Abstract

Background

Beginning in 2009, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) revised its food packages and provided more whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, and fewer foods with high saturated fat content. However, knowledge of the impact of this policy shift on the diets of WIC participants remains limited.

Purpose

To examine the longer-term impact of the 2009 WIC food package change on nutrient and food group intake and overall diet quality among African American and Hispanic WIC child participants and their mothers/caregivers.

Methods

In this natural experiment, 24-hour dietary recalls were collected in the summer of 2009, immediately before WIC food package revisions occurred in Chicago, Illinois, and at 18 months following the food package change (winter/spring 2011). Generalized estimating equation models were used to compare dietary intake at these two time points. Data were analyzed in July 2013.

Results

Eighteen months following the WIC food package revisions, significant decreases in total fat (p=0.002) and saturated fat (p=0.0004) and increases in dietary fiber (p=0.03), and overall diet quality (p=0.02) were observed among Hispanic children only. No significant changes in nutrient intake or diet quality were observed for any other group. The prevalence of reduced-fat milk intake significantly increased for African American and Hispanic children, whereas the prevalence of whole milk intake significantly decreased for all groups.

Conclusions

Positive dietary changes were observed at 18-months post-policy implementation, with the effects most pronounced among Hispanic children.

Introduction

Approximately one in eight preschoolers (aged 2–5 years) in the U.S. are classified as obese (BMI≥95th percentile), with low-income and some racial/ethnic minorities (e.g., African American and Hispanic) experiencing even higher rates.1,2 The burden of childhood obesity requires solutions to address this major public health problem on a population level.3 In an effort to improve diet and address the high rates of obesity among children living in poverty, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) revised its food packages to be consistent with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.4–7 These revisions provided more whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, and fewer foods with high saturated fat content. These were the first food package changes in the WIC program since its inception approximately 40 years ago.7 With nearly nine million WIC participants in 20128 and close to half of all infants in the U.S. having participated in the program, the reach of WIC is considerable and understanding the impact of this policy change is vital.

To date, published findings have reported the influence of the WIC policy change on access and availability of healthful foods in neighborhoods,9–12 vendor practices and beliefs,13,14 breastfeeding initiation and infant feeding decisions,15,16 and juice and beverage purchases.17 Knowledge of how this policy change impacts the diets of WIC recipients, particularly young children (aged 2–4 years), is beginning to emerge.18–20 Both Whaley et al. and Odoms-Young et al. examined the initial impact of this policy change (6 months after) on diet. Whaley et al.’s cross-sectional comparison assessed the frequency of fruit, vegetable, whole grain, and milk (whole and low-/non-fat) intakes of WIC recipients (n=3,004 in September 2009, n=2,996 in March 2010).18 Overall, respondents reported increases in whole grains, vegetables, and low-fat milk and a decrease in whole milk. Odoms-Young and colleagues’ prospective study assessed diet change among African American and Hispanic mother–child dyads in WIC, where they also observed decreased whole milk intake and increased low-fat milk intake; however, whole grain intake only increased among Hispanic children, and fruit consumption improved solely among Hispanic mothers.19 Only one published study evaluated the impact of the WIC policy change on diet beyond 6 months. Chiasson et al.’s cross-sectional study reviewed 3.5 million WIC administrative records from New York state at 6-month intervals from July to December 2008 to December 2011 and assessed dietary intake from a brief food frequency questionnaire (yes and no responses).20

In this current study, the longer-term impact (>6 months) of the revised WIC food package on the diets of WIC recipients was also assessed. However, this was the first study to prospectively follow a cohort of Hispanic and African American WIC recipients (children aged 2–4 years) and their mothers over an 18-month interval and to assess the impact of these revisions on diet using 24-hour dietary recalls. These findings build upon earlier work19 which evaluated the initial impact of these revisions on the diets of Hispanic and African American mother–child dyads.

