Abstract

Objectives. To examine the impact of a panel discussion on transgender health care on first-year (P1) pharmacy students’ knowledge and understanding of transgender experiences in an Introduction to Diversity course.

Design. The panel consisted of both transgender males and females. After panelists shared their healthcare experiences, students asked them questions in a moderated setting. Students completed evaluations on the presentation and learning outcomes. They also wrote a self-reflection paper on the experience.

Assessment. Ninety-one percent of students agreed that they could describe methods for showing respect to a transgender patient and 91.0% evaluated the usefulness of the presentation to be very good or excellent. Qualitative analysis (phenomenological study) was conducted on the self-reflection papers and revealed 7 major themes.

Conclusion. First-year students reported that they found the panel discussion to be eye opening and relevant to their pharmacy career. Our panel may serve as model for other pharmacy schools to implement.

Keywords: health disparities, transgender, pharmacy education, panel discussion, reflection, qualitative analysis

INTRODUCTION

The topic of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health was added to the Healthy People 2020 initiative, indicating that the US Department of Health and Human Services considered it to be an emerging issue.1 The document states that LGBT individuals encounter several health disparities linked to societal stigma, discrimination, and denial of human and civil rights. It also specifically mentions the need to provide medical students access to and training about LGBT patients to increase culturally competent care. As pharmacists are also an integral part of the healthcare system, this statement can be extrapolated to pharmacy students as well.

Although it is undeniable that the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations have significant challenges within the healthcare system, the struggles that transgender individuals face are even more pronounced. A transgender individual can include anyone whose self-identity, behavior, or anatomy falls outside of societal gender norms and expectations (Appendix 1). Transgender individuals have a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted diseases, mental health issues, and suicide.1 A significant number (28%) of transgender patients have experienced verbal harassment in a medical setting.2 Additionally, transgender individuals are less likely to have health insurance than heterosexual or LGB individuals. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, if necessary, can choose not to disclose their sexual orientation to their healthcare providers and still receive adequate primary health care. However, transgender patients must disclose their transgender status to receive thorough and appropriate health care. Yet, fear of discrimination by healthcare providers once they do disclose their status may prevent individuals from seeking both urgent and preventative medical treatment.2, 3 Knowledge of a patient’s transgender status increases the likelihood of discrimination and abuse by physicians.2 This insensitivity and hostility towards transgender patients is reinforced by inconsistent protection against discrimination in health care and insurance for transgender patients.4

To live their lives authentically, many transgender individuals pursue cross-gender hormone therapy. Transgender individuals who pursue this route must have strong relationships with all of their healthcare providers and be counseled by trained professionals on the risks and side effects associated with this therapy.5 There are few providers who have received the appropriate training and are knowledgeable about the specific healthcare needs of these individuals.2 Many transgender patients have to become experts about their own health care and often are the ones to educate their healthcare providers about transgender health issues. Transgender patients must also deal with the use of noninclusive language, errors in pronoun use, and the difficulties associated with filling out medical forms based on traditional gender identities.6,7

Given these barriers experienced by transgender patients, there is a significant need to educate future healthcare providers about their specific needs. Medical and nursing schools have begun to realize the need to reevaluate their curricula8,9 and to assess their students’ attitudes.10 However, to our knowledge, this assessment has yet to take place in the pharmacy curriculum.

Pharmacists must be culturally competent to provide adequate pharmaceutical care.11 The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) has emphasized the importance of cultural competency in the standards used for assessing all pharmacy programs. Standards 9 (the goal of the curriculum) and 12 (professional competencies and outcomes expectations) provide guidance related to the importance of cultural competency in providing the best patient-centered care.12 There is not a specific mention of LGBT-health-related issues, but these standards make it clear the value that ACPE places on cultural competency in the pharmacy curriculum. In 2011, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy hosted an institute entitled, “Cultural Competency: Beyond Race and Gender,” which specifically included LGBT issues as topics which have been underappreciated.13 However, to date, there are no pharmacy-specific resources available that would help guide pharmacists on how to effectively communicate with transgender patients.

