Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

β-lactam antimicrobials are the most commonly prescribed group of antimicrobials in Canada, and are categorized by the WHO as critically and highly important antimicrobials for human medicine. Because antimicrobial use is commonly associated with the development of antimicrobial resistance, monitoring the volume and patterns of use of these agents is highly important.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the use of penicillin and cephalosporin antimicrobials within Canadian provinces over the 1995 to 2010 time frame according to two metrics: prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days and the average defined daily doses dispensed per prescription.

METHODS:

Antimicrobial prescribing data were acquired from the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and the Canadian Committee for Antimicrobial Resistance, and population data were obtained from Statistics Canada. The two measures developed were used to produce linear mixed models to assess differences among provinces and over time for the broad-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporin groups, while accounting for repeated measurements at the provincial level.

RESULTS:

Significant differences among provinces were found, as well as significant changes in use over time. A >28% reduction in broad-spectrum penicillin prescribing occurred in each province from 1995 to 2010, and a >18% reduction in cephalosporin prescribing occurred in all provinces from 1995 to 2010, with the exception of Manitoba, where cephalosporin prescribing increased by 18%.

DISCUSSION:

Significant reductions in the use of these important drugs were observed across Canada from 1995 to 2010. Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec emerged as divergent from the remaining provinces, with high and low use, respectively.

Keywords: Antimicrobial use, β-lactam, Broad-spectrum penicillin, Cephalosporin, Penicillin, Provincial variation, Surveillance

Abstract

INTRODUCTION :

Les β-lactamines représentent le groupe d’antimicrobiens le plus prescrit au Canada et, d’après l’OMS, elles revêtent une importance capitale en médecine humaine. Puisque l’utilisation d’antimicrobiens s’associe souvent au développement d’une résistance antimicrobienne, il est essentiel de surveiller le volume et les modes d’utilisation de ces agents.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer l’utilisation de pénicilline et de céphalosporines au sein des provinces canadiennes entre 1995 et 2010 selon deux mesures : les prescriptions par 1 000 habitants-jours et les doses théra-peutiques quotidiennes moyennes dispensées par prescription.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont extrait les données sur la prescription d’antimicrobiens du Programme intégré canadien de surveillance de la résistance aux antimicrobiens et du Comité canadien sur la résistance aux antibiotiques, et les données en population de Statistique Canada. À l’aide des deux mesures élaborées, ils ont produit des modèles linéaires mixtes pour évaluer les différences entre les provinces et dans le temps dans les groupes de pénicilline à large spectre et de céphalosporines, tout en tenant compte des mesures répétées sur la scène provinciale.

RÉSULTATS :

Les chercheurs ont constaté des différences significatives entre les provinces, ainsi que des changements importants d’utilisation dans le temps. Les prescriptions de pénicilline à large spectre ont diminué de plus de 28 % dans chaque province entre 1995 et 2010, et celles de céphalosporines ont reculé de plus de 18 % dans toutes les provinces entre 1995 et 2010, à l’exception du Manitoba, où les prescriptions de céphalosporines ont augmenté de 18 %.

EXPOSÉ :

Les chercheurs ont observé d’importantes réductions dans l’utilisation de ces médicaments au Canada entre 1995 et 2010. Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador et le Québec divergeaient des autres provinces, avec un usage élevé et faible, respectivement.

It is known that antimicrobial use in Canada varies according to province and antimicrobial class (1,2). However, to the best of our knowledge, provincial patterns of use at the class or individual drug level have not been critically analyzed in the literature to date. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to detail trends in class and drug level use of the major classes of β-lactam antimicrobial agents, the penicillins and cephalosporins, in Canada over a 15-year time period. A secondary objective was to compare the use of these classes in 2010 with use rates reported by European Union (EU) countries through the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Network (ESAC-Net) (3–5). Trends were assessed using two measures of antimicrobial consumption: prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrID), which is a population- and time-adjusted measure of the volume of prescriptions acquired by the outpatient population, and the average defined daily doses (DDDs) dispensed per prescription, which is a measure of the volume of active ingredient dispensed per prescription, reflecting the strength of the dispensed product and the length of therapy.

