Abstract

Urinary exosome-like vesicles (ELVs), 20–200nm membrane bound particles shed by renal epithelium, are emerging as an important source of protein, mRNA, and miRNA biomarkers to monitor renal disease. However, purification of ELVs is compromised by the presence of large amounts of the urinary protein Tamm-Horsfall Protein (THP). THP molecules oligomerize into long, double-helical strands several microns long. These linear assemblies form a 3-dimensional gel which traps and sequesters ELVs in any centrifugation based protocol. Here we present a purification protocol that separates ELVs from THP and divides urinary ELVs into three distinct populations.

Introduction

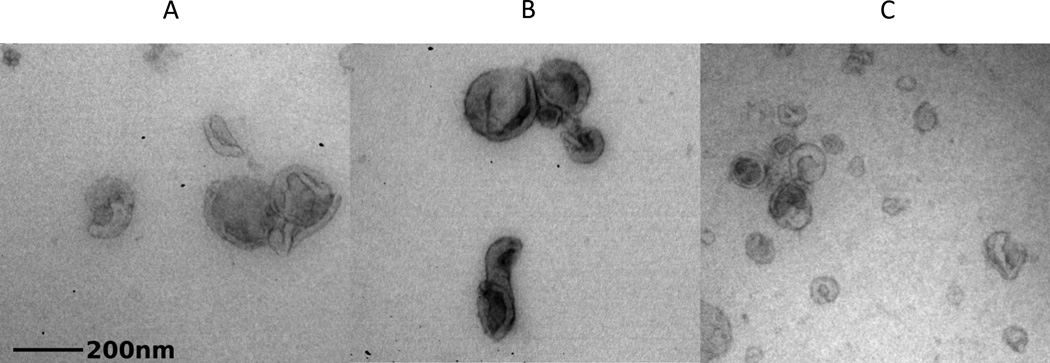

All body fluids contain 20–1000nm secreted extracellular vesicles which can be divided into three groups – exosomes, ectosomes, and apoptotic blebs (1). Exosomes are arguably the best characterized of these vesicle types. The biogenesis of exosomes begins with the invagination of intracellular endosomes to form multivesicular bodies (MVBs). The interior vesicles of the MVBs contain cytoplasmic cellular components as well as ESCRT-III subunits which are required for their formation. MVBs can either fuse with lysosomes for degradation, or they can fuse with the cell membrane. The latter releases the small invaginated vesicles into the outside environment as exosomes. Classical exosomes have a “deflated soccer-ball” appearance on transmission electron microscopy and are roughly 100nm in diameter (Figure 1). Reliable markers for exosomes include the tetraspanins CD63 and CD9, Alix, TSG101 and CD24. Alix and TSG101 are cytosolic proteins involved in multivesicular endosome biogenesis (2, 3). CD63, CD9, and CD24 are molecules believed to be involved in cell-cell adhesion and fusion (4–7). This indicates that exosomes can bind to neighboring cells transferring the cellular contents from the mother cell. Many recent studies have suggested that this passage of cellular cargo via ELVs in a range of body fluids plays a functional role in intracellular communication, immune system modulation, and nucleic acid exchange (8–11).

Figure 1.

Electron micrographs of ELVs purified from human urine. Letters designate the ELV fraction that corresponds with the image beneath it.

The second source of membrane bound vesicles in urine is the apical plasma membrane, perhaps including the primary cilium. Commonly used names for these particles include ectosomes, microvesicles, or membrane particles. These have an irregular morphology and variable size (100–1000nm). Ectosomes are characterized by the presence of integrins, selectins, CD40 ligand, and in the case of vesicles from the glomerular podocyte, podocalyxin and podocin (11–13).

The remaining extracellular vesicles are apoptotic blebs which are a by-product of programmed cell death. Apoptotic blebs are generally larger than exosomes and ectosomes with a size range of 50–5000nm. These vesicles are usually consumed by phagocytic cells and degraded.

It should be noted that because of the difficulties involved in purifying each of the vesicle populations and their inherent heterogeneity, the nomenclature for all of the above-mentioned vesicles is not yet standardized. For convenience, we will use the term ELVs to describe the subset of extracellular vesicles between 20 and 200nm that are obtained by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation of urine.

ELVs are secreted from all segments of the nephron and could be an important source of information about tubular and glomerular health (13). Specifically, ELVs contain proteins, microRNA, and mRNA that may be differentially expressed in health and disease (14–17). For example, liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has been used to identify 1412 proteins within normal human urinary exosomes (18). By comparing levels of these proteins to the levels found in disease patient urinary ELVs, disease markers can be identified. Some suggested protein markers include the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 and fetuin A for patients with acute kidney injury (19, 20) and polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 for patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (11, 21). Purification of urinary ELVs concentrates these biomarkers and allows detection of molecules that would be missed by typical urine analysis. In addition, in patients with renal disease up to 30% of urinary proteins in suspension are derived from plasma. The fact that these plasma-derived proteins can confound downstream analysis, reaffirms the importance of purifying ELVs from bulk urine (22–24).

Although ELVs are abundant in human urine, they are difficult to purify from the most common urinary protein, Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP) also known as uromodulin (UMOD). THP, which can reach concentrations of 1.5mg/mL, has a role in protecting the urinary tract from pathogens by acting as a decoy receptor, and it may also inhibit stone formation in supersaturated urine. The protein has a signal peptide cleaved mass of 67.1 kDa and a pI of 4.9. Because it is extensively glycosylated, THP runs as a smear at approximately 85 kDa on SDS PAGE. THP contains a disulfide cross-linked zone pellucida (ZP) domain that is responsible for its self-associating into long, double-helical fibrils.

