Abstract

Objective. To quantify the impact of pharmacy students’ clinical interventions in terms of number and cost savings throughout advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) using a Web-based documentation program.

Methods. Five hundred eighty doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students completing ten 4-week APPEs during the final year of the curriculum were asked to document all clinical interventions they made using a Web-based documentation tool. Data were collected over 4 academic years.

Results. The total number of interventions made was 59,613, the total dollars saved was $8,583,681, and the average savings per intervention was $148. The top 3 categories of interventions made by students were identifying dosing issues, conducting chart reviews, and recommending appropriate therapy. The top 3 intervention types made by students that resulted in the most dollars saved per intervention were identifying potential allergic reactions, identifying drug interactions, and resolving contraindications.

Conclusions. Pharmacy students made important and cost-effective clinical interventions during their APPEs that resulted in significant savings. Documentation programs can track the number, type, and value of the interventions that pharmacy students are making.

Keywords: pharmacy student, clinical interventions, cost analysis, APPE, experiential education

INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges facing many colleges and schools of pharmacy is finding enough experiential sites and preceptors to train students during practice experiences.1,2 This is more difficult than it was a decade ago for several reasons. There are more pharmacy colleges and schools today and they are enrolling students who will all need to complete IPPEs and APPEs. Introductory pharmacy practice experiences are now a requirement for all colleges seeking accreditation.3 There is also a higher demand for residency programs.4 As more practice sites try to meet this need, it places additional pressure on preceptors to continually mentor more people, be it IPPE students, APPE students, or residents.1 However, pharmacy students are capable of providing meaningful clinical services for the practice sites and can generate financial savings, which have been well documented in the literature.5-16 Mersfelder and Bouthillier published a review of these studies dating back to the early 1990s.17 Most either enrolled few students or were conducted over a relatively short period of time, often just a few months. Some studies were limited in terms of experience type or practice sites and only tracked interventions made during inpatient experiences or in critical care environments at specific institutions. Other studies did not include a financial assessment and only looked at the number of interventions made by students and acceptance rates by the primary care providers. This report expands upon the existing literature and provides more evidence to support the value of pharmacy students during APPEs. It includes 4 years of student interventions over various practice settings and experience types and provides more detailed information about the clinical interventions made by students. The interventions were documented through a commercially available Web-based documentation program. The most common student interventions as well as the most economically valuable interventions are presented and discussed. The objective of this study was to quantify the impact of pharmacy students’ clinical interventions in terms of number and cost savings throughout advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) using a Web-based documentation program.

METHODS

For the past 4 years, each PharmD class of approximately 160 students (580 total students participated) were asked to document their clinical interventions during their APPEs in the fourth year of the degree program. Each student completed 10 consecutive 4-week APPEs beginning in May and finishing in April. They were not assigned to an APPE during three 4-week blocks during this year. At least 7 of the 10 APPEs they completed were required patient care APPEs. Patient care APPEs were in ambulatory care practice, inpatient adult medicine or specialty practice, community pharmacy practice, or hospital health-system pharmacy practice.

Prior to beginning their APPEs, students were trained to use Clinical Measures (Elsevier/Gold Standard), a Web-based documentation program purchased by the college.18 This documentation program was primarily designed for use by health systems as a way of tracking clinical pharmacist interventions on a regular basis. By entering the students’ names in as pharmacists and entering the physician’s name in place of the practice site, the software was easily modified to collect data on student interventions at any practice site during any APPE. It also did not require patient-specific data to be entered, only information about the specific intervention made. Preceptors were able to check these interventions after the students entered them. The system was reasonably priced (approximately $3500 per year). One of the most impressive features was the ability to generate reports quickly and easily as PDFs that could illustrate student interventions and cost savings. Other similar Web-based systems such as Quntifi and PxDx have been used at other institutions.15,16 The documentation program allowed students to enter the type of intervention made and whether it was accepted by the primary health care practitioner. The program would then calculate a cost savings based on the intervention type and the drug involved. A list of available intervention types with major categories and subcategories is available from the author. The software program kept a running total of each student’s interventions, the acceptance rates, and the total dollars saved throughout the year. At no time were any patient-specific data collected. Only information regarding the type of clinical interventions made was documented and the associated cost savings were measured. Students were encouraged to document all interventions but were not required to do so. The retrospective evaluation of this student data for publication purposes was submitted to the university’s Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt.

