Abstract

Single nucleotide polymorphisms within microRNA (miRNA) binding sites comprise a novel genre of cancer biomarkers. Since miRNA regulation is dependent on sequence complementarity between the mRNA transcript and the miRNA, even single nucleotide aberrations can have significant effects. Over the past few years, many examples of these functional miRNA binding site SNPs have been identified as cancer biomarkers. While most of the research to date focuses on associations with cancer risk, more and more studies are linking these SNPs to cancer prognosis and response to treatment as well. This review summarizes the state of the field and draws importance to this rapidly expanding area of cancer biomarkers.

Keywords: single nucleotide polymorphism, microRNA, microRNA binding site, 3'-untranslated region, cancer, biomarker, personalized medicine

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the development of genomic sequencing, there has been an intense effort to identify genetic mutations that can help us better predict, diagnose, and treat cancer. The most frequently identified mutations in the genome are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), variations of just one nucleotide. SNPs occur once every several hundred base pairs throughout the genome.1 Until recently, the predominant focus for cancer causing SNPs has been limited to nonsynonymous SNPs, those within the protein coding domain that alter the amino acid sequence and, therefore, the protein structure and function of a gene. The majority of SNPs, however, do not alter the amino acid sequence. More and more we are finding that these so-called silent polymorphisms, many of which reside in non-coding regions of the genome, are actually functional. Importantly, these non-coding regions include microRNAs and microRNA target sites.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small (18–24 nucleotide) non-coding RNAs that negatively regulate protein expression by directly binding to mRNA transcripts, typically the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR).2 This binding then induces transcript cleavage or translational repression depending on the level of complementarity between the miRNA and mRNA.2 Computational analysis predicts that up to 1000 miRNAs exist within the human genome and each miRNA can bind to up to 100 different sites.3,4 As a result, miRNAs are predicted to regulate up to 30% of protein coding genes, and are implicated in almost all cellular processes.4–6

Since miRNA regulation is dependent on sequence complementarity, it follows that variation in either the mRNA or miRNA sequence will have significant effects. The most critical region for complementarity is the seed region (nucleotides 2–7 from the 5'-terminus of the miRNA).4,7 Aside from the seed region, other criteria have been established that can enhance miRNA-mediated repression including complementarity at position 8 and the presence of an adenosine residue opposite the first miRNA nucleotide.8,9 Any polymorphism that interferes with these critical regions will affect miRNA regulation either by disrupting or creating a miRNA binding site.10 In fact, miRNA binding site regions are evolutionarily conserved such that there is a lower SNP density within miRNA binding sites than in control sites.11 This suggests that there is a negative selective pressure on mutations in these regions of the genome since they are critical for cellular function and survival.

II. The Search for MiRNA Binding Site SNPs

A large number of algorithms has been developed to identify miRNA targets5,6 as have programs to identify SNPs that will affect miRNA binding.12,13 The program MiRanda5 takes into account the degree of complementarity and whether the seed sequence resides in an evolutionarily conserved region. TargetScan4 identifies segments with perfect complementarity to the seed region. RNA Hybrid14 calculates Gibbs Free Energy to determine favorable binding interactions between miRNAs and mRNA transcripts. The strength of binding, or Gibbs Free Energy, for both the wild type and variant alleles can then be calculated in order to determine if a specific polymorphism will impact miRNA binding.

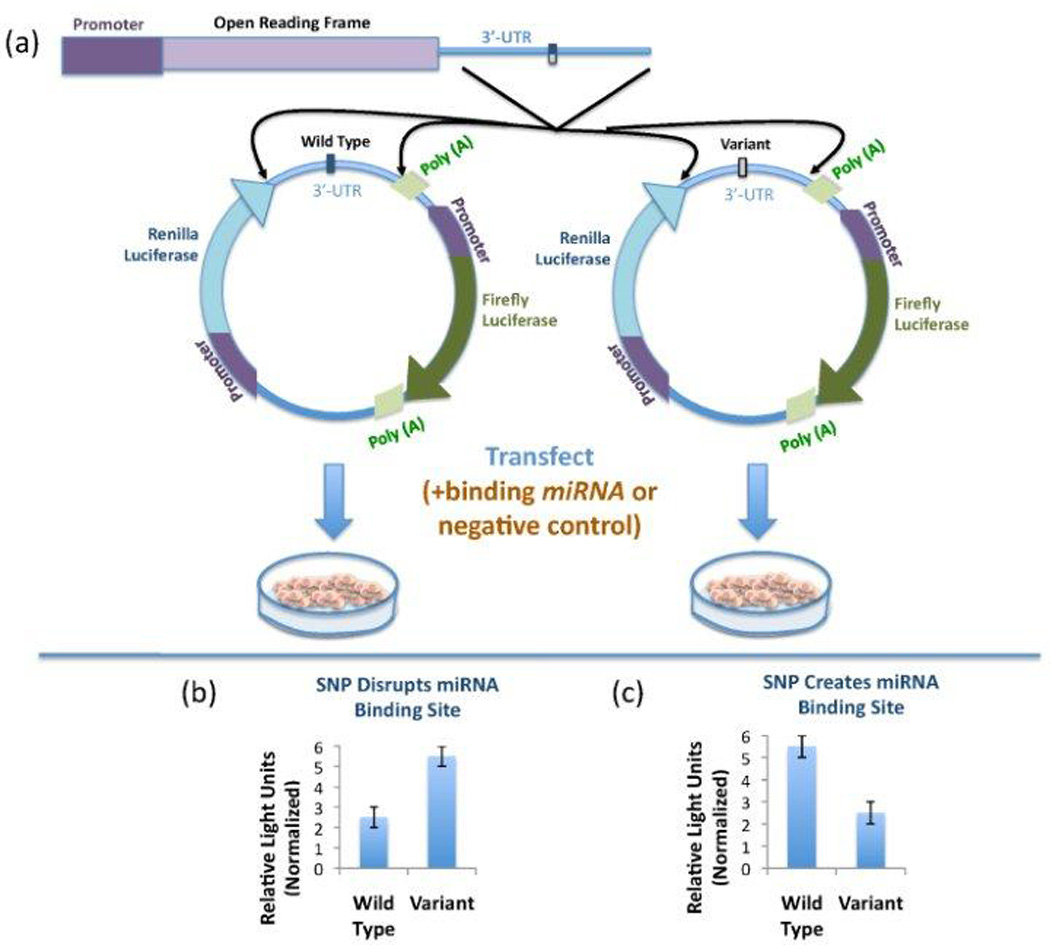

Once a suspected functional SNP has been recognized, case-control studies identify associations between the SNP and cancer risk and survival studies identify associations with outcome or response to treatment. The biological function predicted by in silico analysis can be verified in vitro using luciferase reporter assays (Figure 1). This can also be done by quantitating endogenous mRNA transcripts or protein expression within cell lines or tumor tissue that contain either the wild type or variant allele.