Methods

Design and Setting

Implementation of the revised WIC food packages began in August 2009 in Chicago, Illinois. Prior to changes that summer (2009), parent–child dyads were recruited from 12 WIC centers throughout the city of Chicago to participate in a cross-sectional survey of dietary intake and other lifestyle measures. Subsequently, participants from the cross-sectional study were invited to enroll in a longitudinal study, where the primary aim was to assess diet changes over an 18-month interval (pre- and post-policy implementation). The visits occurred in winter/spring 2010, fall 2010, and winter/spring 2011, respectively. Findings from the cross-sectional study and at the 6-month follow-up were published previously.19,21

This article examined dietary changes prior to policy revisions (summer 2009) and 18 months after implementation (winter/spring 2011). The period before policy revisions occurred is referred to as “baseline.” All study procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago’s IRB and participants provided signed informed consent.

Participants and Eligibility

Parent–child dyads were eligible for the longitudinal study if the child was aged between 2 and 3.5 years at baseline and participating in WIC. This age range was chosen to ensure that the child would be eating solid foods and would still be eligible for WIC (<5 years old) at the 18-month visit. Parents or guardians with a child enrolled in WIC were eligible if they were fluent in either English or Spanish.

Analytic sample

Overall, 295 parent–child dyads consented to participate in the longitudinal study. At 18 months, 28 dyads were lost to follow-up and 25 were ineligible because they no longer had a child enrolled in WIC. Greater than 90% of adults in the overall study sample were women and self-identified as either African American or Hispanic (n=275 at baseline, n=222 completed data collection at 18 months). Therefore, this analytic sample was restricted to eligible African American and Hispanic children and their mothers or female caregivers with valid diet data at baseline and 18 months. A recall was “invalid” if: (1) the entire recall was missing; (2) an implausible amount of calories was reported (adults only, <500 kcals or >5000 kcals); or 3) one or more main meals were missing (mainly from child being at daycare). As a result, 209 mothers (Hispanic, n=112; African American, n=97; 13 excluded for invalid diets) and 164 children (Hispanic, n=94; African American, n=70; 58 excluded for invalid diets) were included in this analytic sample.

Measures

Trained interviewers administered all questionnaires. All Hispanic participants were interviewed by bilingual interviewers (fluent in English and Spanish) in the language of their choice.

Household participation in WIC

At the 18-month visit, mothers were asked how many household members received WIC benefits in the past 6 months. The fruit and vegetable voucher amount was calculated from this information. Each child enrolled in WIC received $6/month and each pregnant or postpartum/breastfeeding woman received $10/month.22 Thus, a household with one child enrolled in WIC received $6 and a household with ≥ two individuals enrolled received >$6/month.

Acculturation

Mothers who identified as Hispanic/Latina completed the 4-item Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH)23 at baseline. The score was derived from a mean of four items, with responses ranging from 1 (least acculturated) to 5 (most acculturated). An average score <3 represents “less-acculturated” respondents.

Anthropometric variables

Children’s and mothers’ heights and weights were collected at 18 months in participants’ homes or at WIC clinics. Regardless of location, all measurements were obtained by trained data collectors using a portable stadiometer and digital scale. Participants removed shoes and heavy outer clothing prior to measurements. Heights and weights were measured twice and averaged. BMI was computed from these measurements (kg/m2).

Dietary intake

One 24-hour dietary recall was collected for each mother and child at baseline and at 18 months, respectively. Children’s diets were reported by proxy via the mother. Recalls were conducted by trained interviewers using a multiple-pass approach.24 The respondent was asked to recall all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours, including time and type of meal, portions consumed, and details about food preparation. Booklets showing standard food measurements were used to improve accuracy of portion-size recall. All 24-hour dietary recalls were entered and processed using Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR), 2009 (Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota).

The food group variables created by NDSR calculated fruit consumption, 100% fruit juice, vegetables, milk, whole grains, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). “Fruits” included citrus and non-citrus fruits and excluded juices, avocado, fried fruits, and fruit-based savory snacks. Fruit juices (100%) were reported separately. “Vegetables” included all non-starchy and starchy vegetables, including avocado and legumes, and excluded fried potatoes and fried vegetables. A food was categorized as a “whole grain” if a whole grain ingredient was the first ingredient on the food label. Foods containing “some whole grain” were included in the summary variables with a weighting of 0.5. SSBs included soft drinks, fruit drinks, sweetened teas, sweetened coffee, sweetened water, and sports drinks. Serving sizes for the food group variables were based on the recommendations made by the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.25 For foods not included in dietary recommendations (e.g., cookies, candy, and others), Food and Drug Administration (FDA) serving sizes were used (NDSR Manual 2009, Appendix 10).

