Abstract

Introduction

The optimal approach to engage the public in healthcare decision-making is unclear. Approaches range from deliberative citizens’ juries to large population surveys using discrete choice experiments. This study promotes public engagement and quantifies preferences in two key areas of relevance to the industry partners to identify which approach is most informative for informing healthcare policy.

Methods and analysis

The key areas identified are optimising appropriate use of emergency care and prioritising patients for bariatric surgery. Three citizens’ juries will be undertaken—two in Queensland to address each key issue and one in Adelaide to repeat the bariatric surgery deliberations with a different sample. Jurors will be given a choice experiment before the jury, immediately following the jury and at approximately 1 month following the jury. Control groups for each jury will be given the choice experiment at the same time points to test for convergence. Samples of healthcare decision-makers will be given the choice experiment as will two large samples of the population. Jury and control group participants will be recruited from the Queensland electoral roll and newspaper advertisements in Adelaide. Population samples will be recruited from a large research panel. Jury processes will be analysed qualitatively and choice experiments will be analysed using multinomial logit models and its more generalised forms. Comparisons between preferences across jurors predeliberation and postdeliberation, control participants, healthcare decision-makers and the general public will be undertaken for each key issue.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is approved by Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (MED/10/12/HREC). Findings of the juries and the choice experiments will be reported at a workshop of stakeholders to be held in 2015, in reports and in peer reviewed journals.

Keywords: Health economics < HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Introduction

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has recognised the importance of engaging citizens in policy-making.1 Greater participation by citizens can:

Increase the chances of successful implementation of a policy;

Reinforce the legitimacy of the decision-making process and its final results;

Increase the chance of voluntary compliance;

Increase the scope for partnerships with citizens.

Public participation in decision-making can be used in healthcare and for all public goods and services—and is most valuable when used to inform difficult decisions about priority setting and resource allocation.1 Some countries, such as the UK, now routinely seek the views of local people and communities in the assessment of health services and interventions when setting healthcare priorities.2 In Australia, the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission has recommended that a systematic mechanism be developed to formulate healthcare priorities that incorporate community perspectives as well as economic and clinical considerations.3

There are various approaches to seeking the views of the public to inform healthcare decisions. At one end of the spectrum there are deliberative approaches informed by experts, such as citizens’ juries (CJs), in the middle there are lobby groups and consumer representatives in various participatory roles, and at the other end of the spectrum there are referenda where the public vote to either accept or reject a proposal. Less inclusive approaches are opinion surveys of population samples, however, advanced forms of opinion surveys seek to elicit preferences around the attributes that can influence acceptance or rejection of a policy proposal.

The CJs as a deliberative method for engaging the public

In a CJ, a sample of the public are presented with a dilemma about which experts present evidence and are cross-examined by jurors. CJs, as with legal juries, are based on the idea that once a small sample of the population has heard the evidence, its subsequent deliberations can fairly represent the conscience and intelligence of the general public.4 5 CJs are now routinely used by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for health policy guidance, and elsewhere.6 7 There is evidence that jurors become actively engaged in debates, express their views, are able to recall fine details about the information presented and, subsequently, develop a sense of community, shifting their views from self-interested to socialistic.4–7 However, until now, the processes and mechanisms of CJs have been explored qualitatively and there is a need to capture the relative strength of preferences of the individual members of a CJ as well as their consensus opinion.

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) to quantify public preferences for healthcare

CJs do not quantify preferences surrounding healthcare decisions. Quantification of the strength of preference and the trade-offs participants are willing to make between different alternatives before them is important as this information contextualises decision-making. Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) typically involve the presentation of a series of choices between two or more alternative scenarios, each representing a unique combination of specified attributes and levels of the treatment or service under consideration.8 9 Statistical analysis of the individuals’ choices identifies the relative importance of the attributes and the trade-offs individuals make when choosing one scenario over another, (ie, the amount of one attribute they are prepared to forgo to have more of another). Thus, DCEs are a useful approach for quantifying attributes and trade-offs in large samples of the public and can be used in small discrete groups. This study will use DCEs concurrently with CJs in large samples of the public and other relevant discrete groups.

