Abstract

Objectives. To determine the academic pharmacy community’s perceptions of and recommendations for tenure and tenure reform.

Methods. A survey instrument was administered via either a live interview or an online survey instrument to selected members of the US academic pharmacy community.

Results. The majority of respondents felt that tenure in academic pharmacy was doing what it was intended to do, which is to provide academic freedom and allow for innovation (59.6%). Respondents raised concern over the need for faculty mentoring before and after achieving tenure, whether tenure adequately recognized service, and that tenure was not the best standard for recognition and achievement. The majority (63%) agreed that tenure reform was needed in academic pharmacy, with the most prevalent recommendation being to implement post-tenure reviews. Some disparities in opinions of tenure reform were seen in the subgroup analyses of clinical science vs basic science faculty members, public vs private institutions, and administrators vs nonadministrators.

Conclusions. The majority of respondents want to see tenure reformed in academic pharmacy.

Keywords: academic freedom, academic tenure, tenure, faculty

INTRODUCTION

Academic tenure, including its implementation and interpretation, is a highly debated and controversial topic within the academy and society. The reform of tenure is an extremely contested topic in higher education, and in recent years, it has received increased attention from boards of higher education, state legislatures, faculty members, university administrators, and other public officials. While the origins of tenure included the protection of academic freedom, the system has come under intense scrutiny and its necessity is challenged by today’s society.1-6

The American Association of University Professors, founded in 1915, in conjunction with other organizations, has set forth standards and practices for academic freedom and tenure. The definitions and statements developed in 1915 and further modified in 1940 are still the guiding principles used today for defining academic freedom and tenure. Though the principles of academic freedom and tenure have remained similar to those originally conceptualized, changes in the system are occurring. Across colleges and universities in the United States, the percentage of degree-granting institutions with tenure systems has declined. In 1993-1994, 63% of all degree-granting institutions had a tenure system compared to 48% in 2009-2010.7 In the same timeframe, the percentage of full-time instructional staff members with tenure declined from 56% to 49%.

In academic pharmacy, a similar trend with tenure has been observed. A decline in the percent of full-time tenured and tenure-track, nontenured faculty members has occurred over the past 20 years.8 In 1990, 45% of full-time faculty members, in all academic ranks, were tenured compared to 31% in 2011-2012, with the most change from 42% to 31% occurring in the past 12 years. The percent of tenure-track, nontenured faculty members also declined from 26% to 21% for the same time period, and there has been a shift away from tenure as shown by a change in nontenure-track faculty members increasing from 28% to 37%. There likely has been a decline in tenured faculty members due to institutions not offering a tenure-track option, such as for some clinical faculty members, or even having tenure at its institution. In 2010-2011, the data were first reported by AACP and showed that 10% of full-time faculty members in academic pharmacy were in nontenure-track institutions.

With the flux in tenured positions, the debate about tenure continues, with strong opinions from both advocates and critics of the system. Supporters of tenure consider it essential to protecting academic freedom and preserving research, which is viewed as necessary to advance knowledge and ultimately benefit society.3,9 To protect individuals in their employment, tenure creates a system of due process to ensure that a professor’s dismissal is for cause and is not because of their views or research findings.10 Those that challenge tenure believe this protection makes it difficult to terminate incompetent faculty members and promotes complacency.3 Those against tenure also believe that it impedes creativity and freedom in faculty members trying to achieve tenure because the rigid time clock and focused goals set for them to achieve tenure does not allow them the opportunity to truly explore and research.3

Advocates of tenure state that it provides faculty members with freedom of speech, especially on controversial topics, and provides a mechanism for faculty members to influence decision-making and governance within universities.4 Critics believe tenure actually hinders the freedom of speech of nontenured faculty members because of the way in which most universities make tenure decisions, ie, tenured faculty members are allowed to hold the decision to grant tenure for other faculty members. By some points of view, this inability to speak openly about ideas is bullying and pervasive at universities.11,12

Until the Age Discrimination in Employment Act was passed in 1967 and the amendments of 1978 and 1986, the lifespan of a tenured faculty member was approximately 30 years.12 Prior to this Act, faculty members generally retired at age 65; after the Act was passed, the age limit for retirement disappeared. Consequently, when faculty members receive tenure, they may believe they have a job for life, and some argue that this results in a decline in productivity. The open-ended contract of employment or job security is seen as a benefit of tenure, but it is believed by others to be financially straining to the institution, especially during tough economic times.2 Because of the employment obligations to tenured faculty members, who are generally the highest paid faculty members, this leaves less funding to hire new faculty members or to respond quickly to changes in the marketplace.3,4,12

Although the tenure debate is commonly occurring in higher education, limited information was found in the literature about the tenure debate or potential reform needed to the tenure system in academic pharmacy. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine: (1) the perceptions among the academic pharmacy community on tenure; (2) the perceptions of the academic pharmacy community regarding the need for tenure reform; and (3) the nature of tenure reform recommendations by the academic pharmacy community.

METHODS

A survey instrument was developed by the investigators based on a review of the literature that discussed the debate regarding the tenure system in pharmacy education and higher education in general. The survey instrument was pretested by 1 faculty member at each investigator’s home institution, and then revised based on feedback. Each investigator submitted and received approval for the research protocol from their home institution’s institutional review board. (A copy of the survey instrument can be obtained from the corresponding author.)

The survey collected demographic data as well as 3 domains of information: perception of the tenure system at the participant’s home institution, if their institution had a tenure system; perceptions of the tenure system in general; and perceptions regarding the future of tenure in academic pharmacy. The participants had the following options for answering the 34 survey questions: strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, do not know, not applicable. The participant also had the ability to skip a question if they did not wish to answer it.

Participants were included in the study if they were currently employed as a president, provost, administrator, or faculty member at a US university or college with a school of pharmacy. Participants were included from each investigator’s home institution or were in the AACP Academic Leadership Fellows Program (ALFP), cohorts through 2011. Subjects were excluded if they were retired or no longer employed at a university or college with a school of pharmacy. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and participants did not receive compensation for participating.