There are approximately 950,000 transgender individuals in the United States14,15 and the likelihood that pharmacists will encounter transgender patients will increase as more transgender individuals live their lives authentically. It is up to healthcare providers to establish trust with transgender patients and to act in a sensitive and appropriate manner.16

To address these challenges, we developed and assessed a 2-hour panel discussion on transgender health care at the Wegmans School of Pharmacy at St. John Fisher College. We chose a panel discussion format to allow students to listen to real-life experiences from multiple speakers in an environment that welcomed questions. Previous research in pharmacy academia has shown that listening to guest speakers enhances student learning,17 and ACPE specifically recommends the use of guest speakers in Guideline 23.4.12 We examined the impact of this panel discussion on student knowledge about transgender patients and their experiences with the healthcare system. Additionally, we intended to gain information about how applicable students found the presentation to their pharmacy career.

DESIGN

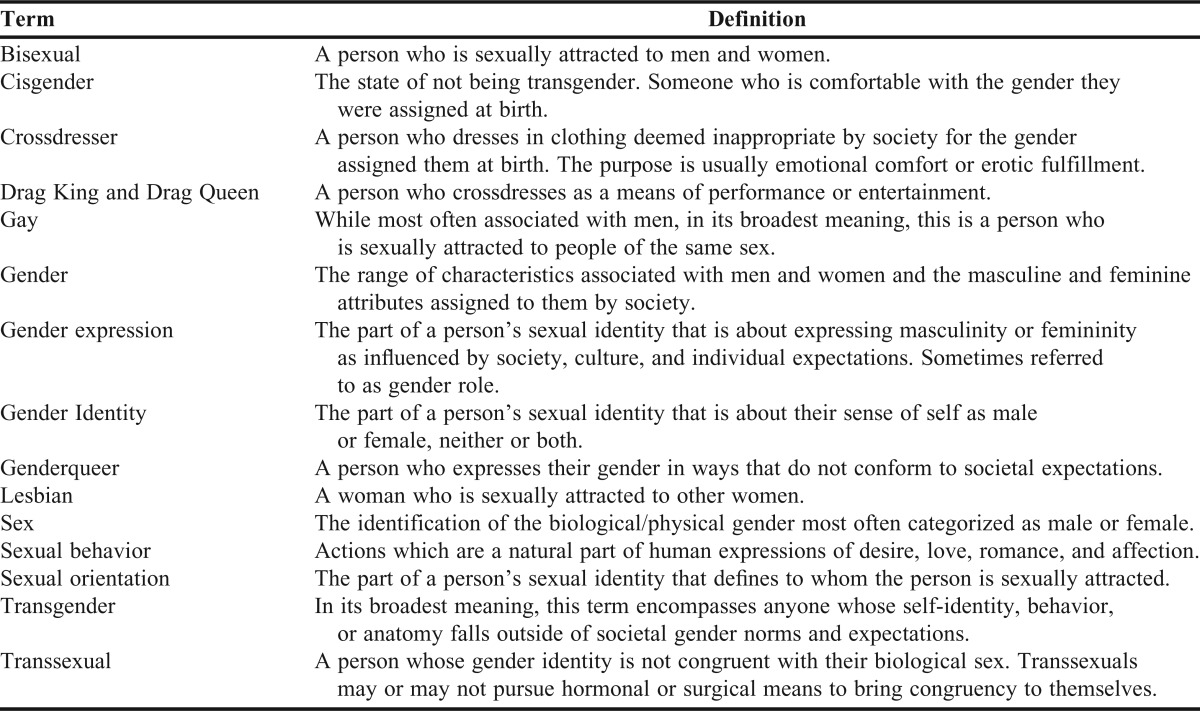

The panel discussion was a component of the required Introduction to Diversity course offered to P1 students in the 2012 spring semester. The course is composed of guest speakers, videos, interactive role-reversal exercises, and group discussions. Introduction to Diversity is a pass/fail course and the requirements of the course include attendance at every session, completion of 10 volunteer hours in a diverse setting, and written reflections on guest speaker presentations. The 79 participants in our study were enrolled in the course. This study consisted of a 1-hour introductory presentation on LGBT terminology, a 2-hour panel discussion, completion of 2 surveys, and a written reflection. Approval was granted by the St. John Fisher College Institutional Review Board prior to implementation of the study. Students attended a 60-minute presentation given by the Gay Alliance of Genesee Valley (GAGV) in which they were introduced to the appropriate LGBT terminology18 (Appendix 1) and were advised on how to respectfully interact with transgender individuals. Attendance at this mandatory presentation occurred 1 week prior to the panel discussion. Students were then given handouts developed by GAGV on “How to Respect a Transgender Person” and “Components of Human Sexual Identity” to take with them. Students were encouraged to think of questions to ask the panel during the in-class discussion. They could anonymously submit questions in a drop box placed in the back of the classroom for the moderator to ask during the panel discussion.