Objective

This paper describes the study protocol of a trial of two distinct processes for engaging the public in healthcare decisions. The specific aims of the study are to:

Determine the preferences of the public for government expenditure in two key areas of healthcare using DCEs and CJs;

Assess the effect of deliberations in the CJ on preferences for healthcare using DCEs;

Assess the test–retest reliability (stability) of preferences elicited from DCEs;

Identify and evaluate the discursive processes that characterise CJs;

Identify the correlation between preferences of jurors after deliberations, and healthcare decision-makers.

Methods and analysis

A mixed methods approach to eliciting public input for healthcare decision-making will be used. The study will adopt qualitative (CJ processes) and quantitative (DCE) approaches. Following consultation with the industry partners, two key areas of relevance were identified for this study; namely how to optimise use of emergency care and prioritising patients for bariatric surgery. For each key area, a CJ will be conducted and DCEs undertaken in the jurors, a control group, healthcare decision makers and a large sample of the general public.

Health topics for the study

1. Optimising appropriate use of emergency care: emergency department (ED) crowding is a global as well as national challenge. If unchecked, it can result in poor health outcomes.10 11 Strategies to address crowding can be found at all levels of the health system from prehospital to community care.10 11 The problem of crowding in EDs is not independent of the challenge of reducing elective surgery waits, as both result in competition for inpatient beds.11 Public input into the planning, promotion and implementation of strategies to reduce the inappropriate utilisation of EDs and the allocation of resources to address crowding would contribute to efficient and responsive policy in this area. The DCE will quantify trade-offs the public is prepared to make between the key characteristics of an emergency service differentiated according to the severity of condition (eg, waiting times, clinician versus nurse led consultations, service location, hospital or primary care clinic setting) which will inform the development of strategies for optimising appropriate ED utilisation.

2. Prioritising patients for bariatric surgery: The increasing prevalence and health and economic burden associated with obesity are well established.12 13 A range of interventions are available to reduce obesity, some of which have good evidence supporting their effectiveness.14 There are a number of controversial issues for deliberation around this elective surgery (eg, what criteria should be used to prioritise access? Should any population subgroup/s receive priority?) A DCE will be designed to quantify the relative importance of and implied trade-offs between priority-setting criteria for surgical management of obesity.15–17

Refining the topics for study

Key staff members from Queensland Health (QH) will be selected to form focus groups. One focus group will be held for each topic, with different staff members being selected to participate in each group. The lead partner investigators in QH will nominate approximately 15 staff for each focus group, according to their expertise and experience in the broad topic area. The focus groups will develop specific questions to be addressed by the CJs and DCEs. These questions will be reviewed and amended as necessary by the partner investigator to ensure they have direct policy relevance. The focus groups will be conducted using the nominal group technique (NGT) which is a multistage method designed to assist a group to reach agreement about issues and key priorities in order of importance.18 19 The NGT process begins with nomination by individuals of key issues that affect a particular area, group discussion for clarification and refinement followed by a structured ranking and voting task in which participants individually select their top five issues. Further discussion elucidates the details contained within each issue, enabling attributes and levels to be understood and articulated during analysis. This method meets the recommendations of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research as outlined in the Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force as will be discussed later.20

The jury process

One jury will be selected to address each health issue. Both issues will be deliberated using a CJ in Queensland and one CJ will be developed in South Australia (SA) to assess consistency in a different sample. The jury process will be closely aligned with the process espoused by the Jefferson Center,21 including juror selection, witness selection, providing the jury with a ‘charge’ (task facing the jury), planned hearings, breakout periods for deliberations and deliberative period for developing recommendations.

