Abstract

Rationale: The relationship between self-efficacy and health behaviors is well established. However, little is known about the relationship between self-efficacy and health-related indicators among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Objectives: The purpose of this cross-sectional cohort study was to test the hypothesis that the total score and specific subdomain scores of the COPD Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) are associated with functional capacity and quality of life in a group of patients with moderate to severe COPD.

Methods: Relationships were examined in a cross-sectional study of baseline data collected as part of a randomized trial. Self-efficacy was measured using the five domains of the CSES: negative affect, emotional arousal, physical exertion, weather/environment, and behavioral. Measures of quality of life and functional capacity included SF-12: physical and mental composite scores, Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire dyspnea domain, and the 6-minute-walk test. Statistical analyses included Spearman correlation and categorical analyses of self-efficacy (“confident” vs. “not confident”) using general linear models adjusting for potential confounders.

Measurements and Main Results: There were 325 patients enrolled with a mean age (standard deviation) of 68.5 (9.48) years, 49.5% male, and 91.69% non-Hispanic white. The negative affect, emotional arousal, and physical exertion domains were moderately correlated (range, 0.3–0.7) with the SF-12 mental composite score and Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire dyspnea domain. In models exploring each CSES domain as “confident” versus “not confident” and adjusting for age, sex, race, pack-years, and airflow obstruction severity, there were multiple clinically and statistically significant associations between the negative affect, emotional arousal, and physical exertion domains with functional capacity and quality of life.

Conclusions: The aggregated total CSES score was associated with better quality of life and functional capacity. Our analysis of subdomains revealed that the physical exertion, negative affect, and emotional arousal subdomains had the largest associations with functional capacity and quality of life indicators. These findings suggest that interventions to enhance self-efficacy may improve the functional capacity and quality of life of patients with moderate to severe COPD.

Keywords: COPD, dyspnea, self-efficacy, quality of life

Self-efficacy is a psychological construct defined as an individual’s beliefs about their capabilities to control events that affect their lives (1). These beliefs may be measured using general or event-specific scales. Furthermore, aggregate measures of self-efficacy have been associated with behavior change as well as short- and long-term quality of life (2, 3). However, little is known about event-specific domains of self-efficacy and health status among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

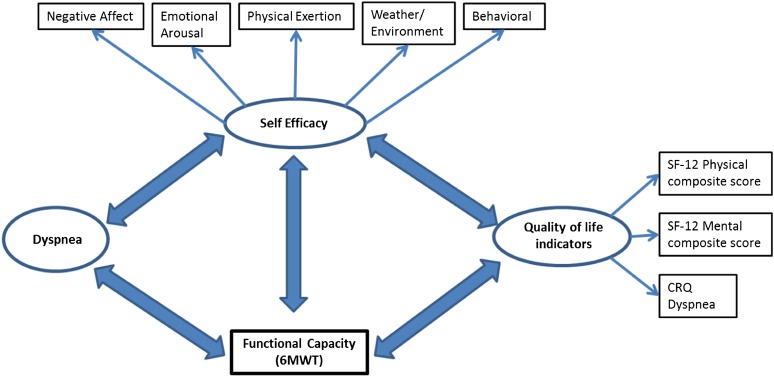

For patients with COPD, the ability to manage dyspnea is an event-specific challenge that has a major impact on functional performance and quality of life. Indeed, evidence suggests that self-efficacy in managing dyspnea predicts physical functioning as well as survival among patients with COPD (4, 5). However, the role of psychological interventions to enhance self-efficacy for managing dyspnea has received little attention (6). Previous studies of self-efficacy among patients with COPD have been limited by small sample sizes and use of aggregate measures (5, 7–10). Little is known about the relationships between domain-specific components of self-efficacy, dyspnea, functional capacity, and quality of life, which are complex (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for self-efficacy and its association with functional capacity and quality of life indicators. 6MWT = 6-minute-walk test; CRQ = Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to examine the relationships between the COPD Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES), total and subdomain scores; and measures of functional capacity and quality of life in a group of patients with moderate to severe COPD. We hypothesized that higher CSES scores in each subdomain would be associated with improved functional capacity and quality of life. In contrast to analyses of aggregated measures of self-efficacy described in previous literature, this analysis adds new evidence on associations between event-specific subdomains and health status. These findings may aid researchers and practitioners in targeting interventions to specific self-efficacy subdomains, which in turn may have greater effectiveness for improving patients’ health. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (11).