The moderator of the panel discussion was also the volunteer coordinator at GAGV and she directly recruited volunteers from their speaker’s bureau to participate as panelists. The panelists came from diverse backgrounds and experiences. The panel was composed of 2 male-to-female individuals and 2 female-to-male individuals in order to provide students with perspectives of both groups. Although not intentional, the panel was equally divided among panel members who were middle-aged and members in their early 20s.

The panel discussion began with the moderator asking panelists to introduce themselves and to share their experiences in the healthcare system. Specifically, the panel members discussed their personal experiences and any frustrations they had with pharmacists. The panelists also gave students suggestions on how to make interactions with transgender patients more productive. After these initial introductions, the open question-and-answer panel discussion began. Questions were posed by students in the class and the moderator also asked the panel members student-written questions that were presubmitted anonymously. Students asked both general (ie, When did you know that you were transgender?) and pharmacy-specific (ie, How do you discuss birth control with the transgender population?) questions during the open question-and-answer portion. The panel discussion lasted for 2 hours.

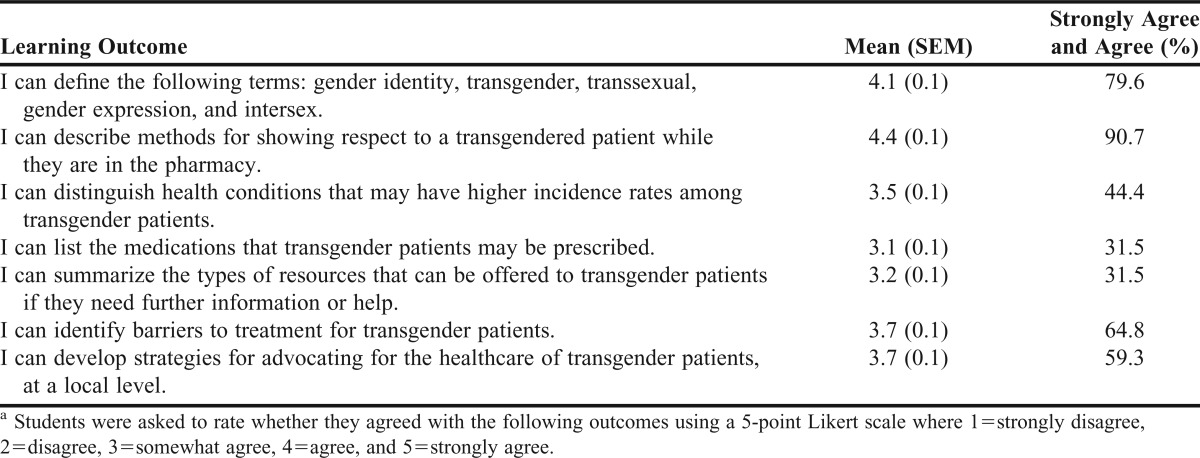

At the conclusion of the panel discussion, 2 surveys were distributed to the students. One survey was the standard instrument that GAGV created to use for all of their presentations. We developed the other survey instrument to address the learning outcomes of the exercise (Table 3). These learning outcomes were developed by the instructors of the course in collaboration with GAGV. The first learning outcome was specifically addressed in the introductory presentation by GAGV. All other learning outcomes were covered during the panel discussion. The GAGV survey instrument collected basic demographic information about the students and included questions about the content and usefulness of the presentation, the knowledge of the presenters, overall evaluation of the presentation, and students’ knowledge about LGBT topics before and after the presentation. Students were also asked to comment on the most important thing they learned.

Table 3.

Learning Outcomes of a Transgender Panel Discussion Within an Introduction to Diversity Coursea (n=58)

All surveys were anonymous. Students were told that completion of the survey instrument was voluntary and that they were free to leave any question unanswered. Survey instruments were collected in a covered labeled collection box that was in the front of the room. However, no one monitored which students turned in their survey instruments, and completion or noncompletion had no impact on the course. Because the surveys were voluntary, response rates varied.