FIGURE 1. Schematic of the luciferase reporter assay.

(a) The 3'-UTR of the gene of interest is cloned downstream of the Renilla luciferase gene. Therefore, the effect of a SNP in the 3'-UTR will be observed via Renilla luciferase expression, as measured by a luminometer. The Firefly luciferase gene, which allows for normalization, can either be present in the same reporter construct (as pictured) or co-transfected with the reporter construct. The suspected miRNA or a negative control miRNA may also be co-transfected to test the specificity of the binding miRNA. (b) If the variant allele disrupts a miRNA binding site such that the miRNA can no longer suppress Renilla luciferase expression, the variant construct will have a higher luciferase value than the WT construct. (c) If the variant allele creates a novel miRNA binding site, Renilla luciferase expression will be suppressed by the binding miRNA.

Over the past few years, the search for this new genre of biomarkers has accelerated. SNPs within miRNA binding sites have been found to be associated with Parkinson's Disease,15 rheumatoid arthritis,16 systemic lupus erythematosus,17 Crohn's Disease,18 and psoriasis,19 among others. Yu et al20 were one of the first groups to investigate cancer-associated SNPs within miRNA binding sites. They conducted a genome-wide search for SNPs within putative miRNA binding sites based on seed region complementarity, and then identified those SNPs with cancer-associated aberrant allele frequencies. They verified this by sequencing DNA from a cohort of tumor tissue specimens of various cancers compared to control tissues. Using this method they identified 12 SNPs with aberrant allele frequencies in human tumor tissues. Since that time, many more SNPs within miRNA binding sites have been found to be associated with almost all types of human cancers.

We will review the current research on functional SNPs within miRNA binding sites identified as cancer biomarkers, starting with one of the first discovered and most extensively studied SNPs, the KRAS variant.

III. The KRAS Variant

A. The KRAS Variant and Cancer Risk

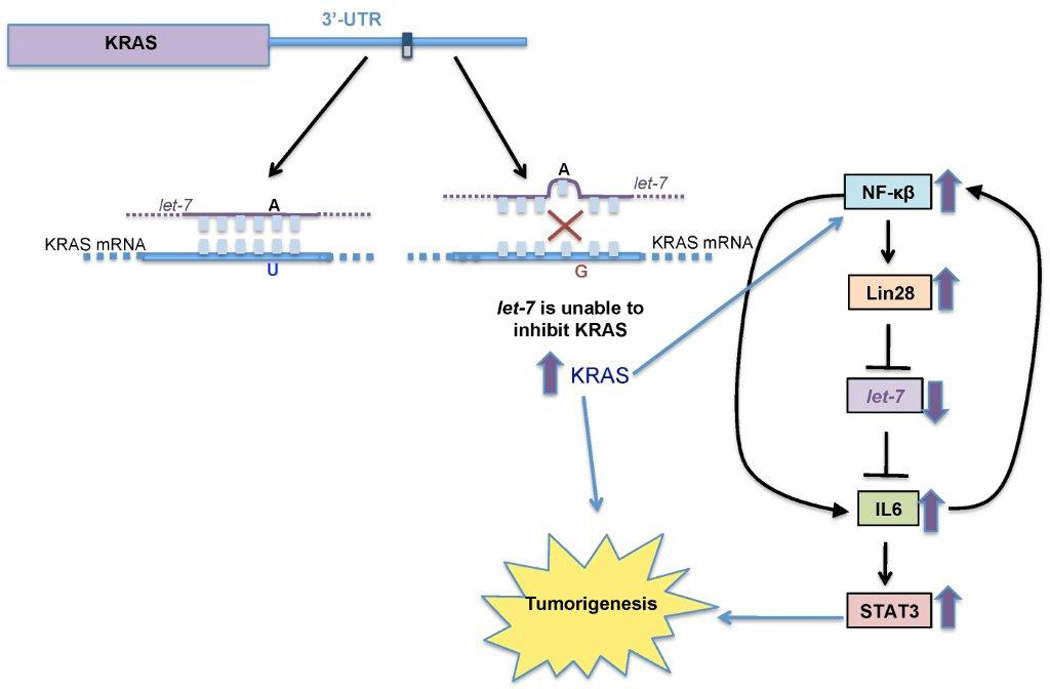

One of the first discovered miRNAs, let-7, binds to the KRAS 3'-UTR and suppresses KRAS, inhibiting cell growth.21–23 As such, let-7 acts as a tumor suppressor, and decreased expression of let-7 has been described in many cancers.24 Chin et al25 conducted the first study to identify SNPs that could modify let-7 binding using a group of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. They sequenced all of the let-7 complementary sites (LCSs) within the KRAS 3'-UTRs of these patients. One SNP (rs61764370) within LCS6, referred to as the KRAS variant, was found to be disproportionately enriched in NSCLC patients (present in 18–20%) compared to control populations (only 6%). Chin and colleagues25 further verified the association of the KRAS variant via two case-control studies. In particular, they found the variant was associated with increased risk for NSCLC among moderate smokers. The variant was not, however, found to be prognostic as there was no association with NSCLC survival.26 Furthermore, the presence of this KRAS variant has been shown to be independent of KRAS coding sequence mutations.27 The variant 'G' allele (as compared to the wild type 'T' allele) disrupts let-7 binding, and thus prevents KRAS suppression, leading to higher KRAS levels. It also induces lower let-7 levels via a still undefined mechanism.25 Studies have suggested that KRAS over-expression, can lead to induction of Lin-28, a negative regulator of let-7, potentially explaining these observations.28 (Figure 2)

FIGURE 2. The KRAS Variant and Tumorigenesis.