Urine centrifugation is the classical ELV purification strategy. Under high g force, THP precipitates, contaminating the ELV pellet. Furthermore, when the pellet is resuspended, the THP forms a hydrated 3-dimensional gel that traps the ELVs. To recover the ELVs, dithiothreitol (DTT) can be used to reduce the disulfides in the ZP domain, break up the fibrils, and release the ELVs (25). However, this reduces all proteins, including ELV proteins, inactivating them and exposing their extended polypeptide backbones to proteolytic assault by endogenous proteases. To circumvent these issues, we devised a protocol with an extra centrifugation step that separates the THP from ELVs. Briefly, our protocol uses the THP precipitation to sweep ELVs from the chilled urine into the pellet. The resuspended pellet is then loaded onto a heavy-water 5–30% sucrose gradient. The heavy water has a density of 1.1g/ml, denser than normal water, and so is a sucrose sparing solvent that is dense but not osmotically active. It allows the ELVs to band at lower sucrose concentrations than in normal water and to some extent prevents alterations in ELV density due to the withdrawal of water (crenation). This allows the THP to separate from the ELVs. After the heavy water centrifugation, the THP is driven into the pellet while the ELVs form distinct bands in the sucrose gradient.

THP is normally secreted from the thick ascending loop of Henle (26). In contrast, ELVs are secreted from all major segments of the nephron (15). As such, there are multiple populations of ELVs in urine depending on their origin, and these populations separate into individual bands following heavy water centrifugation (Figure 1). The uppermost band expresses high levels of aquaporin-2 indicating that they derive from the collecting duct. The middle band is heavily enriched for the polycystin proteins, which are mutated in ADPKD. These ELVs are most likely shed from the proximal tubule as they are also megalin and aquaporin-1 positive. The most dense, bottom band contains ELVs with podocin, providing evidence of glomerular origin.

Materials

Collection bottles – 500 ml, 16 oz wide mouth (Nalgene)

Complete protease inhibitor cocktail – EDTA Free (Roche)

SLC-6000 rotor (Thermo)

Sorvall Revolution RC centrifuge

80 µm nylon mesh (Sefar)

1 L beaker

60 cc syringe

6” blunt Luer needle

Centrifuge tube polyallomer 90mL (Thermo)

T647.5 rotor (Thermo)

Spezialfett grease #3500 (Thermo)

DuPont Crimper for vial bottles (Sorvall)

150 mM NaCl solution

Balance (Mettler B2002S)

TH641 rotor (Thermo)

Sorvall Discovery 90SE ultra centrifuge

38.5 mL open-top clear ultra centrifuge tubes (Seton)

20mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) 0.25M Sucrose pH 6.0

Deuterium Oxide (D2O) Cat No. D16812 (Medical Isotopes Inc.)

30% sucrose solution in heavy water 20mM MES pH 6.0

5% sucrose solution in heavy water 20mM MES pH 6.0

SW41 2 Step Marker Block (BioComp)

Gradient Master (BioComp)

100% ethanol

0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)

Phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS)

12 mL open-top clear ultra centrifuge tubes (Seton)

Surespin 630 rotor (Sorvall)

AR200 Refractometer (Reichert)

1,1 dioctadectl-6, 6’-di(4-sulfophenyl)-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindocarbocyanide (SP-DilC18(3)) (Sigma)

1.5 mL clear plastic tubes (Eppendorf)