Diet Quality

The Healthy Eating Index 2005 (HEI-2005)26,27 measures diet quality based on compliance with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans4 and includes the 12 following components: total fruit, total vegetables, dark green and orange vegetables and legumes, whole grains, total grains, milk, meat and beans, oils, saturated fat, sodium, and calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars. The total HEI score is the sum of component scores with a maximum value of 100. Scores are calculated using an energy-density approach (e.g., intake of food component per 1000 calories). Higher scores reflect better compliance with dietary guidelines.4

Statistical Analyses

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models28 were used to examine diet (i.e., food groups, nutrients, and diet quality) from baseline to 18 months for children and mothers by race/ethnicity (i.e., African American and Hispanic). Models controlled for age, gender (children only at baseline), total voucher amount per household (i.e., $6/month or >$6/month), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) use (yes or no), BMI status (children, <85th percentile or ≥85th percentile; adults, BMI <30 kg/m2 or ≥30 kg/m2), and mother’s acculturation status at baseline (Hispanics only, score <3 or ≥3). Adjustment variables were collected at 18 months unless otherwise specified. Total calories (kcals), percent calories from fat, percent calories from saturated fat, dietary fiber (g/1000 kcals), and HEI-2005 diet quality score were analyzed as continuous variables and presented as adjusted means. Food group variables were dichotomized to account for the large number of zero values observed across all food groups and logistic GEE models were used to examine proportions at each time point. For milk, fruits, fruit juices, whole grains, and SSBs, the proportions (adjusted) of individuals reporting >zero servings/day for these variables were presented. Unlike fruit intake, most individuals (range=81%–97%) reported some vegetable intake (>0 servings) on a given day; therefore, the proportion (adjusted) of individuals reporting ≥0.5 servings/day (per 1000 kcals) was presented. Two percent, 1%, and skim milk intake were combined into one “reduced-fat milk” category because only a small percentage of individuals (approximately 1%) reported consuming 1% or skim milk. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05, and all analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Characteristics

African American and Hispanic mothers were similar in age and employment status (Table 1). The acculturation level among Hispanic mothers was low (79% scored <3 on SASH, 78% interviewed in Spanish). In addition to WIC, most households (80%–93%) received SNAP benefits. The average child age was 52 months. Fifty-three percent of Hispanic children and 30% of African American children were overweight (BMI≥85th percentile) and most mothers were either overweight or obese (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers and children by race/ethnicity

| Hispanic | African American | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mothers | n=112 | n=97 |

| Age in years,a M (SD) | 31.4 (5.6) | 32.2 (9.8) |

| High school graduate,b n (% yes) | 56 (50%) | 77 (79%) |

| Married/living with partner,b n (% yes) | 90 (80%) | 21 (22%) |

| Employed full-time,b n (% yes) | 13 (12%) | 14 (15%) |

| Acculturation,b,c n (% score <3) | 89 (79%) | – |

| Interviewed in Spanish | 87 (78%) | – |

| Children aged <18 years in household,a n (%) | ||

| 1–2 children | 54 (48%) | 52 (54%) |

| >2 children | 58 (52%) | 45 (46%) |

| Number of adults in household,a n (%) | ||

| 1 adult | 11 (10%) | 37 (38%) |

| ≥2 adults | 101 (90%) | 60 (62%) |

| Fruit and vegetable voucher amount per household,a n (%) | ||

| $6/month | 57 (51%) | 50 (52%) |

| >$6/month | 55 (49%) | 47 (48%) |

| SNAP or other cash assistance in last 6 months,a,e n (%) | 90 (80%) | 90 (93%) |

| BMI,d kg/m2, M (SD) | 31.0 (6.9) | 30.8 (7.1) |

| BMI category,d n (%) | ||

| Overweight (25 <30 kg/m2) | 42 (39%) | 26 (31%) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 49 (45%) | 41 (49%) |

| Children | n=94 | n=70 |

| Girls,b n (%) | 50 (53%) | 37 (53%) |

| Age,a months, M (SD) | 52.0 (5.8) | 52.8 (5.3) |

| BMI≥85th percentile,a,f n (%) | 47 (53%) | 19 (30%) |

Note: Includes participants with valid diet data at baseline and 18 months.

