Abstract

Multiple theories posit that people with a history of depression are at higher risk for a depressive episode than people who have never experienced depression, which may be partly due to differences in stress-reactivity. Additionally, both the dynamic model of affect and the broaden-and-build theory suggest that stress and positive affect interact to predict negative affect, but this moderation has never been tested in the context of depression history. The current study used multilevel modeling to examine these issues among 1549 college students with or without a history of depression. Students completed a 30-day online diary study in which they reported daily their perceived stress, positive affect, and negative affect (including depression, anxiety, and hostility). On days characterized by higher than usual stress, students with a history of depression reported greater decreases in positive affect and greater increases in depressed affect than students with no history. Furthermore, the relations between daily stress and both depressed and anxious affect were moderated by daily positive affect among students with remitted depression. These results indicate that students with a history of depression show greater stress-reactivity even when in remission, which may place them at greater risk for recurrence. These individuals may also benefit more from positive affect on higher stress days despite being less likely to experience positive affect on such days. The current findings have various implications both clinically and for research on stress, mood, and depression.

Keywords: depression history, stress-reactivity, positive affect, college students

Depression is characterized as a mood disorder, and as such both adults and adolescents experiencing a depressive episode report higher negative affect and lower positive affect at the daily level than those without depression (Bylsma, Taylor-Clift, & Rottenberg, 2011; Larson, Raffaelli, Richards, Ham, & Jewell, 1990; Myin-Germeys et al., 2003; Peeters, Nicolson, Berkhof, Delespaul, & deVries, 2003; Silk et al., 2011). Individuals with depression are also more emotionally stress-reactive; that is, their mood is more closely tied to the perceived stressfulness of daily events (Bylsma et al., 2011; Wichers et al., 2007a). Less is known, however, about the relation between daily stress and mood among people with remitted depression. Multiple theories suggest that these individuals, despite being clinically non-depressed, may still be more stress-reactive than those who have never experienced depression, and therefore at increased risk for later depressive symptoms and recurrence (Cohen, Gunthert, Butler, O’Neill, & Tolpin, 2005; Parrish, Cohen, & Laurenceau, 2011; Segal et al., 2006). The goal of the current study was to further understand the potential lasting ramifications of depression with regard to emotional stress-reactivity, as well as whether depression history moderates the role of positive affect in the daily stress process. These issues were examined in a large sample of college students, an at-risk group for first onset and recurrence of a depressive episode (Alloy et al., 2006; O’Grady, Tennen, & Armeli, 2010).

History of Depression: A Hidden Vulnerability

Several theories contend that people who have experienced depression differ from people with no history of depression with regard to biological, psychosocial, cognitive, and/or personality characteristics that confer risk for later depressive episodes. One category of explanations for these differences is known as “scarring” hypotheses (for a review, see Wichers, Geschwind, van Os, & Peeters, 2010). This idea asserts that depression produces lasting changes in people (i.e., a psychosocial “scar”) that, in turn, increase vulnerability for future episodes. Similarly, the priming hypothesis states that depression leaves behind latent symptoms that are awakened when individuals undergo duress, such as during times of elevated stress or dysphoria (O’Grady et al., 2010). Regardless of the exact mechanism, these theories point to depression as a cause of long-term psychological damage.

Alternatively to the scarring hypotheses, the vulnerability hypothesis asserts that people with a history of depression possess psychological and/or biological characteristics that existed before the initial onset of symptoms and confer risk for recurrent depression (for a review, see Burcusa & Iacono, 2007). For example, in a 3-year longitudinal study of college students, those who had experienced depression prior to study participation and those who experienced an initial depressive onset during the study showed greater decreases in positive affect on more stressful days compared to students with no history of depression, suggesting similar vulnerability profiles (O’Grady et al., 2010). Evidence from another longitudinal study of college freshmen showed that students with at-risk cognitive styles (e.g., perfectionism; concern with others’ approval) were more than 6 times as likely to develop first onset or recurrence of depression over the next 2.5 years than students with low-risk styles (Alloy et al., 2006). The vulnerability hypothesis, therefore, posits that depression history serves only as a marker, and not a cause, of predisposing risk factors for recurrence. However, this idea still suggests that studying individuals with remitted depression is important, as they should not systematically differ from people with current or recent depression in terms of risk factors, yet may still be overlooked when screening for mental health issues.

The Role of Positive Affect

Another way in which depression history may increase vulnerability for future depressive episodes relates to its influence on positive affect and the role of positive affect in the daily stress and coping process. Positive and negative affect are theorized to be independent and therefore may be uniquely influenced by life events (Tellegen, Watson, & Clark, 1999). Multiple studies have shown that the daily stress-negative affect relation is weakened when positive affect is high (McHugh, Kaufman, Frost, Fitzmaurice, & Weiss, 2013; Zautra, Affleck, Tennen, Reich, & Davis, 2005). These results extend to the relation between daily pain and negative affect among people with chronic pain conditions (Strand et al., 2006; Zautra, Johnson, & Davis, 2005; Zautra, Smith, Affleck, & Tennen, 2001).

One explanation for this pattern comes from the dynamic model of affect, which asserts that under threatening conditions, such as stress or pain, positive and negative affect become polarized (Zautra, Affleck et al., 2005; Zautra, Reich, Davis, Potter, & Nicolson, 2000). Affect polarization refers to a dominance of one type of affect, positive or negative, over the other, often conceptualized as a stronger negative correlation between the two during high-stress versus low-stress periods. According to this theory, polarization occurs in reaction to stress to simplify affective processing, thereby hastening decision making in order to adapt to the threat. The broaden-and-build theory predicts a similar pattern but alternatively contends that positive emotions allow for cognitive flexibility (Fredrickson, 2001). When positive affect remains high during stressful situations, people are better equipped to cope, thereby mitigating increases in negative affect and preserving well-being (Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Zautra, Johnson et al., 2005). In fact, stronger positive affect buffering of stress has been associated with a lower risk of lifetime major depression (Wichers et al., 2007b). Although both theories make complementary predictions regarding interactions between stress and mood, a notable distinction is that the dynamic model of affect emphasizes the transient relations between stress and positive affect relatively more than the broaden-and-build theory, which conceptualizes positive affect as a long-term resource underlying resiliency. Neither theory, however, has been examined in the context of depression history.

