Abstract

Mexican American (MA) elders are more functionally impaired at younger ages than other elders yet use home care services (HCS) less. To determine possible reasons, nine questionnaires were completed in Spanish or English by MA elders and caregivers living in southern Arizona (n=280). Contextual, personal, and attitudinal factors were significantly associated with use of HCS; and cultural/ethnic factors were significantly associated with confidence in HCS. Interventions should be designed and tested to increase use of HCS by Mexican American elders, by increasing service awareness and confidence in HCS, while preserving expectations of familism and reducing caregiving burden.

Keywords: utilization, home care services, Mexican American elders, family caregiving

Mexican American (MA) elders, the fastest growing group of elders in the United States (U. S.) (U.S. Census, 2002), are more functionally impaired at younger ages than either Anglo elders (Torres, 2001). MA elders, however, use home care services (HCS), an intervention that may limit decline or complications, less than other groups (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2003). Family care has been recognized as preventing costly institutionalizations (Covinsky, 2001). The “parent support ratio” (people aged 80 and over per 100 persons aged 50–64) will increase from 11 in 1990 to 36 in 2050 (U. S. Census). The primary aim of the study was to test a model that showed factors that affect use of home care services by Mexican American elders.

National policy has been designed to keep people in the home and out of institutions (Covinsky et al., 2001). Studies show elders who use HCS have better outcomes than those who do not (Madigan, Tullai-McGuinness, & Neff, 2002). Use of HCS prevents the onset of acute illness, controls acute illness episodes, and helps manage chronic conditions (Anderson & Horvath, 2002). Recent studies revealed that use of HCS among MA elders is a complex phenomenon that includes caregivers’ perspectives (Crist, García-Smith, & Phillips, 2006). To date, no theory has captured this complexity. A tested model can guide development of theory-driven nursing interventions to increase MA elders’ use of HCS to improve outcomes. In this article, we report factors that are significantly related to MA elders’ use of HCS. Home care services are skilled services provided by registered nurses; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; social workers, and other professionals; as well as supportive services provided by home care aides and housekeepers.

Conceptual Framework

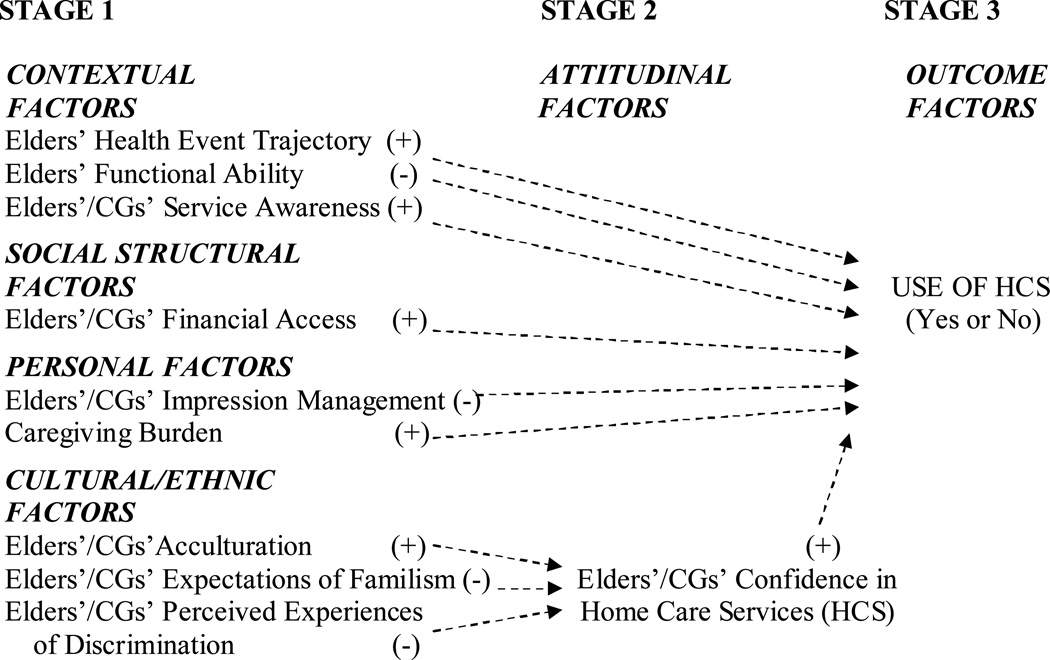

Use of HCS has previously been studied using elder characteristics and data found in national databases. Studies have shown certain factors that partially predict MA elders’ use of HCS (Magilvy & Congdon, 2000); however, the explained variance of these predictors has been relatively small with a median r2=19% for 139 utilization studies using the Andersen and Aday organizing model (Phillips, Morrison, Andersen, & Aday, 1998). Other factors, such as contextual, personal, and cultural/ethnic factors also potentially affect use of HCS (Crist, 2002). Knowledge also is limited about both MA elder and family caregiver predictors, which theoretically have promise for affecting use of HCS by MA families. A model was synthesized which incorporated factors from the literature, and recently discovered factors. The model was proposed to more comprehensively explain MA elders’ use of HCS than previous research (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mexican American Elders’ and Family Caregivers’ Use of Home Care Services Theory.

