Abstract

Objective. To evaluate an interprofessional faculty seminar designed to explore the topic of interprofessional education (IPE) as a way to encourage dialogue and identify opportunities for collaboration among health professional programs.

Design. A seminar was developed with the schools of pharmacy, nursing, dental medicine, and medicine. Components included a review of IPE presentation, poster session highlighting existing IPE endeavors, discussion of future opportunities, and thematic round tables on how to achieve IPE competencies.

Assessment. Fifty-four health professions faculty members attended the seminar. Significant differences in knowledge related to the IPE seminar were identified. Responses to a perception survey indicated that seminar goals were achieved.

Conclusion. An interprofessional faculty seminar was well received and achieved its goals. Participants identified opportunities and networked for future collaborations.

Keywords: interprofessional education, seminar

INTRODUCTION

Educating health professions faculty members about the need for interprofessional education (IPE) is a logical step in the strategic planning for IPE.1 Previous literature has highlighted the importance of preparing faculty members for interprofessional teaching, including the use of formal course work.2,3 The objectives of this study were to evaluate an interprofessional faculty seminar designed to explore the topic of IPE, to encourage dialogue for interprofessional collaborations among health professions programs at a Midwestern public university, and to identify opportunities for IPE.

A team of health professions faculty members from the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE) Schools of Dental Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy and the Southern Illinois University (SIU) School of Medicine attended the first Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) Institute in May 2012. One of the strategic planning goals of this faculty team was to develop and implement an interprofessional faculty seminar about IPE during the 2012-2013 academic year.

The seminar was designed to address teaching and learning barriers, which exist at both the individual and organizational levels, as a way to provide faculty members with the knowledge needed to design and implement effective IPE experiences. The design was based on the framework developed by Steinert, which advocates that “if you expect people to work in teams, you best educate them in teams.”4

DESIGN

An IPE seminar steering committee was formed that included the IPEC Institute faculty team as well as 4 other people from the school of medicine (including the associate dean for education and curriculum), and 2 additional people from the school of nursing (including the assistant dean for graduate programs). Based on the experience and knowledge faculty members gained at the IPEC Institute, the steering committee was confident they could plan and implement the seminar despite limited funding. Coming to an agreement on the goals for the seminar was one of the first steps. The committee’s goal was to design a 5- to 6-hour seminar that would achieve the objectives previously delineated. Limited financial resources prevented the steering committee from duplicating the IPEC institute or even inviting a national expert on IPE, however, a full-day of activities and speakers was arranged, pulling heavily from the university’s own faculty resources. The seminar was approved for 4 hours of continuing education credit for pharmacy and nursing.

Determining who should be invited to the seminar was a second point of discussion. The seminar was open to all faculty members of the schools of pharmacy and nursing. The medical school and dental school members of the steering committee identified participants from their respective programs. Faculty members from the schools of nursing and pharmacy in particular were highly encouraged to participate by the steering committee members representing those schools. The school of medicine participants were primarily faculty members who were affiliated with the medical school’s office of education and were coordinators of the various years within the curriculum.

As with planning for IPE learning experiences, another challenge was finding a common time for the event. It was finally determined that the week after spring finals, prior to faculty members with academic contracts being off for the summer, would be good. The seminar was held on the Edwardsville campus. The morning session consisted of pre-assessments, a presentation by the IPEC Institute team on the concepts of IPE, a poster showcase of current IPE endeavors, and presentation of future opportunities for IPE. The afternoon session consisted of thematic round tables with an active-learning exercise for achieving the IPE core competencies, followed by post-assessments.

During the review of IPE, the definition of IPE including what it is and is not, why it is important, models for IPE, an assessment tool to gauge readiness for interprofessional learning (RIPLS) and the core competencies were presented.5,6 The active-learning exercise was conducted to explore the prepositions within the definition of IPE, ie, learning with, from, and about others, were discussed among the teams.7 The question of whether the order of learning matters was also explored. A review of the accreditation standards regarding IPE was presented.8 IPE resources were shared including the MedEdportal from the American Association of Medical Colleges and the Institute of Medicine publication.9,10 Participants could sign-up to join the IPE health team group on the University’s SharePoint account to share resources and continue the dialogue after the seminar.

The poster session consisted of 8 posters highlighting existing IPE endeavors at SIUE/SIU. The range of activities included case-based seminars and simulations, as well as experiential and service learning experiences. Many of the showcased examples were planning further expansion to include more formal credit course work.