Evidence does suggest that individuals with a history of depression may reap the greatest benefit from positive affect. For example, the negative relation between positive affect and depressive symptoms has been shown to be stronger when people are under stress (Pruchno & Meeks, 2004). Furthermore, positive affect variability (operationalized as the standard deviation in positive affect across time) is associated with increased depression/anxiety and decreased happiness (Gruber, Kogan, Quoidbach, & Mauss, 2013). Together, these studies suggest that people with a history of depression, who have been shown to be more stress-reactive (Bylsma et al., 2011; O’Grady et al., 2010; Wichers et al., 2007a), may be especially vulnerable for recurrence of depression due to greater decrements and/or fluctuations in positive affect under stressful conditions. Likewise, preservation of positive affect during stress would confer the greatest protective effect for these individuals.

Micro-longitudinal Studies of Stress-reactivity and History of Depression

Micro-longitudinal or daily process designs are ideally suited to examine how individual differences (e.g., depression history) influence within-person relations between stress and affect at the level of analysis at which they unfold. These methods allow researchers to identify circumstances under which the hidden vulnerabilities associated with depression may emerge that otherwise might be obscured when examining global indicators (e.g., self-esteem; excessive reassurance-seeking) or using more traditional cross-sectional or longitudinal designs. For example, daily diary studies of people suffering from chronic pain conditions, such as arthritis or fibromyalgia, have revealed that these individuals not only report more day-to-day pain when they have a history of depression (Zautra et al., 2007), but they also experience more negative reactions to their pain (Conner et al., 2006; Tennen, Affleck, & Zautra, 2006). Additionally, adolescents with major depression show greater emotional variability (measured using ecological momentary assessment over the course of at least 1 week) than non-depressed youths (Larson et al., 1990; Silk et al., 2011).

More germane to the current report, an experience sampling study of French college students showed that men with remitted depression, but not women, experienced higher depressed affect following negative events than men with no history of depression (Husky, Mazure, Maciejewski, & Swendsen, 2009). Additionally, O’Grady et al. (2010) showed that U.S. college students with a history of depression not only reported greater decreases in positive affect on higher stress days, but were more likely to blame others for negative events that occurred on those days, a behavior indicative of maladaptive coping and poor psychological adjustment (Tennen & Affleck, 1990). These studies were able to capture contingent relations between daily events and affective reactions to those events in the lives of individuals with remitted depression. The current study used a daily diary approach similar to O’Grady et al. to examine within-person variability in college students’ emotional stress-reactivity and moderation by positive affect, as well as how these processes differ as a function of depression history.

The Current Study

This is the first study to examine depression history, emotional stress-reactivity, and positive affect in a young adult, non-clinical sample. Understanding the influence of depression history among college students, a younger sample than traditionally studied, is increasingly relevant as the average age of first onset of depression has decreased across birth cohorts (Wittchen & Uhmann, 2010). Furthermore, college can be an extremely stressful period (Robotham & Julian, 2006) that may leave students vulnerable to a depressive episode, especially if they possess a preexisting vulnerability such as greater stress-reactivity (Cohen et al., 2005). In addition, most daily diary studies of depression history have included relatively small samples. The current study, however, included over 1500 students in the final analysis, with a sizable proportion (31%) having previously experienced at least one depressive episode.

Our primary aim was to examine whether stress-reactivity differed between students with remitted depression versus those with recent depression (i.e., in the past year) or no history of depression. Because the scarring and vulnerability hypotheses both predict that people who have experienced depression will exhibit similar characteristics related to depression risk regardless of time since their last episode, we did not expect differences between students with remitted versus recent depression. However, we anticipated that both groups would exhibit stronger stress-reactivity than students with no history of depression. Such differences could indicate an important risk factor for depression recurrence that may be otherwise overlooked in mental health screenings, especially among students with remitted depression.

To provide evidence suggesting whether group differences in stress-reactivity reflect a preexisting vulnerability or a psychological scar, we examined neuroticism as a marker of depression vulnerability. Not only is neuroticism associated with increased risk for depression (Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, 2004; Klein, Kotov, & Bufferd, 2011), but this personality trait is linked to greater stress-reactivity (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Gunthert, Cohen, & Armeli, 1999; Suls & Martin, 2005; Zautra, Affleck et al., 2005) even when accounting for genetic factors (Gunthert et al., 2007). Furthermore, depression appears to have no lasting impact on neuroticism scores (Shea et al., 1996). Finding significant differences between depression groups after controlling for neuroticism would therefore suggest that these effects were due to scarring and not vulnerability. We addressed the priming hypothesis in a similar manner by controlling for current depressive symptoms. Students experiencing heightened psychological duress may be primed to have stronger emotional reactions on high-stress days; significant differences in stress-reactivity across depression groups in the presence of this covariate would argue against priming as an explanation of these results.

A secondary aim concerned the role of positive affect in the stress and coping process. We anticipated that all students would show lower positive affect and higher negative affect on more stressful days. More importantly, given evidence of heightened stress-reactivity in people with depression (Bylsma et al., 2011; Wichers et al., 2007a), we expected that the inverse relation between negative and positive affect on higher stress days would be stronger for students with a history of depression. In other words, the moderation of the daily stress-negative affect relation by positive affect would be more pronounced among those who had previously experienced depression. Although this pattern of results could be explained by different psychological processes (i.e., affect polarization vs. positive affect buffering; Fredrickson, 2001; Zautra et al., 2000), the current study was not designed to distinguish between these theories and considers such a finding as support for either explanation. Finally, in a more exploratory fashion, we examined whether students with remitted depression would exhibit higher average levels of daily stress and negative affect, and lower average levels of positive affect across the study month than students with no history.

