Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Our aims were to identify and characterize the glottal response to esophageal mechanostimulation in human infants. We tested the hypotheses that glottal response is related to the type of esophageal peristaltic response, stimulus volume, and respiratory phase.

METHODS

Ten infants (2.8 kg, SD 0.5) were studied at 39.2 wk (SD 2.4). Esophageal manometry concurrent with ultrasonography of the glottis (USG) was performed. The sensory-motor characteristics of mechanostimulation-induced esophago-glottal closure reflex (EGCR, adduction of glottal folds upon esophageal provocation) were identified. Mid-esophageal infusions of air (N 41) were given and the temporal relationships of glottal response with deglutition, secondary peristalsis (SP), and the respiratory phase were analyzed using multinomial logistic regression models.

RESULTS

The frequency occurrence of EGCR (83%) was compared (P < 0.001) with deglutition (44%), SP (34%), and no esophageal responses (22%). The odds ratios (OR, 95% CI) for the coexistence of EGCR with SP (0.4, 0.06–2.2), deglutition (1.9, 0.1–26), and no response (1.9, 0.4–9.0) were similar. The response time for esophageal reflexes was 3.8 (SD 1.8) s, and for EGCR was 0.4 (SD 0.3) s (P < 0.001). Volume-response relationship was noted (1 mL vs 2 mL, P < 0.05). EGCR was noted in both respiratory phases; however, EGCR response time was faster during expiration (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of EGCR is independent of the peristaltic reflexes or the respiratory phase of infusion. The independent existence of EGCR suggests a hypervigilant state of the glottis to prevent retrograde aspiration during GER events.

BACKGROUND

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a serious challenge across the age spectrum. The causal role or association of GER with infant morbidity including dysphagia, chronic lung disease of infancy, and apparent life-threatening events is not well understood (1–3). During GER events, esophageal distention and airway symptoms can occur together. The underlying mechanism of airway symptoms caused by GER is not known in health or disease in human infants. Therefore, defining the relationship between esophageal provocations and resulting airway responses in healthy infants is a prerequisite to understanding abnormality.

Studies from human adults (4–9) and infants (10–12) have characterized the basal mechanisms and adaptive reflex in teractions within the esophagus using esophageal manometry and provocation methods. Such responses include the barrier functions of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) and lower esophageal sphincter (LES), or clearance mechanisms with secondary peristalsis (SP) and deglutition sequences. Furthermore, the glottal interactions resulting from esophageal provocation have been characterized using fluoroscopy or invasive endoscopic methods to visualize the laryngeal adduction concurrent with esophageal manometry in human adults (4, 5) and animal models (13). Use of similar methods in the assessment of glottal responses in infants is not realistic in the states of health or GER disease (GERD). The methods used in previous studies (5) require placement of the endoscope via the transnasal route, positioning the endo-scope above the glottis, and the use of local anesthetic agents. Such procedures are expensive and not feasible for prolonged esophageal-glottal assessment in infants.

Endoscopy methods may stimulate a broader sensory field, and responses are difficult to interpret in infants. Furthermore, use of endoscopic techniques might not be practical owing to increased predilection to apparent life-threatening events, gagging, choking, and obstructive apneas, which are common in infants at risk (chronic lung disease, vocal cord paralysis, or neurological impairment). Whether any of these symptoms is related to esophageal provocation is unclear. Therefore, we developed and validated a noninvasive cribside approach to evaluate glottal motion using ultrasonography of the glottis (USG) during concurrent nasolaryngoscopy in infants (14). Application of the concurrent USG with esophageal provocation may therefore be feasible to evaluate the glottal response upon esophageal stimulation in human infants (15).

Recently, using esophageal manometry and provocation techniques, we have validated and clarified the nature of esophageal peristaltic reflexes and UES contractile responses evoked upon esophageal distention in healthy infants (10, 16). By applying a specific stimulus at a targeted esophageal locus, evaluation of the glottal response may then be possible during concurrent esophageal manometry and USG.