METHODS

Antimicrobial prescribing and extended unit data for all individual penicillin and cephalosporin antimicrobials dispensed in Canadian provinces from 2000 to 2010 were collected by IMS Health Canada, and acquired from the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance (6). In addition, supplemental data for the total amount of broad-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporin prescribing were acquired from the Canadian Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance, which was active until 2009 (7). The four agents included within the broad-spectrum penicillin grouping were amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, carbenicillin and pivampicillin. These supplemental data spanned from 1995 to 1999. The Canadian CompuScript dataset is developed by accessing all marketed outpatient drug data dispensed via prescriptions by 5900 geographically representative retail pharmacies across Canada, with provincial-level coverage ranging from 51% to 88%. Geospatial extrapolation is used to infer use across all 8800 pharmacies (current to May 2013). The extrapolation stratifies according to pharmacy size, type and province (8). This methodology nullifies any variance in store coverage over time and across geography. All data were reported monthly according to province for all new and refilled prescriptions. The Canadian CompuScript dataset included individual drug-level prescription count information, but also included manufacturer name, extended units prescribed (total number of tablets, capsules, millilitres, etc), drug strength, volume of active ingredient and patient acquisition cost. Data from Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island were combined for the years 1999 to 2004. In 2005 and subsequent years, data from these provinces were provided individually. Population values were acquired from Statistics Canada (9). Where necessary, prescribing data were merged and, together with population data, were used to produce PrID, DDD per prescription and DDDs per 1000 inhabitant-days (DID) measures.

Linear mixed models were built in a forward stepwise fashion to describe provincial differences in broad-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporin group prescribing and average DDDs per prescription over time. Province, year, and appropriate quadratic and interaction terms were assessed as predictors for use at P<0.05 and assessed for confounding effects using a 25% change cut-off in any significant coefficient. Quadratic terms for year were assessed at P<0.05 where visually appropriate to model a curvilinear relationship between time and the outcome, as well as interaction terms between province and year, and province with the quadratic term for year. Repeated measures were accounted for by assigning a first-order autoregressive correlation structure, and the natural logarithm transformation was applied to the outcome variable to meet the assumption of homoscedasticity where required. Normality was assessed and met, and residual analyses performed to highlight outlying observations. Data for any outlying observations were assessed to assure that recording errors were not present; however, models were built using all observations to limit any potential bias.

European antimicrobial use data from 2009 were acquired from ESAC-Net, and rankings performed such that country with lowest use was assigned a rank of 1. Comparisons were made using three measurements: DIDs, PrIDs and DDDs per prescription. All calculations and analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, USA) for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, USA) and graphs were produced in Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

Nineteen β-lactam antimicrobials were used in outpatient antimicrobial therapy by Canadian prescribers between 1995 and 2010. Twelve belonged to the penicillin class (amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, ampicillin, bacampicillin, cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin, oxacillin, penicillin G, penicillin V, pivampicillin and pivmecillinam) and seven to the cephalosporin class (cefaclor, cefadroxil, cefixime, cefprozil, cefuroxime axetil, cephalexin and cephra-dine). Eight antimicrobials represented 91% to >98% of total β-lactam use over the study time frame: amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, cefixime, cefprozil, cefuroxime axetil, cephalexin, cloxacillin and penicillin V.