Measured at the 18-month visit.

Measured at baseline.

From Marin scale; higher score=greater acculturation (range=1–5).

If parent BMI was not measured at the 18-month visit, the value from the 12-month visit was used. n=109 for Hispanic mothers and 84 for African American mothers.

SNAP refers to cash assistance from federal assistance programs based on income-related eligibility

BMI variable, n=89 for Hispanic children and 64 for African American children. SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Nutrient Intake and Diet Quality

No significant changes in nutrient intake and overall diet quality were observed for mothers. However, a trend toward lower saturated fat and higher fiber intake was found among Hispanic mothers and increased HEI-2005 score was observed among African American mothers (Table 2). African American children increased their energy intake over time, but no other significant changes were observed. In contrast, Hispanic children improved in all nutrient categories and in diet quality. Specifically, decreases in fat (% change= −10.5%, p=0.002), saturated fat (% change= −15.3%, p=0.0004), and increases in fiber (% change= 17.1%, p=0.03) and HEI-2005 score (% change= 7.2%, p=0.02) were observed.

Table 2.

Nutrient intake and diet quality before and 18-months after food package revisions

| Children

|

Mothers

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 18 months | Baseline | 18 months | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Energy (kcals) | Ma | SE | Ma | SE | Change (%)b | pc | Ma | SE | Ma | SE | Change (%)b | pc |

| African American | 1130.6 | 57.1 | 1366.7 | 62.3 | 20.9 % | 0.003 | 1925.0 | 120.4 | 1796.3 | 104.3 | −6.7 % | 0.21 |

| Hispanic | 1038.7 | 62.6 | 1193.9 | 61.9 | 14.9 % | 0.004 | 1562.2 | 65.4 | 1543.6 | 70.1 | −1.2 % | 0.76 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total fat (%kcals) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| African American | 31.6 | 2.7 | 33.2 | 2.3 | 5.0% | 0.27 | 39.2 | 1.6 | 38.0 | 1.7 | −3.0 % | 0.38 |

| Hispanic | 33.6 | 1.1 | 30.1 | 1.2 | −10.5% | 0.002 | 32.2 | 1.0 | 30.8 | 1.1 | −4.3 % | 0.24 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Saturated fat (% kcals) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| African American | 11.0 | 1.2 | 10.6 | 1.1 | −3.6 % | 0.55 | 13.3 | 0.7 | 12.6 | 0.7 | −5.1 % | 0.22 |

| Hispanic | 12.5 | 0.5 | 10.6 | 0.6 | −15.3% | 0.0004 | 11.2 | 0.5 | 10.2 | 0.5 | −9.0 % | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fiber (g/1000 kcals) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| African American | 6.3 | 0.3 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 5.7% | 0.38 | 6.9 | 0.4 | 7.4 | 0.5 | 7.4% | 0.22 |

| Hispanic | 7.4 | 0.6 | 8.6 | 0.6 | 17.1 % | 0.03 | 9.6 | 0.6 | 10.9 | 0.8 | 12.9 % | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Healthy Eating Index | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| African American | 51.8 | 1.8 | 53.6 | 1.8 | 3.5% | 0.32 | 43.7 | 1.3 | 46.2 | 1.3 | 5.8% | 0.13 |

| Hispanic | 55.6 | 1.9 | 59.6 | 1.9 | 7.2 % | 0.02 | 57.3 | 1.3 | 58.1 | 1.5 | 1.4% | 0.62 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Baseline, 24-hour dietary recalls were collected immediately prior to implementation of the revised WIC food package in August 2009 in Chicago IL; 18 months, 24-hour dietary recalls were collected 18-months post policy change.

Generalized estimating equation models computed adjusted means. Models controlled for age at 18 months, gender (children only), total voucher amount per household at 18 months (i.e., $6/month or >$6/month), SNAP status (yes or no) at 18 months, BMI status (children <85th percentile or ≥85th percentile, adults: BMI <30 or ≥30) at 18 months, and acculturation status (for Hispanics only, score <3 or ≥3) at baseline.

Change (%): Percent change from baseline to 18 months.

p compares mean change from baseline to 18 months. n=89 Hispanic children, n=64 African American children; n=109 Hispanic mothers, n=83 African American mothers.