The aims of the current study were to identify and characterize the glottal response to abrupt esophageal mechanostimulation in healthy human infants. We tested the hypotheses that upon esophageal provocation, the glottal response is related to the: (a) type of esophageal peristaltic response, (b) stimulus volume, and (c) respiratory phase. We investigated this hypothesis by analyzing the characteristics of esophageal peristaltic reflexes concurrent with glottal motion characteristics during concurrent esophageal manometry and USG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We studied 10 healthy orally fed neonates (6 male, 4 female, 25–36 wk gestation at birth, and 35–43 wk corrected gestation at evaluation). Approval was obtained from Columbus Children's Research Institute/Columbus Children's Hospital Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to study, and IRB and HIPAA compliance were followed.

Esophageal Manometry

Subjects underwent esophageal manometry as described by us before (10, 12, 16). Briefly, a specially designed esophageal manometry catheter (Dentsleeve/Mui Scientific, Mississauga, Canada) was passed nasally without using sedation or anesthesia. The catheter consisted of a UES sleeve to identify UES positioning, 5 side ports to record luminal pressure changes, and a mid-esophageal infusion port to infuse air stimuli. The catheter assembly was connected to the pneumo-hydraulic micromanometric water perfusion system via the resistors (Mui Scientific) and pressure transducers (TNF-R, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and amplifiers (UPS 2020, MMS, Dover, NH). All studies were done in the supine position, with the transducers at the level of the subject’s esophagus (mid-axillary line). Thoracic and abdominal respiratory movements were recorded with respiratory inductance plethysmography (Respitrace, Viasys, Conshohocken, PA). Vital signs were also recorded concurrently to document subject safety.

Concurrent Ultrasonography (USG)

USG was performed as described by us before (14). In this study, USG was performed concurrent with manometry using a Siemens Acuson Sequoia 512 ultrasound system (Mountain View, CA) equipped with a 15–18 MHz linear array transducer (operating between 12 MHz and 14 MHz). The ultrasound transducer was placed on the anterior neck, using gel as an acoustic coupling medium (Fig. 1). The sonographic plane during the study was maintained by direct observation on the ultrasound system. The video output signals (30 Hz) derived from USG were integrated and synchronized in real time with manometry signals using the Meteor 2 video card (MMS, Dover, NH). This technique allowed analysis of USG images, frame by frame, with concurrent manometry tracing, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Methods to elicit esophago-glottal interactions. A manometry catheter with ports in the pharynx, proximal esophagus, middle esophagus, and distal esophagus is shown. An ultrasound (USG) transducer was placed on the anterior aspect of the neck such that the vocal folds were visualized in real time. The stimulus was infused via the mid-esophageal infusion port, and the esophageal-glottal interactions were characterized.

Figure 2.

Esophago-glottal closure reflex. Effects of esophageal stimulus (1 mL air) on glottal motion are shown. Inset represents the infusion signal given via the mid-esophageal manometry port, respiration recorded with respiratory inductance plethysmography, and ultrasound images of the glottis. Magnified images of infusion signal (arrow) concurrent with ultrasound (USG) image frames are shown. The duration of infusion with a time line is shown in milliseconds. The sequence of USG images of the glottis from abduction to complete adduction and back to abduction is shown. Note the occurrence of complete glottal adduction in USG frames IV and V upon esophageal stimulation. The measurement of the sequential time interval during EGCR for the onset of complete glottal adduction (response time, hashed cone) and the duration of complete adduction (total glottal closure) are also shown.

Experimental Protocols

Studies were performed in healthy infants that were progressing with oral feedings and were not on any respiratory stimulants, neuroactive agents, prokinetics, or acid-suppressive medications. This protocol examined aerodigestive reflexes; hence, the PI and the nurse monitored the infant carefully to ensure subject protection.