The survey was administered by 2 methods, either through a live interview or via an online survey instrument. For the live interviews, each investigator requested interviews from a defined population at the investigators’ home institution with the following faculty members and administrators: president, provost, dean, and a combination of 14 tenure or contract faculty members and nontenure track pharmacy faculty members (n=101). The online survey instrument was administered to a cohort sample of fellows from ALFP (n=202).

For the live interviews, once the faculty member or administrator agreed to participate in the study by responding to the standard recruitment letter, written informed consent was obtained prior to administration of the survey. The survey instrument was provided to those who agreed to participate at least 3 days prior to the live 30-minute interview conducted by the investigator.

The online survey was administered via the online survey tool, SurveyMonkey, to the ALFP cohort. The recruited study participants received an e-mail that contained the link to the online survey instrument. The first page of the survey instrument was the informed consent form, which the participant was required to complete before they could proceed. Participation was anonymous.

The live survey data were submitted online by each investigator through a SurveyMonkey link. The electronic results from the 2 arms of the survey were aggregated and analyzed as one survey. Data were de-identified and exported into IBM SPSS for Mac, version 21 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). As the data were non-normally distributed and were nominal in nature, nonparametric tests (chi-square, Mann Whitney U test, and Kruskall-Wallis) were used to test for association between responses. Subanalyses were performed based upon respondent’s type of institution (private vs public), departmental home (basic vs clinical science), and administrative role (administrator vs non-administrator). A clinical science departmental home was defined as pharmacy practice combined with social and administrative sciences. An administrator was defined as a department chair, assistant/associate/executive/vice dean, dean, provost, chancellor or president. An a priori level of less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was set as significant and differences meeting this criterion were reported. Missing data were not estimated or used in analyses. The free response questions were tabulated and analyzed using thematic analysis for commonly occurring themes.13

RESULTS

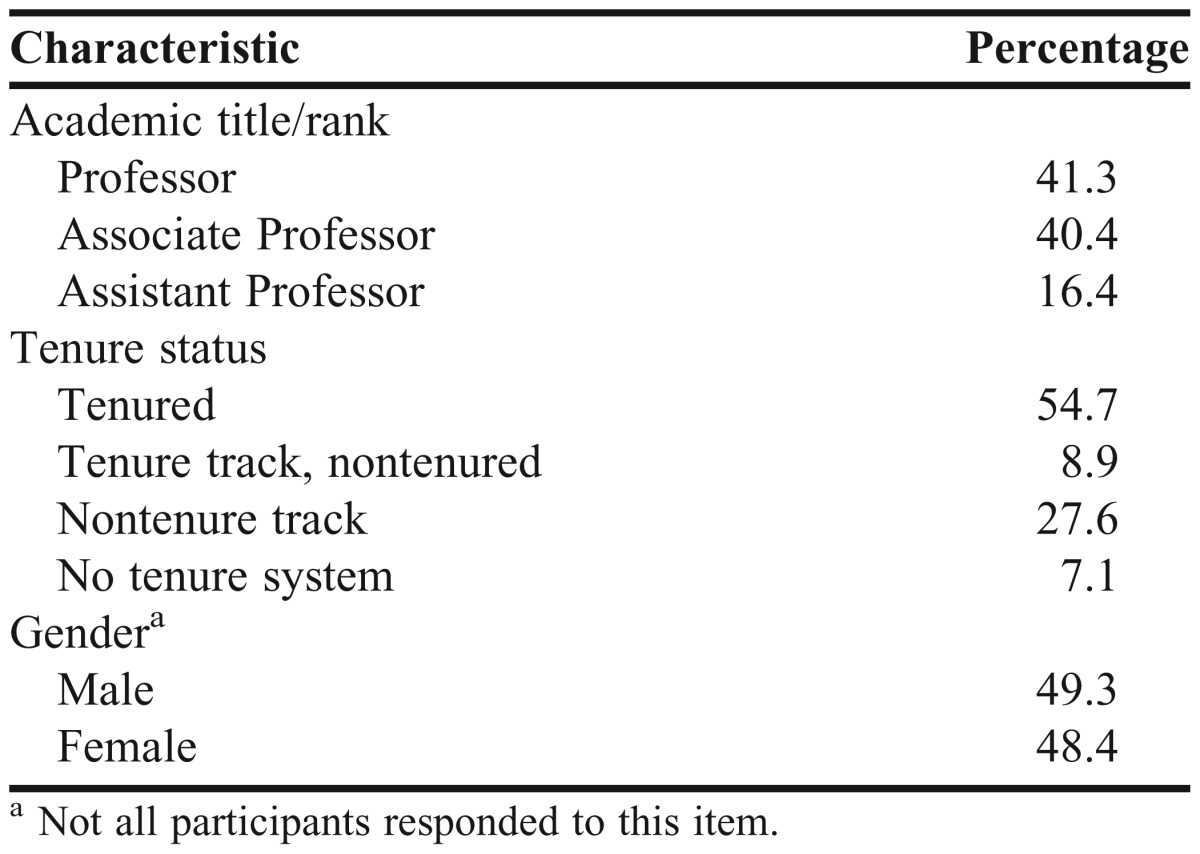

Two hundred twenty-five participants completed the survey: 80 completed a live interview and 145 completed the online survey instrument. For the online survey, the number of responses was met to be a representative sample according to Krejcie and Morgan.14 The demographic profile for the participants’ faculty rank, tenure status, and gender are given in Table 1. Most respondents had between 2 and 15 years of experience at their current institution; however, most respondents had between 11 and 30 years of experience in the higher education industry. Fifty-two percent of the respondents had worked outside of higher education, with the most common areas being hospital pharmacy, community pharmacy, and industry. The largest percentage of respondents (74.2%) worked in pharmacy programs that had existed for 30 years or more. A subgroup analysis was performed between clinical science (71.1%) vs basic science faculty (26.2%); public institutions (56.9%) vs private institutions (40.4%); and administrators (60.4%) vs non-administrators (36.9%).