Food Group Intake

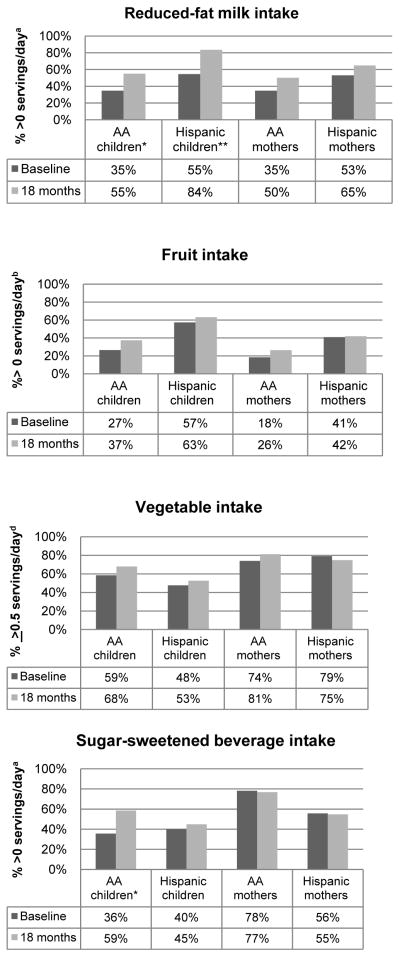

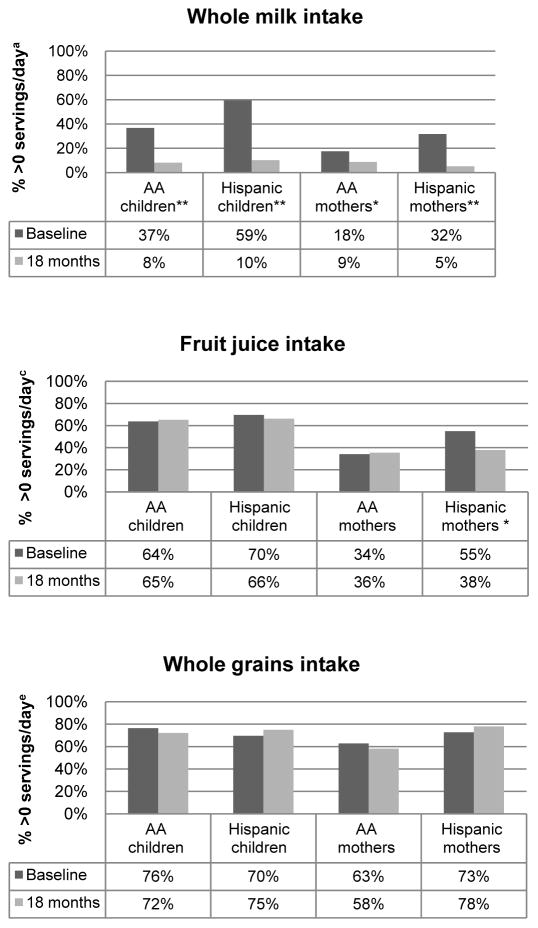

More children drank reduced-fat milk at 18 months compared to baseline (African American, 35%–55%, p<0.05; Hispanic: 55% to 84%, p<0.001) and a similar trend was observed for mothers (Figure 1). All groups significantly reduced their whole milk intake. While African American children drank less whole milk; they also significantly increased their consumption of SSBs (36%–59%, p=0.01). Hispanic mothers decreased their fruit juice intake (55%–38%, p<0.001). No significant changes were observed in any other food groups.

Figure 1.

Proportion of food group intake before and 18 months after food package revisions

Note: Baseline, 24-hour dietary recalls were collected immediately prior to implementation of the revised WIC food package in August 2009 in Chicago IL; 18 months, 24-hour dietary recalls were collected approximately 18 months after the revised WIC food package changes occurred. Logistic generalized estimating equation models computed adjusted proportions. Models controlled for age at 18 months, gender (children only), total voucher amount per household at 18 months (i.e., $6/month or >$6/month), SNAP status (yes or no) at 18 months, BMI status (children, <85th percentile or ≥85th percentile; adults, BMI <30 or ≥30) at 18 months, and acculturation status (for Hispanics only, score <3 or ≥3) at baseline.