After infants were allowed to adapt to the catheter systems, air stimuli were injected abruptly via the mid-esophageal infusion port (Fig. 1) during a period of esophageal manometric quiescence to determine the threshold volume to elicit esophageal reflexes as described (10).

Subsequently, USG was performed concurrent to esophageal manometry (Fig. 1). USG images and manometric signals were acquired and integrated in real time by the MMS motility system, concurrent with respiratory inductance plethysmography. During a period of esophageal quiescence, air was infused abruptly and the glottal motion charac teristics (14) and esophageal peristaltic reflex characteristics were evaluated (10, 12).

Because the main objective of this study is to evaluate the glottal responses in relation to esophageal responses, supra-threshold infusion volumes (1 mL and 2 mL) were chosen to ensure higher success rates and better consistency with esophageal responses. The order of infusions was: 1 mL infusions first, followed by 2 mL infusions. This was predefined. However, the infusions were given randomly with respect to the respiratory phase, as the investigator giving the infusion had no control of the respiratory pattern of the infant. The timing of infusion administration was predefined as follows: (a) infusions were given during a period of manometric pharyngeal and esophageal quiescence, (b) esophageal clearance must have ensued from the previous stimulus, and (c) infusions were given during a period of quiet breathing.

The above approach was used to ensure absence of residual effects of stimulus and prevent the impact of ongoing waveform suppression at proximal and distal esophageal loci. Administration of the stimulus was documented via the manometric signal (Fig. 2). All studies were performed at the cribside in the nursery.

Data Analysis

The deglutition response upon esophageal stimulation was defined as the pharyngeal waveform associated with UES relaxation and propagation into the proximal, middle, and distal esophageal segments. The onset of the pharyngeal waveform peak from the stimulus onset defines the response latency for the deglutition response.

SP is defined as the propagation of waveforms into the proximal, middle, and distal esophageal segments in the absence of pharyngeal waveform and UES relaxation. The onset of proximal esophageal upstroke from the stimulus onset defines the response latency for SP.

Frame-by-frame analysis was done to identify the characteristics of glottal closure (Fig. 2). Data analyzed manually by three observers (SRJ, AG, and BC) were as follows. First, the presence or absence of glottal adduction was documented. Second, duration in milliseconds for (a) onset of glottal adduction (EGCR response time), (b) glottal adduction onset to complete adduction, and (c) the duration of complete glottal adduction were calculated (from the onset of complete adduction to the onset of glottal abduction). Third, response times for the esophageal reflexes in seconds (SP or deglutition) were measured. Lastly, the respiratory phase in which infusion was given and the respiratory phase of the onset of glottal adduction were evaluated. Comparisons were also made between the 1.0 mL and 2.0 mL volumes.

Statistical Analysis

The data for this study consisted of several measurements per subject. The frequency of peristaltic response to stimulus was divided into three categories: SP or deglutition or none. Multinomial logistic regression models with a cluster variable for subject were used to analyze the relationship between the frequency of peristaltic infusion and the variables (EGCR response time and EGCR closure time). These models take into account the correlation in observations within the subject.

Univariate logistic regression with subject as a cluster variable was used to analyze the relationships between the binary outcome variable (presence/absence of EGCR) and each of the esophageal peristaltic response variables. The same model was used to analyze the relationship between the EGCR and each of the continuous variables (peristaltic response time, stimulus volume, and respiratory phase during stimulus). Similar analyses were again performed for the respiratory phase (inspiration or expiration) during glottal closure with each of the predictors listed above.