Hypothesized direction of factors’ effect on use depicted with (+) or (−) and dotted lines.

Contextual, Social Structural, Personal, and Cultural/Ethnic Factors

Contextual Factors

Contextual factors are defined as health and healthcare related factors that shape the situation within which elders receive family care and can affect use of HCS directly. Contextual factors include three concepts: health event trajectory, functional ability, and service awareness. The first contextual factor, health event trajectory, is defined as either an acute or chronic pattern of decline in the elder’s condition. Both may increase the possibility of the elder’s using HCS; but elders or caregivers are more willing to accept services when the elder has acute and obvious decline. An acute pattern of decline is sudden, and usually associated with hospitalization, for example, stroke with hemiparesis, acute hypoglycemia, broken hip, heart attack with surgery, new ostomy, or knee surgery. An acute trajectory is more likely to affect use of HCS than a gradual and less dramatic change. We expected that use of HCS would be positively affected by MA elders’ health event trajectory.

The second contextual factor, elders’ functional ability, is defined as the elder’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) (e.g., bathing) or instrumental ADLs (IADLs) (e.g., shopping) independently (Murtaugh & Litke, 2002). This concept closely corresponds to the construct “need for services” in the literature, usually operationalized as objective and perceived health problems and functional limitations. Functional ability has often shown to be the strongest predictor of use of HCS by elders of Anglo (McCusker et al., 2001) and Mexican descent (Wallace et al., 1998) with a variety of diagnoses. We expected that use of HCS would be negatively affected by MA elders’ functional ability.

The third contextual factor, service awareness, is defined as elders’ and caregivers’ level of understanding about existing HCS (Crist, Michaels, Gelfand, & Phillips, 2007). We used a comprehensive definition of the concept with three dimensions: knowledge that HCS exist, recognition that HCS are needed, and potential to access HCS. We expected that use of HCS would be positively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ service awareness.

Social Structural Factors

Social structural factors are economic and other societal realities that affect access to care. Of particular interest in this study was availability of financial resources or financial access, which affects use of HCS directly. Financial access is defined as elder’s and caregivers’ ability to fund HCS. Funding may come from (1) third-party payer coverage, including Medicare, Medicaid, long term care and other health insurance, and/or eligibility to receive publicly funded aging services, and (2) private pay resources (Martin, Schoeni, Freedman, & Andreski, 2007). Having health insurance or personal resources positively affects use of HCS (Crist, 2002). We expected that use of HCS would be positively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ financial access.

Personal Factors

Personal factors are elders’ and family caregivers’ behaviors and perceptions about themselves and their families. Two concepts comprised the personal factors: impression management and caregiving burden. The first personal factor, impression management, is a social interactionist concept, defined as individuals’ or groups’ conscious or unconscious efforts to maintain their public image, or “front stage” appearance (Goffman, 1959). MA elders and their family caregivers engage in impression management behaviors to maintain the public’s positive view of their family. They perceive the prospect of using HCS to be embarrassing, believing that others who observe their use of HCS would assume that the family was not willing or able to carry out its responsibilities. We expected that use of HCS is negatively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ impression management.

The second personal factor, caregiving burden, is defined as family caregivers’ perceptions of the degree of difficulty they experience due to elders’ impairments. MA family caregivers place high value on providing care in the home and make every attempt to continue providing family care to their elders, within their cultural values. Burden in this study has two dimensions: caregivers’ assessment of elders’ impairment and caregivers’ perceptions of burden (Poulshock & Deimling, 1984). Perceptions of burden can be referenced by how tiring, difficult or upsetting caregiving tasks are on caregivers and may positively affect use of HCS. We expected that use of HCS would be positively affected by MA family caregivers’ caregiving burden.

Cultural/Ethnic Factors

Cultural/ethnic factors stem from conditions, cultural norms, or experiences of being part of an ethnic minority. They are acculturation, expectations of familism, and perceived experiences of discrimination (Crist, 2002). We theorized that their relationship to use of HCS would be mediated by the level of confidence in HCS. The first cultural/ethnic factor, acculturation, was defined as changes in attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and values of minority individuals coming into continuous, direct contact with a dominant cultural group (Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). The measure includes preferred language and time spent in the U. S. More acculturated minorities are more willing to use health and social services, according to Calderón-Rosado, Morrill, Chang, and Tennstedt (2002). We expected that confidence in HCS would be positively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ acculturation.