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Participants in a Survey Examining Perceptions of Tenure and Tenure Reform in Academic Pharmacy, N=225

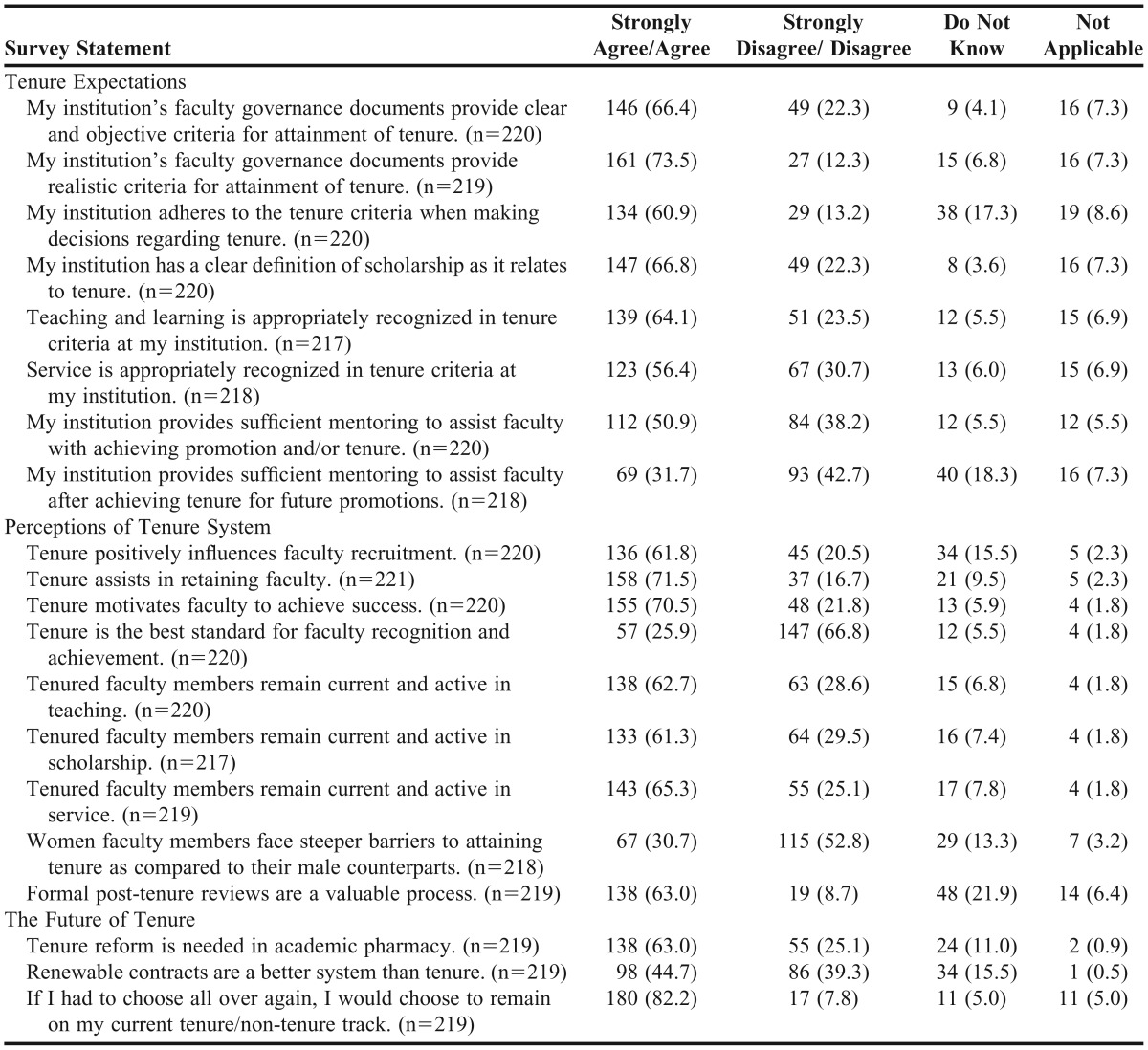

The majority of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with most of the statements regarding tenure expectations (Table 2). There were 2 areas in which agreement was not as strong: recognition of service and mentoring. Just over 55% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that service was appropriately recognized in tenure criteria. When asked if their institution provided sufficient mentoring to assist faculty members with achieving promotion and/or tenure, 50.9% strongly agreed or agreed that there was sufficient mentoring. When asked if their institution provided sufficient mentoring to assist faculty members after achieving tenure for future promotions, 31.7% strongly agreed or agreed that there was sufficient mentoring.

Table 2.

Reponses of Pharmacy Administrators and Faculty Members Regarding Their Expectations and Perceptions of Tenure

For the next section of the survey instrument, the majority of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with most statements regarding perceptions of tenure systems (Table 2). However, when asked if tenure was the best standard for faculty recognition and achievement, only 25.9% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed. Another area in which mixed perceptions were identified was with women achieving tenure. Approximately 31% strongly agreed or agreed that women face steeper barriers in attaining tenure than do their male counterparts.

Sixty-three percent of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that tenure reform was needed in academic pharmacy. When asked if renewable contracts (eg, 5-year contracts) were a better system than tenure, 44.7% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that they were. However, 82.2%, reported that if they had to start over again, they would choose to remain on their current tenure/nontenure track. Respondents were questioned about the original intent of tenure and if it provided academic freedom and allowed for innovation, and approximately 60% responded that it did.