The Clinical Measures program calculated cost savings based on the direct costs that would have been incurred had the potential adverse outcome not been prevented using cost saving/cost avoidance estimates from primary and tertiary literature sources. Clinical Measures also used ProspectoRx to establish drug pricing using the calculated average wholesale price (C-AWP) and average wholesale price (AWP) when the C-AWP was unavailable.19 For instance, when an intervention, eg, conducting a chart review, was not tied to a specific drug, an hourly rate for pharmacist wages was used and multiplied by the time spent on the activity. (A list of references used for cost verification by the software company is available from the author upon request.)

RESULTS

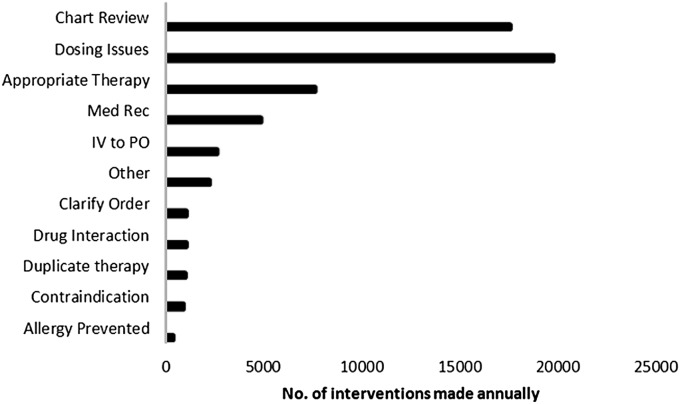

