Abstract

We analyzed 320 clinical samples of parasitic infections submitted to the Department of Environmental Biology and Medical Parasitology, Hanyang University from January 2004 to June 2011. They consisted of 211 nematode infections, 64 trematode or cestode infections, 32 protozoan infections, and 13 infections with arthropods. The nematode infections included 67 cases of trichuriasis, 62 of anisakiasis (Anisakis sp. and Pseudoterranova decipiens), 40 of enterobiasis, and 24 of ascariasis, as well as other infections including strongyloidiasis, thelaziasis, loiasis, and hookworm infecions. Among the cestode or trematode infections, we observed 27 cases of diphyllobothriasis, 14 of sparganosis, 9 of clonorchiasis, and 5 of paragonimiasis together with a few cases of taeniasis saginata, cysticercosis cellulosae, hymenolepiasis, and echinostomiasis. The protozoan infections included 14 cases of malaria, 4 of cryptosporidiosis, and 3 of trichomoniasis, in addition to infections with Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana, Giardia lamblia, and Toxoplasma gondii. Among the arthropods, we detected 6 cases of Ixodes sp., 5 of Phthirus pubis, 1 of Sarcoptes scabiei, and 1 of fly larva. The results revealed that trichuriasis, anisakiasis, enterobiasis, and diphyllobothriasis were the most frequently found parasitosis among the clinical samples.

Keywords: Parasitic infection, clinical case, incidence, trichuriasis, anisakiasis

Intestinal parasites, for example, Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworms, and Trichuris trichiura were common in Korea until the 1970s. However, these parasites have been steadily decreasing over the last 40 years [1]. In a national survey in 2012, the prevalence of intestinal parasites became 2.6% [2]. In this study, we analyzed not only the intestinal parasites but also extraintestinal parasites detected from clinical specimens submitted to the Department of Environmental Biology and Medical Parasitology, Hanyang University College of Medicine (2004-2011) and compared these results with our previous reports [3].