Samples of approximately 20 members of the general public will be recruited for each CJ. Expert witnesses will include patients and/or carers, clinicians, health professionals (eg, doctors, nurses and allied health) and health service managers. These witnesses will be identified and provided by the partner investigators to cover the fields of expertise for each topic in Queensland and SA. With a facilitator, the jury will be charged with their task, and hear and question expert witnesses presenting evidence on the relevant topic. Warm-up exercises, ground rules, introduction to the topic and background will be covered in an initial session. Scenarios about the topic will be presented to the jurors for a priority-setting ranking exercise. Following this exercise, expert witnesses will present their view on the topic and jurors will question each witness following their presentation. Small groups of 3–4 members will engage in discussions around focused questions including the criteria for priority setting. A set of recommendations on priorities will be developed from each CJ, and these recommendations will be presented to the partner organisations.

The DCEs

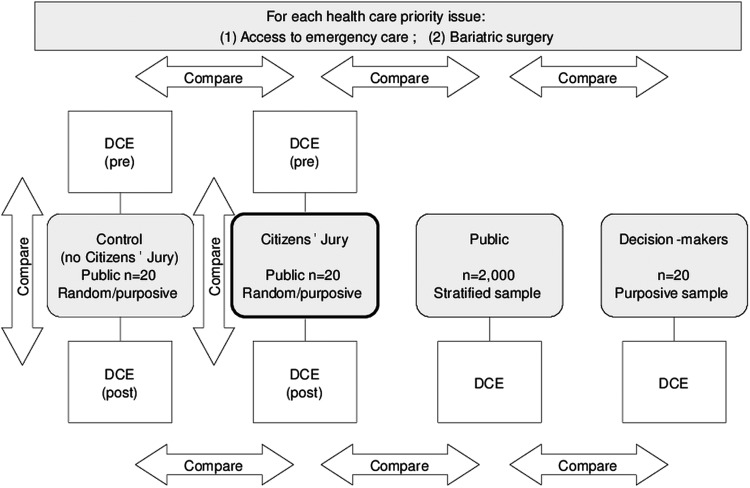

A DCE will be developed for each deliberative issue. This will be presented to four independent groups: (1) the jurors; (2) a control group; (3) a group of decision-makers and (4) a large random sample of the general public. DCEs will be presented to these four groups in Queensland and to the jurors, decision-makers and general public in SA. This will enable comparisons between different populations (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design for each issue deliberated.

Each juror will undertake the DCE immediately prior to start of the jury to measure the strength of their personal preferences. The same DCE will be presented to the jurors at the end of the jury, and at approximately 1 month following the jury to determine if preferences have changed. Using the same sampling frame used to select jurors (see below), a group of individuals not involved in the deliberations will also be given the DCE at the same time points. This will determine test–retest reliability of the DCE without the intervening deliberation and identify any effects of ‘learning’ to be accounted for when analysing preferences. A sample of decision-makers, such as clinicians or budget holders will be given the same DCE at the same time points. A larger and wider representative population-based sample will also be presented with the DCE using a web-based survey format to ascertain the preferences of the general public. Overall, this series of DCEs will enable comparisons to be made between the juries, individual consumers, the general public and decision-makers in two Australian states.

Development of the DCEs

Guidelines on DCEs outline the key principles for good practice in eliciting preferences using DCEs.8 22 There are four key steps in developing a DCE:

1. Selection of attributes: The NGT process described above will be used to reach consensus in samples of the health-informed population (ie, n=12 health professionals/general public per group) about the key factors (attributes) associated with each problem area. Once the attributes for each issue are identified they will be ranked in order of priority.23

2. Refining attributes and levels: Discussion facilitated during the NGT will be used to confirm attributes and levels, establish the levels of each attribute and develop consumer friendly wording which will be used in the DCE.

3. Experimental design of the DCE: Subject to the outcome of the NGT, respondents will be asked to imagine they are the decision-makers for allocating resources to address a health problem within the next year, and to choose between two options. Various attributes and levels will form the basis of the self-completed DCE questionnaire. An illustrative example of a choice that could be used to develop priorities related to elective surgery is illustrated in table 1.

Table 1.