Method

Participants and Procedure

As part of a project examining daily experiences and alcohol use, 1818 college students were recruited over nine semesters (Spring 2008 – Spring 2012) at a large, state university through the undergraduate psychology participant pool and an email-based campus-wide announcements system. To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years old, have consumed alcohol at least twice in the past 30 days, and never undergone treatment for alcohol problems. Participants first completed an online baseline survey containing demographics and a variety of personality and attitude measures approximately 1 month following the start of the semester. During this period, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) was administered to students over the phone, with each participant randomly assigned to one interviewer. DIS interviews were conducted by a Master’s-level research assistant with 20 years of diagnostic experience as well as several clinical psychology graduate students trained to criterion by that assistant. All interview activities were supervised by a clinical psychologist. Prior research has validated the assessment of depression by phone using the DIS, as it shows acceptable agreement with face-to-face administration (Wells, Burnam, Leake, & Robins, 1988).

Approximately 2 weeks after completing the baseline assessments, participants began the daily diary study. Students accessed a secure website to complete a brief survey containing the daily mood and stress questions each day for 30 days between the hours of 2:30–7:00 PM. This time window was selected to coincide with the end of the school day for most undergraduate students, but before they began their evening activities, thereby reducing the risk of students reporting when under the influence of alcohol. If participants missed that day’s survey, they could contact the researchers to complete it late, up to 11:00 AM the next morning. Students were paid and, when applicable, provided with classroom credit for both the baseline survey/DIS and the daily diary study.

Ninety-eight students were omitted from the final analysis due to diagnostically ambiguous responses on the DIS: 26 had incomplete data that prevented a diagnosis; 33 reported depression due to alcohol/drug use or physical illness/injury; and 39 reported recent or remitted minor depression. In addition, 8 students were omitted due to missing baseline data. Finally, 163 individuals who had a daily survey compliance rate of less than 15 days were omitted from the analyses, leaving a final sample of 1549 students (Table 1) who completed 40,842 daily diary entries (M = 26.3; SD = 3.9). Men were more likely than women to be omitted from the sample, χ2(1) = 10.83, p = .001; no other variables predicted exclusion. The final sample ranged in age from 18 to 31 years (M = 19.2, SD = 1.4); was 54% female; and 80% White, 11% Asian-American, 4% African-American/Black, 4% Latino or Hispanic American, and 1% Native American, other, or missing.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Depression History

| No Depression History (n = 1064) | Remitted Depression (n = 278) | Recent Depression (n = 207) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % or M | SD | % or M | SD | % or M | SD | |

|

| ||||||

| Gender (% Female)* | 51%a | 59%b | 58%b | |||

| Age (years)* | 19.2 | 1.3 | 19.4 | 1.8 | 19.4 | 1.6 |

| Neuroticism*** | 3.4a | 0.7 | 3.7b | 0.7 | 4.0c | 0.8 |

| BDI*** | 3.0a | 3.6 | 5.0b | 4.8 | 7.8c | 6.2 |

Note. Asterisks indicate significant differences across groups (*p < .05; ***p < .001); differing superscripts indicate significant between-group differences. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory (short form). Neuroticism measured on a 1–7 scale; BDI measured on a 0–39 scale.

Baseline Measures

Depression history was measured using the DIS. A major depressive episode was diagnosed when participants endorsed at least one of two required symptoms (feeling sad, depressed, or empty most of the time; loss of interest in or pleasure from normal activities) over a 2-week period in their lifetime, along with at least three other symptoms during that same span (i.e., changes in sleeping, appetite, energy, or ability to concentrate). Endorsement of fewer than three other symptoms produced a diagnosis of minor depression. If students met criteria for a major depressive episode that was not attributable to alcohol/drug use or physical illness/injury, and had not experienced major or minor depression in the past year, they were categorized as having remitted depression. These students were compared to two other groups: those who reported no past or recent major or minor depression were categorized as never depressed, and those who reported a major depressive episode in the past year not due to alcohol/drug use or illness/injury were categorized as recently depressed.

Neuroticism was measured in the baseline survey with 48 items from the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Participants responded to each statement using a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and responses were averaged, α = .93.

Current depressive symptoms were also measured in the baseline survey with the short-form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Beck, 1972). These 13 items asked participants to report mood and behavioral disturbances experienced in the past week, using a 4-point scale approximating not at all depressed (0) to seriously depressed (3). These items were summed, with a possible range of 0–39, α = .87.

Daily Measures

Positive and negative affect were measured by asking students to rate how they felt that day from the time they awoke until taking the daily survey. Participants were presented with 30 affect words and rated each on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). For each subscale, face valid items were chosen by the researchers based on Larsen and Diener’s (1992) circumplex model of emotion. Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was calculated for each subscale across all person-days. Depressed affect was assessed with “sad,” “unhappy,” and “dejected,” α = .83; anxious affect with “anxious” and “nervous,” α = .72; hostile affect with “angry” and “hostile,” α = .76; and positive affect with “happy,” “enthusiastic,” “content,” and “cheerful,” α = .89.

Perceived stress was measured by asking participants to rate the day’s overall stressfulness from 1 (not at all stressful) to 7 (extremely stressful). Prior research has established the validity and reliability of single-item measures of perceived psychosocial stress (Littman, White, Satia, Bowen, & Kristal, 2006). Furthermore, this item was preceded by having students rate the occurrence of various stressors common to college students (e.g., taking an exam), thereby cueing a thoughtful recollection of the day’s stressfulness.