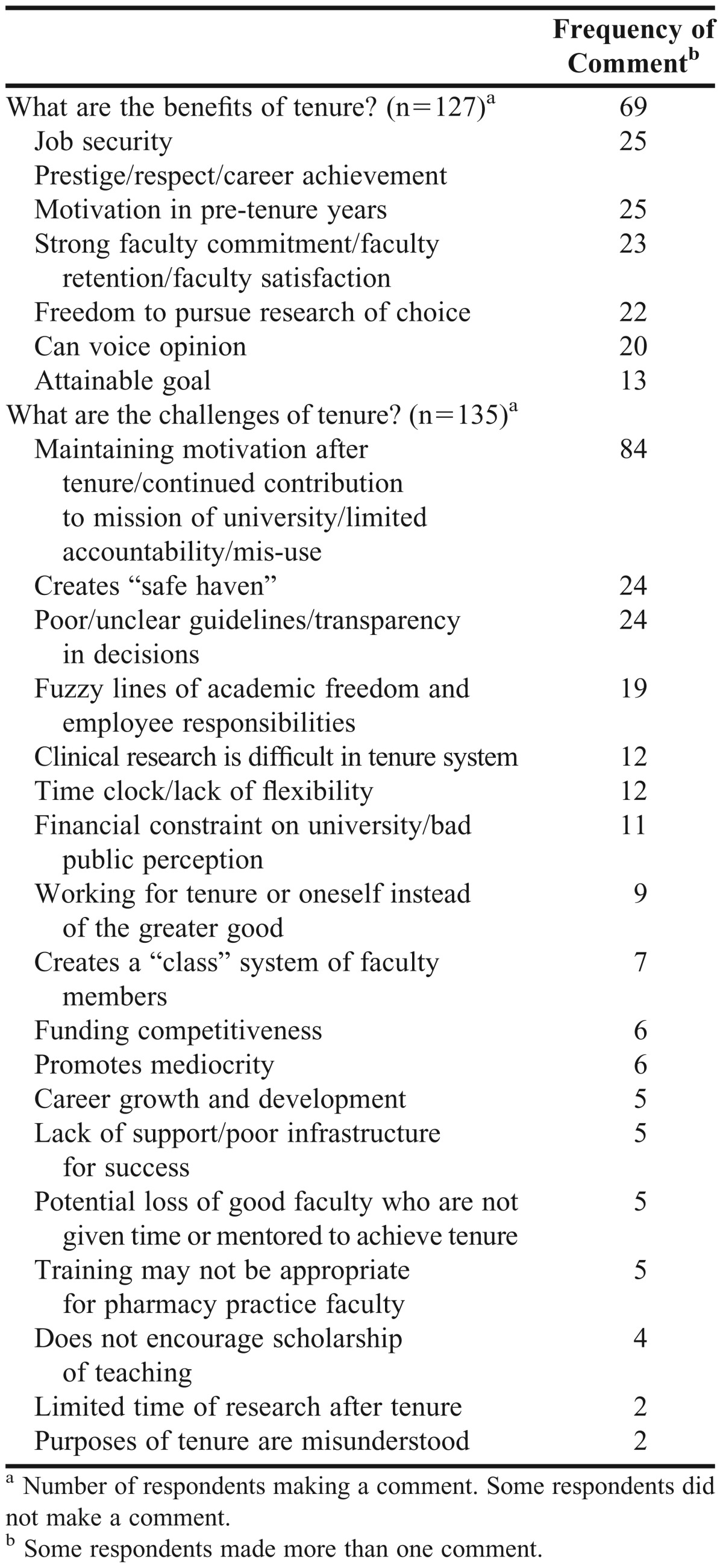

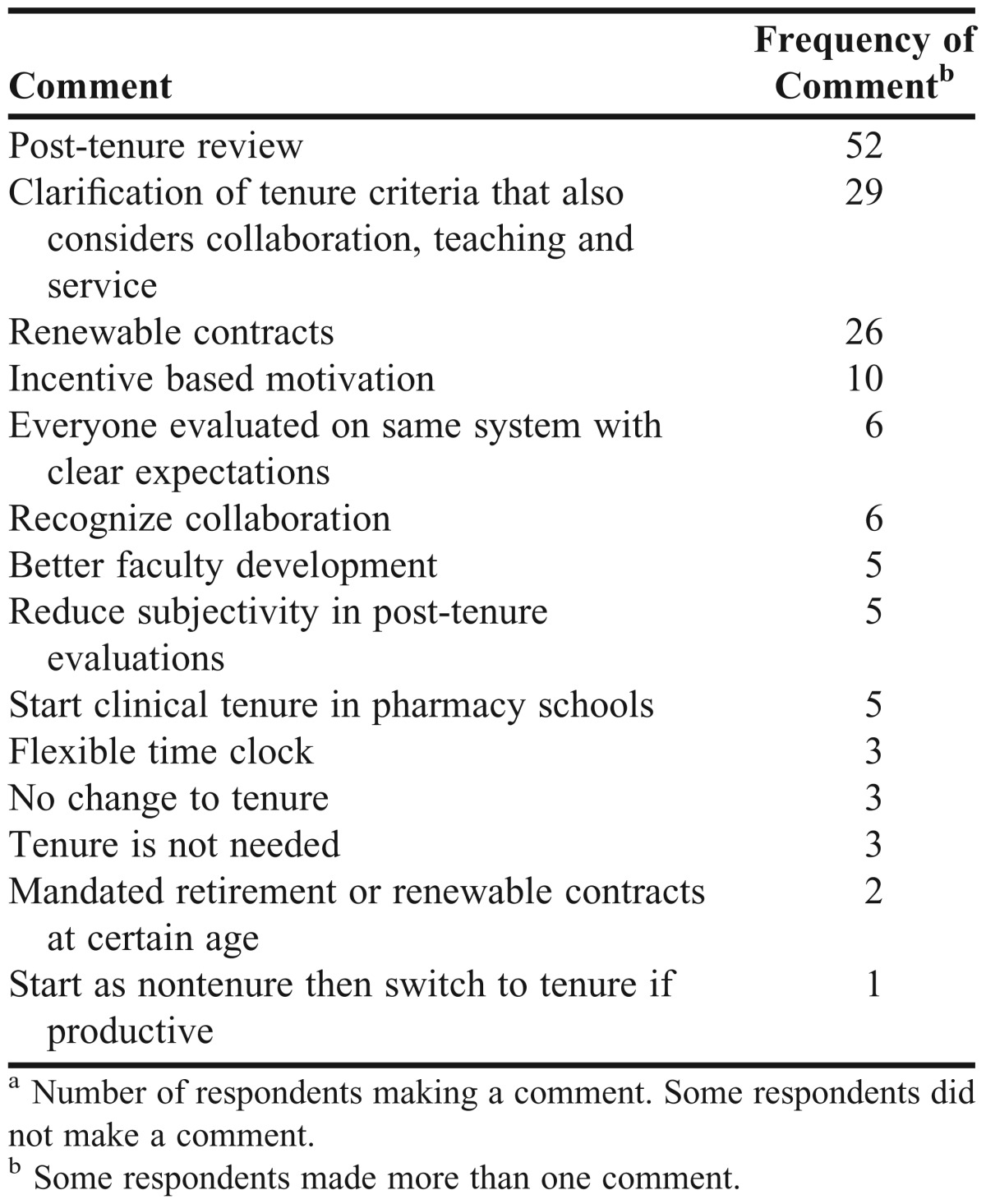

Participants also completed several open-ended questions (Table 3). When asked the benefits and challenges of tenure, the most prevalent benefit cited was job security, and the most prevalent challenge cited was maintaining motivation/contributions and accountability. If the respondent believed that tenure reform was needed, changes and possible alternatives were solicited. The most common recommendation for reform was to have post-tenure review followed by clarification of tenure criteria and renewable contracts. A summary of all responses can be found in Table 4.

Table 3.

Categorization of Participants Responses Regarding the Benefits and Challenges of Tenure in Academic Pharmacy

Table 4.

Categorization of Participants’ Responses Regarding Changes Needed and Alternatives to Tenure in Academic Pharmacy (n=100)a

Subgroup Analyses

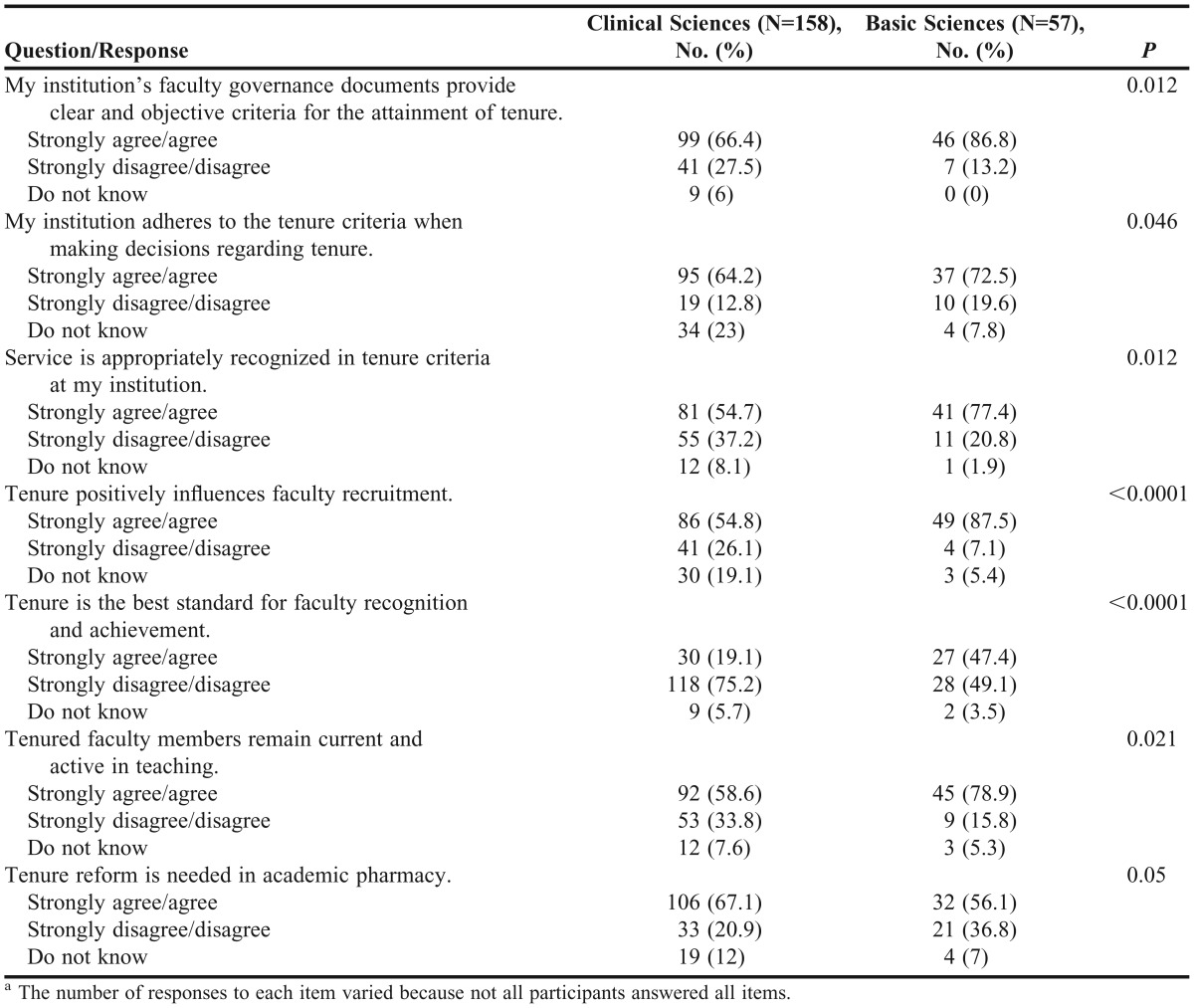

For the subgroup analysis of clinical science vs basic science faculty members, we found that responses to 7 questions were significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 5). A higher percentage of basic science faculty members than clinical science faculty members strongly agreed or agreed that the faculty governance documents were clear and objective, that the institution adhered to tenure criteria for making decisions, and that service was appropriately recognized in tenure criteria. Basic science faculty members also more strongly agreed or agreed than clinical science faculty members that tenure positively influenced faculty recruitment, that tenured faculty members remained current and active in teaching, and that tenure was the best standard for faculty recognition and achievement. Lastly, fewer basic science faculty members than clinical science faculty members believed that tenure reform was needed in academic pharmacy.