As part of the course, students were required to write a 1- to 2-page reflection on their thoughts and feelings about the panel discussion. The reflections were due at the next class meeting, exactly 1 week after the panel discussion. Students were free to write about any aspect of the presentation as long as they wrote about their own thoughts on what was presented and did not simply provide a summary of what was covered. After the reflection papers were completed, students’ names were removed and the reflections were randomized. Reflections were numbered and analyzed for themes and, if appropriate, subthemes, as described below.

The data collected from the open-ended questions and student reflections were analyzed using qualitative analysis and a phenomenological study. The steps of analysis followed Creswell’s19 methodology, including “identifying significant statements, clustering themes, and ending with an essential invariant (essence) of the experience.” A phenomenological study was chosen because it reflected the meaning of a lived experience.20 Lived experiences are practical experiences that all members of a cohort go through together. Other phenomenological studies have taken the same approach when addressing the psychological meaning of a caring interaction.20 Theme analysis was conducted without the use of qualitative analysis software by a single researcher. After the initial analysis was complete, it was reviewed by 2 additional faculty members.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

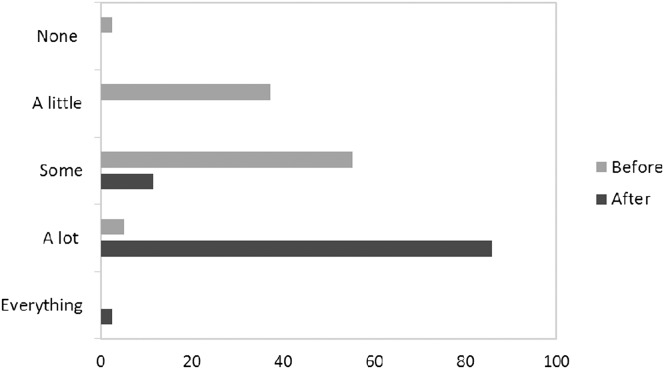

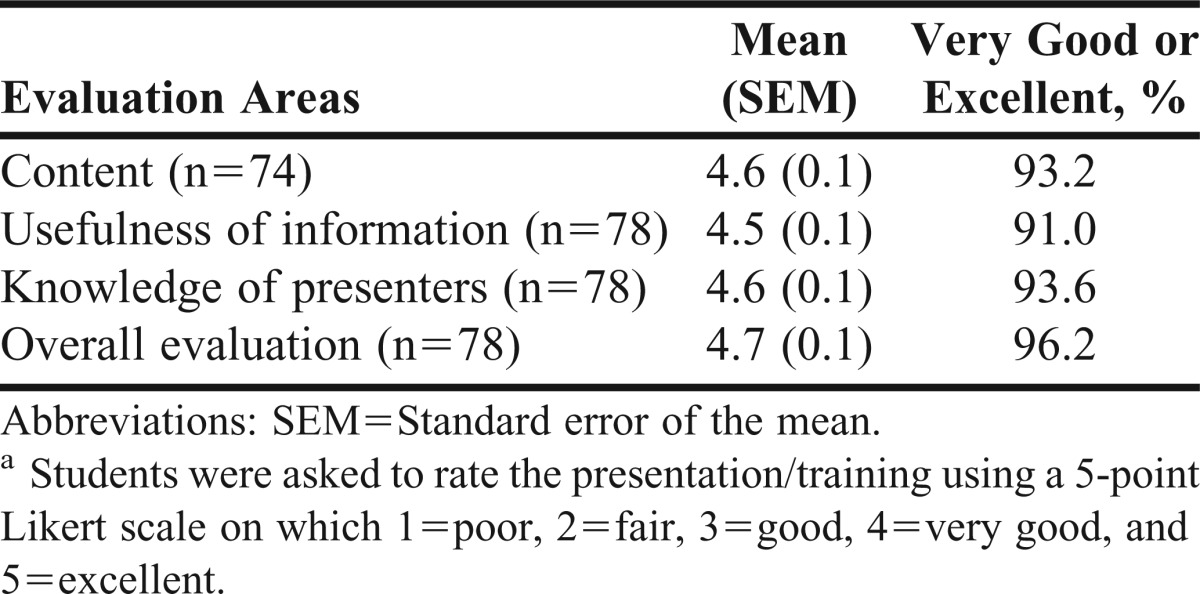

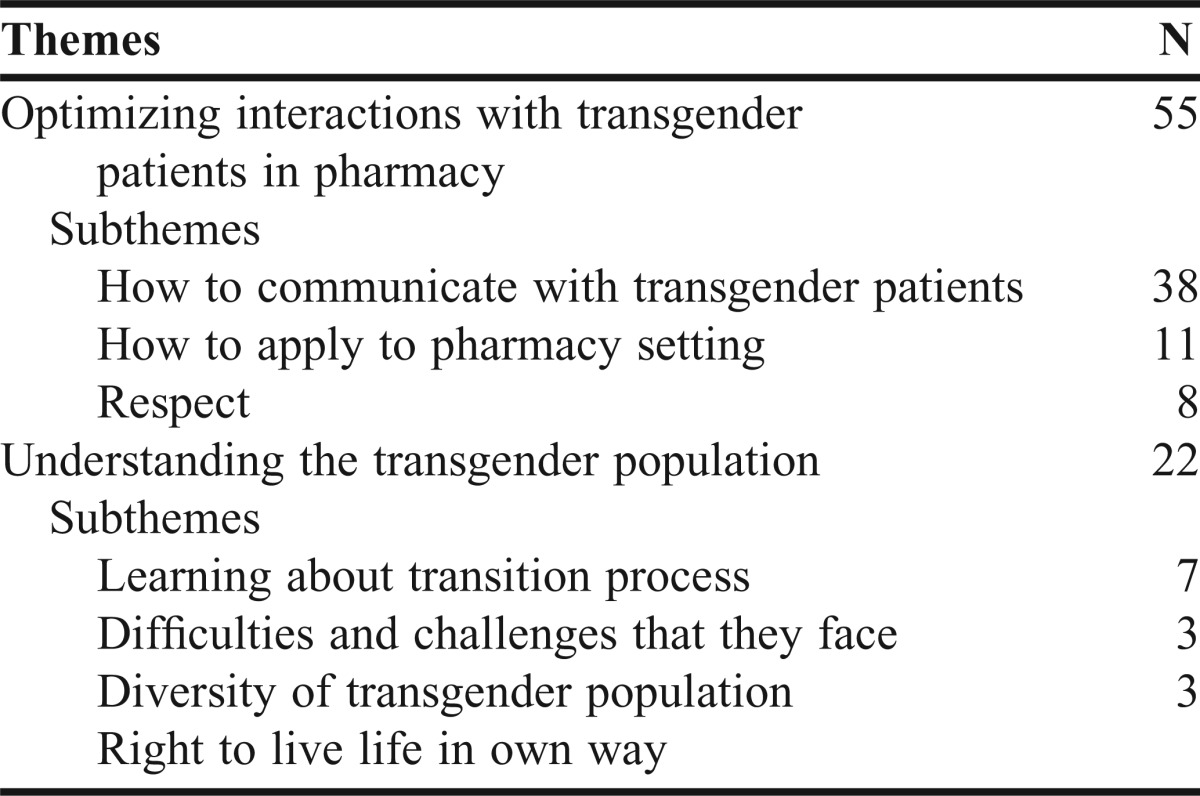