Analysis

Daily diary studies produce data with a hierarchical structure in which the repeated, daily measures (Level 1, or L1) are clustered within individuals (Level 2, or L2). To account for non-independence of data, hypotheses were tested using multilevel modeling with HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). This technique allows for simultaneous estimation of within- and between-person effects, as well as prediction of both intercepts and slopes. Additionally, multilevel modeling does not require equal numbers of observations from each participant, making it robust to data missingness. Data were modeled with an unstructured covariance matrix, and models were estimated with full maximum likelihood to allow for χ2-difference testing of model fit for both fixed and random effects using the −2 log likelihood statistic. Five different daily measures were individually modeled as continuous outcomes: stress appraisals, positive affect, depression, anxiety, and hostility. The main effects models predicting daily affect presented in Table 2 show the unstandardized coefficients for each L1 and L2 predictor when tested sans other predictors at the same level (with the exception that all interactions were tested with the corresponding component predictors in the model). Finally, all retained effects from these individual models were tested together in a final combined model to determine which predictors had significant unique effects (Hox, 2010), the results of which are also presented with unstandardized coefficients in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multilevel Models Predicting Daily Affect

| Daily Outcomes | Level 2 Predictors (fixed effects) | Individual Main Effects Models

|

Final Combined Models

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Daily Stress Slope1 | Daily Positive Affect Slope1 | Daily Stress1 x Positive Affect Slope1 | Intercept | Daily Stress Slope1 | Daily Positive Affect Slope1 | Daily Stress1 x Positive Affect Slope1 | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Positive Affect | Intercept | 2.680*** | −.178*** | 2.497*** | −.163*** | ||||

| None v remitted | .166*** | .025* | .069† | .027** | |||||

| Recent v remitted | −.075 | −.003 | .041 | −.009 | |||||

| Neuroticism2 | −.275*** | .001 | −.250*** | .009 | |||||

| BDI2 | −.036*** | .001 | −.014** | .001 | |||||

| Gender3 | .154*** | −.055*** | .246*** | −.057*** | |||||

| Age2 | −.039*** | .002 | ---- | ---- | |||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Depressed Affect | Intercept | 1.404*** | .130*** | −.269*** | −.210*** | 1.406*** | .090*** | −.191*** | −.068*** |

| None v remitted | −.128*** | −.027*** | .067** | .020* | −.039 | −.016* | .041* | .018* | |

| Recent v remitted | .136*** | −.004 | −.080** | −.003 | .030 | −.019† | −.062* | −.002 | |

| Neuroticism2 | .222*** | .025*** | −.084*** | −.009* | .129*** | .010* | −.060*** | −.005 | |

| BDI2 | .038*** | .005*** | −.009*** | −.001 | .024*** | .004*** | .001 | .001 | |

| Gender3 | .050* | −.001 | −.093*** | −.016* | −.014 | −.008 | −.071*** | −.013* | |

| Age2 | −.009 | .002 | .001 | −.002 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Anxious Affect | Intercept | 1.729*** | .239*** | −.193*** | −.041*** | 1.686*** | .201*** | −.011 | −.046*** |

| None v remitted | −.140*** | −.017† | .047* | .024* | −.040 | −.006 | .049* | .022* | |

| Recent v remitted | .155** | .026† | .001 | .031* | .051 | .019 | −.011 | .031* | |

| Neuroticism2 | .270*** | .035*** | −.009 | −.003 | .186*** | .029*** | −.009 | .001 | |

| BDI2 | .038*** | .003*** | .002 | .001 | .017*** | −.001 | .005* | .001 | |

| Gender3 | .160*** | .054*** | −.065*** | −.024** | .085*** | .045*** | −.063*** | −.024** | |

| Age2 | −.010 | .001 | −.007 | .004 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Hostile Affect | Intercept | 1.299*** | .093*** | −.152*** | −.104*** | 1.317*** | .076*** | −.076*** | −.043*** |

| None v remitted | −.054* | −.024*** | .027 | .015† | .001 | −.014† | .014 | .011 | |

| Recent v remitted | −.029 | −.016 | −.052* | .006 | −.029 | −.016 | −.052* | .006 | |

| Neuroticism2 | .106*** | .013** | −.027* | −.007 | .106*** | .013** | −.027* | −.007 | |

| BDI2 | .014*** | .003** | .001 | .001 | .014*** | .003** | .001 | .001 | |

| Gender3 | −.064*** | −.007 | −.055*** | −.016* | −.064*** | −.007 | −.055*** | −.016* | |

| Age2 | −.015** | .004* | −.002 | −.003 | −.015** | .004* | −.002 | −.003 | |

Note.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001;

p < .10.

Person-mean centered;

Grand-mean centered;

Coded: 0 = male, 1 = female. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory (short form). Values are unstandardized coefficients. All within-person effects (intercept and slopes) included a random effect. Dashed lines indicate a between-person effect omitted from the final combined model due to a non-significant improvement in model fit (−2*log likelihood).

L1 models

For each outcome, an intercept-only model was first tested and the intraclass correlation was computed; daily stress appraisals were predicted using just the intercept-only model. For daily affect, we individually tested each within-person predictor: all fixed and random effects significantly improved model fit across outcomes and were retained in the final models. Models for daily positive affect included daily stress as a within-person predictor. Separate models for daily depression, anxiety, and hostility predicted these outcomes from daily stress, daily positive affect, and a daily stress × daily positive affect interaction. All L1 predictors were person-mean centered, and thus L1 coefficients reflect deviations from a person’s average level of that variable of interest (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). A significant and negative slope for daily stress on positive affect would indicate stress-reactivity, as would a significant and positive slope for daily stress on depressed, anxious, or hostile affect. Furthermore, a significant daily stress × daily positive affect interaction for any of the negative affect outcomes would provide evidence for both affect polarization and positive affect buffering. However, the main goals of this study (i.e., how stress-reactivity and positive affect relate to history of depression) required testing individual differences at L2.

L2 models

After establishing the L1 models, we individually tested each between-person variable as a predictor of the intercept and all slopes, retaining predictors that significantly improved model fit (only age was trimmed from models predicting daily stress appraisals, positive affect, depressed affect, and anxious affect). The comparison of individuals with remitted depression, recent depression, and no history of depression was accomplished with dummy codes, using the remitted depression group as the reference. These dummy codes were un-centered, as was gender (0 = male, 1 = female); all other L2 predictors (i.e., age, neuroticism, and current depressive symptoms) were grand-mean centered.