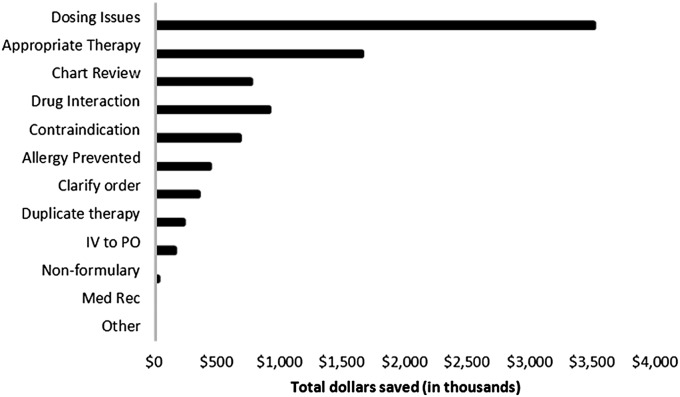

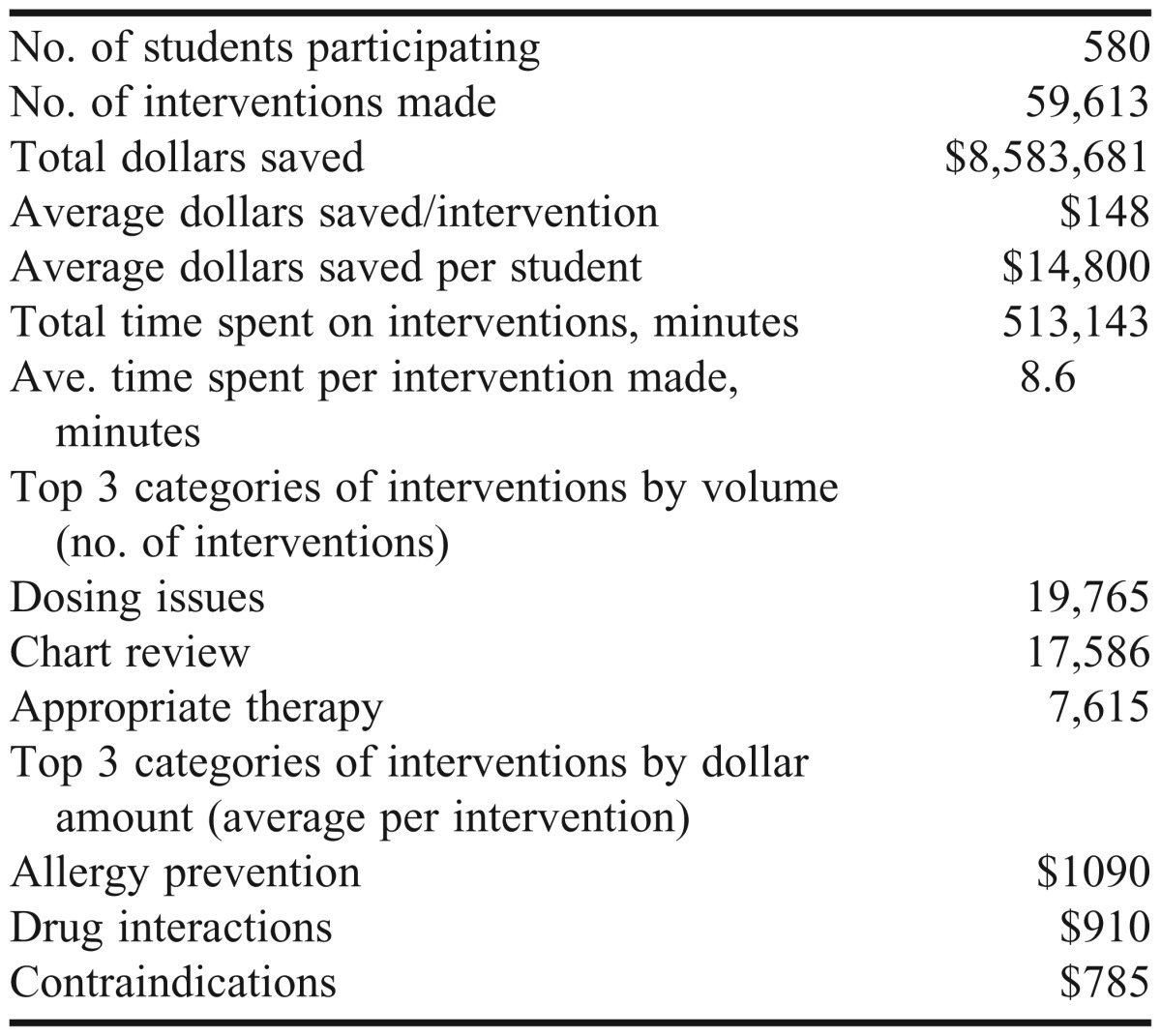

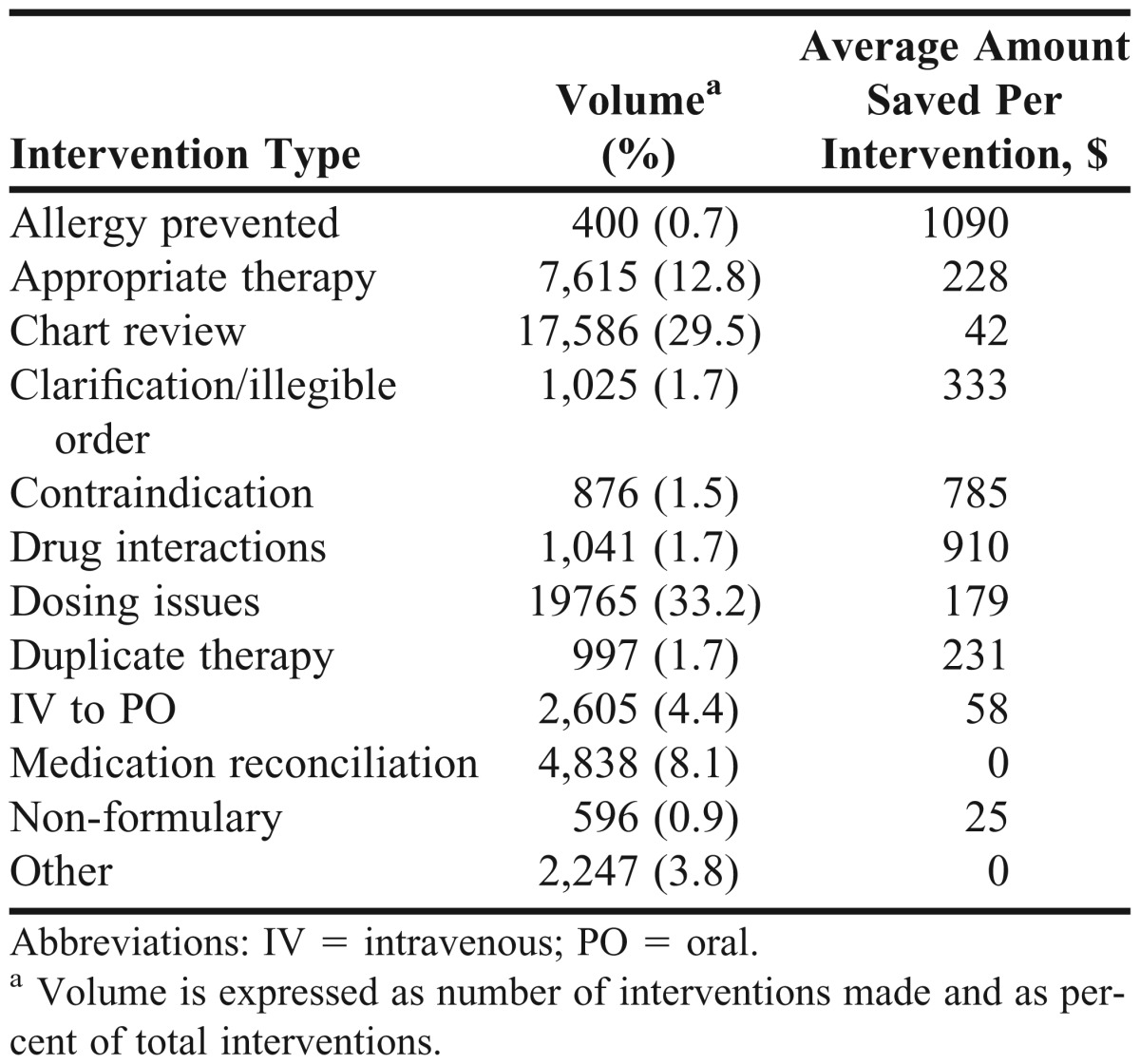

The number of students participating from each class from 2009-2013 ranged from 134 to 156 per year. The total number of interventions documented in Clinical Measures during this 4-year period was 59,613 (Figure 1) and represented a total cost savings of $8,583,681 (Figure 2). The average dollars saved per student intervention was $148. Students spent 513,143 minutes making interventions, or an average of 8.6 minutes per intervention (Table 1). The most common interventions made by pharmacy students were conducting chart reviews, fixing dosing issues, and ensuring appropriate therapy with preceptor approval. These interventions were consistently the top 3 student interventions made every year. Prevention of allergic reactions, identification of potential drug interactions, and resolving contraindications netted the most dollars saved per individual intervention, but these interventions were not those most frequently documented by students. Interventions to prevent allergic reactions, for example, made up only 0.7% of the total pharmacy student interventions (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Pharmacy student interventions by total volume during advanced pharmacy practice experiences.

Figure 2.

Pharmacy student interventions by total dollars saved during advanced pharmacy practice experiences.

Table 1.

Summary Data From a Study of Cost Savings Associated With Pharmacy Student Interventions During Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences

Table 2.