Table 5.

Significantly Different Responses to Survey Items by Clinical Science and Basic Science Pharmacy Faculty Members (N=215)a

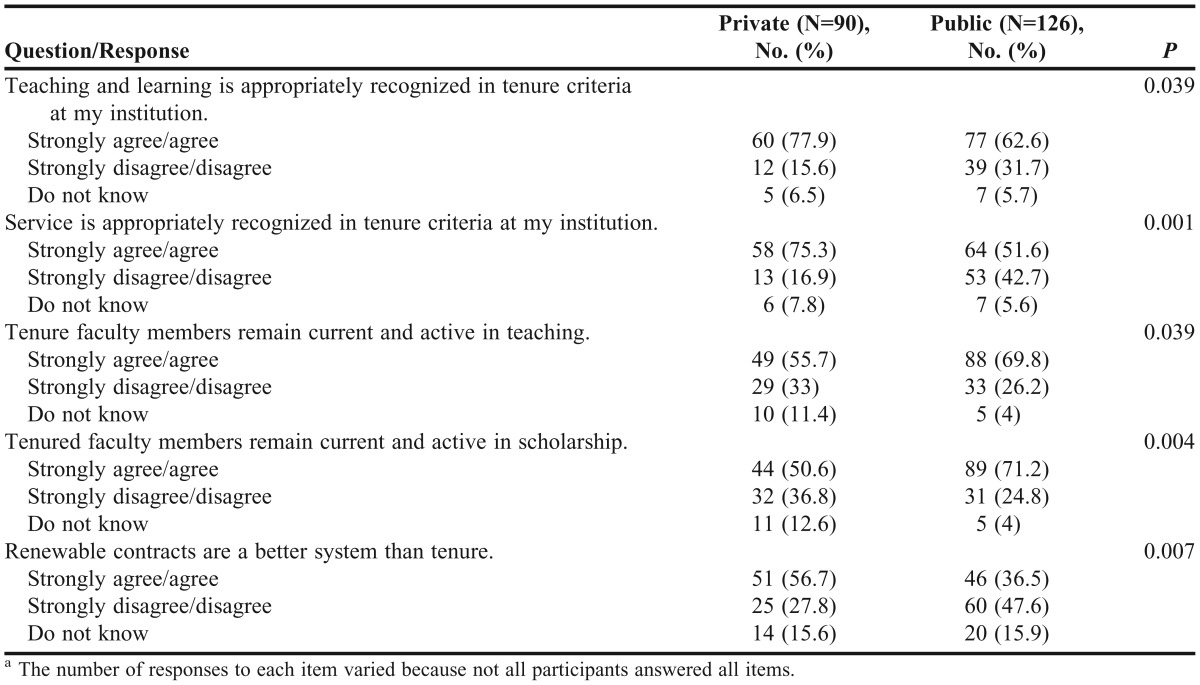

Responses to 5 questions were significantly different between participants representing public institutions vs those representing private institutions (Table 6). A higher percentage of respondents from private institutions than from public institutions strongly agreed or agreed that teaching and learning, and service were appropriately recognized. More respondents in public institutions than in private institutions strongly agreed or agreed that tenured faculty members remained current and active in teaching and active in scholarship. More of the private institution respondents than public respondents strongly agreed or agreed that renewable contracts were better; however, almost 16% for both groups responded that they did not know.

Table 6.

Significantly Different Responses to Survey Items Pharmacy Faculty Members From Private and Public Institutions (N=216)a