Mixed models with a random effect for subject were used to study the relationships between all the continuous outcome variables (peristaltic response time, EGCR response time, and EGCR closure time) and stimulus volumes and also respiratory phase during infusion. STATA (version 9, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used to perform the analyses. Means (SD = standard deviations) are reported, unless stated otherwise; P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Using the 41 stimuli as sampling units, a study would have more than 95% power to detect any of the differences in mean response time observed in this study. In addition, there would be 94% power to detect the smallest difference in proportions observed in this study (0.85–0.44).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Infants (N = 10) were of appropriate growth for gestation at birth: weight 1.3 (0.7) kg, length 35.8 (5.4) cm, head circumference 25.8 (3.4) cm. The median APGAR scores were 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. At evaluation, the cohort was normally distributed with respect to the corrected gestational age (mean 39.2 wk, SD 2.4 wk, median 39 wk, range 35–45 wk) and had age-appropriate growth parameters (mean weight 2.8 kg, SD 0.5 kg; mean length 46 cm, SD 2 cm; and mean head circumference 34 cm, SD 2 cm). At evaluation, all subjects were healthy and physiologically stable and were transitioning to oral feeds. At discharge, all subjects were safely receiving feeds via the oral route.

Clinical Observations During Concurrent Esophageal Manometry and USG of Glottis

Concurrent recordings were performed over a period of up to 15–20 minutes per subject. Infants tolerated the concurrent procedure without any discomfort. The glottal motion was observed during inspiration and expiration with reference to respiratory inductance plethysmography. Complete glottal adduction was not observed during esophageal quiescence or during normal breathing. However, during esophageal provocations, complete glottal adduction was noted, and the characteristics are further described below.

Relationship Between Esophageal Responses and Glottal Closure

Glottal adduction upon esophageal provocation was recognized: the EGCR occurred with 34 of 41 air stimuli (83% responses). During these stimuli, deglutition occurred in 18 (44%), SP in 14 (34%), and no esophageal response in 9 (22%) stimulations. The relationship between the presence or absence of SP and the presence or absence of EGCR was similar (Fisher exact test, nonsignificant). Similarly, the relationship between the presence or absence of deglutition and the presence or absence of EGCR was similar (Fisher exact test, nonsignificant). Therefore, we can assume that the occurrence of reflexes is independent.

We also evaluated the relationship between deglutition, SP, or absence of esophageal response and glottal closure using logistic regression methods. The odds ratios (OR, 95% CI) for the occurrence of SP with EGCR (0.4, 0.06–2.2), deglutition with EGCR (1.9, 0.1–26), and the absence of esophageal response with EGCR (1.9, 0.4–9.0) were statistically nonsignificant. Therefore, we can assume that the occurrence of reflexes is independent.

Next, we analyzed the response time of EGCR with the response latency for the occurrence of SP or deglutition or lack thereof (Table 1). The response times for the occurrence of EGCR with either SP or deglutition were 11-fold faster than the peristaltic reflexes (P < 0.001), thus suggesting existence of different reflex pathways for peristaltic reflexes and EGCR.

Table 1.

Response Acuity of Peristaltic Reflexes and EGCR

| Esophageal Response | Peristaltic Reflex Response Latency, Seconds | EGCR Response Latency, Seconds | Complete Glottal Closure, Seconds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary peristalsis | 3.72 (1.34) | 0.355 (0.230)* | 0.400 (0.279) |

| Deglutition | 3.84 (2.20) | 0.345 (0.250)* | 0.234 (0.133) |

| No response | None | 0.321 (0.303) | 0.318 (0.292) |

Mean (SD)

P < 0.001 versus esophageal response latency.

Next, we analyzed the duration of complete glottal closure during esophageal responses. The glottal closure durations were similar regardless of the esophageal events (Table 1).

Relationship Between the Stimulus Volume and EGCR Response Acuity

Glottal closure response acuity or the intensity of the glottal closure response was measured by (a) the response latency to the onset of EGCR and (b) the duration of glottal closure. To test the relationship between glottal closure and infusion volume, we compared the response latency and the durations of EGCR, at 1 mL and 2 mL volumes (Fig. 3). No differences were found in the response times for EGCR between the infusion volumes tested (P > 0.05, regression analysis). However, the glottis remained completely adducted by a 2-fold duration at higher infusion volumes (P < 0.02, logistic regression).

Figure 3.