Broad-spectrum penicillin models

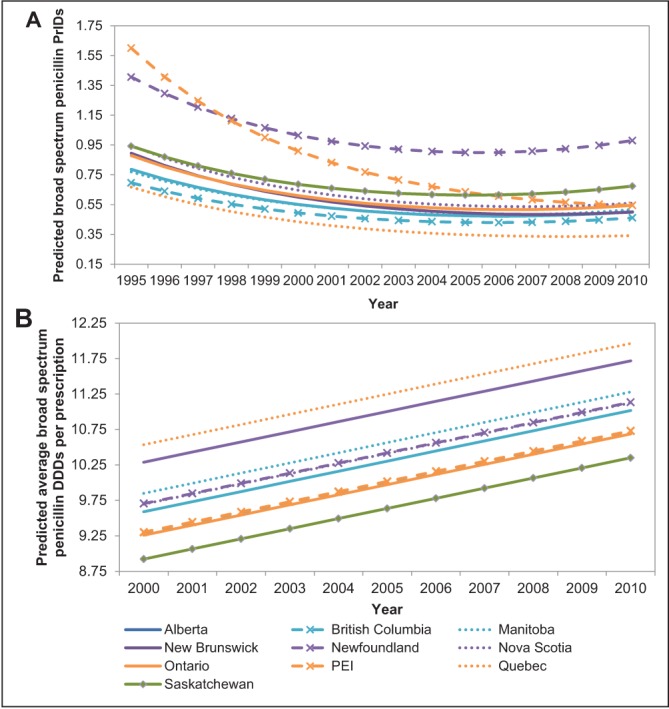

The pattern of broad-spectrum penicillin prescribing were similar among many of the provinces over time, with a decline occurring from 1995 to 2004, followed by a plateau or slight increase by 2010 (Figure 1A). A modest increase during the latter portion of the analysis period occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan from 2006 onward (Figure 1A). Quebec was found to have significantly lower broad-spectrum prescribing rates over the entire time frame compared with all other provinces (P<0.05). In contrast, Newfoundland and Labrador was found to have significantly higher broad-spectrum penicillin prescribing rates from 2001 to 2010 compared with the remaining provinces (P<0.05). For 2010 data, all pairwise combinations of provinces were assessed for significant differences in their prescribing rates. The P values for these comparisons are presented in Table 1 for use in combination with Figure 1A.

Figure 1).

Linear mixed-model predicted values for the trends in the prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrIDs) (A) and daily defined doses (DDDs) (B) for broad-spectrum penicillin antimicrobials in Canada, according to province, 1995 to 2010. PEI Prince Edward Island

TABLE 1.

P values for the difference in all pairwise combinations of provinces in 2010 for the linear mixed model describing provincial prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days for broad-spectrum penicillin antimicrobials in Canada, 1995 to 2010

| BC | MB | NB | NF | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | ns | ns | ns | <0.001 | 0.017 | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BC | – | 0.01 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MB | – | – | ns | <0.001 | ns | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NB | – | – | – | <0.001 | 0.012 | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NF | – | – | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NS | – | – | – | – | – | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ON | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| QC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | <0.001 |

This table is a companion table to Figure 1A. BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NF Newfoundland and Labrador; ns No significant difference in the prescribing rates between the two provinces; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; PE Prince Edward Island; QC Quebec; SK Saskatchewan

A pattern of increasing average broad-spectrum penicillin DDDs per prescription was apparent for all of the provinces (Figure 1B). In contrast to the PrID model, Quebec had significantly higher DDDs per prescription than all provinces with the exception of New Brunswick (P<0.05). Saskatchewan displayed the lowest DDDs per prescription, significantly lower than all provinces except Ontario (P<0.05). All pairwise combinations of provinces were assessed for significant differences in their prescribing rates. The P values for these comparisons are presented in Table 2 for use in combination with Figure 1B.

TABLE 2.

P values for the difference in all pairwise combinations of provinces for the linear mixed model describing provincial defined daily doses (DDDs) per prescription for broad-spectrum penicillin antimicrobials in Canada, 1995 to 2010

| BC | MB | NB | NF | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | ns | ns | <0.001 | ns | ns | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BC | – | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.022 | 0.024 | ns | ns | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| MB | – | – | 0.013 | ns | ns | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NB | – | – | – | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 |

| NF | – | – | – | – | 0.012 | ns | 0.023 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NS | – | – | – | – | – | 0.013 | 0.026 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ON | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| PE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | <0.001 | 0.031 |

| QC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | <0.001 |

This table is a companion table to Figure 2A. BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NF Newfoundland and Labrador; ns No significant difference in the DDDs per prescription between the two provinces; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; PE Prince Edward Island; QC Quebec; SK Saskatchewan