To examine stress-reactivity as a function of depression history, we tested cross-level interactions between daily stress (L1) and the depression dummy codes (L2). Significant effects would indicate differences in stress-reactivity between the no depression group or the recent depression group versus the remitted depression group. Additionally, to test whether effects would be best interpreted as evidence of scarring, vulnerability, or priming, we controlled for neuroticism and current depressive symptoms at L2. As previously described, a significant daily stress × depression interaction in the presence of neuroticism would suggest these effects are due to scarring and not vulnerability. Similarly, finding that same interaction when controlling for current depressive symptoms would suggest the effect could not be attributed to priming. As a secondary aim, we also tested daily stress × daily positive affect × depression interactions to examine how the role of positive affect in the daily stress and coping process differs based on depression history. Simple slopes for significant cross-level interactions were calculated using procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006; see http://www.quantpsy.org/interact/index.html).

Results

Descriptive Results

In the final sample, 1064 students (69%) had no history of major or minor depression, 278 (18%) had remitted depression, and 207 (13%) had recent depression (Table 1). These figures are comparable to other reports of lifetime prevalence among young adults (Hankin et al., 1998), although they appear somewhat elevated for past-year prevalence among college students, which was reported as 8% in a national sample (SAMHSA, 2012). Women were more likely than men to have remitted or recent depression, and although there were significant age differences across the three groups as indicated by an analysis of variance, Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed no significant between-group differences.

Examination of the psychological covariates highlighted distinctions between the three groups of students: students with recent depression scored highest in terms of neuroticism and current depressive symptoms, followed by students with remitted depression, and finally those with no history of depression. Importantly, average depressive symptoms for the remitted depression group (M = 5.0, SD = 4.8) were relatively low, while average depressive symptoms for the recent depression group (M = 7.8, SD = 6.2) could be described as mild-to-moderate (Beck & Beck, 1972). As expected, neuroticism and current depressive symptoms were strongly correlated, r = .58, p < .001, although not to a degree that indicated collinearity.

Intraclass correlations were calculated based on intercept-only models to determine whether the affective outcomes showed substantial within-person daily variation. The value of this correlation indicates the proportion of variance explained in the repeated measure at the between-person level: positive affect = .449; depressed affect = .386; anxious affect = .344; hostile affect = .373. In effect, more than half and up to two-thirds of the variance in each outcome was attributable to within-person differences, which is indicative of significant day-today affective variation.

Appraisals of Daily Stress

First, we analyzed whether students with a history of depression reported higher average daily stress appraisals. In the final combined model, students who had never experienced depression reported lower average daily stress than students with remitted depression, b = −.16, p = .005. Students with remitted versus recent depression did not differ. These results controlled for neuroticism and current depressive symptoms, both of which predicted higher average daily stress, ps ≤ .001. Finally, female students reported higher average daily stress than male students, b = .38, p < .001.

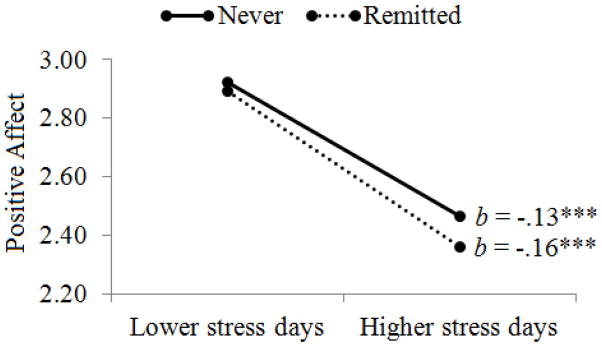

Positive Affect Stress-reactivity

Results for the multilevel models predicting daily affect are presented in Table 2. Again, within-person (L1) predictors were person-mean centered, indicating that higher stress days were defined relative to each individual’s average level of stress. In the final combined model, higher stress days were characterized by lower positive affect. Depression status did not predict average levels of positive affect, but as depicted in Figure 1, students with remitted depression showed greater decreases in positive affect on higher stress days (simple slope: b = −0.16, p < .001) than students with no history of depression (simple slope: b = −0.13, p < .001). There were no differences in stress-reactivity between students with remitted versus recent depression. In addition, higher average levels of positive affect were experienced by female students as well as those with lower scores for neuroticism and current depressive symptoms. Only gender, however, moderated stress-reactivity such that women showed significantly greater reductions in positive affect on higher stress days.

Figure 1.

Daily positive affect as a function of daily stress and depression history. Lower and higher stress days illustrated as +/− 1 standard deviation. ***p < .001.

Negative Affect Stress-reactivity

In the final combined models for daily negative affect, higher stress days were characterized by higher levels of depressed, anxious, and hostile affect. Average levels of daily negative affect did not differ between depression groups, but students with remitted depression showed relatively greater increases in depressed affect on higher stress days than students with no history of depression. This interaction, however, was qualified by a three-way daily stress × daily positive affect × depression interaction, described below. Again, students with remitted versus recent depression did not differ in stress-reactivity. Among the other predictors, greater stress-reactivity was shown by younger students for hostile affect; female students for anxious affect; students with higher current depressive symptoms for depressed and hostile affect; and students with higher neuroticism for all negative affect.