The final morning session consisted of the schools of pharmacy, nursing, and medicine sharing IPE opportunities their programs were interested in pursuing. The school of pharmacy presented an error disclosure training IPE opportunity.11-13 The school of nursing presented potential IPE opportunities with various health clinics including the dental clinic at the East St. Louis Education Center. Representatives from the school of medicine presented opportunities for increasing IPE experiential experiences with pharmacy, medical, and nursing students at the Springfield campus.

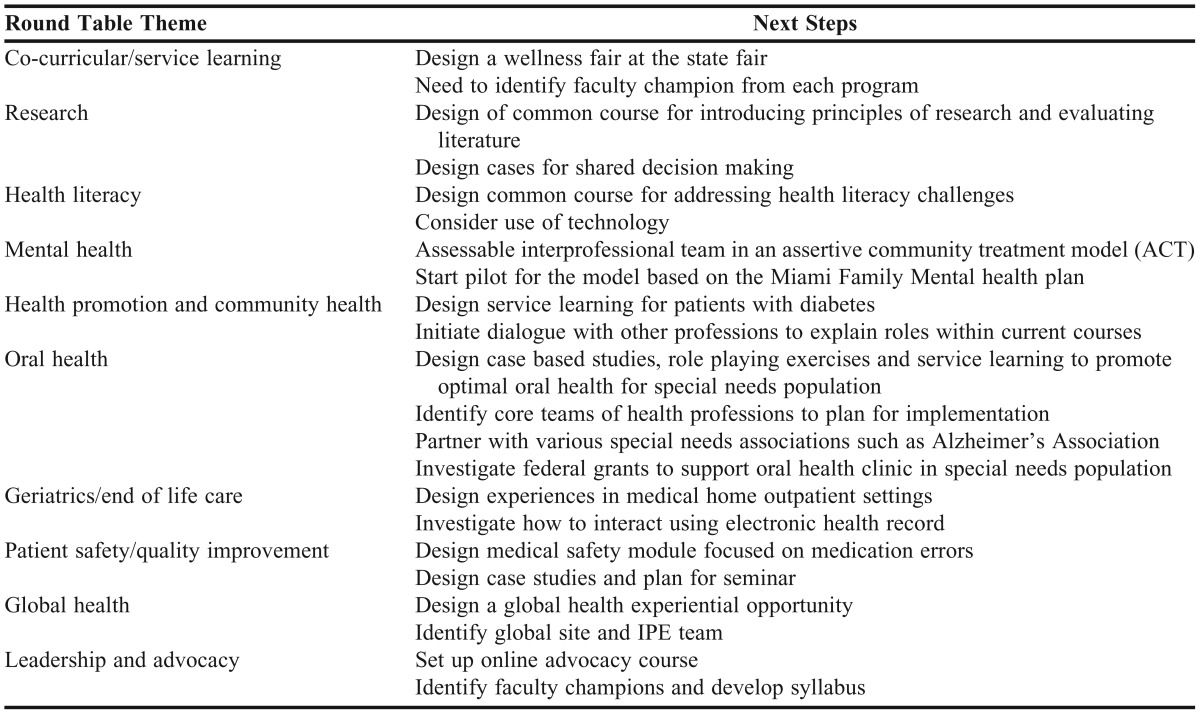

The 2-hour afternoon session consisted of the thematic round tables where interprofessional teams applied principles of cognitive sciences for achieving the core IPE competencies and also applied effective teaching principles to design an IPE learning experience for the chosen theme.14 Ten thematic round tables were assembled (Table 1). Teams were asked to identify the desired outcomes for the experiences and what IPE core competencies are addressed, and to incorporate effective teaching principles. The teams also were asked to indicate what would be the next steps for implementation of this IPE experience. After 1 hour on the exercise, teams reported back to the entire group. To facilitate continued communication after the conclusion of the seminar, a collaborative SharePoint discussion group was created. This group will serve as a reference toolbox for IPE development materials.

Table 1.