Volume and Average Dollars Saved per Intervention by Pharmacy Students During Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences

DISCUSSION

Pharmacy students made valuable clinical interventions during their APPEs that translated into financial savings. The total dollar amount saved in this study was only an estimate and is subject to some limitations. Some medications were not available to document in Clinical Measures. This was especially true for any new medications that had been approved but had not been added to the software program yet. In such cases, the pharmacy student was unable to record the intervention. Also, the dollars saved were not specific to any particular practice site or institution. Therefore, the documented savings by each pharmacy student at any given practice site served as an estimate of the financial benefit of precepting students in general. There was some variability in findings between each class and between students because of differences in APPE schedules. Every student was required to complete at least 7 patient care APPEs, but some students may have chosen patient care experiences for all 10 of their APPEs. The students who completed 10 patient care APPEs would have had more opportunities to document clinical interventions compared to students taking non-patient care elective APPEs. Even with these differences, the percentages of intervention types made by students across all 4 years appeared similar, with dosing issues constituting about a third of all interventions made each year (ie, 32.3%, 36.2%, 31.7%, and 32.9% respectively for the 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012 years); however, direct comparison of student performance in individual years was not an objective of this study.

Previous studies have included a projected cost for training students during APPEs. Brockmiller et al7 calculated the monthly pharmacist’s salary and average number of hours per month devoted to precepting in order to obtain a reasonable estimate of training costs. Using a similar method and the current hourly wage for pharmacists from the Bureau of Labor and Statistics of $55.27, it would cost a preceptor $1,113.40 to precept 1 student for a 4-week APPE.20 This figure is based on the assumption that the preceptor spends 20 hours per month directly supervising the student, which is the minimum amount of time expected of preceptors in our program. It is also consistent with the published average number of hours required to precept a student on a 4-week APPE.21 This figure could vary greatly depending on the type of APPE and practice setting and the student being supervised. Preceptors in the critical care environment, for example, may spend far more time training students each week. Brockmiller used an estimate of 58.8 hours per month.7 If students make approximately $148 per intervention, they would need to make 8 interventions during their 4-week APPE if the preceptor was spending 20 hours per week with them, and 22 interventions if the preceptor was spending 58.8 hours with them in order to justify the cost of precepting. From the numbers presented, the average dollars saved per student would be approximately $14,800. However, the number of interventions made by any given student appears to vary greatly. For example, in the 2012-2013 data set, the total dollars saved per student per year ranged from $329 to $180,769 (data not shown). Some students either made more interventions than others or were better about documenting the interventions they made. The real benefit to preceptors and practice sites appears to depend on the motivation and ability of the student assigned. This data would suggest that perhaps some students are more motivated to document their interventions and may be more proficient at identifying them when they occur.

Students made several different interventions during the 4-year study period, but doing chart reviews, fixing dosing issues, and ensuring appropriate therapy were consistently the most common interventions made. Whether the students felt more comfortable making these types of interventions, were more proficient at identifying them, or were just more often exposed to them is unknown. The highest dollar interventions were also the same in each year: prevention of allergic reactions, prevention of drug interactions, and identification of contraindications. Students documented these interventions much less compared to other types of interventions. Prevention of an allergic reaction made up only 400 of the 59,613 interventions made (0.7%). Drug interactions accounted for 1041 (1.7%) interventions, and contraindications accounted for 876 (1.5%). This could be cause for concern as these are all essential interventions that pharmacists are relied upon to make on a routine basis and students would be expected to identify as well. Students may not be proficient yet at identifying these types of interventions when they occur; alternatively, there may have been fewer of these interventions to make compared to other interventions. However, a comparison of these specific student intervention percentages to pharmacist intervention percentages indicates that these types of interventions are not among the most common interventions made. A study published in 2007 of pharmacist interventions in the emergency department reported that 40 (1.9%) of 2150 total interventions made were allergy notifications and only 2 (0.1%) were drug interaction interventions.22 The American College of Clinical Pharmacy Practice-Based Research Network Medication Error Detection, Amelioration and Prevention Study indicated that clinical pharmacists made 42 interventions in which a contraindicated drug was prescribed, which represented approximately 4% of the 1007 total interventions documented.23 These findings suggest that interventions involving identification of an allergy, possible drug interaction, or contraindication are indeed less common than other types of pharmacist interventions.