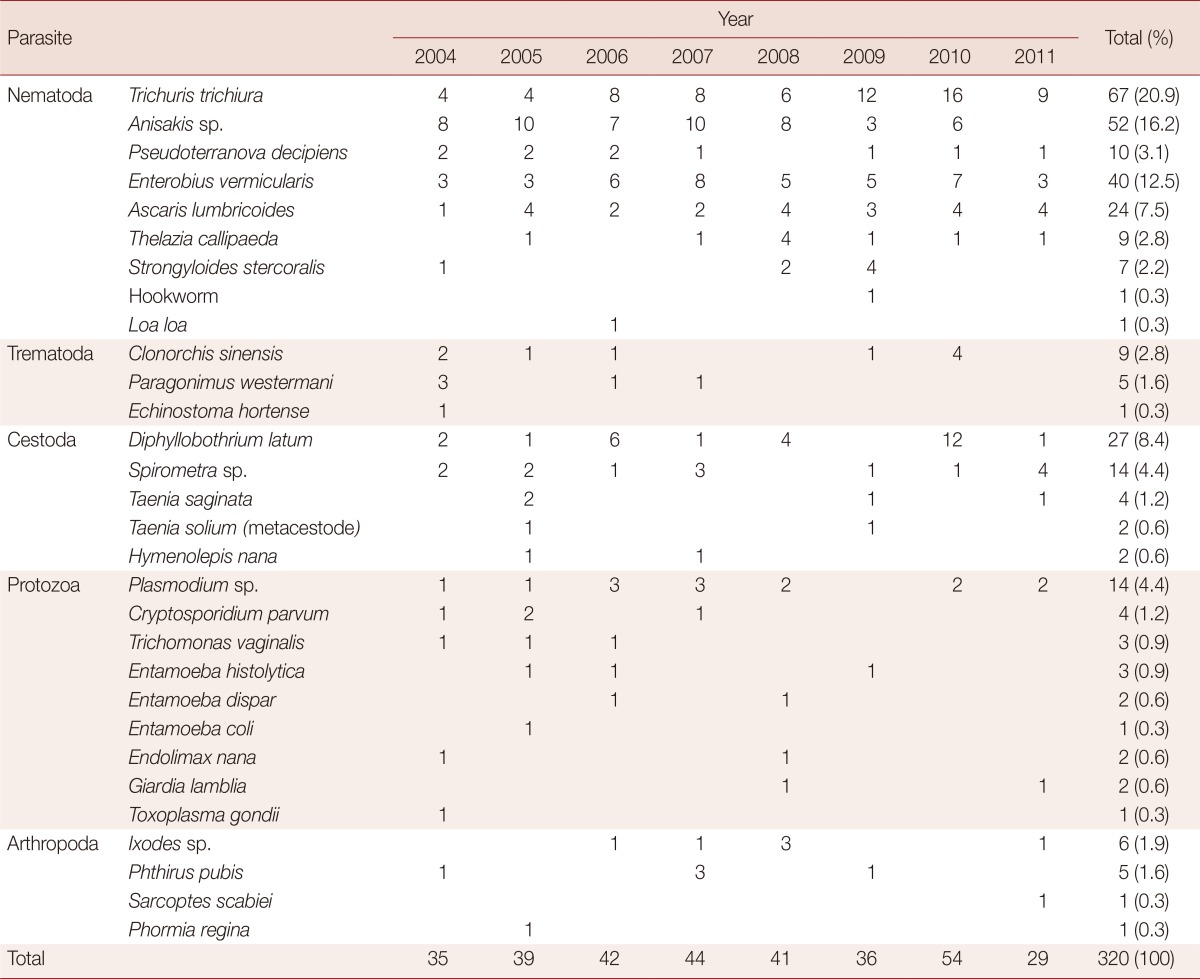

A total of 782 clinical samples were collected, among which we diagnosed 320 cases of parasitic infections from January 2004 to June 2011. Most of these samples were collected from Hanyang University Hospital and 2 commercial laboratories. Parasite infections were detected by the naked eye and microscopic examinations, examination of stools (formalin-ether concentration technique), serologic tests (ELISA), blood smears (Giemsa stain), cello-tape anal swab method, and vaginal swab smears. ELISA was carried out for Paragonimus, sparganum, cysticercus (cellulosae), and Toxoplasma. The clinical materials submitted to our laboratory consisted of 164 parasitic adult worms, 63 larvae, 36 stool samples, 24 proglottids, 14 blood smears, 10 sera, 3 vaginal smears, 2 cello-tape slides, and 3 others. We identified 211 cases of nematodes (9 species), 64 trematodes or cestodes (8 species), 32 protozoa (9 species) and 13 arthropods (4 species). Among the nematode infections, there were 67 trichuriasis, 62 anisakiasis, 40 enterobiasis, 24 ascariasis, 7 strongyloidiasis, 9 thelaziasis, 1 loiasis (imported), and 1 hookworm infection. The trematode or cestode infections included 27 diphyllobothriasis, 14 sparganosis, 9 clonorchiasis, 5 paragonimiasis (ELISA), 4 taeniasis saginata, 2 cysticercosis cellulosae (ELISA), 2 hymenolepiasis, and 1 echinostomiasis (Table 1). Among the protozoa, we diagnosed 14 malaria, 4 cryptosporidiosis, 3 trichomoniasis, 3 amoebiasis, 2 Entamoeba dispar, 1 Entamoeba coli, 2 Endolimax nana, 2 Giardia lamblia, and 1 Toxoplasma gondii (ELISA) infections. Among the arthropods, there were 6 cases of Ixodes sp., 5 of Phthirus pubis, 1 of Sarcoptes scabiei, and 1 fly larva (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Incidence of parasitic infections from 320 clinical samples from 2004 to 2011