Opportunities Identified and Next Steps in Implementation From Thematic Round Tables Conducted as Part of an Interprofessional Education Seminar

Prior to the seminar, all assessment instruments were reviewed and approved as exempt by SIUE’s Institutional Review Board. The pre-seminar assessment consisted of a 10-item knowledge assessment of concepts to be addressed during the seminar. Post-seminar assessments were conducted at the conclusion of the seminar. The post-seminar assessment instrument contained the same knowledge assessment and a 9-item Likert-scale perception survey that included 4 open-ended questions: why IPE is important; what was the most important concept learned about IPE; suggestions for further follow-up; and suggestions to enhance learning from the seminar.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

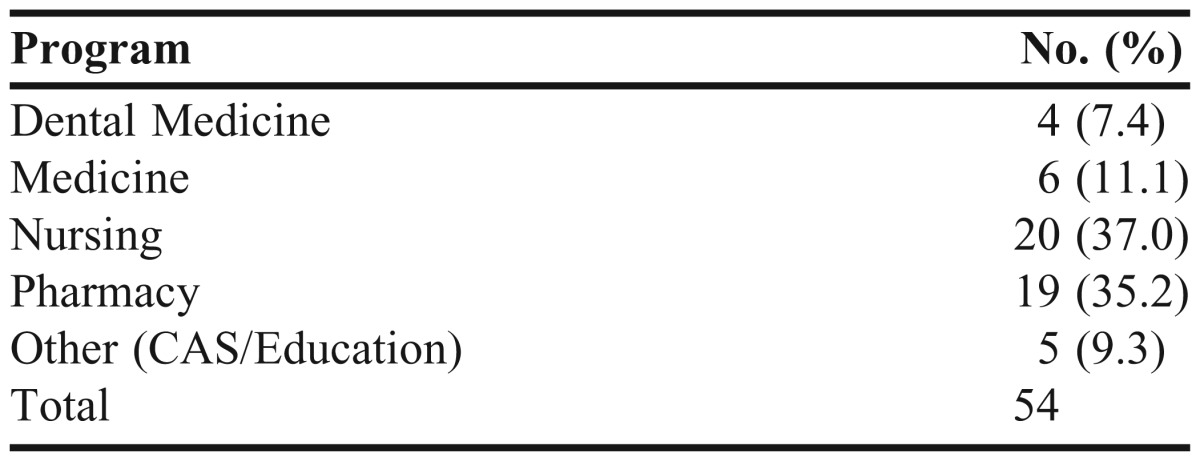

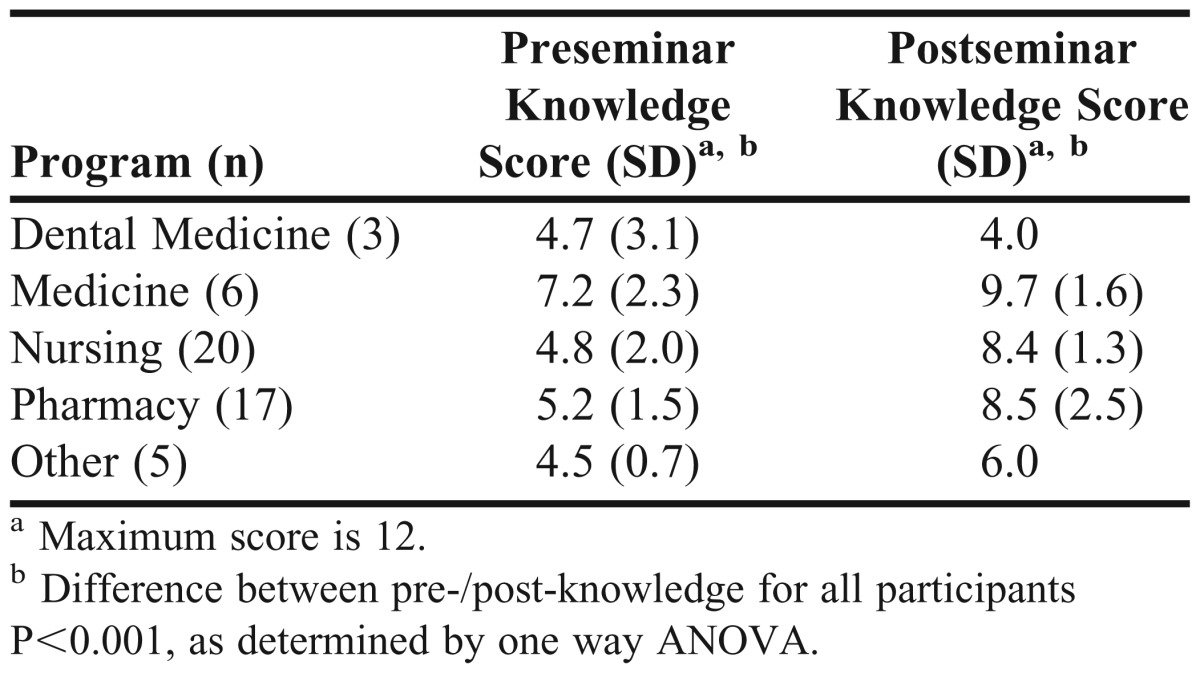

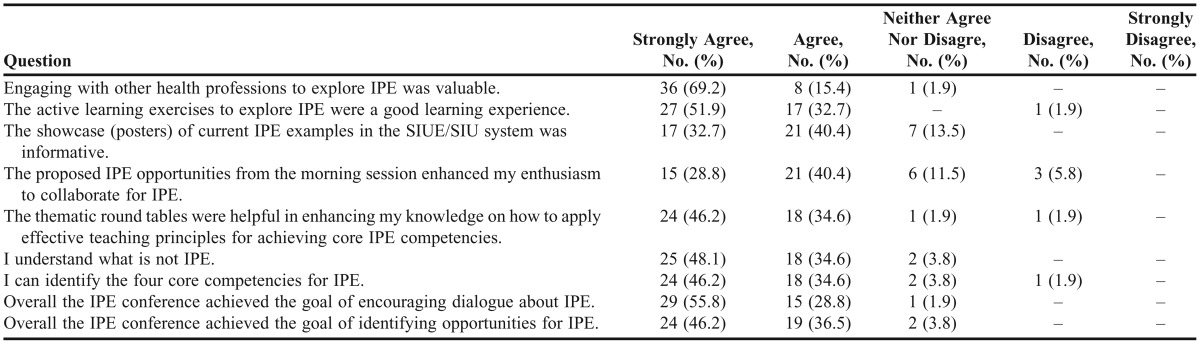

Fifty-four health professional faculty members attended the seminar. The attendees primarily represented the schools of nursing (37%) and pharmacy (35%) (Table 2). The maximum score possible on the 10-item knowledge assessment was 12. There was a significant difference between pre-assessment knowledge (5.1±2.0) and post-assessment knowledge (8.5±2.0) (p<0.001). A comparison of all the collected data by program is presented in Table 3. Perception survey results from the seminar are reported in Table 4. The majority of participants either agreed or strongly agreed that the IPE seminar achieved its goals.

Table 2.

Health Profession of Attendees at an Interprofessional Education Seminar

Table 3.

Comparison by Program of Knowledge Scores of Participants in an Interprofessional Education Seminar

Table 4.

Survey Responses by Participants in an Interprofessional Education Seminar (n=45)

The list of the thematic roundtables and the next steps are summarized in Table 1. Most of the IPE learning experiences generated addressed all 4 core IPE competencies and all addressed at least 3 of the core competencies (roles and responsibilities, communication, and teamwork). The common effective teaching principles applied to the learning experience most often included active involvement and active engagement. Repetition and appeal to visualization were noted.