The SNP rs61764370 is located within the 3'-UTR of KRAS in the binding site of the miRNA let-7. The variant allele (G) disrupts let-7 binding to the mRNA transcript and prevents let-7 mediated suppression, resulting in increased KRAS protein expression. By a still undefined mechanism, the variant allele is also associated with decreased let-7 levels.25 It is hypothesized that KRAS may induce Lin-28, a negative regulator of let-7. Both increased KRAS and decreased let-7 are associated with tumorigenesis. Let-7 is involved in a feedback loop such that low let-7 induces IL-6 expression, which activates the transcription factor STAT3, leading to tumorigenesis.27

Ratner et al.29 found that the KRAS variant was also associated with increased risk for developing epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). This was consistent between three independent cohorts and two case-control studies. In particular, the KRAS variant was present in 61% of patients with a hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) history who were previously genetically uninformative (BRCA1/2 negative), suggesting that the variant may be a new independent cancer risk biomarker for HBOC families. In a GWAS based cohort study of sporadic ovarian cancer, Pharoah et al30 did not find a risk of EOC, although their cohort was very diverse and contained no HBOC cohorts. This example illustrates a recurring issue with miRNA binding site SNPs: that studies based on different patient populations can lead to conflicting results. These contradictions likely stem from the fact that the effects of SNPs within miRNA binding sites depend on the miRNA environment within a cell, or they are “context dependent”MiRNAs are dynamically regulated in response to stimulants and stressors, thereby making the impact of these variations all the more complex. Of note, a recent study by Pilarski et al31 showed that the KRAS variant was particularly enriched among uninformative (BRCA1/2 negative) patients with personal histories of both breast and ovarian cancer, further validating the importance of the KRAS variant as a genetic marker for HBOC families.

The KRAS variant has also been found to be associated with triple negative breast cancer, specifically for pre-menopausal women.32 Patients with the KRAS variant have triple negative tumors with distinct gene expression patterns compared to other triple negative breast cancer patients, suggesting that such variants may also be a way to subclassify tumors into biologically relevant subgroups. Another study done by Cerne et al33 on a breast cancer case control of only post-menopausal patients found that, among postmenopausal women with a history of hormone replacement therapy, the KRAS variant was associated with HER2-positive tumors and tumors of higher histopathologic grade. This association can also be considered prognostic, since both of these characteristics are indicative of worse prognosis. There have been several instances, thus far, identifying the KRAS variant as a prognostic or predictive marker, as discussed more below.

B. The KRAS Variant as a Prognostic and Predictive Marker

The first such study showing that the KRAS variant is a prognostic marker was a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) case-control study,34 which found that although the variant was not associated with overall risk for developing HNSCC, it was associated with significantly reduced survival. This effect was greatest in cases of oral cavity carcinomas. Another study35 examining the role of the variant and ovarian cancer outcome found reduced overall survival among postmenopausal women carrying the variant. This study further showed that ovarian cancer patients were platinum resistant, meaning they did not respond to platinum chemotherapy, which is the primary agent used to treat ovarian cancer, and which likely explains the worse outcome. These findings could help explain why some case controls with longer patient accrual times, such as GWAS based cohorts, may miss the association of the KRAS variant with cancer risk, as patients with the variant are more likely to die of their disease before recruitment.

Graziano and colleagues36 studied metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, some of whom also harbored KRAS protein-coding mutations, treated with cetuximab and irinotecan. They found that patients with the KRAS variant had poorer overall and progression free survival whether or not they were also KRAS mutant (KRAS protein-coding mutation positive). On the other hand, a follow-up study found that among metastatic CRC patients without KRAS protein-coding mutations, those with the KRAS variant had better response to cetuximab monotherapy.37 These two studies suggest that the KRAS protein-coding mutation status may determine the effects of the KRAS variant on response to treatment, and the combination of treatment is likely to impact this effect.

When examining the impact of the variant on CRC prognosis, Smits et al.38 found that the effect appeared to be stage-dependent, possibly reflecting inherent biological differences. Patients diagnosed with early stage cancer with the KRAS variant, who had no adjuvant treatment, had improved survival over those without the variant. Furthermore, harboring KRAS or BRAF protein-coding mutations enhanced this effect. KRAS overexpression due to the KRAS variant in combination with genetic alterations in genes in the Ras pathway may induce tumor senescence, explaining this effect. In contrast, a later study39 found that the KRAS variant was associated with reduced mortality in late stage colon cancer. The difference in these two results may be explained by the differences in KRAS protein-coding mutation frequency. In the second study, there were a higher percentage of KRAS coding sequence mutations among the later stage cancers than the earlier stage cancers. It may be that the KRAS variant is protective when coupled with a KRAS protein-coding mutation. In addition, the population of the first study generally did not receive treatment, in contrast to the second study. Thus, this could also reflect a possible role for the KRAS variant in treatment response, for which further studies are needed. All of these conflicting results add credence to the idea that the effects of miRNA binding SNPs are context dependent.

IV. SNPs in miRNA Binding Sites as Cancer Risk Biomarkers

Most miRNA binding site SNP studies to date have followed the case-control study design, and so the majority of our knowledge, thus far, centers on cancer risk. Following is a review of those miRNA binding site SNPs (other than the KRAS variant) that are cancer risk biomarkers.

A. Breast Cancer Risk

A number of studies have found associations between SNPs in miRNA binding sites and breast cancer risk. Tchatchou et al40 identified 11 SNPs within predicted miRNA binding sites located in the 3'-UTRs of genes involved in breast cancer and analyzed their impact in a case-control study of high-risk familial breast cancer patients. They found that a SNP within the estrogen receptor α gene (ESR1) disrupted miR-453 binding, and the variant allele was associated with increased estrogen receptor expression and breast cancer risk. Nicoloso et al41 used a general approach, first identifying all SNPs within miRNA binding sites whose variant allele was calculated to affect the minimum free energy, or stability, of the transcript by at least 8% compared to the wild type allele. They then tested these SNPs within a breast cancer case-control study and found two SNPs associated with the breast cancer patients: rs799917 within the BRCA1 coding region whose variant allele strengthens miR-638 binding and rs334348 within the TGFBR1 3'-UTR whose variant allele strengthens miR-628-5p binding. The effects of both of these SNPs were validated via luciferase reporters and by measuring endogenous protein expression. Other studies have identified SNPs in SET842 associated with increased risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women, and in ATF143 associated with increased risk of breast or ovarian cancer among carriers of BRCA2 mutations.