CONCLUSION

Doctor of pharmacy students routinely make clinical interventions during APPEs that are economically beneficial. Using a commercially available documentation program can help quantify these interventions. Addressing dosing issues, ensuring appropriate therapy, and conducting chart reviews are the most common types of interventions made by pharmacy students during APPEs, while preventing allergic reactions to drugs, and identifying drug interactions and contraindications generate the most cost savings per intervention. In addition, the financial benefits of precepting students can vary greatly depending on the students assigned to the APPE site.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author acknowledges the efforts of Brooke A. Linn, Assistant Director of Student Services, for her work in editing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Skrabel M, Jones R, Nemire R, et al. National survey of volunteer pharmacy preceptors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205112. Article 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plaza C, Draugalis R. Implications of advanced pharmacy practice experience placements: a 5 year update. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3) Article 45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed July 12, 2013.

- 4.Knapp K, Manolakis M, Webster A, Olsen KM. Projected growth in pharmacy education and research, 2010 to 2015. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6) doi: 10.5688/ajpe756108. Article 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor C, Church C, Byrd D. Documentation of clinical interventions by pharmacy faculty, residents, and students. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(7-8):843–847. doi: 10.1345/aph.19310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briceland L, Kane M, Hamilton R. Evaluation of patient-care interventions by PharmD clerkship students. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49(5):1130–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brockmiller H, Abel S, Koh-Knox C, et al. Cost impact of PharmD candidates’ drug therapy recommendations. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56(9):882–884. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.9.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller B, Abel S. Impact of college of pharmacy-based educational services within the hospital. DICP. 1990;24(4):422–425. doi: 10.1177/106002809002400416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Condren M, Haase M, Luedtke S, et al. Clinical activities of an academic pediatric pharmacy team. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(4):574–578. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennehy CE, Kroon LA, Byrne M, Koda-Kimble MA. Increase in number and diversity of clinical interventions by PharmD students over a clerkship rotation. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62(Winter):373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell AR, Nelson LA, Elliott E, Hieber R, Sommi RW. Analysis of cost avoidance from pharmacy students’ clinical interventions at a psychiatric hospital. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7518. Article 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino J, Caballero J, Llosent M, Hinkes R. Differences in pharmacy interventions at a psychiatric hospital: comparison of staff pharmacists, pharmacy faculty, and student pharmacists. Hosp Pharm. 2010;45(4):314–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shara M, Garis R, Moore F. Positive economic impact of pharmacy clerkship students in an intensive care unit. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65 Article 84S. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiVall MV, Zikaras B, Copeland D, Gonyeau M. School-wide clinical intervention system to document pharmacy students’ impact on patient care. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(1) doi: 10.5688/aj740114. Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson TL, Fox BI, Andrus M, Carroll D. Implementation of a school-wide clinical intervention documentation system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe75590. Article 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolley AB, Berds CA, Edwards RA, Copeland D, DiVall MV. Potential cost avoidance of pharmacy students’ patient care activities during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778164. Article 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mersfelder T, Bouthillier M. Value of the student pharmacist to experiential practice site: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(4):541–548. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Web-based pharmacy intervention documentation and reporting. Clinical Measures Web site. http://www.goldstandard.com/product/pricing-analysis-cost-control/clinical-measures/. Accessed May 17, 2013.

- 19.ProspectoRx Web site. https://prospectorx.com. Accessed May 17, 2013.

- 20.Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Occupational employment and wages, May 2012. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291051.htm. Accessed July 11, 2013.

- 21.Davis SM, Rudd CC. Cost of training doctor of pharmacy students in a clinical practice setting. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(10):2288–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lada P, Delgado G., Jr. Documentation of pharmacists’ interventions in an emergency department and associated cost avoidance. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64(1):63–68. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo GM, Touchette DR, Marinac JS. Drug errors and related interventions reported by United States clinical pharmacists: the American College of Clinical Pharmacy practice based research network medication error detection, amelioration, and prevention study. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(3):253–265. doi: 10.1002/phar.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]