aOne serving=8 fluid ounces. “Reduced-fat” milk includes 2%, 1%, and non-fat milk. bOne serving is 1 medium piece of fruit, 1/4 cup of dried fruit, 1/2 cup fresh, frozen canned fruit, or 1/2 fresh grapefruit; excludes juices, avocado, and fried fruits. cOne serving=4 fluid ounces. dOne serving is 1 cup of raw leafy vegetables, 1/2 cup of other cooked or raw vegetables, or 1/2 cup of vegetable juice; excludes fried potatoes and vegetables. Units are based on >0.5 servings/day per 1000 kcals. eOne serving is one slice of bread, 1 ounce of ready-to-eat cereal, or 1/2 cup cooked cereal, rice, or pasta.

*p<0.05, **p<0.001, compares proportions at baseline to proportions at 18 months. AA, African American; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Discussion

The unprecedented 2009 WIC national policy revision has the potential to promote healthful eating among low-income populations and may reduce diet-related health disparities, including obesity.7 The current investigation assessed the longer-term impact of these revisions on the diets of African American and Hispanic mother–child dyads. This study found improvements in intakes of total fat, saturated fat, fiber, and overall dietary quality among Hispanic children. In addition, the prevalence of reduced-fat milk intake significantly increased for African American and Hispanic children, and the prevalence of whole milk intake significantly decreased for all groups.

Dietary changes were most prominent among Hispanic children. Similar to earlier 6-month findings,19 significant improvements in fiber, fat, and saturated fat intakes were still evident at 18 months. Diet quality scores also increased. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2004) suggests overall diet quality typically decreases with age among preschoolers,29,30 which seems to indicate that improvements were influenced by the food package revisions rather than expected change due to child growth. Among low-income preschoolers, ethnic identity is a good positive predictor of diet quality, particularly among those of Mexican descent.31 As these improvements were not also observed among African American children, acculturation likely also played a role. In this less-acculturated sample, Hispanic children may have been more likely to consume a “traditional” Mexican diet, which is thought to be rich in higher-fiber foods (e.g. beans and corn tortillas).32 This is further supported by the high proportion of Hispanic mothers and children in this sample reporting whole grain intake prior to (70%–73%) and after package revisions (75%–78%).

Some of the changes in dietary behavior appear to be directly associated with WIC food package changes. Similar to previous studies, whole milk consumption decreased18,19 and lower-fat milk intake increased18–20 after whole milk was removed from the child (age >2 years) food package and replaced with low-fat milk options. Offering low-fat milk as the “default” option potentially made it easier for WIC recipients to adopt this change. Behavioral economics suggest that individuals are biased towards the default because it is perceived as less burdensome.33–35 Low-income individuals already face additional barriers (e.g., economic and structural) to healthful eating;36 therefore, greater attention should be placed on policies that attempt to normalize access to healthy foods. Unlike milk intake, reported intake of whole grains improved minimally. One reason for not observing significant improvements may be the high proportion of individuals (>70%), particularly Hispanic mothers and children, already consuming whole grains prior to revisions. In comparison, Chiasson et al. found an overall improvement in whole grain consumption; however, their findings varied widely by race/ethnicity (e.g., Non-Hispanic white, 77%; Asian, 38.9%) and they did not specifically comment on whole grain intake among Hispanic or African American children.

Among African American children, changes in milk intake were also coupled with an increase in SSBs. Given that the largest increase in caloric contribution from SSBs has been seen in children aged between 6 and 11 years,37 the increase in SSBs among this sample of high-risk children aged <5 years is of concern. Among a sample of children participating in the National School Lunch Program (n=2,314), a higher consumption of SSBs in addition to lower milk intake was observed significantly more often among African American compared to Hispanic and non-Hispanic white students.38 Evidence from both observational and experimental studies suggests that the regular intake of SSBs contributes to excess weight gain for both children and adults.39–41 Consequently, it is important to consider policy and programmatic strategies that would incentivize decreasing SSB intake. Various approaches have been suggested, including taxing SSBs,42 restricting the ability to purchase SSBs through SNAP,43 limiting the marketing of SSBs to children,44 and increasing neighborhood availability of healthful beverage and food options.45 Furthermore, a majority of participants in this study also participated in SNAP, the largest of the federal food assistance programs in the U.S.46,47 Therefore, better coordination of efforts between all federal food assistance programs and further alignment with dietary guidelines could facilitate healthier beverage choices.