The survey developed by GAGV included evaluative questions on the presentation and the question, “How much did/do you know about gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender issues BEFORE and AFTER this presentation?” with response scale ranging from 1=none to 5=everything. Students were asked to provide feedback on the quality of the presentation content, the usefulness of the information, and the knowledge of presenters. Students also rated the overall presentation (Table 1). Although 78 students filled out the evaluation, not every student answered every question, which explained the discrepancies in the numbers of responses for each parameter. Students were overwhelmingly positive in their evaluations. Most students rated the overall quality and the usefulness of the presentation as very good or excellent (Table 1). There was a dramatic shift in the self-reported knowledge about LGBT issues after the presentation (Figure 1). After the presentation, students who had reported “none” or “a little” knowledge about LGBT issues dwindled to 0% and 86% of students reported that they knew “a lot.” The GAGV survey instrument also included the question, “What is the single most important thing you learned today?” Although students were asked to state only the single most important thing they had learned, several students listed 2 things they thought were important, which explains the discrepancy in total number of responses. The student responses were analyzed for themes, and the 2 major themes of “optimizing interactions with transgender patients in the pharmacy” and “understanding the transgender population” were identified (Table 2). These major themes were further divided into subthemes, with the subtheme “how to communicate with transgender patients” being the most frequently mentioned.