Methods

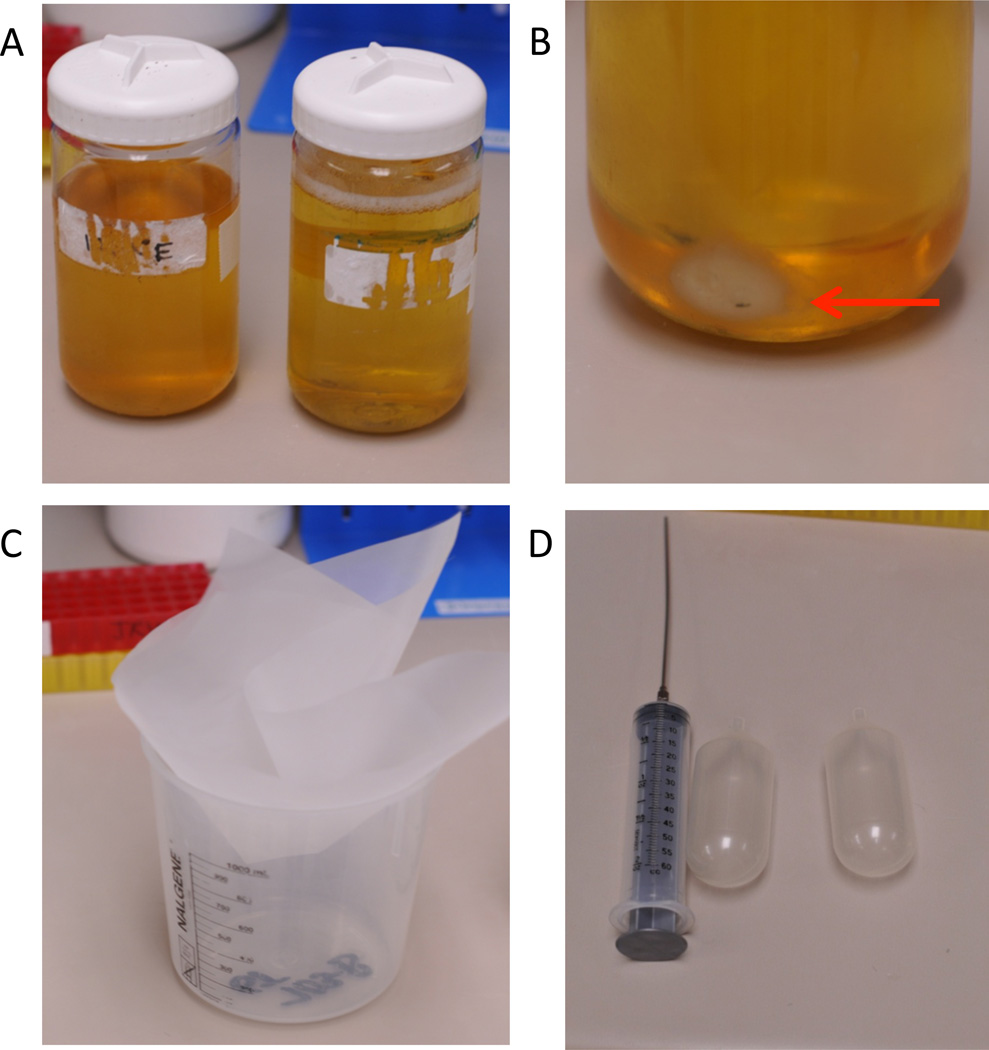

Collect fresh urine sample The best urine is generally the first morning void (Figure 2A). To ensure concentrated samples, individuals are encouraged not to consume large volumes of fluids after 9PM the evening prior to sample collection. Second morning urine samples have also been shown to contain high levels of total protein (27).

Figure 2.

Urine collection, centrifugation, and filtering. A. Fresh, never frozen, first morning void collected in Nalgene bottles. Sample volume is approximately 400 mL. Sample on the left, is slightly turbid and should be excluded from further processing. B. Red arrow points to the cell debris pellet obtained following initial centrifugation at 4,250rpm (4,000×g). C. Urine is passed through an 80 µm nylon filter which is placed into a clean beaker to collect the flow through. D. 60 mL syringe with a long, blunt Luer lock needle is used to transfer urine supernatant from the Nalgene bottle to the filter. The flow through is transferred into 90 mL plastic collection tubes using clean syringe and needle.

Occasionally, urine samples have high levels of phosphate precipitate. This can be evident at the time of collection, or precipitation can occur after storage. Because the precipitate may pull down exosomes, turbid urine samples should be excluded (Figure 2A).

Total volume of urine recommended to yield sufficient exosome quantities for proteomics is 200 mL.

Add protease inhibitor Immediately after the collection of the urine sample, protease inhibitor should be added to prevent degradation of the exosomal proteins. Our lab uses the commercially available protease inhibitor cocktail, Complete Protease Inhibitor EDTA-Free (Roche). One tablet is used per void urine sample. These tablets continuously inhibit cysteine and serine proteases.

Our laboratory does not typically freeze urine samples for long-term storage. It has been reported that there is greater than 70% loss of protein if urine is frozen at −20°C. However, it was shown that if urine is stored at −80°C (up to seven months), and vigorously vortexed while thawing at room temperature, yields can approach 100% of non-frozen samples (27).

Pellet cellular debris Samples are first centrifuged for 30 minutes at 4,275rpm (4,000×g) at room temperature in a Sorvall Revolution RC centrifuge. Nalgene bottles containing samples and their counter-balances are spun in a SLC-6000 fixed angle rotor. The centrifuge is set to accelerate at level 3 and decelerate at level 1 to prevent disruption of the pellet. Because the bottles are full, it is important to check that the rubber O-ring in the lid is securely in place and not kinked to prevent leakage. This spin pellets whole cells, large membrane fragments and other debris (Figure 2B).

Filter supernatant The supernatant is then passed through an 80µm nylon mesh to prevent the carryover of any pelleted material into subsequent centrifugation steps (Figure 2C). This is best achieved when urine supernatant is drawn into a high volume syringe (Figure 2D) and discharged into a beaker covered with the nylon. Pouring is not recommended as the pellet is unstable.