Familism is the belief that needs of the family supersede needs of the individual (Sábogal, Marín, & Otero-Sábogal, 1987). The second cultural/ethnic factor, expectations of familism, is defined as elders’ and family caregivers’ beliefs that all of the elders’ needs should be met by elders’ children, most often grown daughters, in return for previous sacrifices made by their parents. We expected that confidence in HCS would be negatively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ expectations of familism.

Discrimination is a social or institutional behavior that maligns a targeted group (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). The third cultural/ethnic factor, perceived experiences of discrimination, is MA people’s assumptions that they will not be treated with dignity and respect (respeto), or warm, friendly, person-oriented behavior (personalismo) by HCS providers, the majority of whom they expect will not speak or understand Spanish during the delivery of services (Alemán, 2000). We expected that confidence in HCS would be negatively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ perceived experiences of discrimination.

Attitudinal Factors

Attitudinal factors are perspectives of how people view the world. In this study, they shape elders’ and family caregivers’ perspectives toward the use of HCS. Of special interest was level of confidence in HCS. Confidence in HCS is defined as having two dimensions: (a) elders’ and family caregivers’ level of trust and confidence that care provided by outside providers coming into the home will be effective, and (b) fear and worry about whether care provided by outsiders coming into the home will be safe (Stommel, Collins, Given, & Given, 1999). “Mistrust of service delivery institutions” (Calderón-Rosado et al., 2002, p. 4) results in reluctance to use available community services (Alemán, 2000). We expected that use of HCS would be positively affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ confidence in HCS.

Stage 3 - Outcome

In this study, use of HCS is sustained, intermittent care delivered by visiting skilled or supportive care providers in elders’ homes. The two hypotheses tested were: (1) use of HCS will be affected by contextual, social structural, personal, and attitudinal factors; and (2) confidence in HCS will be affected by MA elders’ and their family caregivers’ cultural/ethnic factors.

Design

We designed this study as a cross-sectional survey to test the theoretical model, MA Elders’ and Caregivers’ Use of HCS Model. The University of Arizona human subjects committee approved the study.

Data Collection Procedures

Bicultural/bilingual research assistants recruited and assisted Mexican American elders (n=140) and caregivers (n=140) to complete nine questionnaires, in the participants’ homes or other places of choice in the community or the College of Nursing. Questionnaires were available in Spanish or English. About two-thirds (94; 67.9%) of the elders and about one-half (75; 53.6%) of the caregivers chose to complete the Spanish rather than English versions of the questionnaires. The research assistants presented and explained the consent form. Each elder received a copy. Participants completed the questionnaires during the same session, separately from each other so that responses of one would not affect responses of the other. Participants received $15.00 gift for completing the questionnaires. If elder participants of the dyads had recently been in the hospital, we collected data after at least 2 weeks of post-hospital discharge so at least two visits could naturally have occurred. One research assistant re-tested one newly developed questionnaire (Service Awareness Scale; Crist, Michaels et al., 2007) with randomly chosen 10% of the sample 7 days after the initial assessment.

Sample and Setting

We recruited the sample of 140 dyads (Mexican American elders paired with the family caregivers they identified as primary) at community events in a three-county area in Southern Arizona, such as health fairs, and by referrals by providers and previous participants. Inclusion criteria for elders were 55 years of age or older, male or female, of Mexican descent, able to read or speak Spanish or English, achieve a score of 6 or more on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ; Pfeiffer, 1975), have a chronic condition operationalized by receiving daily assistance with at least one ADL or two IADLs, and have a female family caregiver who either co-resides or lives within a 30-minute drive of the elder’s home. Inclusion criteria for caregivers were female, 21 years of age or older primary caregivers of eligible elders, of Mexican descent, able to read or speak Spanish or English, co-residing with the elder or living within a 30-minute drive of the elder’s home.

“Mexican American” refers to people of Mexican origin living in the U. S., excluding other Hispanic groups, who have different national backgrounds, immigration histories, customs, and patterns of using services than Mexican American people (Alemán, 2000). We set the criterion for “elder” as being ≥ 55 years of age, based on their earlier incidence of disability (Torres, 2001). A “chronic condition” is the state of sustained impaired functional ability, involving constant, recurrent, or progressive symptoms, and requiring ongoing skilled or supportive care (adapted from Anderson & Horvath, 2002). “Family caregiver” is a female family member or friend who provides assistance to the elder with at least one ADL or two IADLs daily.