Cephalosporin models

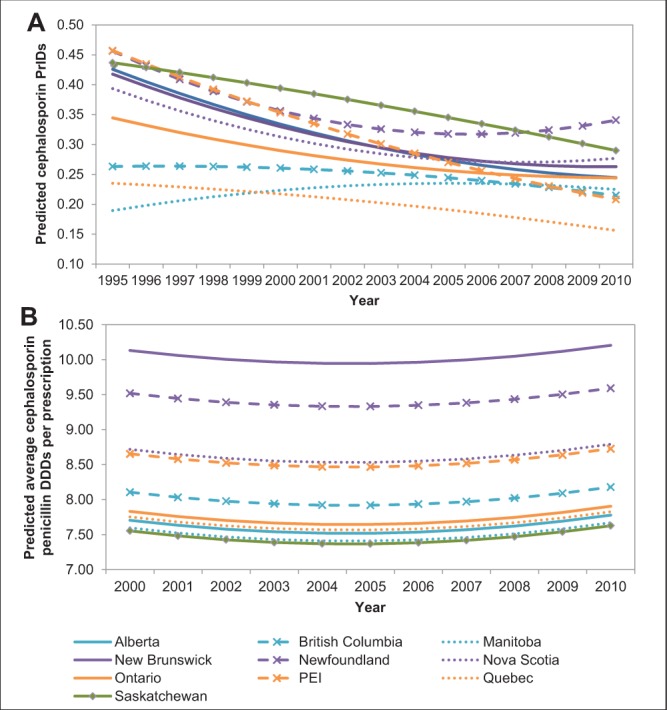

Variable patterns in the use of cephalosporins were apparent among the provinces (Figure 2A). The most divergent provinces were Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec. Newfoundland and Labrador exhibited increasing rates of use between 2005 and 2010, whereas the remaining provinces displayed a plateau or reductions in prescribing over this time period (P<0.05). In contrast, cephalosporin prescribing in Quebec was reduced from year to year, and was significantly lower than all other provinces between 2004 and 2010 (P<0.05; Figure 2A). For 2010 data, all pairwise combinations of provinces were assessed for significant differences in their prescribing rates. The P values for these comparisons are presented in Table 3 for use in combination with Figure 2A.

Figure 2).

Linear mixed-model predicted values for the trends in the prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrIDs) (A) and daily defined doses (DDDs) (B) for cephalosporin antimicrobials in Canada, according to province, 1995 to 2010. PEI Prince Edward Island

TABLE 3.

P values for the difference in all pairwise combinations of provinces in 2010 for the linear mixed model describing provincial prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days for cephalosporin antimicrobials in Canada, 1995 to 2010

| BC | MB | NB | NF | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | ns | ns | ns | <0.001 | ns | ns | ns | 0.001 | ns |

| BC | – | ns | ns | <0.001 | 0.019 | ns | ns | 0.026 | 0.005 |

| MB | – | – | ns | <0.001 | 0.048 | ns | ns | 0.010 | 0.014 |

| NB | – | – | – | 0.004 | ns | ns | 0.038 | <0.001 | ns |

| NF | – | – | – | – | 0.016 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns |

| NS | – | – | – | – | – | ns | 0.010 | <0.001 | ns |

| ON | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns | 0.001 | ns |

| PE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.049 | 0.002 |

| QC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | <0.001 |

This table is a companion table to Figure 2A. BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NF Newfoundland and Labrador; ns No significant difference in the prescribing rates between the two provinces; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; PE Prince Edward Island; QC Quebec; SK Saskatchewan

A pattern of gradual decreasing cephalosporin DDDs per prescription occurred from 2000 to 2004, followed by a slight increase from 2005 to 2010 (Figure 2B). Significant differences among the provinces were uncommon; all significant comparisons included New Brunswick or Newfoundland and Labrador. New Brunswick DDDs per prescription were significantly higher than all provinces with the exception of Newfoundland and Labrador, and Newfoundland and Labrador DDDs per prescription were significantly higher than Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Quebec and Ontario (P<0.05). All pairwise combinations of provinces were assessed for significant differences in their prescribing rates. The P values for these comparisons are presented in Table 4 for use in combination with Figure 2B.

TABLE 4.

P values for the difference in all pairwise combinations of provinces for the linear mixed model describing provincial defined daily doses per prescription for cephalosporin antimicrobials in Canada, 1995 to 2010

| BC | MB | NB | NF | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | ns | ns | 0.003 | 0.026 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| BC | – | ns | 0.013 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| MB | – | – | 0.002 | 0.019 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| NB | – | – | – | ns | ns | 0.005 | ns | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| NF | – | – | – | – | ns | 0.038 | ns | 0.031 | 0.016 |

| NS | – | – | – | – | – | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| ON | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns | ns | ns |

| PE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns | ns |

| QC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ns |

This table is a companion table to Figure 2B. BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NF Newfoundland and Labrador; ns No significant difference in the prescribing rates between the two provinces; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; PE Prince Edward Island; QC Quebec; SK Saskatchewan

Drug-level comparison of use in Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec

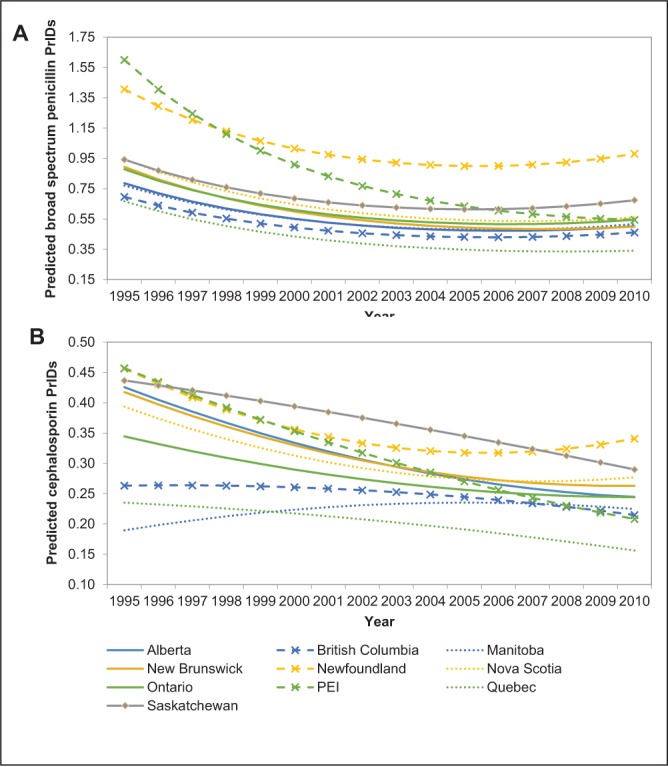

The raw PrID data from Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec were examined at the level of the individual drug (Figure 3A and 3B). Penicillin prescribing in Newfoundland and Labrador was driven by amoxicillin and was considerably higher than that observed in Quebec (approximately 0.9 PrIDs in Newfoundland and Labrador and 0.3 PrIDs in Quebec). Similarly, the prescribing of cephalosporins in Newfoundland and Labrador was driven by a single drug: cephalexin, at a rate of approximately five times that of the cephalexin prescribing reported in Quebec. Interestingly, the most commonly prescribed cephalosporin in Quebec was different from that in Newfoundland and Labrador; in Quebec, the yearly PrIDs for cefprozil ranged from 0.07 to 0.10, while cefprozil was very rarely prescribed in Newfoundland and Labrador between 2000 and 2010.

Figure 3).

Raw individual drug-level prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrIDs) for all broad-spectrum penicillin (A) and cephalosporin (B) antimicrobials dispensed in Canada, according to province, 2000 to 2010. PEI Prince Edward Island

Comparison with reporting EU countries

National and provincial-level PrIDs, DIDs and average DDDs per prescription for the year 2009 were compared with countries from the EU, as reported by ESAC-Net (3–5). Comparisons for penicillin and cephalosporin use are presented in Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of total broad-spectrum penicillin use among Canada and the reporting European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Network countries according to defined daily doses (DDDs) per 1000 inhabitant-days (DIDs), prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrIDs) and DDD per prescription measures in 2009

|

DID

|

PrID

|

DDD per prescription

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country or province | Value | Rank | Value | Rank | Value | Rank |

| Alberta | 6.27 | 11 | 0.64 | 6 | 9.84 | 16 |

| Austria | 7.09 | 18 | 0.68 | 11 | 10.43 | 22 |

| Belgium | 15.13 | 40 | 1.25 | 24 | 12.07 | 28 |

| British Columbia | 5.41 | 8 | 0.56 | 2 | 9.69 | 13 |

| Bulgaria | 8.40 | 24 | 0.98 | 17 | 8.60 | 8 |

| Canada | 5.97 | 9 | 0.60 | 4 | 9.93 | 18 |

| Croatia | 9.69 | 28 | 1.05 | 18 | 9.19 | 12 |

| Cyprus | 16.01 | 42 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Czech Republic* | 7.73 | 21 | 0.69 | 12 | 11.13 | 27 |

| Denmark | 10.00 | 29 | 1.13 | 21 | 8.86 | 10 |

| Estonia | 4.37 | 4 | 0.65 | 9 | 6.70 | 3 |

| Finland | 6.14 | 10 | 0.74 | 15 | 8.34 | 7 |

| France | 16.08 | 43 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Germany | 4.27 | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Greece | 12.89 | 38 | 1.47 | 27 | 8.77 | 9 |