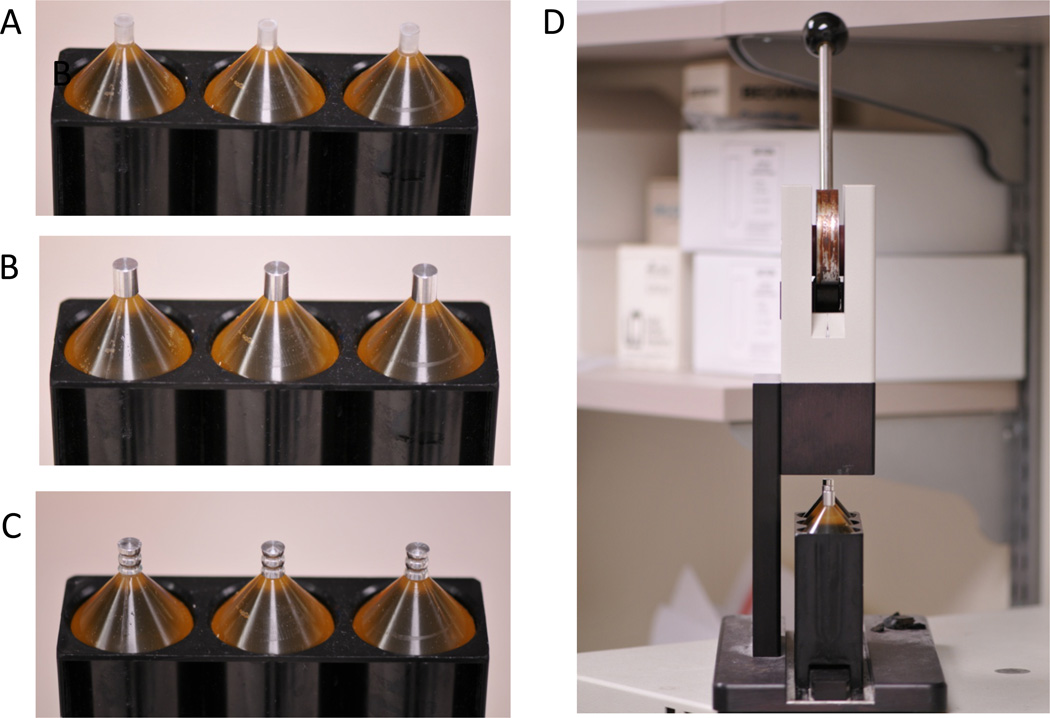

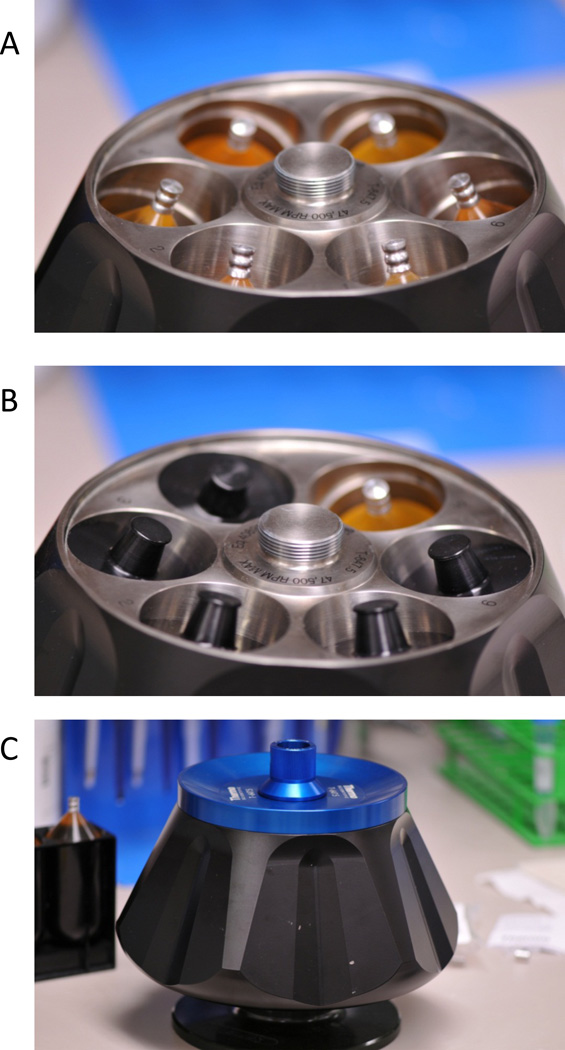

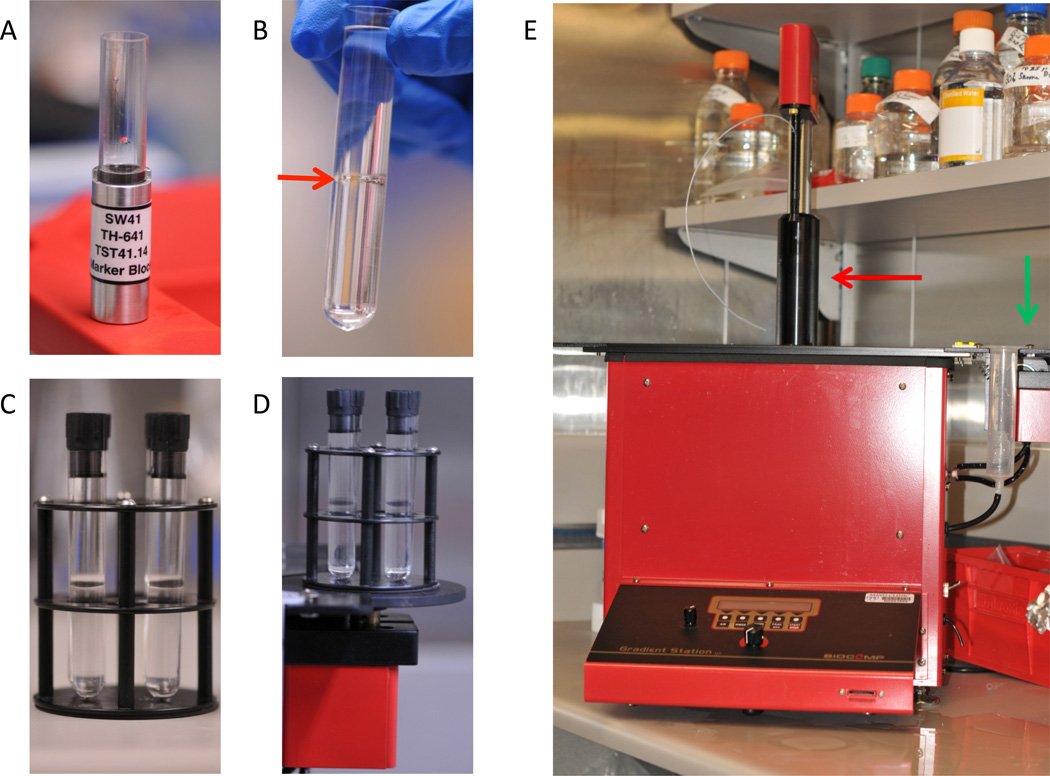

Pellet crude urinary ELVs Filtered urine supernatant is then aliquoted into 90ml tubes (Thermo, Ashville, NC Cat. No. 03990) (Figure 2C and Figure 3). To prevent the tubes from collapsing during the spin, fill the tubes to the neck leaving just enough space for the plug. When tubes have been balanced to within 0.01 grams with 150 mM NaCl saline solution, add the plastic plug and metal cap to each tube (Figure 3 A and B). (PBS is not recommended for balancing as the phosphates can precipitate.) Caps then need to be crimped with a Sorvall Crimper (Figure 3 C and D). Crimped tubes are loaded into a Thermo T647.5 fixed-angle rotor (Figure 4 A and C), and black rotor caps are affixed (Figure 4B). Caps should be checked to ensure that they are sufficiently lubricated. Add Thermo Spezialfett grease #3500 if needed. Samples are then spun at 45,000rpm (225,000×g) for 2 hours at 4°C in a Sorvall Discovery 90SE ultra centrifuge. Acceleration should be set at 9 and deceleration set at 1.

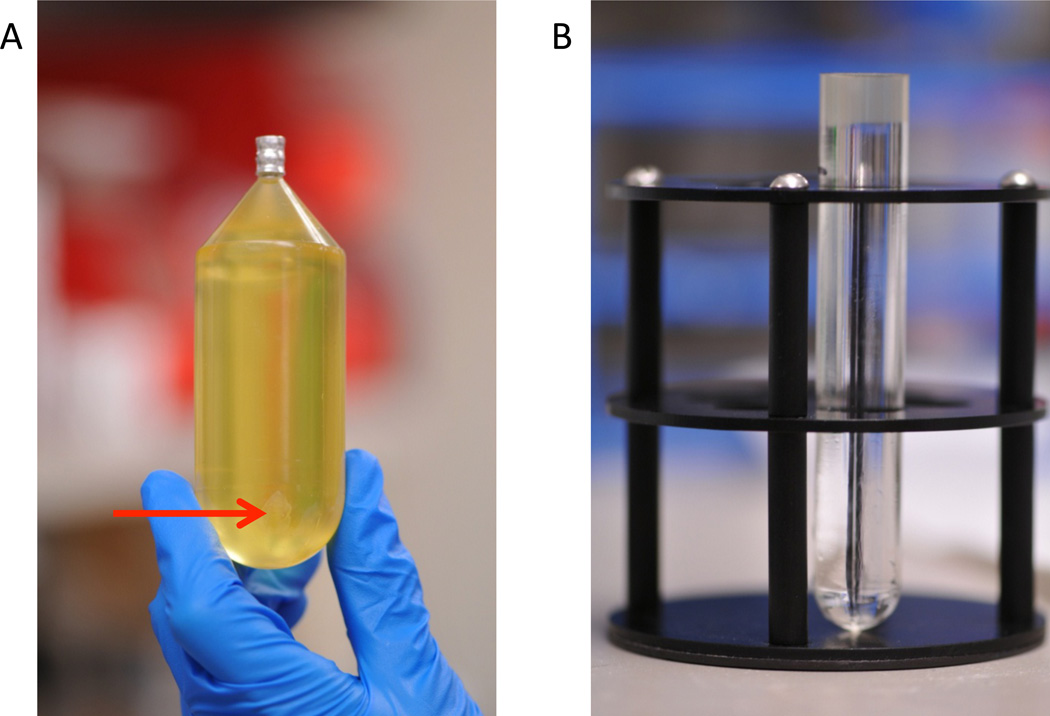

Prepare sucrose gradient While the ELVs are pelleting from the urine, a sucrose gradient can be prepared. Two gradient tubes should be prepared for each urine sample. It is critically important that the sucrose solutions are made in heavy water (deuterium oxide). The increased density allows for the separation between Tamm-Horsfall protein and ELVs. The 5% sucrose step is used to fill the Seton (Los Gatos, CA) open top, clear centrifuge tube (Part number 7030) up level with the top of the 2 step marker block (Figure 5A). A 30% sucrose step is laid