Example of a discrete choice experiment for bariatric surgery

| Individual A | Individual B | |

|---|---|---|

| Current level of obesity | Obesity (BMI 30 to less than 40 kg/m2) | Very severe obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2) |

| Diagnosed with type 2 diabetes | No | Yes |

| Age of person needing surgery (years) | 50 | 35 |

| Effectiveness of surgery for weight loss at 2 years (%) | 70 | 50 |

| Failure to respond to prescribed lifestyle intervention | No | Yes |

| Time spent on waiting list | 2 years | 6 months |

| Who should have their surgery now? | Individual A □ |

Individual B □ |

BMI, body mass index.

An optimal experimental design will be generated for the DCE to maximise the D-efficiency and minimise SDs8 22; a main effects fractional factorial design will be used for the small samples (eg, jurors) and a ‘blocked’ full factorial design for the large population sample (ie, several versions of smaller choice sets will be developed and respondents will be randomly assigned to each version). One of these blocks will be the main effects block, identical to the DCE for the smaller samples, to enable testing of consistency of preferences between jurors and the general population when presented with same choice scenarios. The final DCE design will depend on the final number of attributes and levels.

4. Piloting the questionnaire: The DCE will be piloted to inform the design and administration of the main survey.

Sample size

Each jury will consist of 20 jurors; this is the minimum recommended sample size to undertake an analysis of main effects of a DCE using methods such as multinomial logit modelling.8 Sample sizes of approximately 20 for the control groups and for the healthcare professionals/decision-makers will also be used. For the large general population DCE, the number of attributes and levels within the full-factorial experimental design will determine the sample size required. Thus, the final number of participants for this DCE cannot be specified exactly until the DCE is defined. Based on the adult population of Australia and assuming evenly divided preferences, a sample of 500 has a margin of error (MoE) of 4.4% that decreases as sample size increases; a sample of 3000 has a MoE of 1.8%.24 Owing to the relative ease of web-based recruitment, this will continue throughout the study until the minimum sample necessitated by the design of the DCE is achieved. For each DCE, at least 2000 respondents will be recruited to ensure sociodemographic representativeness relative to the general Australian population.

Recruitment

A combination of random sampling and purposive sampling will be used.6 Each jury will have different jurors. Based on response rates of 2–25%, to obtain a representative sample of 20 jurors in Queensland and another 20 as a control group, 4000 people will be randomly sampled from the electoral roll in Queensland for the CJs in Queensland and those who respond to newspaper advertisements in Adelaide, SA.

For the jurors, a letter of invitation, jury explanation, jury dates and questionnaire to screen for basic demographic factors will be sent to the identified person. The questionnaire will seek age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, employment status, number and age of dependents and affiliations with special interest groups (exclusion) or employment as a healthcare professional (exclusion). To reduce volunteer bias, a sitting fee will be offered (in addition to travel and accommodation expenses) to jurors. On return of the surveys, eligible respondents will be categorised into groups to approximate the demographic profile of Queensland. Where there is more than one case for each demographic category, the participant will be randomly selected from that category. Those not selected for the initial jury may be selected for the DCE control group or for a subsequent jury. The DCE-only control group will be purposively selected and a 100% response rate will be important; therefore, they will be incentivised on a fixed fee basis for returning their surveys.

For the piloting of the DCEs, convenience samples will be recruited from staff and students at Griffith University through local advertising and incentives. The final DCEs will be sent to identified decision-makers and key clinical staff in QH and SA Health. The DCEs will also be sent to a large sample of the general population through a web-based survey. Although there is potential for selection bias in web-based surveys, bias between variables in preference elicitation studies is minimal and general population panel-based web surveys have been shown to be valid and reliable.25 26 Email invitation will be sent to a stratified sample from PureProfile (http://www.pureprofile.com/au). PureProfile is an opinion seeking company with a large panel of research participants.