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This was a cross-sectional study of baseline data collected from patients with COPD enrolled in a self-management randomized clinical trial to test the effectiveness of a behavioral intervention designed to enhance daily lifestyle physical activity. The study design and methods have been described previously (12). Briefly, patients were enrolled from primary care and pulmonary specialty clinics of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler (Tyler, TX), an academic medical center in eastern Texas. Patients were eligible for pulmonary rehabilitation and at least 45 years of age with physician-diagnosed COPD, and postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC less than 70% and FEV1 less than 70%. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler approved the study entitled “Trial of Physical Activity Self-Management Intervention for Patients with COPD” funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; R18HL092955-01A1; principal investigator, D. Coultas). Drafting of this manuscript adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies (13).

Measures

Self-efficacy was measured with the CSES (14), which is a 34-item disease-specific questionnaire developed to measure confidence in managing or avoiding dyspnea across five domains: negative affect, emotional arousal, physical exertion, weather/environment, and behavioral. Responses in each domain are ranked on a five-point Likert scale: 1, very confident to 5, not at all confident. Higher scores correspond to lower confidence in managing and controlling dyspnea. The CSES has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.95) as well as good test–retest reliability (0.77) (5, 9, 14). The computed Cronbach’s α from our study was 0.97, which is similar to the suggested value of 0.95 by Wigal and coworkers (14).

Functional capacity was assessed by 6-minute-walk test (6MWT) distance, using standard procedures (15, 16). Health-related quality of life (HRQL) was measured with the physical and mental composite scores of the generic SF-12 (12-item Short Form Health Survey) (17) and the dyspnea domain of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) (18). The physical and mental composite scores of the SF-12 range from 0 to 100, where the general population scores are centered at 50; higher scores suggest higher HRQL (17, 19). The CRQ is a 20-item questionnaire that measures both physical and emotional aspects of chronic respiratory disease. There are four domains: dyspnea, fatigue, emotional function, and mastery. Items on the CRQ are measured using a seven-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQL (20).

Data Analysis

The participant characteristics are presented as means and standard deviation or as medians and interquartile range for continuous variables, and as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between CSES subdomains and each health status indicator.

General linear models were used to analyze the relation between self-efficacy and health indicators adjusting for age, sex, race, and factors associated with dyspnea including pack-years of smoking and severity of airflow obstruction based on Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage (21). Initially we used aggregated total CSES score as the primary explanatory variable in a general linear model to compare our results with other studies (8, 22). This was followed by examination of each subdomain of the CSES in the general linear models. The aggregated CSES score was calculated as the sum of all nonmissing responses (maximal total score, 170) divided by the maximal score from nonmissing responses (8, 22). This results in a proportion that ranges between 0 and 1, where lower proportions indicate higher levels of confidence. We categorized proportions that were less than 0.5 as “confident” and those greater than or equal to 0.5 as “not confident.” For analysis of the subdomains, the initial CSES domain distributions were dichotomized into “confident” and “not confident” to group patients who had some degree of confidence in managing or avoiding breathing difficulty and those with little or no degree of confidence (22). “Confident” was defined as those with mean CSES domain scores not greater than 2, corresponding to “very/pretty confident”; whereas “not confident” was defined as those with mean domain scores greater than 2, corresponding to “somewhat/not very/not at all confident.” Multicollinearity of independent variables was assessed with the variance inflation factor. The minimal clinically important differences used for each health indicator were as follows: SF-12 physical composite score = 3 (23), SF-12 mental composite score = 3.5 (19), CRQ = 0.5 (24), and 6MWT = 25–35 m. The range of 6MWT differences was based on minimal clinically important differences found among patients with both stable and severe COPD (25–27). The threshold for statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 325 patients were enrolled with 49.5% male, 91.7% non-Hispanic white, and averaged 68.5 years of age (Table 1). Approximately 93% were classified as current or ex-smokers, with a median of 50.8 pack-years. The severity of spirometric impairment was predominantly moderate (43.8) and severe (41.9).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 68.47 (9.48) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 161 (49.54) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (1.23) |

| NH white | 298 (91.69) |

| NH black | 22 (6.77) |

| NH other | 1 (0.31) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 83 (25.54) |

| Ex-smoker | 219 (67.38) |

| Never-smoker | 23 (7.08) |

| Pack-years, median (IQR) | 50.84 (35.39, 74.54) |

| GOLD stage, n (%) | |

| II | 142 (43.83) |

| III | 136 (41.98) |

| IV | 46 (14.2) |

Definition of abbreviations: GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IQR = interquartile range; NH = non-Hispanic.