below the 5% sucrose step (Figure 5B). It is important that these tubes be cleaned before use with 70% ethanol and allowed to dry. This will clean out any dust particles that will interfere with the ELV fractionation during ultracentrifugation. To convert the step gradient to a continuous gradient, the tubes are capped and placed into a magnetic holder (Figure 5C). The holder is placed onto a BioComp Gradient Master IP (Figure 5 D and E). Using the setting for SW41, run the program for “long sucrose 5→30”. The BioComp Gradient Master should be kept in a cold room for both generating the gradient and fractionation.

Remove Tamm Horsfall by ultracentrifugation on sucrose gradient When the urine has finished spinning (Figure 6A), the supernatant should be aspirated. The pellet should be resuspended in 20mM MES 0.25M sucrose, 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor EDTA-Free in deionized water at pH 6.0. This solution should be made fresh with a dissolved Complete Protease Inhibitor tablet immediately before use. Keep centrifuge tubes on ice during resuspension of the pellet. It may help to pool the resuspended pellets from common urine samples to increase the exosome band intensity. Cutting the top of the centrifuge off can make the pellet more accessible. The total volume of the resuspended crude exosome pellet should be 2.5 mL. One mL of each sample should be gently laid onto the top of the sucrose gradient (Figure 6B). Tubes should be balanced to within 0.01 grams using the MES sucrose buffer and loaded into a Thermo TH-641 swinging bucket rotor. Tubes are then spun at 40,000rpm (275,000×g) overnight at 4°C. Both acceleration and deceleration settings should be set at 1.