| Hungary | 7.06 | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Iceland | 10.41 | 31 | 1.33 | 26 | 7.83 | 5 |

| Ireland* | 10.66 | 32 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Israel | 11.82 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Italy† | 15.18 | 41 | 3.40 | 28 | 4.46 | 2 |

| Latvia | 4.80 | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lithuania | 10.08 | 30 | 1.11 | 20 | 9.08 | 11 |

| Luxembourg | 13.47 | 39 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Malta | 9.08 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Manitoba | 7.31 | 20 | 0.73 | 13 | 10.03 | 19 |

| New Brunswick | 6.66 | 15 | 0.62 | 5 | 10.66 | 25 |

| Newfoundland | 11.88 | 35 | 1.13 | 22 | 10.50 | 23 |

| Norway | 6.59 | 14 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nova Scotia | 6.51 | 13 | 0.64 | 7 | 10.19 | 20 |

| Ontario | 6.37 | 12 | 0.65 | 8 | 9.80 | 15 |

| Prince Edward Island | 7.25 | 19 | 0.73 | 14 | 9.91 | 17 |

| Poland | 10.68 | 33 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Portugal | 12.00 | 36 | 1.11 | 19 | 10.84 | 26 |

| Quebec | 4.54 | 6 | 0.44 | 1 | 10.26 | 21 |

| Romania | 4.31 | 3 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Russian Federation | 4.23 | 1 | 1.29 | 25 | 3.28 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 8.37 | 23 | 0.86 | 16 | 9.74 | 14 |

| Slovakia | 9.56 | 27 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Slovenia | 9.51 | 26 | 1.24 | 23 | 7.67 | 4 |

| Spain | 12.31 | 37 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sweden | 6.98 | 16 | 0.66 | 10 | 10.58 | 24 |

| The Netherlands | 4.48 | 5 | 0.57 | 3 | 7.86 | 6 |

| United Kingdom | 8.03 | 22 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Lowest use ranking = 1. NR Not reported,

2008 values,

2007 values

TABLE 6.

Comparison of total cephalosporin use among Canada and the reporting European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Network countries according to defined daily doses (DDDs) per 1000 inhabitant-days (DIDs), prescriptions per 1000 inhabitant-days (PrIDs) and DDD per prescription measures in 2009

|

DID

|

PrID

|

DDDs per prescription

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country or province | Value | Rank | Value | Rank | Value | Rank |

| Alberta | 1.90 | 21 | 0.25 | 13 | 7.76 | 19 |

| Austria | 1.80 | 17 | 0.31 | 19 | 5.82 | 11 |

| Belgium | 1.82 | 18 | 0.14 | 5 | 12.58 | 28 |

| British Columbia | 1.86 | 20 | 0.22 | 9 | 8.26 | 22 |

| Bulgaria | 2.30 | 26 | 0.51 | 23 | 4.49 | 5 |

| Canada | 1.84 | 19 | 0.23 | 11 | 7.95 | 21 |

| Croatia | 3.70 | 37 | 0.60 | 24 | 6.21 | 13 |

| Cyprus | 6.45 | 42 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Czech Republic* | 1.55 | 14 | 0.18 | 7 | 8.52 | 24 |

| Denmark | 0.03 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 5.73 | 10 |

| Estonia | 0.83 | 10 | 0.18 | 8 | 4.49 | 6 |

| Finland | 2.33 | 27 | 0.41 | 22 | 5.71 | 9 |

| France | 2.92 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Germany | 2.39 | 29 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Greece | 8.68 | 43 | 1.49 | 27 | 5.82 | 12 |

| Hungary | 1.98 | 24 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Iceland | 0.30 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ireland* | 1.33 | 13 | 0.39 | 21 | 3.37 | 4 |

| Israel | 3.96 | 38 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Italy† | 2.78 | 32 | 3.18 | 28 | 0.87 | 2 |

| Latvia | 0.43 | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lithuania | 1.27 | 12 | 0.66 | 25 | 1.90 | 3 |

| Luxembourg | 4.33 | 40 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Malta | 5.50 | 41 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Manitoba | 1.76 | 16 | 0.23 | 10 | 7.74 | 18 |

| New Brunswick | 2.97 | 35 | 0.28 | 16 | 10.77 | 27 |

| Newfoundland | 3.32 | 36 | 0.33 | 20 | 10.01 | 26 |

| Norway | 0.13 | 3 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nova Scotia | 2.46 | 30 | 0.27 | 15 | 8.99 | 25 |