Pelletier et al44 focused on the BRCA1 gene, since BRCA1 coding sequence mutations are well known to associate with familial breast cancer. They identified the rs8176318 SNP, whose variant allele is associated with triple negative breast cancer, particularly among African Americans. Pongsavee et al45 had previously identified this same SNP among a Thai breast cancer population. Luciferase reporters revealed that the risk allele induced decreased BRCA1 expression, phenocopying BRCA1 coding sequence mutations.45 This approach of searching for a miRNA binding SNPs that will have a similar phenotype to a previously-known protein coding mutation is an effective method for identifying new functional variants.

B. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Risk

Two insertion/deletion polymorphisms have been associated with HCC risk. Gao et al46 identified rs3783553 in the 3'-UTR of interleukin-1α (IL1A). The variant (deletion) allele creates new binding sites for both miR-122 and miR-378, suppressing IL1A expression, and thereby attenuating the anti-tumor immunity of the IL1A cytokine and conferring HCC risk. Chen et al47 identified a different insertion/deletion polymorphism in the 3'-UTR of β-transducin repeat-containing protein (βTrCP). The 9 base pair insertion disrupts miR-920 binding and is associated with HCC risk in a Chinese case-control study. It is hypothesized that the increased βTrCP expression results in translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus where it activates antiapoptotic genes important for cell survival.

C. Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Risk

Landi et al48 selected SNPs within putative miRNA binding sites of genes known to be involved in CRC. The eight top ranking candidate SNPs were further evaluated in a CRC case-control study from the Czech Republic, one of the countries with the highest incidence of CRC. Two polymorphisms (rs17281995 in CD86 and rs1051690 in INSR) were associated with increased CRC risk. A second study using a case-control cohort from Spain found a significant association between the INSR SNP, but only a weak association for the CD86 SNP.49 Naccarati et al50 searched the 3'-UTRs of genes involved in DNA repair pathways for SNPs that affect putative miRNA binding sites and also tested them in a Czech Republic case-control study. They identified SNPs within RPA2 and GTF2H1 associated with rectal cancer risk in particular. Of note, these SNPs only lie within predicted miRNAs binding sites. Their biological function has not been validated by in vitro or in vivo studies.

D. Lung Cancer Risk

Xiong et al51 used an in silico approach to identify SNPs within the 3'-UTRs of genes involved in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and investigated their impact on a Chinese SCLC case-control study. The variant allele of the SNP within the L-MYC gene, MYCL1, associated with increased risk. Luciferase reporter assays indicated that the variant allele disrupts miR-1827 binding and suppresses MYCL1 expression. Yang et al52 identified a different functional polymorphism in the 3'-UTR of the NBS1 gene that was found to be associated with lung cancer in two independent Chinese case-control studies. The variant or risk allele was shown to allow for miR-629 binding and suppress NBS1 expression. This was validated via luciferase reporters as well as endogenous mRNA and protein expression in tumor tissues. Furthermore, they showed that X-Ray radiation induced more chromatid breaks in lymphocyte cells carrying the homozygous variant genotype, consistent with increased cancer risk.

While still the minority, more and more miRNA binding site studies are focusing on cancer prognosis and response to treatment, as compared to simply cancer risk. Investigators in the field are realizing this is where the genetic information will have the greatest clinical utility.

V. SNPs in miRNA Binding Sites as Prognostic Biomarkers

A. Breast and Ovarian Cancer Prognosis

Brendle et al53 were the first to identify a miRNA binding SNP as a breast cancer prognostic biomarker. The SNP, within the 3'-UTR of integrin beta-4 (ITGB4), lies within a putative miR-34a binding site. The variant allele is associated with poor survival and aggressive tumor characteristics, including lymph node metastasis, high grade and high stage. Zhang et al54 identified another prognostic SNP within the ryanodine receptor 3 (RYR3), a calcium channel necessary for breast cancer cell growth, morphology, migration, and adhesion. That variant allele disrupts miR-367 binding and is associated with poor progression free survival.

Wynendaele et al55 identified rs34091 within the 3'-UTR of the MDM4 gene, which creates a putative binding site for miR-191. The variant allele suppresses MDM4 expression and is associated with delayed ovarian cancer progression and decreased tumor-related death. It is suspected that overexpression of MDM4 promotes tumorigenesis by decreasing p53 function, and therefore suppressed MDM4 is protective.

B. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prognosis

Guo et al56 identified the first SNP associated with HCC outcome. They found that carriers of the variant allele in the SET8 3'-UTR had dramatically improved survival. Immunostaining of patient tissues revealed that those patients harboring the variant allele had decreased SET8 protein levels, consistent with their perfect seed region complementarity for miR-502. Depletion of SET8 activates the proapoptotic and checkpoint functions of p53, inducing a protective effect. This is the same SNP that Song et al42 identified as conferring increased risk of breast cancer, and was one of initial cancer associated SNPs discovered by Yu et al20, further supporting its significance.

C. Bladder Cancer Prognosis

Luo et al57 identified the first prognostic miRNA binding SNP for bladder cancer in the 3'-UTR of the HOXB5 gene associated with risk of high grade and high stage bladder cancer. HOXB5 is over-expressed in bladder cancer tissues and promotes cell proliferation and migration in bladder cancer cells. The SNP lies within a miR-7 binding site and luciferase reporters showed that the variant allele disrupts miR-7 binding leading to increased HOXB5 expression. This was confirmed by mRNA levels in bladder cancer tissues and cell lines with and without the variant allele.

VI. SNPs in miRNA Binding Sites as Predictive Biomarkers

A. Bladder Cancer and Response to Radiotherapy

Teo et al58 identified the first miRNA binding site SNP associated with radiotherapy outcomes. They started out by searching common SNPs within the 3'-UTRs of 20 DNA repair genes with the hypothesis that SNPs influencing DNA repair capacity may influence cancer risk and radiotherapy sensitivity. The seven candidate SNPs which showed the greatest allele specific differential for miRNA binding were tested in a cohort of muscle-invasive bladder cancer cases treated with radical radiotherapy. Carriers of the variant allele of a SNP in RAD51 had improved 5-year cancer-specific survival in the radiotherapy-treated group. It is predicted that miR-197 binds more strongly to the variant allele, reducing RAD51 expression and the tumor's ability to repair DNA damage and resist radiotherapy.

B. Prostate Cancer and Response to Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT)

Bao et al59 showed that miRNA binding site SNPs have the potential to predict response to therapy in prostate cancer. They evaluated SNPs within miRNA binding sites within a cohort of advanced prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). They identified SNPs significantly associated with disease progression (KIF3C, CDON, IFI30), prostate cancer specific mortality (KIF3C, PALLD, GABRA1), and all cause mortality (SYT9). They also found that patients with a greater number of unfavorable genotypes had a shorter time to progression and worse prostate cancer specific survival. This demonstrated that the use of combined, in addition to individual, genotypes may strengthen the clinical utility of such SNPs.