Interactions between Daily Stress and Daily Positive Affect

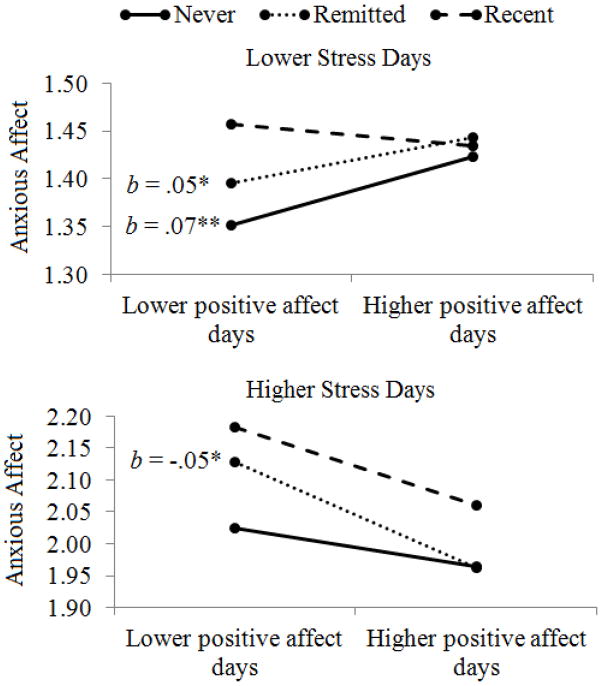

A significant daily stress × daily positive affect interaction would provide evidence of stronger affect polarization on higher stress days and/or buffering of the daily stress-negative affect relation by positive affect. This interaction was significant and in the expected direction across models, indicating that on higher stress days, higher positive affect was associated with lower depressed, anxious, and hostile affect. For depressed and anxious affect, this pattern was further qualified by a three-way, cross-level interaction (i.e., L1 × L1 × L2) with depression history. As illustrated in Figure 2 for anxious affect, students with both remitted depression (simple slope: b = 0.05, p < .05) and no history of depression (simple slope: b = 0.07, p < .01) showed positive relations between daily positive affect and anxiety on lower stress days, whereas there was a null relation among those with recent depression. On higher stress days, however, all three groups showed a negative relation between positive affect and anxiety, although this relation was only significant for students with remitted depression (simple slope: b = −0.05, p < .05). An alternative interpretation of this interaction consistent with the broaden-and-build theory is that the positive relation between daily stress and negative affect was weaker on days characterized by higher positive affect, especially for students with remitted depression. Besides depression history, only gender moderated the daily stress × daily positive affect interaction such that there was a stronger relation between positive affect and all three negative affect outcomes on higher stress days among women versus men.

Figure 2.

Daily anxious affect as a function of daily stress, daily positive affect, and depression history. Lower and higher stress days and positive affect days illustrated as +/− 1 standard deviation. Only significant simple slopes are provided; *p < .05, **p < .01.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that college students with remitted depression, despite having no current diagnosis of depression and reporting a relatively low BDI score, showed elevated stress-reactivity in terms of greater decreases in positive affect and increases in depressed affect as compared to students with no history of depression. Students with remitted depression, however, generally showed no differences from students with recent depression. These findings held when controlling for neuroticism and current depressive symptoms, suggesting that the experience of depression may create a “scar” in terms of heightened stress-reactivity, not that stress-reactivity was a preexisting vulnerability for depression or a function of priming. Furthermore, although these effects were relatively small, they represent affective fluctuations at the daily level that could have a clinically relevant cumulative effect. Having more extreme emotional reactions to stress, which may conceivably occur repeatedly during the day, suggests that students who formerly experienced depression may be particularly vulnerable to recurrence if they are not identified as at-risk (Cohen et al., 2005; Parrish et al., 2011; Segal et al., 2006). It is noteworthy that depression status did not predict average levels of daily affect, despite predicting average levels of daily stress. It was only when examining within-person slopes for daily affect that the hidden vulnerability conferred by a history of depression was identified. These findings speak further to the importance of micro-longitudinal methods in studying depression and mood, as global measures may not have distinguished between depression groups.

We also found evidence supporting both polarization of positive and negative affect on higher stress days (Zautra et al., 2000) and buffering of the daily stress-negative affect relation by daily positive affect (Fredrickson, 2001). Consistent with previous research, positive and negative affect were nearly orthogonal on lower stress days; in fact, students with remitted depression or no history of depression showed a positive relation between positive and negative affect on these days. On days when students with remitted depression experienced higher stress than usual, however, a negative relation between positive and both depressed and anxious affect emerged. Although the examination of stress and coping at the daily level is more consistent with the dynamic model of affect, which considers affect polarization an adaptive response to threat, these analyses cannot rule out the broaden-and-build theory, which argues that positive affect serves as a resource to facilitate coping with stress. Regardless of the exact mechanism, these findings suggest that the lingering effects of depression may lie in wait until moments of heightened duress. Interestingly, these data also suggest that the benefits of positive emotions are most pronounced among individuals with remitted depression, perhaps because they generally experience below-average levels of positive affect and, therefore, benefit the most when positive affect is relatively high (Peeters et al., 2003; cf. Ong et al., 2006).

Finally, it should be acknowledged that results differed across types of negative affect. Depression history moderated stress-reactivity only for depressed affect, and relations between daily stress and positive affect only for depressed and anxious affect. This discrimination validates examining different types of negative affect and indicates that each may serve unique roles in the stress and coping process. These results suggest that depression history influences internalizing reactions to stress (i.e., depression and anxiety) more so than externalizing reactions (i.e., hostility). Future studies may consider also differentiating types of positive affect to determine whether they have specific interactive effects with daily stress (Tugade, Fredrickson, & Barrett, 2004), and whether those processes vary by depression history.

Alternative Perspectives on Emotional Variability and Depression

A recent yet extensive literature provides evidence that cognitive flexibility, consisting of the ability to adapt one’s emotional state to meet situational demands, is a cornerstone of mental health (for a review, see Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Such a perspective appears to stand in contrast to the current results (along with Gruber et al., 2013) which suggest that emotional reactivity is a risk factor for depression (Cohen et al., 2005; Parrish et al., 2011; Segal et al., 2006). However, one could argue that heightened stress-reactivity reflects a rigid cognitive response to stress (i.e., lack of cognitive flexibility) in that students with a history of depression appeared to reliably respond to stress with greater decreases in positive affect and greater increases in depressed affect than other students. This idea is further supported by the finding that neuroticism, a fairly stable personality trait associated with both ineffective coping and heightened risk for depression (Gunthert et al., 1999; Klein et al., 2012; Shea et al., 1996) was related to greater stress-reactivity for negative affect.