Of elders, 74% were women and 26% were men. The mean age of elders was 73 (SD = 9.4; range of 55–94) years; of caregivers, 50 (SD = 13.8; range of 23–86) years. In relation to elders, 60% of caregivers were daughters; 21% were wives; 6% were daughters-in-law; and 13% were other (sister, granddaughter, friend). Of elders, 44% were widowed and 39% married, while the rest were divorced (13%) or single (4%). Most caregivers were married (59%) and 16% were divorced, while the rest were single (17%), widowed (4%), or separated (4%). About two-thirds of elders (69%) had achieved less than high school and one–fourth (24%) had completed high school, while the rest had been to college (7%). About 42% of caregivers had been to college while about one-third (34%) had completed high school and about one-fourth (24%) had achieved less than high school. Elders’ sole mean annual income ranged from $7,000 – $9,999. Caregivers’ sole mean annual income ranged from $4,000 – $4,999. Income information was reported in response to the Older Americans Resources and Services questionnaire (Fillenbaum, 1988). No distinction was made regarding reported vs. non-reported/cash-based income.

Measures

Table 1 contains descriptions of the measures we used. We represented the outcome use of HCS as a dichotomous variable that we created from elders’ and caregivers’ responses on the 9 “Utilization of Services” items (yes-no; if yes, how many visits) of the OMFAQ (Fillenbaum, 1988). If participants reported using any HCS with a total of two or more visits, the dichotomous DV was scored as “yes.” The representation of use of HCS was dichotomized to fit the research questions of this pilot study. Use of HCS in the past has been measured by “at least one home care visit” in many studies (Madigan et al., 2002). However, often elders or family caregivers agree to an initial visit, out of politeness or feeling pressured while still a patient in the hospital, but refuse return visits. One-time assessment visits may be made without charge to Medicare or the client, for skilled or supportive care, after which time, payment is required; and whether subsequent services are accepted may be evaluated more carefully. Other reasons to not follow through with additional visits may be that the client returns to the hospital, does not meet the criteria for coverage, or does not want the services (Personal communication, Karen Rizzo, April 20, 2004). We believed that if the client has agreed to more than one visit, the family has decided to use home care services.

Table 1.

Description of Measures

| Concept | Instrument | # | Scoring | Past and Current Psychometrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Event Trajectory | OARS (OMFAQ), “Physical Health” scale | 19 | Subjective health: Range 1–4; Objective health summed. Higher score = more acute trajectory | Test-retest reliability = .78 – .92 (Fillenbaum, 1988). Current Cronbach’s α = .59 (elders) and .68 (caregivers) |

| Functional Ability | OMFAQ, “ADL” scale | 15 | Range 0–30; higher score = more functional ability | Test-retest reliability = .88 – 1.0. (Fillenbaum). Current α = .89 and .90 |

| Service Awareness | Service Awareness Scale | 4 | Range 0 – 50; higher score = more Service Awareness | Current test-retest = .26 and .57 |

| Financial access | OMFAQ, Economic Resources scale | 15 | Subjective status: Range 1 –15; Objective status summed. Higher score = more financial access | Intra-rater reliability .67 – .91; (Fillenbaum). Current α = .75 and .76 |

| Impression Management | Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale | 24 | Range 0 – 24; higher score of socially desirable responses = more concerned with image | Cronbach’s α = .88; test-retest r = .89 (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). Current α = .56 and .72 |

| Caregiving Burden* | Caregiving Burden Scale |

15 |

Subjective burden: Range 0 – 45; Objective burden: see Functional Ability above. Higher score = more burden | Cronbach’s α = .67 – >.70 (Poulshock & Deimling, 1984). Current α = .95 |

| Acculturation | (ARSMA II) | 30 | Range 0 – 5; higher score = more acculturated to “Anglo culture” | Cronbach’s α = MA: 81; Anglo: .88; test-retest = MA: .72; Anglo = .80, 5 weeks later (Cuellar et al., 1995). Current α = .84 – .92 |

| Expectations of Familism | Familism Scale | 14 | Range 0 – 56; higher score = more influenced by familism norm | Cronbach's α = .64 – .72 (Sábogal et al., 1987). Current α = .79 and .80 |

| Perceived Experiences of Discrimination | Inventory of Life Experiences | 13 | Range 0 – 52; higher score = more perceived experiences of discrimination | Cronbach's α = .83 (Crist, 2004). Current α = .88 and .90 |

| Confidence in HCS | Community Service Attitude Inventory | 19 | Range 14 – 54; higher score = more confidence in HCS | 2 subscales supported by factor analysis in 2 studies; Cronbach’s α = .78 (Crist, Velazquez et al., 2006; Stommel et al, 1999). Current α = .61 – .80 |

| Use of HCS | OMFAQ, Services Assessment scale | 9 | No=0; “Yes” prompts the question “how many?”; 0–1=Non-Use; 2 or more of the same type of service=Yes | Satisfactory match found between community residents’ reports compared to local agencies’ reports of services use (Fillenbaum) |

| Cognitive status (screening tool; not a variable)* | Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) | 10 | Range 1–10. Higher score = increased cognitive ability (5 or less = moderate to severe dementia) | Test-retest r = .82–.83 (Pfeiffer, 1975) |

Key: * = Caregiving Burden was administered to caregivers only. The SPMSQ was administered to elders only.