Note: Number of patients with COPD = 325.

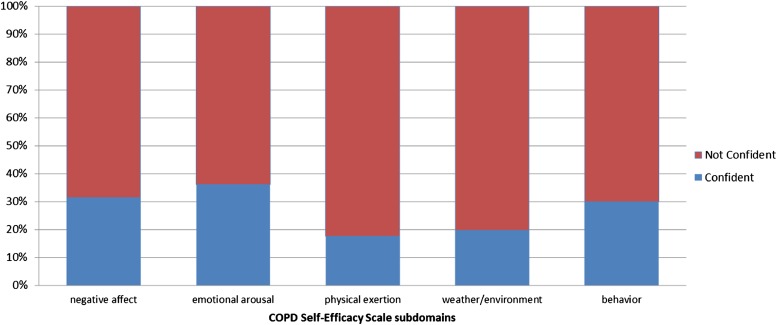

On average, the SF-12 physical composite score of 31.98 was lower compared with the general population mean of 50, whereas the mental composite score was similar to the general population mean of 50 (Table 2). The average 6MWT distance of 338.2 m was similar to that of other patients with COPD (342.6 m) (16), but lower than for the healthy elderly (28, 29). The mean CRQ dyspnea score of 4.69 was greater than the mid-point of the range (1 = best quality of life and 7 = worst quality of life). Average domain-specific self-efficacy scores were 2.39 to 3.01, or “somewhat confident” in managing dyspnea. For all domains, only a minority of patients were categorized as “confident” (Figure 2). Approximately 30% of the sample was considered “confident” in the domains of negative affect, emotional arousal, and behavioral, whereas only about 19% were considered “confident” in the physical exertion and weather/environment domains.

Table 2.

Distribution of COPD Self-Efficacy Scale subdomains and functional capacity and quality of life indicators

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| COPD Self-Efficacy Scale domain | |

| Negative affect | 2.54 (0.88) |

| Emotional arousal | 2.39 (0.79) |

| Physical exertion | 3.01 (0.92) |

| Weather/environment | 2.78 (0.84) |

| Behavior | 2.69 (0.90) |

| Functional capacity and quality of life indicators, mean (SD) | |

| SF-12 physical component score | 31.98 (8.85) |

| SF-12 mental component score | 50.43 (11.15) |

| 6-minute-walk test distance, m | 338.17 (96.8) |

| CRQ Dyspnea | 4.69 (1.3) |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRQ = Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

Note: Number of patients with COPD = 325.

Figure 2.

Distribution of confident and not-confident patients for subdomains of the COPD Self-Efficacy Scale.

As hypothesized, patients with higher confidence had higher HRQL with significant (P < 0.05) inverse correlations between all domains of the CSES and SF-12 physical composite score, mental composite score, and CRQ dyspnea (see Table E1 in the online supplement). For the 6MWT, physical exertion was the only subdomain with significant inverse correlations. There were multiple statistical and clinically significant associations between the dichotomized (“confident” vs. “not confident”) CSES aggregated score, individual subdomain scores, and health indicators (see Table E2 in the online supplement). Several of the estimated differences between “confident” and “not confident” subjects exceeded the minimally clinically important difference thresholds. For the physical composite score, confidence in the physical exertion (β = 6.06, P < 0.0001) and weather/environment (β = 5.03, P < 0.0001) subdomains had the largest differences. Negative affect (β = 8.63, P < 0.0001) and emotional arousal (β = 7.92, P < 0.0001) subdomains had the greatest effect on mental composite score. The differences in CRQ dyspnea scores between “confident” versus “not confident” were largest for the behavioral (β = 0.87, P < 0.0001), emotional arousal (β = 0.83 P < 0.0001), and physical exertion (β = 0.82, P < 0.0001) domains. Patients who were confident in the physical exertion domain walked an average of 27.63 m (p = 0.0309) further than those who were not confident.

Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that both the aggregated total CSES score as well as various subdomain scores are associated with measures of functional capacity and quality of life. For measures of quality of life, only the negative affect subdomain failed to exceed the threshold for clinical and statistical significance for the SF-12 physical composite score, suggesting that the control of breathlessness when dealing with anxiety, frustration, and depression may have limited impact on physical HRQL. In addition, confidence in the physical exertion subdomain was associated with an average 6MWT distance of 27.63 m more compared with patients who were not confident (P = 0.03), which is within the 25- to 35-m range that has been considered a clinically important difference (27). A large proportion of patients with COPD may be classified as “not confident” across all subdomains of the CSES. Furthermore, the construct validity of the CSES domains is supported by associations between higher self-efficacy among all dyspnea-specific domains and better functional capacity and quality of life. Confidence in managing dyspnea with physical exertion was the only subdomain where differences between “confident” and “not confident” exceeded thresholds for clinical and statistical significance for all health indicators. Therefore, confidence in controlling dyspnea when “exercising, climbing stairs, lifting objects, or rushing around” may have a greater impact on patients’ physical and mental health than any other subdomain.

Our data support previous reports and add new evidence about the influence of specific self-efficacy subdomains on several indicators of health status. Other studies have reported similar results, but these have been based on an aggregate measure of self-efficacy. In a convenience sample of 97 men and women, Siela (7) found that self-efficacy predicted functional performance in men but not women. Although this study measured self-efficacy using the CSES, it averaged all subdomain scores to estimate the effect. Similarly, Garrod and colleagues (8), found an association between higher aggregate self-efficacy using the CSES, and higher health status and greater exercise tolerance. Scherer and colleagues (22) used a pre–post study to examine changes after pulmonary rehabilitation in CSES subdomains as well an aggregate score and found that there was a significant change in scores. However, only two subdomains exceeded the threshold for statistical significance. In a study using a different self-efficacy instrument, the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy (PRAISE), Vincent and colleagues (10) found that pre–post pulmonary rehabilitation changes in self-efficacy were all positive and significant for different Medical Research Council dyspnea grades. The PRAISE score is an aggregate of general self-efficacy and pulmonary rehabilitation specific measures. Questions have been raised about what the PRAISE score actually measures (30). Aggregation of subdomains into a single score may be misleading because the process may alter what the original scales were intended to measure. By combining individual scores, details on information contained in specific domain scores may be lost, which in turn may bias results.

This may be useful in tailoring treatments to patients’ needs. For instance, if the 6MWT is chosen to measure improvements in patient’s physical activity, then education and behavioral practice designed to improve self-efficacy on how to manage dyspnea during physical activities would be more beneficial than targeting dyspnea-coping strategies for anxiety and frustration. To our knowledge there have been no studies investigating how targeting different subdomains of the CSES affects patient health over time.

These results should be considered in light of several limitations. Causal inferences between self-efficacy and health indicators cannot be confirmed with the cross-sectional design. Moreover, it is not clear whether low physical or mental health status affected self-efficacy for managing dyspnea or vice versa (Figure 1). Generalizability of the results may be limited because study patients were enrolled as part of a clinical trial from a single institution. However, the recruitment strategy was designed to enroll a representative sample of patients and to limit selection bias (12). The sample was predominantly GOLD stage II and III (85.81%) and non-Hispanic white (91.69%). Underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities is an inherent problem of clinical trials (31). On the other hand, the distribution of spirometric impairment is representative of clinic samples of patients with COPD intermediate between primary care (32) and specialty care samples (33).

These results suggest that there are clinically relevant and statistically significant associations between all CSES subdomains, and measures of HRQL and functional capacity among patients with COPD. The literature on psychological interventions that target self-efficacy for managing dyspnea has not been sufficiently addressed (6), and these results provide specific intervention targets for future investigations. Interventions to enhance confidence in managing dyspnea in situations involving depression, anxiety, excitement, and physical exertion may provide the largest potential benefit for the physical and mental health of patients with COPD.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the study participants and research staff members Toyua Akers and Ginny Harleston, and the staff of University of Texas Health Science Center-Tyler Cardiopulmonary Services.

Footnotes

Supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI R18HL092955).

Author Contributions: B.E.J., D.B.C., J.A., K.P.S., and S.B. were involved in the conception, hypothesis generation, and design of the study. B.E.J., K.P.S., M.U., and S.B. were involved in the statistical analysis. D.B.C., R.R., and J.P. were involved in the acquisition of data and interpretation of results.