C. Response to Methotrexate and Cisplatin

In an early study, Mishra et al60 identified a SNP within the 3'-UTR of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) that interferes with miR-24 binding. The resulting DHFR over-expression induces methotrexate resistance. This was the first instance of a miRNA binding SNP predicting response to chemotherapy. More recently, Wu et al61 identified a cisplatin sensitivity marker. The SNP in the 3'-UTR of AP-2α, disrupts a miR-200b/200c/429 family binding site, leading to increased levels of AP-2αwhich is known to enhance cisplatin-induced apoptosis. They found that the variant allele induced sensitivity to cisplatin using clonogenic assays. Neither of these SNPs, however, have been tested in patient populations.

VI. CONCLUSION

Over the past five years, there has been a rapid expansion in the search for SNPs within miRNA binding sites, a novel genre of cancer biomarkers. We have seen that these SNPs can play significant roles in carcinogenesis, prognosis and response to treatment. To date, most research has identified biomarkers of cancer risk via case-control study designs. The ability to identify those individuals most at risk to develop cancer is invaluable, particularly among members of high-risk families, as it allows us to take early preventative action. However, the greatest clinical application will likely lie with prognostic and predictive biomarkers, and this is the direction the field is moving. It is here that we will use this vast amount of genetic information to make better clinical decisions and more effectively treat individual patients.

Coding the sequence of tumor acquired mutations that are already known to affect prognosis and response to therapy provides a starting point to identify miRNA binding SNPs that may have similar intracellular effects and clinical results. Currently, patients harboring these variants are only tested for the known coding sequence mutations and are therefore misidentified, potentially receiving inferior treatments. Perhaps the most efficient and effective method of identifying clinically-useful SNPs will be to identify those SNPs that affect response to a particular type of treatment, such as those studies on methotrexate and cisplatin response.

That being said, we have seen that even small differences in cellular environments can significantly influence the effects of miRNA binding site SNPs, and so flushing out the best treatment for the patients that harbor them is more complex. The miRNA environment is dynamically regulated, responding to stressors and stimulants within a cell, as well as external factors. As such, miRNA binding site SNPs are not fixed mutations, they are dependent on the miRNAs expressed. The impact of these SNPs is complex and it will not be clarified by studies of large populations, such as with GWAS cohorts, but instead by clinically well characterized populations, such as those found in clinical trials. Once we figure out how to harness this new genre of genetic information, it has great potential to provide us with better insight into tumor biology, and ultimately to help us to better treat cancer patients, leading to improvements in survival.

TABLE 1.

SNPs within miRNA Binding Sites as Biomarkers of Cancer Risk, Prognosis, and Response to Therapy organized by cancer type. This table includes a more complete list of those SNPs identified to date, including some not discussed in the text.

| Cancer Type | Gene | SNP WT-->Variant Allele |

miRNA | Clinical Association with Variant Allele |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder Cancer | HOXB5 | rs1010 A-->G |

miR-7 | high grade and high stage bladder cancer | Luo, 201257 |

| PARP1 | rs8679 T-->C |

miR-145, miR-105, miR-630, miR-302a | increased bladder cancer risk | Teo, 201258 | |

| RAD51 | rs7180135 A-->G |

miR-197 | improved cancer-specific survival following radiotherapy | Teo, 201258 | |

| Breast Cancer | ATF1 | rs11169571 T-->C |

miR-138 | increased risk of breast or ovarian cancer among BRCA2 mutation carriers | Kontorovich, 201043 |

| BRCA1 | rs799917 T-->A/C |

miR-638 | increased breast cancer risk | Nicoloso, 201041 | |

| BRCA1 | rs8176318 G-->T |

unknown | increased breast cancer risk, particularly triple negative breast cancer and high stage disease | Pelletier, 201144; Pongsavee, 200944 | |

| ESR1 | rs2747648 T-->C |

miR-453 | increased breast cancer risk | Tchatchou, 200940 | |

| ITGB4 | rs743554 G-->A |

miR-34a | poor survival, high grade, high stage, lymph node metastasis | Brendle, 200853 | |

| KRAS | rs61764370 G-->T |

let-7 | increased risk of triple negative breast cancer, associated with HBOC, HER2 positive and high grade tumors in postmenopausal women on HRT | Paranjape, 201131; Pilarski, 201232; Cerne33 | |

| RYR3 | rs1044129 A-->G |

miR-367 | poor progression free survival | Zhang, 201154 | |

| SET8 | rs16917496 T-->C |

miR-502 | increased breast cancer risk, premenopausal women | Song, 200942 | |

| TGFBR1 | rs334348 G-->A |

miR-628-5p | increased breast cancer risk | Nicoloso, 201041 | |

| Cervical Cancer | BCL2 | rs49878756 C-->T |

miR-195 | increased cervical cancer risk | Reshmi, 201162 |

| LAMB3 | rs2566 C-->T |

miR-218 | increased cervical cancer risk | Zhou, 201063 | |

| Colorectal Cancer | CD86 | rs17281995 G-->C |

miR-337, miR-582, miR-200a*, miR-184, miR-212 | increased CRC risk, not confirmed in second study | Landi, 200848; Landi, 201149 |

| GTF2H1 | rs4596 G-->C |

miR-518a-5p, miR-527, miR-1205 | increased rectal cancer risk | Naccarati, 201250 | |

| KRAS | rs61764370 G-->T |

let-7 | poorer response to cetuximab and irinotecan, improved survival when combined with KRAS coding mutation | Graziano, 201036, Zhang, 201137, Smits, 201138, Ryan, 201239 | |

| INSR | rs1051690 G-->A |

miR-612 | increased CRC risk | Landi, 200848; Landi, 201149 | |

| RPA2 | rs7356 A-->G |

miR-3149, miR-1183 | increased rectal cancer risk | Naccarati, 201250 | |

| Head and Neck Cancer | KRAS | rs61764370 G-->T |

let-7 | reduced survival for HNSCC | Christensen, 200934 |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | βTrCP | rs16405 9bp del-->ins |