Since lower-income populations tend to consume fewer fruits and vegetables than those of higher income,48–50 the inclusion of a fruit and vegetable voucher was a highly anticipated change. However, improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption were minimal across all groups. Given that the median monthly voucher amount for the sample was $6, this relatively small voucher amount may have been insufficient to produce a notable increase in intake for any individual family member. Results from a study of Herman et al.51 suggest that a larger voucher amount may be necessary to influence fruit and vegetable consumption and is an issue that deserves increased attention especially lower-income minorities. For instance, Chiasson et al. found overall improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption; however, fruit intake was lowest among African American children and vegetable intake was lowest among Hispanic children.20 In this study, 74% and 63% of the African American mothers and children, respectively, reported no fruit intake on a given day. Although fruit and vegetable consumption was better among Hispanic families, few mothers (approximately 10%) or children (approximately 20%) met the minimum federal guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake (data not shown).

The findings of this study also need to be considered in light of its limitations. This was a natural experiment with no control group for comparison and the sample is not representative of all Hispanic and African American children in WIC. Owing to resource limitations, only one 24-hour recall was collected, which does not fully characterize usual dietary intake, and children’s meals consumed at daycare could not be taken into account.

Despite recent evidence suggesting obesity among low–income preschool aged children is declining in some states in the U.S.,52 obesity continues to be a critical public health concern. Numerous factors can exert modest effects on daily energy balance culminating in either weight management or excessive weight gain over time.53,54 Policy changes, such as the 2009 WIC food package revisions, that influence individual behavior and provide reciprocal reinforcement can make it easier for families with young children to make healthier choices, and ultimately have an impact on obesity.55

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute (RC1CA149400, R25CA067699, P50CA106743, and P60MD003424) and the department of Kinesiology and Nutrition at the University of Illinois. We would like to thank Catholic Charities, particularly, Angel Gutierrez and Doris Wilson for their support, as well as the Chicago Department of Public Health, Near North Health Services, TCA Health, Inc., and the staff at the WIC clinics and WIC Food and Nutrition centers. We also appreciate the time that the WIC participants gave us by participating in this study. Finally, we would like to thank Stephen Onufrak from the CDC for developing the SAS program used for calculating the Healthy Eating Index.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the U.S —gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IOM. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.USDHHS, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2005 health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/

- 5.U S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): revisions in the WIC food packages; interim rule. Fed Reg. 2008;72(234):68965. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): revisions in the WIC food packages; delay of implementation date. Fed Reg. 2008;72(52):14153. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IOM. WIC food packages: time for a change. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. WIC Program Participation and Costs. fns.usda.gov/pd/wisummary.htm.

- 9.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Middleton AE, Long MW, Schwartz MB. Positive influence of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food packages on access to healthy foods. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):850–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillier A, McLaughlin J, Cannuscio CC, Chilton M, Krasny S, Karpyn A. The impact of WIC food package changes on access to healthful food in 2 low-income urban neighborhoods. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(3):210–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havens EK, Martin KS, Yan J, Dauser-Forrest D, Ferris AM. Federal nutrition program changes and healthy food availability. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(4):419–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenk SN, Odoms-Young A, Powell LM, et al. Fruit and vegetable availability and selection: federal food package revisions, 2009. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(4):423–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreyeva T, Middleton AE, Long MW, Luedicke J, Schwartz MB. Food retailer practices, attitudes and beliefs about the supply of healthy foods. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(6):1024–31. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Andreyeva T, et al. Small retailer perspectives of the 2009 Women, Infants and Children Program food package changes. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(5):655–65. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.5.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whaley SE, Koleilat M, Whaley M, Gomez J, Meehan K, Saluja K. Impact of policy changes on infant feeding decisions among low-income women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):2269–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilde P, Wolf A, Fernandes M, Collins A. Food-package assignments and breastfeeding initiation before and after a change in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(3):560–66. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Tripp AS, Henderson KE. Effects of reduced juice allowances in food packages for the Women, Infants, and Children Program. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):919–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whaley SE, Ritchie LD, Spector P, Gomez J. Revised WIC food package improves diets of WIC families. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(3):204–09. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odoms-Young AM, Kong A, Schiffer LA, et al. Evaluating the initial impact of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food packages on dietary intake and home food availability in African-American and Hispanic families. Public Health Nutr. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiasson MA, Findley SE, Sekhobo JP, et al. Changing WIC changes what children eat. Obesity. 2013;21(7):1423–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong A, Odoms-Young AM, Schiffer LA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in dietary intake among WIC families prior to food package revisions. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) revisions in the WIC food packages rule to increase cash value vouchers for women. Fed Reg. 2009;74(250):69243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Procedures for collecting 24-hour food recalls. Washington DC: U.S Department of Agriculture; www.csrees.usda.gov/nea/food/efnep/ers/documentation/24hour-recall.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Agriculture and USDHHS. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, Appendix A-2. USDA Food Guide. health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/html/appendixA.htm.