Analysis of the data

Qualitative analysis

The CJ will be analysed qualitatively to assess discourse within the jury process and experiences of jurors. Thematic and discursive analysis will be employed to examine the qualitative data (ie, transcribed recordings of jury deliberations and interviews with a purposively selected sample of jurors from each CJ prior to and following deliberations). Multiple waves of coding will be applied by at least two independent coders to increase integrity. As thematic analysis is open to interpretation, a systematic process will be used for (1) initial coding of verbatim transcripts at the paragraph level, (2) clustering of codes to develop concepts, (3) developing themes from concepts to explain the majority and (4) explaining deviations. Several critical frameworks will be applied to these themes. First, data will be organised according to a matrix, enabling data to be compared across time, topics and populations. Given the importance of change over time in this study, process mapping will be used.27 Process mapping is a simple tool often used in the service improvement area to capture a journey or movement over time (planning and decision-making processes, change in juror experiences). Maps also identify constraints, pathways and triggers and can document change by comparing maps generated at different points in time or place. Semistructured interviews with jurors will examine experiences of the CJs, capacity to engage, decision-making processes and changes in beliefs about healthcare. A benchmark for this qualitative data, including its limitations, has been set by the NICE deliberations and evaluation.4 Finally, a feedback questionnaire with a Likert scale will be developed for jurors to complete at the end of the jury session; this will explore issues such as the difficultly of the task, the number of witnesses, the scope and depth of information presented and usefulness of small discussion groups.

Statistical analyses

Data from the DCE will be analysed using dichotomous choice models such as mixed logit regression or generalised multinomial logit. Mixed logit models allow for correlation of error components within subjects, as well as correlation between alternatives where there is more than one alternative. Mixed logit also allows for unobserved heterogeneity that can be examined by specifying random parameters (ie, separate coefficients for each individual).28

Marginal rates of substitution (MRS), calculated as the ratio of attribute coefficients, will be used to assess the relative importance of the attributes and the trade-offs respondents are willing to make between attributes for gains in another attribute. Preferences will be compared across discrete choice models (eg, decision-makers vs public, prejury vs postjury) using two methods: (1) using correlations of the model coefficients29 and (2) by comparing the predicted MRS between attributes.

Ethics and dissemination

Funding was awarded by the Australian Research Council through a Linkage Grant (#LP100200446), with financial contributions from QH and SA Health. Findings of the juries and the choice experiments will be reported at a workshop of stakeholders to be held in 2015, reports to the funding partners, conference presentations and in peer reviewed journals.

Outcomes from this research include direct recommendations for priority setting from the deliberations of the juries on the three critical issues under consideration. It will also provide recommendations and knowledge about the processes of consumer engagement which challenge many governments across the world.

Although CJs are used in the UK and Canada, use of CJs for healthcare in Australia is relatively limited.30 It is unclear as to whether this method would work in more dispersed urban and rural settings as are found in Australia. This study provides substantial impetus for the development of a systematic consumer engagement framework for healthcare priority setting. In the long-term, this project will have a substantial impact on processes of decision-making, priority setting and public participation in Australia.

This study is one the first to combine DCE methods with a CJ. Studies on consumer input into decision-making have adopted either a qualitative or quantitative approach31; the use of both approaches is a logical, but to date underutilised, combination. An innovative component of this study is to undertake DCEs on members of a CJ before the jury meet, and then after deliberations to explore the effect of the CJ process on preferences and choices. This design will allow us to determine whether the preferences of individuals in isolation lead to the same decision made following an interactive group process. Moreover, it will allow us to compare preferences and decisions made before and after participants are fully informed about these complex issues. Thus, we will be able to make conclusions about the impact of information and its presentation on preferences.

Very few studies have compared decision-makers’ choices with those of the general public.32 This study will systematically undertake comparisons to identify whether decision-makers adequately represent the views of the public. Finally, the study will test the utility and reliability of the DCE over time, which is essential to the validation of its use in this context.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the in-kind support from these organisations and from other partner organisations including Queensland University of Technology, University of Sydney, Flinders University and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the study design, the grant application and the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. PAS initiated the idea, led the grant application and drafted this manuscript. JAW and JR led the design of the choice experiments, PB led the design of the juries and EK led the focus group design. AW, PL, KC, EK and PAS gave input into the design of the juries, and all authors gave input into the design of the choice experiments.