miR-920 | increased HCC risk | Chen, 201047 |

| IL1A | rs3783553 TTCA ins-->del |

miR-122, miR-378 | increased HCC risk | Gao, 200946 | |

| SET8 | rs16917496 T-->C |

miR-502 | improved HCC survival | Guo, 201156 | |

| Lung Cancer | KRAS | rs61764370 G-->T |

let-7 | increased risk of NSCLC among moderate smokers, no association with outcome | Chin, 200825; Nelson, 201028 |

| MYCL1 | rs3134615 G-->T |

miR-1827 | increased SCLC risk | Xiong, 201151 | |

| NBS1 | rs2735383 G-->C |

miR-629 | increased lung cancer risk | Yang, 201252 | |

| Ovarian Cancer | KRAS | rs61764370 G-->T |

let-7 | potential increased risk of EOC and reduced overall survival for postmenopausal women | Ratner, 201029, Pharoah, 201130, Ratner, 201135 |

| MDM4 | rs34091 C-->A |

miR-191 | delayed ovarian cancer progression and tumor related death | Wynendaele, 201055 | |

| Prostate Cancer | BMPR1B | rs1434536 C-->T |

miR-125b | increased risk of localized disease for men>70yo | Feng, 201264 |

| CDON | rs3737336 T-->C |

*miR-181 | decreased risk disease progression | Bao, 201159 | |

| GABRA1 | rs998754 T-->G |

*miR-600 | increased prostate cancer specific mortality | Bao, 201159 | |

| IFI30 | rs1045747 C-->T |

*miR-29, *miR-767-5p | decreased risk disease progression | Bao, 201159 | |

| KIF3C | rs6728684 T-->G |

*miR-505 | increased disease progression and prostate cancer specific mortality | Bao, 201159 | |

| PALLD | rs1071738 C-->G |

*miR-182, *miR-3128 | decreased risk prostate cancer specific mortality | Bao, 201159 | |

| SYT9 | rs4351800 A-->C |

*miR-4277 | increased all cause mortality | Bao, 201159 |

Predicted miRNAs using MicroSNiPer10 (http://cbdb.nimh.nih.gov/microsniper/index.php) if specific miRNAs were not mentioned within reference article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Weidhaas is supported by a grant from the NCI (R01CA157749).