- 26.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(11):1896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller PE, Mitchell DC, Harala PL, Pettit JM, Smiciklas-Wright H, Hartman TJ. Development and evaluation of a method for calculating the Healthy Eating Index-2005 using the Nutrition Data System for Research. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(2):306–13. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diggle P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford England: Clarendon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole N, Fox MK. Diet quality of American young children by WIC participation status: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2008. www.fns.usda.gov/ora/menu/Published/WIC/FILES/NHANES-WIC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Zanovec M, Cho SS, Kleinman R. Consumption of whole grains is associated with improved diet quality and nutrient intake in children and adolescents: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Public Health Nutr. 2010;14(2):347–55. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kranz S, Findeis JL, Shrestha SS. Use of the Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index to assess preschooler’s diet quality, its sociodemographic predictors, and its association with body weight status. Jornal de Pediatria. 2008;84(1):26–34. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batis C, Hernandez-Barrera L, Barquera S, Rivera JA, Popkin BM. Food acculturation drives dietary differences among Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Non-Hispanic whites. J Nutr. 2011;141(10):1898–906. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.141473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson E, Bellman S, Lohse G. Defaults, framing and privacy: why opting in-opting out. Mark Lett. 2002;13(1):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loewenstein G, Brennan T, Volpp KG. Asymmetric paternalism to improve health behaviors. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2415–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wootan MG. Children’s meals in restaurants: families need more help to make healthy choices. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):31–3. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among U.S children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1604–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dodd AH, Briefel R, Cabili C, Wilson A, Crepinsek MK. Disparities in consumption of sugar-sweetened and other beverages by race/ethnicity and obesity status among U.S. schoolchildren. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(3):240–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeBoer MD, Scharf RJ, Demmer RT. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in 2- to 5-year-old Children. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):413–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Khan T, Wada R, Chaloupka FJ. Assessing the potential effectiveness of food and beverage taxes and subsidies for improving public health: a systematic review of prices, demand and body weight outcomes. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):110–28. doi: 10.1111/obr.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shenkin JD, Jacobson MF. Using the Food Stamp Program and other methods to promote healthy diets for low-income consumers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1562–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.198549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Research Council. Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson C, Haushalter A, Buck T, Campbell D, Henderson T, Schlundt D. Development of a community-sensitive strategy to increase availability of fresh fruits and vegetables in Nashville’s urban food deserts, 2010–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E125. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) fns.usda.gov/snap/

- 47.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. The food assistance landscape: FY 2011 annual report. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2012. www.ers.usda.gov/media/376910/eib93_1_.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grimm KA, Foltz JL, Blanck HM, Scanlon KS. Household income disparities in fruit and vegetable consumption by state and territory: results of the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):2014–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman S. Low economic status is associated with suboptimal intakes of nutritious foods by adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Nutr Res. 2007;27(9):515–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorson BA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Taylor CA. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intakes in U.S. children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(3):474–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi AA, Jenks E. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):98–105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CDC. Vital signs: obesity among low-income, preschool-aged children-U.S 2008–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2013;62(31):629–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu FB. Obesity epidemiology. 1. New York NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang CY, Hsiao A, Tracy Orleans C, Gortmaker SL. The caloric calculator: average caloric impact of childhood obesity interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):e3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashe M, Graff S, Spector C. Changing places: policies to make a healthy choice the easy choice. Public Health. 2011;125(12):889–95. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]