| Ontario | 1.99 | 25 | 0.25 | 14 | 7.82 | 20 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.93 | 22 | 0.23 | 12 | 8.27 | 23 |

| Poland | 2.89 | 33 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Portugal | 1.96 | 23 | 0.30 | 17 | 6.58 | 14 |

| Quebec | 1.26 | 11 | 0.17 | 6 | 7.34 | 16 |

| Romania | 2.47 | 31 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Russian Federation | 0.47 | 8 | 0.99 | 26 | 0.48 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 2.33 | 28 | 0.30 | 18 | 7.73 | 17 |

| Slovakia | 4.12 | 39 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Slovenia | 0.42 | 6 | 0.06 | 4 | 7.09 | 15 |

| Spain | 1.56 | 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sweden | 0.24 | 4 | 0.05 | 3 | 5.19 | 8 |

| The Netherlands | 0.04 | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 4.78 | 7 |

| United Kingdom | 0.58 | 9 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Lowest use ranking = 1. NR Not reported,

2008 values,

2007 values

DISCUSSION

Prescribing of broad-spectrum penicillins and cephalosporins has declined in Canada from 1995 to 2010 by >41 and 23%, respectively, at the expense of increasing levels of quinolone and macrolide use (1). The results of the present study indicate that significant differences in β-lactam prescribing occurred among the provinces and over time. A decline in broad-spectrum penicillin prescribing occurred in all provinces from 1995 to 2004, followed by a levelling-off in the subsequent years in most provinces. However, a slight increase occurred in Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador from 2005 to 2010. Patterns of cephalosporin use were quite variable among the provinces over time. Nine of 10 provinces experienced an overall decline in cephalosporin prescribing from 1995 to 2010. An overall increase in cephalosporin prescribing was observed in Manitoba; however, this plateaued from 2005 to 2010. In contrast, an increase in cephalosporin prescribing was observed in Newfoundland and Labrador from 2004 to 2010. In both β-lactam groups in 2010, prescribing was significantly higher in Newfoundland and Labrador than other provinces, and significantly lower in Quebec.

Although the average DDD per prescription value in 2000 varied according to province, a common increase among the provinces occurred over time for the broad-spectrum penicillins. Furthermore, differences among the provinces in the DDDs per prescription measure may be due to the proportion of prescriptions dispensed to children, which is likely to vary among the provinces given that the provinces differ with regard to population structure. In contrast to the prescription rates, Quebec exhibited significantly higher broad-spectrum DDDs per prescription than all provinces with the exception of New Brunswick. These contrasting results may be the effect of campaigns in Quebec to reduce inappropriate prescribing for viral infections in children and, therefore, an increase in prescriptions for adults compared with prescriptions for children (authors’ unpublished observation). Furthermore, some of this increase in the DDDs per prescription measure may be explained by the new higher-dose prescribing guidelines for otitis media and other common bacterial infections, due to related increases in the minimum inhibitory concentrations (10). However, there is a current gap in studies investigating the impact of public health initiatives on levels of antimicrobial use. This information will better inform the trends observed when evaluating the DDDs per prescription measure.

Individual drug-level prescribing data were examined for Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec to explore the differences between these two provinces. In both provinces, amoxicillin was prescribed at much higher rates than the remaining penicillins. However, the difference in amoxicillin prescribing rates between Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec was considerable, suggesting that amoxicillin prescribing in Newfoundland and Labrador may be an important target for stewardship programs. Similarly, the most commonly prescribed cephalosporin in Newfoundland and Labrador, cephalexin, was prescribed at much higher rates than the most commonly prescribed cephalosporin in Quebec (cefprozil).