Other measures were administered to both elders and caregivers. Except for being asked to assess elders’ health event trajectory and elders’ functional ability, elders and caregivers were instructed to report their own self-assessments on the rest of the measures.

Analysis

We had planned to use dyadic analysis to analyze elders’ and caregivers’ data sets. We first estimated the Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) coefficient between the elders’ and their caregivers’ scores on all variables that were hypothesized to affect use of HCS, to determine the extent of congruence in their responses. However, none of the ICC coefficients was greater than .80, which would indicate adequate dyad similarity to be explicitly considered in the analysis (Gonzalez & Griffin, 1999). Therefore, we examined elders’ and caregivers’ data separately for the two hypotheses. In addition to descriptive statistics, we tested the first hypothesis to evaluate whether contextual, social structural, personal, and attitudinal factors predicted the use of HCS, using forward stepwise logistic regression. We tested the second hypothesis, to evaluate the influence of cultural/ethnic factors on confidence in HCS, using stepwise multiple regression. We set alpha levels at the p = .05 level.

Findings

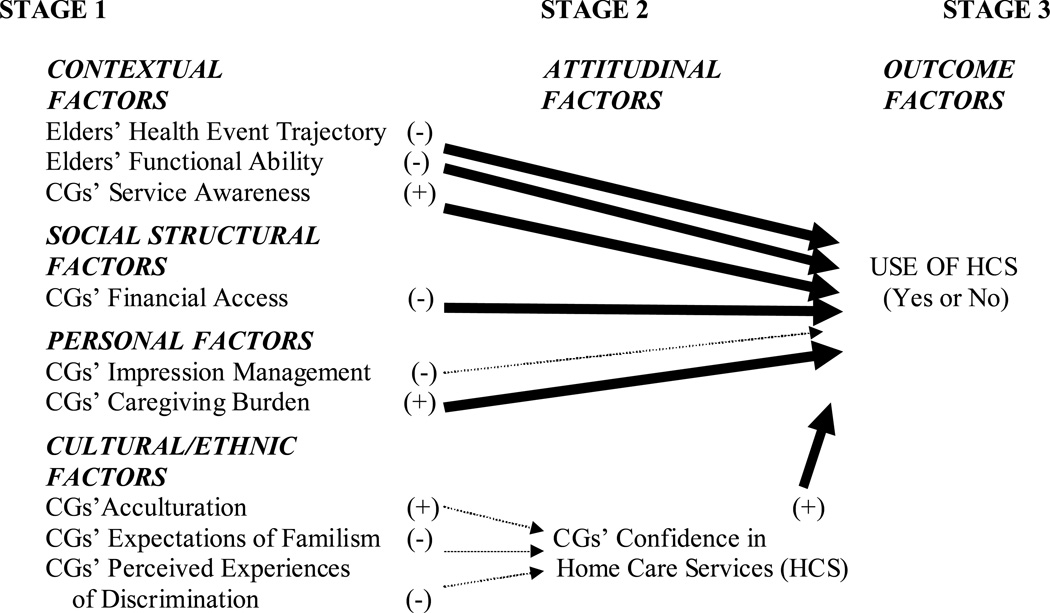

Testing of the logistic regression and multiple regression models showed that for elders, contextual, attitudinal, and cultural/ethnic factors were directly or indirectly related to their reports of their use of HCS (Figure 2). For caregivers, contextual, social structural, personal, and attitudinal factors were directly related to their reports of elders’ use of HCS (Figure 3). Elders reported that 31% of them had used HCS; caregivers reported that 32% of elders had used HCS. Of elders who used HCS, the most frequent diagnoses were gastrointestinal, renal, or orthopedic; and health insurance included Medicare, Medicaid, and elders’ or caregivers’ personal health insurance.

Figure 2. Mexican American Elders’ Use of Home Care Services Theory.

Results with direction of factors’ effect on use of HCS depicted with (+) or (−).

Key: CG= caregiver

Dark lines indicate significant results for elders.

Figure 3. Mexican American Family Caregivers’ Use of Home Care Services Theory.

Results with direction of factors’ effect on use of HCS depicted with (+) or (−).

Key: CG= caregiver

Dark lines indicate significant results for caregivers.

Elders’ Use of HCS Model

Of elders’ contextual factors, one subjective health event trajectory item and functional ability were significant predictors of HCS use. Elders who reported better health and performed ADLs and IADLS independently were less likely to use HCS. Of social structural and personal factors, no factor significantly predicted use of HCS. The attitudinal factor, confidence in HCS, significantly predicted use of HCS directly. Elders who had more confidence in HCS were likely to use HCS. For the second hypothesis, elders who reported higher expectations of familism (believed that only family should meet elders’ needs) were less likely to have confidence in HCS β = −.143).