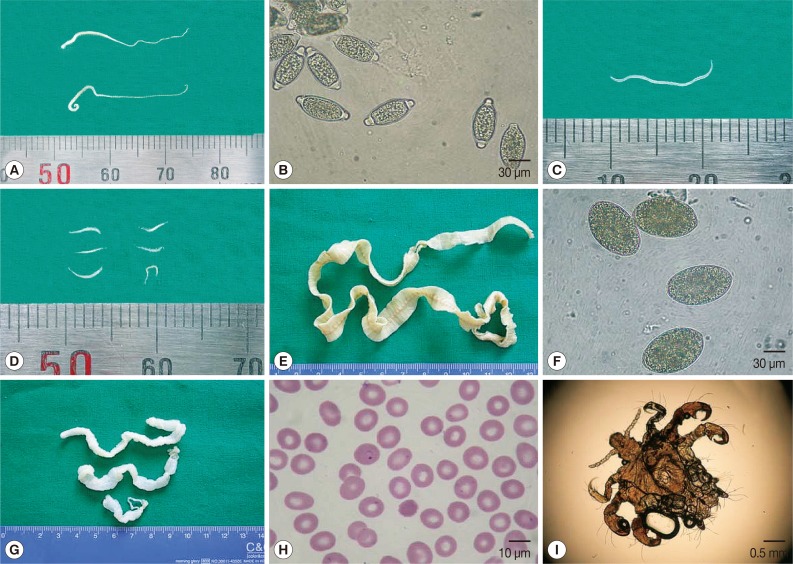

Fig. 1.

The parasites from clinical samples between 2004 and 2011. (A, B) Adult worms and eggs of Trichuris trichiura. (C) Anisakis sp. larva. (D) Adult worms of Enterobius vermicularis. (E, F) Strobila and eggs of Diphyllobothrium latum. (G) Plerocercoids (spargana) of Spirometra sp. (H) Plasmodium vivax. (I) Phthirus pubis.