Effect of graded esophageal air stimuli on response latency and magnitude of glottal adduction. EGCR response time (gray cones) and glottal closure duration (black bars) at 1 mL and 2 mL volumes are shown. At the higher volume, the glottis takes a longer period to adduct, and remains fully adducted for a significantly longer period (P < 0.03).

At 1 mL volume, the response latency (least squares means, 95% CI) to the onset of peristaltic response (3.4 s,– to 1.1) and EGCR (0.38 s, −0.15 to 0.15) were different (P < 0.001). Also, at 2 mL volume, the response latency to the onset of peristaltic response (3.7 s, –1.2 to 1.2) and EGCR (0.43 s, –0.17 to 0.17) were different (P < 0.001).

Relationship Between the Respiratory Phase and EGCR Response Acuity

The respiratory phase during which the infusions were given was recognized, as well as the phase during which glottal adduction occurred (Figs. 2 and 4). An example of four scenarios for the occurrence of EGCR in relation to respiratory phase is described (Fig. 4). Twenty-eight infusions were given during inspiration, and 13 given during expiration.

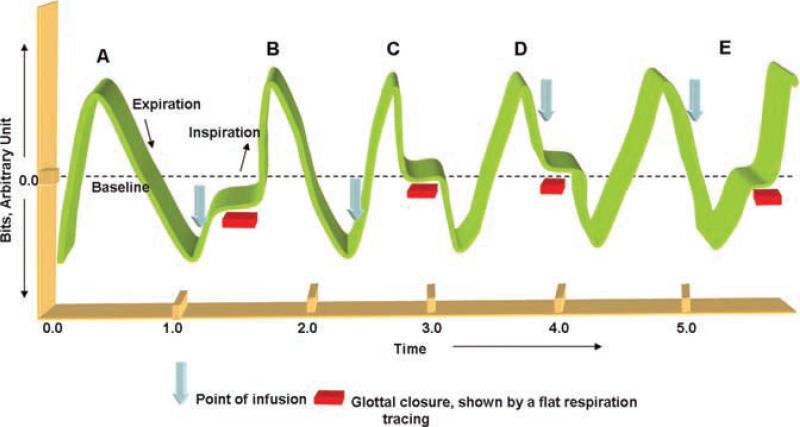

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of 4 possible scenarios (B, C, D, and E) for the occurrence of EGCR (horizontal bars) in relationship to the respiratory phase of the given infusion (arrows) is shown. All stimuli were given randomly with respect to the respiratory phase. Scenario (A) represents basal respiration seen during esophageal quiescence. In (B), infusion was given during inspiration and glottal adduction occurred in inspiration. In (C), infusion was given in inspiration and glottal adduction occurred in expiration. In (D), infusion was given in expiration and glottal adduction occurred in expiration. In (E), infusion was given in expiration and glottal adduction occurred in inspiration.

EGCR occurred 86% of the times when infusions were given during inspiration (14% absence of glottal closure). Within which, glottal adduction was noted in inspiration (71%, Fig. 4B), as well as in expiration (29%, Fig. 4C). EGCR occurred 77% of the times when infusions were given during expiration (23% absence of glottal closure). Within which, glottal adduction was noted in expiration (70%, Fig. 4D), as well as in inspiration (30%, Fig. 4E). The odds ratio of EGCR occurrence in inspiration was 5.6 times (CI 2.5–13.1, P < 0.0001) higher than in expiration, when the esophagus was provoked in inspiration.

The adjusted response latency of EGCR and duration of glottal closure in relation to the respiratory phase of esophageal provocation are described in Table 2. EGCR occurrence was quicker during expiration (P < 0.02, scenario D in Fig. 4) and was delayed during inspiration (scenario B in Fig. 4). However, the duration of glottal adduction was independent of the respiratory phase of esophageal provocation.

Table 2.