Figure 3.

Preparing to ultra centrifuge urine supernatant. A. Once urine is transferred to the narrow neck tubes, a plastic plug is inserted into the tube. B. Tubes are then capped with an aluminum cap. C. Tubes are sealed by crimping the aluminum caps. D. Sorvall Crimper.

Figure 4.

Loading the T647.5 rotor. A. Crimped tubes are placed into the T647.5 rotor. B. Tubes are stabilized with black caps. C. Rotor lid is positioned on top of the T647.5 rotor and the cap is screwed on to secure the lid.

Figure 5.

Preparing the sucrose gradient on the BioComp Gradient Master. A. SW41 marker block for the BioComp Gradient Master. Once centrifuge tube is loaded into the block, the 5% sucrose gradient is loaded into the tube until level with the top of the SW41 block. Then, 30% sucrose gradient is slowly loaded into the bottom of the tube until the centrifuge tube is filled 1/4” from the top. B. A clear demarcation between the upper 5% sucrose step and the lower 30% sucrose step is indicated with a red arrow. C. Black caps are added to the layered sucrose, and the tubes are placed into the magnetic holder. Sucrose containing tubes need to be capped securely with no air bubbles inside the tube. D. The magnetic holder is secured onto the magnetic platform of the Gradient Master. E. Biocomp Gradient Master. Green arrow points to the gradient maker arm. Red arrow points to the fractionator arm.

Figure 6.

Preparation of crude exosome pellet for heavy water sucrose ultra centrifugation. A. Crude exosome pellet following two hour spin at 225,000×g. Pellet (arrow) will be translucent and loosely bound to the plastic tube. B. Resuspended exosome pellet following 225,000×g (T-647.5) spin layered on top of the heavy water sucrose gradient.

The BioComp Gradient Master IP (Model 153) should be cleaned prior to using it to isolate gradient fractions. Specifically, the air tubing, water tubing, and ball bearings should be removed. The ball bearing should be submerged in warm 0.1% SDS, rinsed with ultra-pure water, and re-rinsed with 100% ethanol. Tubing should be flushed with 20 mL of the same SDS, water, and ethanol solutions. See manufacturer’s information (Part 3. Section 3 of the manufacturer’s operation manual) for more detailed cleaning instructions.