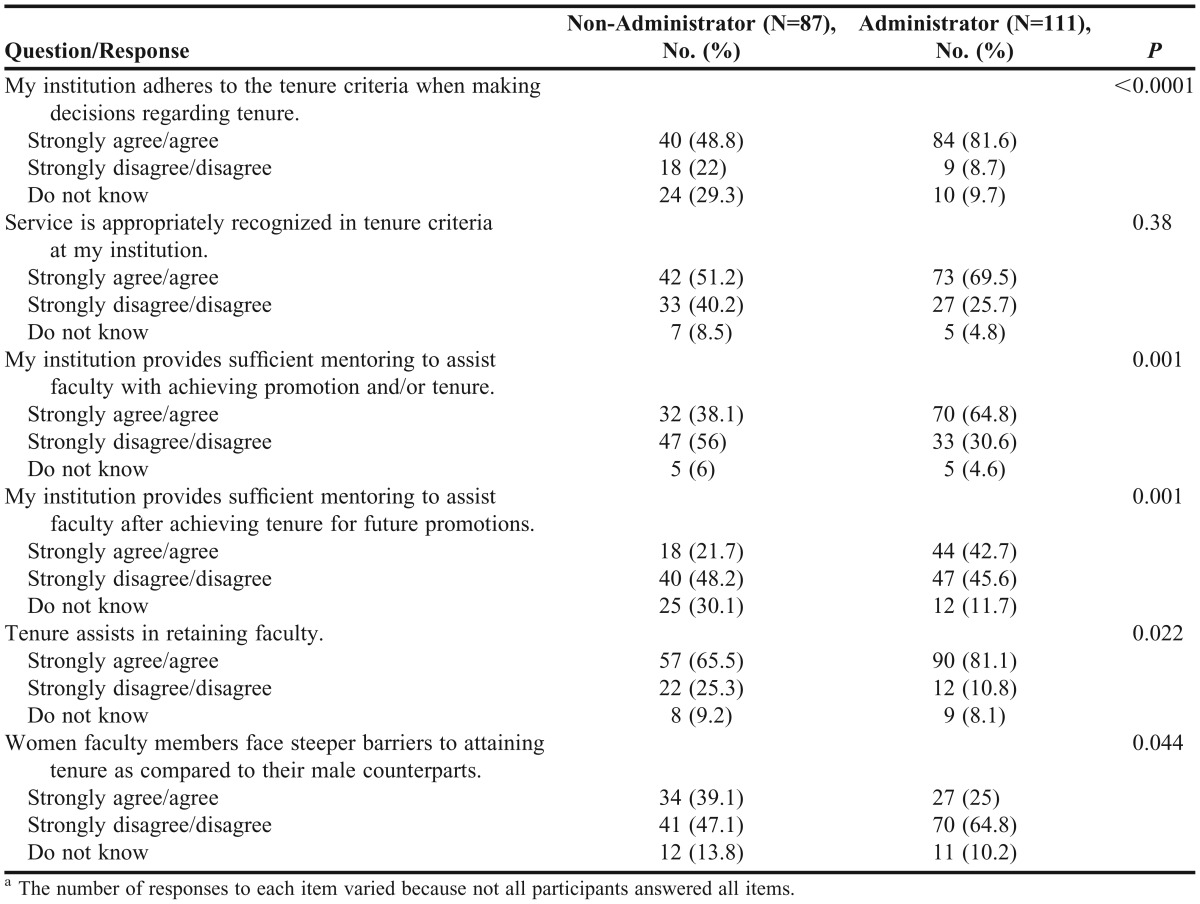

When responses of administrators and non-administrators were analyzed, significant differences were found in responses to 6 questions (Table 7). A higher percentage of administrators than non-administrators strongly agreed or agreed that their institution adhered to tenure criteria when making decisions and that service was appropriately recognized. Approximately 65% of administrators strongly agreed or agreed that sufficient mentoring was provided before achieving tenure compared to 38.1% of non-administrators. As for mentoring after achieving tenure, 42.7% of administrators strongly agreed or agreed that it was sufficient compared to 21.7% of non-administrators. More administrators believed that tenure assists in retaining faculty members compared to non-administrators. Approximately 40% of non-administrators agreed or strongly agreed that women faculty members face steeper barriers to attaining tenure than men; 25% of administrators agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.

Table 7.

Significantly Different Responses to Survey Items by Nonadministrators and Administrators in Academic Pharmacy (N=198)a

DISCUSSION

Tenure reform is a highly debated topic; however, limited information is published in the pharmacy literature. This study found that faculty members’ perceptions of tenure were generally positive in the overall sample, except for the areas of service and mentoring before and after achieving tenure. Interestingly, while the majority of respondents did not agree that tenure was the best standard for recognition and achievement, a large majority indicated they would choose the same track if they had to do it over again. The majority of faculty members and administrators felt that tenure was doing what it was intended to do, which is to provide academic freedom and allow for innovation, but the majority also wanted tenure to be reformed in academic pharmacy. Even though most colleges and universities have not undergone tenure reform, the most prevalent recommendations for tenure reform were post-tenure review, clarification of tenure criteria, and renewable contracts.

The overall perceptions of tenure in this study were fairly positive, but an interesting finding was faculty members’ perception of mentoring at institutions. Only 50% of participants agreed there was sufficient mentoring with regard to achieving promotion and/or tenure and less agreed that there was sufficient mentoring after achieving tenure for future promotions. Administrators and non-administrators differed in their views of mentoring, where almost 65% of the administrators agreed with sufficient mentoring for achieving promotion and/or tenure compared to 38.1% of non-administrators. The results are difficult to interpret between the 2 groups related to mentoring after achieving tenure as approximately 43% of administrators agreed it was sufficient compared to approximately 22% of non-administrators, but 30% of non-administrators reported they did not know, likely because they have not yet achieved tenure. The need for faculty development programs, including mentoring, has been documented in pharmacy literature. Programs have been more focused on tenure track faculty members than non-tenure track faculty members.15 However, guidelines for a mentoring program specific for pharmacy practice faculty members has been published.16 Perhaps with more focus on this issue, more mentoring programs will be implemented to address this concern.

Inequities between nontenure-track and tenure-track faculty members in terms of start-up packages, voting rights, and job responsibilities have been described.17-19 Nontenure-track faculty members are often defined as clinical or pharmacy practice faculty members. For this study, the authors’ subgroup analysis was between clinical science faculty members, which included pharmacy practice (83%) and social and administrative sciences (17%) vs basic science faculty members. Even with the majority of the clinical science faculty members being tenured/tenure-track (57%), issues with tenure were still voiced in this study by this subgroup. Their perceptions around recognizing service, applying tenure criteria, tenure criteria clarity, and tenure’s impact on recruitment were not as positive as those of basic science faculty members. In addition, 67% of the clinical science faculty members agreed that tenure reform was needed in academic pharmacy compared to basic science faculty members at 56%. Interestingly, less than 20% of clinical science faculty members agreed tenure was the best standard for recognition and achievement compared to 47% of basic science faculty members. Though the reasons for these opinions related for this study are not known, the authors, anecdotally, have heard concerns over the differences in job responsibilities, especially related to responsibilities of clinical education for clinical faculty members. With the concerns raised and the number of respondents who want tenure criteria clarified, presumably to clarify job responsibilities, this issue merits further investigation.

Disparities in tenure rates between male and female faculty members were reported in previous studies,20 but we found mixed opinions among the participants in this study. Almost 46% responded that they did not agree that women faced steeper barriers in attaining tenure as compared to their male counterparts, although 13% reported that they did not know. There was a significant difference in the perceptions of administrators and non-administrators on this issue. Approximately 40% of non-administrators agreed that women face steeper barriers than men, compared to 25% of administrators. The rationale for this perception is unknown.