Additionally, there is evidence that depression is related to emotional context insensitivity (i.e., blunted responses to both positive and negative stimuli; Bylsma, Morris, & Rottenberg, 2008), which also appears to contradict current and prior findings related to stress-reactivity. However, evidence diverges between laboratory and field studies (see Bylsma et al., 2011), with the current results fitting the pattern that studies of real-life stress among individuals with a history of depression tend to demonstrate heightened reactivity and emotional lability (Larson et al., 1990; Silk et al., 2011; Wichers et al., 2007a; cf. Peeters et al., 2003). Additionally, students with recent depression showed no differences in negative affect based on daily stress and positive affect, which may be evidence of blunting among those who had experienced a depressive episode in the past year. Further research is needed to determine whether reactivity and blunting may represent different phases in the etiology of a depressive episode, or if certain categories of stimuli (e.g., social versus non-social) are reliably subject to more labile reactions versus blunting.

Implications

These results have various implications for the application and assessment of interventions for a variety of mental and physical health conditions. People with a history of depression may require tailored interventions to overcome their emotional or cognitive vulnerabilities. For example, patients undergoing cognitive therapy for depression and/or anxiety disorders showed worse outcomes when they were more stress-reactive at entry (Cohen et al., 2005). Even patients with depression brought to remission through the use of cognitive therapy or psychopharmacological medications were at greater risk of relapse within 18 months if they showed greater stress-reactivity (Segal et al., 2006). Fortunately, research has demonstrated that cognitive therapy can be effective in reducing stress-reactivity, along with depressive symptoms, among patients with depression (Parrish et al., 2009). The effects of depression history on intervention efficacy, however, may not be limited to treatments for depression. For example, people in treatment for rheumatoid arthritis showed worse psychological (e.g., coping efficacy) and physical (e.g., joint tenderness) outcomes from cognitive behavioral therapy versus mindfulness meditation when they had a history of recurrent depression (Zautra et al., 2008).

These results also highlight the importance of positive affect in mental health outcomes. Students with remitted or recent depression showed the largest decrements in positive affect on higher stress-days, and those with remitted depression also appeared to experience the greatest benefits of positive affect on these days. Although the observed differences were small, such daily variation in positive affect may have cumulative, detrimental effects on mental and physical health. These relatively larger decreases in positive affect on higher-stress days could foster psychological dysfunction among people who have experienced depression, even when in remission (Pruchno & Meeks, 2004), as these decrements could inhibit coping and prevent opportunities for growth that might otherwise occur (Fredrickson, 2001). In fact, positive affect variability in response to common daily stressors may represent a risk factor for worse mental health outcomes (Gruber et al., 2013). Efforts to increase and stabilize positive affect among individuals who have experienced depression may, therefore, bolster personal resources or foster psychological resilience (Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008; Ong et al., 2006), subsequently improving individuals’ ability to cope with stress and decreasing negative affect.

In addition to intervention work, these findings have implications for research on depression and stress. Studies examining the effects of depression on any mental or physical health outcome should consider including people with remitted depression, as this study and others suggest that these individuals exhibit many of the same vulnerabilities as those with a current or recent diagnosis (e.g., Conner et al., 2006; O’Grady et al., 2010; Tennen et al., 2006; Zautra et al., 2007). Furthermore, many studies across disciplines control for current diagnoses of depression or omit these participants completely. Failing to account for remitted depression may complicate these studies and obscure potentially important results.

Limitations

Alone, these findings cannot speak directly to the various theories (i.e., scarring, priming, and vulnerability) proposed to explain depression recurrence. Although we found differences in stress-reactivity by depression group when controlling for neuroticism and current depressive symptoms, suggesting that depression leaves psychosocial scars that lead to greater stress-reactivity, the cross-sectional nature of the study prohibits drawing a definitive causal link. It is worth noting, however, that our results are in line with prior ecological momentary assessment research with adolescent clinical samples, showing greater levels of negative affect and affect polarization in the face of daily stress (e.g., Larson et al., 1990; Silk et al., 2011). Future research will need to examine daily stress-reactivity in a prospective framework to determine whether this psychological process predates first onset of depression and how it may change following a depressive episode.

A second issue is that all measures were self-reported, including the use of retrospective measures to diagnose depression. In some cases, students were asked to remember behaviors and emotions that may have occurred over a decade previously, and when they were children. Although by far the most common approach in the literature, reliance on personal recall is less than ideal. However, a population-based study showed moderate reliability of depressed mood measured with the DIS over a 13-year period (Thompson, Bogner, Coyne, Gallo, & Eaton, 2004), providing some reassurance to its validity in the current study. Finally, we used a single-item measure of perceived stress, which is not ideal from a psychometric standpoint. However, prior research has established the validity and reliability of single-item stress measures (Littman et al., 2006), and participants in the current study needed only to evaluate stress for a single day as opposed to the past year (as in Littman et al.). Furthermore, students completed the perceived stress measure after responding to several items regarding events of their day, bolstering our confidence in this measure. Unfortunately, use of this item prohibited us from examining whether depression history predicted differences in exposure to stressors, although to some degree individuals’ appraisals of stress may be more important in understanding stress-reactivity.

Conclusion

The current study indicates that individuals with a history of depression, even if in remission, may be at heightened risk for a recurrent depressive episode due to increased stress-reactivity. From a theoretical standpoint, this suggests that history of depression serves as a marker, if not a cause, of psychological vulnerabilities that influence individuals’ day-to-day appraisals of and reactions to stress. Future research should continue to examine the relations between stress, negative affect, and positive affect as they unfold in daily life. Furthermore, clinicians and researchers alike are advised to measure depression history and not just current depressive symptoms or psychiatric diagnoses when screening for mental health issues.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 5P60-AA003510, and preparation of this manuscript was supported by grant 5T32-AA07290, both from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank Jennifer Scanlon Kim for help with data organization and analysis.