Abbreviations

- 3'-UTR

3'-untranslated region

- ADT

androgen-deprivation therapy

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- EOC

epithelial ovarian cancer

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- HBOC

hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- miRNA

microRNA

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, Walenz BP, Axelrod N, Huang J, Kirkness EF, Denisov G, Lin Y, MacDonald JR, Pang AW, Shago M, Stockwell TB, Tsiamouri A, Bafna V, Bansal V, Kravitz SA, Busam DA, Beeson KY, McIntosh TC, Remington KA, Abril JF, Gill J, Borman J, Rogers YH, Frazier ME, Scherer SW, Strausberg RL, Venter JC. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, Aharonov R, Gilad S, Barad O, Barzilai A, Einat P, Einav U, Meiri E, Sharon E, Spector Y, Bentwich Z. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2005;37:766–770. doi: 10.1038/ng1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold M, Ellwanger DC, Hartsperger ML, Pfeufer A, Stumpflen V. Cis-acting polymorphisms affect complex traits through modifications of microRNA regulation pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen K, Rajewsky N. Natural selection on human microRNA binding sites inferred from SNP data. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1452–1456. doi: 10.1038/ng1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barenboim M, Zoltick BJ, Guo Y, Weinberger DR. MicroSNiPer: a web tool for prediction of SNP effects on putative microRNA targets. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1223–1232. doi: 10.1002/humu.21349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziebarth JD, Bhattacharya A, Chen A, Cui Y. PolymiRTS Database 2.0: linking polymorphisms in microRNA target sites with human diseases and complex traits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D216–D221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004;10:1507–1517. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang G, van der Walt JM, Mayhew G, Li YJ, Zuchner S, Scott WK, Martin ER, Vance JM. Variation in the miRNA-433 binding site of FGF20 confers risk for Parkinson disease by overexpression of alpha-synuclein. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatzikyriakidou A, Voulgari PV, Georgiou I, Drosos AA. A polymorphism in the 3'-UTR of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK1), a target gene of miR-146a, is associated with rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:411–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consiglio CR, Veit TD, Monticielo OA, Mucenic T, Xavier RM, Brenol JC, Chies JA. Association of the HLA-G gene +3142C>G polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 2011;77:540–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brest P, Lapaquette P, Souidi M, Lebrigand K, Cesaro A, Vouret-Craviari V, Mari B, Barbry P, Mosnier JF, Hebuterne X, Harel-Bellan A, Mograbi B, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Hofman P. A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xenophagy in Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:242–245. doi: 10.1038/ng.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu LS, Li FF, Sun LD, Li D, Su J, Kuang YH, Chen G, Chen XP, Chen X. A miRNA-492 binding-site polymorphism in BSG (basigin) confers risk to psoriasis in central south Chinese population. Hum Genet. 2011;130:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Z, Li Z, Jolicoeur N, Zhang L, Fortin Y, Wang E, Wu M, Shen SH. Aberrant allele frequencies of the SNPs located in microRNA target sites are potentially associated with human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4535–4541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esquela-Kerscher A, Trang P, Wiggins JF, Patrawala L, Cheng A, Ford L, Weidhaas JB, Brown D, Bader AG, Slack FJ. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:759–764. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, Sharp PA, Jacks T. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Osada H, Endoh H, Harano T, Yatabe Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jerome T, Laurie P, Louis B, Pierre C. Enjoy the Silence: The Story of let-7 MicroRNA and Cancer. Curr Genomics. 2007;8:229–233. doi: 10.2174/138920207781386933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chin LJ, Ratner E, Leng S, Zhai R, Nallur S, Babar I, Muller RU, Straka E, Su L, Burki EA, Crowell RE, Patel R, Kulkarni T, Homer R, Zelterman D, Kidd KK, Zhu Y, Christiani DC, Belinsky SA, Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB. A SNP in a let-7 microRNA complementary site in the KRAS 3' untranslated region increases non-small cell lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8535–8540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson HH, Christensen BC, Plaza SL, Wiencke JK, Marsit CJ, Kelsey KT. KRAS mutation, KRAS-LCS6 polymorphism, and non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;69:51–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kundu ST, Nallur S, Paranjape T, Boeke M, Weidhaas JB, Slack FJ. KRAS alleles: the LCS6 3'UTR variant and KRAS coding sequence mutations in the NCI-60 panel. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:361–366. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.18794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell. 2009;139:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratner E, Lu L, Boeke M, Barnett R, Nallur S, Chin LJ, Pelletier C, Blitzblau R, Tassi R, Paranjape T, Hui P, Godwin AK, Yu H, Risch H, Rutherford T, Schwartz P, Santin A, Matloff E, Zelterman D, Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB. A KRAS-variant in ovarian cancer acts as a genetic marker of cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6509–6515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pharoah PD, Palmieri RT, Ramus SJ, Gayther SA, Andrulis IL, Anton-Culver H, Antonenkova N, Antoniou AC, Goldgar D, Beattie MS, Beckmann MW, Birrer MJ, Bogdanova N, Bolton KL, Brewster W, Brooks-Wilson A, Brown R, Butzow R, Caldes T, Caligo MA, Campbell I, Chang-Claude J, Chen YA, Cook LS, Couch FJ, Cramer DW, Cunningham JM, Despierre E, Doherty JA, Dork T, Durst M, Eccles DM, Ekici AB, Easton D, Fasching PA, de Fazio A, Fenstermacher DA, Flanagan JM, Fridley BL, Friedman E, Gao B, Sinilnikova O, Gentry-Maharaj A, Godwin AK, Goode EL, Goodman MT, Gross J, Hansen TV, Harnett P, Rookus M, Heikkinen T, Hein R, Hogdall C, Hogdall E, Iversen ES, Jakubowska A, Johnatty SE, Karlan BY, Kauff ND, Kaye SB, Chenevix-Trench G, Kelemen LE, Kiemeney LA, Kjaer SK, Lambrechts D, Lapolla JP, Lazaro C, Le ND, Leminen A, Leunen K, Levine DA, Lu Y, Lundvall L, Macgregor S, Marees T, Massuger LF, McLaughlin JR, Menon U, Montagna M, Moysich KB, Narod SA, Nathanson KL, Nedergaard L, Ness RB, Nevanlinna H, Nickels S, Osorio A, Paul J, Pearce CL, Phelan CM, Pike MC, Radice P, Rossing MA, Schildkraut JM, Sellers TA, Singer CF, Song H, Stram DO, Sutphen R, Lindblom A, Terry KL, Tsai YY, van Altena AM, Vergote I, Vierkant RA, Vitonis AF, Walsh C, Wang-Gohrke S, Wappenschmidt B, Wu AH, Ziogas A, Berchuck A, Risch HA. The role of KRAS rs61764370 in invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for clinical testing. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3742–3750. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilarski R, Patel DA, Weitzel J, McVeigh T, Dorairaj JJ, Heneghan HM, Miller N, Weidhaas JB, Kerin MJ, McKenna M, Wu X, Hildebrandt M, Zelterman D, Sand S, Shulman LP. The KRAS-Variant Is Associated with Risk of Developing Double Primary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paranjape T, Heneghan H, Lindner R, Keane FK, Hoffman A, Hollestelle A, Dorairaj J, Geyda K, Pelletier C, Nallur S, Martens JW, Hooning MJ, Kerin M, Zelterman D, Zhu Y, Tuck D, Harris L, Miller N, Slack F, Weidhaas J. A 3'-untranslated region KRAS variant and triple-negative breast cancer: a case-control and genetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:377–386. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70044-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerne JZ, Stegel V, Gersak K, Novakovic S. KRAS rs61764370 is associated with HER2-overexpressed and poorly-differentiated breast cancer in hormone replacement therapy users: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:105–112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen BC, Moyer BJ, Avissar M, Ouellet LG, Plaza SL, McClean MD, Marsit CJ, Kelsey KT. A let-7 microRNA-binding site polymorphism in the KRAS 3' UTR is associated with reduced survival in oral cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1003–1007. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratner ES, Keane FK, Lindner R, Tassi RA, Paranjape T, Glasgow M, Nallur S, Deng Y, Lu L, Steele L, Sand S, Muller RU, Bignotti E, Bellone S, Boeke M, Yao X, Pecorelli S, Ravaggi A, Katsaros D, Zelterman D, Cristea MC, Yu H, Rutherford TJ, Weitzel JN, Neuhausen SL, Schwartz PE, Slack FJ, Santin AD, Weidhaas JB. A KRAS variant is a biomarker of poor outcome, platinum chemotherapy resistance and a potential target for therapy in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2011;2011:539–547. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graziano F, Canestrari E, Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Galluccio N, Santini D, Rocchi M, Vincenzi B, Salvatore L, Cremolini C, Spoto C, Catalano V, D'Emidio S, Giordani P, Tonini G, Falcone A, Magnani M. Genetic modulation of the Let-7 microRNA binding to KRAS 3'-untranslated region and survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with salvage cetuximab-irinotecan. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:458–464. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Winder T, Ning Y, Pohl A, Yang D, Kahn M, Lurje G, Labonte MJ, Wilson PM, Gordon MA, Hu-Lieskovan S, Mauro DJ, Langer C, Rowinsky EK, Lenz HJ. A let-7 microRNA-binding site polymorphism in 3'-untranslated region of KRAS gene predicts response in wild-type KRAS patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab monotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:104–109. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smits KM, Paranjape T, Nallur S, Wouters KA, Weijenberg MP, Schouten LJ, van den Brandt PA, Bosman FT, Weidhaas JB, van Engeland M. A let-7 microRNA SNP in the KRAS 3'UTR is prognostic in early-stage colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7723–7731. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. KRAS-LCS6 Genotype as a Prognostic Marker in Early-Stage CRC-Letter. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3487–3488. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tchatchou S, Jung A, Hemminki K, Sutter C, Wappenschmidt B, Bugert P, Weber BH, Niederacher D, Arnold N, Varon-Mateeva R, Ditsch N, Meindl A, Schmutzler RK, Bartram CR, Burwinkel B. A variant affecting a putative miRNA target site in estrogen receptor (ESR) 1 is associated with breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:59–64. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicoloso MS, Sun H, Spizzo R, Kim H, Wickramasinghe P, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Ferdin J, Kunej T, Xiao L, Manoukian S, Secreto G, Ravagnani F, Wang X, Radice P, Croce CM, Davuluri RV, Calin GA. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms inside microRNA target sites influence tumor susceptibility. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2789–2798. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song F, Zheng H, Liu B, Wei S, Dai H, Zhang L, Calin GA, Hao X, Wei Q, Zhang W, Chen K. An miR-502-binding site single-nucleotide polymorphism in the 3'-untranslated region of the SET8 gene is associated with early age of breast cancer onset. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6292–6300. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kontorovich T, Levy A, Korostishevsky M, Nir U, Friedman E. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNA binding sites and miRNA genes as breast/ovarian cancer risk modifiers in Jewish high-risk women. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:589–597. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelletier C, Speed WC, Paranjape T, Keane K, Blitzblau R, Hollestelle A, Safavi K, van den Ouweland A, Zelterman D, Slack FJ, Kidd KK, Weidhaas JB. Rare BRCA1 haplotypes including 3'UTR SNPs associated with breast cancer risk. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:90–99. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pongsavee M, Yamkamon V, Dakeng S, P Oc, Smith DR, Saunders GF, Patmasiriwat P. The BRCA1 3'-UTR: 5711+421T/T_5711+1286T/T genotype is a possible breast and ovarian cancer risk factor. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:307–317. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y, He Y, Ding J, Wu K, Hu B, Liu Y, Wu Y, Guo B, Shen Y, Landi D, Landi S, Zhou Y, Liu H. An insertion/deletion polymorphism at miRNA-122-binding site in the interleukin-1alpha 3' untranslated region confers risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2064–2069. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, He Y, Ding J, Jiang Y, Jia S, Xia W, Zhao J, Lu M, Gu Z, Gao Y. An insertion/deletion polymorphism in the 3' untranslated region of beta-transducin repeat-containing protein (betaTrCP) is associated with susceptibility for hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:552–556. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landi D, Gemignani F, Naccarati A, Pardini B, Vodicka P, Vodickova L, Novotny J, Forsti A, Hemminki K, Canzian F, Landi S. Polymorphisms within micro-RNA-binding sites and risk of sporadic colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:579–584. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landi D, Moreno V, Guino E, Vodicka P, Pardini B, Naccarati A, Canzian F, Barale R, Gemignani F, Landi S. Polymorphisms affecting micro-RNA regulation and associated with the risk of dietary-related cancers: a review from the literature and new evidence for a functional role of rs17281995 (CD86) and rs1051690 (INSR), previously associated with colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 2011;717:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naccarati A, Pardini B, Stefano L, Landi D, Slyskova J, Novotny J, Levy M, Polakova V, Lipska L, Vodicka P. Polymorphisms in miRNA-binding sites of nucleotide excision repair genes and colorectal cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1346–1351. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiong F, Wu C, Chang J, Yu D, Xu B, Yuan P, Zhai K, Xu J, Tan W, Lin D. Genetic variation in an miRNA-1827 binding site in MYCL1 alters susceptibility to small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5175–5181. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang L, Li Y, Cheng M, Huang D, Zheng J, Liu B, Ling X, Li Q, Zhang X, Ji W, Zhou Y, Lu J. A functional polymorphism at microRNA-629-binding site in the 3'-untranslated region of NBS1 gene confers an increased risk of lung cancer in Southern and Eastern Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:338–347. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brendle A, Lei H, Brandt A, Johansson R, Enquist K, Henriksson R, Hemminki K, Lenner P, Forsti A. Polymorphisms in predicted microRNA-binding sites in integrin genes and breast cancer: ITGB4 as prognostic marker. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1394–1399. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Liu Y, Song F, Zheng H, Hu L, Lu H, Liu P, Hao X, Zhang W, Chen K. Functional SNP in the microRNA-367 binding site in the 3'UTR of the calcium channel ryanodine receptor gene 3 (RYR3) affects breast cancer risk and calcification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13653–13658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103360108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wynendaele J, Bohnke A, Leucci E, Nielsen SJ, Lambertz I, Hammer S, Sbrzesny N, Kubitza D, Wolf A, Gradhand E, Balschun K, Braicu I, Sehouli J, Darb-Esfahani S, Denkert C, Thomssen C, Hauptmann S, Lund A, Marine JC, Bartel F. An illegitimate microRNA target site within the 3' UTR of MDM4 affects ovarian cancer progression and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9641–9649. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo Z, Wu C, Wang X, Wang C, Zhang R, Shan B. A polymorphism at the miR-502 binding site in the 3'-untranslated region of the histone methyltransferase SET8 is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma outcome. Int J Cancer. 2011;313:1318–1322. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo J, Cai Q, Wang W, Huang H, Zeng H, He W, Deng W, Yu H, Chan E, Ng CF, Huang J, Lin T. A MicroRNA-7 Binding Site Polymorphism in HOXB5 Leads to Differential Gene Expression in Bladder Cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teo MT, Landi D, Taylor CF, Elliott F, Vaslin L, Cox DG, Hall J, Landi S, Bishop DT, Kiltie AE. The role of microRNA-binding site polymorphisms in DNA repair genes as risk factors for bladder cancer and breast cancer and their impact on radiotherapy outcomes. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:581–586. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bao BY, Pao JB, Huang CN, Pu YS, Chang TY, Lan YH, Lu TL, Lee HZ, Juang SH, Chen LM, Hsieh CJ, Huang SP. Polymorphisms inside microRNAs and microRNA target sites predict clinical outcomes in prostate cancer patients receiving androgen-deprivation therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:928–936. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Mishra PJ, Longo-Sorbello GS, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. A miR-24 microRNA binding-site polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase gene leads to methotrexate resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu Y, Xiao Y, Ding X, Zhuo Y, Ren P, Zhou C, Zhou J. A miR-200b/200c/429-binding site polymorphism in the 3' untranslated region of the AP-2alpha gene is associated with cisplatin resistance. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reshmi G, Surya R, Jissa VT, Babu PS, Preethi NR, Santhi WS, Jayaprakash PG, Pillai MR. C-T variant in a miRNA target site of BCL2 is associated with increased risk of human papilloma virus related cervical cancer--an in silico approach. Genomics. 2011;98:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou X, Chen X, Hu L, Han S, Qiang F, Wu Y, Pan L, Shen H, Li Y, Hu Z. Polymorphisms involved in the miR-218-LAMB3 pathway and susceptibility of cervical cancer, a case-control study in Chinese women. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feng N, Xu B, Tao J, Li P, Cheng G, Min Z, Mi Y, Wang M, Tong N, Tang J, Zhang Z, Wu H, Zhang W, Wang Z, Hua L. A miR-125b binding site polymorphism in bone morphogenetic protein membrane receptor type IB gene and prostate cancer risk in China. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:369–373. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]