DISCUSSION

Planning for an IPE seminar that involved key stakeholders from all health professions schools in the university took nearly a year and was challenging. Lessons learned from planning this interprofessional seminar include the importance of obtaining key administrative support from the academic provost and deans of the appropriate programs at the initial planning stages. The steering committee should consist of key administrative persons who will maintain communication within their academic program. Differences of opinions may arise on what will be addressed and how the seminar should be presented. For example, the school of pharmacy wanted to demonstrate error disclosure training by conducting an active role-playing exercise using the University of Washington resources; however, there were concerns about the legal implications of demonstrating this training. Learning to compromise was necessary.

The most valuable component of the seminar as reported from the perception survey was the thematic roundtable discussions. Networking with potential collaborators was an outcome observed. We anticipate that of the many opportunities identified, 2 or 3 of the concepts will result in follow-up action. In particular the error disclosure training resulted in nursing and pharmacy setting plans for further dialogue. The theme of oral health also seemed to have potential for further follow-up and collaboration. Two faculty members from the school of medicine, 1 faculty member from the school of nursing, and 1 faculty from the school of pharmacy planned to follow-up with the interested faculty member in the school of dental medicine.

Faculty members with interest in collaborating on IPE events were more likely to have attended the seminar. The level of participation from the schools of dental medicine and medicine were low. This was attributed to the difference of opinions in these schools regarding whether all faculty members from these schools should have been invited to participate vs only key personnel involved with curriculum decisions.