Contributor Information

Ross E. O’Hara, Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut Health Center

Stephen Armeli, Department of Psychology, Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Marcella H. Boynton, Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut Health Center

Howard Tennen, Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, University of Connecticut Health Center.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgraduate Medicine. 1972;52:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:959–985. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Taylor-Clift A, Rottenberg J. Emotional reactivity to daily events in major and minor depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:155–167. doi: 10.1037/a0021662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LH, Gunthert KC, Butler AC, O’Neill SC, Tolpin LH. Daily affective reactivity as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1687–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner T, Tennen H, Zautra A, Affleck G, Armeli S, Fifield J. Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain in daily life: Within-person analyses reveal hidden vulnerability for the formerly depressed. Pain. 2006;126:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R. Professional manual. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEIO PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Kogan A, Quoidbach J, Mauss IB. Happiness is best kept stable: Positive emotion variability is associated with poorer psychological health. Emotion. 2013;13:1–6. doi: 10.1037/a0030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert KC, Cohen LH, Armeli S. The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1087–1100. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert KC, Conner TS, Armeli S, Tennen H, Covault J, Kranzler HR. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and anxiety reactivity in daily life: A daily process approach to gene-environment interaction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:762–768. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157ad42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Taylor & Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Husky MM, Mazure CM, Maciejewski PK, Swendsen JD. Past depression and gender interact to influence emotional reactivity to daily life stress. Cognitive Therapy Research. 2009;33:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s10608-008-9212-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:631–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Kotov R, Bufferd SJ. Personality and depression: Explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E. Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion. In: Clark MS, editor. Emotion: Review of personality and social psychology. Vol. 13. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Raffaelli M, Richards MH, Ham M, Jewell L. Ecology of depression in late childhood and early adolescence: A profile of daily states and activities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:92–102. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.99.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman AJ, White E, Satia JA, Bowen DJ, Kristal AR. Reliability and validity of 2 single-item measures of psychosocial stress. Epidemiology. 2006;17:398–403. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000219721.89552.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Kaufman JS, Frost KH, Fitzmaurice GM, Weiss RD. Positive affect and stress-reactivity in alcohol-dependent outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:152–157. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, deVries MW, Delespaul P, van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: An experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;107:124–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady MA, Tennen H, Armeli S. Depression history, depression vulnerability and the experience of everyday negative events. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:949–974. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.9.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish BP, Cohen LH, Gunthert KC, Butler AC, Laurenceau JP, Beck JS. Effects of cognitive therapy for depression on daily stress-related variables. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish BP, Cohen LH, Laurenceau JP. Prospective relationship between negative affective reactivity and to daily stress and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2011;30:270–296. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.3.270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters F, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Delespaul P, deVries M. Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:203–211. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno RA, Meeks S. Health-related stress, affect, and depressive symptoms experienced by caregiving mothers of adults with a developmental disability. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:394–401. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT. HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. Computer software manual. [Google Scholar]

- Robotham D, Julian C. Stress and the higher education student: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Further and Higher Education. 2006;30:107–117. doi: 10.1080/03098770600617513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Kennedy S, Gemar M, Hood K, Pedersen R, Buis T. Cognitive reactivity to sad mood provocation and the prediction of depressive relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:749–755. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Solomon DA, Warshaw MG, Keller MB. Does major depression result in lasting personality change? The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:1404–1410. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Jakubcak JL, Thompson WK, Ryan ND, Dahl RE. Daily emotional dynamics in depressed youth: A cell phone ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2011;110:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand EB, Zautra AJ, Thoresen M, Ødegård S, Uhlig T, Finset A. Positive affect as a factor of resilience in the pain-negative affect relationship in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The NSDUH report: Major depressive episode among full-time college students and other young adults, aged 18 to 22. Rockville, MD: May 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Martin R. The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: Reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1485–1510. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Watson D, Clark LA. On the dimensional and hierarchical structure of affect. Psychological Science. 1999;10:297–303. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G. Blaming others for threatening events. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:209–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G, Zautra A. Depression history and coping with chronic pain: A daily process analysis. Health Psychology. 2006;25:370–379. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Bogner HR, Coyne JC, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW. Personal characteristics associated with consistency of recall of depressed or anhedonic mood in the 13-year follow-up of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Burnam MA, Leake B, Robins LN. Agreement between face-to-face and telephone-administered versions of the depression section of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Journal Psychiatric Research. 1988;22:207–220. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M, Geschwind N, van Os J, Peeters F. Scars in depression: Is a conceptual shift necessary to solve the puzzle? Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:359–365. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, Peeters F, Kenis G, van Os J. Genetic risk of depression and stress-induced negative affect in daily life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007a;191:218–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, Peeters F, Kenis G, van Os J. Evidence from moment-to-moment variation in positive emotions buffer genetic risk for depression: A momentary assessment twin study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007b;115:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Uhmann S. The timing of depression: An epidemiological perspective. Medicographia. 2010;32:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, Davis MC. Dynamic approaches to emotions and stress in everyday life: Bolger and Zuckerman reloaded with positive as well as negative affects. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1511–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassio P, Tennen H, Irwin MR. Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptations to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:408–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Johnson LM, Davis MC. Positive affect as a source of resilience for women in chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:212–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Parrish BP, VanPuymbroeck CM, Tennen H, Davis MC, Reich JW, Irwin M. Depression history, stress, and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Reich JW, Davis MC, Potter PT, Nicolson NA. The role of stressful events in the relationship between positive and negative affects: Evidence from field and experimental studies. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:927–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Smith B, Affleck G, Tennen H. Examinations of chronic pain and affect relationships: Applications of a dynamic model of affect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:786–795. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]