Relationship Between EGCR Response Acuity and Respiratory Phases

| Characteristics | Phase of Inspiration During Infusion | Mean (SD) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGCR response time* | Inspiration | 0.45 (0.24)* | 0.016 |

| Expiration | 0.19 (0.19) | ||

| Glottal closure time | Inspiration | 0.32 (0.22) | 0.57 |

| Expiration | 0.28 (0.26) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reveal the unique relationship between the esophagus and glottis in human infants. This is the first systematic study characterizing the EGCR using novel manometry provocation methods concurrent with noninvasive USG.

The salient features of this study are: (a) the use of USG as a noninvasive method to evaluate glottal motion during esophageal provocation at any age, (b) the recognition of glottal closure reflex upon esophageal provocation, (c) the independent existence of glottal closure reflex and esophageal peristaltic reflex responses upon provocation, (d) the different response latencies of the aerodigestive reflexes with esophageal stimulation, (e) the volume-dependent increase in glottal closure duration, and (f) the occurrence of glottal closure in both phases of respiration.

The presence of EGCR has been described in the adult human and feline models before using videoendoscopic methods concurrent with esophageal manometry (5, 13). Such methods run the risk of invasiveness and application of anesthetics, which may expand or modify the area of sensory stimulation, respectively. Hence, wider applications of those methods to study physiology or pathophysiology in health or diseases of the infant esophagus are not feasible. This report describes the techniques and methodology to characterize the interesting relationship between the glottis and esophagus that could distinguish physiologic from pathophysiologic conditions crosscutting all ages.

Glottal adduction can be protective against aspiration during swallowing or belching (17–19) or during pharyngeal or esophageal provocation (5, 20). Glottal adduction can also increase airway resistance during cough or airway hyperreactivity (21). GER events may cause supraesophageal or extraesophageal symptoms in infants (22, 23); however, the methods to describe the direct association between esophageal distention and glottal motion have not been adequate. Evaluation of glottal function using endoscopy methods in infants suffering with anterograde or retrograde aspiration can be limited to identification of gross structural pathology and vocal cord movement (24, 25).

In the current study, we have quantified the sensory-motor characteristics of EGCR. Both esophageal reflexes and glottal adduction occurred independently, as shown by the signifi-cant differences in frequency occurrence and response latency. This may suggest that these reflexes may be activated by different receptors, and the functions may be complementary. That airway closure may be a hypervigilant response is suggested by the occurrence of EGCR 10–12-fold earlier than the peristaltic reflexes.

The occurrence of peristaltic reflexes favoring esophageal clearance and preventing the entry of stimulus into the proximal aerodigestive tract can be protective during health. However, infants born prematurely or those surviving with chronic lung disease are at increased risk of dysphagia, GERD, and esophageal dysmotility. These conditions may result from failure of protective aerodigestive reflexes. Future studies are possible to evaluate the pathophysiology of EGCR in infants at risk of airway compromise. Lack of invasiveness to study glottal motion may be more acceptable to study the differences in health or disease across the age spectrum. Furthermore, this approach will minimize stress (crying in infants) during evaluation that may otherwise confound the findings.

The relationship between esophageal peristaltic response and glottal closure was examined. The odds ratios for the occurrence of EGCR with the presence or absence of peristaltic reflex were statistically nonsignificant, thus suggesting independent occurrence of these phenomena. Duration of glottal adduction increased significantly in response to an increase in the volume of air stimulus. Glottal adduction in this context may be considered an enhancement of airway protective function with greater bolus volume or esophageal distention, which may modify the afferent-efferent interactions.

During normal respiration, vocal cords move but are not closed completely to facilitate transport of air. However, upon esophageal mechanostimulation, abrupt closure of vocal cords in both phases of respiration was noted. The administration of the stimulus was random with regard to the respiratory phase. Esophageal mechanostimulation may stimulate the esophageal stretch receptors and the vagal afferents, transmitting sensory impulses to the brain stem. The efferent signals traverse in the vagus via the recurrent laryngeal and superior laryngeal nerves to the laryngeal adductor muscles. Recruitment of different esophageal afferent pathways may have activated different motor pathways: peristaltic reflexes and glottal closure reflex. The fact that EGCR occurred in either respiratory phase suggests that closure of the glottal opening took precedence over the completion of the respiratory phase.