Table 1.

Evaluation of Presentation from Gay Alliance Surveya

Figure 1.

Student responses to “How much did/do you know about LGBT issues before and after this presentation?” (n=78)

Table 2.

Qualitative Analysis of Student Responses to “What is the single most important thing you learned today?”on the Gay Alliance of Genesee Valley Survey (n=66)

The learning outcomes survey was also distributed to the students after the panel discussion was completed. However, the response rate for this survey was not as robust as the GAGV survey (Table 3). Ninety one percent of students who completed the survey agreed that they could describe methods for showing respect to a transgendered patient; however, less than 50% of students agreed that they could perform learning outcomes 3, 4, and 5.

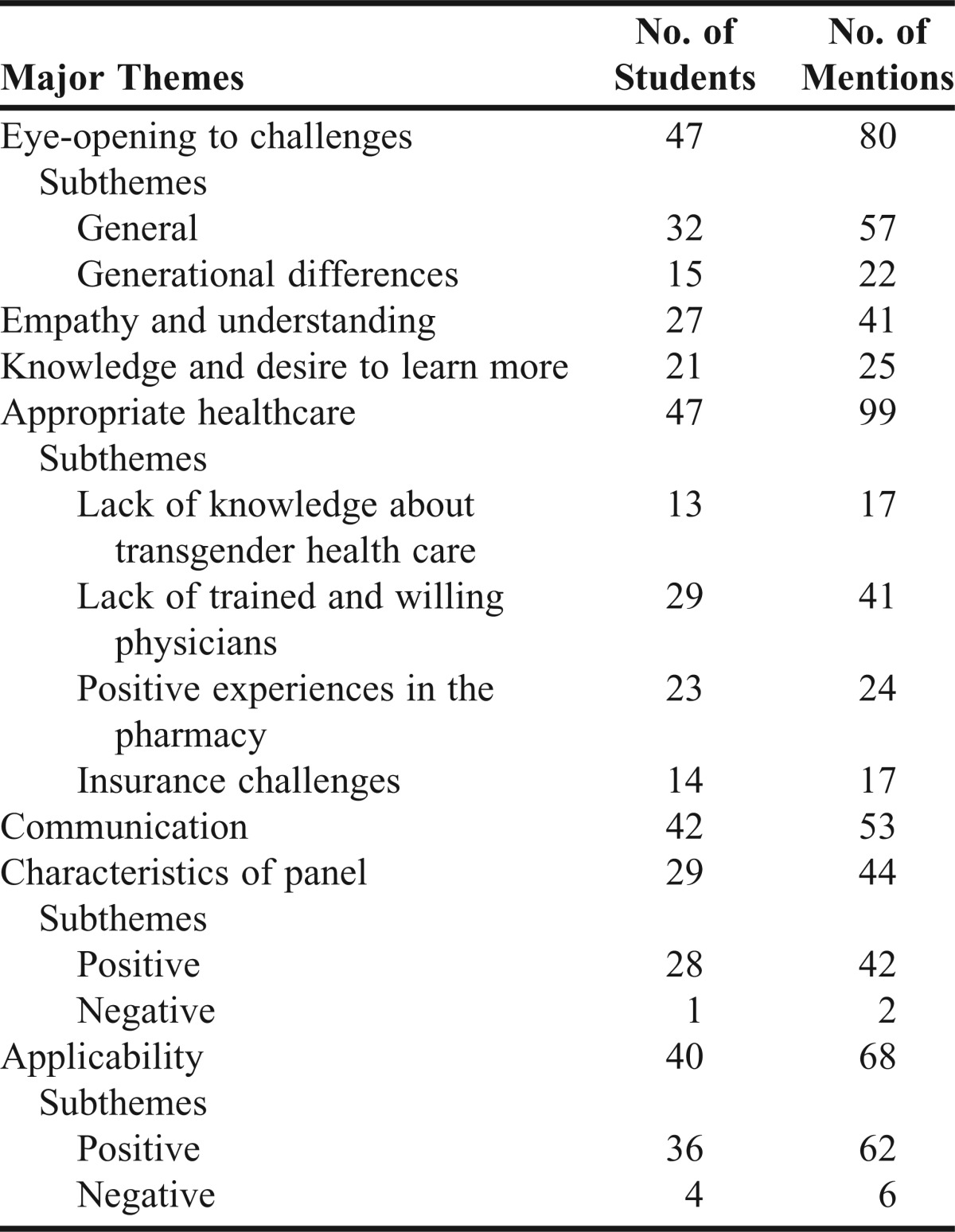

Qualitative analysis of the open-ended reflections (Table 4) revealed the following major themes that demonstrate student learning: “eye-opening to challenges,” “empathy and understanding,” “knowledge and desire to learn more,” “appropriate health care,” and “communication.” The major themes of “eye-opening to challenges” and “appropriate healthcare” were further subdivided into subthemes. The theme discussed the most was “appropriate healthcare.” Despite increased acceptance and visibility of the LGBT population in today’s society, “eye-opening to challenges” was frequently mentioned, indicating that a large percentage of our students lacked knowledge about this population. Additionally, students discussed how the panelists stimulated their desire to learn more about transgender patients. Students also provided evaluative data on the presentation in their 2-page written reflections. Two major themes were identified that pertained to evaluation of the presentation (Table 4). Most striking was the number of mentions that the panel discussion was applicable to students’ future career in pharmacy.

Table 4.

Qualitative Analysis of Major Themes and Subthemes Addressed in Student Reflections (n=79)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, few pharmacy schools address LGBT topics in their classroom-based curriculum or address transgender topics specifically. However, this is a population which is relevant to our students for 2 reasons: (1) pharmacists are more likely to have patients who are transgender because of the increasing number of transgender individuals in the United States,14,15 and (2) given the importance of medications to maintaining transgender patients’ quality of life, they will have to interact with pharmacists regularly.5 Each of these patient-pharmacist encounters is an opportunity to not only improve the health care that transgender patients receive but also to improve their perceptions of the healthcare system.

Students were shocked to hear the panelists say repeatedly that there were no healthcare providers in Rochester who specialized in transgender care. Many students felt embarrassed by this fact and talked about the small steps that they would take as pharmacists to address that issue.