Caregivers’ Use of HCS Model

Of caregivers’ contextual factors, one item of health event trajectory (number of medications), caregivers’ assessment of elders’ functional ability, and caregivers’ own service awareness significantly predicted use of HCS. Caregivers’ reports indicated that when their elders took more medication and when caregivers were more aware of HCS, elders were 1.17 times more likely to use HCS. Caregivers’ reports indicated that if their elders performed ADLs and IADLS independently, elders were less likely to use HCS. Social structural (subjective financial resources) and personal (objective caregiving burden) factors significantly predicted use of HCS. Caregivers who rated their income as high were likely to report elders used HCS. Caregivers who reported burden related to higher elders’ objective impairment were 1.21 times more likely to report elders used HCS. Caregivers’ attitudinal factor, confidence in HCS, significantly predicted use of HCS. Caregivers who had more confidence in HCS were 1.10 times more likely to use HCS. With regard to the second hypothesis, none of the cultural/ethnic factors predicted caregivers’ confidence in HCS.

Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with the literature that reports lack of congruence between elders’ and caregivers’ responses to contextual factors such as elders’ condition and ability. For example, caregivers often report more impairment than elders (Lyons, Zarit, Sayer, & Whitlatch, 2002).

The significant contextual factors (health event trajectory, functional ability) reported by elders and caregivers in Hypothesis 1 are congruent with previous research (Alkema, Reyes, & Wilber, 2006). Also, caregivers’ significant social/structural factor (financial access) is congruent with previous research (Chiriboga, Black, Aranda, & Markides, 2002).

We view two of three of the contextual and the social structural factors as “givens” and not amenable to change. Caregivers’ service awareness, however, was the one significant contextual factor that may be highly amenable to change and should be targeted when interventions are designed to increase use of HCS. Interventions should be designed to address all three dimensions of elders’ Service Awareness: knowing that these services exist, recognition that HCS are needed, and potential to access HCS. Such an intervention could also address elders’ and caregivers’ confidence in HCS. An earlier study that found that the process of deciding to use HCS was initiated by the caregiver in MA families (Crist, García-Smith, & Phillips, 2006). The fact that caregivers’ but not elders’ responses about Service Awareness were significant demonstrates that elders may need more understanding about HCS, and that caregivers’ awareness about service currently is the key to the use of HCS.

Future interventions should attempt to diminish the one significant personal factor, caregiving burden. Burden has been shown to have negative physical and psychological outcomes for the family caregiver, for example, cellular immune responses, weight change, problems with health and medical conditions, depression, and negative affect (Phillips, Brewer, & Torres de Ardon, 2001). Burden is a complex construct and is associated with multiple factors, even in non-Hispanic white caregivers (Halm, Treat-Jacobson, Lindquist, & Savik, 2006). MA family caregivers have claimed that they would welcome the use of HCS because they were often not able to provide the care expected by their elders as efficiently or effectively as needed (Crist, 2002). Caregiving burden was only significant for the “objective” dimension, essentially elders’ lack of functional ability, but not the subjective perception of burden. We must recognize, as Alemán (2000) noted, that MA family members provide care for each other with motivations distinct from Anglo families’ “social exchange” paradigm. The expression “Que Dios te lo pague” (“God will reward you for it”) represents the cultural norm that family members’ good deeds are appreciated, blessed, and rewarded by God rather than by dependent members’ being reciprocally indebted to their caregivers (Alemán, p. 14). Research should continue to examine the absence of significant findings for subjective burden, to determine whether caregivers’ responses reflect actual perceptions that family care is part of life, so that it is not recognized, or whether cultural norms preclude them from reporting perceived burden. Interventions should then be tested regarding effect on caregiving burden.

For Hypothesis 2, the more strongly elders reported they embraced the cultural tenets of familism, the more likely they were to report lower levels of Confidence in HCS, which in tern reduced elders’ use of HCS. The cultural/ethnic factor, expectations of familism, promotes the internalized norm in elders and their family caregivers that family members should be able to provide all care that is needed, and the beliefs that family caregivers can give better care than outsiders, and that elders are safer being cared for by family caregivers (Sábogal et al., 1987). Based on this Mexican tradition, MA elders have a sense of mistrust and fear, if care is provided by someone who is not a member of the family. “Mistrust of service delivery institutions” (Calderón-Rosado et al., 2002, p. 4) result in reluctance to use community services (Crist, Velazquez et al., 2006). Future interventions will need to be designed to include the whole family, demonstrating to elders that HCS’ providers’ approaches will enhance, supplement, and support the family, rather than replace the caregiver’s essential role.