The relationship with respiratory phases and the EGCR may also suggest an interruption of neuronal discharge to the respiratory center. When the infusion was given in inspiration, the response latency for glottal adduction was significantly prolonged compared to the infusion given during expiration. However, the glottal closure duration was similar. This may be due to several possibilities: (a) regulation of glottal adduction and glottal respiratory motion are independent, or (b) during inspiratory esophageal stimulus, the prolonged time necessary to result in glottal adduction may be needed to overcome the inspiratory neuronal discharge, during which the glottis is normally in an abducted state.

The regulation of the inspiration-expiration cycle by chemoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, and nociceptive receptors has been known in human or animal models (26–29). Glottal closure during inspiration may be protective in that esophageal luminal contents are prevented from being inhaled as in retrograde aspiration. Furthermore, glottal closure during expiration may support an exaggerated protection or hypervigilant state of the airway. Nevertheless, glottal closure increases airway resistance and alters respiratory mechanics during esophageal provocation, such as GERD (28–30). Further studies are needed to evaluate esophageal-glottal interactions in order to understand the pathophysiology of chronic lung disease of infancy.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the existence of esophageal-glottal interactions in human infants using concurrent manometry and ultrasonography of the glottis. Esophageal mechanostimulation resulted in esophageal peristaltic responses and a glottal adduction response, regardless of the phase of respiration. Thus, esophageal afferent stimulation resulted in esophageal efferent outputs recorded as peristaltic reflexes, and also glottal efferent outputs recorded as glottal adduction. It is likely that such reflexes may provide airway protection during GER events, belching, swallowing, or emesis in infants. The methods described in this article can be applicable to study esophageal-glottal interactions cross-cutting across all age spectrums.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

What Is Current Knowledge

Defining the protective role of glottal function during aspiration remains a challenge across the age spectrum.

Esophago-glottal closure reflex (EGCR) has been characterized in adults and feline models using fluoroscopy or invasive endoscopic methods.

However, such studies are not feasible in infants at risk.

What Is New Here

EGCR has been defined in neonates using novel methods at cribside concurrent esophageal manometry and ultrasonography of the glottis.

EGCR occurs upon esophageal mechanostimulation independent of peristaltic reflexes.

These methods may permit evaluation of the relationship between the esophagus and glottis safely, and may be applicable across all ages.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health RO1 DK 068158 to Sudarshan R. Jadcherla.

