, Payne NR, Horwitz MA. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J Immunol. 1990;144:2771–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:421–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Fingerle G, Strobel M, Schraut W, Stelter F, Schutt C, et al. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibits features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2053–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, Blumenstein M, Strobel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82:3170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serbina NV, Cherny M, Shi C, Bleau SA, Collins NH, Young JW, et al. Distinct responses of human monocyte subsets to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. J Immunol. 2009;183:2678–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chimma P, Roussilhon C, Sratongno P, Ruangveerayuth R, Pattanapanyasat K, Perignon JL, et al. A distinct peripheral blood monocyte phenotype is associated with parasite inhibitory activity in acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000631. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balboa L, Romero MM, Basile JI, Garcia CA, Schierloh P, Yokobori N, et al. Paradoxical role of CD16+CCR2+CCR5+ monocytes in tuberculosis: efficient APC in pleural effusion but also mark disease severity in blood. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:69–75. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1010577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fadini GP, de Kreutzenberg SV, Boscaro E, Albiero M, Cappellari R, Krankel N, et al. An unbalanced monocyte polarisation in peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with type 2 diabetes has an impact on microangiopathy. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1856–66. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez DI, Twahirwa M, Schlesinger LS, Restrepo BI. Reduced Mycobacterium tuberculosis association with monocytes from diabetes patients that have poor glucose control. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013;93:192–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Restrepo B, Camerlin A, Rahbar M, Restrepo M, Zarate I, et al. Cross-sectional assessment reveals high diabetes prevalence among newly-diagnosed tuberculosis patients. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:352–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutledge BJ, Rayburn H, Rosenberg R, North RJ, Gladue RP, Corless CL, et al. High level monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in transgenic mice increases their susceptibility to intracellular pathogens. J Immunol. 1995;155:4838–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlesinger LS. Entry of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into mononuclear phagocytes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;215:71–96. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80166-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quesniaux V, Fremond C, Jacobs M, Parida S, Nicolle D, Yeremeev V, et al. Toll-like receptor pathways in the immune responses to mycobacteria. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:946–59. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkes M, Li X, Crockett M, Diassiti A, Finney C, Min-Oo G, et al. CD36 deficiency attenuates experimental mycobacterial infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arce-Mendoza A, Rodriguez-de IJ, Salinas-Carmona MC, Rosas-Taraco AG. Expression of CD64, CD206, and RAGE in adherent cells of diabetic patients infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch Med Res. 2008;39:306–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Zoelen MA, Wieland CW, van der Windt GJ, Florquin S, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is protective during murine tuberculosis. Mol Immunol. 2012;52:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, Scavini M, Orlando RA, Murata GH, Servilla KS, Tzamaloukas AH, et al. Increased CD36 expression signals monocyte activation among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2065–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panee J. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1) in obesity and diabetes. Cytokine. 2012;60:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallerskog T, Martens GW, Kornfeld H. Diabetic mice display a delayed adaptive immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2010;184:6275–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philips JA, Rubin EJ, Perrimon N. Drosophila RNAi screen reveals CD36 family member required for mycobacterial infection. Science. 2005;309:1251–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1116006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su XD, Li SS, Tian YQ, Zhang ZY, Zhang GZ, Wang LX. Elevated serum levels of advanced glycation end products and their monocyte receptors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Arch Med Res. 2011;42:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlesinger LS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the complement system. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:47–9. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vesosky B, Turner J. The influence of age on immunity to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:229–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leung CC, Lam TH, Chan WM, Yew WW, Ho KS, Leung G, et al. Lower risk of tuberculosis in obesity. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1297–304. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]