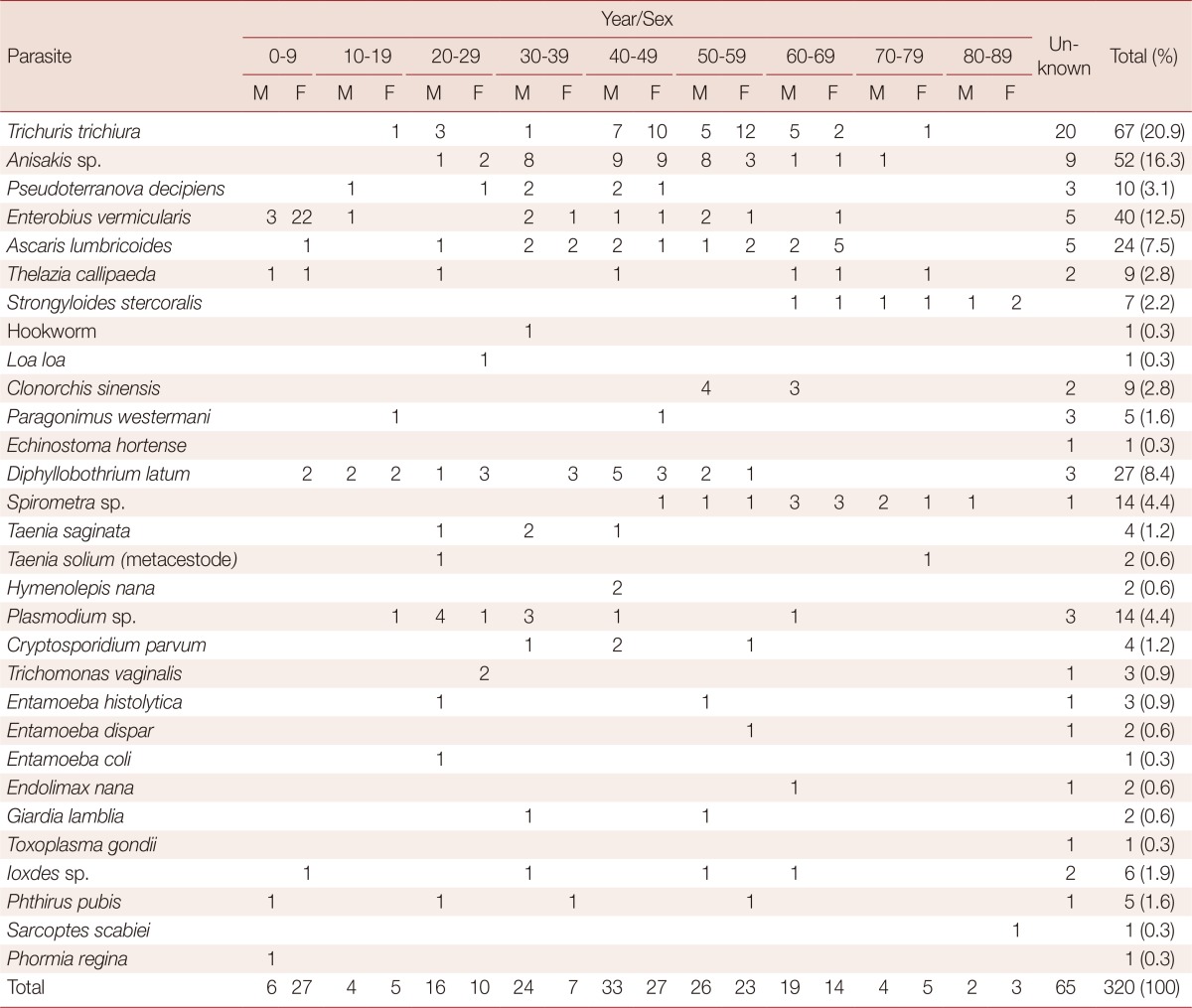

T. trichiura and Anisakis were prevalent among individuals in the 40s-50s, Enterobius vemicularis in 0-9 year-old children, A. lumbricoides and sparganum in individuals in the 60s, Diphyllobothrium latum in people in the 40s, and Plasmodium sp. in patients in the 20s (Table 2). The 3 most common parasites were T. trichiura (20.9%), Anisakis and Pseudoterranova (19.3%), and E. vermicularis (12.5%) (Table 1). Among the trematodes and cestodes, the most frequent parasites were D. latum (8.4%), sparganum (4.4%), and Clonorchis sinensis (2.8%). Among the protozoa, Plasmodium sp. (4.4%), Cryptosporidium parvum (1.2%), Trichomonas vaginalis (0.9%), and Entamoeba histolytica (0.9%) were most commonly observed.

Table 2.

Age and sex distributions of parasitic infections submitted to our Department from 2004 to 2011