Footnotes

Specific author contributions: Sudarshan R. Jadcherla: principal investigator, involved with the development of methods, concept and study design, IRB process, conduct and performance of study protocol, data analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. Alankar Gupta: involved with data analysis, assistance with performance of study, and writing of this manuscript. Brian Coley involved with performance and interpretation of ultrasonography of glottis, and writing of this manuscript. Soledad Fernandez: involved with statistical design and analysis of the data, assistance with interpretation of results, and writing of this manuscript. Reza Shaker: involved with research consultation during study protocol, data interpretation, and writing of this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Sudarshan R. Jadcherla, M.D., F.R.C.P.I., D.C.H.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jadcherla SR, Rudolph CD. Gastroesophageal reflux in the preterm neonate. Neo Reviews. 2005;6:e87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orenstein SR. An overview of reflux-associated disorders in infants: Apnea, laryngospasm, and aspiration. Am J Med. 2001;111:60S–3S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00823-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:569–72. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaker R, Hogan WJ. Reflex-mediated enhancement of airway protective mechanisms. Am J Med. 2000;108(Suppl 4a):8S–14S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaker R, Dodds WJ, Ren J, et al. Esophagoglottal closure reflex: A mechanism of airway protection. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:857–61. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90169-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittal RK, Liu J. Flow across the gastro-esophageal junction: Lessons from the sleeve sensor on the nature of anti-reflux barrier. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:187–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal RK. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux: Motility factors. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(Suppl 15):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyal RK, Padmanabhan R, Sang Q. Neural circuits in swallowing and abdominal vagal afferent-mediated lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Am J Med. 2001;111:95S–105S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00863-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyal RK, Paterson WG. Esophageal motility. In: Schultz SG, editor. Handbook of physiology. Section 6: The gastrointestinal system 1. Motility and circulation, part 2. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1989. pp. 865–908. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadcherla SR, Duong HQ, Hoffmann RG, et al. Esophageal body and upper esophageal sphincter motor responses to esophageal provocation during maturation in preterm newborns. J Pediatr. 2003;143:31–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadcherla SR. Manometric evaluation of esophageal-protective reflexes in infants and children. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 3A):157S–60S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadcherla SR, Hoffmann RG, Shaker R. Effect of maturation of the magnitude of mechanosensitive and chemosensitive reflexes in the premature human esophagus. J Pediatr. 2006;149:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaker R, Ren J, Medda B, et al. Identification and characterization of the esophagoglottal closure reflex in a feline model. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G147–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.1.G147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Correlation of glottal closure using concurrent ultrasonography and nasolaryngoscopy in children: A novel approach to evaluate glottal status. Dysphagia. 2006;21:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00455-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Characterization of esophago-glottal closure reflex (EGCR) in healthy neonates using a novel non-invasive ultrasonography of glottis (USG) technique concurrent with esophageal stimulation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:A–410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Jadcherla SR. The relationship between somatic growth and in vivo esophageal segmental and sphincteric growth in human neonates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:35–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000226368.24332.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiro J, Rendell JK, Gay T. Activation and coordination patterns of the suprahyoid muscles during swallowing. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1376–82. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamir Z, Ren J, Hogan WJ, et al. Coordination of deglutitive vocal cord closure and oral-pharyngeal swallowing events in the elderly. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:425–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren J, Shaker R, Zamir Z, et al. Effect of age and bolus variables on the coordination of the glottis and upper esophageal sphincter during swallowing. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:665–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaker R, Ren J, Bardan E, et al. Pharyngoglottal closure reflex: Characterization in healthy young, elderly and dysphagic patients with predeglutitive aspiration. Gerontology. 2003;49:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000066504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canning BJ. Anatomy and neurophysiology of the cough reflex. ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:33S–47S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.33S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Serag HB, Gilger M, Kuebeler M, et al. Extra-esophageal association of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children without neurologic defects. Gastroenterology. 2001;21:1294–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClave SA, DeMeo MT, DeLegge MH, et al. North American summit on aspiration in the critically ill patient: Consensus statement. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:S80–5. doi: 10.1177/014860710202600613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman EM. Role of ultrasound in the assessment of vocal cord function in infants and children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:199–209. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susan S. Gray's anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice. 39 Ed. Churchill Livingstone; London, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tryfon S, Kontakiotis T, Mavrofridis E, et al. Hering-Breuer reflex in normal adults and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and interstitial fibrosis. Respiration. 2001;68:140–4. doi: 10.1159/000050483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta JN, Saha JK, Goyal RK. Stimulus-response function studies of esophageal mechanosensitive nociceptors in sympathetic afferents of opossum. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:796–812. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.3.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu DN, Yamauchi K, Kobayashi H, et al. Effects of esophageal acid perfusion on cough responsiveness in patients with bronchial asthma. Chest. 2002;122:505–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu DN, Tanifuji Y, Kobayashi H, et al. Effects of esophageal acid perfusion on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with bronchial asthma. Chest. 2000;118:1553–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.6.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodi U, Harding SM, Coghlan HC, et al. Autonomic regulation in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. Chest. 1997;111:65–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]