Limitations

This was the first time the Service Awareness Scale and revised Confidence in Home Care Services questionnaire were used in a large study (Crist, Michaels et al., 2007; Crist, Velazquez et al., 2006). The low test-retest scores of the Service Awareness Scale may have been due to increased learning about services during the data collection process. We will continue to test and refine the instruments to improve the low Cronbach’s alpha for the Fear and Worry subscale of the Confidence in Home Care Services questionnaire. We will continue to evaluate other instruments that also did not show significance with our sample (the Crowne and Marlowe’s Social Desirability Scale [1960]; the new Inventory of Life Experiences, measuring perceived experiences of discrimination [Crist, 2004]; and Subjective Health [Fillenbaum, 1985]) and how adequately these measures perform in studies with MA participants, whether modifications of the measures can be made, or whether we need to select other measures for future studies with this population to more accurately test for significance. Our method of representing the dependent variable, use of HCS, admittedly does not recognize that some benefits could occur with one-time visits. In future studies we will consider ways to measure the outcome score that could potentially provide more variability in the results.

It is possible that differences in the two models may be reflected by acculturation. Caregivers may have may have been more likely to have been born and education in the U. S., bilingual, and more likely to respond more similarly to Anglo responses. Caregivers generally reported higher levels of acculturation compared to elders’ levels, which may have affected responses regarding personal, cultural/ethnic, and attitudinal factors. Based on these differences, different interventions will need to be designed for elders and caregivers. For example, we may need to design interventions for caregivers, such as increasing Service Awareness, which would require more experiences and ability in understanding and negotiating within the current non- Hispanic-white dominant U. S. culture. In contrast, interventions for elders may need to be delivered by people who more closely represent the elders’ group, for example, promotoras with whom elders may more easily identify. Additionally, issues that should be addressed in future research include the ethnicity of home care nurses and other staff, and how rural vs. non-rural residence may affect use of HCS.

Conclusion

In the context of ever-increasing personal and governmental healthcare costs, use of HCS can decrease total healthcare expenditures. Post-hospital care involves billions of dollars of the federal budget. HCS can decrease the burden to society by decreasing the costs of institutionalization, which is starting to increase in the MA community (Murtaugh & Litke, 2002). Home care has the potential to help avoid transition problems such as inappropriate use of emergency departments, unnecessary hospitalizations, and returns to nursing homes after discharge into the community. Interventions targeted toward increased service awareness and confidence in HCS may reduce health care disparities, improving elder and caregiver outcomes while decreasing both personal and national costs.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression and Multiple Regression Results for Significant Factors that Influence Use of Home Care Services (n = 140)

| Elders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | ||||||

| Significant variables | Coefficient | Standard Error |

Wald | Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

|

| Contextual Factors: | ||||||

| Subjective Health | −.271 | .139 | 3.819 | .763 | .581 | 1.001 |

| Functional Ability | −.004 | .001 | 15.723 | .996 | .994 | .998 |

| Attitudinal Factor: | ||||||

| Confidence in HCS | .089 | .035 | 6.522 | 1.093 | 1.021 | 1.170 |

| Hypothesis 2 | ||||||

| Significant variables | Coefficient | Standard Error |

R2 | t | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

| Cultural/Ethnic Factors: | ||||||

| Expectation of Familism | −.143 | .067 | .032 | −2.149 | −.275 | −.011 |

| Caregivers | ||||||

| Hypothesis 1 | ||||||

| Contextual Factors: | ||||||

| Objective Health | .193 | .077 | 6.248 | 1.213 | 1.043 | 1.412 |

| Functional Ability | −.004 | .001 | 13.210 | .996 | .994 | .998 |

| Service Awareness | .152 | .068 | 4.990 | 1.165 | 1.019 | 1.331 |

| Social Structural Factor: | ||||||

| Subjective Financial Resource | −.274 | .144 | 3.638 | .760 | .574 | 1.008 |

| Personal Factors: | ||||||

| Objective caregiver’s burden | .191 | .080 | 5.768 | 1.211 | 1.036 | 1.416 |

| Attitudinal Factor: | ||||||

| Confidence in HCS | .095 | .035 | 7.220 | 1.099 | 1.026 | 1.178 |

| Hypothesis 2 | ||||||

| Significant variables | Coefficient | Standard Error |

R2 | t | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

| No significant variables | ||||||

Significant at p< .05

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) supported this research through grant # 1 R15 NR009031-01. We thank Dr. Linda Phillips, PhD, RN, Professor and Audrienne H. Moseley Endowed Chair in Nursing, College of Nursing, University of California at Los Angeles; Dr. Darlene Mood, PhD, Professor Emeritus, Wayne State University; Dr. Donald Gelfand, PhD, Professor Emeritus, Wayne State University, Affiliate, Arizona State University, and Research Associate, Center on Aging, The University of Arizona; and Dr. Souraya Sidani, PhD, RN, Professor, University of Toronto, for their consultation on the design and analysis; the Office of Nursing Research Writers’ Group for editorial consultation; and research assistants and specialists and the ENCASA Community Advisory Council are acknowledged for their language and cultural skills to form an effective community partnership.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Janice D. Crist, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona, PO Box 210203, Tucson, AZ 85721-0203, 520-626-8768, jcrist@nursing.arizona.edu.