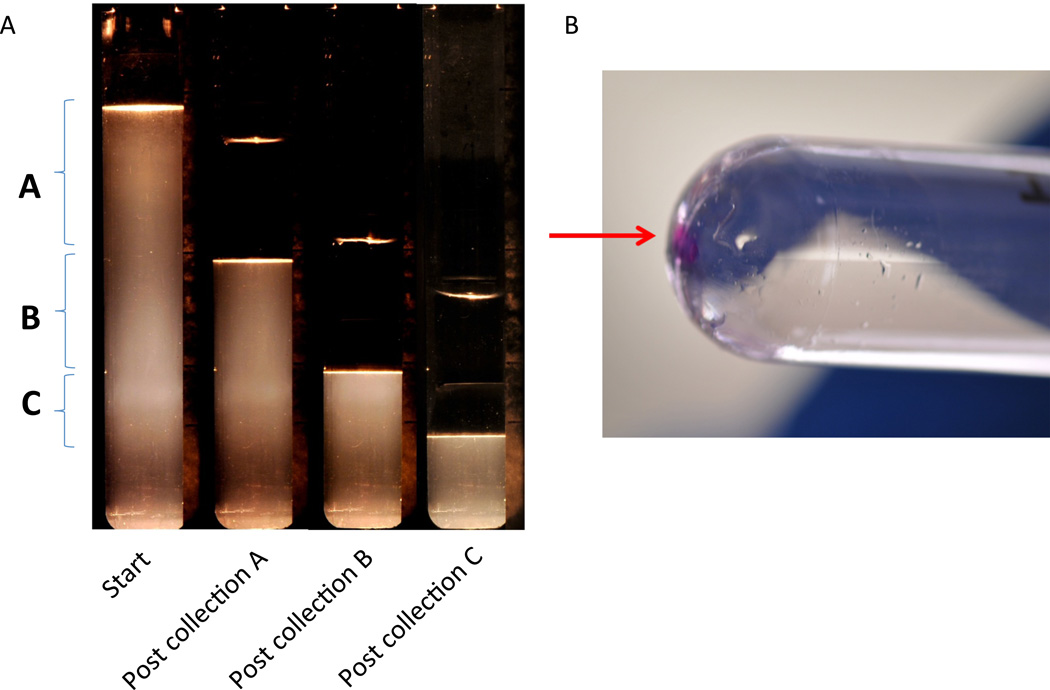

Preparing for Fractionation After the 275,000×g overnight spin, remove tubes. A small tan colored pellet should be visible at the base of the tube. This contains the Tamm-Horsfall protein. To set-up the fractionator, the tube holder is filled with ultra-pure water to the indicated mark and the buffer reservoir is filled with water. Select FRAC from the setup menu. Then, select EXIT to return to the main menu. Lines are primed by turning the knob clockwise and lowering the sample collector into a tube of ultra-pure water. After the collector has reached the bottom of the tube of water, purge the line by pressing AIR and then RINSE. Select EXIT to return to the main menu. Enter into the fractionation menu by selecting FRAC. Turn the motor on by twisting the dial counterclockwise. The centrifuge tube containing the banded exosomes is then gently but securely inserted into the black cap that fits into the tube holder. Place the cap and tube into the tube holder and place the tube holder back onto the fractionator. Turn on the light under the tube holder. The bands for the exosome fractions should now become visible (Figure 7A). Bands are typically diffuse, but three distinct exosome populations should be visible. Place a length of white tape on the tube holder assembly and delineate the position of the beginning and end of each ELV band using the BioComp cursor. (See page 24, section 9, “Manual Fractionation” in the BioComp Model 153 Gradient Station Manual (2005) for more information.) When the BioComp fractionator arm is aligned with the top of the band, the offset supplies the necessary dead volume required to collect the band completely.

Fractionation Use the Gradient Master knob to bring the piston down to the top of the gradient and press RSET. Continue to lower the piston until you reach the top of the first exosome band. This will be at approximately position 10. Clear the tubing by pulsing AIR, RINSE, AIR, RINSE, AIR. Next collect Fraction A by lowering the piston to the line drawn that separates the first two exosome bands. In our hands, this is typically at position 35. Cap the collection tube and pulse AIR, RINSE, AIR, RINSE, AIR. Fraction A contains aquaporin-2 rich exosomes, and thus, they are derived from collecting duct cells. Collect the second exosome fraction, Fraction B, in a second collection tube. This is usually between positions 35 and 50. Fraction B contains exosomes rich in polycystin-1 and the autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD) protein, fibrocystin. Rinse as before, and then collect the final band between positions 50 and 65. This is Fraction C and which is enriched for exosomes derived from podocytes in the glomeruli. Fraction C can be verified by probing for podocin expression (11). Thoroughly rinse the tubing before shutting down the BioComp Master.

Figure 7.

A. Serial photographs of the sucrose gradient following spin at 275,000×g (TH-641) loaded onto the Gradient Master and illuminated with light source. Time points are unfractionated (start), and post collection of the A, B, and C fractions. Bolded letters and their associated brackets define the boundaries of the A, B, and C fractions. B. Fluorescently stained exosome pellet (arrow) of Fraction B following centrifugation at 167,000×g (Surespin 630).

Check the refractive properties of each exosome fraction using a Reichert AR200 Refractometer. To calibrate, water should have a refraction of 1.33 and air should be 1. Vortex each collected fraction and load 100 µl onto the refractometer. Fraction A refractive index should be 1.34. Fraction B should be 1.35, and Fraction C should have a refraction of 1.36. Rinse with water between each measurement.

Concentrate individual exosome fractions To help visualize the eventual exosome pellet, it is useful to add 1µl of a fluorescent dye to each fraction. We use 1,1 dioctadectl-6, 6’-di(4-sulfophenyl)-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindocarbocyanide. (SP-DilC18(3)) Sigma Catalog number D7777. Load the exosome solution into a Seton open top polyclear centrifuge tube 1”× 3.5” (part number 7052). Fill the tube to within ¼” of the top using PBS with 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor EDTA-Free. Balance the remaining tubes with PBS. Spin the tubes overnight in a Sorvall Surespin 630 at 30,000rpm (167,000×g) for at least one hour. Remove the supernatant being careful not to dislodge the fluorescent pellet (Figure 7B).