After reading through the surveys and student reflections, it was clear that the panel discussion exceeded most of our expectations. Using both quantitative (Figure 1 and Table 3) and qualitative (Table 2 and Table 4) assessments, the panel discussion was found to be an effective approach to improve self-reported knowledge, awareness, and interest about transgender patients. Although LGBT individuals are more visible in today’s society than in the past, it was striking how many students commented on how eye-opening the discussion was (Table 4). Several students wrote that the panel discussion sparked a desire to learn more about transgender patients and their healthcare issues (Table 4). Specifically, after hearing the panel members speak, students were inspired to ask several questions on the risks and benefits of long-term hormonal therapy.

Qualitative analysis of open-ended survey questions (Table 2) and student reflections (Table 4) demonstrated that students felt the panel discussion was directly applicable to their future career in pharmacy. They also mentioned that the panel discussion provided a unique opportunity for them to gain that information.

There were also a few minor challenges encountered in the study. By making the self-reflections a course requirement, we may have created a situation that discouraged complete honesty. Students may have been writing what they thought their instructors wanted to hear and not what their real thoughts and feelings were. Although this possibility cannot be completely ruled out, negative comments were noted (Table 4), so some students were not afraid to be candid and express their true feelings on their experiences with the panel discussion.

While almost half of the students (Table 4) mentioned in their reflections how applicable the presentation was, the data on the learning outcomes survey (Table 3) indicated that less than half of students agreed with the statements “I can distinguish health conditions that may have higher incidence rates among transgender patients,” and “I can list the medications that transgender patients may be prescribed.” These low percentages likely reflected the open-ended nature of the panel discussion. Despite the concerted effort to have the panelists address medication regimens, students were free to ask any question, and several of those questions were not related to health care. The focus of the presentation was to get to know the panelists as individuals, and not solely focus on their gender status and their medications. Also, because the presentation was given during their first year, the pharmacy students had limited knowledge of clinical issues. We did not want the message of the presentation to be lost in clinical details that students did not yet have the training to understand. Further research is needed to determine whether this panel discussion would be more appropriately delivered in the second and/or third years after students have received training on endocrine pharmacotherapy.