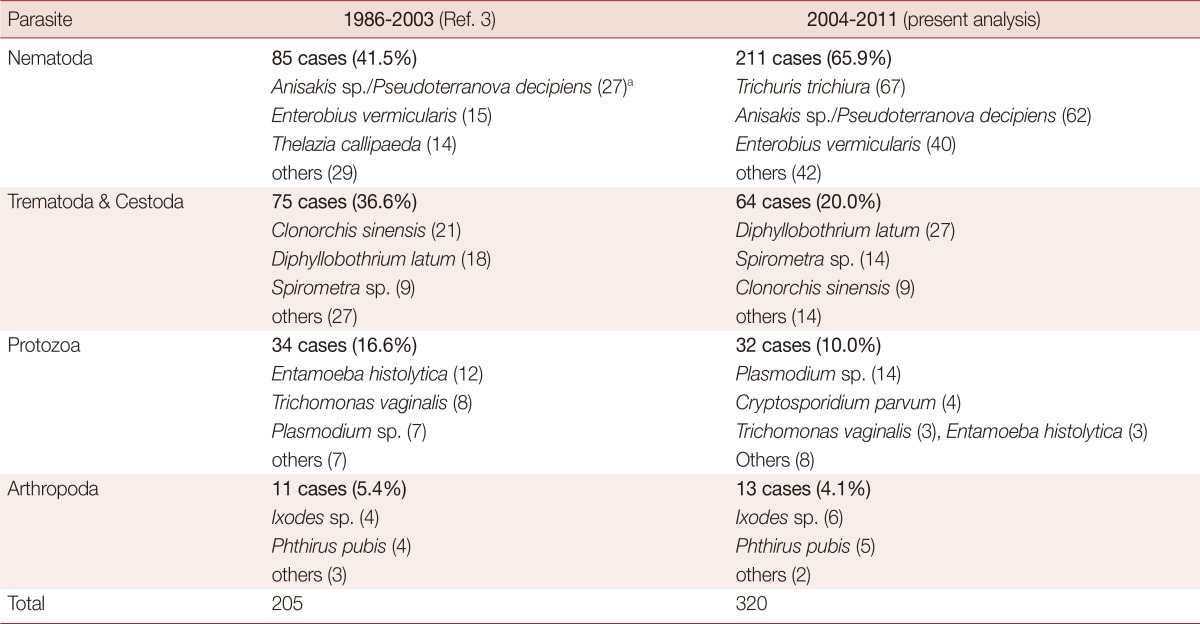

In our previous report [3] describing 205 clinical specimens obtained from 1986 to 2003, Anisakis or Pseudoterranova spp., E. vermicularis, and Thelazia callipaeda in nematodes, and E. histolytica, T. vaginalis, and Plasmodium sp. in protozoa were most common. Among the arthropodes, Ixodes sp. and P. pubis were predominant [3]. In this study, increased nematode and decreased trematode/cestode samples were collected compared with our previous report (Table 3). According to nationwide surveys performed in Korea in 2004 (3.7% egg positive) and 2012 (2.6% egg positive), the most highly prevalent intestinal parasitic infections were C. sinensis (2.4% and 1.9%, respectively) followed by E. vermicularis (0.6% and not done), Metagonimus yokogawai (0.5% and 0.3%), and T. trichiura (0.3% and 0.4%) [2,4]. In 1986, a total of 188 parasite infections (3.6%) were detected among 5,251 stool samples examined in Hanyang University Hospital. Among them, the most common parasite was C. sinensis (75 cases, 1.4%) followed by T. trichiura (37 cases, 0.7%) and E. coli (40 cases, 0.76%) in Seoul, Korea [5]. Another study of intestinal parasites over a 10-year period (2003-2012) reported 14,672 cases of parasite infections (among 429,866 people examined, 3.4%). The predominant helminth parasites were C. sinensis (1.2%) and T. trichiura (0.2%), while non-pathogenic protozoan parasites including E. nana (1.6%) and E. coli (0.45%) were also common [6].

Table 3.

Comparision of common parasitic infections between present analysis and our previous report

aNumber of cases.

Recently, T. trichiura worms are frequently found by colonoscopic examinations [7]. This parasite is a soil-transmitted helminth and its infection occurs via contaminated vegetables or fruits in tropical weather, as a result of poor sanitation, and in areas using human feces as a fertilizer. However, in the present analysis, most of the affected patients had mild Trichuris infections with no symptoms, and the parasite was detected by colonoscopy during health check-up. Anisakiasis is a food-borne parasitic infection, and humans are infected by eating raw or undercooked marine fish or squid [1,8]. This infection is treated by removing the larvae by endoscopy or surgery. Anisakis simplex and Pseudoterranova decipiens are the main species of anisakids reported in Korea. Enterobiasis is common in school-aged children and in this survey, Enterobius infection was also predominant in children. Humans are the only host that can transfer pinworms, and repeated drug therapy or family treatment is needed [1,8].

D. latum infection is acquired by eating raw or undercooked fish. Fish infected with Diphyllobothrium larvae may be consumed in any country in the world. Lately, Diphyllobothrium infection is increasing in Korea, and importation of foods including fish is an important reason for the spreading of food-borne parasitic infections [9,10,11,12]. Most frequent etiologic agents of diphyllobothriasis are D. latum and D. nihonkaiense, however, we did not identify the species of this parasite. Recently, the latter was reported from Japan, Korea, and China. The mitochondrial genome study should be performed for the identification of this tapeworm [13,14]. Sparganosis patients were often encounterd in Korea. The genus Spirometra occurs worldwide, especially in South-east Asia. This parasitic infection is acquired through drinking water containing copepods with procercoid larvae or eating raw or undercooked frogs or snakes. Humans serve as an intermediate or paratenic host for Spirometra spp., and rarely as a definitive host. The most commonly affected site of infection in humans is the subcutaneous tissues, breast, orbit, abdomen, and central nerve system [8]. In this study, the sparganum was removed from the leg, abdomen, breast, thigh, and inguinal regions.