Funding: This work was supported through an Australian Research Council Linkage Project, grant number LP100200446. Additional financial contributions were received from Queensland Health and South Australia Health and Central Adelaide and Hills Medicare Local.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study is approved by Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (MED/10/12/HREC).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Caddy J, Vergez C. Citizens as partners:information, consultation and public participation in policy-making. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Street JM, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Facey K, et al. Virtual community consultation? Using the literature and weblogs to link community perspectives and health technology assessment. Health Expect 2008;11:189–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. A Healthier Future for all Australians: Final Report. Canberra: Australian Government, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies C, Wetherell M, Barnett E, et al. Opening the box: evaluating the citizens council of NICE. Milton Keynes: The Open University, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iredale R, Longley M, Thomas C, et al. What choices should we be able to make about designer babies? A citizens’ jury of young people in South Wales. Health Expect 2006;9:207–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon D, Stafinski T. Engaging the public in priority-setting for health technology assessment: findings from a citizens’ jury. Health Expect 2008;11:282–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers WA, Street JM, Braunack-Mayer AJ, et al. Pandemic influenza communication: views from a deliberative forum. Health Expect 2009;12:331–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanscar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform health care decision making. A user's guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003; 2:55–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. Access block and overcrowding in emergency departments. 2004. https://www.acem.org.au/getattachment/56688d18-4f4c-467a-bba3-704d994d9f2d/Access-Block-2004-literature-review.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, et al. Emergency department crowding, part 1—concept, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:605–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. The burden of overweight and obesity in the Asia-Pacific region. Obes Rev 2007;8:191–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, Berghofer A, et al. Health-economic burden of obesity in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker P, Young M. Summary of evidence—systematic reviews: obesity. Secondary Summary of Evidence—Systematic Reviews: Obesity 2006. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/ph/documents/caphs/32117.pdf

- 15.Jan S, Mooney G, Ryan M, et al. The use of conjoint analysis to elicit community preferences in public health research: a case study of hospital services in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2000;24:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan M, McIntosh E, Dean T, et al. Trade-offs between location and waiting times in the provision of health care: the case of elective surgery on the Isle of Wight. J Public Health Med 2000;22: 202–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Zapata LI, Alvarez-Dardet C, Ortiz-Moncada R, et al. Policy options for obesity in Europe: a comparison of public health specialists with other stakeholders. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:896–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delbecq A, VandeVen A. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J Appl Behav Sci 1971;7:466–91 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiligsmann M, van Durme C, Geusens P, et al. Nominal group technique to select attributes for discrete choice experiments: an example for drug treatment choice in osteoporosis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:133–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bridges J, Hauber A, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Jefferson Center. Citizens jury handbook. 2004. http://jefferson-center.org/what-we-do/citizen-juries/ (accessed 2 Apr 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. The Netherlands: Springer, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones A, Hunter D. Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wonnacott TH, Wonnacott RJ. Introductory statistics. 5th edn New York: Wiley, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damschroder LJ, Baron J, Hershey JC, et al. The validity of person tradeoff measurements: randomized trial of computer elicitation versus face-to-face interview. Med Decis Making 2004;24:170–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etter J-F, Perneger TV. A comparison of cigarette smokers recruited through the Internet or by mail. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:521–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butterfoss F, Goodman R, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res 1993;8:315–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjaer T, Gyrd-Hansen D. Preference heterogeneity and choice of cardiac rehabilitation program: results from a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy 2008;85:124–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall J, Fiebig D, King M, et al. What influences participation in genetic carrier testing? Results from a discrete choice experiment. J Health Econ 2006;25:520–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mooney GH, Blackwell SH. Whose health service is it anyway? Community values in healthcare. Med J Australia 2004;180:76–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitty JA. Public and decision-maker preferences for pharmaceutical funding: an Australian Discrete Choice Experiment. School of Medicine, Griffith University, 2008 [Google Scholar]