Even though respondents’ overall perceptions of tenure were generally positive, the majority wanted to see tenure reformed. While there were many recommendations for reform solicited, 3 types of reform were cited most often. The most prevalent recommendation for tenure reform was post-tenure review. However, approximately 40% of the respondents already had a formal or informal post-tenure review in place at their institution. Post-tenure review has previously been supported in the pharmacy literature and has been seen as an opportunity to show critics of tenure that professorial standards are protected through a system of peer review.21

The second most prevalent recommendation for tenure reform was clarification of tenure criteria. Further information is needed to determine exactly what needs to be clarified as the majority of study participants agreed that tenure criteria were clear, objective, and realistic, and that tenure criteria were applied when making tenure decisions. The majority also agreed that scholarship had a clear definition, teaching and learning were appropriately recognized, and to a lesser extent, that service was appropriately recognized. Two themes did stand out in the subgroup analyses that may suggest areas for clarifying tenure criteria: recognizing service and applying tenure criteria when making tenure decisions. Issues with recognizing service in tenure criteria consistently showed in each of the subgroup analyses where clinical science faculty members, public institutions and non-administrators did not agree as strongly that service was appropriately recognized as compared to basic science faculty members, private institutions, or administrators. In 2 of the subgroup analyses, the clinical science faculty members and non-administrators did not agree as strongly that their institution adhered to tenure criteria when making decisions regarding tenure compared to basic science faculty members and administrators. The clinical science faculty members also did not agree as strongly as did basic science faculty members that criteria for tenure were clear and objective. While the authors do not believe that tenure should be a checkbox system, as some faculty members may wish it to be, there may need to be some clarity in tenure criteria for different disciplines.

The third most prevalent recommendation for tenure reform was to use renewable contracts, and 45% of the respondents agreed this was a better system than tenure. In the subgroup analysis between private and public institutions, a higher percentage of respondents from private institutions than public (57% vs 37%) believe that renewable contracts were a better system than tenure. The number of faculty members supporting renewable contracts may increase as more colleges and schools move away from the tenure system.

Possible limitations to this study include the population sampled. Though the authors tried to gain a broad base perspective of faculty members and administrators, the distribution of tenured faculty members does not exactly match the AACP demographic profile on the distribution of tenured faculty members in the academy. This study had a higher percentage of tenured faculty respondents than reported in the academy. This was likely the result of the ALFP cohort sample which tended to be more experienced and included more tenured faculty members. There was also a higher percentage of pharmacy practice faculty members in the sample than is in the academy. The manner in which the survey was conducted could be a limitation. The authors conducted personal interviews at their institutions. This was meant to gain additional insights on the topic, but it may have led to author interpretation and bias. Also, there were some statements to which a higher percentage of respondents than anticipated answered “did not know.” As there was no way to determine whether the respondent simply did not know, or if the respondent had not yet experienced the situation and therefore did not know how to respond, the data could not be interpreted.

CONCLUSIONS

Tenure reform is a highly debated topic in higher education, but minimal information has been published about the perceptions of pharmacy faculty members. While the majority of the respondents in this study believed that tenure does what it is intended to do, ie, provide academic freedom and allow for innovation, the majority of respondents want tenure reform. Because this study does not have the solution for how to fix the concerns raised about the current tenure systems, such as with recognizing certain aspects of the jobs, clarity of tenure criteria, how to best mentor before and after achieving tenure, further research and debate need to occur to find a solution that best suits the needs of the academy and profession.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank AACP for their support of research through the ALFP program. The research was presented at the AACP Annual Meeting in San Antonio, July 12, 2011. The results reported in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the institutions that participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson C, Taylor M, Kezar A, Vedder R, Trower C. What if college tenure dies? The New York Times Web site. July 19, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2010/07/19/what-if-college-tenure-dies. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- 2.Shea C. The end of tenure? The New York Times Web site. September 3, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/05/books/review/Shea-t.html. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- 3.Hacker A, Dreifus C. Higher Education? How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids—and What We Can Do About It. New York, New York: Time Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tenure Wilson R. RIP: What the vanishing status means for the future of education. The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. July 4, 2010. http://chronicle.com/article/Tenure-RIP/66114/. Accessed September 15, 2010.

- 5.Clawson D. Tenure and the future of the university. Science. 2009;324(5931):1147–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1172995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley NS, Nelson C. Should tenure for college professors be abolished? The Wall Street Journal Web site. June 24, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303610504577418293114042070. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- 7.US Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics, 1993-1994 through 2009-10 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Fall Staff Survey. September 2010. http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_274.asp. Accessed October 4, 2011.

- 8.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Institutional Research Report Series, Profile of Pharmacy Faculty. 1990-2010 editions.

- 9.Peterson M. J Dent Educ. 3. Vol. 71. Academic tenure and higher education in the United States; 2007. implications for the dental education workforce in the twenty-first century; pp. 354–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stripling J. Most presidents prefer no tenure for majority of faculty. The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. May 15, 2011. http://chronicle.com/article/Most-Presidents-Favor-No/127526/. Accessed May 16, 2011.

- 11.Fendrich L. Time’s up for tenure. The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. April 9, 2008. http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/times-up-for-tenure/5852. Accessed November 11, 2011.

- 12.Trachtenberg SJ. Want tenure? Sign on the dotted line… The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. October 24, 2008. http://chronicle.com/article/Want-Tenure-Sign-on-the/7387. Accessed August 9, 2010.

- 13.Ezzy D. Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation. Australia. Allen and Unwin; 2002. Crows Nest NSW. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30:607–610. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guglielmo BJ, Edwards DJ, Franks AS, et al. A critical appraisal of and recommendation for faculty development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6):Article 122. doi: 10.5688/ajpe756122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metzger AH, Hardy YM, Jarvis C, et al. Essential elements for a pharmacy practice mentoring program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(2):Article 23. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiPiro JT. Nontenure-track faculty and university status. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4):Article 113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glover ML, Deziel-Evans L. Comparison of the responsibilities of tenure versus non-tenure track pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(Winter):388–391. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raehl CL, MacLaughlin EJ, Bond CA. Upgrading nontenure-track pharmacy practice faculty from second- to first-class citizens. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4):Article 115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svarstad BL, Draugalis JR, Meyer SM, Mount JK. The status of women in pharmacy education: persisting gaps and issues. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zito SW. We had it all…academic freedom and tenure. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63(1):Article 107. [Google Scholar]