This article has an online supplement, which is available from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bandura A. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. Social learning theory. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1986;13:73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones F. Strategies to enhance chronic disease self-management: how can we apply this to stroke? Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:841–847. doi: 10.1080/09638280500534952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan RM, Ries AL, Prewitt LM, Eakin E. Self-efficacy expectations predict survival for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Psychol. 1994;13:366–368. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentsen SB, Wentzel-Larsen T, Henriksen AH, Rokne B, Wahl AK. Self-efficacy as a predictor of improvement in health status and overall quality of life in pulmonary rehabilitation—an exploratory study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, Calverley PM, Gift AG, Harver A, Lareau SC, et al. American Thoracic Society Committee on Dyspnea. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siela D. Use of self-efficacy and dyspnea perceptions to predict functional performance in people with COPD. Rehabil Nurs. 2003;28:197–204. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2003.tb02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrod R, Marshall J, Jones F. Self efficacy measurement and goal attainment after pulmonary rehabilitation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:791–796. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherer YK, Schmieder LE. The effect of a pulmonary rehabilitation program on self-efficacy, perception of dyspnea, and physical endurance. Heart Lung. 1997;26:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent E, Sewell L, Wagg K, Deacon S, Williams J, Singh S. Measuring a change in self-efficacy following pulmonary rehabilitation: an evaluation of the PRAISE tool. Chest. 2011;140:1534–1539. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson BE, Coultas D, Russo R, Peoples J, Uhm M, Singh KP, Ashmore J, Bae S. Self-efficacy in coping and managing dyspnea significantly affects health outcomes among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A2338. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashmore J, Russo R, Peoples J, Sloan J, Jackson BE, Bae S, Singh KP, Blair SN, Coultas D. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Self-Management Activation Research Trial (COPD-SMART): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez E STROBE Group. [Observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE)] Med Clin (Barc) 2005;125:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(05)72209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wigal JK, Creer TL, Kotses H. The COPD Self-Efficacy Scale. Chest. 1991;99:1193–1196. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sciurba F, Criner GJ, Lee SM, Mohsenifar Z, Shade D, Slivka W, Wise RA National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1522–1527. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-166OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JKM, Keller S. Boston, MA: Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scores. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JE, Singh SJ, Sewell L, Guyatt GH, Morgan MD. Development of a Self-Reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ-SR) Thorax. 2001;56:954–959. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.12.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Kosinsky M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. User’s manual for the SF-12 health survey. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schünemann HJ, Puhan M, Goldstein R, Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH. Measurement properties and interpretability of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ) COPD. 2005;2:81–89. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Ma P, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS GOLD Scientific Committee. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care. 2001;46:798–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherer YK, Schmieder LE, Shimmel S. The effects of education alone and in combination with pulmonary rehabilitation on self-efficacy in patients with COPD. Rehabil Nurs. 1998;23:71–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1998.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PW, Brusselle G, Dal Negro RW, Ferrer M, Kardos P, Levy ML, Perez T, Soler-Cataluña JJ, van der Molen T, Adamek L, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients by COPD severity within primary care in Europe. Respir Med. 2011;105:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puhan MA, Chandra D, Mosenifar Z, Ries A, Make B, Hansel NN, Wise RA, Sciurba F National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. The minimal important difference of exercise tests in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:784–790. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00063810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland AE, Hill CJ, Rasekaba T, Lee A, Naughton MT, McDonald CF. Updating the minimal important difference for six-minute walk distance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland AE, Nici L. The return of the minimum clinically important difference for 6-minute-walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:335–336. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2191ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casanova C, Celli BR, Barria P, Casas A, Cote C, de Torres JP, Jardim J, Lopez MV, Marin JM, Montes de Oca M, et al. The 6-min walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from seven countries. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:150–156. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00194909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:270–274. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b06.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Depew ZS, Benzo R. What is the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy tool actually measuring? Chest. 2012;141:1123–1124, author reply 1124. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durant RW, Davis RB, St George DM, Williams IC, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith GM. Participation in research studies: factors associated with failing to meet minority recruitment goals. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruis AL, Boland MR, Schoonvelde CH, Assendelft WJ, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Gussekloo J, Tsiachristas A, Chavannes NH. RECODE: design and baseline results of a cluster randomized trial on cost-effectiveness of integrated COPD management in primary care. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira JC, de Carvalho Aguiar I, de Oliveira Beloto AC, Santos IR, Filho FS, Sampaio LM, Donner CF, Oliveira LV. Clinical significance in COPD patients followed in a real practice. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8:43. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]