Suk-Sun Kim, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

Alice Pasvogel, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

Humberto Velazquez, University of Sinoloa, Sinoloa, México.

References

- Alemán S. Mexican American elders. In: Alemán S, Fitzpatrick T, Tran TV, Gonzalez E, editors. Therapeutic interventions with ethnic elders: Health and social issues. New York: Haworth; 2000. pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Alkema GE, Reyes JY, Wilber KH. Characteristics associated with home- and community-based service utilization for Medicare managed care consumers. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(2):173–182. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G, Horvath J. Chronic conditions: Making the case for ongoing care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Rosado V, Morrill A, Chang B, Tennstedt S. Service utilization among disabled Puerto Rican elders and their caregivers: Does acculturation play a role? Journal of Aging and Health. 2002;14(1):3–23. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Home health agency utilization and expenditure data by race and age group calendar year 2001. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services unpublished data. The data were extracted from the Health Care Information System. 2003 Available: Medicarestats@cms.hhs.gov.

- Chiriboga DA, Black SA, Aranda M, Markides K. Stress and depressive symptoms among Mexican American elders. Journal of Gerontology: PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES. 2002;57B:P559–P568. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui L, Sands LP, Sehgal AR, Walter LC, Wieland D, Eleazer GP, Yaffe K. Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2001;56:M707–M713. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD. Support for families at home: Mexican American elders’ use of skilled home care nursing services. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19:366–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD. Paper: The Inventory of Life Experiences: Measuring Mexican American elders’ perceived experiences of discrimination. The Gerontologist, Program Abstracts, 57th Annual Scientific Meeting. 2004;44(1):284. [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, García-Smith D, Phillips LR. Accommodating the stranger en casa: Mexican American elders’ decisions to use home care services. Research and Theory in Nursing Practice. 2006;20(2):109–125. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.20.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Michaels C, Gelfand DE, Phillips LR. Developing an understanding and measurement of service awareness among elders and caregivers of Mexican descent. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2007;21(2):48–64. doi: 10.1891/088971807780852002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Velazquez JH, Ramirez Figueroa D, Durnan I. Instrument development in cross-cultural research with elders and caregivers of Mexican descent. Public Health Nursing. 2006;23(3):284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:249–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Griffin D. The correlational analysis of dyad-level data in the distinguishable case. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Halm MA, Treat-Jacobson D, Lindquist R, Savik K. Correlates of caregiver burden after coronary artery bypass surgery. Nursing Research. 2006;55(6):426–436. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200611000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, Whitlatch CJ. Caregiving as a dyadic process: Perspectives from caregiver and receiver. Journal of Gerontology: PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES. 2002;57B(3):P195–P204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan EA, Tullai-McGuinness S, Neff DF. Home health services research. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2002;20:267–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magilvy EA, Congdon JG. The crisis nature of health care transitions for rural older adults. Public Health Nursing. 2000;17:336–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG, Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Andreski P. Feeling better: Trends in general health status. Journal of Gerontology, SOCIAL SCIENCES. 2007;62B(1):S11–S21. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Verdon J, Tousignant P, de Courval LP, Dendukuri N, Blzile E. Rapid emergency department intervention for older people reduces risk of functional decline: Results of a multicenter randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:1272–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh CM, Litke A. Transitions through postacute and long-term care settings: Patterns of use and outcomes for a national cohort of elders. Medical Care. 2002;40:227–236. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1975;23:433–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, Brewer BB, Torres de Ardon E. The Elder Image Scale: a method for indexing history and emotion in family caregiving. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2001;9(1):23–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: Assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. HSR: Health Services Research. 1998;33:571–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulshock SW, Deimling GT. Families caring for elders in residence: Issues in the measurement of burden. Journal of Gerontology. 1984;39(2):230–239. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sábogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sábogal R. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Stommel M, Collins C, Given B, Given CW. Correlates of community service attitudes among family caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1999;18(2):145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Torres C. Elderly Latinos along the Texas-Mexico border: A healthcare challenge for the 21st century. Journal of Border Health. 2001;1(2):28–36. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census. Immigrant elders: Living arrangements, 1850–2000. [Accessed February 17, 2007];2002 from http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056.html.

- Wallace SP, Levy-Storms L, Kington RS, Andersen RM. The persistence of race and ethnicity in the use of long-term care. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B(2):S104–S112. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.2.s104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]