The most common reasons cited on the perception survey instrument for developing IPE included to enhance patient care and safety, to teach learners to learn together as a means of enhancing their ability to work together later, to prepare students for the real world of health care, and to meet accreditation requirements. The most important concept learned about IPE included the shared interests from other disciplines, numerous IPE opportunities, and the core competencies. Participants were encouraged to continue the dialogue that was begun during the seminar and notify the appropriate person at their school of any initiatives underway as a result of the seminar. Participants expressed interest in having more time for networking and more group time. There were suggestions that more physicians should have been invited to represent the school of medicine. Another suggestion was that having participants rotate among the different round tables could have enhanced learning. Many of the participants commented on the need to move forward after the seminar to implement the ideas discussed.

The design of this seminar adhered to the Steinert model for faculty development for IPE.4 Steinert advocated that it is critical to have faculty development programs in which faculty members from different health professions come together to learn about IPE and teaching methods for IPE. The model should address faculty attitudes and beliefs about IPE and also transmit knowledge about interprofessional learning, practice, and teaching. The planning and delivery of the seminar by faculty members from different health care professions modeled the IPE premise of teamwork. Organizing participants in interprofessional teams centered around common interests addressed a strategy for creating an effective team. The attitudes about IPE were addressed through the team discussions about the prepositions of the definition of IPE and by reviewing the RIPLS survey. Knowledge about IPE teaching, including models, was shared with the participants. Addressing principles of effective education design was accomplished in the active-learning exercise during the thematic roundtables. The exercise was complex enough so that it could not be done alone and illustrated the value of teamwork and collaboration. Showcasing practices of IPE were accomplished by the poster session. The adoption of a dissemination model for implementation was addressed by creating a collaborative SharePoint group.

Silver et al also used work from Steinert to form their model of a conceptual framework for faculty development related to interprofessional education and collaborative practice.15 They suggested that there is little evidence-based literature to guide faculty development in IPE. They advocated for experiential based development, an organization and leadership climate that values IPE, and creating a perceived need for IPE. They reaffirmed the challenge of engaging physicians in IPE. Initiation of team-based education programs linked to improvements in patient outcomes such as quality improvement or patient safety projects are recommended. The models for faculty development for IPE recommend that it should occur in the clinical setting where teams are practicing.2,3 However, initiating dialogue with various health professionals through a joint faculty seminar also has value in initiating potential collaborations.

SUMMARY

An IPE seminar was well received and achieved the goals set out for it. Participants gained knowledge about IPE and also identified opportunities to network regarding future collaborations. The active-learning exercise focused on common themes helped the participants learn core IPE competencies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the IPE steering committee members: Rhonda Comrie, Chris Durbin, Kathy Ketchum, Debra Klamen, Leslie Montgomery, Helen Moose, Kevin Rowland, and Tracey Smith.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poirier TI, Wilhelm M. Interprofessional education: fad or imperative. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;(4):77. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77468. Article 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson ES, Cox D, Thorpe LN. Preparation of educators involved in interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(1):81–94. doi: 10.1080/13561820802565106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howkins E, Bray J, editors. Preparing for Interprofessional Teaching: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Radcliffe; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinert Y. Learning together to teach together: interprofessional education and faculty development. J Interprof Care. 2005;1(suppl):60–75. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning. Med Educ. 1999;33(2):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge L, Wood V. The power of prepositions: learning with, from and about others in the context of interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(6):452–458. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.715605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zorek J, Raehl C. Interprofessional education accreditation standards in the USA: a comparative analysis. J Interprof Care. 2012:e1–8. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.718295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Association of Medical Colleges. MedEd Portal. http://www.mededportal.org. Accessed May 29, 2013.

- 10.Cuff PA. Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education, Board on Global Health. Vol. 2013. Institute of Medicine; Interprofessional education for collaboration: learning how to improve health from interprofessional models across the continuum of education to practice: workshop summary. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13486. Accessed May 29, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etchegaray JM, Gallagher TH, Bell SK, Dunlap B, Thomas EJ. Error disclosure: a new domain for safety culture assessment. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(7):594–599. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.University of Washington Center for Health Science Interprofessional Education. Research and Practice. Home page. http://collaborate.uw.edu. Accessed May 29, 2013.

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. TeamSTEPPS: national implementation. http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov. Accessed May 29, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Friedlander MJ, Andrews L, Armstrong EG, et al. What can medical education learn from the neurobiology of learning? Acad Med. 2011;86(4):415–420. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820dc197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silver IL, Leslie K. Faculty development for continuing interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(3):172–177. doi: 10.1002/chp.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]