When compared with ESAC-Net data for antimicrobial use in 2009, use of penicillins in Canada was lower than the majority of reporting EU countries according to both the DID and PID measures. However, this was not true for all Canadian provinces, with Newfoundland and Labrador being ranked with much higher consumption than the remaining provinces. The DDD per prescription measure showed that the average Canadian penicillin prescription contained a larger amount of active ingredient for penicillin than in most reporting EU countries (3,4). Similarly, the use of cephalosporins in Canada was comparable with the reporting ESAC-Net countries according to DID and PrID measures, with the exception of Newfoundland and Labrador (ranked 36 of 43) and New Brunswick (35 of 43). Again, comparison of the DDD measurement revealed that the average Canadian prescription contained a larger amount of active ingredient than the reporting European countries (3,5). Discrepancies among the rankings for the three measures may be based on the age structure of the various populations because the average DDDs per prescription in a population is likely to be influenced by prescribing to children versus adults (1). However, the presence of, and adherence to, treatment guidelines is also likely to result in differences in the average DDDs dispensed per prescription in various countries, particularly if guidelines recommend increased strength, duration of treatment or a reduction in prescribing to children for illnesses of viral etiology. An assessment of antimicrobial use at the prescription level may be required to determine whether the strength and length of treatment choices are being made according to guidelines.

We acknowledge the limitations to our study, which include the lack of complete data for the period between 1995 and 1999, and the potential for nonrepresentativeness of measured pharmacies. However, despite missing prescription counts for the narrow-spectrum penicillins and individual drugs between 1995 and 1999, the prescription information for the broad-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporin classes represent sufficient information to describe trends in provincial use over time. Furthermore, the large proportion of pharmacies represented in the dataset (>67% of Canadian pharmacies in September 2011) and the extensive extrapolation method used by IMS Health Canada supports our belief that these data truly reflect antimicrobial use patterns in Canada (1,8). Our data also do not include information on the likely reason for prescribing. It appears to be likely that a decline in prescribing for aminopenicillins will most likely reflect less prescribing for various upper respiratory infections. On its own, this may indicate better compliance with prescribing guidelines. However, concomitant increases in macrolide and fluoroquinolone use may indicate that some of these upper respiratory infections are still being treated and with less appropriate first-line therapy.

Penicillins and cephalosporins are two of the three most often implicated antimicrobial classes that are inappropriately prescribed for viral infections, particularly of the respiratory tract (11,12). In an attempt to reduce the potential for selection of resistant bacteria while maintaining patient care standards, reducing prescribing of antimicrobials for viral infections and other diseases that do not benefit from antimicrobial therapy must continue to be a goal of the Canadian medical community.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER: This article was prepared using data from IMS Health Canada Inc. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed are those of the authors and not those of IMS Health Canada Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Government of Canada . Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) Human Antimicrobial Use Short Report, 2000–2009. Guelph: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass-Kaastra SK, Finley R, Hutchinson J, Patrick DM, Weiss K, Conly J. Variation in antimicrobial use patterns among Canadian provinces (1995–2010). 4th World Forum on Healthcare-Associated Infections, Les Pensières; Annecy, France. June 23 to 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, et al. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(Suppl 6):vi3–vi12. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Versporten A, Coenen S, Adriaenssens N, et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): Outpatient penicillin use in Europe (1997–2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011b;66(Suppl 6):vi13–vi23. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Versporten A, Coenen S, Adriaenssens N, et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): Outpatient cephalosporin use in Europe (1997–2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011b;66(Suppl 6):vi25–vi35. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases Community-Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Consultation Notes. 2010. < www.nccid.ca/files/caAMR_ConsultationNotes_final.pdf> (Accessed April 24, 2012)

- 7.Government of Canada . Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) 2008. Guelph: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2011. < www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cipars-picra/2008/index-eng.php> (Accessed June 11, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8.IMS Health Canada Unlocking the value of health information: how Canada’s healthcare community uses IMS evidence-based intelligence to improve healthcare. 2007. < www.imshealth.com/ims/Global/Content/Solutions/Solutions%20by%20Sector/Providers/ValueofHealthInformation.pdf> (Accessed April 24, 2012)

- 9.Statistics Canada Table 051-0001 – Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons), 1971 to 2010 (table), CANSIM (database), Using E-STAT (distributor). < www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a05?lang=eng&id=0510001> (Accessed March 21, 2012)

- 10.Dowell SF, Butler JC, Giebink GS, et al. Acute otitis media: Management and surveillance in an era of pneumococal resistance: A report from the Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hare ME, Gaur AH, Somes GW, Arnold SR, Shorr RI. Does it really take longer not to prescribe antibiotics for viral respiratory tract infections in children? Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang E, Einarson T, Kellner J, Conly J. Antibiotic prescribing patterns for respiratory tract infections in preschool children in Saskatchewan: Evidence for overprescribing for viral syndromes. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:155–60. doi: 10.1086/520145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]