Food-borne trematodiasis is a public health problem in Southeast Asia. The habit of eating freshwater fish and trematode infection are closely related. C. sinensis, the liver fluke, is a cause of cholangiocarcinoma or cholangitis; human infections result from eating raw or undercooked freshwater fish of the family Cyprinidae, containing metacercariae. At present, this parasite infection is quite prevalent (1.9% in 2012) in Korea and a well-known endemic area is found near the Nakdong River, in the southeast of the country [1,8,15]. Fish-borne parasites including clonorchiasis, anisakiasis, and diphyllobothriasis showed high prevalences in this study.

The first reemergence of vivax malaria in 1993 was reported in a soldier working in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) and the reemergence continued for 20 years during which 1,000-4,000 vivax malaria cases were reported annually [16]. Recently, imported malaria has also increased due to abroad travel, and Plasmodium falciparum is predominant among the imported malaria patients. The national surveillance system of the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) detected 808 cases of imported malaria between 1994 and 2012 [17].

Our study demonstrates that some obvious parasitic infections including clonorchiasis, trichuriasis, anisakiasis, enterobiasis, and diphyllobothriasis continue to be prevalent in Korea.

Footnotes

We have no competing interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Ahn MH. Changing patterns of human parasitic infection in Korea. Hanyang Med Rev. 2010;30:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Health. The 8th National surveys on the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections. Seoul, Korea: 2013. pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song HO, Ahn MH, Choi HK, Ryu JS, Min DY, Ree HI. Analysis of 205 cases of parasitic infection confirmed in clinical specimens. Korean J Clin Microbiol. 2004;7:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TS, Cho SH, Huh S, Kong Y, Sohn WM, Hwang SS, Chai JY, Lee SH, Park YK, Oh DK, Lee JK. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in the Republic of Korea, 2004. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:37–47. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min DY, Ahn MH, Kim KM, Kim CW. Intestinal parasite survey in Seoul by stool examination at Hanyang University Hospital. Korean J Parasitol. 1986;24:209–212. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1986.24.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YE, Huh HJ, Hwang YY, Lee NY. A survey of intestinal parasite infection during a 10-year period (2003-2012) Ann Clin Microbiol. 2013;16:134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Do KR, Cho YS, Kim HK, Hwang BH, Shin EJ, Jeong HB, Kim SS, Chae HS, Cho MG. Intestinal helminthic infections diagnosed by colonoscopy in a regional hospital during 2001-2008. Korean J Parasitol. 2010;48:75–78. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin EH, Guk SM, Kim HJ, Lee SH, Chai JY. Trends in parasitic diseases in the Republic of Korea. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai JY. Fish-borne parasitic diseases. Hanyang Med Rev. 2010;30:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee EB, Song JH, Park NS, Kang BK, Lee HS, Han YJ, Kim HJ, Shin EH, Chai JY. A case of Diphyllobothrium latum infection with a brief review of diphyllobothriasis in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2007;45:219–223. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2007.45.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Emerging foodborne trematodiasis. Emerging Infect Dis. 2005;11:1507–1513. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai JY, Murrell KD, Lymberg AJ. Fish-borne parasitic zoonosis: status and issues. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1233–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arizono N, Yamada M, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Ohnishi K. Diphyllobothriasis associated with eating raw Pacific salmon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:866–870. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.090132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SH, Eom KS, Park MS, Kwon OK, Kim HS, Yoon JH. A case of Dipyllobothrium nihonkaiense infection as confirmed by mitochondrial cox1 gene sequence analysis. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:471–473. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn MH, Im KI. Clonorchiasis: clinical cases of Hanyang University Hospital. Hanyang J Med. 1985;5:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joo KH. International travel and imported parasitic diseases. Hanyang Med Rev. 2010;30:156–175. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HS, Kuak J, Yoon SG. Epidemiologic characteristic of imported malaria in Korea, 2003-2012. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2014;7:1–7. [Google Scholar]