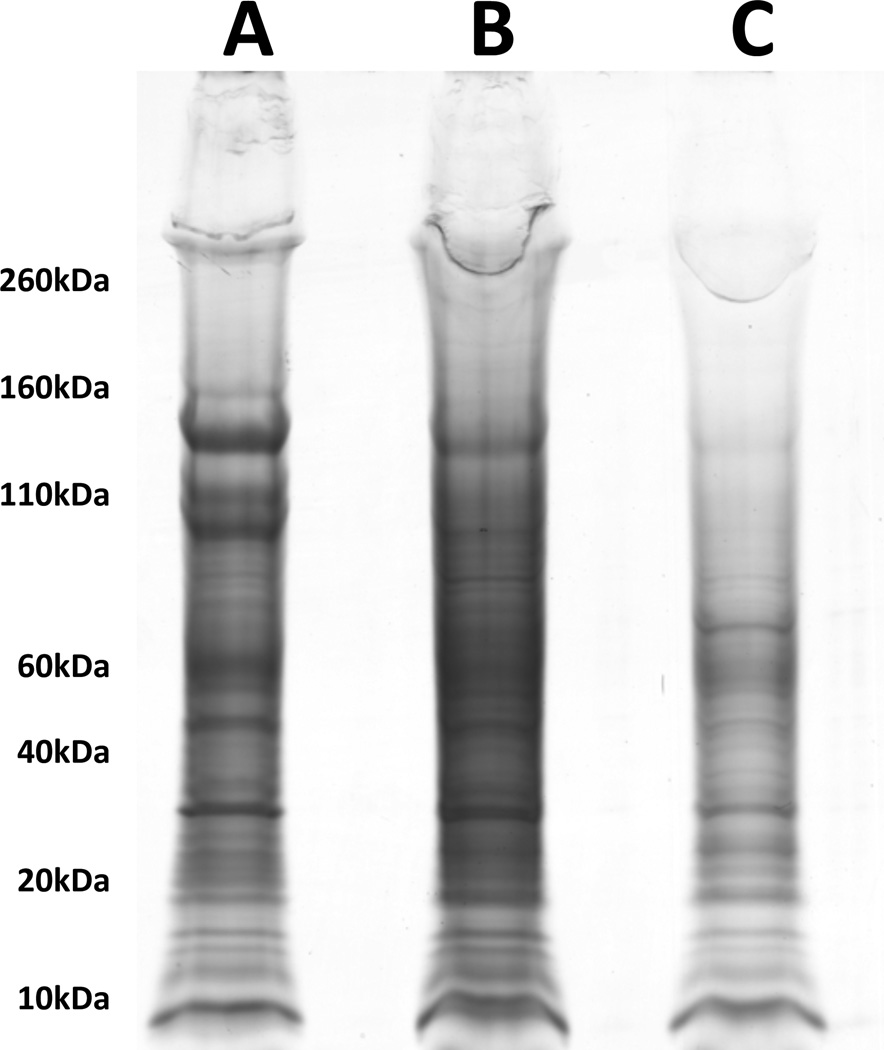

Downstream processing For protein work, exosomes can be stored in 20mM HEPES buffer with 0.25M sucrose at pH 7.4 with fresh 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor EDTA-free. To visualize differences in protein levels between the three ELV fractions, the resuspended exosomes can be run on a polyacrylamide gel followed by Coomassie staining (Figure 8). For microRNA isolation, add 200µl Trizol and transfer to an Eppendorf tube. Store at 4°C or freeze for long term storage. MicroRNA can be isolated using Qiagen’s miRNeasy components.

Figure 8.

BioSafe Coomassie (Bio-Rad) stain of SDS-PAGE of exosome fractions. Lanes for A, B, and C fractions are indicated. 10µl of resuspended exosomes were loaded onto a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel and run at 200V for 55 minutes. Sizes of reference bands are indicated on the left in kilodaltons (kDa).

Conclusions

In summary, urinary ELVs are a potential source of both protein and nucleic acids with diagnostic/prognostic value in evaluating kidney health. The major contaminant encountered when purifying these secreted vesicles is THP. By re-centrifuging THP contaminated ELV pellets in a heavywater sucrose gradient, we demonstrate that ELVs can be separated from THP. Furthermore, the ELVs can be separated into three distinct populations. While the polycystin-positive population derived from proximal tubules has been extensively characterized (11), further study of the Aquaporin-2 rich collecting duct ELVs as well as the podocin rich glomerular ELVs will likely provide insight into their function and may be useful in monitoring disease.

References

- 1.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. J Proteomics. 73:1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thery C, Boussac M, Veron P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Garin J, Amigorena S. J Immunol. 2001;166:7309–7318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:305–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi J, Kumar C, Zhang Y, Olsen JV, Mann M. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisitkun T, Johnstone R, Knepper MA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1760–1771. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600004-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller S, Rupp C, Stoeck A, Runz S, Fogel M, Lugert S, Hager HD, Abdel-Bakky MS, Gutwein P, Altevogt P. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1095–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Runz S, Keller S, Rupp C, Stoeck A, Issa Y, Koensgen D, Mustea A, Sehouli J, Kristiansen G, Altevogt P. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, Liejendekker R, Harding CV, Melief CJ, Geuze HJ. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1161–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zitvogel L, Regnault A, Lozier A, Wolfers J, Flament C, Tenza D, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Amigorena S. Nat Med. 1998;4:594–600. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A, Coscia C, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Molinari A, Colone M, Tatti M, Sargiacomo M, Fais S. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34211–34222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan MC, Manganelli L, Woollard JR, Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Tammachote R, Huang BQ, Leontovich AA, Beito TG, Madden BJ, Charlesworth MC, Torres VE, LaRusso NF, Harris PC, Ward CJ. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:278–288. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomura S, Shouzu A, Omoto S, Nishikawa M, Iwasaka T, Fukuhara S. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2004;10:205–215. doi: 10.1177/107602960401000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasser O, Hess C, Miot S, Deon C, Sanchez JC, Schifferli JA. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knepper MA, Pisitkun T. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1043–1045. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranda KC, Bond DT, McKee M, Skog J, Paunescu TG, Da Silva N, Brown D, Russo LM. Kidney Int. 78:191–199. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales PA, Pisitkun T, Hoffert JD, Tchapyjnikov D, Star RA, Kleta R, Wang NS, Knepper MA. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:363–379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Cheyron D, Daubin C, Poggioli J, Ramakers M, Houillier P, Charbonneau P, Paillard M. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Pisitkun T, Aponte A, Yuen PS, Hoffert JD, Yasuda H, Hu X, Chawla L, Shen RF, Knepper MA, Star RA. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1847–1857. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoorn EJ, Pisitkun T, Zietse R, Gross P, Frokiaer J, Wang NS, Gonzales PA, Star RA, Knepper MA. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thongboonkerd V, McLeish KR, Arthur JM, Klein JB. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1461–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pieper R, Gatlin CL, McGrath AM, Makusky AJ, Mondal M, Seonarain M, Field E, Schatz CR, Estock MA, Ahmed N, Anderson NG, Steiner S. Proteomics. 2004;4:1159–1174. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thongboonkerd V, Malasit P. Proteomics. 2005;5:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez-Llama P, Khositseth S, Gonzales PA, Star RA, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. Kidney Int. 77:736–742. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachmann S, Metzger R, Bunnemann B. Histochemistry. 1990;94:517–523. doi: 10.1007/BF00272616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H, Yuen PS, Pisitkun T, Gonzales PA, Yasuda H, Dear JW, Gross P, Knepper MA, Star RA. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1471–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]