We are planning to continue this panel discussion in the spring 2013 semester with a few minor modifications. We plan to decrease the length of the discussion from 2 hours to 90 minutes. Introduction to Diversity was the last class of the day, and we noticed that student engagement diminished in the last 30 minutes of the discussion. Decreasing the time to 90 minutes will allow sufficient time to discuss the relevant issues but will also help maintain student engagement. If students are interested to learn more, the panelists will answer additional questions afterwards. Also, by reducing the time of the panel discussion, 30 minutes can be added to the introductory session given by GAGV to better prepare students for the discussion.

We were overly ambitious about what could be accomplished in one 2-hour session, specifically with learning outcomes 3, 4, and 5 (Table 2). Given the students’ educational background and the informal nature of the panel discussion, these learning outcomes may not have been appropriate. Students have many preconceived notions about transgender individuals. Before specific questions on medication regimens could be asked and answered, these misconceptions needed to be addressed. One of the strengths of this presentation was that it allowed the student to question these misconceptions in a safe environment.

CONCLUSION

Inclusion of the transgender panel discussion improved pharmacy students’ perceptions of change in knowledge about transgender individuals. Both quantitative and qualitative data demonstrated that the students felt the panel discussion was applicable to a future career in pharmacy. Unfortunately, current training on transgender health care in pharmacy is limited. However, given the frequent patient encounters that pharmacists have with transgender patients, it is essential that colleges and schools of pharmacy provide the appropriate training, information, and resources to students to ensure that as pharmacists, they provide the best possible health care to this underserved patient population. Implementing a panel discussion like this could be the first step in closing the gap. Additional areas of focus could include incorporation of LGBT topics in pharmacy communication textbooks and studies that investigate pharmacists’ views on the LGBT population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jane Souza for her expert advice on qualitative analysis, and our wonderful panelists for their willingness to share their personal stories and experiences with our students.

Appendix 1.

Glossary of Terms Associated with the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Communities (Adapted with permission from the Gay Alliance of Genesee Valley.)18

REFERENCES

- 1.Healthy People. 2020, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health overview. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 2.Grant JM, Mottlet LA, Tanis J, Harrison L, Herman J, Keisling M. National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce; 2010. http://transequality.org/PDFs/NTDSReportonHealth_final.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newfield E, Hart S, Dibble S, Kohler L. Female-to-male transgender quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(9):1447–1457. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Report on the United States of America universal periodic review on sexual rights, 9th round. November 2010. http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/session9/US/JS10_JointSubmission10.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 5.Knezevich EL, Viereck LK, Drincic AT. Medical management of adult transsexual persons. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(1):54–66. doi: 10.1002/PHAR.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care. 2013;51(9):819–822. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829fa90d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planned Parenthood of the Southern Finger Lakes. Providing transgender-inclusive healthcare services. http://www.plannedparenthood.org/ppsfl/resources-transgender-inclusive-health-services-5156.htm. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- 8.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliason MJ, Dibble S, DeJoseph J. Nursing’s silence on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues. the need for emancipatory efforts. Adv Nur Sci. 2010;33(3):206–218. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181e63e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A. Medical students' ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med. 2006;38(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vess Halbur K, Halbur DA. Essentials of Cultural Competence in Pharmacy Practice. Washington, DC: The American Pharmacists Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 13.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Cultural Competency: Beyond Race and Gender. http://www.aacp.org/meetingsandevents/pastmeetings/2011Institute/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 14.Gates GJ. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute. http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 15.US Census Bureau. US and world population clock. http://www.census.gov/main/www/popclock.html. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- 16.Williamson C. Providing care to transgender persons: a clinical approach to primary care, hormones, and HIV management. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorek JA, Katz NL, Popovich NG. Guest speakers in a professional development seminar series. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(2):Article 28. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Gay Alliance. A glossary of terms associated with the LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) communities. http://www.gayalliance.org/images/stories/education/GlossaryofTerms-updatedAug2012.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2013.

- 19.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 2007. pp. 225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. 1st ed.